Abstract

The purpose of this review is to highlight some of the issues that need to be addressed in order to optimally utilize functional neuroimaging as a clinical tool to predict outcomes in substance use disorders. First, the importance of recognizing the clinical heterogeneity of substance use disorders population is highlighted. We also emphasize that empirical and theoretical analyses support the idea that the courses of substance use disorders are relatively independent of the types of substance being used. Second, various approaches to the measurement and characterization of the longitudinal courses of substance use disorders are summarized. Third, predictors of outcomes are reviewed and their limitations are discussed. Within this context, we describe aspects of our work that focus on using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to predict outcomes. Fourth, we discuss future directions, critical experiments and the utility of functional neuroimaging as a clinical tool.

Keywords: Addiction, Stimulants, Outcomes, Prediction, fMRI, Neuroimaging

Substance abuse and dependence have an enormous impact on society. For example, in the United States, the lifetime prevalence of substance abuse or dependence in adults is over 15% 1. The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health estimate the cost to be $246 billion in 1992, the most recent year for which sufficient data were available 2. In 2006, an estimated 20.4 million Americans aged 12 or older used illicit drug over the past month, which represents 8.3% of the population aged 12 years or older 1. According to a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) report, 14.8 million individuals used marijuana in the past month, and illicit drugs other than marijuana were used by 9.6 million persons. Rates of substance abuse and dependence are generally greater among men, Native Americans, individuals age 18 to 44 years, those of lower socioeconomic status, those residing in the western part of the United States, and those who were never married or are widowed, separated, or divorced 3,4.

There is significant comorbidity between substance dependence with most mood disorders and anxiety disorders 4,5. Interestingly, only a minority of individuals with substance use disorders seek treatment 4. Psychiatric comorbidity has a profound influence on course and outcome. Individuals with substance use disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder, relative to those with substance use disorders only, are more impaired, have greater psychosocial problems, and show a more severe course 6. Similarly, comorbid antisocial personality disorder 7 results in earlier onset of substance use disorders, greater multi-substance use 8, poorer outcomes, more severe course, and other psychosocial dysfunctions 9,10.

A central characteristic of addictive behaviors is their chronically relapsing nature 11. Relapse is a complex process and includes multiple dimensions such as the process prior to re-use of the drug, the event of using the drug, the level to which the use returns, and the consequences associated with use 12. Several models that stress cognitive behavioral 13, person-situation interactional 14, cognitive appraisal 15, and outcome expectation factors 16,17 have been put forth to explain the process of relapse. These models differ in the extent to which the focus is on the person (decreased self-efficacy), the situation (exposure to high-risk environments), and/or their interaction (insufficient mobilization of coping skills) 18. On the other hand, psychobiological models of relapse have been based on opponent process and acquired motivation theories 19, craving or loss of control 20, urges or craving 21, withdrawal 22, and kindling processes 23. These models focus on the fact that brain reward systems become sensitized to drugs and drug-associated stimuli 24 resulting in increased “drug-wanting”, which increase the susceptibility to relapse. Some investigators have suggested that relapse is best understood as having multiple and interactive determinants that vary in their temporal proximity from and their relative influence on relapse. Therefore, an adequate assessment and prediction model must be sufficiently comprehensive to include theoretically relevant variables from each of the multiple domains and different levels of potential predictors 12. Others have pointed out that relapse is not a binary but a continuous outcome across multiple dimensions 25, which include the threshold, duration, prior sobriety level, number of substances involved, and consequences. Moreover, relapse encompasses a multidimensional response pattern with (1) the occurrence of negative life events; (2) cognitive appraisal variables including self-efficacy, expectancies, and motivation for change; (3) subject coping resources; (4) craving 27,28 experiences; and (5) affective/mood status 11.

Some investigators have suggested that aberrant learning processes within subcortical circuitry underlie aspects of observations that 1) drug-seeking behavior becomes compulsive and habitual; 2) propensity for relapse to drug-seeking can be manifest even after long periods of sobriety 26. Others have suggested that substance use disorders are consequences of imbalances between overactive “impulsive”-amygdala systems, which signal pain or pleasure of immediate prospect, and weakened “reflective” prefrontal cortex system for signaling pain or pleasure of future prospect 27. In particular, drugs and/or conditioned stimuli associated with the availability of drug are thought to overwhelm the goal-driven cognitive resources important for exercising the willpower to resist drugs 27. Finally, some have argued that substance dependence is characterized by an overvaluing of drug reinforcers associated with an undervaluing of alternative reinforcers in combination with deficits in inhibitory control 28. Based on animal experiments, Koob and LeMoal have conceptualized substance dependence or addiction as a cycle of increasing dysregulation of brain reward systems, which leads to compulsive drug use and a loss of control over drug-taking. Both, sensitization and counter-adaptation processes contribute to this hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. The neurobiological mechanisms involved include the mesolimbic dopamine system, opioid peptidergic systems, and brain and hormonal stress systems 29. Based on these views, it is clear that brain processes that are candidates for monitoring clinical states involve learning, drug and conditioned cue-related processing, homeostatic regulation, inhibition, and decision-making.

Predictors of Outcome

A number of different domains have been tested for their ability to predict relapse. Here we segregate the results into four different factors: sociodemographic, clinical, psychological, and cognitive variables. The implications of these data for practical use in predicting clinical outcomes in addiction are limited, however, due to a number of factors. First, samples may be small, non-representative, focused on subgroups of treatment seeking individuals, and only take a few substances into account. Second, outcome variables are varied and may consist of treatment adherence, relapse, or drop out from an ongoing program. Third, psychiatric comorbidity and diagnostic status is often not carefully defined. Nevertheless, the results from these studies focus our attention on possible candidate processes for functional neuroimaging studies.

Socio-demographic Factors

Employment status, history of injecting the drug of abuse, sexual promiscuity during the six months prior to admission predict higher rates of relapse in cocaine dependent subjects 30. Although patterns of use differ between males and females, predictors of relapse, i.e. residential instability, multiple drug use, single marital status, unemployment, an older age, and treatment dropout differ less between genders 31. Some investigators have observed that being around other users accounted for nearly half of relapse events. Family or work stress was associated with relapse in a third of the cases, and unpleasant affect in about a quarter of cases 32. Some investigators have found higher relapse rates in subjects who had experienced significant negative life events in a three month period prior to relapse 33, although others did not find significant associations between life events and relapse 11. Higher severities of patient problems at the outset of treatment and shorter stays in treatment predicted higher relapse rates in cocaine dependent subjects 34,35. Findings by other groups also showed that shorter length of treatment, older age of first substance use, involvement in selling methamphetamine, and more previous time in treatment 36 predicted poorer treatment responses. Women in treatment who had multiple co-occurring addictions and depression showed higher rates for relapse 37. These results show that socio-demographic factor, circumstances, and possibly gender may have an influence on the course of addiction.

Clinical Factors

Shorter delay between the onset of a mental health disorder and the beginning of outpatient mental health care has been associated with lower mortality and better substance use outcome 38. Unfortunately, substance abuse treatment success rates, often little more than 1/3rd of dependent individuals, are significantly lower than the 50–60% success rates typical of treatment of other psychiatric disorders 39. Short term abstinence at 6 months, which is predicted by older age, being female, attending a 12 step program, and associating with recovery oriented social networks, is an important predictor of long-term abstinence at 5 years 40. Clinical comorbidities such as polydrug abuse, psychiatric conditions and previous head injury may be associated with increases in impulsive decision-making and subsequent greater risk to relapse 41. Similarly, increased psychiatric severity was a significant and poor predictor of substance use outcomes 42. However, others have noted that levels of anxiety symptoms at the beginning of treatment are not predictive of outcomes in cocaine users 43. In opiate dependent individuals, high level of pretreatment opiate/drug use, prior treatment for opiate addiction, no prior abstinence from opiates, abstinence from/light use of alcohol, depression, high stress, unemployment/employment problems, association with substance abusing peers, short length of treatment, and leaving treatment prior to completion were found to be predict longitudinal course 44. Subjects with more severe consequences of drug use and less social exposure to drug use during treatment were found to show lower relapse rates during treatment 45. Taken together, outcomes are influenced by multiple clinical factors although each factor by itself accounts for only a small portion of the variance.

Psychological Factors

Craving is an important psychological phenomenon that has been closely linked to relapse 46,47. In alcohol using subjects, results of structured interviews that assess frequency and intensity of craving were able to correctly predict 75% of the subjects who relapsed to alcohol use 11. Similarly, craving intensity significantly predicted methamphetamine use in the week following each craving report. Craving remained a highly significant predictor in multivariate models that control for pharmacological intervention and for methamphetamine use during the prior week. Craving scores that preceded use were 2–3 times higher than scores that preceded abstinence. Similarly, risk of subsequent use was 2–3 times greater for scores in the upper half of the scale relative to scores in the lower half 48. Whereas 90% of subjects who reported no cravings for cocaine after treatment remained totally abstinent after 3 months, only a third of those who reported still having cravings after treatment were abstinent during this time 32.

Others have noted that antecedent experiences to relapse were almost exclusively negative emotional states (e.g. depression and loneliness) 49. Preclinical research has shown that stress, in addition to drugs themselves, plays a key role in perpetuating drug abuse and relapse. However, many of the details concerning the mechanisms underlying this association in humans remain unclear. A greater understanding of how stress may perpetuate drug abuse will likely have a significant impact on both prevention and treatment development in the field of addiction 50. Interestingly, the degree of distress and satisfaction when entering treatment are not related reliably to dropout or relapse 51. Coping skills and use of coping strategies have also been related to relapse. Coping, as measured by a series of scales, which included social support, religious and community involvement, work, and recreational activities was able to correctly predict 85% of subjects relapsing to alcohol use 11. Moreover, coping factors reflecting problem-focused, social-support, self-blame, and wishful-thinking strategies successfully predicted 6-month outcome status in alcohol-dependent adolescents 52. In comparison, self-efficacy (defined as confidence in being able to resist the urge to drink heavily) assessed at intake of treatment, was strongly associated with the level of consumption on drinking occasions at follow-up 53. Lower self-efficacy scores at intake predicted subsequent heavier drinking. Therefore, stress, coping, and the ability to modulate emotions are important processes to consider for predicting outcomes.

Several personality variables have been associated with differential levels of relapse. For example, higher levels of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion were associated with greater confidence in ability to refrain from use, whereas neuroticism was associated with a corresponding lack of confidence in self-restraint 54. High levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness predicted higher relapse rates 55. Orderliness and Persistence factors on the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire predicted longer latencies to relapse in alcohol dependent subjects 56. Some investigators have related the diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder to the likelihood of relapse 56, whereas others did not show an association 34. Accumulating evidence indicates that the detached, dependent, and antisocial personality aspects increase propensity to relapse 33. Higher scores on the MMPI-2 Psychopathic Deviate scale predicted relapse in a Cox proportional hazard model among abstinent alcohol dependent subjects 57. Among the different impulsivity dimensions, urgency (i.e. a tendency to act impulsively in response to negative emotional states) has been shown to be a good predictor of severity of medical, employment, alcohol, drug, family/social, legal and psychiatric problems in substance dependent individuals. This factor explains13–48% of the total variance 58. In summary, similar to clinical factors, psychological factors clearly influence outcome, however, there is not a single outstanding predictor of long-term outcome.

Cognitive and Physiological Factors

Neuropsychological studies of substance abuse treatment outcome have found that individuals who recover successfully show intact functioning on most measures, whereas those who relapse do poorly on tests of language, abstract reasoning, planning, and cognitive flexibility 59. For example, approximately 74% of subjects who recalled less than or equal to half the items of the Product Recall Test relapsed at 3 months compared to only 33% of the subjects who recalled more than half the items 60. Consistent with the important role of level of executive function as a risk for relapse is the finding that attention/executive functioning scores obtained at the intake neuropsychological assessment significantly predicted substance use and dependence symptoms 8 years later, even after controlling for intake substance involvement, gender, education, conduct disorder, family history of substance use disorders, and learning disabilities 61. Similarly, significant increases in attentional distraction for alcohol stimuli during the 4 weeks of inpatient treatment was observed in alcohol using subjects who relapsed or did not maintain post-discharge outpatient contact 62. Finally, higher verbal skills, as measured by the Shipley Institute of Living Scale predicted correctly 64% of subjects who did not relapse to using drugs or alcohol 63. A discriminant function analysis using the P300 amplitude in an event-related potential study during a selective visual attention task was able to identify 70% of subjects with cocaine dependence who later relapsed, and 53% of the subjects who did not 64. Polysomnographic sleep latency has also been found to be the most significant predictor of relapse in alcohol-dependent subjects 65.

Decision-making has been proposed to represent an essential ingredient for understanding relapse 66. Performance on two tests of decision-making, but not on tests of planning, motor inhibition, reflection impulsivity or delay discounting, was found to predict abstinence from illicit drugs at 3 months with high specificity and moderate sensitivity. In particular, two thirds of the participants who performed normally on the Cambridge Gamble Task and the Iowa Gambling Task, but none of those impaired on both, were abstinent from illicit drugs at follow up 67. Others have found that longer duration of the disorder, neurocognitive indicators of disinhibition and decision-making but not self-reported impulsivity or reward sensitivity were significant predictors of relapse 68. Although substance use disorder individuals have significant deficits in the recognition of facial emotional expressions, these performance deficits were not related to length of abstinence, providing evidence for behavioral specificity 69. Thus, decision-making paradigms are good behavioral candidates to predict clinical outcomes. Refining these paradigms to better probe specific aspects of this complex process 70 may enhance their prediction accuracy in the future.

In conclusion, relapse is a complex and multi-dimensional process. It is thus not surprising that multiple assessment domains can be related to relapse susceptibility. Surprisingly little research has been conducted to relate neurobiological variables to relapse susceptibility. Some of the cognitive variables that are known to correlate with increased risks for relapse, e.g. executive functioning, can be readily assessed using functional brain imaging. Thus, in addition to cognitive, psychophysiological, socio-demographic, social and psychological tests, measuring brain functioning during cognitively or emotionally challenging tasks may provide an important predictor for treatment outcome greater insights into the nature of the cognitive and affective dysfunctions in substance dependent subjects.

Using fMRI to predict relapse

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a tool to map cognitive, affective, and experiential processes onto the brain regions that subserve them, and is increasingly a method of choice to identify individual differences in many of these processes. Although the human brain comprises only about 2% of the body mass, it accounts for approximately 20% of its total oxygen consumption 71. Deoxyhemoglobin has paramagnetic effects in the blood upon the nuclear magnetic resonance transverse relaxation times of water protons that reside nearby in the tissue 72. Blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is based on the fact that changes in the blood oxygen levels affect the fraction of hemoglobin in the deoxygenated state and thus provide an MRI contrast agent 73. BOLD fMRI experiments in the awake human visual cortex show that the ratio between BOLD-fMRI signal change and baseline signal is linearly proportional to the change in blood flow relative to the baseline blood flow 74. Moreover, increases in baseline blood flow are thought to be proportional to total deoxyhemoglobin within any volume element (voxel) 75. For example, increasing cerebral blood flow using CO2 administration reduces the BOLD response to the same task substantially 76. Therefore, the BOLD signal reflects the effect of neural activity on dynamic changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume, and the cerebral rate of oxygen metabolism through a process generally referred to as neurovascular coupling. An often under-appreciated aspect of BOLD-fMRI is that the interpretation of the results critically depends on the details of the task conducted during the imaging procedure. Whenever a neural substrate is being described as “activated” in a study or whenever two populations are described as differing in their activation patterns, one has to keep in mind that these differences are described in the context of the task conducted. Further, fMRI measurements are of relative character, meaning that brain function during a task of interest, e.g. decision-making, has to be related to a certain experimental baseline. The baseline itself can vary and studies either use so-called low level baselines, for instance displaying a blank screen or fixation cross, or high level baselines, where an event with similar physical, but different cognitive characteristics will be drawn on for statistical comparison. The nature of the reference baseline itself therefore influences the results. Taken together, fMRI is a proxy measure for how complex cognitive, emotional, social and other experiential processes are implemented in different neural systems, rather than simply about increases or decreases in activation of certain brain regions.

In a longitudinal study of methamphetamine dependent individuals we used a two-choice prediction task to probe simple decision-related processing. By comparing brain activation during a two-choice response task relative to a two-choice prediction condition, we were able to separate sensorimotor processing from prediction and decision-making. Individuals who engage in this task show bilateral activation of prefrontal cortex, striatum, posterior parietal cortex, and anterior insula during decision-making 77. Individuals who relapsed, but not those who did not, showed attenuated or reversed activation patterns in prefrontal, parietal, and insular cortical regions. Optimized prediction calculations based on step-wise discriminant function analyses revealed that right insula, right posterior cingulate, and right middle temporal gyrus response best differentiated between relapsing and non-relapsing methamphetamine dependent subjects. In combination, we obtained 94% sensitivity, with 86% specificity using this approach. Using Cox Regression analyses, we were able to predict time to relapse. This study demonstrated that the attenuated activation patterns during decision-making may play a critical role in processes that “set the stage” for relapse 12. Kosten and colleagues 78 presented videotapes showing cocaine smoking to recently abstinent cocaine dependent subjects while acquiring BOLD fMRI and assessing craving. Activities in sensory, posterior cingulate and superior temporal cortical as well as lingual and occipital gyri showed significant correlations with treatment effectiveness. Subsequent relapsers and abstinent patients differed in their activation in the right temporal and precentral, left occipital and posterior cingulate cortical regions. Such recent developments in fMRI study designs and analyses show that fMRI may become a useful tool to identify people at high risk for relapse to substance abuse, at stages where both, patients and therapists may have few other means for identifying such increased susceptibility to relapse. Preliminary results specifically highlight roles for the medial prefrontal cortex, the sensory cortex, the anterior and posterior cingulate gyri, the insula and the right middle temporal gyrus in relapse processes.

Methodological considerations

Although functional brain imaging has become a powerful tool to investigate the physiological basis of psychiatric or neurological disorders, it has only very recently been used to predict clinical outcomes in individual patients. Since MRI instruments are widely available, the use of this technology for identifying subjects at high risk and for predicting individual differences in treatment responses and relapses is particularly appealing. Such studies could provide insights into other psychiatric and neurological disorders in ways that have implications for the underlying assumptions and methodologies of fMRI.

Two major types of functional imaging studies are typically used: studies with only one or those with two imaging sessions. Extending the initial use of fMRI to characterize the neural correlates of major psychiatric symptoms, researchers have begun to develop study designs that incorporate fMRI into the diagnostic and treatment process. Several cross-sectional studies using single functional brain scans have aimed at differentiating activations of healthy subjects, patients and individuals who are at high risk (e.g. on genetic or other bases) for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia 79,80. In subsequent work, studies combined initial brain scans with psychopathological and neuropsychological re-assessments in abstinent stimulant 81 and cocaine 78,82 users, and a small sample of abstinent alcoholics 83. These authors were able to differentiate brain activation patterns of patients with subsequent drug use from those of abstinent patients.

The practical relevance of post-treatment brain scans for translational medicine seems to be limited, since decisions about treatment selection and other clinical decisions often have to be made prior to second, post-treatment imaging sessions. Nevertheless, functional imaging studies with two imaging sessions were among those used to monitor and predict the effect of specific treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy in depression 84 or schizophrenia 85 or of recovery after stroke 86.

Statistical Approaches

Several statistical approaches can be applied to predict future outcomes. Functional brain images are extraordinarily rich data sets. They provide data concerning the time courses of activations of thousands of brain voxels. Type I errors have to be monitored adequately. For these reasons, hypothesis-driven region of interest (ROI) approaches are now more frequently being used to limit the number of statistical comparisons. Simulation methods such as the Monte Carlo simulations are applied to set statistical thresholds. Neighboring voxels may or may not belong to the same cell assembly; spatial smoothing as applied in most imaging analyses routines adds to activation overlays at some cost of power to identify small regions of interest. Predictions based on patterns of neural activation thus have to face unique demands that need to be addressed by both statisticians and neuroscientists.

The very limited number of published papers that seek to use fMRI data to predict clinical outcomes adopt diverse analysis approaches. A set of baseline predictive variables has to be chosen and relevant (non-)imaging variables selected as the brain activation paradigm is chosen. Multivariate linear regression models using forward 86 or stepwise 87 regressions can determine the change in activation. However, if the number of baseline predictors is large, as it will be true if whole brain analyses are preformed, multiple regressions can be inappropriate. Multivariate approaches that include principal component analyses and/or partial least squares analyses (PLS) should then be considered. PLS analyses for fMRI data hold the advantage of assuming that cognitive tasks are processed in networks of voxels 88. Guo and colleagues 89 recently introduced a Bayesian hierarchical model for PET and fMRI data to forecast brain activity in schizophrenic patients following a specific treatment. In addition to the specific statistical model to be applied, future research will also have to identify which characteristics of brain activation will be relevant for clinical predictions. Candidate parameters include: the strength of the BOLD signal, the size of activated clusters, and the delay or shape of the hemodynamic responses.

Ethical implications

As results from structural and functional imaging gain more and relevance for predictions or responses in individual psychiatric and neurological patients, researchers will need to better anticipate and evaluate implied ethical concerns. The medical and social consequences of predicting drug dependency or relapse, based on functional brain images, have to be acknowledged. Effects on health insurance and stigmatization are obvious issues. Measures to guarantee confidentiality will have to be identified. Individuals at high risk for relapse may be liable to increased stress of such testing and predictions, which themselves may increase relapse risks.

Outcome – beyond relapse

In simple terms, substance use disorders have been described as being “absent” or “present”. “Relapse” has been identified with the recurrence of the condition. However, “relapse” represents a somewhat arbitrary binary judgment imposed on a complex clinical condition. Moreover, the use of the term “relapse” has been criticized because it connotes an unrealistic and inaccurate conception of how successful change can occur over time 25. Thus, substance use disorders are not sufficiently quantified by presence or absence of abuse or dependence 90. Some investigators have argued that the expression of substance use disorders should be based on a general liability model across drug classes, which results in a quantitative rather than discrete expression of a disorder phenotype 91. The temporal expression of the substance use disorder phenotype of an individual can thus be viewed as the momentary probability that an individual will express a certain degree of substance use and associated problems. The Addiction Severity Index 92, has been suggested as a reliable and valid instrument to quantify the severity of substance use disorders. Similarly Timeline Follow-Back Latent trajectory class analysis 93 is a useful method for aggregating individuals who have similar symptom patterns over time into course of illness groups 94. This statistical approach may have a quantitative advantage over rules-based assignment based on a priori criteria because it attempts to maximize the extraction of information from empirical data rather than following a specific operational convention of rules. Recently, latent trajectory class approaches have been utilized to examine substance use trajectories 95. These approaches reveal substantial commonality for disorders associated with a variety of substance types 96. Most follow similar longitudinal courses irrespective of the particular drug used. Others have argued that a number of factors such as age, type of substance, problem severity, and chronicity, influence the longitudinal expression of substance use disorders 97. Specifically, six trajectory classes have been identified in men with substance use disorders 97. Among these classes were those with early-onset and severe substance use disorder symptoms persisting into adulthood, individuals with early-onset who improve over time, and other groups with symptoms that emerge later and with varying degrees of severity and persistence 97. Others have found associations between the longitudinal courses of substance use disorders and psychiatric comorbidity, marital and employment status 94. Using similar approaches in individuals with alcohol or tobacco use disorders, five different trajectory types were found, which were associated with densities of family history or substance abuse, gender, alcohol expectancy, behavioral undercontrol, and childhood stressors 98. In summary, the longitudinal expression of substance use disorder is complex, non-uniform, and may not be adequately quantified by a binary state of relapse. Therefore, predicting outcomes using functional neuroimaging or other measures may need to focus on drug use trajectories rather than relapse versus non-relapse.

The future of neuroimaging in addiction

In a recent study with neurologically disordered individuals, investigators cited five potential roles for neuroimaging with respect to dementia; (1) as a cognitive neuroscience research tool, (2) for prediction of which normal or slightly impaired individuals will develop dementia and over what time frame, (3) for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in demented individuals, (sensitivity) and separation of AD from other forms of dementia (specificity), (4) for monitoring of disease progression, and (5) for monitoring response to therapies 99. Interestingly, neurologists have shown that lower motor cortex activation using fMRI was the best predictor of improvement and increases in motor cortex activation after treatment for stroke 86. Such roles are not unlike those that we would like to see implemented in the field of addiction. Substance dependent individuals comprise a heterogeneous group for which the factors reviewed above contribute to individual outcomes. The value of functional neuroimaging on its own compared to clinical, socio-demographical and neuropsychological variables for the prediction of relapse in substance abuse has not been clearly delineated. A combination of data from all those modalities, however, may soon enable the clinician to deduce individual predictions, even though current imaging studies rely on group analyses. Further, other functional brain imaging techniques such as PET, SPECT and MEG have already proven their relevance in predicting mild cognitive impairment 100 and depression 101 and may also be useful for the prediction of relapse to stimulant use. Predictions for clinical outcomes based on fMRI data could already be made in a limited number of published studies. It has been hypothesized that predictions of therapy-related behavioral gains may most accurately be achieved when acquiring both baseline measures of brain function and clinical variables 86. Drug cue-induced brain activation can distinguish between subjects subsequently abstinent or relapsing 102 and can be a better predictor of relapse than subjective reports of craving 78. Once functional imaging has been adopted into prediction processes, researchers will have to evaluate its use to select potential subsequent treatments. Brain function data can also help to trigger special clinical interventions. Neurofeedback, for example, may offer a promising tool to increase or suppress abnormalities in neural activity that could enhance individuals’ abilities to abstain from substances.

In order for neuroimaging to play a critical clinical role for predicting outcomes in substance use disorders, its sensitivity and specificity must be documented. Thus far, most imaging studies have revealed intriguing systems neuroscience results at the level of groups of subjects. These findings, by themselves, are insufficient to help move imaging forward as a clinically-relevant tool. On the other hand, most imaging studies have demonstrated surprisingly large effect sizes, which supports the idea that differences across individuals and across time within individuals may be large enough to provide meaningful results when measured on a subject-by-subject basis. To be useful as an illness severity marker or relapse predictor, neuroimaging measures need to closely track disease state both when it is symptomatic as well as when the disorder is asymptomatic. Thus, it is not sufficient to show that ill individuals differ from healthy subjects but also that recovered or asymptomatic individuals with substance use disorders have altered processing in specific brain structures when compared to those individuals without substance use disorders. Such consistent distinctions would thus enable us to make clinical predictions about individuals who are at high risk for experiencing exacerbation of substance use symptoms. As others have pointed out, combining neuroimaging approaches within medications studies of cocaine abusers could prove useful for targeting specific pharmacological agents to subgroups of patients, prediction of response to medication and relapse to use 103. Clearly, functional neuroimaging is playing an important role in substance use disorder research. In order for this modality to be useful for defining diagnostic categories or monitoring treatment success, we need to push the limits of this technology to clearly show its ability to define clinically-relevant information on a single-subject basis.

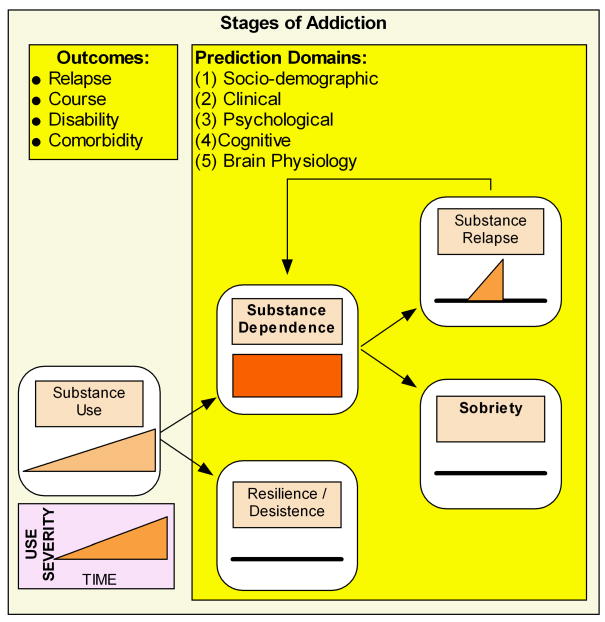

Figure 1.

Schematic for different stages of addictions. The goal for prediction tools in general and neuroimaging tools in particular is to be able to quantify the transitions with high positive and negative predictive value.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from NIDA (R01DA016663, R01DA018307) and by a VA Merit Grant.

References

- 1.Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2007:1–282. NSDUH Series H-32, DHHS Publication No. SMA 07–4293. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland P, Mushinski M. Costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States, 1992. Alcohol/Drugs COI Study Team. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1999;80:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucholz KK. Nosology and epidemiology of addictive disorders and their comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:221–240. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sareen J, Chartier M, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Illicit drug use and anxiety disorders: Findings from two community surveys. Psychiatry Res. 2006 May 30;142:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najavits LM, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Butler SF, Barber JP, Thase ME, Crits-Christoph P. Six-month treatment outcomes of cocaine-dependent patients with and without PTSD in a multisite national trial. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:353–361. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moran P. The epidemiology of antisocial personality disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:231–242. doi: 10.1007/s001270050138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raimo EB, Smith TL, Danko GP, Bucholz KK, Schuckit MA. Clinical characteristics and family histories of alcoholics with stimulant dependence. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:728–735. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Substance use disorder and personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:25–29. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Westerberg VS, Harris RJ, Tonigan JS. What predicts relapse? Prospective testing of antecedent models. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):S155–S172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donovan DM. Assessment issues and domains in the prediction of relapse. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):S29–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marlatt G Alan, Gordon Judith R. Relapse prevention : maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litman GK, Stapleton J, Oppenheim AN, Peleg M, Jackson P. The relationship between coping behaviours, their effectiveness and alcoholism relapse and survival. Br J Addict. 1984;79:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Craig B Martha. Cognitive and behavioral coping strategies in the reappraisal of stressful social situations. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1976;23:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rollnick S, Heather N. The application of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory to abstinence-oriented alcoholism treatment. Addict Behav. 1982;7:243–250. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annis HM. A cognitive-social learning approach to relapse: pharmacotherapy and relapse prevention counselling. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1991;1:527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Donovan DM. Conceptualizations of relapse: a summary of psychological and psychobiological models. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):S5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon RL. The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: the costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. Am Psychol. 1980;35:691–712. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig AM, Wikler A, Stark LH. The first drink: psychobiological aspects of craving. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30:539–547. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760100093015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wise RA. The neurobiology of craving: implications for the understanding and treatment of addiction. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:118–132. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mossberg D, Liljeberg P, Borg S. Clinical conditions in alcoholics during long-term abstinence: a descriptive, longitudinal treatment study. Alcohol. 1985;2:551–553. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(85)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crosby RD, Halikas JA, Carlson G. Pharmacotherapeutic interventions for cocaine abuse: present practices and future directions. J Addict Dis. 1991;10:13–30. doi: 10.1300/J069v10n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The psychology and neurobiology of addiction: an incentive-sensitization view. Addiction 95 Suppl. 2000;2:S91–117. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller WR. What is a relapse? Fifty ways to leave the wagon. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):S15–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everitt BJ, Dickinson A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychological basis of addictive behaviour. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997 Oct 3;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenwood GL, Woods WJ, Guydish J, Bein E. Relapse outcomes in a randomized trial of residential and day drug abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callaghan RC, Cunningham JA. Gender differences in detoxification: predictors of completion and re-admission. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frawley PJ, Smith JW. One-year follow-up after multimodal inpatient treatment for cocaine and methamphetamine dependencies. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:271–286. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon RC. Personality, stress, and social support in cocaine relapse prediction. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, Nich C, Jatlow P, Bisighini RM, Gawin FH. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:177–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Fletcher BW, Hubbard RL, Anglin MD. A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:507–514. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brecht ML, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Predictors of relapse after treatment for methamphetamine use. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:211–220. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snow D, Anderson C. Exploring the factors influencing relapse and recovery among drug and alcohol addicted women. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2000;38:8–19. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20000701-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan PL, Kagay CR, Geppert JJ, Moos RH. Predictors and outcomes of outpatient mental health care: a 4-year prospective study of elderly Medicare patients with substance use disorders. Med Care. 2001;39:39–49. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant BF. Prevalence and correlates of drug use and DSM-IV drug dependence in the United States: results of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8:195–210. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisner C, Ray GT, Mertens JR, Satre DD, Moore C. Short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes predict long-term outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Sep 10;71:281–294. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yucel M, Lubman DI. Neurocognitive and neuroimaging evidence of behavioural dysregulation in human drug addiction: implications for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:33–39. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKay JR, Weiss RV. A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups. Preliminary results and methodological issues. Eval Rev. 2001;25:113–161. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Leary TA, Rohsenow DJ, Martin R, Colby SM, Eaton CA, Monti PM. The relationship between anxiety levels and outcome of cocaine abuse treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:179–194. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewer DD, Catalano RF, Haggerty K, Gainey RR, Fleming CB. A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction. 1998;93:73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ingersoll KS, Lu IL, Haller DL. Predictors of in-treatment relapse in perinatal substance abusers and impact on treatment retention: a prospective study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1995;27:375–387. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1995.10471702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyman SE, Malenka RC. Addiction and the brain: the neurobiology of compulsion and its persistence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:695–703. doi: 10.1038/35094560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anton RF. What is craving? Models and implications for treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartz DT, Frederick-Osborne SL, Galloway GP. Craving predicts use during treatment for methamphetamine dependence: a prospective, repeated-measures, within-subject analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001 Aug 1;63:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schonfeld L, Rohrer GE, Dupree LW, Thomas M. Antecedents of relapse and recent substance use. Community Ment Health J. 1989;25:245–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00754441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawkins EJ, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR. 12-13-2007 Concurrent monitoring of psychological distress and satisfaction measures as predictors of addiction treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers MG, Brown SA, Mott MA. Coping as a predictor of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. J Subst Abuse. 1993;5:15–29. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90120-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solomon KE, Annis HM. Outcome and efficacy expectancy in the prediction of post-treatment drinking behaviour. Br J Addict. 1990;85:659–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCormick RA, Dowd ET, Quirk S, Zegarra JH. The relationship of NEO-PI performance to coping styles, patterns of use, and triggers for use among substance abusers. Addict Behav. 1998;23:497–507. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher LA, Elias JW, Ritz K. Predicting relapse to substance abuse as a function of personality dimensions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1041–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cannon DS, Keefe CK, Clark LA. Persistence predicts latency to relapse following inpatient treatment for alcohol dependence. Addict Behav. 1997;22:535–543. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin H, Rourke SB, Patterson TL, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Predictors of relapse in long-term abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:640–646. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verdejo-Garcia A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, Perez-Garcia M. Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Dec 1;91:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller L. Predicting relapse and recovery in alcoholism and addiction: neuropsychology, personality, and cognitive style. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1991;8:277–291. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90051-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sussman S, Rychtarik RG, Mueser K, Glynn S, Prue DM. Ecological relevance of memory tests and the prediction of relapse in alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47:305–310. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tapert SF, Baratta MV, Abrantes AM, Brown SA. Attention dysfunction predicts substance involvement in community youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:680–686. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cox WM, Hogan LM, Kristian MR, Race JH. 12-1-2002 Alcohol attentional bias as a predictor of alcohol abusers’ treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 68:237. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00219-3. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wehr A, Bauer LO. Verbal ability predicts abstinence from drugs and alcohol in a residential treatment population. Psychol Rep. 1999;84:1354–1360. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. P300 decrements in teenagers with conduct problems: implications for substance abuse risk and brain development. Biol Psychiatry. 1999 Jul 15;46:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Hall JM. Polysomnographic and subjective sleep predictors of alcoholic relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1864–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Allsop S. Relapse prevention and management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1990;9:143–153. doi: 10.1080/09595239000185201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Passetti F, Clark L, Mehta MA, Joyce E, King M. 12-4-2007 Neuropsychological predictors of clinical outcome in opiate addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, De Beurs E, van den Brink W. The role of self-reported impulsivity and reward sensitivity versus neurocognitive measures of disinhibition and decision-making in the prediction of relapse in pathological gamblers. Psychol Med. 2008;38:41–50. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verdejo-Garcia A, Rivas-Perez C, Vilar-Lopez R, Perez-Garcia M. Strategic self-regulation, decision-making and emotion processing in poly-substance abusers in their first year of abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Jan 12;86:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paulus MP. Decision-making dysfunctions in psychiatry--altered homeostatic processing? Science. 2007 Oct 26;318:602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.1142997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shulman RG, Hyder F, Rothman DL. Biophysical basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35:287–325. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogawa S, Lee TM. Magnetic resonance imaging of blood vessels at high fields: in vivo and in vitro measurements and image simulation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1990;16:9–18. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogawa S, Lee TM, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1990;14:68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hyder F, Kida I, Behar KL, Kennan RP, Maciejewski PK, Rothman DL. Quantitative functional imaging of the brain: towards mapping neuronal activity by BOLD fMRI. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:413–431. doi: 10.1002/nbm.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buxton RB, Uludag K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S220–S233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kastrup A, Kruger G, Glover GH, Neumann-Haefelin T, Moseley ME. Regional variability of cerebral blood oxygenation response to hypercapnia. Neuroimage. 1999;10:675–681. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paulus MP, Hozack N, Zauscher B, McDowell JE, Frank L, Brown GG, Braff DL. Prefrontal, Parietal, and Temporal Cortex Networks Underlie Decision-Making in the Presence of Uncertainty. Neuroimage. 2001;13:91–100. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kosten TR, Scanley BE, Tucker KA, Oliveto A, Prince C, Sinha R, Potenza MN, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE. Cue-induced brain activity changes and relapse in cocaine-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:644–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Seiferth NY, Pauly K, Habel U, Kellermann T, Jon Shah N, Ruhrmann S, Klosterkotter J, Schneider F, Kircher T. 11-28-2007 Increased neural response related to neutral faces in individuals at risk for psychosis. Neuroimage. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brahmbhatt SB, Haut K, Csernansky JG, Barch DM. Neural correlates of verbal and nonverbal working memory deficits in individuals with schizophrenia and their high-risk siblings. Schizophr Res. 2006;87:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Schuckit MA. Neural activation patterns of methamphetamine-dependent subjects during decision making predict relapse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:761–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sinha R, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Fulbright RK, Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Wexler BE. Neural activity associated with stress-induced cocaine craving: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grusser SM, Wrase J, Klein S, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Ruf M, Weber-Fahr W, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Heinz A. Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siegle GJ, Carter CS, Thase ME. Use of FMRI to predict recovery from unipolar depression with cognitive behavior therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:735–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, Bray P, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J. Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: Functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:144–152. doi: 10.1017/s0007125000161872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cramer SC, Parrish TB, Levy RM, Stebbins GT, Ruland SD, Lowry DW, Trouard TP, Squire SW, Weinand ME, Savage CR, Wilkinson SB, Juranek J, Leu SY, Himes DM. Predicting functional gains in a stroke trial. Stroke. 2007;38:2108–2114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Richardson MP, Strange BA, Duncan JS, Dolan RJ. Memory fMRI in left hippocampal sclerosis: optimizing the approach to predicting postsurgical memory. Neurology. 2006 Mar 14;66:699–705. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201186.07716.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McIntosh AR, Bookstein FL, Haxby JV, Grady CL. Spatial pattern analysis of functional brain images using partial least squares. Neuroimage. 1996;3:143–157. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guo Y, Dubois Bowman F, Kilts C. 10-9-2007 Predicting the brain response to treatment using a Bayesian hierarchical model with application to a study of schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neale MC, Aggen SH, Maes HH, Kubarych TS, Schmitt JE. Methodological issues in the assessment of substance use phenotypes. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1010–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE. Genetic studies of substance abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000 May 1;59:101–123. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chi FW, Weisner CM. Nine-year psychiatric trajectories and substance use outcomes: an application of the group-based modeling approach. Eval Rev. 2008;32:39–58. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xie H, Drake R, McHugo G. Are there distinctive trajectory groups in substance abuse remission over 10 years? An application of the group-based modeling approach. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:423–432. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Harley RM, Xian H, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True WR, Faraone SV. Genetic and environmental influences on transitions in drug use. Behav Genet. 1999;29:473–479. doi: 10.1023/a:1021635223370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Clark DB, Jones BL, Wood DS, Cornelius JR. Substance use disorder trajectory classes: diachronic integration of onset age, severity, and course. Addict Behav. 2006;31:995–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Trajectories of concurrent substance use disorders: a developmental, typological approach to comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:902–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chertkow H, Black S. Imaging biomarkers and their role in dementia clinical trials. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34(Suppl 1):S77–S83. doi: 10.1017/s031716710000562x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Matsuda H. The role of neuroimaging in mild cognitive impairment. Neuropathology. 2007;27:570–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gemar MC, Segal ZV, Mayberg HS, Goldapple K, Carney C. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow following mood challenge in drug-free, remitted patients with unipolar depression. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:597–601. doi: 10.1002/da.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McClernon FJ, Hiott FB, Liu J, Salley AN, Behm FM, Rose JE. Selectively reduced responses to smoking cues in amygdala following extinction-based smoking cessation: results of a preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Addict Biol. 2007;12:503–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Elkashef A, Vocci F. Biological markers of cocaine addiction: implications for medications development. Addict Biol. 2003;8:123–139. doi: 10.1080/1355621031000117356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]