Abstract

Purpose

Clear and complete communication between health care providers is a prerequisite for safe patient management and is a major priority of the Joint Commission's 2008 National Patient Safety Goals. The goal of this study was to describe nurses' perceptions of nurse-physician communication in the long-term care (LTC) setting.

Methods

Mixed-method study including a self-administered questionnaire and qualitative semi-structured telephone interviews of licensed nurses from 26 LTC facilities in Connecticut. The questionnaire measured perceived openness to communication, mutual understanding, language comprehension, frustration, professional respect, nurse preparedness, time burden and logistical barriers. Qualitative interviews focused on identifying barriers to effective nurse-physician communication that may not have previously been considered and eliciting nurses' recommendations for overcoming those barriers.

Results

Three-hundred seventy-five (375) nurses completed the questionnaire and 21 nurses completed qualitative interviews. Nurses identified several barriers to effective nurse-physician communication: lack of physician openness to communication, logistic challenges, lack of professionalism, and language barriers. Feeling hurried by the physician was the most frequent barrier (28%), followed by finding a quiet place to call (25%) and difficulty reaching the physician (21%). In qualitative interviews, there was consensus that nurses needed to be brief and prepared with relevant clinical information when communicating with physicians and that physicians needed to be more open to listening.

Conclusions

A combination of nurse and physician behaviors contributes to ineffective communication in the LTC setting. These findings have important implications for patient safety and support the development of structured communication interventions to improve quality of nurse-physician communication.

Keywords: Communication, physician-nurse relationships, patient safety, nursing home, telephone

Introduction

Clear and complete communication between health care providers is a prerequisite for safe patient management and is a key component of the Joint Commission's 2008 National Patient Safety Goals for Long-Term Care (LTC).1 The Institute of Medicine's report “To Err is Human”2 underscores the role of ineffective communication as a significant contributing factor in medical error, with communication failures at the root of over 60% of sentinel events reported to the Joint Commission.3 Communication between healthcare workers accounts for the major part of the information flow in healthcare and growing evidence indicates that errors in communication impact on patient safety.4, 5 Specifically, there is evidence from a variety of healthcare settings, including the operating room6, the intensive care unit,7, 8 and the nursing home setting9, 10 that poor nurse-physician communication adversely affects patient care.

Previous studies have described the challenges of effective nurse-physician communication in the inpatient setting, the intensive care unit setting and in ambulatory practice.11-14 Of the studies that have focused on nurse-physician communication in LTC setting, few specifically focus on telephone communication.9, 15-18 The paucity of studies focusing on telephone communication is a significant shortcoming since communication in the LTC setting heavily relies on telephone communication.17 Telephone communication occurs more often in LTC than in other clinical settings, and many calls occur after hours and on weekends to covering physicians.17, 19 As a result, important clinical decisions are being made by physicians who are relying on information from the nurse on the telephone because the physician is unfamiliar with the patient.20 For these reasons, it is important to better understand barriers to optimal nurse-physician communication on the telephone that compromise care delivery and to identify strategies for improving this form of communication.

To address these issues, we conducted a mixed-methods study to identify and quantify barriers to effective nurse-physician communication on the telephone in the LTC setting and to identify strategies for overcoming these barriers. Specifically, we used a quantitative approach to describe the frequency with which LTC nurses identified specific barriers to nurse-physician communication, with the advantage of assessing the relative magnitude of different barriers based on previously reported and hypothesized barriers to communication. To complement this approach, we used qualitative interviews to elaborate on and probe for previously unidentified communication barriers by exploring nurses' views on challenging nurse-physician telephone encounters. Further, we used the qualitative interviews to elicit strategies to improve nurse-physician communication and overcome barriers to telephone communication. In this way, we sought to advance patient safety by improving our understanding of how to improve nurse-physician communication in the LTC setting.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a mixed-method study that included two separate components: a self-administered questionnaire and a semi-structured qualitative telephone interview among a subsample of questionnaire respondents. The mixed-method approach has the advantage of combining the strengths of the quantitative approach (i.e. assessing the magnitude and relative frequency of known phenomena) with the strengths of the qualitative approach (i.e. identifying and exploring phenomena unmeasured by quantitative methods), with the combined approach allowing for meaningful inferences resulting from the integration and comparison of the results from each part of the study.21, 22 The use of the interview format allowed for the exploration of individual experiences with nurse-physician communication among nurses with varied levels of experience, language skills and demographic characteristics.

Study Population

Our target population was all licensed nurses at 26 Connecticut nursing homes. The homes had been recruited to participate in an intervention study evaluating the effectiveness of a standardized communication intervention to improve the quality and safe management of warfarin therapy in the LTC setting. Nurses were eligible for participation if they provided more than 8 hours of direct patient care per month as reported by the facilities' director of nursing.

Quantitative Data Collection

Questionnaire Development

We developed a questionnaire to assess nurse-physician communication in the LTC setting. The questionnaire was adapted from the Schmidt nursing home quality of nurse-physician communication scale used in Sweden.10 We reviewed and adapted eight of the eighteen items from the Schmidt instrument, and created ten new items specifically addressing aspects of telephone communication, resulting in an 18-item questionnaire. Questions addressed aspects of communication previously described in the published literature, including openness, mutual understanding and language comprehension, frustration with the interaction and professional respect, nurse preparedness, time burden and logistical barriers to communication.10, 15 Questions were rated on a 5-point Likert scale [range 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always)]. Content validity was assessed by an interdisciplinary panel composed of two nurses and two geriatricians who reviewed each of the items, and assessed the appropriateness of item wording and content; all items on the final version of the questionnaire were approved by the full panel. Pilot testing with the final questionnaire was conducted with two nurses who had extensive experience in the LTC setting to ensure the items were appropriate for LTC nurses in the United States.

Demographic information collected included age, whether English was their first language, race/ethnicity, level of training, job title, typically assigned shift, tenure as a nurse and length of employment in long-term care.

Data Collection Procedures

Questionnaires and instructions were sent to all eligible licensed nursing staff via the staff development nurse or nursing supervisor at each facility. Respondents were asked to complete and return the anonymous questionnaires directly to the central research office. Each questionnaire included a coffee gift certificate as an incentive. In order to maintain confidentiality, no identifying information was included. We were therefore unable to contact non-respondents. However, to increase our response rate, we requested that a second batch of questionnaires be distributed within each facility to nurses who self-reported non-response to the first request.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the study population and to summarize the proportion of nurses who endorsed each barrier to communication on the questionnaire. Responses to instrument items measured on the 5-point Likert scale were dichotomized into yes and no by defining yes as a response of 4 or 5. To assess the effect of the response rate on the summary results of the item responses, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that stratified item responses by facility response rate (i.e. lower response rate facilities [defined as facility response rate lower than actual response rate] versus higher response rate facilities). We used a Chi-square test to assess for statistically significant differences in each item response by facility response rate. Quantitative analyses were conducted with STATA SE (version 10.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Qualitative Data Collection

Semi-Structured Telephone Interviews

Respondents to the questionnaire were asked if they were interested in participating in a follow-up semi-structured telephone interview. Of those who expressed interest, we invited a subset to participate in telephone interviews. The sampling strategy was to include a combination of a random sample of 10 respondents and a selective sample of at least 10 respondents that captured a representative distribution of age, sex, nurse tenure, and language ability in the overall interview sample.23 Our final qualitative sample included 21 (10 randomly sampled and 11 selectively sampled) nurses. All participants completed informed consent procedures and had their interview tape recorded and transcribed for analysis. A typical interview lasted about 15-20 minutes.

During the interview, a trained interviewer asked the following questions: “Think about the last time that you found it difficult to communicate with a physician. Please briefly describe what happened.”; “In your opinion, what prevents effective nurse-physician communication?”; “What have you found to be particularly helpful in improving nurse-physician communication? What tips might you give a new nurse?”; “What do you wish physicians would do differently when communicating with you?”.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Content analysis of the interview transcripts was performed following the guidelines offered by Krueger.24 One author (JT) reviewed all 21 transcripts and proposed a framework for extracting major themes related to nurse-physician communication in the context of telephone use in the long-term care setting. Each investigator then read at least 3 transcripts and compared the themes in those transcripts with the proposed framework. All the authors met to discuss and revise the framework. This process continued iteratively until all authors agreed that all themes and dimensions regarding nurse-physician communication had been identified, and that the framework provided a reasonable depiction of the process of communication and factors affecting nurse-physician communication as stated or implied by participants. Finally, each transcript was re-read by 2 authors, who coded comments using the revised framework. Authors also identified exemplary comments and confirmed that the final framework accommodated each important comment related to nurse-physician communication.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

We received a total of 325 completed questionnaires. This sample represents 26% of the nurses at all participating facilities. Useable questionnaires were received from all facilities, with the individual facility response rate ranging from 4% to 54%. When we compared the proportion of nurses endorsing each communication barrier by facility response rate (i.e. higher [n=15] vs lower [n=11] response rate facilities), we found no statistically significant difference in the proportions endorsing each response. (Data not shown.) For this report, we present the aggregated responses of nurses from all facilities.

Respondent characteristics of the questionnaire sample are presented in Table 1. The majority of the sample (59%) was aged 45-64 years old and had been working as a nurse for over ten years (74%). The majority (76%) of nurses reported their race/ethnicity as white and that English was their primary language (86%). There were a total of 21 qualitative interviews. The characteristics of the interview participants were similar to that of the respondents in terms of demographics, experience, and language abilities. (Table 1)

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Questionnaire Respondents N = 325 |

% | Telephone Interviewees N=21 |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 18-24 | 2 | <1 | 1 | 5 |

| 25-44 | 117 | 36 | 9 | 43 |

| 45-64 | 190 | 59 | 9 | 43 |

| 65+ | 11 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 247 | 76 | 14 | 67 |

| Black | 24 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 33 | 10 | 4 | 19 |

| American Indian or Alaskan | 2 | <1 | 1 | 5 |

| Native | ||||

| Other | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Degree | ||||

| Registered Nurse | 180 | 55 | 13 | 62 |

| Licensed Practical Nurse | 138 | 43 | 8 | 38 |

| Nurse Practitioner or Clinical | 2 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nurse Specialist | ||||

| Other | ||||

| Facility Role/Job Title* | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Supervisor, Assistant Director | 72 | 22 | 6 | 29 |

| Of Nursing | ||||

| Unit Manager | 95 | 29 | 3 | 14 |

| Specialty (MDS, Infection Control/QI/Wound Management) | 16 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Staff | 123 | 38 | 10 | 48 |

| Agency or Per diem | 18 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 35 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Tenure as Nurse | ||||

| < 1year | 9 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 1 year-5 years | 26 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| 5-10 years | 49 | 15 | 3 | 14 |

| >10 years | 239 | 74 | 16 | 76 |

| Missing | 2 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| English as First Language | ||||

| Yes | 278 | 86 | 17 | 81 |

| No | 41 | 12 | 4 | 19 |

| Missing | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Roles not mutually exclusive

Questionnaire Findings

Table 2 provides data on barriers to communication by frequency and communication domain.

Table 2. Barriers to Nurse-Physician Communication, Ranked by Frequency.

| Barrier | N* | % |

|---|---|---|

| Openness/Collaboration | ||

| Nurse feels hurried by the physician† | 91 | 28 |

| Nurse feels that the physician doesn't want to deal with the problem† | 55 | 17 |

| Physicians do not consider nurses' views when making decisions about patients. | 42 | 13 |

| Nurse worries that the physician may order something inappropriate or unnecessary† | 18 | 6 |

| Logistic Challenges | ||

| Nurse finds it hard to find a quiet place to make the call† | 80 | 25 |

| Nurse has difficulty reaching the physician† | 68 | 21 |

| Nurse feels doesn't have enough time to say everything that needs to be said† | 55 | 17 |

| Nurse finds it hard to find time to make the call† | 51 | 16 |

| Professional Respect/Frustration | ||

| Nurse anticipates that the physician will be rude or unpleasant† | 55 | 17 |

| Physicians interrupt before nurse has finished reporting on a patient. | 52 | 16 |

| Nurse feels disrespected after an interaction with a physician | 53 | 16 |

| Nurse feels physicians are rude when called about a patient? | 42 | 13 |

| Nurse feels frustrated after an interaction with a physician | 32 | 10 |

| Language/Mutual Understanding | ||

| Nurse finds physician's language or accent make it hard to understand what they are saying. | 32 | 10 |

| Nurse has difficulty understanding what a physician means due to medical jargon. | 9 | 3 |

| Nurse feels physician has difficulty understanding what nurse is saying due to nurse's language or accent | 7 | 2 |

| Nurse Preparedness | ||

| Nurse feels that she/he is bothering the physician† | 78 | 24 |

| Nurse is uncertain about what to tell the physician† | 9 | 3 |

Rating a 4 or 5 where 5 was labeled “almost always”

Response to the question: “How often does each of the following make it hard for you to talk with a physician over the telephone?”

Openness/Collaborativeness

The most frequently reported characteristic of communication making it hard for nurses to talk with physicians on the telephone was feeling hurried by the physician (28%). Many (17%) reported that they felt the physician did not want to deal with the problem and about 13% reported that physicians do not take nurse views into consideration when managing patients.

Logistic Challenges

Finding a quiet place to call was the second most frequently reported barrier to communication (25%). Over 20% of the responding nurses also reported difficulty reaching the physician and delays in call back as a barrier. Finding time to make a call was a barrier reported by about 15% of respondents.

Professional Respect and Frustration

Approximately 13-17% of nurses reported encounters that were characterized by rudeness and disrespect from the physician. Many nurses reported that the physician interrupted before the nurse had finished reporting on a patient (16%). One in ten nurses reported feeling frustrated after interactions with a physician.

Language/Mutual Understanding

Language barriers were the least frequently reported barrier to effective communication. About 10% of nurses reported that understanding a physician due to language or accent was a problem, and very few (3%) reported that the use of medical jargon was a problem.

Nurse Preparedness

Very few nurses (3%) felt uncomfortable determining what to report to the physician during a telephone encounter, but many felt that that they were bothering the physician by making a telephone call (24%).

Interview Findings

Nurses offered numerous examples of difficult nurse-physician communication encounters during the interviews. Thematic analysis of nurses' comments revealed many themes characterizing difficult encounters that were also captured in the questionnaires: feeling hurried by the physician, experiencing disrespect from a physician, lack of physician openness to nurse input, and language barriers. However, the interviews also revealed themes that were not elicited in the questionnaire, including challenges in working with a covering physician, lack of physician responsiveness and lack of trust between care providers. In addition, the issue of nurse preparedness emerged as a dominant theme in the interviews. In the following section of our paper, we expand on the theme of nurse preparedness and other themes not revealed in the survey responses.

Nurse Preparedness

Nurses frequently (n=15/21 interviews) described a lack of nurse preparedness for telephone calls as a factor contributing to challenging nurse-physician communication encounters.

“I think if you are calling a physician you should be prepared at least with immediate information. They shouldn't have to wait while you call them back with a set of vitals or something like that…. I think that's a failing on the nurse's side of things.”

Challenges of Working with Covering Physicians

Nurses described several challenges to discussing patient management issues with covering physicians who were not familiar with the patient. Not infrequently, nurses encountered physicians who they perceived as angry that the issue was not addressed during business hours.

“The on-call doctor was very upset that I did not call before 5 o'clock and I said to him that I will make sure I will tell my patients to bleed between the hours of 9 and 5.”

Nurses also encountered covering physicians who appeared reluctant to get involved in the management of these patients.

“When there is a covering doctor, they are very reluctant to order on a patient because they will say that they don't know the patient. But we just tell them we need an answer because sometimes [the patient's doctor] will be away for a couple of days.”

Trust between Healthcare Providers

Several issues of relating to trust between healthcare providers also arose in the management of patients.

“When a nurse knows a doctor and the doctor knows the nurse and they trust each other, that's the best communication there is going to be. When it's a strange nurse or strange doctors… then I think that's your major barrier to communication.”

Lack of Physician Responsiveness

Many nurses described several aspects of physicians' responses to telephone encounters that hindered effective communication. Most notably, many physicians did not call back or were unable to be reached. Some nurses also pointed out that delayed call-backs by the physician contributed to lack of information by the nurse.

“In general, probably the worst thing is just not being prepared… but 9 times out of 10 you are not going to get [a certain doctor] when you call. When you do speak to him, you don't have the chart right in front of you because you never expected to talk to him.”

Another barrier nurses described were problems with physicians clearly and completely conveying their message. For example, nurses noted that physicians sometimes provide incomplete orders or instructions, or refused to clarify orders or underlying rationales for management decisions.

Recommendations for Improving Nurse-Physician Communication

We used the qualitative interviews to ask nurses what they wished physicians would do differently when communicating with nurses and what they thought nurses should do differently to improve communication.

Recommendations for Physicians

Nurse felt that physicians could contribute to improving nurse-physician communication by maintaining a professional demeanor and respecting nurses more. They also recommended that physicians recognize that the nurse often knows the patient well and be willing to work more collaboratively with nurses. Nurses wished that physicians would call back promptly and that they would listen to the nurses more when they do call.

Recommendations for Nurses

When asked what they would recommend to improve nurse-physician communication, the overwhelming recommendation was to be prepared.

“I think if you're prepared and have all the information needed when you talk to a doctor, it makes it go that much smoother.”

Other important recommendations for nurses were to communicate clearly, to explain the reason for the call when it is policy or protocol driven, and to clearly state what is needed from the physician. Nurses felt it was important to be persistent, clear and professional with physicians who were not responding to calls promptly or addressing the clinical issue at hand. One nurse emphasized “remember that the safety of the patient is the most important thing.”

Finally, nurses suggested strategies to eliminate unnecessary calls to physicians. These strategies included bundling calls to prevent redundant calls, addressing issues while the physician was in the facility if possible, and appropriately triaging calls to the next business day when possible.

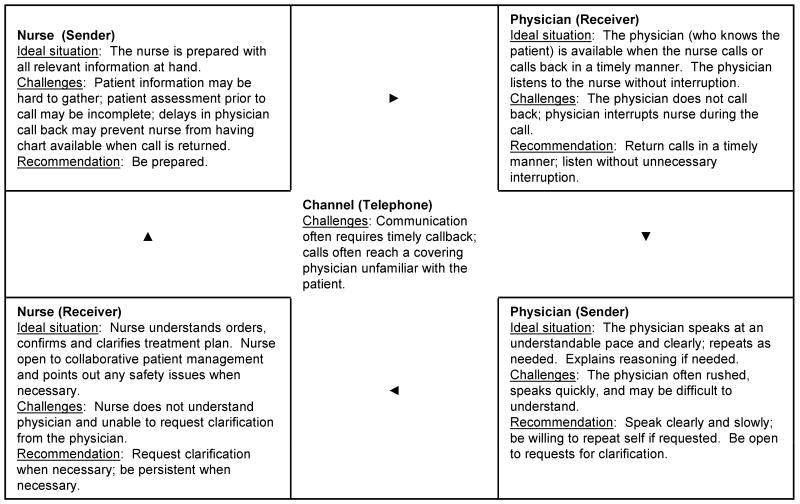

The combination of our quantitative and qualitative findings can be understood in the context of the Communication-Human Information Processing (C-HIP) model which provides a useful framework for considering breakdowns in communication of information to physicians.25 Although other models have been applied to analyzing nurse-physician communication from an organizational context, including structural, human response, political and cultural models26, we use the C-HIP model since it is often applied to communication of warning information and has been found useful in other studies about patient safety and communication with physicians.27 Applying this model to the communication between nurses and physicians reveals possible reasons for failure of the communication process and facilitates identification of possible solutions.

The model is diagramed in Figure 1 and describes information as proceeding from a sender (e.g. a nurse), through a channel (e.g. the telephone), to a receiver (e.g. a physician), before potentially affecting behavior (e.g. prescribing). Within the receiver, information processing passes through four substages: attention, comprehension, attitudes/beliefs and motivation. Processing can be impeded at any stage or substage. The issues associated with each information exchange stage, including the ideal situation and challenges to that information exchange, are summarized in Figure 1. It is important to note that the stages are all inter-related and that feedback loops are implied at every stage. For instance, the receiver's perceptions of the sender may affect both attention and motivation, thereby affecting the receiver's ability to listen clearly. Similarly, the receivers' attitude (e.g. professionalism) may affect attention (e.g. ability to listen to speaker without interruption). Thus, while the recommendations in Figure 1 are associated with particular stages, a given change at any stage or information exchange point may influence processing at multiple stages, any or all of which may impact the effectiveness of the communication process. The integrated quantitative and qualitative findings of our study, as contextualized in the C-HIP model, can be summarized by the following interview quote:

Figure 1. Communication-Health Information Processing (C-HIP) Model of Nurse-Physician Telephone Communication in the Long-Term Care Setting.

“I think it's a two way street, really. I think sometimes it's the attitude on the part of the physicians. They are tired. They don't want to be bothered…. then a nurse that calls who is not prepared. I think sometimes those are the things that lead to misunderstanding. I do think it is a two-way street. …we need to be respectful of each other.”

Discussion

Using a mixed-methods approach to assess barriers to nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting, we found an interesting contrast between the perceived importance of nurse preparedness as a barrier to nurse-physician communication in the two parts of our study: the quantitative questionnaire suggested that nurse preparedness was one of the least important barriers, while the qualitative interviews indicated it to be one of the most important barriers. Further, interviews with nurses revealed that inadequate nurse preparedness could be the result of, or exacerbated by, physician behavior such as delayed response to telephone calls and physician interruptions. Taken together, a key result of our study is the C-HIP model that helps to describe impaired nurse-physician telephone communication in terms of a two-way professional interaction dependent on interrelationships of preparedness, responsiveness, collaborativeness and professionalism. The C-HIP framework highlights the importance of the interrelatedness of interactions and susceptibility of the system to communication breakdowns, and suggests several recommendations for improvement that can ultimately contribute to improved quality of patient care and patient safety.

The results of both the quantitative and qualitative parts of our study confirm the findings of previous studies in different settings that identify lack of professionalism 15, 28, 29, inadequate collaboration 30, lack of timely call backs by physicians9, 11, 31, 32, and physician disinterest31 as commonly occurring issues affecting nurse-physician communication. Our study also found that working with a covering physician, time constraints and nurse preparedness were issues of particular importance the LTC setting. For example, 17% of nurses in our study reported that physicians did not want to address problems in telephone calls, and that this was particularly true for covering physicians who did know know that patient. Very few studies have addressed the issue of communicating with covering physicians in the LTC setting31, but this finding underscores the importance of improving patient management via telephone encounters.

Nurse competency and preparedness are key components of nurse-physician communication about patient issues. The quality of nurse preparedness reported in the literature depends, in part, on whether nurses or physicians were asked about its quality. Cadogan et al found that physicians perceived nurse competence to be a significant communication barrier while nurses did not.15 In Cadogan's study, nurses felt that they knew how to assess a resident before calling a physician and that their explanations of the residents' problems were clear, concise and complete, but physicians did not agree. In our study, interviewed nurses believed that their nurse colleagues were often unprepared when calling physicians, and that this negatively affected nurse-physician communication. Further, nurses in our study agreed that the most important thing a nurse could do to improve communication effectiveness was to be prepared.

However, our study also revealed that lack of a timely call back by the physician contributed to suboptimal nurse preparedness because the nurse would be less likely to have the information on hand if they waited a long time to speak with the physician. This reliance on synchronous communication (i.e., immediate contact with another person), particularly when it is impaired by a delayed call back, can push the limits of human memory in an interrupt-driven environment.4 That is, in the LTC setting where nurses are often interrupted in the execution of their daily responsibilities, a delay between the preparation and delivery of a patient assessment can interfere with the ultimate quality of the information being communicated.4 When contextualized in the C-HIP model of communication, the results of our study demonstrate an interrelatedness of communication interactions between nurses and physicians that affects communication quality.

Other physician behaviors commonly reported in our study also affect the quality of nurse-physician exchanges including physician interruptions during calls, physicians hurrying nurses, and physicians being rude. Such disruptive behavior has been previously described in other studies28, 29 and has been found to adversely affect patient safety, particularly when the opportunity to repeat and verify telephoned clinical information is curtailed.33, 34

Previous studies have suggested that differences in training and communication styles of nurses and physicians contributes to communication problems.15, 35 Efforts to create a shared mental model between physicians and nurses could improve interdisciplinary communication36 and foster “relationship coordination” (shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect) that may lead to improved patient outcomes.37 However, this does not obviate the need for physicians to be more willing to listen to nurses and work collaboratively as recommended by nurses in our qualitative interviews. Previous reports have found that nurse input can be poorly received by physicians,14, 38 even though improved collaboration contributes to better quality of care.13, 37

The findings of this study are important for three reasons. First, we have documented that the problem of nurse-physician communication continues to be an important issue despite almost 40 years of research and effort to improve nurse-physician communication in the LTC setting.16, 31, 39, 40 Second, the mixed-method approach allowed us to develop a communication framework highlighting the inter-relatedness of each stage of nurse-physician communication and its susceptibility to breakdown at any stage because of deficiencies on the part of either party. Third, we have identified some potential strategies to improve communication and the qualitative component of our study allowed us to capture and describe communication barriers that have not previously been well described, such as working with covering physicians.

The limitations of our study deserve comment. First, our study was conducted among a sample of nursing homes in Connecticut included by virtue of participation in a study to improve warfarin safety in the LTC setting. However, the distribution of age, experience as a nurse, and language abilities of the respondents in both components of our study suggest that our findings may be generalizable to the experiences of nurses working in the LTC setting. Second, we did not include physicians in our study, thus limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about physician-reported barriers to nurse-physician communication. Previous studies have described discrepancies between the perceptions of nurses and physicians15, and we acknowledge that an assessment of physician responses to our findings and recommendations warrants further study. Third, we did not report the reliability of the questionnaire items because we did not seek to assign scores to individual nurses or LTC facilities; typical analyses such as computation of Cronbach's alpha were outside the scope of this study. We recommend further psychometric assessment should the instrument be used to report scores or scales for each domain and for overall communication.

Unlike other studies, our study finds that nurses themselves recommend improved nurse preparedness as a key target for improving the effectiveness of nurse-physician communication in the LTC setting. There is evidence that clear communication is associated with improved quality of care and patient outcomes,4 and our findings suggest strategies for achieving clear and effective communication. We believe that the use of tools such as the American Medical Director Association's “Protocols for Physician Notification”41, an intervention that structures and informs the content of key clinical information necessary to reporting various clinical scenarios to physicians, are essential to improving clinical communication. Such tools can help overcome differences in communication styles between nurses and physicians that are a major factor contributing to inter-disciplinary communication difficulties.35 Also, structured communication techniques such as SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation), that format communication into highly distilled content and quick delivery format, are also increasingly being used in the healthcare setting to address both issues of complete content and time constraints. 36,42 Similar standardized approaches are being promoted by the National Patient Safety Foundation to assist organizations to improve clinical communication.43 At least one previous study has shown that decision support tools to aid LTC nurses with symptoms assessment and communication of health information over the telephone improves nurse satisfaction, feeling prepared to answer physician questions40 and preliminary evidence suggests that such interventions can also reduce adverse drug events and improve patient safety in the hospital setting.36

Although our study suggests that improving nurse preparedness is a key target to break the cycle of communication breakdown, our described communication model also illustrates the importance of improving physician attitudes, professionalism, and responsiveness. Interventions to improve the effectiveness of communication in the LTC setting must target both nurses and physicians to create a culture that facilitates effective communication with improved patient safety and healthcare quality as the ultimate goal.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Dr. Tjia was supported by a Mentored Clinical Scientist Career Development Award from the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG021527). This study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS016463).

References

- 1.The Joint Commission. National Patient Safety Goals - Long-term Care Program. [June 17, 2009];2008 [On-line] http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/08_ltc_npsgs.htm.

- 2.Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To err is human Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Joint Commission. Improving America's Hospitals: The Joint Commission's Annual Report on Quality and Safety. [June 17, 2009];2007 [On-line] http://www.jointcommissionreport.org/pdf/JC_2007_Annual_Report.pdf.

- 4.Parker J, Coiera E. Improving clinical communication: a view from psychology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:453–461. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson NS, Wald KS, Grenvik AN, et al. Adverse occurrences in intensive care units. JAMA. 1980;244:1582–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lingard L, Espin S, Whyte S, et al. Communication failures in the operating room: an observational classification of recurrent types and effects. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:330–334. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, et al. Interdisciplinary communication in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:347–352. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez G, Coiera E. Interdisciplinary communication: an uncharted source of medical error? J Crit Care. 2006;21:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayser-Jones JS, Wiener CL, Barbaccia JC. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 1989;29:502–510. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt IK, Svarstad BL. Nurse-physician communication and quality of drug use in Swedish nursing homes. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1767–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKnight L, Stetson PD, Bakken S, et al. Perceived information needs and communication difficulties of inpatient physicians and nurses. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9:S64–S69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazirani S, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on communication and collaboration among physicians and nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verschuren PJ, Masselink H. Role concepts and expectations of physicians and nurses in hospitals. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1135–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott PA, Bowen SA. Physician-nurse relationships. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:127–133. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cadogan MP, Franzi C, Osterweil D, et al. Barriers to effective communication in skilled nursing facilities: differences in perception between nurses and physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cadogan MP, Franzi C, Osterweil D. Utilization of standardized procedures in skilled nursing facilities: The California experience. Ann Long Term Care. 1998;6:130–139. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins A, Gagnon R, deGruy F. A comparison of after-hours telephone calls concerning ambulatory and nursing home patients. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kayser-Jones JS. Distributive justice and the treatment of acute illness in nursing homes. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNabney MK, Andersen RE, Bennett RG. Nursing documentation of telephone communication with physicians in community nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:180–185. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123027.01976.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fowkes W, Christenson D, McKay D. An analysis of the use of the telephone in the management of patients in skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:67–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker P. Common Pitfalls in Published Grounded Theory Research. Qual Health Res. 1993;3:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger R. Analyzing and Reporting Focus Group Results. London: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conzola V, Wogalter M. A Communication-Human Information Processing (C-HIP) approach to warning effectiveness in the workplace. J Risk Res. 2001;4:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arford PH. Nurse-physician communication: an organizational accountability. Nurs Econ. 2005;23:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Auger J, et al. Communicating safety information to physicians: an examination of dear doctor letters. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:869–875. doi: 10.1002/pds.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenstein AH, O'Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenstein AH, O'Daniel M. Disruptive behavior and clinical outcomes: perceptions of nurses and physicians. Am J Nurs. 2005;105:54–64. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMahan EM, Hoffman K, McGee GW. Physician-nurse relationships in clinical settings: a review and critique of the literature, 1966-1992. Med Care Rev. 1994;51:83–112. doi: 10.1177/107755879405100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller DB, Brimigion J, Keller D, et al. Nurse-physician communication in a nursing home setting. Gerontologist. 1972;12:225–229. doi: 10.1093/geront/12.3_part_1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmer JG, Watson NM. Physician response to notification of acute problems in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:348–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barenfanger J, Sautter RL, Lang DL, et al. Improving patient safety by repeating (read-back) telephone reports of critical information. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:801–803. doi: 10.1309/9DYM-6R0T-M830-U95Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koczmara C, Jelincic V, Perri D. Communication of medication orders by telephone--“writing it right”. Dynamics. 2006;17:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenfield LJ. Doctors and nurses: a troubled partnership. Ann Surg. 1999;230:279–288. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gittell JH, Fairfield KM, Bierbaum B, et al. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: a nine-hospital study of surgical patients. Med Care. 2000;38:807–819. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:956–959. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000056183.89175.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouslander J, Turner C, Delgado D, et al. Communication between primary physicians and staff of long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:490–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitson HE, Hastings SN, Lekan DA, et al. A quality improvement program to enhance after-hours telephone communication between nurses and physicians in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1080–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levenson S, Vance J, American Medical Directors Association . Protocols for Physician Notification: Assessing and Collecting Data on Nursing Home Facility Patients - A Guide for Nurses on Effective Communication with Physicians. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute for Health Improvement. SBAR Technique for Communication: A Situational Briefing Model. [June 17, 2009]; [On-line] http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/SafetyGeneral/Tools/SBARTechniqueforCommunicationASituationalBriefingModel.htm.

- 43.Manning ML. Improving clinical communication through structured conversation. Nurs Econ. 2006;24:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]