Abstract

Previous evidence established that a sequestered form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP pools) resides in the membrane/cytoskeletal complex of red cell porous ghosts. Here, we further characterize the roles these ATP pools can perform in the operation of the membrane's Na+ and Ca2+ pumps. The formation of the Na+- and Ca2+-dependent phosphointermediates of both types of pumps (ENa-P and ECa-P) that conventionally can be labeled with trace amounts of [γ-3P]ATP cannot occur when the pools contain unlabeled ATP, presumably because of dilution of the [γ-3P]ATP in the pool. Running the pumps forward with either Na+ or Ca2+ removes pool ATP and allows the normal formation of labeled ENa-P or ECa-P, indicating that both types of pumps can share the same pools of ATP. We also show that the halftime for loading the pools with bulk ATP is 10–15 minutes. We observed that when unlabeled “caged ATP” is entrapped in the membrane pools, it is inactive until nascent ATP is photoreleased, thereby blocking the labeled formation of ENa-P. We also demonstrate that ATP generated by the membrane-bound pyruvate kinase fills the membrane pools. Other results show that pool ATP alone, like bulk ATP, can promote the binding of ouabain to the membrane. In addition, we found that pool ATP alone functions together with bulk Na+ (without Mg2+) to release prebound ouabain. Curiously, ouabain was found to block bulk ATP from entering the pools. Finally, we show, with red cell inside-outside vesicles, that pool ATP alone supports the uptake of 45Ca by the Ca2+ pump, analogous to the Na+ pump uptake of 22Na in this circumstance. Although the membrane locus of the ATP pools within the membrane/cytoskeletal complex is unknown, it appears that pool ATP functions as the proximate energy source for the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps.

INTRODUCTION

The work reported here is primarily oriented to evaluating different functional roles of sequestered forms of ATP (ATP pools) that reside within the human red cell ghost membrane/cytoskeletal complex. This work extends our previous studies (Parker and Hoffman, 1967; Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) that not only established the concept of a membrane-compartmented ATP, but also suggested that these pools of ATP were preferentially used by the Na+ pump. We showed that the ATP pools could be loaded either by incubation with ATP itself or by running the membrane-bound phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) reaction forward (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977). Here, we now test whether ATP generated by the membrane-bound pyruvate kinase (PK) also fills the membrane pools with ATP. This work also shows that at least a portion of the membrane Ca2+ pumps use these same pools of membrane ATP (compare with Proverbio et al., 1988). Most of our work has been based on the relative formation of the Na+-dependent formation of the Na+ pump's phosphointermediate, ENa-P, in porous ghosts washed free of all bulk-loading media. This component was first characterized in red cell ghosts by Blostein (1968, 1970), in which the ENa-P was labeled with [γ-32P] ATP. We showed that when the membrane pools of ATP were loaded with nonradioactive ATP, the formation of labeled ENa-P was inhibited until the unlabeled ATP was removed from the membrane pools (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977). This, presumably, was due to the decrease in the specific activity of the [γ-32P] ATP upon its encountering a high concentration of unlabeled ATP in the membrane pool. In a complementary study, Mercer and Dunham (1981) showed that in inside-out vesicles (IOVs), prepared from human red cell ghosts, compartmented ATP drove the strophanthidin-sensitive uptake of 22Na+, given K+ on the inside of the vesicles. Importantly, they also showed in their IOVs that the pool-sequestered ATP was insensitive to the bulk additions of glucose plus hexokinase. We have shown that this is also the case in the porous ghost system used in this present work. IOVs were used in this work to see if 45Ca2+ uptake could also be driven by ATP contained solely in the membrane pools.

The human red cell Ca2+ pump was first described by Schatzmann (1966). The Ca2+-dependent formation of its phosphointermediate, ECa-P, was characterized by Knauf et al. (1974b), again using [γ-32P] ATP. As with the Na+ pump, the formation of ECa-P, as shown here, was inhibited when the pool had been filled with unlabeled ATP, but could be seen again once the pool ATP had been removed by running the Ca2+ pump forward.

Ouabain is known to be a specific inhibitor of the Na+ pump (Schatzmann, 1953). It has been shown that ouabain binding to the outside of the red cell membrane is promoted by inside ATP (Hoffman, 1969; Bodemann and Hoffman, 1976). In addition, Huang and Askari (1975) have demonstrated that the tightly bound ouabain to human red cell ghosts can be rapidly released by incubation with Na+ together with ATP, requiring the absence of Mg2+. Experiments evaluating these functions of pool ATP alone are presented below.

It should be noted that the presence of compartmented ATP has only been characterized in ghost membranes. We have previously summarized work that indirectly supports the idea that ATP pools could exist in the intact red cell, but further study is necessary to definitively establish their presence and their role in the transport of Na+ and Ca2+ (Hoffman, 1997).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of porous ghosts

Hemoglobin-free porous ghosts were prepared as described previously (Heinz and Hoffman, 1965; Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) and summarized as follows. Human blood obtained by approved procedure and consent from normal adults was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. After careful aspiration of the supernatant and buffy coat, the packed cells were transferred to a syringe and then rapidly injected into 20 vol of a stirred NaCl-Tris hemolysis/wash solution, whose composition was 15.3 mM NaCl and 1.7 mM Tris, which also contained 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, at 4°C. After 5 min and after 100% hemolysis had occurred, the suspension was centrifuged for 20 min at 20,000 g at 4°C. The ghosts were then washed four times with the same NaCl-Tris solution with EDTA at 15,000 g for 5 min, after which they appeared light pink to white. 1-ml aliquots of the packed ghosts were then frozen two to three times at −20°C. Before use, the thawed ghosts were washed three times with 20 vol of the same iced NaCl-Tris (pH 7.4 at 4°C) wash solution to free the ghosts of Na+ and EDTA. The resulting hemoglobin-free packed ghosts were then pelleted (protein concentration was ∼3.5 mg/ml) and used as described in the experiments below.

It is important to understand that the human red blood cell ghosts, having been frozen at −20°C and subsequently thawed and washed, were found to be permeable, hence porous, to all added constituents, such as ions, nucleotides, and the metabolic substrates used in the various treatments described below. In addition, these ghosts, while retaining other membrane-bound enzymes associated with glycolysis (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977; Campanella, et al., 2005) as well as the ATPases that represent the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps, were nominally free of adenylate kinase activity. This latter activity was tested by chromatographic analysis of ghosts exposed to ADP as well as by using the adenylate kinase inhibitor Ap5A (p1,p5-di[adenosine-5′) pentaphosphate (Lienhard and Secemski, 1973) in certain experiments related to those described below.

All of the experiments were performed three or four times with comparable results. The basic methods used were either those described by Proverbio and Hoffman (1977) or by more recent protocols, with the exception of the two types of experiments involving ouabain, which were modified to downscale the procedures that served not only to conserve resources, but also turned out to improve the accuracy of the various determinations. These later procedures are described below together with the protocols as used for the various types of experiments reported in Results.

It should be understood that each type of experiment involved pretreatment(s) of the porous ghosts, followed by washing before assaying the effect of the pretreatment(s) on the level of the phosphointermediate associated with either the ghost Na+ pump (ENa-P) or the ghost Ca2+ pump (ECa-P), and in some cases their respective ATPase activities. It is important to note that after each type of pretreatment, the ghosts were washed four to five times at 0°C, each with at least 10 vol of solution, to ensure that each treatment was a separate exposure with no carryover of the bulk phase constituents either within or outside the ghosts. The composition of the wash solution was 17 mM Tris Cl, pH 7.4.

Assay for ENa-P and ECa-P and their ATPase activities

The phosphointermediates were determined by use of the following protocol. In all instances, after any pretreatment the ghosts were packed before use. The procedures used were based on those previously described by Blostein (1968) and Proverbio and Hoffman (1977), in which all solutions and incubations were kept at 0°C. 40 µl of the [γ-32P]ATP labeling solution plus 10 µl of either NMDG or NaCl and/or CaCl2 was added to each Eppendorf tube for each time point (0 and 30 s). The final concentrations were 12 µM MgCl2, 2 µM Tris2 ATP, and 17 mM TrisCl, pH 7.4, at 0°C for the labeling solution plus 2 × 105 cpm [γ-32P]ATP. The [γ-32P]ATP was either made by us (see Glynn and Chappell, 1964) or purchased commercially. The final concentrations of either NMDG or NaCl were 50 mM and 50 µM for CaCl2. The labeling procedure was initiated by adding 50 µl of the packed ghosts with immediate mixing and incubating for 30 s to reach maximum formation of the phosphointermediates. The incubation was terminated by adding 500 µl of a stop solution that contained 5% TCA, 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM K2PO4. The precipitate was then washed with the stop solution at least three times before being dissolved in 500 µl of 1% Triton X-100 solution. Aliquots were counted in Optifluor. The protein concentration was determined by using standard Bio-Rad Laboratories reagents and procedures. After determining the specific activity of the labeling solution, the amount of each 32P-labeled phosphointermediate, i.e., ENa-P and ECa-P, could be quantitated.

The ATPase activities, except for the studies involving ouabain (see below), were determined in separate experiments by using the same protocol as above but with the incubation time extended to 20 min at 0°C. The amount of liberated 32P, i.e., orthophosphate, was determined by counting aliquots of the supernatant before and after treatment with activated charcoal (see Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977).

The Na+, K+-ATPase activities measured in the experiments involving ouabain were performed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min, as described by Knauf et al. (1974a), in the presence of 40 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris Cl (pH 7.4 at 37°C) together with [γ-32P]ATP. Analysis involved the determination of inorganic 32P liberated before and after exposure to activated charcoal. The determination of the bound [3H]ouabain content was performed as described by Bodemann and Hoffman (1976).

Presentation of the phosphointermediate and associated ATPase results

We have previously shown (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) and confirmed in the present work that in all conditions studied, the size of the phosphointermediate formed in the presence of Mg plus NMDG (EMg-P) was the same and invariant for each of the conditions in any one experiment. For instance, for all conditions in Experiment A of Fig. 1, the values for the Na-insensitive component ranged ±SEM, from 0.41 to 0.51 ± 0.04. This invariance in EMg-P was also documented in Proverbio and Hoffman (1977). Thus, for the purposes of clearer presentation, we have subtracted the Mg plus NMDG component from each of the results (except those in Fig. 7, D and E), such that only the Na+-sensitive or the Ca2+-sensitive (or in some cases the Na+ plus Ca2+-sensitive) component of the phosphointermediate is presented. This also applies to the measured associated ATPase activities. The bars in all the figures represent ±SEM, where n = 2–4 unless otherwise stated.

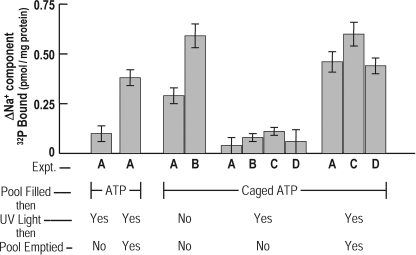

Figure 1.

ATP, photoreleased from pool-entrapped caged ATP, is a substrate for the Na+ pump. As described in Materials and methods, the protocol was modified by the substitution of caged ATP for Tris-ATP. All manipulations were performed in the dark, except for the exposure of some ghosts to ultraviolet light. Thus, porous ghosts were loaded at 37°C either with Tris-ATP (far left columns, A) or with caged ATP (columns A–D, above “Caged ATP”). All ghosts were put through two incubations, the first for filling the membrane pool with either Tris-ATP or caged ATP. After loading and washing, portions of the ghosts, where indicated, were irradiated with ultraviolet light for 15 min in the cold. The second incubation was used to empty the pool of ATP in portions of ghosts by running the Na+ pump forward, at 37°C, with Na+ plus K+ before determining in the dark the level of the Na-sensitive (i.e., the ΔNa+) components of the phosphointermediate, ENa-P. The results of four experiments (A–D) are shown. On the far left side, control ghosts (A) were filled with Tris-ATP and exposed to UV light, with the pool being emptied in one set before assay for ENa-P. It was found that the ΔNa+ component of ghosts harboring pool ATP is less than that of ghosts in which the pool has been emptied. Importantly, the same pattern is seen in the group of ghosts with entrapped caged ATP. Importantly, it is evident that the ΔNa+ component is low in ghosts containing photoreleased ATP (A, B, C, and D, middle group, above “YES-NO”) and high in those ghosts in which either ATP was not released (A and B, left columns, above “NO-NO”) or was removed (A, C, and D, far right columns, above “YES-YES”) by running the Na+ pump forward.

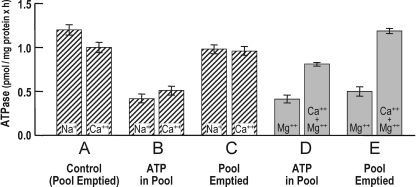

Figure 7.

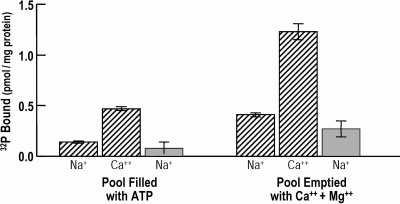

Both the Na+ pump– and Ca2+ pump–associated ATPase activities are modified, like their associated phosphointermediates, by pool ATP. The results of the two experiments (hatched and shaded bars) shown here parallel the conditions described in Fig. 6, except that the respective ATPase activities of the two types of pumps, rather than their phosphointermediates, were measured by the use of [γ-32P]ATP, as described in Materials and methods. It is evident that when ATP is in the pool, the Na+- and Ca2+-stimulated ATPase activities of the ghosts in B are reduced relative to their respective counterparts in A. In addition, when pool ATP is removed (by incubation with Na+ plus K+ as in Fig. 6) the ATPase activities of both types of pumps are stimulated (comparing B to C, and D to E), returning to essentially control levels. Note that in D and E the two conditions are represented by Mg2+ ± Ca2+. Similar results were obtained in two other experiments. The values are ±SEM, where n = 4.

Loading and emptying the membrane pool of ATP

The membrane pools of porous ghosts were loaded as described previously (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) by incubation for 30 min at 37°C in 5 vol of solution that contained 1–1.5 mM Tris ATP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris Cl, pH 7.5 at 37°C. The ghosts were then washed with 17 mM Tris Cl, pH 7.4, before use in the various experiments. The filled pool of ATP was unloaded either by further incubating the washed ghosts at 37°C in the presence of 40 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 10 mM Tris Cl (pH 7.5 at 37°C), or by substituting 50 µM CaCl2 for the NaCl plus KCl constituents.

For the experiments involving caged ATP (NPE-caged ATP: [Na2P3-(1-(2-nitrophenyl/ethyl) ester]), the protocol described above was modified as follows. 1 mM of caged ATP was substituted for Tris-ATP, and the solutions were placed in quartz vials and kept in the dark at 0–4°C. After the addition of porous ghosts, some vials were kept in the dark at 0–4°C for 45 min, whereas other vials were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 min and then returned to 0–4°C. Portions of the latter vials were then exposed to ultraviolet radiation (by use of a handheld lamp) with stirring for 15 min at 0–4°C. All ghosts were then transferred to Eppendorf tubes and washed by the usual procedure before a second incubation at 37°C, where, in portions of ghosts, the pool of control and released ATP was emptied by use of Na+ plus K+. Again, all incubations and washings together with the assay for the Na pump's phosphointermediate, ENa-P, were performed in the dark.

It is important to understand that the hallmark of whether or not the membrane pool contains ATP depends on whether or not the relevant phosphointermediates can be seen upon labeling with [γ-32P]ATP, as described above. ENa-P or ECa-P is not seen as long as unlabeled ATP is present in the membrane pool. Once ATP is removed, either ENa-P or ECa-P is in evidence.

IOVs

22Na+ and 45Ca uptakes were measured in IOVs according to the methods described by Mercer and Dunham (1981). In brief, after preparation, the IOVs were equilibrated overnight at 4°C in a medium (wash solution) that contained (in mM): 10 NMDG, 2 MgCl2, 0.25 EDTA, and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.3 at 23°C). The IOVs were then centrifuged and resuspended in the same composition solution ± 1.5 mM Tris ATP and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. This first incubation served to load ATP into the membrane pools of IOVs. Those IOVs incubated without ATP served as controls. The IOVs were washed four times at 0–4°C, with minimal, if any loss of ATP (see Proverbio and Hoffman 1977), and then incubated a second time for 15 min at 37°C in the original solution (without ATP) in the absence or presence of 8 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM KCl, and 1 µM valinomycin. This latter incubation with Na+ plus K+ served to run the Na+ pump forward, removing in IOVs the ATP from their previously filled pools, but not from ATP-free control ghosts. The IOVs were again washed four times at 0–4°C, again with minimal loss of ATP, with the original wash solution before final suspension in media in which the uptake of either 22Na or 45Ca was measured, as explained in the Table I legend. The 22Na and 45Ca uptakes were measured over a 2-min period at 23°C before being stopped by immediate filtering and washing with the original iced wash solution. The filters were then processed for counting and protein determinations. It should be noted that because the IOVs have resealed during their preparation, valinomycin is used to allow the penetration of K+ to the inside (i.e., the external surface of the pump) for activation of Na+/K+ exchange. Also, the cardiotonic aglycone strophanthidin was used to inhibit the pump because the IOVs are impermeable to ouabain.

TABLE I.

Pool ATP alone can drive the uptake of 45Ca++, like that of 22Na+, into IOVs made from human red blood cells

| Experiment | Pool condition incubation | ATP in pool | Medium assay condition | Uptake into IOVs | ||

| First | Second | 22Na+ | 45Ca++ | |||

| nmol/mg protein × min | ||||||

| A | Control (NMDG only) | Control (NMDG only) | No | Na+ + ATP | 14.4 ± 0.72 | — |

| Na+ + K+ + ATP | 21.4 ± 2.5 | |||||

| Na+ + K+ + ATP + Stroph. | 14.4 ± 2.0 | |||||

| B | ATP | NMDG | Yes | Na+ | 8.9 ± 0.5 | — |

| Na+ + K+ | 12.0 ± 0.3 | |||||

| Na+ + K+ + Stroph. | 7.9 ± 0.3 | |||||

| C | ATP | Na+ + K+ | No | Na+ | 9.1 ± 0.3 | — |

| Na+ + K+ | 8.0 ± 0.4 | |||||

| NMDG | Yes | Na+ | 9.6 ± 0.4 | |||

| Na+ + K+ | 17.4 ± 3.5 | |||||

| D | ATP | Na+ + K+ | No | Ca++ | — | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| NMDG | Yes | Ca++ | — | 7.1 ± 0.2 | ||

IOVs were prepared and the fluxes were performed as described in Materials and methods. The ATP pool of IOVs was manipulated as indicated in separate incubations. After the final washing, the fluxes were measured over a 2-min period at 25°C by suspending the IOVs in a solution that contained, when present, (in mM): 8.0 NaCl, 0.5 KCl, 1 µM valinomycin, 1 µM strophanthidin, and 2.5 glycylglycine, pH 7.4, ± 0.1 CaCl2. It is evident in experiments A, B, and C that the uptake of 22Na+ is stimulated when ATP is present in the pool together with K+. The pool-driven uptake of 22Na+ is also inhibited by the cardiotonic aglycone, strophanthidin. These results, as indicated in Results, are similar to those presented by Mercer and Dunham (1981). Importantly, as shown in experiment D, pool ATP alone stimulates the active transport of 45Ca++ across the plasma membrane. Values are ±SEM, where n = 3–4.

Material sources

All metabolic substrates were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) is the tri(cyclohexylammonium) salt of phospho(enol)pyruvic acid. All chemicals used were of reagent grade or of the highest purity available. The NPE-caged ATP was obtained from Invitrogen. [γ-32P]ATP, [3H]ouabain, Optifluor, and 22NaCl were purchased from PerkinElmer, and 45CaCl2 was from GE Healthcare.

RESULTS

Previous work (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) established by using porous ghosts that ATP can be entrapped within a membrane/cytoskeletal compartment (e.g., pool) that is preferentially used by the Na+ pump. Labeling the Na+ pump's phosphointermediate with trace amounts of bulk-added [γ-32P]ATP only occurs when the pool is empty of ATP. If the pool is prefilled with unlabeled ATP, the formation of the phosphointermediate is not seen until the pool's ATP is removed. Presumably, this is because the specific activity of the [γ-32P]ATP is markedly reduced when it mixes with pool ATP, so that significant labeling of the phosphointermediate cannot take place. Because the formation of the Na+ pump's phosphointermediate, ENa-P, is dependent on the presence of Na+, the measurement is performed (refer to Materials and methods) in the presence and absence of Na+, with the results expressed as the Na+-sensitive or ΔNa+ component of the 32P bound to the membranes.

The results presented in Fig. 1 show these basic characteristics. For instance, in the two columns labeled A on the far left side, the ghosts were either filled or emptied of pool ATP. It is evident that ENa-P reflects the pool's contents in that ENa-P is low in the former and high in the latter group of ghosts. But the important results shown in this figure are those in which the ghosts are filled with “caged ATP,” a protected and inactive form of ATP (Kaplan et al., 1978). The levels of ENa-P appear relatively unaffected until ATP, per se, is released by photolysis by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. The results of four different experiments (A, B, C, and D) are shown in Fig. 1. In each case, the formation of ENa-P is essentially unaffected with entrapped caged ATP (A and B, left, above “NO-NO”) but inhibited upon the release of nascent ATP in each of the groups (groups A, B, C, and D, middle, above “YES-YES”). Removing released ATP, by running the Na+ pump forward with Na+ plus K+, provides for the recovery of ENa-P to control levels (groups A, C, and D, right, above “YES-YES”). The results of the two left-hand columns, A, indicate that both the pool and Na+ pumps are unaffected by exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

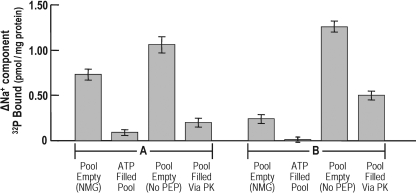

The metabolism of red blood cells is almost completely characterized by glycolysis in which glucose is converted to lactate. The only two enzymes in the glycolytic cycle that synthesize ATP are PGK and PK. Both of the enzymes have been found bound to the ghost membrane (Schrier, 1966). We have shown that the ATP that is generated by running the PGK reaction forward is another way by which the membrane pool can be loaded (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977). We therefore wanted to test if the PK reaction, i.e., ADP + PEP ⇌ ATP + pyruvate, could also deposit ATP in the membrane pool. The results presented in Fig. 2 show that this is the case. The results of two similar experiments (A and B) are shown. The first two columns of each set are controls in which the pool is either empty or filled by preincubation with ATP. The third column of each set shows that the pool is empty if PEP is left out of the reaction mixture. The important result, as shown in the fourth column of each set, is that the pool is filled with ATP when both substrates are present. It should be mentioned that because PK is known to be labile (Gutmann and Bernt, 1974), these results could only be seen by using fresh ghosts <4 h old. A serendipitous finding is that seen in the third column of each set where the ghosts were incubated in the presence of ADP alone. The fact that the pool remained empty is consistent with our previously mentioned finding that adenylate kinase activity is absent in these preparations of porous ghosts.

Figure 2.

ATP synthesized by membrane-bound PK can fill the membrane pool of porous ghosts. Because human red cell PK is known to be unstable, these experiments were completed in <4 h from the time of hemolysis to the use of the stop solution in the determination of the phosphointermediates. The synthesis of ATP by membrane-bound PK is performed by the reaction: ADP + PEP ⇌ ATP + pyruvate. Thus, washed porous ghosts were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in a solution that contained (in mM): 2 MgCl2, 70 KCl, 40 NMDG, and 10 Tris Cl (pH 7.3 at 37°C) together with 0.2 Tris-ADP and ± 2.0 PEP. Control ghosts in each set were also included and were prepared as usual by incubation with either NMDG or ATP. The ghosts were then washed at 0–4°C before being assayed for the determination of ENa-P. The results of two similar experiments are shown (A and B). The left two columns of each set show, as controls, the usual characteristics of the ΔNa+-sensitive component when the pool is either empty or loaded with ATP. The two right columns of each set show the important result that without PEP in the reaction mixture, the pool is empty in comparison to when the pool is filled with ATP that was synthesized by the full PK reaction. This is reflected in the relative levels, respectively, of the ΔNa+ component of these paired columns.

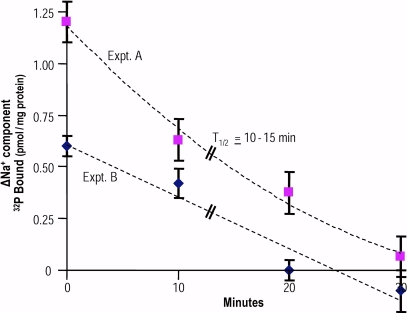

Fig. 3 shows the time course by which the membrane pool can fill with ATP. Here, porous ghosts are incubated in the standard way (refer to Materials and methods) in the presence of ATP. Two different protocols were used, as noted in the legend. The results show that in both cases, the halftime for filling is 10–15 min. The leakage rate of ATP from the membrane pool is much slower than the filling time because it takes some 90 min to empty the once-filled pool by incubation at 37°C in the presence of Mg2+ and choline (or NMDG); pool ATP can be depleted in ∼15 min by running the Na+ pump forward with Na+ plus K+ (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977).

Figure 3.

The time course of filling the membrane pool of porous ghosts with ATP. Ghosts were loaded with ATP according to the standard procedure described in Materials and methods. However, the protocols for the timed sequences of sampling were different for the two experiments shown. In A, ghosts were added to a large batch of loading medium and then sampled for the determination of ENa-P at time zero, 10, 20, and 30 min. Samples were processed according to the usual procedure after exposure to the stop solution. In B, four different sets of tubes were prepared to contain the ATP-loading medium with ghosts added at zero time and at 10-min intervals up to 30 min. All samples were then processed together for the determination of the ΔNa+ component. It is evident that halftime (T1/2) is 10–15 min, essentially the same for the two protocols.

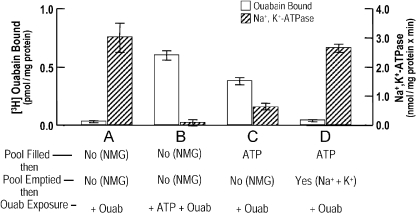

Figs. 4 and 5 show that pool ATP alone can function not only to promote ouabain binding to porous ghosts, but it also acts as a critical partner with Na+ to elute bound ouabain. It has long been known that bulk medium ATP acts to stimulate the binding of ouabain to porous (Hoffman, 1969) as well as to resealed (Bodemann and Hoffman, 1976) ghosts. Thus, it was of interest to test the role of pool ATP in this regard. Fig. 4 shows the extent to which ouabain binding and its resultant effects on Na+, K+-ATPase are dependent on pool ATP. Note the reciprocal relation between ouabain binding and its associated Na+, K+-ATPase activity. When ouabain is bound, the ATPase is inhibited and vice versa. In Fig. 4, columns A and B are controls showing that the presence of bulk ATP (B) supports ouabain binding, which does not occur in its absence (A). The main result is shown in C, where it is clear that the presence of pool ATP, per se, promotes the binding of ouabain to the ghosts, but not after the pool has been emptied of ATP (D).

Figure 4.

Pool ATP alone promotes the binding of ouabain to porous ghosts with inhibition of the Na+, K+-ATPase. Porous ghosts were incubated as described in Materials and methods either to leave the membrane pools empty (paired columns, A and B) or to fill them with ATP (C and D). In a second incubation, the pools of ATP in one set of ghosts (D) were removed by running the Na+ pump forward in the presence of Na+ plus K+. “No” and “Yes” refer to whether or not the pools are empty or filled. After the final preparative washing, each set of ghosts was incubated a third time for 30 min at 37°C in a solution that contained (in mM): 40 NaCl, 1.25 MgCl2, and 10 Tris Cl, PH 7.2 at 37°C. One set of ghosts was incubated with 1.5 mM Na2 ATP. In addition, all sets of ghosts were incubated with 10−7 M [3H]ouabain (specific activity, 2 mCi/mM) in the presence and absence of 10−4 M ouabain. Then, at the end of this incubation, the ghosts were washed and assayed for the content of bound ouabain (open bars, left ordinate) and their associated Na+, K+-ATPase activity (hatched bars, right ordinate) as described in Materials and methods. Specific binding was taken as the difference in the binding of 10−7 M [3H]ouabain with and without 10−4 M ouabain. Groups A and B represent controls showing that in the absence of ATP (A), ouabain was not bound and the Na+, K+-ATPase activity was uninhibited. However, when ATP was present in the bulk medium (B), ouabain was bound and the Na+, K+-ATPase was inhibited. The important finding shown in group C is that pool ATP alone supports ouabain binding together with the concomitant inhibition of the ATPase activity. Ouabain binding is not supported when the ATP in the pools has been removed (D), and the Na+, K+-ATPase activity is now unaffected as well. This is one of three experiments with similar results. Values shown are ±SEM, where n = 3.

Figure 5.

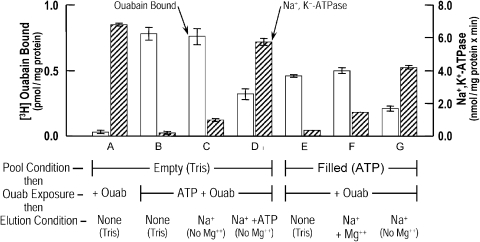

ATP alone entrapped in the membrane pool promotes the elution of ouabain bound to porous ghosts. This type of experiment was performed in an analogous fashion to those presented in Fig. 4. Here, in the first incubation, batches of ghosts were either left empty (groups A–D) or filled with ATP (E–G) as described in Materials and methods. The ghosts were then exposed, in a second incubation for 30 min at 37°C, to 10−7 M [3H]ouabain ± 10−4 M ouabain, as described in the legend to Fig. 4. This incubation was performed in the absence (A) or in the presence of bulk solution ATP (B–D). In addition, [3H]ouabain was also bound as before to washed ghosts containing only pool ATP (E–G). All ghosts (A–G) were washed and then incubated for 15 min at 37°C in either 40 mM Tris Cl (pH 7.2 at 37°C) for groups A, B, and E, in 30 mM NaCl plus 10 mM Tris Cl (in the absence of Mg2+) for groups C and G, or in 1.4 mM Na2 ATP plus 30 mM NaCl plus 10 mM Tris Cl for D. Group F was incubated in 2 mM MgCl2 plus 30 mM NaCl plus 10 mM Tris Cl. The ghosts were then washed and processed as before for determination of bound [3H]ouabain and Na+, K+ -ATPase activity. It is clear that only in the conditions in D and G is [3H]ouabain eluted from the membranes with concomitant stimulation of the Na+, K+ -ATPase. Thus, bound and inhibitory [3H]ouabain is eluted by the combination of Na+ plus ATP in the absence of Mg2+. The important point is that pool ATP alone can subserve this function similarly to that of bulk solution ATP. See Results for further discussion. This is one of two experiments with similar results, where the values represent ±SEM and n = 3.

Ouabain is known to bind with high affinity to intact human red blood cells and to remain bound when porous ghosts are made, indicating that the dissociation constant is low. Ingram (1970) found that ∼12% of the ouabain bound to cells is lost over a period of 2 h and is not affected by the presence of 30 mM K+ or 10−4 ouabain. Huang and Askari (1975) found that bound ouabain could be rapidly eluted by the incubation of ghosts in the absence of Mg2+ but in the required presence of bulk Na+ and ATP. Thus, it was of interest to test if pool ATP per se could function in this regard. Evidently, the combination of Na+ plus ATP by itself markedly reduces the affinity of bound ouabain to the Na+ pump. The results (in terms of bound ouabain and Na, K-ATPase activity as in Fig. 4) presented in Fig. 5 show that pool ATP alone acts in concert with Na+ to promote the rapid elution of bound ouabain. Columns A–D are controls, confirming Huang and Askari (1975), showing the circumstances in which the ouabain, bound to the ghosts by preincubation with bulk ATP (with subsequent washing), is eluted. The columns in D show that only with exposure to Na+ plus bulk ATP (without Mg2+) is the already bound ouabain released; incubation with NMDG ± Na+ (B and C) are without effect. Importantly, when the pool is already filled with ATP, the addition of Na+ alone results in the elution of bound ouabain (G), where incubation either in NMDG (E) or with Na+ plus Mg2+ (F) is without effect.

A surprising and unexpected result is shown in the columns in C compared with the columns in G. Note that in C, the ghosts were incubated with ATP plus ouabain. Although ATP has promoted the binding of ouabain in this situation, ouabain has evidently prevented ATP from entering the membrane pool. This is because if ATP had been in the pool after washing, the bound ouabain should have been released by incubation with Na+ alone, comparable to that shown in G. This is considered further in Discussion.

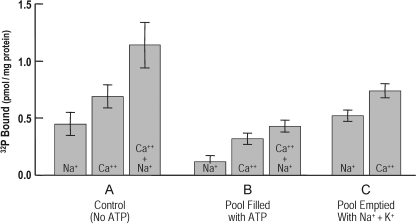

Fig. 6 presents results of experiments in which the Ca2+ pump's ECa-P parallels the behavior of the Na+ pump in response to the presence of pool ATP. The results in the columns of A show, consistent with previous results (see Knauf et al. 1974b), the levels of the phosphointermediates measured in the presence of Na+ or Ca2+, or both. Note that in the columns in B, these levels are inhibited when the pool contains ATP. Removal of pool ATP (C) results in the return to the control levels obtained in A. It should be noted that the two types of phosphointermediates tend to be additive. In addition, it is also evident that the levels of ECa-P are larger than those of ENa-P, consistent with there being more Ca2+ pumps than Na+ pumps (see Knauf et al. 1974b). This is considered further in Discussion.

Figure 6.

The Ca2+ pump like the Na+ pump can use pool ATP. Three groups of porous ghosts (A, B, and C) were prepared in which the size of the phosphointermediates ENa-P and ECa-P was measured. Group A represents the control group in which the ghosts were incubated as described in Materials and methods for 30 min at 37°C in the absence of ATP; group B ghost pools were filled with ATP by incubation for 30 min at 37°C in which a portion of the ghosts, group C, after washing, were emptied of their ATP by incubation for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of Na+ and K+. It is evident that the phosphoproteins measured in the presence and absence of either Na+ or Ca2+, or both, reflect the relative activities of their respective pumps indicated on the ordinate in terms of the levels of 32P bound for each condition. The results of similar determinations shown in group B indicate that the levels of both ENa-P and ECa-P are much reduced due to the ATP present in the pool. Removal of ATP (group C) results in a return to the control levels of each of the phosphointermediates. It should be noted, as discussed in Results, that ECa-P is larger than ENa-P, and that when the two are measured together they tend to be additive. Values are ±SEM, where n = 6.

Fig. 7 shows the results of two similar experiments (columns A, B, C, D, and E) in which the Ca2+ pump stimulated ATPase activity, like the Na+ pump (see also Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) uses pool ATP. The ATPase activity is high when the pool is empty (columns A, C, and E) compared with the inhibited activity (columns B and D) when the pool has been loaded with ATP, indicating the preference of the pumps for unlabeled ATP.

Fig. 8 shows that the ATP pool can be emptied by running the Ca+ pump forward, just like it was shown before that the pool can be emptied by running the Na+ pump forward by incubation with Na+ plus K+. The results of two different experiments are shown (hatched and plain bars). The group on the left shows the levels of ENa-P and ECa-P when the pool contains ATP. The group on the right indicates the recovery of each of the phosphointermediates after the pool has been emptied by the Ca2+ pump's ATPase activity. This result also indicates that the same membrane pools of ATP are used by both the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps.

Figure 8.

The Na+ and Ca2+ pumps use the same pool of ATP. In the results shown here, the pools of porous ghosts were filled with ATP, as described in Materials and methods. Whereas in the previously presented results the pool was emptied by incubation with Na+ plus K+ (and Mg2+), here the ghost pool of ATP was emptied by incubation (for 30 min at 37°C) in the presence of Ca2+ (and Mg2+) before assay for ENa-P and ECa-P. The solution used for this second incubation (the ghosts being filled with ATP in the first incubation) was (in mM): 0.05 CaCl2, 2.0 MgCl2, 40 NMDG, 0.2 EDTA, and 10 Tris Cl, pH 7.3 at 37°C. The results of two experiments (hatched and shaded bars) are shown. Comparison between their respective counterparts on the left-hand and right-hand sides indicates that both types of pumps share the same pool of ATP. Values are ±SEM, where n = 5.

The studies considered so far indirectly examine the effects of pool ATP on the relative activities of the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps through the lens of either their respective phosphointermediates or their ATPase activities. The results presented in Table I use IOVs to measure the membrane transport of both Na+ and Ca2+ as driven by either bulk medium ATP or, more importantly, pool ATP. Experiments A, B, and C present the results on the pump-mediated uptake (i.e., efflux) of Na+ in parallel and in magnitude to those previously reported by Mercer and Dunham (1981). The results in A show that bulk ATP, together with Na+ plus K+, stimulates Na+ uptake into vesicles, and this uptake is inhibited by strophanthidin. Experiments B and C show similar results with the important difference that the energy for the Na+-mediated uptake is provided by pool ATP alone. The important new finding is shown in D, where it is evident that, like Na+ uptake, Ca2+ uptake is driven by pool ATP alone.

Previous estimates in both porous ghosts and IOVs of the numbers of ATP molecules in each pool, assuming one pool per Na+ pump, lies between 100 and 700 (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977; Mercer and Dunham, 1981). Even so, the amount of [3H]ATP released from the preloaded pools in porous ghosts falls far short (see Table XI in Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977) of the estimated ATP concentration that supports the 22Na fluxes in IOVs as reported by Mercer and Dunham (1981). Obviously, there is sufficient ATP in both systems to influence pump-related activity, but new measurements will be necessary to quantitatively define the ATP concentration in pool size in both types of preparations.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding presented here is that ATP entrapped within the membrane/cytoskeletal complex functions as a proximal substrate for both the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps. This was shown by the use of ATP and its caged form (Fig. 1), where manipulation of the pool contents coincided with the labeling of the Na+ pump's phosphointermediate. We also showed that pool ATP in IOVs supports the pumped efflux of Na+ and Ca2+ (Table I). It should be understood that the results with IOVs are qualitative in showing that transport of Na+ and Ca2+ are supported by pool ATP, complimenting the results obtained by measuring ENa-P and ECa-P. Quantitation of relative pool activities is precluded because of the differences in ghost versus IOV preparations. It was further found (Fig. 2) that the membrane pool of ATP could be filled by running the pyruvic kinase reaction forward. In addition, it was demonstrated that the binding of ouabain to and its release from ghost membranes could be controlled by pool ATP alone (Figs. 4 and 5). Finally, as characterized in Figs. 6 and 7, it is evident that the same pool of ATP is used by membrane-bound Ca2+ and Na+ pumps (Fig. 8).

This latter point raises an interesting question about the relation of the number of Ca2+ pumps to Na+ pumps. The number of Na+ pumps/single human red cell is ∼400, estimated from the values of ouabain-binding sites or from values of ENa-P (see Joiner and Lauf, 1978). In contrast, estimates of the number of Ca2+ pumps ranges from ∼1,000, based on ECa-P levels in the absence of La+++ (Knauf et al., 1974b), to between 4,100 and 4,500 based on the number of calmodulin-binding sites (Jarrett and Kyte, 1979; Graf et al., 1980). A further complication is that red cell membranes contain two isoforms (types 1 and 4) of the Ca2+ pump, with type 4 being the predominant one (Strehler et al., 1990). The membrane locus of either type is not known. Nevertheless, it would seem likely that the membrane pool of ATP is used by all of the Na+ pumps but only a portion of the Ca2+ pumps. It should be noted that a form of compartmented ATP, glycolytically produced, has been shown to be used by the Ca2+ pump in smooth muscle plasma membrane vesicles (Hardin et al., 1992), but whether the form of this sequestered ATP is analogous to that in the red cell membrane has yet to be determined.

It was mentioned before that ATP promotes the binding of ouabain to porous ghosts. But, as noted in connection with Fig. 5, ATP was prevented from entering the pool when ghosts were incubated with ATP and ouabain together. We have seen this action of ouabain before under a different experimental protocol (Proverbio and Hoffman, 1977). We have no explanation for this effect, although future experiments should test that the formation of ENa-P was unaffected in this circumstance. Other cross-membrane effects on the Na+ pump are also known (see Hoffman, 2004). For instance, Eisner and Richards (1981) showed that there were reciprocal effects on the affinities of outside K+ and internal ATP. Regardless of this and other types of cross-membrane effects, there does not appear to be, as yet, any molecular insight into ouabain's effect on ATP pool loading, stemming from the known structural analyses of the Na+ pump (see Morth et al., 2009). Obviously, it will be instructive to know the location of these pools and their relation to the Na+ pump, as well as the identity of the cytoskeletal components that provide the corrals for the entrapped ATP. Preliminary evidence (unpublished data) implicate that the pools, determined by using both chemical and immunological means, in porous ghosts, are associated with the junctional (4.1) complex containing adducin, 4.1, and spectrin, rather than the ankyrin complex of the red cell cytoskeleton (see Salomao, et al., 2008 and Anong, et al., 2009). This indicates that the ATP pools exist separately from the ensembles of glycolytic enzymes (metabolons) that bind to the N terminus of the red cell Band 3 protein (Campanella et al., 2005, 2008). The junctional complex appears to be present in IOVs (see Mercer and Dunham 1981), even though the spectrin contents are markedly reduced. Quantitative comparison of pool constituents in the corrals of IOVs and porous ghosts should provide insight into pool function. But it is not clear as yet what the location is of the membrane-bound forms of PGK and PK. This is important because it is only these two enzymes that not only generate ATP within the mature red blood cell, but also supply the substrate to the Na+ and Ca2+ pumps via the pools.

Red blood cells are not the only cell types that indicate that certain physiological functions show a dependence upon ATP compartmentation. Thus, ATP that is produced via aerobic glycolysis in contrast to ATP produced by oxidative processes has been shown, for instance, to stimulate the Na+ pump in vascular smooth muscle (Lynch and Paul, 1987: Campbell and Paul, 1992), in brain (Lipton and Robacker, 1983), in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells (Balaban and Bader, 1984), in MDCK cells (Lynch and Balaban, 1987), in cardiac myocytes (Weiss and Lamp, 1987), and in astrocytes (Pellerin and Magistretti, 1994). It should be understood that the types of structures/compartmentation that underlie these separate sources of ATP production are at present unknown as well as their relationship to the type of ATP pools that have been characterized in red blood cells. Evidence for the presence of possible ATP compartmentation and glycolytic metabolons that effect membrane transport processes in a variety of other cell types has been reviewed by Dhar-Chowdhury et al. (2007) and by Saks et al. (2008).

Acknowledgments

The skilled technical assistance of Teresa Proverbio is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL 09906 and HL52750.

Paul J. De Weer served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- IOV

- inside-out vesicle

- PEP

- phosphoenolpyruvate

- PGK

- phosphoglycerate kinase

- PK

- pyruvate kinase

References

- Anong W.A., Franco T., Chu H., Weis T.L., Devlin E.E., Bodine D.M., An X., Mohandas N., Low P.S. 2009. Adducin forms a bridge between the erythrocyte membrane and its cytoskeleton and regulates membrane cohesion.Blood. 114:1904–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban R.S., Bader J.P. 1984. Studies on the relationship between glycolysis and (Na+ + K+)-ATPase in cultured cells.Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 804:419–426 doi:10.1016/0167-4889(84)90069-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blostein R. 1968. Relationships between erythrocyte membrane phosphorylation and adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis.J. Biol. Chem. 243:1957–1965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blostein R. 1970. Sodium-activated adenosine triphosphatase activity of the erythrocyte membrane.J. Biol. Chem. 245:270–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemann H.H., Hoffman J.F. 1976. Side-dependent effects of internal versus external Na and K on ouabain binding to reconstituted human red blood cell ghosts.J. Gen. Physiol. 67:497–525 doi:10.1085/jgp.67.5.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella M.E., Chu H., Low P.S. 2005. Assembly and regulation of a glycolytic enzyme complex on the human erythrocyte membrane.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:2402–2407 doi:10.1073/pnas.0409741102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella M.E., Chu H., Wandersee N.J., Peters L.L., Mohandas N., Gilligan D.M., Low P.S. 2008. Characterization of glycolytic enzyme interactions with murine erythrocyte membranes in wild-type and membrane protein knockout mice.Blood. 112:3900–3906 doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-146159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.D., Paul R.J. 1992. The nature of fuel provision for the Na+,K(+)-ATPase in porcine vascular smooth muscle.J. Physiol. 447:67–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar-Chowdhury P., Malester B., Rajacic P., Coetzee W.A. 2007. The regulation of ion channels and transporters by glycolytically derived ATP.Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64:3069–3083 doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7332-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner D.A., Richards D.E. 1981. The interaction of potassium ions and ATP on the sodium pump of resealed red cell ghosts.J. Physiol. 319:403–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn I.M., Chappell J.B. 1964. A simple method for the preparation of 32-P-labelled adenosine triphosphate of high specific activity.Biochem. J. 90:147–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E., Filoteo A.G., Penniston J.T. 1980. Preparation of 125I-calmodulin with retention of full biological activity: its binding to human erythrocyte ghosts.Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 203:719–726 doi:10.1016/0003-9861(80)90231-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann I., Bernt E. 1974. Pyruvate kinase: assay in serum and erythrocytes. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Bergmeyer H.U., editor Academic Press, New York: 774–778 [Google Scholar]

- Hardin C.D., Raeymaekers L., Paul R.J. 1992. Comparison of endogenous and exogenous sources of ATP in fueling Ca2+ uptake in smooth muscle plasma membrane vesicles.J. Gen. Physiol. 99:21–40 doi:10.1085/jgp.99.1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz E., Hoffman J.F. 1965. Phosphate incorporation of Na,K-ATPase activity in human red blood cell ghosts.J. Cell. Physiol. 65:31–43 doi:10.1002/jcp.1030650106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J.F. 1969. The interaction between tritiated ouabain and the Na-K pump in red blood cells.J. Gen. Physiol. 54:343–353 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J.F. 1997. ATP compartmentation in human erythrocytes.Curr. Opin. Hematol. 4:112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J.F. 2004. Some red blood cell phenomena for the curious.Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 32:335–340 doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W-H., Askari A. 1975. Red cell Na+,K+-ATPase: a method for estimating the extent of inhibition of an enzyme sample containing an unknown amount of bound cardiac glycoside.Life Sci. 16:1253–1261 doi:10.1016/0024-3205(75)90310-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram C.J. 1970. The binding of ouabain to human red cells. PhD thesis. Yale University, New Haven, CT: 105 pp [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett H.W., Kyte J. 1979. Human erythrocyte calmodulin. Further chemical characterization and the site of its interaction with the membrane.J. Biol. Chem. 254:8237–8244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner C.H., Lauf P.K. 1978. The correlation between ouabain binding and potassium pump inhibition in human and sheep erythrocytes.J. Physiol. 283:155–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J.H., Forbush B., III, Hoffman J.F. 1978. Rapid photolytic release of adenosine 5′-triphosphate from a protected analogue: utilization by the Na:K pump of human red blood cell ghosts.Biochemistry. 17:1929–1935 doi:10.1021/bi00603a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauf P.A., Proverbio F., Hoffman J.F. 1974a. Chemical characterization and pronase susceptibility of the Na:K pump-associated phosphoprotein of human red blood cells.J. Gen. Physiol. 63:305–323 doi:10.1085/jgp.63.3.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauf P.A., Proverbio F., Hoffman J.F. 1974b. Electrophoretic separation of different phophosproteins associated with Ca-ATPase and Na, K-ATPase in human red cell ghosts.J. Gen. Physiol. 63:324–336 doi:10.1085/jgp.63.3.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard G.E., Secemski I.I. 1973. P 1, P 5 -Di(adenosine-5′)pentaphosphate, a potent multisubstrate inhibitor of adenylate kinase.J. Biol. Chem. 248:1121–1123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P., Robacker K. 1983. Glycolysis and brain function: [K+]o stimulation of protein synthesis and K+ uptake require glycolysis.Fed. Proc. 42:2875–2880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch R.M., Balaban R.S. 1987. Coupling of aerobic glycolysis and Na+-K+-ATPase in renal cell line MDCK.Am. J. Physiol. 253:C269–C276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch R.M., Paul R.J. 1987. Compartmentation of carbohydrate metabolism in vascular smooth muscle.Am. J. Physiol. 252:C328–C334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer R.W., Dunham P.B. 1981. Membrane-bound ATP fuels the Na/K pump. Studies on membrane-bound glycolytic enzymes on inside-out vesicles from human red cell membranes.J. Gen. Physiol. 78:547–568 doi:10.1085/jgp.78.5.547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morth J.P., Poulsen H., Toustrup-Jensen M.S., Schack V.R., Egebjerg J., Andersen J.P., Vilsen B., Nissen P. 2009. The structure of the Na+,K+-ATPase and mapping of isoform differences and disease-related mutations.Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364:217–227 doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J.C., Hoffman J.F. 1967. The role of membrane phosphoglycerate kinase in the control of glycolytic rate by active cation transport in human red blood cells.J. Gen. Physiol. 50:893–916 doi:10.1085/jgp.50.4.893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L., Magistretti P.J. 1994. Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:10625–10629 doi:10.1073/pnas.91.22.10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio F., Hoffman J.F. 1977. Membrane compartmentalized ATP and its preferential use by the Na,K-ATPase of human red cell ghosts.J. Gen. Physiol. 69:605–632 doi:10.1085/jgp.69.5.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio F., Shoemaker D.G., Hoffman J.F. 1988. Functional consequences of the membrane pool of ATP associated with the human red blood cell Na/K pump. The Na+, K+-Pump, Part A: Molecular Aspects. Skou J.C., NØrby J.G., Maunsbach A.B., Esmann M., Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York: 561–567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks V., Beraud N., Wallimann T. 2008. Metabolic compartmentation - a system level property of muscle cells: real problems of diffusion in living cells.Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9:751–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomao M., Zhang X., Yang Y., Lee S., Hartwig J.H., Chasis J.A., Mohandas N., An X. 2008. Protein 4.1R-dependent multiprotein complex: new insights into the structural organization of the red blood cell membrane.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:8026–8031 doi:10.1073/pnas.0803225105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzmann H.-J. 1953. Herzglykoside als hemmstoffe für den aktiven kalium- und natriumtransport durch die erythrocytenmembran.Helv. Physiol. Pharmacol. Acta. 11:346–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzmann H.-J. 1966. ATP-dependent Ca++-extrusion from human red cells.Experientia. 22:364–365 doi:10.1007/BF01901136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier S.L. 1966. Organization of enzymes in human erythrocyte membranes.Am. J. Physiol. 210:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler E.E., James P., Fischer R., Heim R., Vorherr T., Filoteo A.G., Penniston J.T., Carafoli E. 1990. Peptide sequence analysis and molecular cloning reveal two calcium pump isoforms in the human erythrocyte membrane.J. Biol. Chem. 265:2835–2842 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J.N., Lamp S.T. 1987. Glycolysis preferentially inhibits ATP-sensitive K+ channels in isolated guinea pig cardiac myocytes.Science. 238:67–69 doi:10.1126/science.2443972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]