Abstract

Objective

To identify how different degrees of cholesterol synthesis inhibition affect human hepatic cholesterol metabolism.

Methods and Results

37 normocholesterolemic gallstone patients randomized to treatment with placebo, 20 mg/d fluvastatin or 80 mg/d atorvastatin for 4 weeks were studied. Based on serum lathosterol determinations, cholesterol synthesis was reduced by 42% and 70% in the two groups receiving statins. VLDL cholesterol was reduced by 20% and 55%. During gallstone surgery, a liver biopsy was obtained and hepatic protein and mRNA expression of rate-limiting steps in cholesterol metabolism were assayed and related to serum lipoproteins. A marked induction of LDL receptors and HMG CoA reductase was positively related to the degree of cholesterol synthesis inhibition (ChSI). The activity, protein and mRNA for ACAT2 were all reduced during ChSI, as was apoE mRNA. The lowering of HDL cholesterol in response to high ChSI could not be explained by altered expression of the HDL receptor CLA-1, ABCA1 or apoA-I.

Conclusions

Statin treatment reduces ACAT2 activity in human liver and this effect, in combination with a reduced Apo E expression, may contribute to the favourable lowering of VLDL cholesterol seen in addition to the LDL lowering during statin treatment.

Keywords: cholesterol, lipoprotein, liver, receptors, apolipoproteins

Introduction

Lipid-lowering therapy by inhibition of the activity of hydroxyl-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis, represents a major breakthrough in modern medicine. With cholesterol synthesis inhibition (ChSI), plasma levels of atherogenic LDL particles can be substantially reduced resulting in lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality both in patients with and without manifest disease1. The lipid-lowering effects of this class of drugs (statins) are generally ascribed to the compensatory increase in hepatic LDL receptor expression resulting from the activation of the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP-2) which occurs in response to reduced cholesterol availability in the liver following ChSI 2. At higher degrees of HMG CoA reductase inhibition, the concentrations of VLDL cholesterol and triglycerides are reduced, whereas HDL cholesterol levels may tend to be higher, unchanged or somewhat lowered depending on the statin that is given 3, 4. The mechanism(s) behind the latter changes are less well characterized, and their relationship to the more positive clinical effects of high-dose ChSI on cardiovascular disease has been debated 5.

We have recently demonstrated the presence of a specific enzyme catalyzing the esterification of cholesterol in human hepatocytes: acyl-Coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase 2 (ACAT2)6. On the basis of animal studies (for review see 7), we have postulated that this enzyme – in contrast to ACAT1 which is the major cholesterol esterifying enzyme in cells other than hepatocytes and enterocytes – is involved in the secretion of cholesteryl esters in VLDL from the liver. In order to further characterize the function of ACAT2, we have now performed a detailed study of the changes in hepatic cholesterol metabolism induced by low and high degrees of ChSI in human liver using a randomised, placebo-controlled design. Our studies demonstrate that ChSI by statins resulted in increasing induction of HMG CoA reductase and LDL receptors and a parallel reduction of ACAT2 and apo E expression. These changes occurred together with reduced plasma levels of VLDL and LDL cholesterol. The slight lowering of HDL seen in patients receiving atorvastatin 80 mg/day could not be correlated to changes in hepatic HDL receptors CLA-I or ABCA1 expression, but was proportional to the degree of VLDL lowering. Finally, ChSI resulted in reduced biliary cholesterol levels, further indicating a decreased turnover of hepatic cholesterol during statin therapy.

Methods

Please see supplemental methods (available online at http://atvb.ahajournals.org) for details on patients and operative procedure, chemical analysis of plasma and bile, for ligand blot and Western blot, for enzymatic ACAT activity, and for determination of mRNA expression.

Patients and treatments

Fertile female, post-menopausal female, and male patients (altogether 42), scheduled for elective cholecystectomy because of uncomplicated gallstone disease, were enrolled in the study. Five patients did not complete the study because of low compliance and thus 12 males, 12 fertile females, and 13 post-menopausal females were evaluated (Table 1). Each of the 3 patient groups was randomized to three treatment arms: placebo, fluvastatin 20 mg/day (Low-ChSI) or atorvastatin 80 mg/day (High-ChSI) for 4 weeks prior to surgery. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to inclusion into the study, which was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Karolinska Institutet and by the Swedish Medical Product Agency.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics and plasma lipid levels

| Placebo | Low ChSI | High ChSI | Placebo | Low ChSI | High ChSI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/FF/PF) | 4/4/4 | 4/4/4 | 4/4/5 | |||||

| Age | 50.6 ± 3.9 | 48.7 ± 3.9 | 54.3 ± 4.1 | NS | ||||

| BMI | 26.8 ± 1.3 | 29.5 ± 1.6 | 26.7 ± 1.1 | NS | ||||

| Before Treatment | After Treatment | |||||||

| Plasma total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.38 ± 0.46 | 5.37 ± 0.35 | 5.75 ± 0.33 | NS | 5.30 ± 0.44 | 4.38 ± 0.31 | 3.13 ± 0.18 | p < 0.001 |

| Plasma triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.41 ± 0.24 | 1.48 ± 0.14 | 1.23 ± 0.14 | NS | 1.29 ± 0.22 | 1.51 ± 0.33 | 0.94 ± 0.13 | NS |

| VLDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.80 ± 0.14 | 0.95 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | NS | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | p < 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.69 ± 0.29 | 2.79 ± 0.24 | 3.05 ± 0.21 | NS | 2.61 ± 0.30 | 2.12 ± 0.18 | 1.22 ± 0.10 | p < 0.01 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.89 ± 0.09 | 1.63 ± 0.09 | 1.90 ± 0.10 | NS | 1.86 ± 0.10 | 1.51 ± 0.10 | 1.54 ± 0.10 | NS |

| Apolipoprotein B (g/L) | 1.07 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.08 | 1.17 ± 0.12 | NS | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | p < 0.001 |

| Apolipoprotein AI (g/L) | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.27 ± 0.08 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | NS | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.22 ± 0.07 | 1.34 ± 0.10 | NS |

| Lathosterol/cholesterol (μg/mg) | 1.02 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.12 | NS | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | p < 0.001 |

M: male; FF: fertile female; PF: post menopausal female. Data show mean ± SEM. NS: not significant, ANOVA.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups wer tested by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc comparisons according to the LSD or the Dunnett methods (Statistica software, Stat Soft, Tulsa OK). Correlations were calculated with the Spearman rank order test.

Results

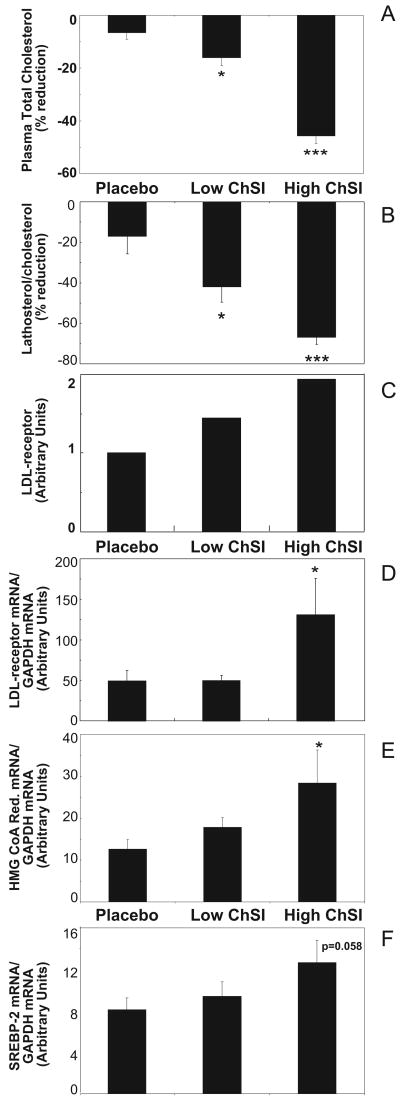

The goal of the study was to elucidate the molecular effects of varying degrees of ChSI on hepatic cholesterol metabolism in non-obese gallstone patients, randomized to treatment with placebo (Placebo), fluvastatin 20 mg/day (Low-ChSI), or atorvastatin 80 mg/day (High-ChSI) (Table 1). Plasma total cholesterol and the lathosterol/cholesterol ratio, an indirect measurement of whole body cholesterol synthesis, were determined in order to verify that different degrees of ChSI were reached. A tendency to a reduction in total cholesterol was observed with Placebo (Figure 1A), whereas Low-ChSI and High-ChSI resulted in 18% (p<0.05) and 44% (p<0.001) reductions, respectively. Similarly, a non-significant reduction in the lathosterol/cholesterol ratio was observed with Placebo (Figure 1B), whereas Low-ChSI and High-ChSI induced significant reductions of 42% (p<0.05) and 70% (p<0.001), respectively. Hence, three different levels of cholesterol synthesis were clearly apparent after treatment in the three experimental groups.

Figure 1.

Effects of ChSI on hepatic cholesterol metabolism. Percent reduction from baseline levels (see Table 1) in plasma total cholesterol (A) and in plasma lathosterol/cholesterol ratio (B); LDL receptor activity (C); LDL receptor mRNA (D); HMG CoA reductase mRNA (E); and SREBP-2 mRNA (F). Data show mean + SEM. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001. For details please see www.ahajornals.org

Analysis of LDL receptor protein expression in pooled hepatic membranes showed an increase which was inversely related to the degree of ChSI (Figure 1C). Measurement of the LDL receptor gene expression showed a significant (2.7-fold) induction of the mRNA levels only in the High-ChSI group (p<0.005; Figure 1 D). To further verify the expected transcriptional effects induced by the treatments, hepatic mRNA levels of HMG CoA reductase were determined. Corresponding to the LDL receptor changes, HMG CoA reductase mRNA was induced in the High-ChSI group (p<0.05; Figure 1E) whereas no significant change was observed in the Low-ChSI group. Accordingly, the expression of SREBP-2 mRNA showed a trend towards an increase that was related to ChSI (Figure 1F). Similar results were also observed for proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin (PCSK)-9, the expression of which showed a non-significant increase related to the degree of ChSI (Supplementary Table II).

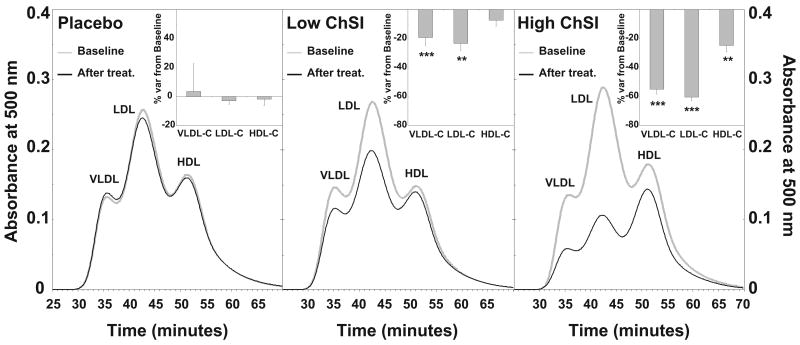

Separation of plasma lipoproteins by size exclusion chromatography demonstrated a reduction in the LDL cholesterol concentration that was inversely related to the degree of LDL receptor induction (Figure 2). Low-ChSI and High-ChSI showed 23% (p<0.01) and 60% (p<0.001) reductions in plasma LDL-cholesterol from baseline, respectively. Similarly, the magnitude of VLDL cholesterol reduction was related to the degree of ChSI (Figure 2). VLDL cholesterol was reduced by 19% in the Low-ChSI (p< 0.001) and by 55% (p< 0.001) in the High-ChSI group. A significant decrease in HDL cholesterol (-25%; p< 0.01) was also observed in the High-ChSI group.

Figure 2.

Effects of ChSI on plasma lipoprotein cholesterol profiles. Gray solid line, lipoprotein cholesterol profiles before treatment; black solid line, cholesterol lipoprotein profiles after treatment. Insets show % variation from baseline levels of the area-under-the-curve for each lipoprotein fraction. Data show mean ± SEM. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. For details please see www.ahajornals.org

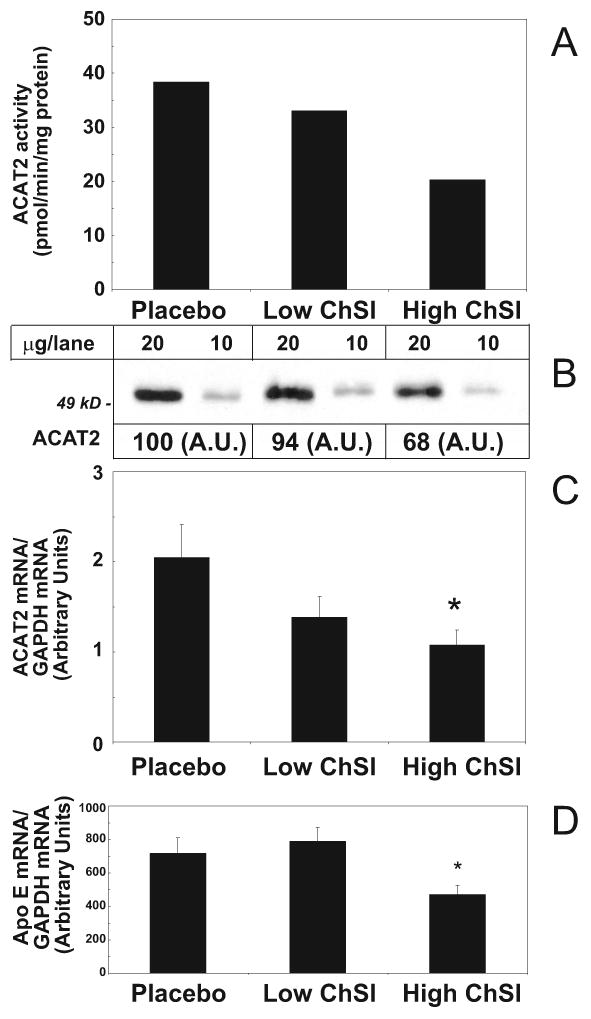

Another major aim of our study was to characterize the hepatic activity and gene expression of the cholesteryl ester-forming enzymes, ACAT2 and ACAT1. When compared to the controls, patients in the high-ChSI group had a 50% reduction in microsomal ACAT2 activity, while those in the Low-ChSI group only had a minor decrease (Figure 3A). The decrease in ACAT2 activity in the High-ChSI group was paralleled by a decrease in ACAT2 protein expression (Figure 3B). Measurements of ACAT2 mRNA levels also showed a significant decrease (Figure 3C). No effects were observed for the microsomal activity or for the mRNA expression of ACAT1 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of ChSI on hepatic ACAT2 and Apo E expression. A) ACAT2 activity in pooled liver microsomes; B) ACAT2 protein expression in pooled liver microsomes.; C) hepatic ACAT2 mRNA levels in individual mRNA preparations; D) apo E mRNA in individual mRNA preparations. Data show mean + SEM when individual samples were assayed. *, p<0.05. For details please see www.ahajornals.org

Analysis of the gene expression of the apolipoproteins involved in VLDL secretion revealed a significant decrease in apo E mRNA in the High ChSI group (-34%; p<0.05; Figure 3D), whereas no effects on apo B mRNA abundance were observed upon ChSI (Supplementary Table II). We also determined the apo B and apo E content in the VLDL before and during the different treatments. Interestingly, similar decreases (∼ 30%) in apo B and apo E were observed both in Low-ChSI and High-ChSI groups. No effects on the mRNA expression of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) were observed in response to ChSI (Supplementary Table II).

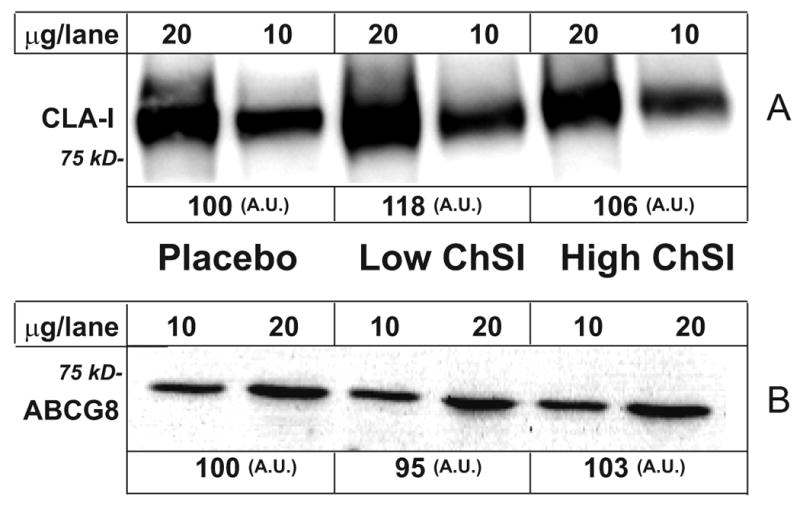

As mentioned above, HDL cholesterol levels were slightly reduced by High-ChSI treatment. This was independent of changes in apo A-I (% difference from baseline; Control, 0.70 ± 2.81; Low-ChSI, 21.6 ± 12.2; High-ChSI, 3.74 ± 6.94). Since animal experiments indicate that the hepatic expression of the HDL receptors, scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), may partly regulate plasma HDL cholesterol levels 9, we measured the protein expression of its human counterpart, CLA-I. Unexpectedly, Western blot analysis did not show any change of this protein in response to ChSI (Figure 4A), nor was there any change in its mRNA levels (Supplementary Table II). Other hepatic factors involved in the formation of plasma HDL, such as apo A-I, ABCA1, and CETP were not influenced by ChSI, at least not at the mRNA level (Supplementary Table II).

Figure 4.

Effects of ChSI on hepatic CLA-I and ABCG8 protein expression. Liver membrane proteins were loaded and separated on SDS/PAGE. After transfer onto nitrocellulose filter, samples were incubated with either A) anti-mouse SR-BI, reactive to human CLA-I, or B) with anti-human ABCG8 antibody. Data show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05. For details please see www.ahajornals.org

Finally, we assessed the effect of ChSI on biliary lipid composition in gallbladder bile after an overnight fast. The absolute concentrations of all biliary lipids (cholesterol, bile acids and phospholipids) were reduced by High-ChSI treatment (Table 2). This was associated with a reduction of the relative proportion of cholesterol (-40%; p< 0.05), resulting in a decreased saturation of gallbladder bile with cholesterol (-38%; p< 0.05). The mRNA expression of the biliary export pumps for cholesterol, ABCG5 and ABCG8, were not influenced by ChSI treatment (Supplementary Table II); neither was the protein expression of ABCG8 (Fig. 4B). No effect of ChSI was seen on the composition of individual bile acids or on bile acid production assayed by measurement of the plasma levels of C4/cholesterol (Supplementary Table II). The plasma plant sterols, campesterol and sitosterol, were increased during High-ChSI treatment (Table 3). Since the plant sterol/cholesterol ratio generally reflects intestinal absorption, this might be taken as an indication of increased absorption of dietary cholesterol 10. However, since the change in plant sterol ratios was inversely correlated to molar % cholesterol in bile (R= -0.44 for campesterol and R=-0.40 for sitosterol, respectively; both p< 0.05), it may be more plausible to ascribe this relative change as reflection of the reduced secretion of biliary cholesterol.

Table 2.

Bile composition and plasma 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) and plant sterols.

| Placebo | Low ChSI | High ChSI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biliary cholesterol (mmol/L) | 13 ± 1.7 | 15 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 1.2* |

| Biliary bile acids (mmol/L) | 101 ± 19 | 83 ± 13 | 51 ± 17* |

| Biliary phospholipids (mmol/L) | 34 ± 5.0 | 34 ± 4.2 | 21 ± 6.2* |

| Cholesterol % molar | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 12 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 0.8* |

| Bile acid % molar | 65 ± 2.8 | 62 ± 2.1 | 66 ± 2.7 |

| Phospholipids % molar | 25 ± 1.8 | 27 ± 1.4 | 28 ± 2.1 |

| Saturation Index (%) | 134 ± 18 | 152 ± 17 | 83 ± 12* |

| Cholic Acid (%) | 37 ± 2.3 | 31 ± 2.3 | 36 ± 2.5 |

| Chenodeoxycholic acid (%) | 35 ± 1.9 | 37 ± 3.1 | 41 ± 2.1 |

| Deoxycholic acid (%) | 25 ± 2.8 | 28 ± 4.7 | 20 ± 3.1 |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid (%) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 0.9 |

| Lithocholic acid (%) | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Plasma C4/cholesterol (ng/mmol/L) | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Campesterol/cholesterol (% variation from baseline) | 33 ± 53 | -5 ± 12 | 117 ± 28*** |

| Sitosterol/cholesterol (% variation from baseline) | 19 ± 23 | 5 ± 15 | 151 ± 33** |

Mean ± SEM;

vs. Placebo, p<0.05;

vs. Placebo, p<0.01;

vs. Placebo, p<0.001

Baseline values: Campesterol/cholesterol (μg/mmol): Placebo, 643 ± 157; Low ChSI, 654 ± 101; High ChSI, 662 ± 99. Sitosterol/cholesterol (μg/mmol): Placebo, 438 ± 72; Low ChSI, 492 ± 81; High ChSI, 452 ± 57.

Discussion

In this controlled single-blind parallel-group study, we were able to achieve our goal to obtain two widely different degrees of cholesterol synthesis inhibition (ChSI) by using a high dose of a potent statin (atorvastatin) and a low dose of a less potent statin (fluvastatin). The data were not intended to differentiate specific characteristics of either drug. Although, the use of two statins with different structure and metabolism may somewhat limit the interpretation of our results, some new as well as established molecular effects of low and high ChSI on hepatic cholesterol metabolism in humans could be identified.

In the present study, especially High-ChSI was associated with a decrease in plasma VLDL-cholesterol concentration, suggesting that a lesser amount of cholesteryl esters is secreted from the liver into nascent VLDL. We have recently demonstrated the hepatocyte-specific expression of ACAT2 and its significance in hepatic cholesterol esterification, 6, 11. Our new findings corroborate the hypothesis that ACAT2 is a key enzyme in the formation and secretion of cholesteryl esters in lipoproteins in humans 12. Accordingly, a clear decrease in hepatic ACAT2 activity and expression was observed in our patients in response to ChSI, whereas no treatment effects were identified for ACAT1 activity. In mice, hepatic ACAT2 has been shown to be essential for the incorporation of cholesteryl esters in the core of VLDL 13. Hence, our present findings suggest a key role for ACAT2 in hepatic VLDL cholesterol secretion also in humans.

While a decreased ACAT2 activity in part could account for the reduction in VLDL cholesterol secretion, it cannot be excluded that the secretion of apo B-containing lipoproteins from the liver is also decreased in High-ChSI by the higher LDL receptor expression. These receptors have been proposed to mediate the degradation of apo B before its secretion and to be responsible for the re-uptake and degradation of newly secreted apo B 14. We could indeed confirm and extend previous reports that the hepatic LDL receptor activity is increased following statin treatment in humans 15-17. Further, our data support the concept that also in humans a feed-forward regulation of the SREBP-2 gene expression is present, although the increase in SREBP-2 mRNA at High-ChSI was only of borderline significance. A trend towards an increase in PCSK-9 mRNA was also observed, indicating that this gene may also undergo regulation in humans 18, 19.

High-ChSI was associated with a reduced expression of apoE mRNA. Since apo E is a ligand for the LDL receptor, it might compete with apo B for binding to the LDL receptors within the secretory pathway of VLDL and/or at the cell surface. Hence, apo E has been predicted to have an opposite regulatory role on the secretion of VLDL in humans 14. Consistent with this hypothesis, genetically modified mice deficient in apo E have a reduced VLDL secretion20, 21 and mice overexpressing apoE have enhanced VLDL secretion 22. In contrast, we did not observe any changes in other genes involved in VLDL assembly and secretion, such as MTP or apo B. Thus, the upregulation of LDL receptors, the down regulation of apo E expression and the decrease in HMG CoA Red and ACAT2 activity could all contribute to the decrease in VLDL cholesterol levels that follows ChSI in humans.

In animal models of atherosclerosis, disruption of the ACAT2 gene leads to prevention of disease 23; this occurs despite elevations in plasma apo B. Consequently, not only the number of apo B-containing lipoproteins, but also the amount of ACAT2-derived cholesteryl esters present in the core of these lipoproteins seems to be critical factors in the development of atherosclerosis. All these observations indirectly suggest that a less atherogenic composition of the apo B-containing lipoproteins due to a decreased ACAT2 activity in the liver may convey an additional benefit following High-ChSI in humans. In mice, disruption of ACAT2 may result in a substitution of triglycerides for cholesteryl esters in the core of VLDL particles, resulting in increased plasma triglyceride levels 13, 23. At the level of ACAT2 inhibition achieved by ChSI in humans, this exchange does not seem to occur since the group of patients on High-ChSI presented the lowest level of ACAT2 activity and had the lowest plasma triglyceride levels. Furthermore, it has been shown that inhibition of cholesteryl ester production from ACAT2 by dietary polyunsaturated fat in non-human primates leads to a reduced LDL particle size37. How ACAT2 activity may modify LDL particle size in humans still remains to be studied. However, in contrast to humans, the size of LDL particles in non-human primates is mainly determined by the cholesteryl ester content since the extremely low levels of triglycerides do not allow for particle remodelling by triglyceride for cholesteryl ester exchange. Irregardless of possible effects of ACAT2 inhibition on LDL particle size, a decreased content of atherogenic cholesteryl esters (synthesized by ACAT2) in apo B containing lipoproteins should also be beneficial in humans. Studies in humans have also demonstrated that the amount of cholesterol per apo B in LDL particles, and not their size, is a strong risk factor for developing CVD 38.

In contrast to what has been observed in non-human primates - where the primary regulation of ACAT2 expression in the liver is not transcriptional 24 - the decreased mRNA expression of ACAT2 following ChSI in human beings indicates that sterols may also act as regulators of ACAT2 gene expression. In line with this, analysis of the transcriptional regulation of the ACAT2 gene in human hepatoma cell lines suggested a clear negative sterol regulation for this gene 39.

When High-ChSI was achieved by 80 mg/day atorvastatin, HDL cholesterol was reduced by 25% (Figure 2). In the present study, the cholesterol concentrations of lipoprotein fractions were calculated by integration of chromatograms obtained by size-exclusion analysis, a technique that has been shown to correlate well with ultracentrifugation/precipitation techniques 25. However, some degree of overestimation of the decrease in HDL and VLDL may result from the reduction of the LDL peak. We hypothesized that the reduction in HDL cholesterol might be linked to an increased CLA-I expression, which in turn could mediate increased HDL cholesterol uptake by the liver 9. However, CLA-I protein and gene expression were not changed after atorvastatin treatment, suggesting that other mechanisms explain the reduction in HDL cholesterol. Interestingly, evidence that the liver is the major source of cholesterol for lipidation of circulating HDL has been produced by disrupting hepatic ABCA1 in mice40. If the liver is also the source of much of the cholesterol in plasma HDL in humans, it may be speculated that the pool of cholesterol targeted for secretion into HDL may be reduced by a significant inhibition of cholesterol synthesis, as a partial explanation for the decrease in HDL cholesterol during high dose atorvastatin treatment.

High-ChSI resulted in a decrease in the cholesterol saturation of bile due to reduced molar % cholesterol, an effect that has been attributed to a decrease in biliary cholesterol secretion 41. ABCG5 and ABCG8 have been identified as the essential mediators of biliary cholesterol secretion from the canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte 42, and we hypothesized that changes in their expression might explain the reduction in biliary cholesterol. However, there were no effects of ChSI on mRNA levels for ABCG5 or ABCG8, nor on the protein level of ABCG8. This suggests that the reduced availability of hepatic cholesterol may more likely be the critical factor for biliary cholesterol secretion in our experimental model.

The increased plant sterol/cholesterol ratio in plasma observed after High-ChSI would suggest that intestinal cholesterol absorption may be increased, as proposed previously 10. However, the parallel observation of decreased molar % cholesterol content in bile may instead suggest that other mechanisms are involved. If the amount of biliary cholesterol reaching the intestine is reduced during High-ChSI, less cholesterol will be available for absorption and a relative enrichment of plant sterol would occur, explaining the paradoxical increase in plasma plant sterol/cholesterol ratio. Although speculative, this interpretation is indirectly supported by our finding of an inverse correlation between plasma plant sterol/cholesterol ratio and biliary molar % cholesterol.

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time in humans that a down-regulation of hepatic genes modulating cholesteryl ester composition and secretion of VLDL particles - ACAT2 and apo E – occurs following cholesterol synthesis inhibition. These effects should complement the beneficial changes in plasma LDL metabolism induced by increased LDL receptors, by acting also on the secretion of LDL-precursor lipoproteins. Statins have been previously shown to decrease plasma LDL cholesterol in patients homozygous for LDL receptor deficiency 43 and our observations may also provide a partial explanation for such LDL cholesterol decrease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosita Grundström, Lisbet Benthin and Ingela Arvidsson for technical assistance.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, NIH (HL-49373; HL-24736), the Swedish Medical Association, and from the Swedish Heart-Lung, Åke Wiberg, Fernström, and Throne Holst Foundations, and the Stockholm City Council.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Mats Eriksson and Paolo Parini are recipients of an unrestricted research grant from Pfizer AB, Sweden

References

- 1.Gotto AM., Jr Management of dyslipidemia. Am J Med. 2002;112 8A:10S–18S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedersen TR, Faergeman O, Kastelein JJ, Olsson AG, Tikkanen MJ, Holme I, Larsen ML, Bendiksen FS, Lindahl C, Szarek M, Tsai J. High-dose atorvastatin vs usual-dose simvastatin for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: the IDEAL study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005;294:2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence JM, Reid J, Taylor GJ, Stirling C, Reckless JP. The effect of high dose atorvastatin therapy on lipids and lipoprotein subfractions in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Harst P, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:714–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408123510719. author reply 714-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parini P, Davis M, Lada AT, Erickson SK, Wright LT, Gustafsson U, Sahlin S, Einarsson C, Eriksson M, Angelin B, Tomoda H, Omura S, Willingham MC, Rudel LL. ACAT2 is localized to hepatocytes and is the major cholesterol esterifying enzyme in human liver. Circulation. 2004;110:2017–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143163.76212.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudel LL, Lee RG, Parini P. ACAT2 is a target for treatment of coronary heart disease associated with hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1112–1118. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166548.65753.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafsson U, Sahlin S, Einarsson C. Biliary lipid composition in patients with cholesterol and pigment gallstones and gallstone-free subjects: deoxycholic acid does not contribute to formation of cholesterol gallstones. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:1099–1106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rigotti A, Miettinen HE, Krieger M. The role of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI in the lipid metabolism of endocrine and other tissues. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:357–387. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miettinen TA, Gylling H, Lindbohm N, Miettinen TE, Rajaratnam RA, Relas H. Serum noncholesterol sterols during inhibition of cholesterol synthesis by statins. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;141:131–137. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pramfalk C, Davis MA, Eriksson M, Rudel LL, Parini P. Control of ACAT2 liver expression by HNF1. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1868–1876. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400450-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudel LL, Lee RG, Cockman TL. Acyl coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase types 1 and 2: structure and function in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:121–127. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee RG, Kelley KL, Sawyer JK, Farese RV, Jr, Parks JS, Rudel LL. Plasma cholesteryl esters provided by lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and acyl-coenzyme a:cholesterol acyltransferase 2 have opposite atherosclerotic potential. Circ Res. 2004;95:998–1004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147558.15554.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twisk J, Gillian-Daniel DL, Tebon A, Wang L, Barrett PHR, Attie AD. The role of the LDL receptor in apolipoprotein B secretion. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:521–532. doi: 10.1172/JCI8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reihnér E, Rudling M, Ståhlberg D, Berglund L, Ewerth S, Björkhem I, Einarsson K, Angelin B. Influence of pravastatin, a specific inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, on hepatic metabolism of cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:224–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudling MJ, Reihnér E, Einarsson K, Ewerth S, Angelin B. Low density lipoprotein receptor-binding activity in human tissues: quantitative importance of hepatic receptors and evidence for regulation of their expression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3469–3473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudling M, Angelin B, Stahle L, Reihner E, Sahlin S, Olivecrona H, Bjorkhem I, Einarsson C. Regulation of hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, and cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase mRNAs in human liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4307–4313. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-012041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson LM, Abrahamsson A, Sahlin S, Gustafsson U, Angelin B, Parini P, Einarsson C. Bile acids and lipoprotein metabolism: effects of cholestyramine and chenodeoxycholic acid on human hepatic mRNA expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubuc G, Chamberland A, Wassef H, Davignon J, Seidah NG, Bernier L, Prat A. Statins upregulate PCSK9, the gene encoding the proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase-1 implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1454–1459. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134621.14315.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuipers F, Jong MC, Lin Y, Eck M, Havinga R, Bloks V, Verkade HJ, Hofker MH, Moshage H, Berkel TJ, Vonk RJ, Havekes LM. Impaired secretion of very low density lipoprotein-triglycerides by apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse hepatocytes. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2915–2922. doi: 10.1172/JCI119841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maugeais C, Tietge UJ, Tsukamoto K, Glick JM, Rader DJ. Hepatic apolipoprotein E expression promotes very low density lipoprotein-apolipoprotein B production in vivo in mice. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1673–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Liu XQ, Rall SC, Jr, Taylor JM, von Eckardstein A, Assmann G, Mahley RW. Overexpression and accumulation of apolipoprotein E as a cause of hypertriglyceridemia. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26388–26393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willner EL, Tow B, Buhman KK, Wilson M, Sanan DA, Rudel LL, Farese RV., Jr Deficiency of acyl CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase 2 prevents atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1262–1267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336398100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudel LL, Davis M, Sawyer J, Shah R, Wallace J. Primates highly responsive to dietary cholesterol up-regulate hepatic ACAT2, and less responsive primates do not. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31401–31406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parini P, Johansson L, Bröijersén A, Angelin B, Rudling M. Lipoprotein profiles in plasma and interstitial fluid analyzed with an automated gel-filtration system. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]