Positron emission tomography (PET) has emerged as a prevailing noninvasive research tool to understand biochemical processes and elucidate molecular interactions relevant to human health.[1] The enabling technology that underlies PET and other radiotracer imaging methods is radiotracer chemistry. Thus, the continued success and expanded capability of PET relies on the development of methods to incorporate positron emitting isotopes into compounds, which for example, can serve as biomarkers for human disease. Arguably, one of the most important isotopes for PET research is carbon-11 (t1/2 = 20.4 min) due to its ubiquity in pharmacologically active compounds and its favourable physical properties.[2] However, only a limited number of reactions that meet the special demands and constraints of carbon-11 chemistry have been developed.[3] Even fewer are routinely employed due to process complexity and/or the requirement for special equipment. Recently, we have placed a focus on developing chemical methods for carbon-11 labelling that can be easily and immediately implemented[4] and herein we describe a new method that addresses the carbamate function group.[5]

Synthesis with carbon-11 begins with a nuclear reaction (typically, [14N(p,α)11C]) using a cyclotron that produces 11CO2 or 11CH4.[6] In most cases, this “starting material” must be rapidly converted to a more useful reagent, for example 11CH3I,[7] which is then used to label a precursor compound. The process of reagent synthesis alone can consume more than half of the radioactivity (considering decay during reaction time x yield of each conversion step x trapping efficiency).[8] In this respect, chemical reactions that use 11CO2 or 11CH4 directly have a clear advantage in terms of radiochemical yield and if properly designed, direct incorporation strategies can eliminate or reduce the need for special equipment.

With this in mind, we have developed a one-pot, operationally simple method for the direct incorporation of 11CO2 into carbamate-containing compounds. This functional group is an attractive target for radiochemical incorporation in light of its versatility for modular construction of organic compounds and its chemical and metabolic stability. Other methods to label the carbamate carbon have utilized [11C]phosgene,[9] or [11C]carbon monoxide,[10] both of which present technical difficulties and equipment needs that currently make their routine use somewhat impractical.

Our development was guided by previous research using excess, typically high pressure, carbon dioxide in a variety of chemical fixation reactions[11] including carbamate synthesis.[12] However, at the outset we anticipated significant differences in reactions using trace carbon dioxide (11CO2) at atmospheric pressure and recognized process differences that would dictate general applicability and use of a new radiochemical method. Previous studies[13] demonstrated the feasibility of using no carrier added 11CO2 in the conversion of amines to isocyanates and ureas. Encouraged by these studies, we examined a variety of reaction conditions using substoichiometric 12CO2 in model reactions. In addition, we optimized 11CO2 trapping efficiency at room temperature, capture flow rate, solvent and catalyst/base identity through screening.[14]

From these preliminary experiments, we quickly identified DBU (1,8-diaza-bicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene) as both a superior trapping reagent and a catalyst for the reaction. Solutions of DBU (100 mM) in MeCN, DMF, and DMSO trapped >95% of 11CO2 from a constant flow of He (50 ml/min) whereas for comparison, solvent and solutions of DMAP (4-(dimethylamino)-pyridine) or DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]-octane) trapped <10%.

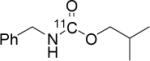

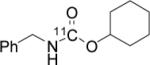

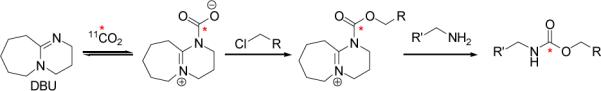

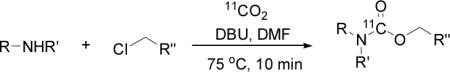

Carbon-11 reaction optimization was carried out with operational simplicity in mind. Conceptually, the reaction occurs as detailed in Scheme 1; however, it is most likely that many equilibria exist in solution and that (bi)carbonate salts of DBU are important reactive intermediates.[14, 15]

Scheme 1.

Conceptual mechanism for DBU-catalyzed incorporation of [11C]carbon dioxide

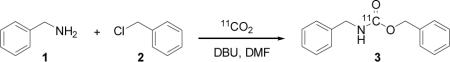

In one-pot, solutions of benzyl amine (1), benzyl chloride (2), and DBU were combined and the resulting solution was used to trap 11CO2 (10-40 mCi) from a constant stream of He (in <2 min) using a standard cone-bottomed glass vial with septum and screw cap. The inlet and outlet lines were removed or closed and the reaction solution was heated. At the end of a given reaction time, the reaction was quenched by the addition of excess acid and the amount of volatile radioactivity (i.e. unreacted 11CO2) was determined. A sample was then analyzed by radioTLC or radioHPLC for chemical identity and radiochemical purity. From these data, we calculated radiochemical yield under various reaction conditions, Table 1.

Table 1.

Preliminary reaction optimizationa

| Entry | [1] mM | [2] mM | [DBU] mM | time/min | temp/°C | %yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 5.0 | 75 | 60 |

| 2 | " | " | " | 5.0 | 100 | 69 |

| 3 | " | " | " | 7.5 | 75 | 81 |

| 4 | " | " | " | 7.5 | 100 | 83 |

| 5 | " | " | " | 10 | 25 | 17 |

| 6 | " | " | " | 10 | 75 | 85 |

| 7 | " | " | " | 10 | 100 | 75 |

| 8 | " | " | " | 12 | 75 | 83 |

| 9 | " | " | " | 12 | 100 | 81 |

| 10 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 10 | 75 | 73 |

| 11 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 75 | 51 |

| 12 | 100 | 100 | 10 | 10 | 75 | 10 |

| 13 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 10 | 75 | 7 |

Reactions (300 μL DMF) were performed in a sealed vessel under a He atmosphere. No carrier added 11CO2 was trapped from a stream of He gas.

See supporting information for details related to radiochemical yield calculation.

The desired [11C]-carbamate was formed in high radiochemical yield in under 10 min at slightly elevated temperatures, Table 1 entry 6. At room temperature the reaction occurred in lower yield, but perhaps sufficient for labeling temperature-sensitive compounds. When compared to other carbon-11 labeling methods, bear in mind that the entire process including trapping and reaction time can be accomplished in less than 10 min. Therefore, non-decay corrected yields (i.e. deliverable yields) are much higher for this direct 11CO2 method than for other more time intensive labeling strategies.[16]

From this series of experiments we determined that radiochemical yield was more sensitive to DBU and benzyl chloride concentrations than benzyl amine concentration. In the absence of DBU a small amount of labeling was observed, however the trapping efficiency was poor. In the absence of benzyl amine, we observed <1% formation of [11C]-dibenzyl carbonate. This may indicate that the soluble [11C]-carbonate salt of DBU is not participating or is alkylated reversibly thus releasing 11CO2 upon acidification. The only productive (irreversible) and high yielding pathway involved the amine. In fact, the use of a mixture of benzyl alcohol, benzyl chloride, and DBU under the optimized reaction conditions provided less than 3% radiochemical yield of [11C]-dibenzyl carbonate.

For the reactions we have reported in Table 1, we used dry solvents that were stored over molecular sieves. However, we found that dry solvents were not necessary and even in the presence of 10 mg of water, the reaction yields were comparably high. We have not eliminated the possibility that water is important in the reaction and are working to perform the reaction under rigorously anhydrous conditions to determine if water plays an essential role in the mechanism. We have found that the use of NaOH (aq) in DMF under the same conditions is not effective, but mechanisms involving water with DBU cannot be excluded. Clearly, the role of DBU in sequestering CO2 either as a zwitterion or (bi)carbonate salt is important, but the precise nature of this interaction and related reactive intermediate(s) cannot yet be discerned, especially when tracer quantities (i.e. nanomoles) of 11CO2 are being employed.[14]

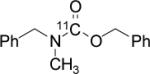

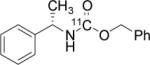

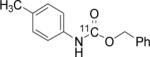

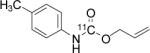

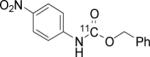

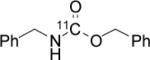

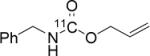

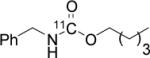

To probe the scope of this direct 11CO2 incorporation method, we examined the reaction of a series of amines and alkyl halides, Table 2. Secondary and di-substituted amines formed the corresponding [11C]-carbamates in good yields, Table 2 (entries 1-5). Less nucleophilic amines, such as anilines, participated in the reaction but with lower levels of conversion under these conditions. Given the simplicity of the reaction, direct use of 11CO2, and short reaction times, we anticipate that even these lower radiochemical yields will be competitive with alternative methods for carbamate labelling. We are currently investigating reaction conditions and co-catalysts to increase the radiochemical yields for less nucleophilic amines and for alcohols.[17]

Table 2.

DBU mediated incorporation of 11CO2: scopea

All reactions were carried out with 100 mM of amine, alkyl chloride, and DBU in 300 μL of DMF.

Average radiochemical yield of two or more reactions.

Radiochemical yield for the corresponding alkyl bromide.

mean ± stdev (n = 10).

In terms of electrophile scope, we examined the reaction of benzyl amine with a series of alkyl halides, Table 2 (entries 6-10). For the desired 11CO2 reaction to occur in acceptable radiochemical yield, electrophile reactivity had to be modulated so that competitive alkylation of the amine or DBU and elimination of the alkyl halide were minimal. In general, alkyl chlorides were better than the corresponding bromides. However in some cases, alkyl bromides were more effective. In these cases, alkylation of the amine was not competitive, (Table 2 entry 8). Hence, the reactivity can be “tuned” by the choice of an appropriate nucleophile / leaving group pair and we are now determining the extent to which we can develop rules to guide such pair selections, thus expanding the scope and predictability of high yielding reactions.

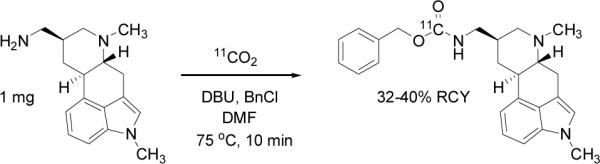

Finally, to test the reaction in the context of a pharmacologically active compound with potential as a PET imaging tracer, we labeled metergoline,[18] a serotonin (5HT) receptor antagonist, Scheme 2. It is worth noting that benzyl carbamate containing molecules like metergoline are attractive targets for this methodology because the labelling precursor (amine) can be produced by deprotection using H2 and Pd/C. (We anticipate similar strategies for other common carbamates, which are used as protecting groups.) The reaction setup was extremely simple consisting of one vessel. 11CO2 was trapped in the 300 μL reaction solution (containing 100 mM DBU, 1 mg of the amine precursor, 100 mM benzyl chloride) directly from the cyclotron target gases. Given the simplicity of the method and the short overall process and reaction time from the end-of-bombardment (EOB), the radiochemical yield was excellent (32% calculated to EOB). We have now scaled this reaction in terms of radioactivity using up to 400 mCi of 11CO2 and can produce [11C]-metergoline at high specific activity (up to 5 Ci/μmol) using less than 1 mg of precursor. (The evaluation of [11C]-metergoline as a radiotracer for the 5HT receptor system in the brain will be reported elsewhere.)

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of [11C]-metergoline

In summary, the direct incorporation of 11CO2 into the carbamate functional group has been demonstrated. We are currently optimizing additional parameters to improve radiochemical yield and reaction scope. However, the simplicity and efficiency of the reaction should immediately provide new capabilities to carbon-11 chemists and expand the number and types of molecules useful in PET and other radiotracer applications. We are currently working to better understand the mechanism and the role DBU plays under tracer-scale conditions.

Experimental Section

Separate solutions (300 mM each) of the amine, DBU, and alkyl chloride were prepared in DMF (that had been previously sparged with He gas to remove any CO2 from the atmosphere). Aliquots (100 μl) of each solution were combined in a reaction vessel, which was then sealed with a septum and screw cap. The resulting 300 μl solution (0.1 M in each reagent) was sparged with He gas for 2-3 min. [11C]Carbon dioxide was released in a stream of He (~50 mL/min) from an automated trap and release system and introduced to the reaction solution under constant flow at room temperature. The amount of 11CO2 trapped was monitored and recorded and the capture step continued until the radioactivity curve reached a maximum (typically <2 min). After removing the inlet and outlet needles, the sealed vessel was transferred into a heating bath. Most reactions were carried out for 10 min at 75 °C. Other conditions are noted in Table 1. To determine radiochemical yield, reaction solutions were placed in contact with a miniature radiation detector and equipped with an inlet and outlet line using needles through the septa cap. The solution was acidified with 100 μL of 1.0 M HCl (an excess relative to DBU and amine). The residual 11CO2 trapped in solution was then removed from solution by sparging with a stream of He gas (~50 ml/min). When the radioactivity in the solution became constant (ignoring decay), an aliquot of the solution was analyzed by radio-TLC and/or radio-HPLC. The percentage of radioactivity coincident with reference compound was multiplied by the decay corrected percentage of radioactivity that remained in solution upon removal of excess 11CO2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out at Brookhaven National Laboratory (contract DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy and supported by its Office of Biological and Environmental Research). J.M.H. was supported by the NIH (1F32EB008320-01) and a Goldhaber Fellowship at BNL. A.T.R was supported by Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) and BNL.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1].Wahl RL. Principles and Practice of PET and PET/CT. 2nd Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Antoni G, Kihlberg T, Långström B. Aspects on the synthesis of 11C-labeled compounds. In: Welch MJ, Redvanly CS, editors. Handbook of Radiopharmaceuticals: Radiochemistry and Applications. 2003. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8998. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Allard M, Fouquet E, James D, Szlosek-Pinaud M. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:235. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hooker JM, Schoenberger M, Schieferstein H, Fowler JS. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2008;47:5989. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schoultz BW, Årstad E, Marton J, Willoch F, Drzezga A, Wester H-J, Henriksen G. Open Med. Chem. J. 2008;2:72. doi: 10.2174/1874104500802010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A new, practical method for the synthesis of methyl carbamates from 11CH3I was recently reported:

- [6].Christman DR, Finn RD, Karlstrom KI, Wolf AP. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1975;26:435. [Google Scholar]

- [7].(a) Långström B, Lundqvist H. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1976;27:357. doi: 10.1016/0020-708x(76)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Link JM, Krohn KA, Clark JC. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1997;24:93. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Fowler JS, Wolf AP. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997;30:181. [Google Scholar]; (b) Långström B, Kihlberg T, Bergstrom M, Antoni G, Bjorkman M, Forngren BH, Forngren T, Hartvig P, Markides K, Yngve U, Ogren M. Acta Chem. Scand. 1999;53:651. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.53-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lemoucheux L, Rouden J, Ibazizene M, Sobrio F, Lasne MC. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7289. doi: 10.1021/jo0346297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].(a) Kihlberg T, Karimi F, Långström B. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3687. doi: 10.1021/jo016307d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Doi H, Barletta J, Suzuki M, Noyori R, Watanabe Y, Långström B, B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:3063. doi: 10.1039/B409294E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Costa M, Chiusoli GP, Rizzardi M. Chem. Commun. 1996:1699. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chaturvedi D, Chaturvedi AK, Mishra N, Mishra V. Synthetic Commun. 2008;38:4013. [Google Scholar]

- [12].(a) Shi M, Shen YM. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2001;84:3357. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dell'Amico DB, Calderazzo F, Labella L, Marchetti F, Pampaloni G. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3857. doi: 10.1021/cr940266m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chaturvedi D, Ray S. Monatsh. Chem. 2006;137:127. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tascedda P, Dunach E. Chem. Commun. 2000:449. [Google Scholar]; (e) Aresta M, Quaranta E. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:1515. [Google Scholar]; (f) Pérez ER, da Silva MO, Costa VC, Rodrigues-Filho UP, Franco DW. Tet. Lett. 2002;43:4091. [Google Scholar]

- [13].(a) Schirbel A, Holschbach MH, Coenen HH. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 1999;42:537. [Google Scholar]; (b) Van Tilburg EW, Windhorst AD, Van der Mey M, Herscheid JDM. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2006;49:321. [Google Scholar]

- [14].See supporting information for CO2 model reactions, 11CO2 trapping experiments, and additional mechanism discussion.

- [15].(a) Heldebrant DJ, Jessop PG, Thomas CA, Eckert CA, Liotta CL. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:5335. doi: 10.1021/jo0503759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mcghee W, Riley D, Christ K, Pan Y, Parnas B. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:2820. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pérez ER, Santos RHA, Gambardella MTP, de Macedo LGM, Rodrigues-Filho UP, Launay JC, Franco DW. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8005. doi: 10.1021/jo049243q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Masuda K, Ito Y, Horiguchi M, Fujita H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:213. [Google Scholar]; Mechanistic details related to the role of DBU and alkyl amines in similar reactions have been discussed extensively. For examples, see:

- [16].Wuest FR. Trends in Org. Chem. 2003;10:61. [Google Scholar]; For further discussion, see:

- [17].Shen YM, Duan WL, Shi M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003;345:337. [Google Scholar]; Co-catylsts have been successfully employed in CO2 reactions involving epoxides.

- [18].Beretta C, Ferrini R, Glasser AH. Nature. 1965;207:421. doi: 10.1038/207421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.