Abstract

The pseudopilus is a key feature of the type 2 secretion system (T2SS) and is made up of multiple pseudopilins that are similar in fold to the type 4 pilins. However, pilins have disulfide bridges, whereas the major pseudopilins of T2SS do not. A key question is therefore how the pseudopilins, and in particular, the most abundant major pseudopilin, GspG, obtain sufficient stability to perform their function. Crystal structures of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus, and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) GspG were elucidated, and all show a calcium ion bound at the same site. Conservation of the calcium ligands fully supports the suggestion that calcium ion binding by the major pseudopilin is essential for the T2SS. Functional studies of GspG with mutated calcium ion-coordinating ligands were performed to investigate this hypothesis and show that in vivo protease secretion by the T2SS is severely impaired. Taking all evidence together, this allows the conclusion that, in complete contrast to the situation in the type 4 pili system homologs, in the T2SS, the major protein component of the central pseudopilus is dependent on calcium ions for activity.

In Gram-negative bacteria, the type 2 secretion system (T2SS)2 is used for the secretion of several important proteins across the outer membrane (1). The T2SS is also called the terminal branch of the general secretory pathway (Gsp) (2) and, in Vibrio species, the extracellular protein secretion (Eps) apparatus (3). This sophisticated multiprotein machinery spans both the inner and the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and contains 11–15 different proteins. The T2SS consists of three major subassemblies (4–9): (i) the outer membrane complex comprising mainly the crucial multisubunit secretin GspD; (ii) the pseudopilus, which consists of one major and several minor pseudopilins; and (iii) an inner membrane platform, containing the cytoplasmic secretion ATPase GspE and the membrane proteins GspL, GspM, GspC, and GspF.

The pseudopilus is a key element of the T2SS that forms a helical fiber spanning the periplasm. The fiber is assembled from multiple subunits of the major pseudopilin GspG (4, 5, 10–14). The pseudopilus is thought to form a plug of the secretin pore in the outer membrane and/or to function as a piston during protein secretion. In recent years, studies of the T2SS pseudopilins led to structure determinations of all individual pseudopilins (13, 15–17). The recent structure of the helical ternary complex of GspK-GspI-GspJ suggested that these three minor pseudopilins form the tip of the pseudopilus (17). A crystal structure of GspG from Klebsiella oxytoca was in a previous study combined with electron microscopy data to arrive at a helical arrangement, with no evidence for special features, such as disulfide bridges, other covalent links, or metal-binding sites, for stabilizing this major pseudopilin or the pseudopilus (13).

The pseudopilins of the T2SS share a common fold with the type 4 pilins (15–21). Pilins are proteins incorporated into pili, long appendages on the surface of bacteria forming thin, strong fibers with multiple functions (19, 21). Type 4 pilins and pseudopilins contain a prepilin leader sequence that is cleaved off by a prepilin peptidase, yielding mature protein (10, 11, 22). A distinct feature of the type 4 pilins is the occurrence of a disulfide bridge connecting β4 to a Cys in the so-called “D-region” near the C terminus (21). In a recent study (23) on the thin fibers of Gram-positive bacteria, isopeptide units appeared to be essential for providing these filaments sufficient cohesion and stability. A key question was therefore whether the major pseudopilin GspG also requires a special feature to obtain sufficient stability to perform its function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression, Purification, and Crystallization of Vibrio cholerae GspG

The gene fragment corresponding to the soluble domain of V. cholerae GspG (residues 26–137) was cloned into a pCDFDuet-1-based vector (Novagen) for expression with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag followed by a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli cells were grown in Luria broth at 37 °C and induced for 3 h with 0.5 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 30 °C. GspG was purified from the soluble fraction of the lysed cells using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Qiagen) followed by His tag cleavage with tobacco etch virus protease, an ion-exchange purification step using a 30Q column (GE Healthcare), and a final size exclusion on a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) for both ion-exchange peaks. After dialysis against 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.0, crystals were obtained only for the first ion-exchange peak. The optimized crystals were grown using the vapor diffusion method in 22.5% polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.1 m sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 0.04 m zinc acetate.

Structure Determination of V. cholerae GspG

The crystals diffracted to ∼4 Å initially. After two cycles of crystal annealing by blocking the cryo-stream, the resolution limit improved to 2.5 Å, and a preliminary data set was collected in-house (supplemental Table 1). Data were processed using HKL2000 (24). The structure was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (25) using the structure of K. oxytoca GspG (13) as a model. In the search model, the non-equivalent residues were truncated to Ala/Gly, and the swapped β4-strand was removed. After density modification with Resolve (26), it was apparent that there are several metal ions in the structure. Those ions were initially thought to be Zn2+ ions present in the crystallization solution. Therefore, the data were collected at zinc remote and inflection wavelengths at beamline BL9-2 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL).

Using anomalous data from either zinc remote or a combination of zinc remote/inflection data sets, SHELXD (27) found three zinc positions, two with full occupancy and one with ∼50% occupancy. The initial model was improved using ARP/wARP (28) and finalized using manual rebuilding in Coot (29) alternating with refinement by REFMAC5 (30) using one TLS group per chain. From subsequent tests, it appeared that the structure could have been solved ab initio using the zinc anomalous signal. The two monomers in the asymmetric unit (ASU) form an antiparallel dimer with two Zn2+ ions in the interface and a third Zn2+ ion participating in crystal contact with a symmetry-related molecule (Fig. 1). The two monomers superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 0.4 Å over 112 Cα atoms.

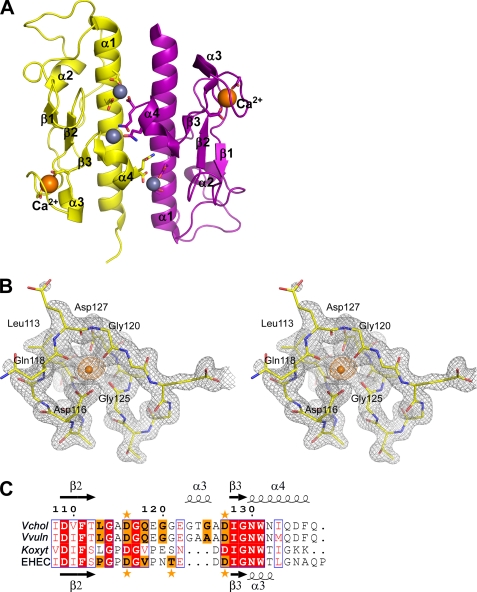

FIGURE 1.

Structure and calcium-binding site of V. cholerae GspG. A, the two V. cholerae GspG subunits per ASU are shown in yellow and purple. Orange and gray spheres indicate calcium and zinc ions, respectively. Side chains of residues coordinating calcium or zinc ions are shown in stick representation. B, stereo representation of electron density in the Ca2+-binding site. The 2Fo − Fc map is contoured at 1.2 σ displayed as gray mesh. The calcium ion is surrounded by anomalous difference Fourier electron density colored in orange, calculated using data to 2.5 Å resolution collected at λ = 1.28344Å and contoured at 4 σ. For the essentially identical arrangement in V. vulnificus GspG, see supplemental Fig. 2. C, sequence alignment of the Ca2+-binding regions of the four major pseudopilins with known structure (V. cholerae (Vchol), V. vulnificus (Vvuln), EHEC, and K. oxytoca (Koxyt) GspG). Residues involved in Ca2+ binding, either by main chain or by side chain oxygens, are highlighted in orange. The conserved Ca2+ site aspartate ligands are indicated with an orange asterisk on top and below; the liganding Thr in EHEC, and by analogy Ser-122 in K. oxytoca GspG, is indicated with an orange asterisk below. Secondary structure elements above and below displayed sequences correspond to V. cholerae and EHEC GspG structures, respectively.

Expression and Purification of Vibrio vulnificus and EHEC GspG

The gene fragments corresponding to the soluble domains of V. vulnificus GspG (residues 26–137) and EHEC GspG (residues 17–136) were cloned into a pCDFDuet-1-based vector similar to V. cholerae GspG. The expression was performed as for V. cholerae GspG, except that Luria broth was supplemented with 1 mm calcium chloride, but no calcium chloride was added during subsequent purification and crystallization. The purification followed the procedure outlined for V. cholerae GspG with the first ion-exchange peak used for crystallization.

Crystallization and Structure Determination of V. vulnificus GspG

Crystals of V. vulnificus GspG were grown using the vapor diffusion method in 1.95 m dl-malic acid, pH 5.0. A data set was collected at beamline BL9-2 at SSRL (supplemental Table 1). Data were processed using XDS (31). The structure was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (25) using the V. cholerae GspG structure as a model. After manual rebuilding in Coot (29), the three monomers in the ASU were refined with REFMAC5 (30) using three TLS groups per chain as defined by the TLSMD server (32). The three subunits in the ASU superimpose pairwise with an r.m.s.d. of 0.2–0.4 Å over 111 Cα atoms. The V. vulnificus GspG structures superimpose onto the V. cholerae GspG structures with an r.m.s.d. of 0.6–0.8 Å over 111 Cα atoms and 91% sequence identity in the superimposed region.

Crystallization and Structure Determination of EHEC GspG

A cluster of crystals was obtained during screening in a condition containing 1.0 m sodium citrate, 0.1 m CHES, pH 9.5. An individual crystal was separated from the cluster, frozen, and used for data collection. Data were collected at beamline BL9-2 at SSRL and processed using XDS (31). The structure was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (25) using the V. cholerae GspG structure, with the Ca2+-binding loop and C-terminal α-helix removed, as a search model. The two monomers in the ASU were rebuilt using ARP/wARP (28) and finalized using Coot (29). The structure was refined with REFMAC5 (30) using three TLS groups per chain as defined by the TLSMD server (32). The two subunits in the ASU superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 2.0 Å over 114 Cα atoms. Large differences occur only in the N-terminal region where helix α1 unwinds. The exclusion of residues 18–29 from the superimposition reduces the r.m.s.d. to 0.5 Å. Superimposition onto the V. cholerae GspG structure gives an r.m.s.d. of 1.9–2.1 Å over 105 Cα atoms with 65% sequence identity in the superimposed region.

Functional Secretion Studies of GspG Mutants

The ΔgspG strain and the complementing pMMB67EH-gspG plasmid were constructed as described previously (33). Mutations were introduced in gspG gene with QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using pMMB-gspG as a template. Primers used for the site change in gspGD116A and gspGD127A were 5′-gttcaccttaggtgcggccggtcaagaaggtggtg-3′, 3′-caagtggaatccacgccggccagttcttccaccac-5′, 5′-gaaggtaccggtgccgctatcggtaactgg-3′, and 3′-cttccatggccacggcgatagccattgacc-5′, respectively. gspGD116AD127A was then constructed using pMMB-gspGD116A as a template and the above primers specific for the gspGD127A site change. All mutations were verified by sequencing.

Detection of Secreted Protease Activity

Cultures were grown overnight in Luria broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml thymine and 200 μg/ml carbenicillin and centrifuged to separate the supernatant and cellular material. The supernatants were centrifuged once more, and the protease activity was measured as described previously (4).

Immunoblotting for GspG

Cultures were grown to mid-log phase. Whole cell lysates were prepared by resuspending cells in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 50 mm dithiothreitol and boiling for 5 min. 10 μl of A600 = 1.0 was loaded onto NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gels (Invitrogen). Following electrophoresis and immunoblotting, GspG was detected with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against V. cholerae GspG, kindly supplied by Dr. Michael Bagdasarian, Michigan State University, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad), and ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare). Typhoon Trio variable mode imager system and ImageQuant software were used for imaging.

Fluorescence-based Thermal Shift Assay

The soluble domain of the V. cholerae GspG double D116A/D127A mutant (residues 26–137) was expressed and purified similar to the wild-type protein. A single peak was obtained after the ion-exchange step. The thermal stability of proteins was measured by fluorescence using SYPRO Orange as fluorophore as described elsewhere (34), without additives, in the presence of 1 mm calcium chloride or in the presence of 1 mm EDTA. Four independent values were measured for each condition. The melting temperature (Tm) of wild-type GspG was 50.0 ± 1.0, 56.2 ± 0.3, and 40.1 ± 0.4 °C for no additive, calcium chloride, and EDTA conditions, respectively. Tm values for the double D116A/D127A mutant were 46.4 ± 0.6, 46.4 ± 0.5, and 46.2 ± 0.4 °C for no additive, calcium chloride, and EDTA conditions, respectively.

Structure Analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were made using ClustalW2 (35). ESPript (36) was applied to render the alignments. The figures were generated using PyMOL (37).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We solved the crystal structures of V. cholerae, V. vulnificus, and EHEC GspGs, all to better than 2.0 Å resolution, yielding a total of seven views of these three GspG molecules (supplemental Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2, and supplemental Fig. 2). All these structures largely agree with the structure of K. oxytoca GspG and show the typical pilin fold composed of an N-terminal α-helix, a “variable segment,” and a C-terminal β-sheet. However, we consistently found two additional structural features that have not been described previously. First, the C-terminal residues in all new GspG structures adopt a helical conformation (Figs. 1 and 2 and supplemental Fig. 2), in contrast with a β-strand observed in K. oxytoca GspG. In the latter structure, a β-strand swap occurred between the two pseudopilin molecules in the asymmetric unit (13). Second, a distinct high electron density is present in each of the two subunits of the V. cholerae GspG structure, surrounded by the carboxylates of Asp-116 and Asp-127 and by four main chain carbonyl oxygens (from Leu-113, Gln-118, Gly-120, and Gly-125) in an octahedral manner.

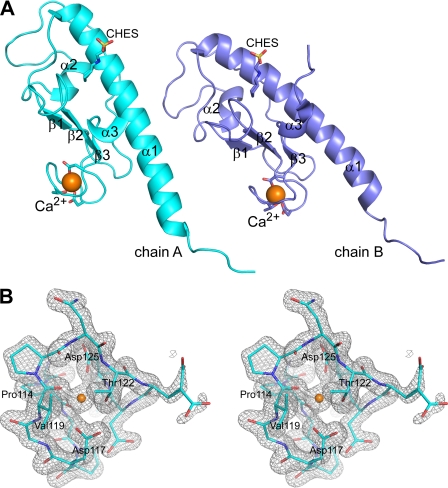

FIGURE 2.

Structure and calcium-binding site of EHEC GspG. A, the two EHEC GspG subunits per asymmetric unit are shown in light and dark blue. Orange spheres indicate calcium ions. Side chains of residues coordinating calcium ions are shown in stick representation, as are buffer CHES molecules. B, stereo representation of electron density in the Ca2+-binding site. The 2Fo − Fc map is contoured at 1.2 σ displayed as gray mesh.

The high density of the peak (Fig. 1B) and the all-oxygen sphere of ligands provided initial evidence that the ion bound is a calcium ion. Additional evidence that the two ions located in the β2-β3 loop are calcium ions is: (i) the anomalous difference maps using the λ = 0.97946 Å data reveal 4.7 and 3.6 σ peaks (Fig. 1B) at the Ca2+-binding sites, which is proportional to the 22.5 and 20.3 σ peaks at the zinc positions with full occupancy, because the f″ = 0.56 electrons for Ca2+ and the f″ = 2.48 electrons for Zn2+ at this wavelength; (ii) the anomalous difference maps in the λ = 1.28344 Å data set show 7.3 and 5.3 σ peaks at the two Ca2+-binding sites when compared with the 12.8 and 8.0 σ peaks at the zinc positions with full occupancy, which agrees with the f″ = 0.93 electrons for Ca2+ and the f″ = 1.21 electrons for Zn2+ at this wavelength; (iii) refinement as calcium ions at full occupancy yields temperature factors for the cations of 26.5 Å2 in chain A and 48.7 Å2 in chain B, which are close to the average temperature factors of 27.7 and 49.1 Å2, respectively, for the coordinating oxygen atoms.

The structure determinations of V. vulnificus and EHEC GspG were undertaken to evaluate the presence of Ca2+ ions across the GspG family. In the V. vulnificus structure, the calcium-binding regions of the three independent subunits have higher B factors than the rest of the structure, yet the evidence of calcium binding is clear. The anomalous difference maps (supplemental Fig. 2C), using the λ = 1.5418 Å data, reveal 12.9, 9.7, and 5.0 σ peaks at the Ca2+-binding sites in chains A, B, and C, respectively, corresponding with the f″ of 1.29 electrons for Ca2+ at this wavelength. The side chain of Asp-116 in chain C swings out of the Ca2+-binding site to participate in a water-mediated crystal contact. Based on the values of anomalous peaks, we refined the Ca2+ ion in chain C at 50% occupancy. Refinement of the calcium ions yields temperature factors of 70.6 Å2 in chain A, 79.2 Å2 in chain B, and 87.3 Å2 in chain C, which are close to the average temperature factors of 66.6, 78.1, and 78.6 Å2, respectively, for the coordinating atoms.

The amino acid sequences of GspGs from EHEC and K. oxytoca align well mutually but display distinct sequence variation in the Ca2+-binding region when compared with those of V. cholerae and V. vulnificus GspGs. The latter proteins have an insert of three residues, forming helix α3 in the Vibrio GspG structures, between the two conserved calcium-coordinating aspartates (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. 1). Nevertheless, in the EHEC GspG structure, both subunits show a high electron density consistent with Ca2+ binding in essentially the same position as in V. cholerae and V. vulnificus GspG. The temperature factors for the metal ions with full occupancy are 34.2 Å2 in chain A and 27.6 Å2 in chain B, which are close to the average temperature factors of 21.2 and 18.7 Å2, respectively, for the coordinating atoms. The charged ligands of the EHEC calcium site are Asp-117 and Asp-125, which are structurally equivalent to Asp-116 and Asp-127 of V. cholerae GspG, with as new ligand the hydroxyl of Thr-122 and with the carbonyl oxygens of Pro-114 and Val-119 completing the plane of a trigonal bipyramidal coordination (Fig. 2B). The all-oxygen coordination of the ion site is in agreement with Ca2+ binding.

The GspG family sequence alignment (supplemental Fig. 1) indicates that the two Ca2+-coordinating aspartates are conserved, are rarely a Glu, and only in Legionella pneumophila is one an alanine (not shown). Note also how the Thr/Ser presence in the Ca2+-binding site correlates consistently with the omission of three residues, forming the V. cholerae GspG helix α3, in the β2-β3 loop. There appear therefore to be two subclasses of major pseudopilins. One is a Vibrio-like subclass, with four main chain carbonyl oxygen calcium-binding ligands plus two carboxylate ligands and a short helix α3 between the two carboxylate-providing amino acids. The second is the EHEC-like subclass, with two main chain calcium-binding ligands, one Thr/Ser side chain oxygen ligand plus two carboxylate ligands, and no helix between the two carboxylate-providing amino acids. It is most likely that K. oxytoca GspG belongs to the latter subclass and that the β-strand swap in the crystal structure (13) disrupted the calcium-binding site.

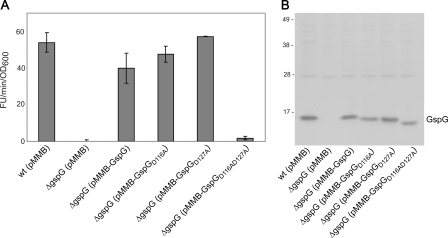

The functional importance of Ca2+ coordination by GspG was assessed by replacing the highly conserved residues Asp-116 and Asp-127 in V. cholerae GspG with alanines and monitoring the effect on extracellular secretion of protease by V. cholerae. No protease secretion was observed when plasmid-encoded GspG-D116A/D127A was expressed in a mutant strain lacking GspG (Fig. 3), indicating that the simultaneous removal of the two aspartate carboxylates prevents T2SS function by impairing Ca2+ binding. The singly substituted variants, GspG-D116A and GspG-D127A, remained functional (Fig. 3A), presumably because either carboxylate in conjunction with the main chain carbonyls from Leu-113, Gln-118, Gly-120, and Gly-125 is still capable of Ca2+ binding. Immunoblot analysis of cell extracts from the ΔgspG mutant strain showed that the single and the double mutant variant proteins were expressed at levels similar to that of wild-type GspG (Fig. 2A). We also measured thermal stability of the wild-type and the double D116A/D127A mutant GspG using a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay (34, 38, 39) and found that the mutant is slightly less stable than wild-type GspG, with a Tm of 46.4 °C versus 50.0 °C. Interestingly, the stability of the double mutant was unaffected by adding Ca2+ or EDTA, whereas the stability of the wild-type protein increased substantially upon adding Ca2+ (Tm 56.2 °C) and decreased upon adding EDTA (Tm 40.1 °C).

FIGURE 3.

Simultaneous substitution of Asp-116 and Asp-127 results in V. cholerae GspG inactivation. A, wild-type (wt) and gspG mutant strains of V. cholerae containing either pMMB67 or pMMB-gspG variants were grown in LB. Culture supernatants were tested for the presence of extracellular protease. The rate of hydrolysis was obtained from three independent experiments, and the results are presented with standard error (±S.E.). FU, fluorescence units. B, cells were disrupted and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-GspG antibodies to determine the relative level of V. cholerae GspG expression. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left, and V. cholerae GspG variants are shown on the right.

These studies clearly indicate that altering the coordinating aspartates of the Ca2+ site in V. cholerae GspG dramatically impairs the functioning of the T2SS. The loss of calcium binding by GspG could influence protein secretion by the T2SS in a number of ways, for instance by possibly promoting a conformation of the C-terminal helix conducive for favorable interactions in the pseudopilus (supplemental Fig. 3).

It appears that three major fibrous arrangements used by bacterial secretion systems are dependent on entirely different stabilizing features: disulfide bridges in the type 4 pilins (21), isopeptide bonds in the thin fibers of Gram-positive bacteria (23), and calcium ions in the pseudopilus of the T2SS (Figs. 1 and 2). Intriguingly, an unrelated dinuclear calcium site is observed and conserved in the tip pseudopilin GspK (17). Hence, the T2SS is dependent on calcium binding in multiple ways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Moseley from the Department of Microbiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, for providing the EHEC genomic DNA; Michael Bagdasarian, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, for the anti-EpsG antiserum; and the SSRL for x-rays.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI34501 (to W. G. J. H.) and AI49294 (to M. S.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3FU1, 3GN9, and 3G20) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1 and supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- T2SS

- type 2 secretion system

- EHEC

- enterohemorrhagic E. coli

- Eps

- extracellular protein secretion

- Gsp

- general secretory pathway

- ASU

- asymmetric unit

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- Bis-Tris

- 2-(bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid

- TLS

- translation/libration/ screw.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cianciotto N. P. (2005) Trends Microbiol. 13, 581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pugsley A. P., Possot O. (1993) Mol. Microbiol. 10, 665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandkvist M., Michel L. O., Hough L. P., Morales V. M., Bagdasarian M., Koomey M., DiRita V. J., Bagdasarian M. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 6994–7003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson T. L., Abendroth J., Hol W. G., Sandkvist M. (2006) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255, 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filloux A. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 163–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peabody C. R., Chung Y. J., Yen M. R., Vidal-Ingigliardi D., Pugsley A. P., Saier M. H., Jr. (2003) Microbiology 149, 3051–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keizer D. W., Slupsky C. M., Kalisiak M., Campbell A. P., Crump M. P., Sastry P. A., Hazes B., Irvin R. T., Sykes B. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24186–24193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandkvist M. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 3523–3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauvonnet N., Vignon G., Pugsley A. P., Gounon P. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 2221–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunn D. N., Lory S. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 3281–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunn D. N., Lory S. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 4375–4382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandkvist M. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 40, 271–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Köhler R., Schäfer K., Müller S., Vignon G., Diederichs K., Philippsen A., Ringler P., Pugsley A. P., Engel A., Welte W. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 54, 647–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand E., Bernadac A., Ball G., Lazdunski A., Sturgis J. N., Filloux A. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 2749–2758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanez M. E., Korotkov K. V., Abendroth J., Hol W. G. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 375, 471–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanez M. E., Korotkov K. V., Abendroth J., Hol W. G. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 377, 91–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korotkov K. V., Hol W. G. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parge H. E., Forest K. T., Hickey M. J., Christensen D. A., Getzoff E. D., Tainer J. A. (1995) Nature 378, 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig L., Pique M. E., Tainer J. A. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 363–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig L., Volkmann N., Arvai A. S., Pique M. E., Yeager M., Egelman E. H., Tainer J. A. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen J. K., Forest K. T. (2006) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 11, 192–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunn D. (1999) Trends Cell Biol. 9, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang H. J., Coulibaly F., Clow F., Proft T., Baker E. N. (2007) Science 318, 1625–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terwilliger T. (2004) J Synchrotron Radiat. 11, 49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheldrick G. M. (2008) Acta Crystallogr. A 64, 112–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrakis A., Harkiolaki M., Wilson K. S., Lamzin V. S. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 1445–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabsch W. (1993) J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Painter J., Merritt E. A. (2006) Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62, 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sikora A. E., Lybarger S. R., Sandkvist M. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 8484–8495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo M. C., Aulabaugh A., Jin G., Cowling R., Bard J., Malamas M., Ellestad G. (2004) Anal. Biochem. 332, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chenna R., Sugawara H., Koike T., Lopez R., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G., Thompson J. D. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouet P., Robert X., Courcelle E. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3320–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matulis D., Kranz J. K., Salemme F. R., Todd M. J. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 5258–5266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pantoliano M. W., Petrella E. C., Kwasnoski J. D., Lobanov V. S., Myslik J., Graf E., Carver T., Asel E., Springer B. A., Lane P., Salemme F. R. (2001) J. Biomol. Screen. 6, 429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.