Abstract

YafO is a toxin encoded by the yafN-yafO antitoxin-toxin operon in the Escherichia coli genome. Our results show that YafO inhibits protein synthesis but not DNA or RNA synthesis. The in vivo [35S]methionine incorporation was inhibited within 5 min after YafO induction. In in vivo primer extension experiments with two different mRNAs, the specific cleavage bands appeared 11–13 bases downstream of the initiation codon, AUG, 2.5 min after the induction of YafO. An identical band was also detected in in vitro toeprinting experiments when YafO was added to the reaction mixture containing 70 S ribosomes and the same mRNAs even in the absence of tRNAfMet. Notably, this band was not detected in the presence of YafO alone, indicating that YafO by itself does not have endoribonuclease activity under the conditions used. The full-length mRNAs almost completely disappeared 30 min after YafO induction in in vivo primer extension experiments, consistent with Northern blotting analysis. Over 84% of [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was released from the translation initiation complex at 5.43 μm YafO in vitro. We demonstrated that the 70 S ribosome peak significantly increased upon YafO induction, and when the 70 S ribosomes dissociated into 50 and 30 S subunits, YafO was found to be associated with 50 S subunits. These results demonstrate that YafO is a ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase inhibiting protein synthesis.

YafO is one of the toxins (1) encoded by the Escherichia coli genome. It is co-expressed with YafN, its cognate antitoxin. It has been shown that dinB, yafN, yafO, and yafP are present in the same operon (2). Under UV irradiation, the transcription level of YafO exhibits a 4-fold increase (3), suggesting that YafO may be involved in an SOS reaction.

MazF and RelE are extensively studied toxin-antitoxin toxins in E. coli. Interestingly, RelE by itself has no endoribonuclease activity (4) and has been demonstrated to be a ribosome-associated factor that stimulates the endogenous ribonuclease activity of ribosomes (5). On the other hand, MazF is a ribosome-independent endoribonuclease that cleaves mRNAs specifically at ACA sequences and is thus termed an mRNA interferase (6). ChpBK encoded by the E. coli genome was also found to be another mRNA interferase specifically cleaving mRNAs at UAC sequences (7). YoeB was found to be a ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase. It binds to the 50 S ribosomal subunit in 70 S ribosomes interacting with the A site leading to mRNA cleavage. As a result, translation initiation is effectively inhibited (8).

In the present paper, we demonstrate that YafO is also a 50 S ribosome-associated mRNA interferase that inhibits protein synthesis. The in vivo primer extension experiments with two different mRNAs revealed a major cleavage band 11–13 bases downstream of the initiation codon 2.5 min after YafO induction. An identical band was also detected in in vitro toeprinting experiments when YafO was added to the reaction mixtures containing 70 S ribosomes and the same mRNAs even in the absence of initiator tRNAfMet. Notably these cleavage bands were not observed when YafO was incubated with mRNA in the absence of ribosomes. It should be noted that a nonsense mutation in the second codon did not significantly affect YafO-mediated ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase activity. Over 84% of [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was released from the translation initiation complex at 5.43 μm YafO in vitro. These results indicate that YafO associates with 50 S subunits in 70 S ribosomes to effectively inhibit protein synthesis by cleaving mRNAs 11–13 bases downstream of the initiation codon. Thus, YafO is a ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase inhibiting protein synthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

E. coli BL21(DE3), BW25113 (ΔaraBAD) (9), and MRE600 (10) were used. The yafN-yafO operon was amplified by PCR using E. coli genomic DNA as template and cloned into the NdeI-XhoI sites of pET21c (Novagen). This construction created an in-frame translation fusion with a His6 tag at the yafO C-terminal end. The plasmid was designated as pET21c-YafN-YafO-His6. The yafO gene was cloned into both pBAD30 and pBAD33, creating pBAD30-YafO and pBAD33-YafO, respectively, to tightly regulate yafO expression by the addition of arabinose (0.2%). The ompA gene fragment was cloned into pBAD30, creating pBAD30-ompA. The yafN gene was cloned into pCold-TF (Trigger factor) (Takara) creating pCold-TF-YafN.

Assay of Protein, DNA, and RNA Synthesis in Toluene-treated Cells

A 70-ml culture of E. coli BW25113 containing the pBAD30-YafO plasmid was grown at 37 °C in M9 medium with 0.5% glycerol (no glucose) and all the amino acids except for methionine and cysteine (1 mm each). When the A600 of the culture reached 0.4, arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. After incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, the cells were treated with 1% toluene (11, 12). Using toluene-treated cells, protein synthesis was carried out with [35S]methionine as described previously (11, 12). The toluene-treated cells were washed once with 0.05 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature, then resuspended into the same buffer to examine DNA synthesis using [α-32P]dCTP as described previously (13). For assaying RNA synthesis, the toluene-treated cells were washed once with 0.05 m Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) at room temperature and then resuspended into the same buffer to measure [α-32P]UTP incorporation into RNA as described previously (14, 15).

Assay of in Vivo Protein Synthesis

E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO were grown in M9 medium with 0.5% glycerol (no glucose) and all the amino acids except for methionine and cysteine (1 mm each). When the A600 value of the culture reached 0.4, arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2% to induce YafO expression. Cell cultures (0.6 ml) were taken at the time intervals indicated in Fig. 1F and mixed with 30 μCi of [35S]methionine. After 1 min of incubation at 37 °C, the rate of protein synthesis was determined as described previously (6). For SDS-PAGE analysis of the total cellular protein synthesis, the samples were removed from the [35S]methionine incorporation reaction mixture (500 μl) at the time intervals indicated in Fig. 1F and added into chilled test tubes containing 100 μg/ml each of nonradioactive methionine and cysteine. The cell pellets collected by centrifugation were dissolved into 50 μl of loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of YafO on protein, DNA, and RNA synthesis. A, effect of YafO on [35S]methionine incorporation in toluene-treated cells. E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO were grown at 37 °C in glycerol-M9 medium. When the A600 of the culture reached 0.4, arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. After incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, the cells were treated with toluene (11, 12). Using toluene-treated cells, ATP-dependent protein synthesis was carried out with [35S]methionine as described previously (11). B, effect of YafO on [α-32P]dCTP incorporation in toluene-treated cells (13). C, effect of YafO on [α-32P]UTP incorporation in toluene-treated cells (14). D, growth curve of BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO plasmid in the LB medium. Arabinose was added at 150 min as indicated by a solid arrow. E, effect of YafO on [35S]methionine incorporation in vivo. [35S]Methionine incorporation into E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO was measured at various time points after YafO induction as indicated. F, SDS-PAGE analysis of in vivo protein synthesis after the induction of YafO. The same cultures as those in E were used.

Purification of YafO-His6 and TF-YafN Proteins

YafO-His6-tagged at the C-terminal end was purified from strain BL21(DE3) carrying pET-21c-YafN-YafO. The cell pellets were dissolved in 6 m guanidine-HCl. Denatured YafO-His6 was first trapped on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin and then refolded by step-by-step dialysis. TF-YafN tagged at the N-terminal end was purified from strain BL21(DE3) carrying pCold-TF-YafN with the use of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen).

Effect of YafO on Protein Synthesis in Prokaryotic Cell-free Systems

Prokaryotic cell-free protein synthesis was carried out with an E. coli T7 S30 extract system (Promega). The reaction mixture consisted of 10 μl of S30 premix, 7.5 μl of S30 extract, and 2.5 μl of an amino acid mixture (1 mm each of all amino acids except methionine), 1 μl of [35S]methionine, and different amounts of YafO-His6 and TF-YafN in a final volume of 29 μl. The different amounts of YafO-His6 and TF-YafN were preincubated for 10 min at 25 °C before the assay was started by adding 1 μl of pET-11a-MazG plasmid-DNA (0.16 μg/μl) (16). The reaction was performed for 1.5 h at 37 °C, and the proteins were then precipitated with acetone and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Preparation of E. coli 70 S Ribosomes

70 S ribosomes were prepared from E. coli MRE 600 as described previously (17–19) with minor modification. Bacterial cells (2 g) were suspended in buffer A (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, containing 10 mm MgCl2, 60 mm NH4Cl, and 6 mm 2-mercaptoethanol). The cells were lysed by French Press. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation two times at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C with a Beckman 50Ti rotor. The supernatant (three-fourths volume from the top) was then layered over an equal volume of 1.1 m sucrose in buffer B (buffer A containing 0.5 m NH4Cl) and centrifuged at 45,000 rpm for 15 h at 4 °C with a Beckman 50Ti rotor. After washing with buffer A, the ribosome pellets were resuspended in buffer A and applied to a linear 5–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient prepared in buffer A and centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 3 h at 4 °C with a Beckman SW41Ti rotor. The gradients were fractionated, and the 70 S ribosome fractions were pooled and pelleted at 45,000 rpm for 20 h at 4 °C with a Beckman 50Ti rotor. The 70 S ribosome pellets were then resuspended in buffer A and stored at −80 °C.

Ribosome Profile Analysis

For polysome profile analysis, the cells containing the pBAD30-YafO plasmid were grown at 37 °C in 150 ml of LB medium, and at an A600 of 0.6, arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. After 10 min of induction, chloramphenicol was added to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. The extracts were prepared using liquid nitrogen, freezing, and thawing four times. Approximately 10 A260 units of the lysate were layered onto a 5–40% sucrose gradient in buffer A (10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.8, 60 mm NH4Cl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol) and centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 3 h at 4 °C in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor. The gradients were analyzed with continuous monitoring at 254 nm. To analyze a 50 and 30 S ribosome profile, another 10 A260 units of lysates as prepared above were dialyzed overnight against buffer B (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 60 mm NH4Cl, 0.5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol) (dialysis buffer was changed once), layered onto 5–40% sucrose gradients in buffer B (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 60 mm NH4Cl, 0.5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol), and then centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 3 h at 4 °C in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor. The gradients were analyzed with continuous monitoring at 254 nm.

Primer Extension Analysis in Vivo

For primer extension analysis of mRNA cleavage sites in vivo, total RNAs were extracted from the E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO at different time points as indicated in the legend to Fig. 4. Primer extension was carried out using different primers as described previously (6).

FIGURE 4.

In vivo identification of YafO cleavage sites in the chromosomally encoded ompA and ompF mRNAs. The ompA and ompF mRNAs were prepared from E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO at various time points as indicated before and after the induction of YafO. The sequence ladders for ompA and ompF were obtained using pCR®2.1-TOPO®-ompA and pCR®2.1-TOPO®-ompF as template, respectively. The sequences around the major cleavage sites are shown to the right, and the major primer extension stop sites are indicated by the arrowheads. A, primer extension analysis of the ompA mRNA. B, primer extension analysis of the ompF mRNA.

Toeprinting Assays

Toeprinting was carried out as described previously (20) with a minor modification. The mixture for primer-template annealing containing mRNA and 32P end-labeled DNA primer was incubated at 70 °C for 5 min and then cooled slowly to room temperature. The ribosome-binding mixture contained 2 μl of 10× buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, containing 100 mm MgCl2, 600 mm NH4Cl, and 60 mm 2-mercaptoethanol), different amounts of YafO-His6, 0.375 mm dNTP, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomal subunits, 1 μm tRNAfMet, and 2 μl of the annealing mixture in a final volume of 20 μl. The final mRNA concentration was 0.035 μm. This ribosome-binding mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and then reverse transcriptase (2 units) was added. The cDNA synthesis was carried out at 37 °C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 12 μl of the sequencing loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mm EDTA, 0.05% bromphenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol EF). The sample was incubated at 90 °C for 5 min prior to electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The ompA and ompF mRNAs were synthesized in vitro from their individual DNA fragments, each containing a T7 promoter and a part of their opening reading frames, using T7 RNA polymerase. These approximate 200-bp DNA fragments for ompA (248 bp) and ompF (224 bp), both of which had the initiation codon at the center, were amplified by PCR using appropriate primers with chromosome DNA as templates. The 5′-end primers for ompA and ompF contained the T7 promoter sequence.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis

E. coli BW25113 containing pBAD30-YafO was grown at 37 °C in LB medium. When the A600 value reached 0.6, arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. The samples were taken at different intervals as indicated in Fig. 3. Total RNAs were isolated using the hot phenol method as described previously (21). Northern blot analysis was carried out as described previously (22).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of YafO on cellular mRNAs in vivo. A, total cellular RNAs were extracted from E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD30-YafO at various time points as indicated after the addition of arabinose and subjected to Northern blot analysis using radiolabeled ompA and ompF open reading frame as probes. B, the same total cellular RNA in A was analyzed by 1% native agarose gel followed by ethidium bromide staining.

Binding of [35S]Methionine-tRNAfMet to the mRNA-70 S Ribosome Complex

The reactions were carried out with the ompA mRNA that was used for the toeprinting experiments. The reaction buffer used was buffer A (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 10 mm MgCl2, 60 mm NH4Cl, and 6 mm β-mercaptoethanol). 70 S ribosomes (1 pmol) were first incubated with the ompA mRNA (0.7 pmol) and [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet (40 pmol) for 10 min at 37 °C, and then different amounts of YafO were added in a final reaction volume of 20 μl. The samples were incubated for an additional 10 min at 37 °C. The reaction mixtures were applied to nitrocellulose filters (Millpore; 0.45 μm hemagglutinin), which were washed twice with 2 ml of buffer A before measuring the radioactivity. [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was synthesized in a buffer containing 30 mm Hepes, pH 7.6, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 3 mm ATP, 5 mm Mg(OAc)2, 30 mm KOAc, 350 μCi of [35S]methionine, and 62.3 μm tRNAfMet (Sigma) using aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (Sigma).

RESULTS

YafO Inhibits Protein Synthesis Immediately after Its Induction

To identify the cellular function(s) inhibited by YafO, a cell-free system was prepared from E. coli BW25113 cells carrying the arabinose-inducible pBAD30-YafO vector. The cells were permeabilized by toluene treatment (11, 12). ATP-dependent [35S]methionine incorporation was completely inhibited when cells were preincubated for 10 min in the presence of arabinose before toluene treatment (Fig. 1A), whereas the incorporation of [α-32P]dCTP (Fig. 1B) and [α-32P]UTP (Fig. 1C) was not significantly affected under similar conditions (13, 14). These results demonstrate that YafO inhibits protein synthesis, but not DNA replication or RNA synthesis. Notably, cell growth was completely inhibited almost immediately after the addition of arabinose (Fig. 1D). The in vivo incorporation of [35S]methionine was also almost completely inhibited within 5 min after YafO induction (Fig. 1, E and F).

Inhibitory Effect of Purified YafO on Cell-free Protein Synthesis

Next, we examined the effect of purified YafO on E. coli cell-free protein synthesis. YafO-His6 was purified from cells co-expressing both YafN and YafO-His6 as described under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 2A). The synthesis of MazG protein (30 kDa) (16) from plasmid pET-11a-MazG was tested at 37 °C for 1 h in the absence and the presence of YafO-His6 using an E. coli T7 S30 extract system (Promega) (Fig. 2B). MazG synthesis was almost completely blocked at a YafO-His6 concentration of 8.0 μm.

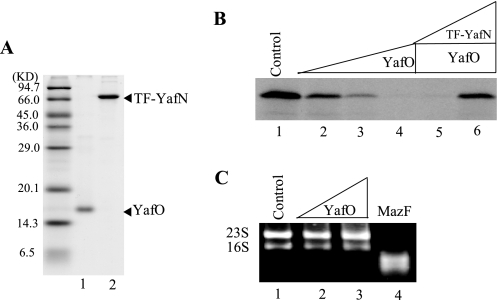

FIGURE 2.

Effect of purified YafO-His6 on cell-free protein synthesis. A, purification of YafO-His6 and TF-YafN. Lane 1, purified YafO-His6; lane 2, purified TF-YafN. B, effect of YafO-His6 on MazG synthesis in a prokaryotic cell-free protein synthesis using E. coli T7 S30 extract system (Promega) and pET-11a-MazG as a template. Lane 1, without YafO-His6; lanes 2–4, 0.5, 2.0, and 8.0 μm YafO-His6 added, respectively; lanes 5 and 6, 8.0 μm YafO-His6 added with TF-YafN in the ratio to YafO-His6 of 0.46 and 1.73 respectively. C, effect of YafO-His6 and MazF-His6 on RNA stability. Total RNAs were mixed with different amount of protein and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. The reaction products were analyzed by 1% agarose native gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining. Lane 1, no protein was added; lane 2, 6.0 μm YafO-His6 was added; land 3, 15 μm YafO-His6 was added; lane 4, 0.08 μm MazF-His6 was added.

We next tested the effect of YafN antitoxin on the YafO-mediated inhibition of MazG synthesis. YafN was purified as a fusion protein with trigger factor (TF)2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The addition of TF-YafN rescued MazG synthesis (Fig. 2B, lane 6). Importantly, YafO-His6 (Fig. 2C, lanes 2 and 3) did not cleave RNA by itself in contrast to MazF-His6 (Fig. 2C, lane 4), which is a known ribosome-independent endoribonuclease that cleaves mRNAs specifically at ACA sequences (6).

YafO Induction Causes Cleavage of Cellular mRNAs

The induction of YafO significantly reduced the stability of cellular mRNAs because the full-length ompA and ompF mRNAs very quickly disappeared within 10 min after YafO induction (Fig. 3A). It should be noted that the 23 and 16 S rRNA were stable even 30 min after YafO induction (Fig. 3B).

As shown above, cellular mRNAs were degraded upon induction of YafO. Therefore we attempted to identify the cleavage sites of the chromosomally encoded ompA and ompF mRNAs by primer extension experiments. For this purpose, total RNAs were extracted from E. coli BW25113 cells harboring pBAD30-YafO at different time intervals after the induction of YafO. The primer extension analyses of ompA (Fig. 4A) and ompF mRNAs (Fig. 4B) demonstrated that the distinct major bands corresponding to the specific cleavage sites in each mRNA appeared 2.5 min after YafO induction (Fig. 4, A and B, lanes 2). The band intensities for ompA (Fig. 4A) further increased from 2.5 to 20 min after YafO induction. Interestingly, in both cases, the major bands resulted from the cleavage of the mRNAs downstream of AUG. Most notably, no other bands were observed in the 5′-untranslated region, suggesting that YafO may function only when it associates with the ribosomal translation machine. It is interesting to note that the amount of the full-length ompA and ompF mRNAs gradually decreased (Fig. 4, A and B), consistent with the Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3A).

YafO Binds to the Translation Initiation Complex in Vitro

Next, we examined whether similar cleavage sites of ompA and ompF mRNAs are observed in vitro by the toeprinting (TP) experiments using YoeB as a control (20). Primer extension analysis of the mRNAs alone yielded the full-length bands (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 1). The addition of YafO or YoeB alone did not result in the formation of new bands, indicating that YafO or YoeB by itself has no endoribonuclease activity under the condition used (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). When 70 S ribosomes and initiator tRNAfMet were added to the reaction mixtures, a typical toeprinting band TP(r) downstream of the initiation codon appeared (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 10, as indicated by black dots). On the other hand, when either YafO-His6 or YoeB was added together with 70 S ribosomes and initiator tRNAfMet, a new band, TP(O) (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 12, shown by an asterisk) or TP(Y) (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 11), appeared in both cases. Notably, the TP(Y) band is identical to that with YoeB (8). TP(O) was formed one base downstream of TP(r). It should be noted that both the TP(O) and TP(r) bands were observed only in the presence of 70 S ribosomes and initiator tRNAfMet (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 12 and 10). Note that the TP(O) band originated as a result of mRNA cleavage and not toeprinting as described below.

FIGURE 5.

Toeprinting of the ompA and ompF mRNAs. A, toeprinting of the ompA mRNA in the presence of YafO-His6. The mRNA was synthesized in vitro from a 248-bp DNA fragment containing a T7 promoter using T7 RNA polymerase as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The sequence ladder shown to the right was obtained using the same primer used for toeprinting with pCR®2.1-TOPO®-ompA as template. B, toeprinting of the ompF mRNA in the presence of YafO-His6. The mRNA was synthesized in vitro from a 224-bp DNA fragment containing a T7 promoter using T7 RNA polymerase as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The sequence ladder shown to the right was obtained using the same primer used for toeprinting with pCR®2.1-TOPO®-ompF as template. Lane 1, control; lane 2, with 0.34 μm YoeB-His6; lane 3, with 12.3 μm YafO-His6; lane 4, 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 5, 0.34 μm YoeB-His6 and 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 6, 12.3 μm YafO-His6 and 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 7, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes; lane 8, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 0.34 μm YoeB-His6; lane 9, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 12.3 μm YafO-His6; lane 10, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 11, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 1 μm tRNAfMet with 0.34 μm YoeB-His6; lane 12, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 1 μm tRNAfMet with 12.3 μm YafO-His6. Both mRNA sequences shown are complementary to the sequencing ladders. The initiation codon, AUG, is indicated with an arrow. SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence. TP(O) is the band where toeprinting was stopped in the presence of YafO-His6 (shown by an asterisks). TP(Y) is the band where toeprinting was stopped in the presence of YoeB-His6. FL, the full-length of the mRNA; TP(r), the toeprinting site caused by normal ribosome binding to mRNA in the absence of YafO (indicated by black dots).

Next, we tested whether the TP(O) and TP(r) bands resulted from the cleavage of mRNAs using ompA and ompF mRNAs. These mRNAs were first preincubated without (Fig. 6, A and B, lanes 5) or with YafO (Fig. 6, A and B, lanes 7) in the presence of 70 S ribosomes and initiator tRNAfMet. RNAs were then phenol-extracted and used for primer extension as shown in Fig. 6 (A and B, lanes 6 and 8). The TP(O) band was still observed after phenol extraction together with the full-length mRNAs (compare lanes 7 and 8 in Fig. 6, A and B, shown by asterisks), indicating that the TP(O) band resulted from at least partial cleavage of the ompA and ompF mRNAs. In contrast, the TP(r) band disappeared after phenol extraction (compare lanes 5 and 6 in Fig. 6, A and B, shown by black dots), indicating that this band was not due to mRNA cleavage but was caused by ribosome binding. It is important to note that the mRNAs were cleaved downstream of the translation initiation codon only in the presence of ribosomes, initiator tRNAfMet, and YafO, but not in the presence of YafO alone.

FIGURE 6.

Toeprinting of the ompA and ompF mRNAs after phenol extraction. A, primer extension analysis of the ompA mRNA after phenol extraction. The experiment was carried out in the same way as described for Fig. 5A except that reaction products in lanes 4, 6, and 8 were phenol-extracted to remove proteins before primer extension. B, toeprinting of the ompF mRNA after phenol extraction. The experiment was carried out in the same way as described for Fig. 5B except that reaction products in lanes 4, 6, and 8 were phenol-extracted to remove proteins before primer extension. Lane 1, without YafO-His6; lane 2, 12.3 μm YafO-His6; lane 3, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes with 12.3 μMYafO-His6; lane 4, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes with 12.3 μm YafO-His6; lane 5, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes with 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 6, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes with 1 μm tRNAfMet; lane 7, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes, 1 μm tRNAfMet with 12.3 μm YafO-His6; lane 8, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes, 1 μm tRNAfMet with 12.3 μm YafO-His6.

tRNAfMet Is Not Required for YafO-mediated mRNA Cleavage

Next we examined whether the initiator tRNAfMet is required for binding of mRNA to 70 S ribosomes in the presence of YafO. Intriguingly, the ompA and ompF mRNAs were able to bind to 70 S ribosomes even in the absence of tRNAfMet if YafO was included in the reaction, yielding identical toeprinting bands (compare lanes 9 with 10 in Fig. 5, A and B). Importantly, these TP(O) bands produced in the absence of tRNAfMet were also due to mRNA cleavage (compare lanes 3 with lanes 4 in Fig. 6, A and B). It should be noted that in the absence of YafO, the addition of tRNAfMet was required for the stable binding of the ompA and ompF mRNAs to 70 S ribosomes (compare lanes 10 with lanes 7 in Fig. 5, A and B; the toeprinting in lane 10 was carried out in the presence of tRNAfMet, whereas that in lane 7 was performed in the absence of tRNAfMet). The addition of YafO alone (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 3), tRNAfMet alone (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 4), or YafO plus tRNAfMet (Fig. 5, A and B, lanes 6) did not yield any toeprinting bands either at the TP(O) or at the TP(r) position. These results suggest that YafO-mediated mRNA cleavage does not require RNAfMet, which is similar to YoeB (compare lanes 7 with lanes 8 in Fig. 5).

[35S]Methionine-labeled tRNAfMet ([35S]Methionine-tRNAfMet) Is Released from Ribosomes When YafO Is Added

To examine whether the translation initiation complex is stable after YafO is added, we carried out an experiment to examine whether [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet is released from ribosomes when YafO is added. [35S]Methionine-tRNAfMet was synthesized and used for its complex formation with 70 S ribosomes and mRNA in the presence and the absence of YafO under the same condition used for the toeprinting experiment in Fig. 5A. As shown in Fig. 7A, because the amount of YafO added in the reaction mixture was reduced (from lane 3 to lane 11), the intensity of TP(O) bands are progressively reduced, whereas the intensity of the full-length bands increased gradually. It should be noted even though the TP(O) band (Fig. 7A, lane 3 indicated by an asterisk) is in the identical position to the TP(r) band (Fig. 7A, lane 2, indicated by a black dot), the TP(O) band is produced by mRNA cleavage (Fig. 7B, lane 6), whereas the TP(r) band is due to ribosome binding to mRNA (Fig. 7B, lane 4).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of YafO on the stability of translation initiation complex. A, effect of YafO on the formation of the ompA mRNA-70 S Ribosome-tRNAfMet complex. Lane 1, without YafO-His6; lane 2, 1 μm tRNAfMet and 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes; lanes 3–11, 1 μm tRNAfMet and 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes and 5.43, 2.72, 1.36, 0.68, 0.34, 0.17, 0.085, 0.0425, and 0.021 μm YafO-His6, respectively. B, primer extension analysis of the ompA mRNA after phenol extraction. The experiment was carried out in the same way as described for Fig. 7A except that reaction products in lanes 4 and 6 were phenol-extracted to remove proteins before primer extension. Lane 1, without YafO-His6; lane 2, 1.36 μm YafO-His6; lane 3, 1 μm tRNAfMet and 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes; lane 4, 1 μm tRNAfMet and 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes; lane 5, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes, 1 μm tRNAfMet with 1.36 μm YafO-His6; lane 6, 0.05 μm 70 S ribosomes, 1 μm tRNAfMet with 1.36 μm YafO-His6. C, binding of [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet to 70 S ribosomes at 37 °C in the absence and the presence of different amounts of YafO-His6. 70 S ribosomes (0.05 μm) were first incubated with [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet (1 μm) and the ompA mRNA (0.035 μm) for 10 min at 37 °C then 0, 0.021, 0.0425, 0.085, 0.34, 0.68, 1.36, 2.72, or 5.43 μm YafO was added. The reaction mixtures were incubated for additional 10 min at 37 °C and then applied to nitrocellulose filters (Millpore; 0.45 μm hemagglutinin), which were washed twice with 2 ml of buffer A before measuring the radioactivity.

Next, we tested whether tRNAfMet bound to the ribosomes is displaced with YafO under the same condition used in Fig. 7A. For this purpose, [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was first incubated with 70 S ribosomes and mRNA at 37 °C for 10 min, and then different amounts of YafO were added as in Fig. 7A. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for another 10 min and then applied to nitrocellulose filters (Millpore; 0.45 μm hemagglutinin). The filters were washed twice with 2 ml of buffer A before measuring the radioactivity that was retained on the filters. As shown in Fig. 7C, [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was displaced in a YafO concentration-dependent manner. Over 84% of [35S]methionine-tRNAfMet was released at 5.43 μm YafO (the ratio of YafO to used ribosome was 100:1). This result suggests that the translation initiation complex is not stable after YafO is added. It should be noted that the stability of binding of initiator tRNA to 70 S ribosomes is known to be coupled to that of mRNA. Therefore if mRNA is cleaved, the binding of mRNA to 70 S ribosomes should be reduced, which in turn likely destabilizes initiator tRNA binding (8).

Inability to Form the First Peptide Bond Does Not Affect YafO-mediated Ribosome-dependent mRNA Interferase Activity

To examine whether the first peptide bond formation is required for YafO-mediated mRNA cleavage activity, we created a nonsense mutation on the second codon on the ompA gene. The wild-type or mutated pBAD30-ompA plasmids (Fig. 8) were then co-transformed with pBAD33-YafO into ΔompA BW25113 cells. Total RNAs were extracted at different time points as shown in Fig. 8 (B and C) after ompA and yafO were induced by the addition of 0.2% arabinose. An in vivo primer extension experiment was carried out using the same primer used in Fig. 4A. As shown in Fig. 8 (B and C), the cleavage pattern of the wild-type ompA mRNA was identical to that of the mutant ompA mRNA containing the nonsense mutation, indicating that the inability to form the first peptide bond does not affect YafO-mediated ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase activity. It should be noted that the cleavage band did not appear when YafO was not induced (Fig. 8B, lane 1). It appears that the mRNA interferase activity is weaker in the mRNA carrying the nonsense mutation than that in wild-type ompA mRNA (Fig. 8, compare B with C). This may be due to the weaker affinity of ribosomes to mRNA with nonsense mutations. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism.

FIGURE 8.

Inability to form the first peptide does not completely inhibit YafO-mediated mRNA cleavage activity. The wild-type ompA and ompA with nonsense mutation in the second codon mRNAs were prepared from ΔompA E. coli BW25113 cells containing pBAD33-YafO and pBAD30-ompA at various time points as indicated before and after the induction of YafO and OmpA. The sequence ladders for ompA were obtained using pCR®2.1-TOPO®-ompA as template, respectively. The sequences around the major cleavage sites are shown to the right, and the major primer extension stop sites are indicated by the arrowheads. A, ompA gene fragment sequence. The Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence, the initiation codon, and nonsense mutation are indicated. B, primer extension analysis of the wild-type ompA mRNA. C, primer extension analysis of the ompA mRNA with nonsense mutation in the second codon.

YafO Associates with 50 S Ribosomal Subunits

Because YafO binds to the translation initiation complex (Fig. 5), we examined whether YafO affects the polysome profiles and also whether it specifically associates with one of the ribosomal subunits. When the polysome pattern of E. coli BW25113 cells carrying the pBAD-YafO plasmid was analyzed by sucrose density gradient at 10 min after induction of YafO by arabinose, a significant increase in the 70 S ribosomal fraction was observed without a change in the 30 and 50 S ribosomal profiles (Fig. 9, compare B with A). Western blotting analysis showed that the majority of YafO was associated with both 70 S ribosome and 50 S ribosome fractions, but not with the 30 S ribosome fraction (Fig. 9B). Cell lysates were prepared in 0.5 mm Mg2+ to dissociate 70 S ribosomes to 50 and 30 S ribosomes and analyzed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (Fig. 9C). The majority of YafO was detected in the 50 S ribosome fraction, suggesting that YafO is a 50 S ribosome-associating protein. It should be noted there is essentially no free YafO in Fig. 9B, suggesting that YafO may bind more tightly to 50 and 70 S ribosomes.

FIGURE 9.

YafO associates with the 50 S ribosomal subunits. Ribosome profiles were analyzed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, polysome profiles of E. coli BW25113 containing pBAD30-YafO without YafO induction. B, polysome profiles of E. coli BW25113 containing pBAD30-YafO at 10 min after YafO induction. C, 70 S ribosomes of the same lysate used in B were disassociated into 50 and 30 S ribosomal subunits in 0.5 mm Mg2+. In B and C, Western blot analysis was carried out to detect YafO in each gradient fraction.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that YafO is a potent inhibitor of protein synthesis. Upon YafO induction, [35S]methionine incorporation into cellular proteins abruptly stopped after 5 min (Fig. 1, E and F), and the full-length cellular mRNAs rapidly disappeared (Fig. 3A).

It is important to note that to avoid artifacts we carried out in vivo primer extension experiments using chromosomally encoded mRNAs as targets rather than mRNAs encoded by genes cloned in a multi-copy plasmid. Interestingly, both the mRNAs tested (ompA and ompF) were detected either as their corresponding full-length mRNAs or as a product cleaved downstream of the initiation codon (Fig. 4). Notably, in the two mRNAs, no other cleavage bands were detected upstream of the initiation codon, suggesting that the observed cleavage for both mRNAs occurred in a ribosome-dependent manner. This ribosome-dependent mRNA cleavage is very potent because the full-length mRNAs almost completely disappeared after 5 min of YafO induction as observed in Northern blotting analysis (Fig. 3) and the in vivo primer extension experiment (Fig. 4). Importantly, this in vivo observation was consistent with the in vitro toeprinting experiments using 70 S ribosomes, tRNAfMet, purified YafO, and the same mRNAs (Fig. 5). It should be noted that although the toeprinting bands in the presence of YafO (TP(O) in lanes 9 and 12 in Fig. 5) were almost identical to those in the absence of YafO (TP(r) in Fig. 5, lane 10), TP(O) bands were formed because of the cleavage of respective mRNAs because identical bands were detected even after phenol extraction (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 8). TP(r) bands are known to be the toeprinting bands resulting from binding of ribosome to mRNA that forms the translation initiation complex (6). Therefore, this band could not be detected after phenol extraction (Fig. 6, lane 6). Because TP(O) bands are almost at the same positions as TP(r) bands, except for the downstream band in TP(O), which is one base downstream of that in TP(r), it appears that YafO binding to 50 S ribosomal subunits in the translational complex induces mRNA cleavage at the 3′-end of the mRNA region protected by the binding of 70 S ribosomes.

It is important to note that YafO alone was not able to cleave mRNAs in the toeprinting experiments (Fig. 5), and only when it was added together with 70 S ribosomes, the mRNAs were cleaved downstream of AUG. Because 70 S ribosome binding to mRNA in the formation of the translation initiation complex does not lead to mRNA cleavage (Fig. 6, lane 6), the observed mRNA cleavage is likely to be caused by the latent endoribonuclease activity of YafO, which may be induced by its binding to 50 S subunits. The induction of the latent endoribonuclease activity may be a common mechanism for some of the toxins associated with either 30 or 50 S ribosomal subunits to inhibit protein synthesis. In this respect, it is interesting to note that when RelE, another toxin for translation inhibition that has no endoribonuclease activity by itself, was induced in E. coli, ribosome-dependent mRNA cleavage was observed (4). Another E. coli toxin called YoeB, which has 19% identity to YafO, also cleaves mRNA in a ribosome-dependent manner (23) and has been shown to have a weak endoribonuclease activity (24). Recently, we have found that YoeB cleaves mRNAs immediately downstream of the initiation codon only when it is added together with the 70 S ribosomes (8). However, the mRNA cleavage pattern by YoeB is different from that of YafO. First, the full-length mRNA almost completely disappeared within 5 min after YafO induction (Figs. 3A and 4), whereas the full-length mRNAs were stable even at 30 min after YoeB induction (8). Second, YoeB mediated mRNA cleavage occurs at the A site (8), whereas YafO-mediated mRNA cleavage occurs outside of the region covered by 70 S ribosomes (Figs. 5 and 6). Third, in the region downstream of the initiation codon, which is greater than 100 bases in length, only one strong cleavage band was formed with YoeB (8), whereas a few cleavage bands were observed in the identical region with YafO (Fig. 4). It should be noted that the inability to form the first peptide does not affect YafO-mediated ribosome-dependent mRNA cleavage activity (Fig. 8). These facts indicated that even if both YoeB and YafO inhibit protein synthesis within a short period of time (Fig. 1), the mechanism of inhibition is different for each of them. It is possible that YafO may also be able to inhibit translation elongation. Further studies are needed to elucidate how this toxin inhibits protein synthesis.

It is interesting to note that bacterial toxins such as YoeB (8) and YafO, which inhibit translation by functioning as ribosome-dependent endoribonucleases, may block protein synthesis in two steps. Initially, the binding of the toxin to 70 S ribosomes inhibits translation reversibly via binding with its cognate antitoxin. However, in the second step, as the toxin binding to ribosomes is prolonged, the latent ribonuclease activity of the toxin is induced to cleave mRNAs, which results in irreversible inhibition of protein synthesis. Such a two-step inhibitory mechanism of protein synthesis may play an intricate regulatory role in cell growth under a stress condition.

It is quite intriguing that E. coli is equipped with a number of toxins to inhibit protein synthesis by different mechanisms; for example MazF (6) and ChpBK (7) function as mRNA interferases to cleave mRNAs in a ribosome-independent manner, whereas the others such as RelE, YafO, and YoeB (8) appear to be ribosome-dependent mRNA interferases inhibiting translation. Recently, we demonstrated that Doc from the phd-doc toxin-antitoxin system in P1 phage inhibits translation elongation by binding to 30 S ribosome subunits (25). The diversity of mechanisms targeting translation in E. coli toxin-antitoxin systems may be important to form an intricate toxin-antitoxin network in the cell to adapt ever-changing environmental stresses in nature. It remains to be elucidated how these toxin-antitoxin systems play physiological roles under different stress conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sangita Phadtare for the critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank Guangying Sun for assistance doing the course of experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 1RO1GM081567 (to M. I.). This work was also supported by a grant from Takara Bio Inc.

- TF

- trigger factor

- TP

- toeprinting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown J. M., Shaw K. J. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 6600–6608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenzie G. J., Magner D. B., Lee P. L., Rosenberg S. M. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 3972–3977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courcelle J., Khodursky A., Peter B., Brown P. O., Hanawalt P. C. (2001) Genetics 158, 41–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen K., Zavialov A. V., Pavlov M. Y., Elf J., Gerdes K., Ehrenberg M. (2003) Cell 112, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes C. S., Sauer R. T. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Zhang J., Hoeflich K. P., Ikura M., Qing G., Inouye M. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 913–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Zhu L., Zhang J., Inouye M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26080–26088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Inouye M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6627–6638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swaney S. M., Aoki H., Ganoza M. C., Shinabarger D. L. (1998) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 3251–3255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halegoua S., Hirashima A., Sekizawa J., Inouye M. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 69, 163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halegoua S., Hirashima A., Inouye M. (1976) J. Bacteriol. 126, 183–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moses R. E., Richardson C. C. (1970) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 67, 674–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson R. L., Radcliffe C. W., Pace N. R. (1971) J. Bacteriol. 107, 585–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billy E., Brondani V., Zhang H., Müller U., Filipowicz W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14428–14433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Inouye M. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 5323–5329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki H., Ke L., Poppe S. M., Poel T. J., Weaver E. A., Gadwood R. C., Thomas R. C., Shinabarger D. L., Ganoza M. C. (2002) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1080–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du H., Babitzke P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20494–20503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesterkamp T., Deuerling E., Bukau B. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21865–21871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll I., Bläsi U. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 1021–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarmientos P., Sylvester J. E., Contente S., Cashel M. (1983) Cell 32, 1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker K. E., Mackie G. A. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 47, 75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christensen S. K., Maenhaut-Michel G., Mine N., Gottesman S., Gerdes K., Van Melderen L. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1705–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamada K., Hanaoka F. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M., Zhang Y., Inouye M., Woychik N. A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5885–5890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]