Abstract

TBX5 is a T-box transcriptional factor required for cardiogenesis and limb development. TBX5 mutations cause Holt-Oram syndrome characterized by congenital heart defects and upper limb deformations. Here we establish a novel function for TBX5 in pre-mRNA splicing, and we show that this function is relevant to the pathogenesis of Holt-Oram syndrome, providing a novel pathogenic mechanism for the disease. Proteomics in combination with affinity purification identifies splicing factor SC35 as a candidate TBX5-associating protein. Co-immunoprecipitation and glutathione S-transferase pulldown assays confirm the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35. TBX5 can bind to RNA homopolymers (polyribonucleotides) and to the 5′-splice site, which overrides the binding of SC35 to the same RNA. Overexpression of TBX5 increases the efficiency of pre-mRNA splicing and regulates alternative splice site selection. However, co-expression of TBX5 and SC35 antagonizes each other's positive effect on splicing. The most severe TBX5 mutation, G80R, with complete penetrance of the cardiac phenotype, strongly affects pre-mRNA splicing, whereas other mutations with incomplete penetrance of the cardiac phenotype, including R237Q, do not alter the splicing activity of TBX5. This study establishes TBX5 as the first cardiac gene and the first human disease gene with dual roles in both transcriptional activation and pre-mRNA splicing.

T-box genes encode DNA-binding transcription factors that play diverse roles in organogenesis (1). In the T-box gene family, Tbx5 has been established as a gene causing Holt-Oram syndrome, which is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by congenital heart defects and upper limb abnormalities (2, 3). All Holt-Oram patients exhibit some degree of malformations of the arms and hands, whereas ∼75% of patients have some cardiac abnormality (4). To date, many mutations in TBX5 have been identified in families or patients with Holt-Oram syndrome (5, 6). Genotype-phenotype analysis has revealed high inter- and intra-familial variability of phenotypic expressivity (4, 5). Functional significance of missense mutations on transcriptional activity of TBX5 has been investigated in detail by our group for DNA binding, transcriptional activation, nuclear localization, and protein-protein interactions (5, 7). But the poor genotype-phenotype correlation issue remains largely unexplained.

Pre-mRNA splicing is critical in the regulation of gene expression and is carried out by a large ribonucleoprotein complex called the spliceosome, which includes the five major snRNPs,2 U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 (8). In addition, there is a group of essential non-snRNP splicing factors, known as the SR (serine/arginine) family of splicing factors, that play multiple roles in splicing and have the unusual property of functioning as essential factors in constitutive splicing and as regulators of alternative splicing (9, 10). The SR proteins are highly conserved throughout metazoa and contain one or two N-terminal RNP-type RNA recognition motifs as well as a C-terminal signature motif region that consists largely of multiple Arg/Ser dipeptide repeats (RS domain) involved in protein-protein interactions (10). SC35 is a prototype of an expanding list of SR proteins and has been shown to be an essential splicing factor involved in spliceosome assembly in constitutive splicing and as a regulator of alternative splicing (9, 11). SC35 has been shown to specifically bind to mRNA sequences via the independent RNA recognition motif (12). SC35 is expressed in most tissues examined and exhibits structural similarities to the more intensely studied alternative splicing factor ASF/SF2 (13).

Regulation of transcription and RNA processing is complex, and increasing evidence suggests that transcription and splicing may be coordinated through the action of several proteins (14, 15). The three transcriptional co-activators NcoA62/SKIP, p52, and PGC-1 have been reported to be involved in both transcriptional regulation and pre-mRNA splicing (16–18); however, no typical DNA-binding transcription factors have yet been reported for coordinating both pre-mRNA splicing and transcriptional activation. We report here that transcriptional factor TBX5 can form a complex with splicing factor SC35 and plays an important role in constitutive pre-mRNA splicing, alternative splicing, and transcriptional activation. We further show that TBX5-associated splicing is relevant to the pathogenesis of Holt-Oram syndrome. This is the first demonstration of a cardiac transcription factor or a human disease gene that plays a dual role in both transcriptional activation and pre-mRNA splicing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, Transfection, and Antibodies

The full-length human Tbx5 cDNA and human SC35 cDNA were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 to create expression constructs for both proteins. Three forms of Tbx5 expression constructs were created as follows: one with and the other without the His6 epitope tag, and one with the FLAG epitope tag (FLAG-TBX5) (5, 6). Another expression construct was made that expresses a GST-TBX5 fusion protein in the vector pGEX-2T-1. The full-length cDNA of human SC35 was isolated by RT-PCR using total RNA from HeLa cells and cloned into the pcDNA3.1A vector, resulting in a mammalian expression construct for the 6xHis-SC35 protein. Expression constructs for TBX5 with missense mutations were described previously (5, 6). An expression plasmid for a mutant TBX5 with the deletion of the C terminus (TBX5 ΔC with amino acid residues 1–278 retained) was created by restriction digestion of the full-length Tbx5 cDNA in pcDNA3, followed by re-ligation. Full-length Tbx5 cDNA was also cloned into the bacterial overexpression vector pET-28b to express and purify 6xHis-TBX5 in Escherichia coli. Splicing reporter gene pCS3-MT-E1A (19) was a generous gift from Dr. Yang Liu at University of Washington School of Medicine. Splicing reporter gene mini-ANF was constructed by PCR and subcloned into the vector pcDNA3.1.

Antibodies for TBX5 (N-20) and SC35 (Y-16) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The monoclonal anti-His antibody (His6) was obtained from Clontech, and the polyclonal anti-GST antibody was from Amersham Biosciences.

Transfection of various cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). In general 100 ng of DNA was used. When multiple plasmids were used, the amount of DNA for each plasmid remained 100 ng.

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins

GST and GST-TBX5 were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified using standard protocols. 6xHis-TBX5 and 6xHis-TBX5/G80R were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), purified by the Ni-NTA-agarose affinity column, and re-natured by dialysis. Baculovirus 6xHis-SC35 was a generous gift from J. Prasad and J. Stevenin and was purified as described (20). Purity and concentrations of proteins were determined and verified by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining.

Proteomics

The embryogenic carcinoma cell line P19CL6 nuclear extracts were pretreated with Ni-NTA-agarose resin. Approximately 500 μg of extracts were incubated with purified His6-tagged TBX5 for at least 4 h at 4 °C. After extensively washing with the binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 20% glycerol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol), bound proteins were eluted with the sample buffer (6% SDS, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.5, 10% glycerol, 1% bromphenol blue, and 100 mm dithiothreitol) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Visible protein bands were excised from gels and sequenced by mass spectrometry by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Mass Spectrometry Core Facility.

Protein-Protein Interactions

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed using whole cell protein extracts from mouse cardiomyocytes. Mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated using the perfusion method as described (21). Polyclonal goat anti-TBX5 (or anti-SC35) antibodies (about 2 μg) were incubated with cardiac cell extracts (∼100 μg) for 1–2 h at 4 °C and then incubated with protein A/G-agarose beads. After washing at least three times with phosphate-buffered saline, precipitated proteins were eluted with the sample buffer as described above, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed with the anti-SC35 (or anti-TBX5) antibodies. Purified normal goat IgG was cross-linked to protein A/G-Sepharose beads and used as a negative control.

A co-immunoprecipitation assay was also carried out by co-transfecting HeLa cells with expression plasmids for FLAG-tagged TBX5 and 6xHis-SC35 as described previously (6, 22). HeLa cells did not show detectable expression of TBX5 but had a moderate level of SC35 expression (supplemental Fig. 1).

For in vitro protein-protein interaction assays, purified bacterially expressed GST-TBX5 and baculovirally expressed 6xHis-SC35 were incubated in the presence or absence of 0.1 mg/ml RNase A for 1–2 h on ice, and then Sepharose 4B beads were added to the mixture. After extensive washing with phosphate-buffered saline, bound proteins were eluted with sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with an anti-His antibody to detect SC35. Protein signal was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was also probed with an anti-GST antibody to ensure that similar amounts of GST-TBX5 or control GST were used in different treatments.

RNA Binding Assays

The TBX5-RNA binding assay was performed as described previously (23). In brief, 35S-labeled TBX5 protein was prepared by in vitro transcription/translation using the T7 TnT-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega), and incubated with RNA homopolymers in a total of 0.5 ml of binding buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5% Triton X-100) for 15 min at 4 °C. RNA homopolymers (Sigma) were previously bound to Sepharose 4B (poly(A), P2769), agarose (poly(G), P1908; poly(C),P9827), or to polyacrylhydrazido-agarose (poly(U), P8563). The binding mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C, and the pellets were washed five times with cold binding buffer before resuspending in 20 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The sample was boiled at 96 °C for 6 min and loaded onto a 7.0% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and exposed to x-ray film at −80 °C overnight.

RNA binding assays were also performed using the RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), which is a simple and rapid method for detecting the existence of specific RNA-protein interaction. For the EMSA, an α-32P-labeled single strand ANF RNA probe was incubated with 1 μg of purified TBX5 and/or SC35 in a total of 20 μl of binding buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, and 1.25 μg of poly(dI-dC)) for 30 min on ice. The mixture was loaded onto a 6% native polyacrylamide gel to separate the RNA-protein complex from the free probe. The gel was transferred to filter paper, dried, and exposed to x-ray film.

Splicing Assays

The empty expression vector pcDNA3, pcDNA- TBX5, or pcDNA-SC35 (varying from 100 to 500 ng as specified in each experiment) was co-transfected with 1 μg of the splicing reporter genes mini-ANF or pCS3-MT-E1A minigene in HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Splicing products were analyzed by RT-PCR with a 32P-labeled primer. In brief, total RNA was isolated from transfected cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNase (Sigma), and ensured of no DNA contamination by PCR analysis using the primers listed below, and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to single-stranded cDNA using Superscript II RNase H-reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random primers in a volume of 20 μl. RT-PCR was then carried out to assay the efficiency of splicing. The primers for RT-PCR were as follows: ANF forward, 5′-AGCTCCTTCTCCACCACC-3′, and ANF reverse, 5′- AAGCTGTTACAGCCCAGT-3′;E1A forward, T7 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3′, and E1A reverse R67, 5′-GAGCTTGGGACCTCA-3′. The forward PCR primer was labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase and used in radioactive PCR in a volume of 50 μl containing the 1:50 volume of reverse transcription reaction, 2 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 5 mm KCl, 0.15 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTPs, 0.4 mm of each cold primer, and 0.5 units of Taq polymerase (ABI). PCR products were separated using 5% native polyacrylamide gels. The gels were run at 200 V for 40 min, dried, and exposed to x-ray films. Relative intensity of each splicing band was quantified. RT-PCR for human ICAM-1 was used to ensure the cDNA quality and loading accuracy (forward primer, 5′-CGTGCCGCACTGAACTGGAC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CCTCACACTTCACTGTCACCT-3′). Splicing products were also analyzed using regular RT-PCR and 2% agarose gels (data not shown).

RESULTS

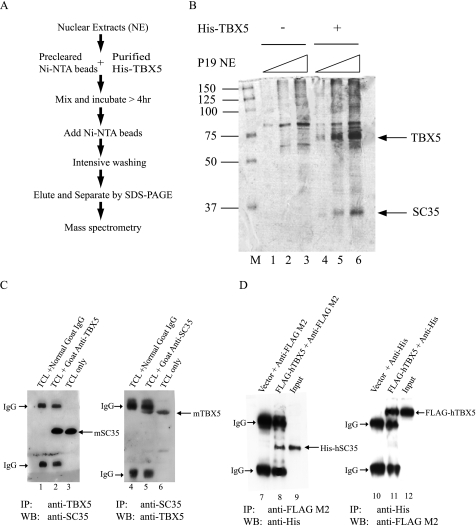

Identification of SC35 as a Candidate Protein Associated with TBX5 by Proteomics

We used a proteomic approach to identify candidate proteins that can form a protein complex with TBX5 as shown in Fig. 1A. His-tagged TBX5 protein (6xHis-TBX5) was purified and used in the Ni2+-NTA affinity bead pulldown experiment (Fig. 1A) to capture novel proteins associated with TBX5. A 35-kDa protein in the P19CL6 nuclear extracts was identified by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B) as a candidate that formed a complex with TBX5. The protein band was excised from the gel, and its identity was defined by mass spectrometry. The protein sequence analysis revealed that the 35-kDa band contains the SC35 protein, a well studied splicing factor that is a member of the SR protein family of splicing factors (13).

FIGURE 1.

TBX5 forms a complex with splicing factor SC35. A, schematic representation of a proteomic approach with the Ni-NTA beads and purified His6-tagged TBX5 to identify TBX5-associating proteins. Nuclear extracts (NE) from P19CL6 cells were precleared with Ni-NTA magnetic agarose beads and incubated with purified His-tagged TBX5 for 4 h. The mixture was then incubated with Ni-NTA beads, washed five times with the lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 150 mm NaCl, mixture of protease inhibitors), and eluted with the elution buffer (8 m urea, 0.1 m NaH2PO4, 0.01 m Tris-HCl, pH 4.5). The eluant was mixed with the SDS protein loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was silver-stained, and the band of interest was excised from the gel and analyzed using mass spectrometry. B, identification of splicing factor SC35 as a protein that associates with TBX5. Purified 6xHis-TBX5 protein was able to pull down a protein of 35 kDa (indicated by an arrow). Mass spectrometry identified the protein as SC35. M, protein molecular weight marker. Lanes 1–3, controls (without TBX5) with increasing amounts of P19CL6 nuclear extracts; lanes 4–6, TBX5 with increasing amounts of P19CL6 nuclear extracts. C, association between TBX5 and SC35 in vivo in cardiac cells detected by co-immunoprecipitation (IP). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.15 ml of heparin (1000 units/ml) and anesthetized with 0.65 ml/kg Nembutal (50 mg/ml). Hearts were excised, and cardiac cells were isolated by a Langendorff perfusion procedure. Left panel, total cardiac cell lysates (TCL) containing both TBX5 and SC35 were incubated with a goat anti-TBX5 antibody (lane 2) or goat IgG (negative control, lane 1), and the immune complex was precipitated with anti-goat IgG-agarose beads and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot (WB) with an anti-SC35 antibody shows that TBX5 forms a complex with SC35. TCL only, input showing expression of SC35 in cardiomyocytes (lane 3). Co-eluted IgGs are indicated by arrows. Right panel, similar analysis as in the left panel except that the anti-SC35 antibody was used in immunoprecipitation, and Western blot analysis was performed with the goat anti-TBX5 antibody. D, association between TBX5 and SC35 in vivo in transfected HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids for FLAG-hTBX5 and/or 6xHis-hSC35. Lanes 7–9, immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG M2 antibody and Western blot with an anti-His antibody to detect SC35. Lanes 10–12, immunoprecipitation with an anti-His antibody and Western blot with an anti-FLAG M2 antibody to detect TBX5.

TBX5 Forms a Complex with SC35

The complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation assays using mouse cardiac cells. Mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated using the Langendorff perfusion method (21), and total protein extracts were prepared. Both TBX5 and SC35 proteins were abundantly expressed in cardiac cells and detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 6). Proteins in isolated mouse cardiomyocyte extracts were precipitated with a polyclonal antibody against TBX5 (Fig. 1C, lane 2). Normal goat IgG was used as a negative control (Fig. 1C, lane 1). The bound proteins were then detected by immunoblot analysis. The TBX5 antibody precipitated a 35-kDa protein that was recognized by an antibody against SC35 (Fig. 1C, lane 2). Similar experiments revealed that the anti-SC35 antibody could precipitate TBX5 from mouse cardiac cell extracts (Fig. 1C, lane 5). These results indicate that TBX5 forms a complex with SC35 in cardiomyocytes.

The association between TBX5 and SC35 was also studied in HeLa cells. TBX5 is not expressed in HeLa and HEK-293 cells, but SC35 is expressed in all cell types, including P19CL6, HeLa, HEK-293, THP1, and COS-7 cells (see supplemental Fig. 1 and some data not shown). Human TBX5 tagged with a FLAG epitope and human SC35 tagged with His6 were co-expressed in HeLa cells, and their association was examined using co-immunoprecipitation. As show in Fig. 1D, the anti-FLAG M2 antibody (for FLAG-TBX5) precipitated His-SC35 that was recognized by the anti-His antibody (lane 8). The anti-His antibody (for SC35) precipitated FLAG-TBX5 that was recognized by the anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 1D, lane 11). These results indicate that TBX5 forms a complex with SC35 in HeLa cells.

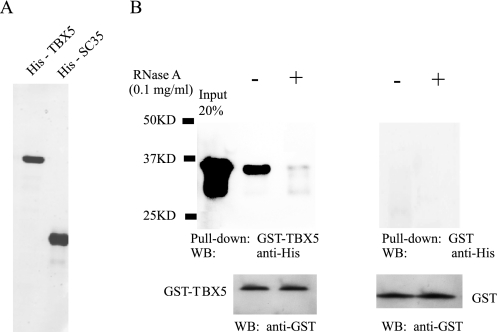

RNA Is Required for the Association between TBX5 and SC35

Interestingly, strong association between TBX5 and SC35 required the presence of RNA. Purified GST-TBX5 fusion protein (Fig. 2A) was incubated with 6xHis-SC35 purified from a baculoviral expression system (Fig. 2A) and immobilized onto glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. Bound proteins were eluted and separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and analyzed by Western blot using a monoclonal anti-His antibody to detect SC35. Consistent with the data from co-immunoprecipitation assays, a strong complex formation was detected between GST-TBX5 and His-SC35 (Fig. 2B). GST-TBX5, but not GST alone, easily pulled down His-SC35. Pretreatment of prepared TBX5 and SC35 with RNase A reduced the association of TBX5 with SC35 (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that RNA is involved in the formation of the TBX5-SC35 complex.

FIGURE 2.

RNA is required for the association between TBX5 and SC35. A, quality of purified GST-TBX5 (left lane) and His-SC35 purified from the insect baculoviral expression system (right lane) was verified by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining. B, purified GST-TBX5 (left panel) or GST (right panel) was incubated with His-SC35. GST pulldown was then performed with Sepharose 4B beads, and the precipitates were analyzed with immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody to detect SC35. Similar GST pulldown experiments were carried out with RNase A-treated mixture (lane +). Immunoblotting with an anti-GST antibody was performed to ensure that an equal amount of GST-TBX5 or GST was used in experiments with and without RNase A treatment. WB, Western blot analysis.

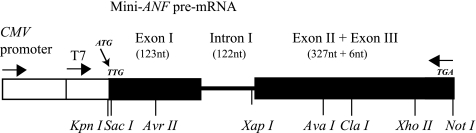

TBX5 Regulates Constitutive Pre-mRNA Splicing

Because TBX5 forms a complex with a splicing factor SC35, we hypothesized that TBX5 could mediate pre-mRNA splicing. To test this hypothesis, we performed mRNA splicing assays in HeLa cells using a mini-ANF splicing gene we constructed (Fig. 3). ANF (atrial natriuretic factor) is a cardiac gene that has been shown to be transcriptionally regulated by TBX5 (6, 25, 26). The mini-ANF gene consists of the CMV promoter, T7 promoter, a portion of exon 1 that starts with the start codon ATG (but mutated to TTG to prevent translation), complete intron I, and complete exon II connected directly to complete exon III (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Schematic diagram of the splicing reporter gene mini-ANF. The mini-ANF gene is composed of the pCMV promoter, portion of exon 1 starting with start codon (mutated to TTG), intron 1, and fusion of exon 2 and exon 3. The mini-ANF gene is also under the control of the T7 promoter in vector pcDNA3. nt, nucleotide.

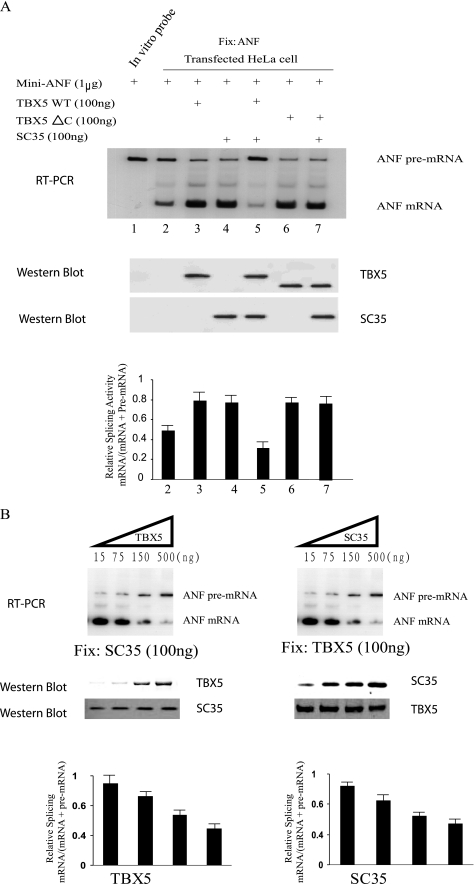

The mini-ANF gene (1 μg) was co-transfected with an expression plasmid for TBX5 (100 ng), SC35 (100 ng), or a combination of TBX5 and SC35 (100 ng each), and the splicing products of mini-ANF were analyzed by RT-PCR with one of the primers labeled by 32P. As shown in Fig. 4A, transient transfection of the mini-ANF gene in HeLa cells resulted in a basal level of splicing (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Co-transfection of the mini-ANF gene and a TBX5 expression construct increased the splicing activity (Fig. 4A, lane 3), suggesting that TBX5 increase the efficiency of splicing of its target gene ANF. Transfection of a mutant TBX5 protein with the deletion of the C terminus (TBX5 ΔC with amino acid residues 1–278 retained) had a similar splicing activity as wild type TBX5 in HeLa cells (Fig. 4, lane 6), suggesting that the TBX5 domain responsible for splicing is located at the N terminus. Co-transfection of SC35 with the mini-ANF gene also resulted in an increase in splicing of ANF (Fig. 4A, lane 4), which is consistent with previously reported results that SC35 facilitates splicing (13, 27).

FIGURE 4.

TBX5 increases the efficiency of pre-mRNA splicing in vivo. A, TBX5 stimulates the splicing activity of the cardiac specific gene ANF. Mini-ANF gene was co-expressed with TBX5, SC35, or both in HeLa cells. Splicing was assayed by radioactive RT-PCR with total cellular RNA and one of the primers labeled by [γ-32P]ATP. The precursor mRNA and spliced products are indicated. The image was scanned, and the intensity of bands was quantified and used to calculate relative splicing activity (mRNA/(mRNA + pre-mRNA) (n = 3). The expression level of the TBX5 or SC35 proteins was verified by Western blot analysis. Note that lane 1 is a positive control with mini-ANF plasmid DNA as template for PCR. B, TBX5 and SC35 antagonize each other in splicing. In vivo splicing assays were carried out with increasing amounts of TBX5 and a fixed amount of SC35 (left panel) or vice versa (right panel). The experiment was replicated once (n = 2).

Surprisingly, co-expression of both TBX5 and SC35 resulted in inhibition of splicing to the basal splicing level (Fig. 4A, lane 5). The inhibitory effect of TBX5 on SC35-mediated splicing was investigated with varying concentrations of TBX5, and the inhibition appeared to be concentration-dependent (Fig. 4B). Similarly, SC35 antagonized the positive effect of TBX5 in splicing, and the effect was also concentration-dependent (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that co-expression of TBX5 and SC35 antagonizes each other in pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa cells. The inhibitory effect on pre-mRNA splicing disappeared with co-expression of SC35 and mutant TBX5 ΔC (Fig. 4A, lane 7). The result suggests that the C terminus of TBX5 is involved in antagonizing the splicing activity of SC35.

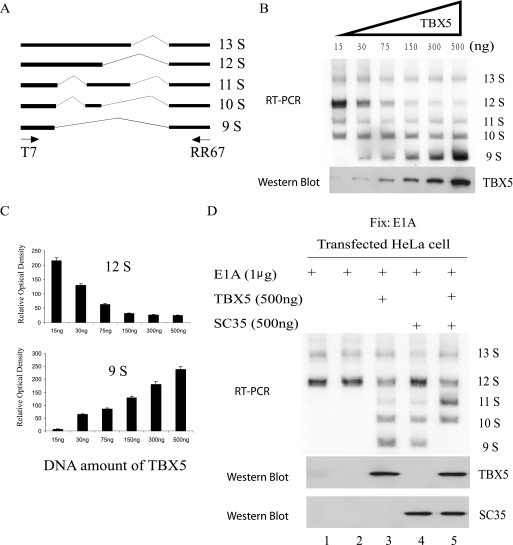

TBX5 Affects Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing

The functional significance of the TBX5-SC35 complex formation was also studied in the alternative splicing process using an E1A minigene (19). The adenovirus E1A pre-mRNA minigene is a well established in vivo splicing system to monitor concentration-dependent changes of the splicing patterns by SR proteins (utilization of different splicing sites results in five isoforms as follows: 13S, 12S, 11S, 10S, and 9S; Fig. 5A) (19, 28). The E1A minigene was co-transfected with varying concentrations of an expression construct for TBX5. The in vivo alternative splicing assay detected five RT-PCR bands at high concentrations of TBX5 (Fig. 5B). The five RT-PCR bands were isolated from the gel and sequenced using the forward T7 primer. The direct DNA sequence analysis indicates that the five bands from 9S to 13S represent the five alternatively spliced isoforms of the mini-E1A pre-mRNA as shown in Fig. 5A (data not shown). As the concentration of TBX5 increased, the amount of the 12S splicing product decreased, although amount of the 9S splicing form increased (Fig. 5, B and C). These results suggest that TBX5 can regulate the selection of alternative splice sites during splicing.

FIGURE 5.

TBX5 regulates the alternative splice site selection during splicing. A well established splicing reporter gene adenovirus E1A minigene was used in an in vivo splicing assay. A, schematic representation of the alternative spliced isoforms of the E1A pre-mRNA. The major isoforms 13S, 12S, 11S, 10S, and 9S are generated by various splice sites. Primers used for analyzing splicing are T7 and RR67 (5′-GAG CTT GGG ACC TCA-3′) and are indicated by arrows. B, minigene E1A was co-expressed with varying amounts of DNA for the TBX5 expression plasmid in HeLa cells, and splicing products were analyzed by 32P RT-PCR. The expression level of TBX5 was monitored by Western blot analysis. C, image in B was scanned, and intensities of 12S and 9S bands were quantified as arbitrary relative optical density, and plotted. Results are expressed as relative intensities of corresponding bands (n = 3). D, effects of co-expression of TBX5 and SC35 on the alternative splice site selection in alternative splicing. The expression levels of TBX5 and SC35 were monitored by Western blot analysis.

Overexpression of SC35 in HeLa cells also led to the formation of the five alternative splicing forms (Fig. 5D, lane 4). Surprisingly, co-expression of TBX5 and SC35 resulted in a dramatic decrease in the amount of the 9S form of mRNA, whereas an increase in the amount of the 11S forms was detected (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 alters the selection of splice sites of the adenovirus E1A pre-mRNA during splicing.

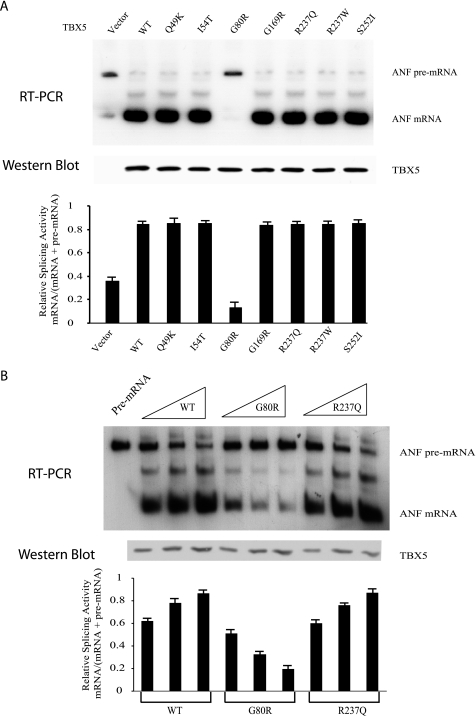

Disease-causing Mutation G80R of TBX5 Significantly Altered the Pre-mRNA Splicing Activity of TBX5

The effect of six pathogenic missense mutations of TBX5 on splicing was examined. The mini-ANF gene was co-transfected with wild type or mutant TBX5 expression constructs in HeLa cells, and in vivo splicing was monitored by RT-PCR of the spliced products. Compared with the vector, wild type TBX5 markedly increased the splicing of the mini-ANF gene (Fig. 6A). Mutations Q49K, I54T, G169R, R237Q, R237W, and S252I acted similarly to wild type TBX5 and promoted splicing to the same level as the wild type protein (Fig. 6A). However, TBX5 with mutation G80R lost its splicing activity (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of TBX5 missense mutations on the splicing activity of TBX5. A, minigene ANF was co-expressed with wild type TBX5 or TBX5 with individual missense mutations in HeLa cells, and splicing was analyzed by 32P RT-PCR (n = 4). ICAM was used as an internal control for RT-PCR (data not shown). Note that mutation G80R reduced the splicing activity of TBX5. The expression levels of wild type and mutant TBX5 proteins were monitored by Western blot analysis. B, missense mutation G80R results in concentration-dependent reduction of TBX5-mediated splicing. Splicing activity was assayed by 32P RT-PCR with 6% polyacrylamide gels (n = 2). The images were scanned, and intensities of bands were quantified and used to calculate relative splicing activity (mRNA/(mRNA + pre-mRNA)).

The splicing activity of TBX5 appears to be concentration-dependent as increased TBX5 resulted in significant increases of the spliced mRNA of the mini-ANF gene (Fig. 6B, WT and R237Q). Increased concentrations of mutant TBX5 with mutation G80R led to gradual decreases of the spliced products (Fig. 6B, G80R), suggesting that suppression of TBX5-mediated splicing activity by mutation G80R was concentration-dependent. The results suggest that TBX5 mutation G80R led to reduced splicing efficiency of TBX5.

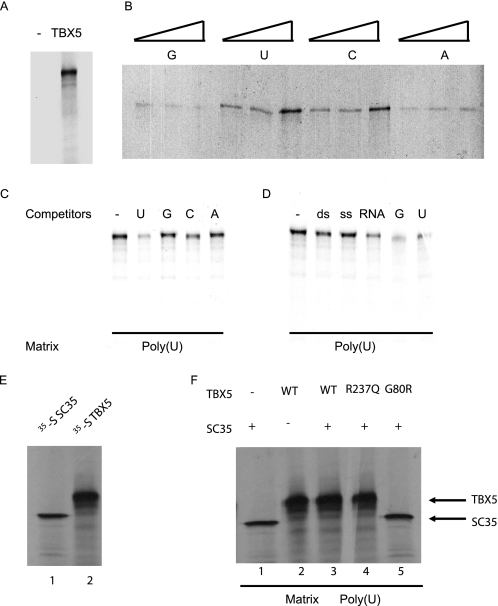

TBX5 Binds to RNA Homopolymers

Because TBX5 plays a role in pre-mRNA slicing, we tested the hypothesis that TBX5 may be an RNA-binding protein using standard binding assays with RNA homopolymers. We demonstrated that 35S-labeled TBX5 was able to bind to various RNA homopolymers (Fig. 7, A and B). The binding of TBX5 to poly(U) and poly(C) RNA was stronger than that to poly(A) and poly(G) RNA (Fig. 7B). Binding of TBX5 to poly(U) RNA was competed more strongly by poly(U) and poly(C) RNA (Fig. 7C). Total RNA from HeLa cells was able to compete for binding of TBX5 to poly(U) RNA more efficiently than double-stranded or single-stranded DNA (Fig. 7D). Together, all these results suggest that TBX5 has RNA binding activity.

FIGURE 7.

TBX5 binds to RNA homopolymers. A, in vitro synthesis of 35S-labeled TBX5 protein. 0.5 μg of expression plasmid for TBX5, pcDNA3-TBX5 (35S-TBX5), or the control empty vector pcDNA3 was incubated with the T7 TnT-coupled transcription/translation systems in the presence of [35S]methionine (1,000 cpm). The mixture was separated by 7% SDS-PAGE and exposed to x-ray film. B, RNA binding of TBX5. 1, 2.5, or 4 μl of 35S-TBX5 was incubated with different matrix-attached RNA homopolymers (25 μg, G, U, C, A), and bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Note that the affinity of TBX5 to poly(U) RNA was the strongest. C, competition with different RNA homopolymers. Binding of 35S-TBX5 to poly(U) RNA attached to polyacrylhydrazido-agarose beads was competed with a 2.5-fold excess of RNA homopolymers (poly(U), poly(G), poly(C), and poly(A)). Note that poly(U) and poly(C) RNA were able to compete for binding of TBX5 to poly(U) RNA. D, competition with 6-fold excess of double-stranded pcDNA3 DNA (ds), heat-denatured single-stranded pcDNA3 DNA (ss), and total RNA isolated from HeLa cells. Note that total HeLa cell RNA was able to compete for binding of TBX5 to poly(U) RNA. E, binding of in vitro synthesized, 35S-labeled SC35 and 35S-labeled TBX5 to poly(U) RNA, respectively. F, poly(U) RNA binding in the presence of both TBX5 and SC35. WT, wild type TBX5; R237Q and G80R, mutant TBX5 protein with mutation R237Q and G80R, respectively.

The same RNA binding assay showed that SC35 can also bind to poly(U) RNA (Fig. 7E). When both TBX5 and SC35 were used in the assay, only TBX5 remained bound to poly(U) RNA. The results suggest that TBX5 and SC35 can compete for binding to poly(U) RNA and that TBX5 overrides SC35 during the binding. Two TBX5 mutations were studied. The TBX5 protein with mutation R237Q had a similar function as wild type TBX5 to override the binding of SC35 to poly(U) RNA (Fig. 7F). However, mutation G80R did not bind to the RNA and did not override the binding of SC35 to poly(U) RNA (Fig. 7F).

TBX5 Binds to mRNA with the 5′-Splice Site

To identify a specific RNA-binding site for TBX5, we focused on the ANF minigene because its splicing activity is increased by TBX5 (Fig. 4). The ANF minigene has only one intron, and thus we studied the 5′-splice site and 3′-splice site on the left and right site of this intron, respectively. RNA probes contain the 5′-splice site (5′SS) and the 3′-splice site (3′SS) (Fig. 8A) and were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, labeled with [32P]ATP, and used in EMSAs in the presence and absence of purified recombinant TBX5 protein. A TBX5-RNA complex was consistently detected with the 5′SS in the presence of TBX5 but not with the 3′SS (Fig. 8B), suggesting that TBX5 can bind to the 5′-splice site. To assess the specificity of the binding of TBX5 to the 5′SS, EMSAs were carried out for a mutant RNA probe with the three exonic nucleotides AAG closest to the intron mutated to GGG. The mutation abolished the binding of TBX5 to the 5′SS (Fig. 8C). In similar assays, SC35 also showed binding to 5′SS, and the mutation also abolished binding of SC35 to the 5′SS (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that both TBX5 and SC35 can bind to the same target RNA site. In the presence of both TBX5 and SC35, only the TBX5-RNA complex was detected (Fig. 8D), suggesting that TBX5 and SC35 can compete for binding to the 5′SS, and that TBX5 overrides SC35 during the binding. Mutant TBX5 with mutation R237Q remained bound to the RNA when SC35 was present, whereas mutant TBX5 with G80R did not bind to the RNA and failed to override the binding of SC35 to the 5′SS (Fig. 8D).

FIGURE 8.

Binding of TBX5 to the 5′-splice site, but not to the 3′-splice site of the ANF minigene. A, sequences of RNA probe used in the RNA EMSA. Capital letters represent exonic sequences and lowercase letters are intronic sequences. Mutated sequences at the 5′-splice site, from AAG to GGG, are underlined. WT, wild type; Mut, mutant. B, TBX5 binds to the 5′-splice site and not to the 3′-splice site. Lane 1, 3′SS probe only; lane 2, 3′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein; lane 3, 5′SS probe only; lane 4, 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein. C, both TBX5 and SC35 bind to the 5′ exonic splicing site. Lane 1, WT 5′SS probe only; lane 2, WT 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein; lane 3, WT 5′SS probe with purified SC35 protein; lane 4, mutant 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein; lane 5, mutant 5′SS probe with purified SC35 protein. D, TBX5 competes with SC35 for binding to 5′SS RNA. Lane 1, WT 5′SS probe only; lane 2, WT 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein; lane 3, WT 5′SS probe with purified SC35 protein; lane 4, 30× excess of cold WT probe was add to the RNA binding mixture as in lane 2; lane 5, WT 5′SS probe with both TBX5 and SC35; lane 6, WT 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein with mutation R237Q; lane 7, WT 5′SS probe with purified TBX5 protein with mutation G80R.

DISCUSSION

TBX5 has been established as a transcriptional factor (5, 25, 26). The interactions between TBX5 and NK2.5, GATA-4, or SALL4 have been shown to be important in the regulation of cardiac transcriptional processes during heart development (5, 25, 26, 29, 30). This study has identified a novel function for TBX5 in pre-mRNA splicing. We have found that TBX5 forms a complex with an SR splicing factor SC35. The marked effect of TBX5 on stimulating the efficiency of constitutive pre-mRNA splicing was demonstrated in splicing assays with a mini-ANF splicing reporter gene. TBX5 was also shown to regulate alternative splicing (selection of splice sites) during splicing as revealed by splicing assays that involved a mini-E1A splicing reporter gene. These results suggest that TBX5 is involved in pre-mRNA splicing. To the best of our knowledge, TBX5 is the first human disease protein that exhibits a dual functional role in transcriptional activation and pre-mRNA splicing. TBX5 is also the first cardiac transcription factor that functions as a pre-mRNA splicing factor.

Multiple assays clearly showed that TBX5 formed a complex with SC35 (Figs. 1 and 2). Co-immunoprecipitation with protein extracts from HeLa cells transfected with both TBX5 and SC35 showed the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35. Similar results were obtained with protein extracts that were isolated from mouse cardiomyocytes. In vitro GST-pulldown assays also showed the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35. RNA appears to be involved in the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 (Fig. 2).

A surprising finding from this study was that during splicing TBX5 acted in a similar fashion as to SR proteins, such as SC35, and was involved in both constitutive splicing and alternative splicing. In constitutive splicing, the SR proteins have redundant functions such that SC35 and other SR proteins may be able to cooperate or compete with the remainder of the splicing machinery to stimulate or inhibit splicing. Although SR proteins contain an RNA-binding domain, sequence-specific interactions with the pre-mRNA were assumed to play a minimal role for the function in constitutive splicing (31). Instead, the RS domain of SR proteins may mediate protein-protein interactions that stabilize snRNP interactions (31) and result in increased splicing. In contrast, RNA binding by TBX5 may be involved in constitutive splicing. First, RNA binding assays showed consistently that TBX5 was able to bind to RNA (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). Second, TBX5 binding to RNA has specificity. It has stronger affinity to poly(U) and poly(C) RNAs. More importantly, TBX5 binds specifically to the 5′-splice site of the ANF minigene but not to the 3′-splice site. Furthermore, a mutant TBX5 protein carrying the G80R mutation is no longer functional in stimulating splicing (Fig. 6, A and B) and does not bind to RNAs; TBX5 with mutation R237Q is functional in increasing splicing and can bind to RNAs (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

This study shows that the N terminus of TBX5 may be involved in constitutive splicing. A mutant TBX5 protein missing the C terminus worked as efficiently as wild type TBX5 in increasing the rate of splicing (Fig. 4A). The finding that mutation G80R located at the N terminus of TBX5 inhibited pre-mRNA splicing of the ANF minigene also argues that the N terminus of TBX5 plays an important role in splicing. The role of the TBX5 domain containing the Gly-80 residue is not fully understood, but results from RNA binding assays suggest that it may be involved in binding of TBX5 to RNA (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

In alternative splicing, SR proteins may activate splice site selection by a different mechanism that involves sequences in mRNA called exonic splicing enhancers (10, 32). SR proteins can bind to exonic splicing enhancers, and the resulting complexes may interact with general splicing factors to facilitate utilization of adjacent splice sites. Increased TBX5 expression shifted the major spliced product of the mini-E1A gene from the 12S form to the 9S form (Fig. 5A). Co-expression of TBX5 together with SC35 shifted the major spliced product of the mini-E1A gene from the 9S form to the 11S form (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that TBX5 is involved in alternative splicing and that the interaction between TBX5 and SC35 has a major impact on the selection of splicing sites during splicing.

Mutations in splicing factors can cause human diseases. Retinitis pigmentosa, one of the severe retinal diseases, has been linked to mutations in three genes that encode essential splicing factors as follows: PRPC8 on chromosome 17p13.3 (RP13) coding for PRP8 (a core component of the U5 snRNP), HPRP3 on 1p13-q21 (RP18) for PRP3 (a component of the U4/U6), and PRPF31 on 19q13.4 (RP11) that encodes human pre-mRNA splicing factor PRP31 required for U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP formation (33). Our finding that TBX5 plays a critical role in constitutive splicing and alternative splicing demonstrates an association in defects in pre-mRNA splicing to a cardiac disorder in humans. The results from this study extend the role of splicing factors in human diseases from an eye disorder to a cardiac disorder.

Many mutations in TBX5 have been identified in patients affected with Holt-Oram syndrome, and genotype-phenotype analyses have revealed high inter- and intra-familial variability of expressivity (4, 5). It is interesting to note that all reported Holt-Oram syndrome cases were presented with some degrees of limb malformations, but the penetrance of the cardiac phenotype was not complete and was estimated to be less than 75%. Basson et al. (4) performed detailed phenotypic analysis for families with TBX5 mutations G80R and R237Q/R237W. Interestingly, G80R showed full penetrance of the cardiac phenotype (19:19), whereas R237Q/R237W mutations showed only 54% penetrance (14:26) (4). This difference cannot be explained by transcriptional regulation alone as our previous study reported that both G80R and R237R/R237W mutations reduced DNA binding and transcription activation activities of TBX5 (6). The difference in penetrance of the cardiac phenotype between G80R and R237R/R237W may be related to our finding that G80R, but not R237Q and R237W, significantly reduces the pre-mRNA splicing activity of TBX5 (Fig. 6).

This study has several limitations. First, the exact role of the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 in splicing is not clear. We speculate that TBX5 binds to the 5′-splice site of pre-mRNA, which facilitates the interaction of TBX5 with the spliceosome, resulting in increased splicing. The binding of TBX5 to RNAs is important for splicing because mutation G80R impairs the RNA binding of TBX5 (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8) and inhibits splicing (Fig. 6). SC35 can also bind to other splicing factors of the splicing machinery to stimulate splicing. In the presence of both TBX5 and SC35, the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 may alter the conformation of the spliceosome, resulting in inhibition of splicing. Alternatively, the complex formation between TBX5 and SC35 may compete for the interaction of SC35 and/or TBX5 to other SR proteins and splicing factors, resulting in inhibition of splicing. Examples of proteins that inhibit splicing by antagonizing the role of other splicing factors have been described. In bovine growth hormone intron D splicing, stimulatory effects of SR protein ASF/SF2 was blocked by hnRNP A1 (34). SC35 abolishes the stimulatory effect of ASF/SF2 on splicing of exon 6A of the chicken β-tropomyosin gene in non-muscle and smooth muscle cells (27). Future studies are needed to further dissect the molecular mechanisms by which TBX5 mediates pre-mRNA splicing. Second, at the present time, we cannot exclude that possibility that the effect of TBX5 on splicing of the ANF minigene may be through the transcriptional induction of splicing factor genes by TBX5. However, the results on two TBX5 mutations, G80R and R237Q, are not consistent with this possibility. Both TBX5 mutations reduce transcription activity of TBX5 (6), but the G80R mutation inhibits TBX5-mediated splicing of the ANF minigene, whereas R237Q stimulates splicing as wild type TBX5. Therefore, the transcriptional induction of splicing factor genes by TBX5 may not be directly related to its splicing activity.

In summary, we have shown that transcriptional factor TBX5 plays a critical, dual role in both transcriptional activation and pre-mRNA splicing (both constitutive splicing and alternative splicing). We have also demonstrated that defects in splicing caused by a TBX5 mutation G80R is directly linked to the pathogenesis of Holt-Oram syndrome, and this defines a novel mechanism for the pathogenesis of a congenital heart disease. The results also provide a fundamental understanding of the roles of a critical protein factor, TBX5, in the development of the heart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jayendra Prasad, Hua Lou, Richard A. Padgett, Wei Du, Shenghan Chen, and Tie Ke for discussion, scientific input, and technical help; Sandro Yong for isolated cardiomyocytes; Yang Liu for the generous gift of pCS3-MT-E1A; J. Prasad and J. Stevinin for baculovirus 6xHis-SC35; Donal Luse, Ganes C. Sen, and Sara Seidelmann for their critical reading of the manuscript; and members of the Wang laboratory for their discussion. We also thank Mike Kinter and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Mass Spectrometry Core Facility for their excellent service.

This work was supported in part by China Natural Science Foundation Grant 30670857 (to Q. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- snRNP

- small nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- RT

- reverse transcription

- SS

- splice site

- WT

- wild type

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Papaioannou V. E., Silver L. M. (1998) BioEssays 20, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basson C. T., Bachinsky D. R., Lin R. C., Levi T., Elkins J. A., Soults J., Grayzel D., Kroumpouzou E., Traill T. A., Leblanc-Straceski J., Renault B., Kucherlapati R., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. (1997) Nat. Genet. 15, 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q. Y., Newbury-Ecob R. A., Terrett J. A., Wilson D. I., Curtis A. R., Yi C. H., Gebuhr T., Bullen P. J., Robson S. C., Strachan T., Bonnet D., Lyonnet S., Young I. D., Raeburn J. A., Buckler A. J., Law D. J., Brook J. D. (1997) Nat. Genet. 15, 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basson C. T., Huang T., Lin R. C., Bachinsky D. R., Weremowicz S., Vaglio A., Bruzzone R., Quadrelli R., Lerone M., Romeo G., Silengo M., Pereira A., Krieger J., Mesquita S. F., Kamisago M., Morton C. C., Pierpont M. E., Müller C. W., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2919–2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan C., Duhagon M. A., Oberti C., Chen S., Hiroi Y., Komuro I., Duhagon P. I., Canessa R., Wang Q. (2003) J. Med. Genet. 40, e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C., Liu M., Wang Q. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8780–8785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh T. K., Packham E. A., Bonser A. J., Robinson T. E., Cross S. J., Brook J. D. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1983–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black D. L. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 291–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graveley B. R. (2000) RNA 6, 1197–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tacke R., Manley J. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 358–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding J. H., Xu X., Yang D., Chu P. H., Dalton N. D., Ye Z., Yeakley J. M., Cheng H., Xiao R. P., Ross J., Chen J., Fu X. D. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahler A. M., Damgaard C. K., Kjems J., Caputi M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10077–10084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu X. D., Maniatis T. (1992) Science 256, 535–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maniatis T., Reed R. (2002) Nature 416, 499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proudfoot N. J., Furger A., Dye M. J. (2002) Cell 108, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge H., Si Y., Wolffe A. P. (1998) Mol. Cell 2, 751–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monsalve M., Wu Z., Adelmant G., Puigserver P., Fan M., Spiegelman B. M. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C., Dowd D. R., Staal A., Gu C., Lian J. B., van Wijnen A. J., Stein G. S., MacDonald P. N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35325–35336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L., Embree L. J., Tsai S., Hickstein D. D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27761–27764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasad J., Colwill K., Pawson T., Manley J. L. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 6991–7000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian X. L., Yong S. L., Wan X., Wu L., Chung M. K., Tchou P. J., Rosenbaum D. S., Van Wagoner D. R., Kirsch G. E., Wang Q. (2004) Cardiovasc. Res. 61, 256–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian X. L., Kadaba R., You S. A., Liu M., Timur A. A., Yang L., Chen Q., Szafranski P., Rao S., Wu L., Housman D. E., DiCorleto P. E., Driscoll D. J., Borrow J., Wang Q. (2004) Nature 427, 640–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue A., Takahashi K. P., Kimura M., Watanabe T., Morisawa S. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 2990–2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deleted in proof

- 25.Bruneau B. G., Nemer G., Schmitt J. P., Charron F., Robitaille L., Caron S., Conner D. A., Gessler M., Nemer M., Seidman C. E., Seidman J. G. (2001) Cell 106, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiroi Y., Kudoh S., Monzen K., Ikeda Y., Yazaki Y., Nagai R., Komuro I. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallego M. E., Gattoni R., Stévenin J., Marie J., Expert-Bezançon A. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1772–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cáceres J. F., Misteli T., Screaton G. R., Spector D. L., Krainer A. R. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 138, 225–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg V., Kathiriya I. S., Barnes R., Schluterman M. K., King I. N., Butler C. A., Rothrock C. R., Eapen R. S., Hirayama-Yamada K., Joo K., Matsuoka R., Cohen J. C., Srivastava D. (2003) Nature 424, 443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshiba-Takeuchi K., Takeuchi J. K., Arruda E. P., Kathiriya I. S., Mo R., Hui C. C., Srivastava D., Bruneau B. G. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J. Y., Maniatis T. (1993) Cell 75, 1061–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blencowe B. J. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q., Chen Q. (2003) Nature Encyclopedia of Human Genome 5, 38–44 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Q., Mayeda A., Hampson R. K., Krainer A. R., Rottman F. M. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 2598–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.