Abstract

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is an immune-mediated chronic cholestatic liver disease with a slowly progressive course. Without treatment, most patients eventually develop fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver and may need liver transplantation in the late stage of disease. PBC primarily affects women (female preponderance 9–10:1) with a prevalence of up to 1 in 1,000 women over 40 years of age. Common symptoms of the disease are fatigue and pruritus, but most patients are asymptomatic at first presentation. The diagnosis is based on sustained elevation of serum markers of cholestasis, i.e., alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase, and the presence of serum antimitochondrial antibodies directed against the E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Histologically, PBC is characterized by florid bile duct lesions with damage to biliary epithelial cells, an often dense portal inflammatory infiltrate and progressive loss of small intrahepatic bile ducts. Although the insight into pathogenetic aspects of PBC has grown enormously during the recent decade and numerous genetic, environmental, and infectious factors have been disclosed which may contribute to the development of PBC, the precise pathogenesis remains enigmatic. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is currently the only FDA-approved medical treatment for PBC. When administered at adequate doses of 13–15 mg/kg/day, up to two out of three patients with PBC may have a normal life expectancy without additional therapeutic measures. The mode of action of UDCA is still under discussion, but stimulation of impaired hepatocellular and cholangiocellular secretion, detoxification of bile, and antiapoptotic effects may represent key mechanisms. One out of three patients does not adequately respond to UDCA therapy and may need additional medical therapy and/or liver transplantation. This review summarizes current knowledge on the clinical, diagnostic, pathogenetic, and therapeutic aspects of PBC.

Keyword: Cholestasis, PBC, Liver, Pathogenesis, UDCA, Autoimmune liver disease

Introduction

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) [1] is an immune-mediated chronic progressive inflammatory liver disease that leads to the destruction of small interlobular bile ducts, progressive cholestasis, and, eventually, fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver without medical treatment commonly necessitating liver transplantation. Addison and Gull [2] have first described a disease with a PBC-like picture in 1851, but the term “primary biliary cirrhosis” was coined in 1949 when a cohort of 18 patients with characteristic features of PBC was published [3]. PBC, predominantly affecting middle-aged women, is characterized by biochemical markers of cholestasis, serum antimitochondrial autoantibodies (AMA), and lymphocytic infiltration of the portal tracts of the liver [4]. Histologically, the hallmark of the disease is damage to biliary epithelial cells (BEC) and loss of small intrahepatic bile ducts accompanied by significant portal tract infiltration with CD4 and CD8 T cells, B cells, macrophages, eosinophils, and natural killer cells [5, 6].

Being one of the first conditions in which specific autoantibodies were recognized, PBC is regarded as a “model autoimmune disease.” Both environmental factors and inherited genetic predisposition appear to contribute to its pathogenesis [7]. Although there has been tremendous progress in unraveling potential pathophysiologic factors in PBC over the past years [7], the actual impact of each of the identified genetic and environmental associations is still controversial. It is the aim of this article to review the current knowledge of major pathologic features in PBC and to try to combine these findings to an overall picture of the pathogenesis of PBC.

The most frequent symptoms in PBC are fatigue and pruritus, occurring in up to 85% and 70% of patients, respectively [8, 9]. Median survival in untreated individuals has been reported to be 7.5 to 16 years [1, 10], but has largely improved since the introduction of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) therapy and liver transplantation. Patients that are treated with UDCA at an early stage of the disease and respond well to therapy may reach normal life expectancy [11–14]. However, the beneficial mechanisms of UDCA treatment are still incompletely understood, and about one third of patients fail to adequately respond to UDCA monotherapy. In the second part of this review, we will therefore summarize the rationale behind UDCA therapy and give an overview on future therapeutic options currently under study.

Epidemiology

PBC occurs in individuals of all ethnic origins and accounts for up to 2.0% of deaths from cirrhosis [15]. It primarily affects women with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life, and it is uncommon in persons under 25 years of age. Incidence and prevalence vary strikingly in different geographic regions (as does the quality of epidemiological studies related to PBC), ranging from 0.7 to 49 and 6.7 to 402 per million, respectively [16–23]. The highest incidence and prevalence rates are reported from the UK [16, 21], Scandinavia [17], Canada [18], and the USA [19, 22], all in the northern hemisphere, whereas the lowest was found in Australia [20]. There is no clear evidence to support or exclude the concept of “a polar–equatorial gradient,” as it has been reported for other autoimmune conditions [24].

Diagnosis

Increased awareness of the condition and the increasing availability of diagnostic tools, in particular serological testing, have led to a more frequent and earlier diagnosis of PBC [25]. More than half of patients diagnosed today with PBC are asymptomatic at presentation [26, 27]. They generally attract attention by findings of elevated serum alkaline phosphatase (AP) and/or total serum cholesterol, especially in asymptomatic patients often during routine checkup. A diagnosis of PBC is made “with confidence” when biochemical markers of cholestasis, particularly alkaline phosphatase, are elevated persistently for more than 6 months in the presence of serum AMA and in the absence of an alternative explanation [28, 29]. In PBC patients, AMA is generally present in high titer. Low-titer AMA may not be specific and may disappear on retesting [30].

Compatible histological findings confirm the diagnosis and allow staging before therapeutic intervention, but in many cases, histological workup is not necessary to diagnose PBC [29].

Biochemical tests

Serum AP and γGT are commonly elevated and define, together with AMA, the diagnosis of PBC. Mildly elevated serum aminotransferases (ALT, AST) are usually observed in PBC but are not diagnostic. Increased serum levels of (conjugated) bilirubin as well as alterations in prothrombin time and serum albumin are late phenomena in PBC like in other cirrhotic states and unusual at diagnosis. However, serum bilirubin is a strong and independent predictor of survival [31] with a high impact on all established models for prognosis.

Serum cholesterol is commonly elevated in patients with PBC, alike other cholestatic conditions. The increased cholesterol level in PBC is largely caused by the presence of LpX [32]. LpX is an abnormal lipid particle which is characteristic for cholestatic liver disease and that is directly derived from biliary lipids that regurgitate into the blood [33]. Upon lipoprotein fractionation, LpX is usually found in the very low-density lipoprotein fraction but is very different from other lipoproteins. In contrast to normal lipoproteins, which have a core filled with neutral lipid, LpX consists of liposomes (with an aqueous lumen) of phospholipids and free cholesterol. LpX is not taken up in atherosclerotic plaques and may reduce the atherogenicity of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by preventing LDL oxidation [34]. Accordingly, the increased serum cholesterol in PBC patients is not associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease. In contrast, long-lasting PBC is associated with the occurrence of xanthomata and xanthelasma. Hypercholesterolemia in PBC patients is responsive to statin treatment. Long-term treatment with UDCA also reduces serum cholesterol [35].

Though not diagnostic, thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should be assessed in any patient who is believed to have PBC due to the high association of PBC with thyroid dysfunction, mainly caused by Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Serology

AMA autoantibodies are pathognomonic for PBC and lead to the diagnosis with a high specificity and sensitivity. AMA-positive individuals, even if no signs of cholestasis and/or liver inflammation are present, are very likely to develop PBC. Mitchison et al. [36], in a small study, evaluated liver pathology of 29 asymptomatic AMA-positive (levels > 1:40) individuals lacking AP elevation. At inclusion, all but two had abnormal liver histology, and in 12, findings were diagnostic for PBC. A 10-year follow-up of these subjects revealed that 24 of the 29 remained AMA-positive; all 24 developed biochemical evidence of cholestasis and 22 became symptomatic [37], confirming a high positive predictive value of positive AMA testing for the development of PBC.

Sensitivity of AMA, however, although high, is limited. Investigators have reported patients who clinically, biochemically, and histologically have all the features of PBC despite consistently negative AMA testing both by immunofluorescence and with the most specific immunoblotting and immunoenzymatic techniques [38–42]. Overall, AMA seems to be negative in 5% of patients who otherwise have all the features typical for PBC [43] and an identical autoreactive CD4 T cell response to the critical autoantigen, PDC-E2 [44]. This small group of AMA-negative patients, however, may erroneously include patients with PBC-like symptoms induced by causes other than autoimmunity, such as patients with mutations in the ABCB4 (MDR3) gene [45]. These patients secrete reduced amounts of phospholipids into the bile, which is harmful to hepatocytes and cholangiocytes.

The pattern of serum immunoglobulin fractions in PBC is characterized by an elevation of serum IgM [46], possibly due to an abnormal chronic B cell activation by Toll-like receptor-dependent signaling [47]. However, specificity of this finding is limited and IgM levels are not commonly used as a diagnostic criterium.

Nonspecific antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or smooth muscle antibodies are found in serum of one third of patients with otherwise clear-cut PBC [48], but are of limited diagnostic value. In contrast, specific ANA directed against nuclear body or envelope proteins such as anti-Sp100, presenting as multiple (6–12) nuclear dots at indirect immunofluorescence staining and anti-gp210, presenting as perinuclear rims have shown a specificity of >95% for PBC, although their sensitivity is low. These specific ANA can be used as diagnostic markers for PBC in the absence of AMA titers [29].

Imaging

Ultrasound examination of the liver and biliary tree is obligatory in all cholestatic patients in order to differentiate intrahepatic from extrahepatic cholestasis. When the biliary system appears normal and serum AMA are present, no further radiologic workup is necessary. Abdominal lymphadenopathy, particularly in the hilar region of the liver, is seen in 80% of patients with PBC [49].

Transient elastography (TE) has been introduced as a new, simple and noninvasive imaging technique for determining the degree of fibrosis in patients with chronic liver diseases, mainly chronic hepatitis C [50]. Corpechot et al. [51] compared liver stiffness as determined by TE (FibroscanR) to histological findings obtained by liver biopsy in 101 patients with PBC (n = 73) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC; n = 28) and showed a highly significant correlation of liver stiffness with both degree of fibrosis and histological stage. Further studies in independent cohorts of PBC patients are warranted before TE can be regarded as an established alternative to liver biopsy in the staging of chronic cholestatic liver disease. Still, TE appears attractive as a screening tool in future therapeutic trials, as it may help overcome the limited staging accuracy of liver biopsy due to heterogeneous distribution of inflammation and fibrosis in PBC.

Liver biopsy/histology

A liver biopsy is not anymore regarded as mandatory for the diagnosis of PBC in patients with elevated serum markers of cholestasis and positive serum AMA [28, 29], but may be helpful in excluding other potential causes of cholestatic disease and in assessing disease activity and stage. A liver biopsy may also be helpful in the presence of disproportionally elevated serum transaminases and/or serum IgG levels to identify additional or alternative processes. Histological staging of PBC (stage 1 to stage 4) is determined by the degree of (peri)portal inflammation, bile duct damage and proliferation, and the presence of fibrosis/cirrhosis according to Ludwig et al. [52] and Scheuer [53]. Stage 1 disease is characterized by portal inflammation with granulomatous destruction of the bile ducts, although granulomas are often not seen. Stage 2 is characterized by periportal hepatitis and bile duct proliferation. Presence of fibrous septa or bridging necrosis is defined as stage 3 and cirrhosis as stage 4 [52]. Findings of fibrotic or cirrhotic changes (stage 3 or 4) are accompanied by a worse prognosis [54]. Florid duct lesions as defined by focal duct obliteration and granuloma formation are regarded as typical for PBC. The liver is not uniformly involved, and features of all four stages of PBC can be found in one biopsy specimen. The most advanced histological features are used for histological staging.

Clinical findings

At diagnosis, the majority of patients are asymptomatic and present e.g. for workup of elevated serum levels of AP or cholesterol [55, 56]. In symptomatic patients, fatigue and pruritus are the most common complaints and have been reported in 21% and 19% of patients at presentation, respectively [27, 57]. Unexplained discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen has been reported in approximately 10% of patients [58]. In the majority of asymptomatic and untreated patients, overt symptoms develop within 2 to 4 years, although one third may remain symptom-free for many years [27, 56].

Fatigue

During the course of the disease, up to 80% of PBC patients complain of chronic fatigue impairing quality of life and interfering with daily life activities [8, 59]. No correlation with the severity of the liver disease could be demonstrated [59], but there is an association with autonomic dysfunction (in particular orthostatic hypotension) [60], sleep disturbance and excessive daytime somnolence [60], and, although weak, depression [61], which might necessitate treatment for themselves. The exact pathophysiological mechanisms leading to chronic fatigue in PBC and other cholestatic diseases are not unraveled so far. Standard therapy of PBC with UDCA and even liver transplantation may fail to improve this often disabling symptom.

Pruritus

PBC is more frequently associated with pruritus than other chronic cholestatic liver diseases. During the course of the disease, pruritus occurs in 20% to 70% of patients and can often be the most distressing symptom [62]. It develops independently of the degree of cholestasis and the stage of disease. Its pathogenesis remains poorly understood and the potential pruritogens in cholestasis are undefined. The therapeutic efficacy of anion exchange resins like cholestyramine, the pregnane X receptor agonist, rifampicin, plasmapheresis, and albumin dialysis as well as nasobiliary drainage led to the conclusion that in cholestasis putative pruritogens accumulate in the circulation, are secreted into bile, and undergo an enterohepatic cycle. Itch could then be induced locally in the skin or in neuronal structures. Bile salt metabolites, progesterone metabolites, histamine, and endogenous opioids, among others, have all been proposed as causative agents. However, evidence for a key role of any of these suggested pruritogens in cholestasis is weak [63].

Portal hypertension

Variceal hemorrhage or other signs of portal hypertension secondary to fibrosis or cirrhosis are uncommon at first presentation, but have occasionally been described [64]. However, portal hypertension as determined by measurement of the portohepatic pressure gradient (PHG) is common in PBC, and a stable or - under treatment -improved PHG is a predictor of survival [65, 66].

Metabolic bone disease

Patients with PBC have been reported to be at increased risk of osteoporosis in some studies [67], but reports in the literature remain contradictory. Patients with advanced PBC may be at particular risk for osteoporosis and may present with osteoporosis and yet be otherwise asymptomatic from their liver disease. The development of osteoporosis in PBC patients has been attributed to both, decreased osteoblast activity and increased osteoclast activity [68]. Metabolism of vitamin D is normal in PBC, but malabsorption of both calcium and vitamin D may occur predominantly in late-stage disease. Pancreatic insufficiency and celiac disease, which are associated with PBC [69–71], may further aggravate malabsorption.

Fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption

When secretion of bile and bile salts is insufficient, i.e., bile salts drop below the critical micellar level in the duodenum, malabsorption of both fat and fat-soluble vitamins may ensue. Serum levels of vitamin A and E have been shown to be low in a minority of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis prior to development of jaundice [72]. Osteomalacia is barely seen in PBC, as a liver transplant is performed in most patients before the development of this complication of prolonged deep jaundice.

Urinary tract infections

Though often asymptomatic, recurrent urinary tract infections have been reported in up to 19% of women with PBC [73], and a potential pathophysiologic relevance of Escherichia coli strains has been suggested.

Malignancy

Reports on the rate of breast carcinoma in women with PBC differ and reported either an increase in risk [74, 75] or equal risk [18, 76] compared to a healthy population.

Hepatocellular carcinoma in late-stage PBC has been reported to occur at rates similar to other kinds of cirrhosis [77–79], but seems to be more frequent in men with PBC: One study reported an average HCC prevalence of 5.9% in advanced PBC (4.1% in women but 20% in men) [77].

Associated disorders

A number of mostly immune-mediated diseases are commonly observed in patients with PBC. Thyroid dysfunction is frequently associated with PBC, often predating its diagnosis [80]. Sicca syndrome is seen in up to 70% of patients [81]. Incomplete or complete CREST syndrome (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud syndrome, esophageal motility disorder, sclerodactyly, teleangiectasia) is not uncommon [82]. Celiac disease has been reported in up to 6% of patients [72] and is by far more commonly associated with PBC than inflammatory bowel diseases [83].

Pathogenesis

A florid bile duct lesion with damage to BEC and subsequent destruction of small bile ducts is the histopathologic hallmark of PBC. The exact pathogenetic mechanisms responsible for BEC damage in PBC remain unknown. Increasing experimental evidence, however, suggests that the florid bile duct lesion in PBC is initiated by environmental trigger(s) acting on a genetically susceptible individual [84].

Pathogenetic factors

Genetic factors/susceptibility

Genetic factors have an impact on PBC pathogenesis that is stronger than that in nearly any other autoimmune disease [85–87]. Accordingly, a concordance rate of about 60% was seen in monozygotic twins (as opposed to nearly 0% for dizygotic twins) [88, 89]. A significantly increased incidence of PBC is seen in relatives of PBC patients [89, 90]. The relative risk of a first-degree relative of a PBC patient is 50- to 100-fold higher than for the general population [91], yielding a prevalence rate up to 5–6% [19, 90, 92]. Interestingly, among affected monozygotic twins, though the age of disease onset is similar, progression and disease severity vary, emphasizing the role of epigenetic and probably environmental factors [89].

It has been difficult to identify distinct susceptibility genes in PBC so far. Genetic associations in PBC were shown with major histocompatibility complex encoded genes. PBC is apparently associated with the DRB1*08 family of alleles, although marked variation is observed between different ethnic groups. Association with the DRB1*0801-containing haplotype is seen in populations of European origin, whereas in populations of Asian origin, an association is seen with the DRB1*0803 allele. A protective association has been described with DRB1*11 and DRB1*13, but once again, significant population differences are observed [93–102]. Both associations of PBC with the DRB1*08 allele as well as the protective association of DRB1*11 and DRB1*13 were recently confirmed in the largest series ever reported including 664 unrelated patients from Italy [103]. The odds ratio for developing PBC was 3.3 for DRB1*08-positive subjects, whereas it was reduced to 0.3 for subjects positive for DRB1*11, to 0.7 for DRB1*13, and to 0.1 for carriers of both DRB1*11 and DRB1*13. This study again highlighted the relevance of geographic variation, with marked differences in allele association between northern and southern Italy.

Associations have also been reported with polymorphisms of genes involved in innate or adaptive immunity. Allelic variations of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), a key regulator of the adaptive immune system, have been repeatedly associated with susceptibility to different autoimmune diseases (such as type I diabetes mellitus and systemic lupus erythematosus) and were also associated with PBC [104–109]. Although an association of CTLA-4 variants and susceptibility to PBC could not be demonstrated in all studies [110, 111], Poupon et al. [112] most recently confirmed a potential role of TNFα and CTLA-4 variants in the pathogenesis of PBC. In 258 PBC patients and two independent control groups of 286 and 269 healthy volunteers, the authors investigated distribution of newly identified htSNPs of 15 selected candidate genes: two related to immunity encoding for CTLA-4 and TNFα, ten genes related to bile formation encoding hepatobiliary transporters, and three related to adaptive response to cholestasis encoding nuclear receptors. In a case–control analysis, only haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNPs) in CTLA-4 and TNFα showed differences in distribution between PBC and controls, confirming their potential role in the pathogenesis of PBC. In contrast, htSNPs of the ten transporter genes as well as the three nuclear receptor genes under study were equally distributed, confirming previous studies of htSNPs in key transporters without major impact [1, 113, 114]. A strong association of the allelic variant TNFα rs 1799724 (C/T) with disease progression was shown. Most interestingly, a strong association with disease progression was also shown for AE2 rs 2303932 (T/A), a gene encoding for the apical anion exchanger 2 (AE2) in cholangiocytes and hepatocytes. In both cases, presence of the variant was associated with delayed disease progression. In a multi-variate Cox regression, the AE2 variant rs2303932 (T/A) was an independent prognostic factor for disease progression in PBC under UDCA treatment, in addition to serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum albumin levels which are established surrogate markers of prognosis in PBC [112]. Most recently, a landmark genetic association study was published [332]. Associations with the risk of disease were unravelled for 13 loci across the HLA class II region, two SNPs at the interleukin 12 alpha (IL12A) locus, one SNP at the interleukin 12 receptor beta 2 locus, and one previously described SNP at the CTLA4 locus. Associations with more than 10 further loci were described. Various associations with other loci have been described in individual populations, mostly of limited size. However, the vast majority have not been confirmed in independent cohorts, and to date, none of the genetic associations described in PBC have been proven sufficiently [84, 88, 108].

Future genetic linkage studies in affected families as well as association studies in large cohorts of unrelated patients may disclose genetic variants conferring susceptibility or influencing progression and severity of disease. Such linkage studies are awaited for PBC [115].

It remains speculative whether the female preponderance (gender ratio up to 10:1) reflects an X-chromosome-linked locus of susceptibility. Alternatively, a protective role of Y-linked genes could be assumed, or just a gender-specific exposure to environmental triggers like cosmetics [116] or nail polishers [117], as discussed below. However, speculation on a pathomechanistic role for X chromosomal genes was supported by the observation of an increased frequency of X chromosome monosomy in PBC as well as in other autoimmune diseases. This increase in X chromosome monosomy might lead to haploinsufficiency for specific X-linked genes and thereby increase disease predisposition [118]. Case reports of PBC in patients with Turner syndrome (45, X0) also supported this hypothesis [119].

Estrogen signaling has also been proposed to play a role in the homeostatic proliferative response of cholangiocytes in PBC. Accordingly, studies on polymorphisms in estrogen receptor genes revealed associations with the disease, at least in some populations [120]. At the tissue level, cholangiocytes from PBC patients in the earliest disease stages (but not cholangiocytes from normal controls) express estrogen receptors [121]. Agents able to modulate estrogen-receptor-mediated responses (such as tamoxifen) have therefore been proposed as novel, BEC homeostasis targeting therapies, and case reports support this hypothesis [122, 123], but as yet, this potentially interesting therapeutic approach has not undergone formal assessment in clinical trials.

Most recently, altered expression of hepatic microRNA (miRNA) has been described in liver tissue of PBC patients [124]. Certain miRNA negatively regulate protein coding gene expression and may play a critical role in various biological processes. However, a causal link between altered miRNA expression and the development of PBC still remains unproven.

Environmental factors

Despite strong evidence for a genetic background in PBC, epidemiological studies have early suggested a role for environmental factors in triggering and/or exacerbating PBC [20, 125, 126]. A significant role for environmental factors was supported by the identification of geographic disease “hot spots,” as first reported in the northeast of England, using formal cluster analysis. The original UK analysis reported an increased frequency of PBC in former industrial and/or coal mining areas [127]. Another recent study from New York examined the prevalence of PBC and PSC near superfund areas and reported significant clusters of PBC surrounding toxic sites [128]. In synopsis, these observations gave rise to the hypothesis of a chemical environmental factor, potentially associated with contaminated land, which could either trigger disease or cause disease through a direct toxic effect [84]. This hypothesis would also provide one possible explanation for the tissue tropism of PBC if the toxin or toxins are excreted into bile (and thereby concentrated in the biliary tree) [84]. The observation that hormone replacement therapy and frequent use of nail polish are linked to the risk of developing PBC further supports the potential impact of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of PBC [117]. Smoking also seems to be a risk factor for PBC and has been demonstrated to accelerate progression [117, 129]. Associations of exposure to chemical environmental compounds and xenobiotics (including drugs, pesticides, or other organic molecules) with various human autoimmune diseases have been described as summarized in [86].

Xenobiotics may contribute to the pathogenesis of PBC by triggering autoimmune reactions. Different mechanisms for the induction of autoimmunity by xenobiotics have been proposed [86, 130]. A potential direct toxic effect of xenobiotics my cause cell death by apoptosis or oncosis, inducing the generation of immunogenic autoepitopes. In addition, chemical modification of native cellular proteins by removal and/or exchange of a hapten has been shown to change processing in antigen-presenting cells and may lead to the presentation of cryptic, potentially immunogenic peptides. Furthermore, xenobiotics may have the potential to modify host proteins to form neoantigens. Neoantigen-specific T cells and B cells, once primed, may cross-react with the formerly inert native autoantigens. In accordance with this hypothesis, Amano et al. [131] studied a number of xenobiotics with a structure similar to lipoic acid, a residue on the E2 epitope of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), the main autoreactive antigen identified in PBC so far in PBC. Replacement of lipoic acid by certain xenobiotics enhanced the reactivity of PBC sera against the PDC-E2 epitope. Particularly, one of the xenobiotics, 2-nonynoic acid, induced reactivity of PBC sera stronger than that of the native lipoic acid residue. Interestingly, the methyl ester of 2-nonynoic acid has a viol-/peach-like scent and is used as an ingredient in perfumes. It is ranked 2,324th out of 12,945 chemical compounds in terms of occupational exposure with an 80% female preponderance due to its use in cosmetics.

Infections

Among the environmental factors that have been suggested as potential causative agents in PBC, particularly different bacteria have been discussed. In early histologic lesions in PBC, non-caseating granulomas are observed, as seen in other granulomatous liver diseases including sarcoidosis [1], drug reactions, and, most interestingly, infections. Furthermore, non-caseating granulomas are unique to PBC when compared to other autoimmune pathologies. This has led to suspicion of a microbial basis for PBC [132]. In support of this hypothesis, certain bacteria were found to contain PDC components fully cross-reactive with the mammalian form. It was proposed that exposure to these homologues could trigger cross-reactive immunity. In favor of a bacterial etiology, recent data suggest that Toll-like receptor ligands induce an augmented inflammatory response in PBC. In combination, presence of cross-reactive antigens in a pro-inflammatory environment would theoretically be able to break tolerance [133, 134].

With this theoretical background in mind, early studies associating various bacteria with PBC re-attract interest: E. coli has been reported to be present in excess in the feces of patients with PBC. In addition, the incidence of urinary tract infections often induced by E. coli is high in PBC patients [73, 135], and history of urinary tract infections increases the risk of PBC [117]. Another microorganism that has been proposed as a candidate for the induction of PBC is Novosphingobium aromaticivorans [136]. Titers of antibodies against lipoylated bacterial proteins of this ubiquitous organism, which metabolizes organic compounds including estrogens, were 1,000-fold higher compared to those against E. coli in patients with PBC, but no antibodies were observed in a large cohort of healthy subjects. Lactobacilli and Chlamydia, which show some structural homology with the autoantigen (although reactivity against them is considerably less than that against either E. coli or N. aromaticivorans), have also been implicated as putative pathogens, as have Helicobacter pylori and Mycobacterium gordonae [137–140]. Recently, a case of PBC following lactobacillus vaccination for recurrent vaginitis was reported. The vaccine contained Lactobacillus salivarius, which exerts a high homology to the beta-galactosidase of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (LACDE BGAL266–280), and cross-reactivity of patients' autoantibodies against the human PDC-E2212–226 epitope and LACDE BGAL266–280 was found. Affinity to the Lactobacillus epitope was higher than to the native mammalian, suggesting that antimicrobial reactivity may have preceded that to the self-mimic [141]. However, the AMA status of this patient before repetitive lactobacillus vaccination could not be assessed and causal relation of lactobacillus exposure and development of PBC remains speculative also in this study.

Despite these intriguing associations, no compelling data have been provided to show that one individual infectious agent can reproducibly be detected in patients with PBC. Although attractive, the model of bacterial infections as cause of PBC is thus supported by little direct evidence. Further objective data are warranted, obtained either from prospectively followed cohorts or through case–control epidemiological approaches, confirming a role for bacteria in triggering PBC [84].

An alternative infectious agent has recently been proposed as trigger of PBC when a human retrovirus was identified both in liver tissue and hilar lymph nodes from PBC patients. EM analysis of liver tissue obtained from PBC patients revealed retrovirus compatible particles in BECs. In periportal lymph nodes, mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) was detected and correlated with aberrant distribution of PDC-E2 in perisinusoidal cells. Homogenates of these periportal lymph nodes also had the capacity to infect BEC cultures inducing marked phenotypic change, and this effect could be abolished by irradiation of the culture media, suggestive of an infectious agent [142, 143]. Retroviral infection hypothetically could cause BEC damage either through a direct viral cytopathic effect, through cross-reactivity between viral protein and self-PDC, a “molecular mimicry” model, or virus-induced apoptosis [84]. Retroviral infection would also provide explanations for some key phenomena in PBC. PBC can recur rapidly after transplantation with all of the clinical manifestations including the detection of AMA in serum [144], the aberrant expression of the AMA-reactive protein on BEC [145], and histologic evidence of disease in up to 45% of patients [146]. In this respect, the observation of an association of more potent immunosuppressive therapy following transplant and earlier and more aggressive recurrence of PBC [147] is also of interest. MMTV replication is regulated in part by a progesterone-responsive glucocorticoid regulatory element in the promoter region, offering an alternative explanation for the female preponderance seen with PBC [148].

These findings attracted attention in the field and were acknowledged by other investigators who pointed out the need for clinical trials with antiretroviral therapies [149]. Subsequently, in a small non-randomized pilot study, therapy with Combivir (lamivudine + zidovudine) improved inflammatory scores, normalized AP, and reduced bile duct injury in patients with PBC [150]. These findings await confirmation in a randomized, controlled trial.

Unfortunately, major findings of the outlined in vitro studies could not be reproduced by independent groups, and others raised concerns that these findings might mainly reflect contamination or technical artifacts [151]. In an independent study, a large number of sera of PBC patients and healthy controls did not show reactivity against MMTV encoded protein, and no detectable immunohistochemical or molecular evidence for MMTV was found in liver specimens or peripheral blood lymphocytes [152]. It was also speculated that beneficial effects of antiretroviral therapy could be partly explained by anti-apoptotic properties of nucleoside analogs [151, 153]. Furthermore, mechanisms by which human betaretrovirus would enter human cholangiocytes are also not identified.

A more recent study, however, strengthened the case for involvement of retroviruses in (immune-mediated) liver disease: Sera of 179 patients with diverse chronic liver diseases and 31 controls were tested for reverse transcriptase activity and presence of human betaretrovirus by polymerase chain reaction. Reverse transcriptase activity was detected in 73% of autoimmune hepatitis patients, 42% of PBC subjects, 35% of patients with viral hepatitis, 22% of liver patients without viral or autoimmune pathogenesis (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease), and 7% of control subjects. In polymerase chain reactions, 24% of PBC samples were positive for human betaretrovirus compared to 13% in autoimmune hepatitis, 5% in other liver diseases, and 3% in non-liver disease control subjects [154]. If these data can be confirmed, a retroviral compound in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated and viral liver disease seems attractive, though not specific for PBC. Thus, despite some intriguing findings, the pathogenetic relevance of retroviruses in the development of PBC remains enigmatic.

Others

Appendectomy, other abdominal surgeries, and tonsillectomy were significantly more frequently reported in patients with PBC in an epidemiological study in North America [155]. However, an earlier population-based case control study conducted in England did not show such associations [156]. More recently, another case–control study provided evidence that there was at least no association between PBC and the occurrence of appendectomy and pointed out the selection bias present in the previous study done in North America [157]. The linkage to appendectomy was theoretically attractive, since a PBC-specific immune response to the highly conserved caseinolytic protease P of Yersinia enterocolitica in 40% of patients with PBC was reported [158]. It is noteworthy, that infection with Y. enterocolitica is one of the major causes of acute terminal ileitis mimicking acute appendicitis [159].

Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is a phenomenon of dysregulated immune response against self-antigens. If persistent, this can result in inflammatory tissue damage. The immune response to antigens is tightly controlled by various pathways whose deregulation may lead to autoimmune responses. Genetic predisposition and environmental factors affect the susceptibility to such deregulation [86].

Tolerance against self- antigens is achieved in the lymphopoietic differentiation in early life, when high-affinity self-reactive lymphocytes are deleted in the primary lymphoid organs, thymus, and bone marrow. Second, in the periphery, there is activity of a subset of T lymphocytes, T regulatory cells (Tregs), which are dedicated to regulatory function expressing the CD4 and CD25 surface markers and the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3). Additional backups along the maturation process of lymphocytes are described, limiting the induction and expression of autoimmunity. These regulatory mechanisms include apoptosis pathways, cytokines and their receptors, chemokine signaling, T cell–T cell interactions, and intracellular signal transduction. Accordingly, loss of self-tolerance could involve multiple faults, most of which are of genetic origin.

It is worth mentioning that autoimmunity, defined by the presence of autoantibodies and autoreactive lymphocytes, does occur naturally. It appears that such naturally occurring autoantibodies and autoreactive lymphocytes are modulators for the suppression of early infections, clearance of apoptotic bodies, immune surveillance against cancer cells, among others, as reviewed in [160]. In this not yet completely unraveled system regulating immune response, the mechanisms responsible for the development of autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases remain enigmatic.

Imbalance of T cell regulation can be sufficient on its own to initiate or propagate autoimmunity in various chronic inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or rheumatoid arthritis. In line with this concept, recent transgenic animal models highlight the role of T cell regulation in the development of autoimmune diseases. For instance, IL-2 receptor−/− mice were shown to develop severe anemia and IBD [161], possibly due to the decreased numbers of Tregs facilitating autoimmune reactivity in the presence of proliferating (and probably, activated) T-cells. Absence of the IL-2 receptor in these animals leads to proliferation of T cells and decreased numbers of Tregs.

Another hypothesis is the concept of molecular mimicry based on the similarity of pathogen and host antigen-derived epitopes recognized by the immune system [162, 163], which render bacteria and viruses candidates for the induction of autoimmune disease. This mechanism has first been suggested to be responsible for the development of rheumatic fever, and though this could never be confirmed, there is evidence suggesting associations of infectious triggers for several systemic autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis [164, 165], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [166], and rheumatoid arthritis [167]. Autoantigens are unable to elicit a primary immune response themselves. However, T cells stimulated by a pathogenic cross-reactive epitope can recognize such targets. As a prerequisite, the pathogen-derived cross-reactive epitope has to be sufficiently different from the host-derived epitope. The role of infectious agents in development of autoimmunity has recently been reviewed elsewhere [168, 169].

Xenobiotics represent another environmental factor foreign to human organisms, and may induce immune reactions or have the potential to modify host proteins and render them more immunogenic. Examples include drugs, pesticides, or other organic molecules. A number of xenobiotics have been associated with several human autoimmune diseases. Chemicals which were linked to autoimmunity include mercury in glomerulonephritis [170], hydrazines in SLE [171, 172], iodine in autoimmune thyroditis [173], and halothane in drug-induced hepatitis [174, 175]. Halothane-induced liver disease occurs when susceptible individuals develop immune response against trifluoroacetylated (TFA) self-proteins upon halothane exposure. Noteworthy is that the lipoylated E2 domain of human PDC is also recognized by anti-TFA [176].

As a further trigger of autoimmunity, it has been speculated that increased cell turnover or, more specifically, increased cell apoptosis may lead to exposure of otherwise rarely exposed antigens and induction of immune response to self. Enhanced apoptosis has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases, including Hashimoto's thyreoiditis [177]. This hypothesis would also provide an appealing explanation for the tissue specificity of most autoimmune reactions despite the often ubiquitous expression of the targeted autoantigen.

However, apoptosis is genuinely designed to actually prevent inflammatory reactions to cell death, and ingestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages induces the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10, both promoting the expression of Tregs, suppressing an autoimmune response during apoptosis [160]. While apoptosis per se is a non-inflammatory process, it can lead to abnormal antigen presentation, especially of previously sequestered antigens. Evidence for a role in the development of autoimmune disease, however, is limited and particularly in organ-specific autoimmune diseases [178]. Whether apoptosis-related mechanisms lead to PBC is unclear [179], but cholangiocytes in PBC may undergo increased cell turnover, e.g., due to metabolic stress, resulting in an inadequate immune response [179]. Strikingly, BECs in patients with PBC seem to be under significantly increased apoptotic stress compared to healthy controls or patients with other causes of inflammatory reactions in the liver, such as chronic viral hepatitis or PSC [180–182]. However, it is yet to be elucidated whether this effect is really a cause of autoimmunity in PBC or rather the consequence of increased inflammation.

Loss of self-tolerance in PBC

PBC is associated with other autoimmune diseases, both within individuals and among families, reflecting the “clustering” characteristic for autoimmunity [183]. PBC was one of the first conditions in which the presence of autoantibodies in the serum was identified and in which the antigen specificity of this autoreactive response was characterized [5]. It is therefore often referred to as a “model autoimmune disease.” The predominant autoreactive antibodies in PBC are AMAs, which, with a high sensitivity and specificity, are virtually diagnostic for PBC when detected in serum. The so far identified targets of AMA are all members of the family of 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenase complexes (2-OADC). This includes the E2 subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), the branched chain 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenase complex (BCOADC-E2), the 2-oxo-glutaric acid dehydrogenase complex (OGDC-E2), and the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase binding protein (E3BP) [184], all localized within the inner mitochondrial matrix, catalyzing oxidative decarboxylation of keto acid substrates. The targeted E2 subunits all have a common N-terminal domain containing single or multiple attachment sites for a lipoic acid cofactor to lysine. Previous studies have demonstrated that the dominant epitopes recognized by AMA are all located within these lipoyl domains of the target antigens [185–188]. The autoreactive CD4 and CD8 T cells infiltrating the liver in PBC recognize the same PDC-E2 domain (peptides 159–167 and 163–176) [189, 190], and the same accounts for the dominant autoreactive B cells [191]. CD8 T cells isolated from livers of patients with PBC have been found to exert cytotoxicity against PDC-E2 pulsed autologous cells (peptides 159–167) [192], supporting the hypothesis of a T cell response contributing to bile duct injury in PBC.

It remains a mystery how PDC-E2 and other epitopes localized to the inner membrane of mitochondria become targets of autoimmune injury in PBC. One working hypothesis, largely enforced by the Gershwin group, is that modifications of 2-OADC by xenobiotics may alter these self-proteins to cause a breakdown of tolerance facilitating an autoimmune response.

This group identified a 12-amino acid residue peptide of the inner domain of PDC-E2 containing the lipoic acid cofactor carrying 173 lysine to elicit the strongest reactivity of purified sera from PBC patients when compared to a number of other potential epitopes. They subsequently could show that reaction of the same PBC sera was significantly increased by lipoylation of this epitope [193].

Subsequently, the identified PDC-E2 residue was modified by replacing lipoic acid with a series of similar but distinct synthetic structures. Following this modification, PDC-E2-specific autoantibodies from patients with PBC reacted with higher affinity to the modified epitopes than to the native PDC-E2 peptide. The structure inducing maximal affinity was demonstrated to be derived from 2-nonynoic acid, a compound widely used in cosmetics [116].

Xenobiotics, in studies of the same group, were also shown to induce PBC-like features in different animal models. Immunization of rabbits with 6-bromohexanoate (6BH), coupled to bovine serum albumin (BSA), led to break of tolerance to PDC-E2 as judged by the detection of AMA [194]. In guinea pigs, immunization with the compound 6BH–BSA led to the development of histological lesions typical of autoimmune cholangitis with the concurrent appearance of AMA, albeit with a long latency of 18 months [195]. Most recently, these efforts resulted in the development of an inducible animal model of PBC in C57BL/6 mice. In these animals, 2-octynoic acid coupled to BSA after a short follow-up of 8–12 weeks induced manifest autoimmune cholangitis, typical AMA, increased liver lymphoid cell numbers, an increase in CD8 liver-infiltrating cells, and elevated levels of serum tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ. Remarkably, unlike many other animal models of PBC, the reported immunogenic response was liver-specific, and no inflammation was found in organs other than the liver [196]. However, the model still has disadvantages, e.g., lacking the development of fibrosis.

An alternative but complementary concept for loss of self-tolerance in PBC is the idea of underlying immune deficits. This concept is based on clinical and experimental evidence. PBC exhibits clustering with various autoimmune disorders, both within individuals and family. Moreover, in PBC there are reduced levels of Tregs suppressing immune reactions against self [197]. In two genetically manipulated mouse strains, spontaneous occurrence of a PBC-like lymphoid cholangitis together with positivity for anti-PDC-E2 within several weeks of life was reported when either transgenic expression of a dominant negative TGF-β II receptor (dnTGF-β RII) or transgenic disruption of the IL-2 receptor alpha that is highly expressed on Tregs was performed [198, 199]. Interestingly, B cells had a suppressive effect on the inflammatory response in the dnTGF-β RII model of PBC [200]. A role for IL-2 signaling defects in development of PBC was supported by a report of a PBC-like liver disease in a child with inborn deficiency of IL-2 receptor alpha [201]. An additional mouse model of NOD.c3c4 was described to develop autoimmune biliary disease and was found to test AMA-positive [202]. In all models outlined here, the biliary epithelium is infiltrated with CD4 and CD8 T cells, whereas granulomas and eosinophilic infiltration are seen only in NOD.c3c4 mice.

Conversely, IL-17 has recently been shown to be involved in various autoimmune disorders. In PBC liver tissues, density of IL-17(+) CD4 lymphocytic infiltration (Th17) was higher than in healthy liver. Although enhanced density of Th17 cells is not specific to PBC, it is in line with the observation of the decreased number of Tregs and may illustrate the counterplay of Tregs and Th17 cells in PBC [203].

Pathogenetic model

There has been impressive progress in unraveling pathogenetic factors of PBC over the past decade. In favor of a genetic background, an outstanding concordance rate among monozygotic twins has been identified, as well as various genetic associations. Clustering of distinct HLA alleles and, among others, allelic variations of TNFα, CTLA-4, and anion exchanger 2 (AE2), respectively, have been described. In addition, there is compelling evidence for an environmental factor required for the development of PBC. Xenobiotics capable of modulating mammalian proteins to form neoantigens have been shown to induce pathologies resembling PBC in animal models. Furthermore, various infectious agents have been associated with PBC in humans, although direct experimental evidence for their role in the pathogenesis is limited. Lastly, disruption of AE2 [204] and genes involved in the regulation of immune response, such as the TGF-β II or IL-2 receptor or the AE2, gives rise to histologic and serologic changes mimicking PBC in different animal models and may be contributing to susceptibility for PBC in human.

However, a common causative pathway to PBC, if it exists, could not yet be identified, and it is still controversial which of the outlined factors predispose most to PBC. It may well be speculated that the search for “the cause” of PBC might lead into the dark, and the identified pathogenetic factors may contribute to a different extent in each patient. Why should the cause of PBC not be variable as is the clinical picture? The latter is highly variable: We define PBC today as the presence of cholestasis and AMAs, but only 90–95% of patients are AMA-positive and some AMA-positives hardly develop PBC. Most patients respond to UDCA treatment, but one third does not and disease progression is highly variable, to mention only the most obvious variabilities. The clinical picture that, by convention, we call PBC may well emerge from an individual composition of the described and other pathological factors.

Jones [84] suggested a model of PBC development distinguishing “upstream” from “downstream” events. “Upstream” in this model refers to the causes of BEC loss, ductopenia and cholestasis, which are unique to PBC (and probably unique to each individual patient) and include genetic and toxic factors, infectious agents, and immune-mediated events. “Downstream” of these initiating mechanisms, nonspecific pathologic events occur resulting in bile duct damage, hepatocyte injury, inflammation, and fibrosis independently of the primary -individual variable- cause. “Downstream” events such as hydrophobic bile salt retention aggravate the underlying injury, further promoting hepatic and cholangiocellular damage [205].

This pathogenetic model provides an explanation for the limited efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs in PBC. Agents such as prednisolone, in the treatment of PBC of limited efficacy, may mainly affect upstream mechanisms. In clinical trials, these agents have, however, largely been evaluated in relatively advanced, symptomatic patients. In these individuals, downstream processes may have become predominant.

The balance of evidence in PBC remains strongly in favor of an autoimmune process in which the autoreactive attack is directed at epitopes within self-PDC-E2. The following factors can, in principle, contribute to this breakdown of self-tolerance and have been suggested for PBC:

There is strong and compelling evidence to support molecular mechanisms of cross-reactivity between the PDC-E2 lipoic acid co-factor and environmental xenobiotics inducing auto-immunogenity of modified self-PDC-E2. Animal modeling data would argue that a cross-reactive B cell response induced to xenobiotic-modified self-PDC can, through a process of epitope spreading driven by antigen-specific cross-reactive B cells, translate into the breakdown of T cell tolerance responsible for the effector T cell mechanisms thought to be directly responsible for BEC loss. The clinical implication of this observation again is that immunomodulatory approaches to therapy should play a role particularly in the earliest stages of PBC.

Alternatively or in addition, molecular mimicry mechanisms with cross-reactivity between self-PDC and bacterial or potentially viral structures may support or induce breakdown of tolerance.

Most data on genetic associations with disease point to loci or genes involved in immune function. Altered regulation of self-tolerance can possibly support or induce immune reaction against self-PDC-E2, expressed normally or aberrantly by BECs.

Primary events of cholangiocellular apoptosis or cell damage have been suggested that could lead to aberrant presentation of self-antigens or create an inflammatory environment potentially triggering immune dysregulation. Suggested mechanisms include metabolic stress, possibly triggered by dysfunction of transporters involved in cell maintenance like AE2. This mechanism was suggested [179] based on the finding that an AE2 variant is a strong and independent prognostic factor for disease progression in PBC under UDCA therapy [112]. Furthermore, secretion of directly toxic environmental compounds into the bile or viral infection would trigger cholangiocellular damage.

Finally, functional and morphological changes in BECs, either as an associated process to outlined factors or as part of the homeostatic mechanism designed to retain BEC function, may lead to altered self-recognition.

Each of these mechanisms may occur simultaneously or sequentially and, to a variable extent, result in the breakdown of tolerance and immune-mediated liver pathology. Once an autoimmune reaction is initiated, various vicious cycles are conceivable. Inflammatory reaction secondary to loss of tolerance will lead to further cholangiocellular damage and apoptosis, increasing presentation of (altered) self-PDC and increase autoreactivity. Once bile duct loss and cholestasis are established, retention of bile salts and other toxic compounds perpetuates damage to BECs and subsequently to the entire liver. Maintenance of these vicious cycles may be supported by an immune system that is genetically dysregulated and insufficiently capable of suppressing autoimmune reactions.

The outstanding paradox in PBC pathogenesis remains the tissue tropism of the immune attack on the small intrahepatic bile ducts, although the mitochondrial targets are ubiquitously expressed proteins. An increased vulnerability of the primarily affected BECs therefore is a prerequisite in the pathogenesis of PBC. Staining of BECs from PBC livers with monoclonal antibodies against the mitochondrial PDC-E2 autoantigen showed a specific reaction at the apical surface which was not found in controls [206, 207]. Other non-PBC-related mitochondrial proteins show the expected cytoplasmic pattern [208]. It was subsequently demonstrated that the apical staining is due to a complex between (auto-)antimitochondrial IgA and PDC-E2, giving rise to speculations that IgA might be a player in the immune-mediated destruction of BECs [209, 210]. Apoptosis of BECs has been proposed as a cause of aberrant neoantigen presentation, responsible for activation or attraction of autoreactive T lymphocytes or antibodies. Unlike other cell types [211] for which autoantibody recognition of PDC-E2 is abrogated during apoptosis, probably by glutathiolation of the lysine–lipoyl moiety of PDC-E2, the antigenicity of PDC-E2 persists in the apoptotic BECs in which glutathiolation does not occur [211, 212].

The course of apoptotic markers in patients with PBC peaks in the middle stages of the disease (stages II–III) rather than in earlier stages. This could solely support a role of apoptosis as a trigger for loss of self-tolerance, with probably only a little number of cells being affected rather than being the main initiating event in PBC. In a putative positive feedback loop, apoptosis, autoreactive T cell response, cholestatic bile salt retention, and failed replicative homeostasis may result in the destruction of BECs and bile duct structures.

Therapy

UDCA treatment

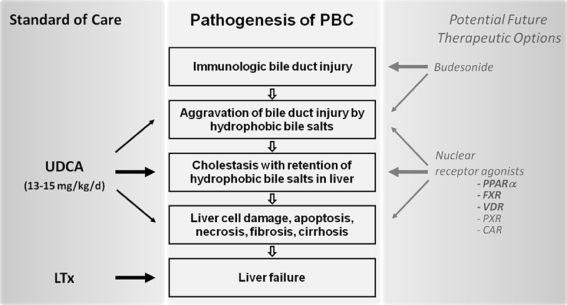

UDCA has been administered in Chinese traditional medicine as a remedy for liver diseases and other disorders in the form of black bear's bile since the time of the T'ang dynasty (618–907 ad) and was reestablished in the late 1950s in Japan as a choleretic agent with gallstone-dissolving and anticholestatic properties. In the Western literature, the beneficial effects of UDCA on serum liver tests for patients with hepatic disorders were first reported in the 1980s [213, 214], and UDCA has since been established for the treatment of PBC. Today, it is the only FDA-approved drug and standard therapy for PBC. UDCA was shown to improve serum biochemical markers such as bilirubin, AP, γGT, cholesterol, and IgM levels [215–220]. UDCA may slow down histologic progression to liver cirrhosis [219, 221], improve quality of life, survival free of transplant, and overall survival [11–14, 222]. It is safe and side effects are few [223]. However, the mechanisms of action of UDCA in chronic cholestasis remain enigmatic [224]. About a third of patients is not sufficiently controlled with UDCA monotherapy [12, 13], which drives the search for additional therapeutic approaches (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of standard therapy and promising future therapeutic options in PBC with respect to their action in the pathophysiologic chain of PBC. UDCA in a dose of 13–15 mg per kg body weight per day, administered in either one dose or divided into two administrations per day, is the only FDA-approved drug and the cornerstone in PBC therapy. Liver transplantation (LTx) is performed for liver failure in end-stage disease. The most advanced database for future therapeutic consideration is available for budesonide. Though speculative, current preliminary data suggest a future role for agonists to certain nuclear receptors: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARα), farnesoid x receptor (FXR), vitamin D receptor (VDR), pregnane x receptor (PXR), and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR)

Pathophysiologic rationale for UDCA therapy

Cholestasis leads to retention of bile salts and other potentially toxic constituents of bile not only systemically but particularly in hepatocytes. This promotes hepatocellular damage and, in a chronic state, can induce the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver.

As recently summarized by Paumgartner and Pusl [225], the general biochemical and physiologic principles in treating cholestatic liver disease can be broken down to “(1) reduction of hepatocellular uptake of bile salts and other organic anions; (2) stimulation of the metabolism of hydrophobic bile salts and other toxic compounds to more hydrophilic and less toxic metabolites; (3) stimulation of orthograde secretion into bile and (4) stimulation of retrograde secretion of bile salts and other potentially toxic cholephils into the systemic circulation for excretion by the kidney; (5) protection of injured cholangiocytes against toxic effects of bile salts; (6) inhibition of apoptosis caused by elevated levels of bile salts; and (7) inhibition of fibrosis” [225].

Treatment with UDCA addresses most of these postulated principles as recent clinical and experimental data suggest [224, 226, 227]. Still, no relevant effect of UDCA on (1) bile salt uptake and (2) bile salt metabolism [228, 229] has been demonstrated in man.

Hepatic secretion

When patients with PBC are treated with UDCA, serum levels of bilirubin [216] and endogenous bile salts [230] decrease. This effect of UDCA seems to be mediated by posttranscriptional rather than transcriptional mechanisms, as mRNA levels of key transporters like the conjugate export pump, ABCC2/MRP2, and the bile salt export pump, ABCB11/BSEP, are not affected by UDCA in man. Enhanced hepatic protein levels of BSEP, but not MRP2, have been observed under UDCA treatment in patients with gallstones [228] and may contribute to improved elimination of bile salts [231]. In an animal model of cholestasis, UDCA increases the density of Bsep and Mrp2 in the canalicular membrane of the rat by stimulating transporter targeting and insertion into the membrane [232] by a cooperative protein kinase C α/protein kinase A-dependent mechanism [224, 233–235]. An integrin-dependent dual signaling pathway involving mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) Erk 1/2 and p38MAPK has been shown to mediate UDCA-induced canalicular BSEP insertion in normal [236, 237], but not cholestatic [238] hepatocytes. Whether UDCA-induced kinase-mediated phosphorylation of carriers contributes to enhanced canalicular transporter density and activity needs to be studied in more detail [224, 235, 239].

Dilution of bile and the flushing of bile ducts were postulated as important functions of cholangiocellular bile formation [225]. In PBC, expression of the hepatic AE2 and biliary bicarbonate secretion by AE2 are impaired [240, 241]. UDCA stimulates both AE2 expression [242] and bicarbonate secretion [241].

Retrograde secretion of bile salts and other potentially toxic cholephiles

As an adaptive mechanism during cholestasis, basolateral conjugate transporters such as ABCC3/MRP3 are upregulated and cholephiles such as bilirubin glucuronides, which are not adequately secreted into bile, can leave the liver cell via the basolateral route. In contrast to the postulated increase in retrograde secretion [228], UDCA diminishes basolateral efflux due to the effective stimulation of orthograde secretion of potentially toxic compounds into the bile.

Protection of cholangiocytes

Bile, with its high concentration of hydrophobic bile salts, exhibits extracellular cytotoxicity in vitro, but does not cause cholangiocyte injury under physiological conditions. In PBC, inflammatory bile duct injury may be aggravated by hydrophobic bile salts. Two mechanisms have been discussed by which UDCA protects the biliary epithelium against toxic effects of bile, i.e., relative reduction of hydrophobic bile salts and enrichment of phospholipids in bile. When administered at recommended doses of 13 to 15 mg/kg/day, UDCA content may rise up to 50% of total bile salts [243] and to an even higher percentage when the dose of UDCA is increased [244, 245]. In consequence, bile composition is shifted towards less toxic and less hydrophobic bile salts.

UDCA administration in patients with gallstones increases expression of MDR3, a phospholipid flippase, in the liver [228]. This might explain the stimulation of biliary phospholipid secretion by UDCA, as described in patients with PSC [246]. Secreted phospholipids form mixed micelles with bile salts, thereby mitigating their toxic effects on cholangiocytes.

Inhibition of apoptosis

Hydrophobic bile salts induce hepatocellular apoptosis [247–249] by death receptor-dependent [250, 251] and -independent [252, 253] mechanisms, an effect that may become relevant when bile salts accumulate in the liver in cholestatic states. UDCA exerts anti-apoptotic effects in experimental in vivo models [247, 249, 252] as well as in vitro in primary human hepatocytes [254]. This anti-apoptotic effect may contribute to the alleviation of liver injury during UDCA treatment.

Inhibition of fibrosis

Release of chemokines and cytokines by injured cholangiocytes and infiltrating inflammatory cells [255] as well as hepatic stellate cell proliferation induced by bile salts may play a role in fibrogenesis [256]. UDCA has been reported to delay development of severe fibrosis and cirrhosis in PBC [221]. This may be related to the aforementioned anticholestatic and anti-apoptotic effects rather than direct antifibrotic effects of UDCA. The bile salt derivatives 6-ethyl CDCA (6-ECDCA) and nor-UDCA inhibit fibrosis in the bile-duct-ligated mouse. While 6-ECDCA seems to mediate this antifibrotic effect via farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and small heterodimer partner (SHP) [257], the mechanism of action of nor-UDCA remains yet unclear [258].

Immunomodulatory properties

of UDCA have been controversially discussed in the past [259–262]. The glucocorticoid receptor in rat hepatocytes is activated by UDCA in a ligand-independent way, whereas suppression of IFN-γ-induced MHC class II expression was found to be glucocorticoid-receptor-dependent [263]. It remains to be defined whether glucocorticoid receptor activation is unique to UDCA, and thus therapeutically relevant, or might be shared by endogenous bile salts.

Comprehensive reviews on molecular actions of UDCA have been published in the recent past [205, 224, 264–266].

UDCA treatment in clinical practice

UDCA is currently considered the mainstay of therapy for PBC [28, 29]. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials have consistently shown that UDCA, administered today in standardized doses of 13 to 15 mg/kg/day, improves serum biochemical markers including bilirubin [215–218, 220], an important prognostic marker in PBC [267]. A number of studies demonstrated an improvement of histological features by UDCA. In a combined analysis of four clinical trials including a total of 367 patients [268] and in an independent in 103 patients [221], UDCA therapy was associated with delayed progression and a marked decrease in progression rate from early-stage disease to late histologic stages. Despite these effects on disease progression and severity, the assessment of the effect of UDCA treatment on long-term survival has been more difficult. A combined analysis of three randomized controlled trials including 548 patients in total treated with UDCA for up to 4 years revealed improved survival free of liver transplantation in patients with moderate or severe disease [222]. Another combined analysis of five studies, all with a follow-up of at least 4 years, quantified the reduction in the risk of death or liver transplantation in patients treated with UDCA to 32% [269]. A long-term follow-up study in a cohort of 225 patients, in part overlapping with the aforementioned analyses, reported 10-year survival without liver transplantation to be significantly higher in UDCA-treated patients compared with survival predicted by the Mayo model [270]. Recent long-term trials from France, Spain, and The Netherlands have shown comparable results [11–13, 271]. The survival rate of patients in early stages of the disease who biochemically responded to therapy was similar to that in the control populations. “Response” here is defined as a decrease in AP to <40% of pretreatment levels or normalization at 1 year (Barcelona criteria) [12] or serum bilirubin <1 mg/dl, AP ≤ 3 × N and AST ≤ 2 × N after 1 year of UDCA treatment (Paris criteria) [13, 14]. An additional non-randomized controlled study from Greece confirmed that in most patients with PBC treated with UDCA (particularly those who are in early stage of disease), the 10-year survival is comparable to that in the general population [272]. Despite these intriguing findings, the beneficial effects of UDCA on survival have repeatedly been questioned: A large randomized Swedish trial failed to confirm an effect of UDCA on disease progression and survival at a dose of approximately 8 mg/kg/day [273]. It was concluded from this and other studies that doses of UDCA lower than 10 mg/kg/day are of little benefit. In the follow-up of patients in a US [274] and a Canadian trial [217], UDCA had no significant influence on incidence of endpoints liver transplantation or death. Also, a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials could not confirm a significant effect of UDCA on survival and incidence of liver transplantation [275]. In this meta-analysis, however, six studies with only 2 years of follow-up were included, as were two studies administering UDCA at low doses of 10 mg/kg/day or less. Other meta-analyses suffered from similar shortcomings [276, 277] and may therefore have missed a beneficial effect of UDCA. Accordingly, meta-analyses which only included long-term trials with follow-up of at least 2 years and those using an effective dose of UDCA of more than 10 mg/kg/day verified that treatment with UDCA significantly improves quality of life and transplant-free survival and delays histologic progression in early-stage patients [278, 279]. Current guidelines therefore recommend to treat PBC with UDCA using doses of 13 to 15 mg/kg/day and to start treatment early [28, 29, 280].

About two thirds of patients treated according to these recommendations respond adequately as defined by the Barcelona or the Paris criteria and may have a normal life expectancy. The most recent study from The Netherlands comprising 375 patients with a mean follow-up of 9.7 years again stressed the importance of early treatment showing a clear survival benefit for patients treated in early stages of disease with normal serum bilirubin and albumin levels at the start of therapy [14].

For the remaining one third of patients who fail to achieve biochemical response according to Paris and Barcelona criteria or who are at an advanced histological stage at start of medical treatment, therapeutic options are limited to date and novel approaches are needed.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents have been evaluated for therapeutic use in PBC. In a 3-year, placebo-controlled trial including 36 patients with PBC, prednisolone significantly improved serum AP levels, IgGs, and AMA and diminished deterioration of liver histology, whereas bone loss was aggravated [281]. Combination of UDCA and prednisolone in comparison to UDCA alone resulted in a significant improvement of histological features [282]. It is yet unclear whether increased expression of AE2 isoforms contributes to the beneficial effect of combined treatment with UDCA and corticosteroids in PBC. Experimentally, enhanced expression of alternative AE2 isoforms and enhanced transport capacity for bicarbonate in human cholangiocytes and in a hepatocyte cell line were demonstrated [283]. AE2 expression and biliary bicarbonate secretion is usually diminished in PBC [241].

Serious side effects of long-term glucocorticoid treatment may outweigh the potential benefit. In this respect, the introduction of budesonide, a nonhalogenated corticosteroid with an extensive first-pass metabolism has been a promising innovation. A 2-year controlled double-blinded trial included 39 patients with early-stage PBC and compared treatment with UDCA plus budesonide against UDCA plus placebo. Combination therapy improved biochemical and histological features and reported only few corticosteroid-related side effects [284]. These promising results, however, could not be confirmed in a subsequent study from the Mayo Clinic. Here, adding budesonide for 1 year in 22 patients with suboptimal response to UDCA alone had only marginal effects on serum bilirubin and AP levels. In contrast, the Mayo risk score increased and there was a significant worsening of osteoporosis [285]. This open trial, however, included late-stage patients, which may in part explain the disappointing results. As found in a short-term pharmacokinetic study, administration of budesonide to cirrhotic PBC patients leads to high plasma levels of budesonide associated with serious adverse effects and should therefore be avoided [286]. A Finish study [287] included only patients with stages I to III (n = 77) in a 3-year randomized trial and used a lower dose of budesonide. The effects of budesonide plus UDCA were compared to UDCA alone. A significant improvement of histological features was observed in the combination group on top of the beneficial biochemical effects of UDCA alone. Long-term controlled trials are required to define whether combination of UDCA with budesonide provides a significant benefit in patients with early-stage PBC inadequately responding to UDCA monotherapy.

Other immunosuppressive agents including azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate and drugs with antifibrotic properties including penicillamine, colchicine, and silymarin have not been shown to markedly improve the natural course of the disease or were associated with significant toxicity during long-term treatment [1, 288–296].

Novel pharmacologic approaches

Novel concepts for medical therapy of PBC, alone or in combination with UDCA, have recently been considered particularly for use in patients with incomplete response to UDCA. Among others, antiretroviral, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant approaches were evaluated.

A human betaretrovirus has been controversially debated as a potential pathogen in PBC as outlined above. An antiretroviral strategy has therefore been tested in PBC: Lamivudine in combination with zidovudine (Combivir) normalized AP and reduced bile duct injury in a 1-year pilot trial including 11 patients [150]. This finding still awaits confirmation by a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) agonist bezafibrate was reported to improve serum liver tests in PBC [297] and should undergo more extensive evaluation in patients with PBC with an incomplete response to UDCA.

Future anticholestatic strategies in PBC are targeted towards stimulation of transcription of key hepatocellular and cholangiocellular transporters in order to improve the secretory capacity of the cholestatic liver. First results of pilot studies using the FXR agonist 6-ECDCA are eagerly awaited.

Therapy of extrahepatic manifestations

Pruritus

UDCA is an accepted treatment of cholestatic pruritus in ICP (intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy). However, its effect on pruritus is variable in PBC [217]. At present, no convincing data for an antipruritic effect of UDCA in PBC are available [298].

Both peripherally acting pruritogens and central nervous dysfunction have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cholestatic pruritus [9]. According to these two concepts, most therapeutic interventions currently under study for cholestatic pruritus are either directed towards elimination of so far undefined pruritogens or modulation of central neurotransmission. The pharmaceutic options currently recommended include [29]: (1) anion exchange resins, such as cholestyramine and colestipol, which bind anions and amphipathic molecules and reduce their intestinal absorption and systemic accumulation. Despite extensive clinical experience, suggesting a beneficial effect in up to 90% of patients, no large clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of exchange resins [298]. In patients lacking adequate improvement, treatment with (2) rifampicin may be helpful [298–301]. Rifampicin is a semisynthetic antibiotic and as a potent pregnane X receptor (PXR) agonist leads to the induction of hepatic microsomal enzymes. Thereby, it may promote metabolism of potential pruritogens. As a third-line option, (3) opioid antagonists (naloxone, nalmefene, naltrexone) have been found to reduce itch severity in patients with PBC [298, 302–304]. (4) The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline [305, 306] has been reported to improve cholestatic pruritus in small clinical trials and has most recently been considered as a fourth-line treatment option [29, 280]. Other experimental approaches include 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor type 3 antagonists, cannabinoids, subhypnotic doses of propofol, plasmapheresis, albumin dialysis, and nasobiliary drainage in desperate cases, although adequate trials are lacking [29, 63]. Liver transplantation should be considered in serious cases in which all other strategies have failed, even if liver function is still conserved [29].

Fatigue

Specific medical therapies of fatigue associated with chronic cholestasis have not yet been defined. UDCA treatment seems to have no or limited beneficial effects on fatigue in PBC [217, 307]. Oral supplementation with antioxidants showed promising results in a pilot study, but had no beneficial effect in a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial [308]. Independent of the underlying disease, altered serotoninergic neurotransmission has been implicated in the development of fatigue [309]. The 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist ondansetron, however, did not significantly reduce fatigue compared with placebo in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial [310]. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors fluvoxamine and fluoxetine also failed to exert beneficial effects on fatigue in this patient group [311, 312].

In a series of 21 PBC patients with excessive daytime sleepiness [313], the centrally acting agent modafinil was investigated in an open-label study [314]. Significant improvement was seen in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores and fatigue severity as assessed by PBC-40 fatigue domain score, but the drug had to be stopped due to side effects in a considerable part of the patients before the end of the study.