Abstract

A case of presumed pontine capillary telangiectasia in an 18-year-old woman with a clinical diagnosis of basilar-type migraine is reported. Since both are very rare diagnoses, this case provides some evidence to suggest that pontine capillary telangiectasia might cause a clinical picture resembling basilar-type migraine.

Keywords: Basilar-type migraine, Pontine capillary telangiectasia

Background

Brainstem vascular malformations can be classified as arteriovenous malformations, venous malformations, cavernous malformations, or capillary telangiectasias. On pathological examination, capillary telangiectasias are a distinct type of vascular malformation, characterized by multiple thin-walled vascular channels, interposed between normal brain parenchyma [1]. The exact etiology of these telangiectasias, however, remains unclear. It has been postulated that telangiectasias are acquired lesions, caused by other underlying venous anomalies. This would explain the frequently found presence of an associated vein at autopsy [2]. Another possibility is a primary developmental lesion. Since the introduction of MR imaging, numerous case reports of presumed brainstem capillary telangiectasias have appeared; usually pathological confirmation is absent. The fact that most capillary telangiectasias are found incidentally on MR imaging confirms the suggested clinically benign course in general [3], although a histopathologically proven, clinically aggressive case in an infant has been described [4]. We performed a PubMed search of the literature and found 26 cases to date [5–8]. All but one of these cases were thought to be symptomatic, including symptoms of vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, ataxia, limb paresthesias, and monocular ptosis.

Basilar-type migraine, previously called basilar migraine or Bickerstaff migraine, is a migraine variant first described by Bickerstaff in 1961 [9]. Being a very rare migraine variant, the exact incidence and prevalence are unknown. Although various criteria for the diagnosis have been applied over the years, fully reversible symptoms resulting from brainstem dysfunction are essential for the diagnosis. A recent study found the median age of onset to be 17 years and a female-to-male ratio of 3.8:1 [10].

Case

An 18-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with a history of unilateral headaches, accompanied by phonophobia, but no photophobia, nausea, or vomiting. These headaches had increased in frequency over the last 6 months from once per year to about three times per week, typically lasted several hours, and were alleviated by sleep. The headache was frequently preceded by visual symptoms, such as flickering or black spots, in both visual fields. The patient had not used painkillers for these attacks, because in her opinion, these headaches were not severe enough to justify the use of medication. Furthermore, this patient experienced a single episode of vertigo, followed by sudden loss of consciousness with a duration of about 10 min. No jerks, urinary incontinence, or tongue bite were present. On regaining consciousness, no confusional state was present, but patient noted the most terrible headache ever. Several days later, an attack of vertigo without hearing loss occurred, with alternating paresthesias in all limbs, followed by the same terrible headache. For these different—more recent—attacks, she had taken 1,000 mg of acetaminophen. This patient had no previous medical history and did not use any other medication. The family history was negative for migrainous headaches. Neurological examination revealed no abnormalities.

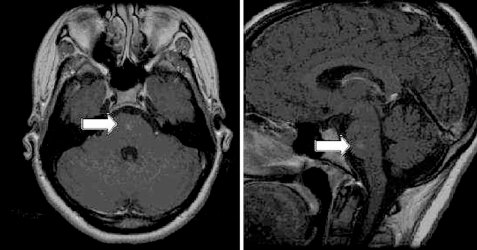

A clinical diagnosis of basilar-type migraine was made, since the patient fulfilled the International Headache Society (ICHD-II) criteria [11]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed focal areas of hyperintensity in T2-weighted spin echo images, hypointensity in T2*-weighted gradient echo images, and enhancement in postcontrast T1-weighted images (Fig. 1). These radiological findings are consistent with pontine capillary telangiectasia [2]. Following these MR findings, the diagnosis was revised to secondary headache attributed to cranial vascular disorder (ICHD-II 6), since one of the criteria for basilar-type migraine is that it cannot be attributed to another disorder. She was treated with propranolol 80 mg per day as prophylactic treatment and acetaminophen 1,000 mg during attacks. During follow-up, she reported excellent response to the propranolol, with no new basilar-type migraine attacks for 12 months.

Fig. 1.

Postcontrast axial and sagittal T1, arrows pointing towards MR-suggested capillary telangiectasia

Discussion

Although no pathologic confirmation is available in our patient, we believe the radiological abnormality found on MRI to be a capillary telangiectasia. This is supported by the absence of significant changes in a follow-up MRI scan. The association with clinical symptoms remains unproven, although a clinical picture of “peculiar attacks of prolonged loss of consciousness” due to pontine telangiectasia has been described in the literature [12]. Another paper describes a case of basilar-type migraine associated with calcifications in the pontine tegmental nuclei [13]. As this case illustrates, MR imaging of the brain should be considered if a rare cause of primary or secondary headache is suspected on clinical grounds. Follow-up imaging seems only to be warranted in presumed symptomatic lesions, although the added value remains debatable, since no therapeutic interventions are available. Regarding preventive treatment for basilar-type migraine, some experts prefer divalproex-sodium or verapamil instead of propranolol because of the concern of limitation of compensatory vasodilatory mechanisms [14]. In our opinion no contraindication for propranolol exists in this patient because of the assumed causal relationship between the capillary telangiectasia and her clinical symptoms. With respect to acute treatment, there seems to be consensus against triptans because of concern over the potential for cerebral vasoconstriction and the uncertainty of the mechanism of basilar-type migraine [14], although evidence proving this causality is lacking. In conclusion, with this case report we provide some further evidence that pontine capillary telangiectasia might cause a clinical picture resembling basilar-type migraine.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Barr RM, Dillon WP, Wilson CB (1996) Slow-flow malformations of the pons: capillary telangiectasias? Am J Neuroradiol 17:71–78 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Mc Cormick PW, Spetzler RF, Johnson PC, Drayer BP (1993) Cerebellar hemorrhage associated with capillary telangiectasia and venous angioma: a case report. Surg Neurol 39:451–457 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lee RR, Becher MW, Benson ML, Rigamonti D (1997) Brain capillary telangiectasias: MR imaging appearance and clinicohistopathological findings. Radiology 205:797–805 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Huddle DC, Chaloupka JC, Sehgal V (1999) Clinically aggressive diffuse capillary telangiectasia of the brain stem: a clinical radio-pathologic case study. Am J Neuroradiol 20:1674–1677 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Morinaka S, Hidaka A, Nagata H (2002) Abrupt onset of sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus in a patient with capillary telangiectasia of the pons. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 111:855–859 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sanchez-Santos PJ, Yago-Escusa D, Sanz-Asin JM, Lopez-Lopez A (2008) Telangiectasia capilar pontina como incidentaloma en un estudio de resonancia magnetica cervical. Rev Neurol 46:561–562 [PubMed]

- 7.Scaglione C, Salvi F, Riguzzi P, Vergelli M, Tassinari CA, Mascalchi M (2001) Symptomatic unruptured capillary telangiectasia of the brain stem: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71:390–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Yoshida Y, Terae S, Kudo K, Tha KK, Imamura M, Miyasaka K (2006) Capillary telangiectasia of the brain stem diagnosed by susceptibility-weighted imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 30:980–982 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bickerstaff ER (1961) Impairment of consciousness in migraine. Lancet 2:1057–1059 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kirchmann M, Thomsen LL, Olesen J (2006) Basilar-type migraine: clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. Neurology 66:880–886 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.IHS (2009) Classification ICHD-II. Basilar-type migraine. http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/01.02.06_migraine.html

- 12.Cushing H, Bailey P (1928) Tumors arising from the blood vessels of the brain. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, IL

- 13.Mishra NK, Cereda C, Carota A (2008) Lifetime basilar migraine: a pontine syndrome? Headache 48:476–478 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Evans RW, Lipton RB (2001) Topics in migraine management: a survey of headache specialists highlight some controversies. Neurol Clin 1:1–21 [DOI] [PubMed]