Abstract

Objective

To examine the prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of written advance planning among patients with or at risk for dementia-imposed decisional incapacity.

Design

Retrospective, cross-sectional.

Setting

University-based memory disorders clinic.

Participants

Persons with a consensus-based diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (N = 112), probable or possible Alzheimer disease (AD; N = 549), and nondemented comparison subjects (N = 84).

Intervention

N/A.

Measurements

Semistructured interviews to assess durable power of attorney (DPOA) and living will (LW) status upon initial presentation for a dementia evaluation.

Results

Sixty-five percent of participants had a DPOA and 56% had a LW. Planning rates did not vary by diagnosis. European Americans (adjusted odds ratio = 4.75; 95% CI, 2.40-9.38), older adults (adjusted odds ratio = 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.07) and college graduates (adjusted odds ratio = 2.06; 95% CI, 1.33-3.20) were most likely to have a DPOA. Findings were similar for LW rates.

Conclusions

Although a majority of persons with and at risk for the sustained and progressive decisional incapacity of AD are formally planning for the future, a substantial minority are not.

Keywords: Mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer disease, durable power of attorney, living will

Alzheimer disease (AD) is associated with profound changes in cognition, behavior, and functional status. Affected persons progressively lose the capacity to think conceptually, solve problems, and plan ahead—all of that are critical components for making meaningful decisions about medical, financial, and other life affairs.1-3 One option for persons at risk for such cognitive impairment is to plan for a time when others will have to step in and make decisions on their behalf.

Persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early stage AD are uniquely positioned to plan for a range of decisional scenarios that will arise within the course of their illness trajectory. Advance planning refers to a range of formal and informal activities that are undertaken to communicate an individual’s preferences and wishes for the future; durable power of attorney (DPOA), and living wills (LW) are among the most widely recognized examples.4 Despite broad, cross-disciplinary support for the practice of appointing a future surrogate decision-maker and discussing with that person one’s beliefs, wishes and care preferences,5-7 little is known about the formal planning practices and behaviors of older adults who are exhibiting early cognitive changes. Focusing on those at heightened risk for dementia-imposed decisional impairment, the purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DPOA designation and LW completion among persons who met diagnostic criteria for MCI or AD upon initial presentation to a university-based Memory Disorders Clinic. Although mild forms of cognitive impairment may be increasingly diagnosed in private and community-based practice settings, we conducted this investigation in a research-oriented specialty clinic to ensure consistency in the application of diagnostic criteria.

METHODS

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this secondary analysis and waived the requirement for written informed consent.

Sample

The sample for this study was drawn from the participant registry of the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC). Individuals presenting to the Memory Disorders Clinic of the ADRC with complaints of memory or other cognitive impairment consent to and undergo a standardized clinical research evaluation consisting of a medical and neurological history and examination, psychosocial assessment, psychiatric interview, neuropsychological testing, and brain imaging. Comparison subjects are individuals who are recruited from the community to serve as cognitively normal study volunteers. All subjects must have an informant (e.g., spouse, sibling, or child) who has frequent interaction with them and can independently report on their functioning. Upon completion of the clinical research evaluation, data from all cases (including comparison subjects) are reviewed by a multidisciplinary research group to establish consensus regarding the diagnosis and to determine eligibility for enrollment into the ADRC registry.8

Participants in the current study included all individuals who consecutively presented at the Memory Disorders Clinic between January 1, 2000 and August 31, 2005, and were classified by the Consensus Conference research team as being eligible for the registry and as meeting criteria for a) a diagnosis of Probable or Possible AD,9 b) a diagnosis of MCI,10 or c) serving as a cognitively normal comparison subject.

Advance Planning

Advance planning status was recorded as part of the standard psychosocial assessment that was conducted at each participant’s baseline visit. Master’s-level social workers administered a semistructured interview which included two items related to advance planning; a) designation of a DPOA, or b) completion of a LW. Comparison subjects and those with minimal cognitive impairment provided this information by self-report. If the social worker determined through clinical assessment that the participant’s capacity to self-report was questionable, these data were obtained from or verified by their informant. Responses to items related to planning status were recorded using a checklist format.

Sociodemographic Factors

Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and education level were systematically collected at baseline using a clinician-administered sociodemographic questionnaire. These variables were included in the current analysis because they have been shown to predict advance care planning in other populations.11-14 Family dementia history was ascertained via clinical interview at the time of the baseline ADRC evaluation. Because knowing someone with cognitive impairment has been found to be positively associated with the conduct of advance planning,12 we included the dichotomized variable, “known history of dementia in a first degree relative,” as a potential correlate in the current study, using the presence of such a family history as a proxy for having witnessed first-hand an individual with progressively impaired decisional capacity.

Diagnostic Groupings

We divided the participants who were diagnosed with a cognitive disorder into two groups on the basis of their level of cognitive impairment. One group consisted of participants with MCI as well as those with early AD, defined as scoring 20 or higher on the Mini-Mental Status Exam 15 and having a consensus diagnosis of probable or possible AD. The second group included participants with moderate to severely advanced AD (i.e., a consensus diagnosis of probable or possible AD and Mini-Mental Status Exam scores of 19 or lower).

Analytic Approach

We first compared baseline characteristics across the diagnostic categories of cognitively normal (or, comparison subject), MCI or early AD, and moderate or severe AD (Table 1). Binary logistic regression analyses were then conducted to identify factors associated with the planning behaviors of DPOA and LW completion. The following sociodemographic factors were tested: age, gender, ethnicity (European American versus African American; the three cases of other minorities were excluded due to insufficient cell sizes; see Table 1), marital status (not married versus married), educational status (high school or less versus the levels of some college and college graduate), and family dementia history (absent versus present). Note that marital status was dichotomized due to small cell sizes in the not married categories; likewise, the high school and less than high school categories of education were combined for the multivariate analyses.

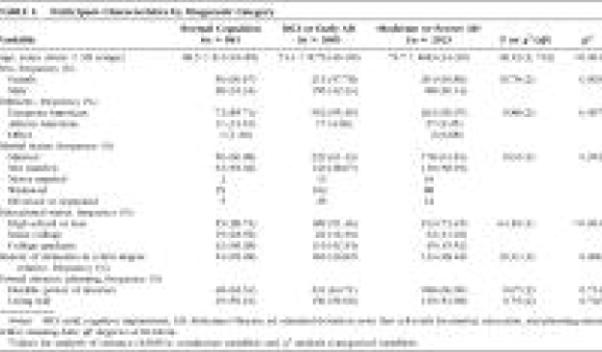

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics by Diagnostic Category

|

DPOA and LW data were missing in 6% and 8% of the cases, respectively. We excluded these cases from the regression analyses. Missing data analysis revealed that rates of missingness did not differ by diagnostic category, age, ethnicity, gender, marital status, educational status, or family history of dementia status.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

A total of 745 individuals were included in the sample (Table 1). Participants ranged in age from 44 to 99 years with a mean age of approximately 74 years; 63% were women and 37% were men. Eleven percent of the participants were cognitively normal comparison subjects, 50% met diagnostic criteria for MCI or early AD, and 39% met criteria for moderate or severe AD. There were significant demographic differences between the three study groups (Table 1). Comparison subjects were younger, less likely to be European American, more highly educated, and more likely to have a first degree relative with dementia than individuals in either of the cognitive impairment groups. Patients with moderate or severe AD were most likely to be female. Despite these differences in group composition, rates of formal advance planning were similar across diagnostic categories with 69% of normal controls, 71% of participants with MCI or early AD and 70% of those with moderate or severe AD reporting engagement in at least one type of planning.

Correlates of Formal Advance Planning

The odds ratios and adjusted 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with the formal advance planning behaviors of DPOA designation and LW completion are presented in Table 2. Consistent with the bivariate analysis reported in Table 1, multivariate analysis revealed no significant differences in the prevalence of advance planning among participants meeting diagnostic criteria for MCI or early AD, as compared with cognitively normal subjects or those with moderate to severe AD. Across all groups, the performance of formal advance planning behaviors was associated with increased age, higher education level, and European American ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Logistic Regression Analyses of Factors Associated With Formal Advance Planning

|

With every year of increased age, the rate of DPOA completion increased by 5.2% (OR = 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.07) and the rate of LW completion increased by 4.3% (OR = 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06). As expected, educational status was also associated with both types of formal advance planning. Of those with a high school level of education or less, 62% reported having a DPOA, compared with 65% of those with 13-15 years of education, and 72% of those with a 4-year college degree ([chi]2 = 6.49, df = 2, p = 0.04). A similar effect was noted for LW completion. Fifty-one percent of those with a high school, or less than high school, level of education reported having a LW, compared with 58% of those with 13-15 years of education, and 65% of those with a 4-year college degree ([chi]2 = 11.03, df = 2, p = 0.004). These differences were significant by logistic regression analysis; participants with a college degree were twice as likely (OR = 2.06; 95% CI, 1.33-3.20) to have a DPOA, and nearly twice as likely (OR = 1.84; 95% CI, 1.23-2.79) to have a LW, than those reporting a high school, or less than high school, level of education (Table 2).

Ethnicity also emerged as a strong correlate of planning status. In our sample, 68% of European American and 36% of African American participants reported having a DPOA ([chi]2 = 20.39, df = 1, p <0.001); 59% of European American and 16% of African American participants reported having a LW ([chi]2 = 33.13, df = 1, p <0.001). With adjustment for age, education, and other potential covariates, our analysis revealed that European American were still five times more likely (OR = 4.75; 95% CI, 2.40-9.38) to have designated a DPOA and six times more likely (OR = 6.47; 95% CI, 2.88-14.54) to have completed a LW than were African American participants.

To better understand the effects of sociodemographic factors on planning behaviors, we conducted a series of interaction analyses. We tested for interactions between sociodemographic variables (regardless of their significance at the main effects level) and our primary variable of interest, diagnostic category. Logistic regression revealed an interaction between age and diagnostic grouping, with the effect of increased age on the likelihood of DPOA designation being most influential within the comparison group ([chi]2 = 11.29, df = 2, p = 0.004). Cognitively, normal comparison subjects under the age of 60 were least likely to have designated a DPOA. Marital status also interacted with diagnostic grouping; unmarried participants in the moderate to severe AD group were four times more likely to have a DPOA than were unmarried comparison subjects (OR = 4.35; 95% CI, 1.26-15.08). Neither education nor ethnicity was found to significantly interact with any of the other variables in the models shown in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

AD poses a particular challenge to advance planning as affected persons can experience a multitude of acute medical and other life events superimposed upon a course of progressive decisional incapacity. Our data indicate that while a majority of older adults with MCI and AD have engaged in formal advance planning by the time of presentation to a subspecialty clinic, a substantial minority have not. We were interested in persons with MCI and early AD because such diagnoses may afford persons at heightened risk for sustained decisional impairment a unique, but time-limited, opportunity to plan for future medical, financial, and other life decisions. Support for the importance of advance planning is found in reports that end of life care and the burden of proxy decision making are strenuous aspects of dementia family caregiving,16,17 particularly under circumstances in which a patient’s wishes are unknown. Yet, we found that levels of formal advance planning among persons with MCI and early AD do not exceed those for healthy older adults, nor do they differ from the planning rates of those with moderate to severe AD. Our findings that young comparison subjects were least likely and unmarried patients with advanced AD were most likely to have a DPOA, may reflect the conduct of legal planning in response to major life events like retirement, divorce, or the death of a spouse. However, the insidious nature of dementia-imposed decisional impairment suggests that there is also a need for clinically triggered advance planning, which may occur in specialty settings like ADRCs or the offices of geriatric psychiatrists and other clinicians who assess those exhibiting the earliest symptoms of cognitive impairment. The potential benefit of recommending advance planning early in the course of cognitive impairment is underscored by earlier work showing that family caregivers of advanced AD patients cite failure to recognize the need for planning before it is “too late,” as the most common reason for lack of planning.18

Overall, 65% of the participants in our sample reported having designated a DPOA and 56% reported having completed a LW. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document the prevalence of advance planning among patients seen in a memory disorders specialty setting. The rates of planning observed in our ADRC cohort are higher than those found in national estimates from the 1990s,19-22 but fall well within the mid-range of recently derived prevalence rates. Prospective studies of community-dwelling older adults and ambulatory internal medicine patients find rates of formal advance planning to range from 43% to 80%, with increased age and higher levels of education being positive associated with the presence of planning.12-14

With regard to the association between ethnicity and advance planning, a number of studies have been conducted in the end-of-life context to explain why advance directives have low completion rates in various non-white racial or ethnic groups. This body of research suggests that lower planning rates among African Americans may be related to lack of knowledge about, and negative attitudes toward, advance planning.23-25 Preliminary evidence from focus groups suggests that African Americans may perceive the utility of advance planning as limited, viewing such directives as unlikely to be followed by health care professionals.26

Indeed, formal advance planning mechanisms have been strongly criticized for their inadequacy under real-time care scenarios.27 However, the United States legal system generally recognizes written documentation of one’s wishes and preferences over informal planning.28,29 Recent studies associate having an advance directive with fewer aggressive treatments and lower rates of hospitalization at life’s end;30,31 these findings call into question previous claims that advance planning does not significantly impact care dynamics,32 suggesting that advance planning may hold value for patients with well-defined preferences for future care.

The current study has a number of limitations. Most participants were European American, with African Americans being the only minority represented. Many of the African American participants in our sample were recruited through targeted minority outreach initiatives, whereas most European Americans were self- or physician-referred. These differences in recruitment pathways may have amplified the finding of a disparity in planning behaviors. The ADRC setting may introduce additional bias. The requirement that the patient have an informant carries the risk of excluding marginalized individuals who may lack access to legal planning or have different motivations for conducting such planning. Individuals who come to specialty clinics might be the most likely to have engaged in planning while first symptomatic, suggesting that our findings may represent a best case scenario. However, the numbers who had made such plans were not overwhelming, and whereas unmarried patient with moderate to severe AD were most likely to have a DPOA, there was no statistically reliable evidence that more severely ill subjects had higher rates of LW completion. Further, only formal planning was assessed here. Future research should investigate the extent to which people are informally planning (e.g., having the necessary conversations).

Despite the limitations noted above, our data suggest that individuals with early evidence of cognitive changes may represent an important target for clinically driven and culturally tailored advance planning interventions. Discussions about such planning should be an integral part of any clinical encounter with a patient with MCI or early AD and his or her family.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 MH19986, P50 AG05133, and P30 MH71944. Preparation of this manuscript was in part supported by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NR08272, 09573), National Institute of Aging (AG15321, AG026010), National Institute of Mental Health (MH071944), National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (MD000207), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL076852, HL076858), and the National Science Foundation (EEEC-0540856).

References

- 1.Kim SYH, Karlawish JHT, Caine ED. Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschman KB, Xie SX, Feudtner C, et al. How does an Alzheimer’s disease patient’s role in medical decision making change over time? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:55–60. doi: 10.1177/0891988704264540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurrera RJ, Moye J, Karel MJ, et al. Cognitive performance predicts treatment decisional abilities in mild to moderate dementia. Neurology. 2006;66:1367–1372. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210527.13661.d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: what do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Neurology Ethics and Humanities Subcommittee Ethical issues in the management of the demented patient. Neurology. 1996;46:1180–1183. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Nurses Association . Position Statement on Nursing Care and Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) Decisions. American Nurses Association; Washington, D.C.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyketsos C, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:561–573. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Klunk W, et al. Research evaluation and diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease over the last two decades: I. Neurology. 2000;55:1854–1862. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Part 1. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: results from a national study. Gerontologist. 2000;40:449–457. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bravo G, Dubois MF, Paquet M. Advance directives for health care and research: prevalence and correlates. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosnick CB, Reynolds SL. Thinking ahead: factors associated with executing advance directives. J Aging Health. 2003;18:409–429. doi: 10.1177/0898264303015002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freer JM, Eubanks M, Parker B, et al. Advance directives: ambulatory patients’ knowledge and perspectives. Am J Med. 2006;119:1088.e9–1088.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prigerson HG, Cherlin E, Chen JH, et al. The Stressful Caregiving Adult Reactions to Experiences of Dying (SCARED) Scale: a measure for assessing caregiver exposure to distress in terminal care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forbes S, Bern-Klug M, Gessert C. End-of-life decision making for nursing home residents with dementia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2000;32:251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH. Why doesn’t a family member of a person with advanced dementia use a substituted judgment when making a decision for that person? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:659–667. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203179.94036.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emanuel LL, Barry MJ, Stoeckle JD. Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103283241305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamble ER, McDonald PJ, Lichstein PR. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of elderly persons regarding living wills. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanson LC, Rodgman E. The use of living wills at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1018–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL. Death and end-of-life planning in one Midwestern community. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:383–390. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mebane EW, Oman RF, Kroonen LT, et al. The influence of physician race, age, and gender on physician attitudes toward advance care directives and preferences for end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:579–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waters CM. End-of-life care directives among African Americans: lessons learned—a need for community-centered discussion and education. J Community Health Nurs. 2000;17:25–37. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1701_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullock K. Promoting advance directives among African Americans: a faith-based model. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:183–195. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient Self-Determination Act in Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. Federal Law. 1990:101–508. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greco P, Schulman K, Lavizzo-Mourey R, et al. The patient self-determination act and the future of advance directives. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:639–643. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-8-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, et al. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degenholtz HB, Rhee YJ, Arnold RM. Brief communication: the relationship between having a living will and dying in place. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:113–117. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-2-200407200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teno JM, Lynn J, Phillips RS, et al. Do formal advance directives affect resuscitation decisions and the use of resources for seriously ill patients? SUPPORT Investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. J Clin Ethics. 1994;5:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]