Abstract

Background

Temporary use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) prior to heart transplantation has been associated with formation of antibodies directed against human leukocyte antigens (HLA), often referred to as sensitization. Identifying specific factors that might predispose patients to form HLA-specific antibodies after LVAD implantation may facilitate the development of strategies to prevent high degree of sensitization. We investigated whether prior sensitization or LVAD type affected the degree of post-implantation sensitization.

Methods

We reviewed the records of consecutive HeartMate (HM) I and HM II LVAD patients. Panel reactive antibody (PRA) was assessed, either with antiglobulin cytotoxicity or flow cytometry, prior to LVAD implantation and biweekly thereafter. Sensitization was defined as PRA >10% and high degree sensitizization was defined as a PRA >90%.

Results

Sixty-four patients underwent implantation with a HM I LVAD and 11 patients with a HM II LVAD as a bridge to transplant. Among the HM I patients, 10 (16%) were sensitized before LVAD implantation (HM I-SENSITIZED), averaging a PRA of 50±35 %, and 54 (84%) were not (HM I-NON-SENSITIZED). Nine of 10 HM I-SENSITIZED patients (90%) became highly sensitized (PRA>90%) compared to only 9/54 HM I-NON-SENSITIZED patients (16.7%) (p<0.001). Despite similar duration of mechanical support, the PRA remained elevated (>90%) in all but 1 of the highly sensitized pts in HM I-SENSITIZED (8/9, 88.9%), compared to only 5/9 (55.6%) of the highly sensitized pts in HM I-NON-SENSITIZED. In the rest of the HM I-SENSITIZED highly sensitized pts PRA declined from a peak value of 93±4% to 55±15% (p= 0.01). Among the HM II patients, 1 (9 %) was sensitized before LVAD implantation (PRA 40%) and 10 (91%) were not sensitized. The sensitized HM II patient did not become highly sensitized but did moderately increase the PRA to 80%. No other HM II patient became sensitized after implantation. Thus, fewer HM II patients became sensitized when compared to the HM I patients [1/11 (9%) vs 29/64 (45%); p=0.04].

Conclusion

Pre-sensitized patients are at higher risk for becoming and remaining highly HLA-allosensitized after LVAD implantation. Furthermore, HeartMate II LVAD appears to cause less sensitization than HeartMate I LVAD.

INTRODUCTION

Temporary left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have been widely used to keep candidates alive who otherwisewould not survive to transplantation (1). Unfortunately, many mechanically supported heart transplant candidates develop serum antibodies directed against human leukocyte antigens (HLA), manifest as elevation of the panel reactive antibody (PRA). This is a also referred to as sensitization (2, 3, 4). Sensitization often mandates a prospective donor-recipient crossmatch which in turn limits the donor pool and increases the waiting time to transplantation. This is especially true in highly sensitized patients. In the past, HLA allosensitization has been associated with adverse post-transplant clinical outcomes, such as higher mortality and increased rates of acute and chronic allograft rejection (5–9). More recent data suggest these adverse clinical outcomes may not be as significant as previously described (10).

While multiple strategies have been used to prevent or decrease allosensitization (11, 12), they have had variable success and it remains unclear which patients are at the highest risk of becoming highly sensitized. Furthermore, it is unclear whether LVAD implantation potentiates the degree of sensitization in patients who are already sensitized, i.e., have a PRA > 0. The purpose of this study was two-fold; first, to determine whether sensitization prior to LVAD implantation might predispose patients to become highly sensitized after implantation; and second, to examine whether the specific LVAD device type affects the occurrence and degree of post-implantation sensitization.

METHODS

Patient population

We reviewed the records of patients with end-stage heart failure who were treated with HeartMate I and II LVAD (Thoratec, Pleasanton, California) implantation as a bridge to transplant. The study was approved by the institutional review board and all patients provided informed consent for collection of data used in this study.

PRA Determination and Sensitization Definitions

The sera were subjected to PRA determination against a panel of donor lymphocytes representing the spectrum of HLA specificities. The PRA assays were performed either by the antiglobulin augmented, complement-dependent lymphocytotoxicity assay or by Luminex flow cytometry. All samples were treated with dithiothreitol to remove immunoglobulin M sensitivity. Panel reactive antibody (PRA) was assessed prior to LVAD implantation and biweekly thereafter.

Sensitization was defined as a PRA >10% and a high degree of sensitization was defined as a PRA >90%. Perioperative transfusion was defined as transfusion in the first 14 days following LVAD implantation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Results of continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were compared with a Pearson χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared with a Student’s t test. Statistical significance was accepted if the null hypothesis was rejected at p less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Sixty-four patients underwent implantation with a HM I LVAD and 11 patients with a HM II LVAD, as a bridge to transplant. Ten of 64 HeartMate I patients were sensitized before LVAD implantation (HM I-SENSITIZED, average PRA 50±35%), 54 of 64 HeartMate I patients were not sensitized (HM I-NON-SENSITIZED). The HM I-SENSITIZED group was composed of a higher percentage of females than the HM I-NON-SENSITIZED group. Other baseline characteristics including age, perioperative transfusion rates of cellular blood products and duration of support were not significantly different between the two HM I groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of HeartMate I patients

| SENSITIZED (n=10) | NON-SENSITIZED (n=54) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.2 ± 16.5 | 50.2 ± 11.1 | 0.06 |

| Female Sex (percent) | 40% | 9% | 0.03 |

| PRA at baseline (percent) | 49.8 ±34.6 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.001 |

| Total PRBCs (units) | 8.3 ± 9.3 | 12.7 ± 16.8 | 0.42 |

| Total Platelets (units) | 3.7 ± 5.3 | 3.5 ± 3.7 | 0.86 |

| Duration of Support (days) | 219.6 ± 160.7 | 176.6 ± 171 | 0.46 |

SENSITIZED: PRA > 10%; PRA: panel reactive antibody; PRBC: packed red blood cells

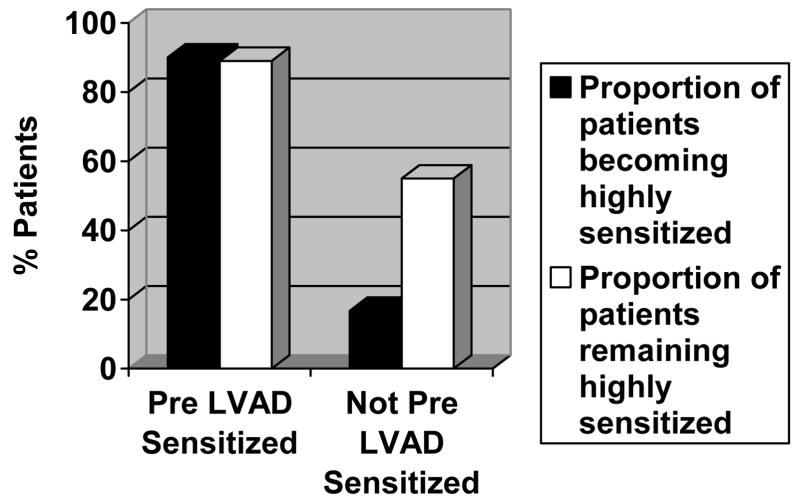

Nine of 10 HM I-SENSITIZED patients (90%) became highly sensitized (PRA>90%) compared to only 9 of 54 patients (17%) in the HM I-NON-SENSITIZED group (p<0.001; Figure 1) during treatment with mechanical circulatory support. Gender, transfusion rates and duration of support were similar between the highly sensitized patients of both HM I groups (Table 2). There was a trend for the PRA to remain highly elevated (>90%) in the HM I-SENSITIZED group (8 of 9 patients, 88.9%), compared to only 5 of 9 (55.6%) of the highly sensitized patients in the HM I-NON-SENSITIZED group (Figure 1). Furthermore, in the highly sensitized patients of the HM I-NON-SENSITIZED group whose PRA did not remain >90% a significant PRA decline from a peak value of 93±4% to 55±17% was observed (p= 0.02).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with high-degree sensitization (panel reactive antibody > 90%) after HeartMate I implantation and proportion of the highly sensitized patients that remained with high-degree sensitization throughout the follow up period

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Heartmate I Patients with high-degree sensitization post LVAD implant

| HMI patients with pre- implant sensitization and high-degree sensitization post-implant (n=9) | HMI patients without pre-implant sensitization and high-degree sensitization post-implant (n=9) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 44±17 | 46±15 | 0.77 |

| Female | 3 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Perioperative Transfusions (units) | 7.0±8.7 | 6.6±9.1 | 0.92 |

| Total PRBCs (units) | 1.0±2.6 | 0.2±0.7 | 0.41 |

| Total Platelets (units) | 0.4±1.3 | 0 | 0.35 |

| Duration of Support (days) | 234±163 | 393±180 | 0.07 |

High-degree sensitization: Panel reactive antibody > 90%; Sensitized: Panel reactive antibody > 10%; PRBC: packed red blood cells

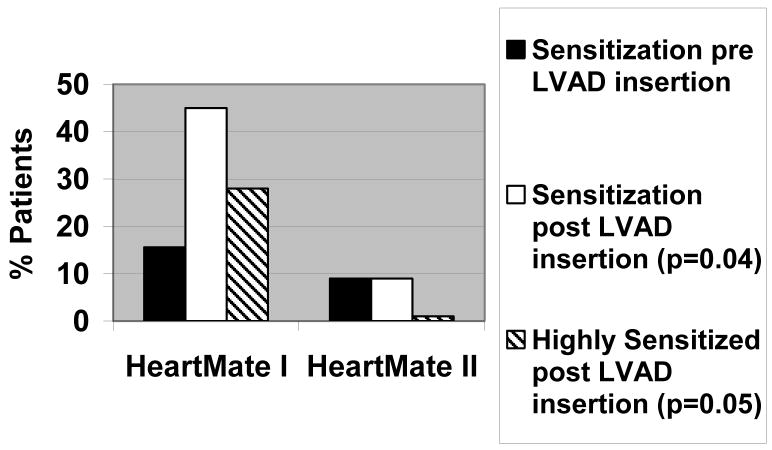

The HM II patients had similar baseline characteristics compared to the HM1 patients (Table 3). Despite similar duration of support, only 1/11 HM II patient became sensitized compared to 29/64 HM I patients (9% vs 45%; p=0.04, Figure 2). Interestingly, the HM II patient that developed sensitization was already sensitized prior to LVAD insertion and further increased his PRA level (from 40% to 80%). No HM II patients became highly sensitized compared to 18 HM I patients (0% vs 28%; p=0.05, Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Baseline characteristics of HeartMate I and HeartMate II patients

| HM1 Group (n=64) | HM2 Group (n=11) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49±12 | 52±8 | Ns |

| Gender (M/F) | 55/9 | 7/4 | Ns |

| Etiology of Heart Failure (Ischemic/Non ischemic) | 68%/32% | 63%/37% | Ns |

| Packed red blood cells (units) | 12.0±15.9 | 11.5±12.9 | Ns |

| Platelets (units) | 3.5±3.9 | 3.5±3.7 | Ns |

| Duration of Support | 183±169 | 225±330 | Ns |

| Pre LVAD sensitization (%) | 15.6 | 9.0 | Ns |

LVAD: left ventricular assist device

Figure 2.

Sensitization outcomes in HeartMate I and HeartMate II LVADs

DISCUSSION

The advent of temporary mechanical circulatory support for the failing left ventricle has been life-saving for selected patients awaiting heart transplantation (1, 13, 14). Despite the success of this LVAD-bridging to transplant, many mechanically supported heart transplant candidates develop circulating anti-HLA antibodies with potential donor reactivity, manifest as an elevation of the PRA (2, 3, 4). Having an increased PRA has been shown to increase transplant waiting times (15) and leads to adverse clinical outcomes even after a crossmatch compatible transplant (7, 8).

Our data identify an increased PRA prior to LVAD implantation as a risk factor for developing a high-degree (PRA>90%) HLA allosensitization that tends to persist in time.. The patients who were sensitized prior to LVAD implantation included a higher proportion of women. It has been described that women are more likely to have an increased PRA level prior to LVAD implantation (16). However, Massad et al documented that post LVAD implantation increases in PRA levels do not correlate with gender (16). Our data also suggest that while female gender is a risk factor for elevated PRA, gender does not seem to be associated with increased risk of becoming or remaining highly sensitized following LVAD implantation.

Perioperative transfusions could represent a plausible confounding factor. It has been suggested that perioperative transfusion of cellular blood products increase sensitization after LVAD implantation (4, 16, 17). However, we have previously shown that avoidance of perioperative cellular transfusions did not decrease the incidence or degree of HLA sensitization (18, 19). Conversely, transfusions may be associated with less alloimmunization and may mitigate the sensitization seen in bridge to transplant LVAD recipients (19). Whatever the effect of transfusions on sensitization might be, there were no significant differences between the number of cellular transfusions administered to any group or subgroup of patients compared in our analysis.

In HM I patients, the duration of support in both the pre-LVAD sensitized patients and in those who were not sensitized prior to implantation was similar. The duration of support in the highly sensitized patients of the non pre-LVAD sensitized subgroup tended to be longer than in their counterparts in the pre-LVAD sensitized subgroup (Table 2). However, it has been shown that longer duration of support does not provide a continuous increased risk for allosensitization (16). Pagani et al, demonstrated that the median duration of support time to peak PRA was less than forty days (20). We have shown that sensitization is a phenomenon that typically occurs during the first 3 months of mechanical support (11, 19). Thus, it seems that post LVAD sensitization is a phenomenon that would occur relatively early after LVAD implantation and further prolongation of LVAD support would not add to the likelihood of becoming sensitized. Therefore, given the fact that the duration of support for both sensitized and non sensitized pre-HM1 LVAD subgroups was well beyond this time limit where sensitization would be expected, comparing the sensitization rate and degree between these groups seems appropriate.

However, the same rationale might not apply when comparing the rates and degree of de-sensitization. The fact that the highly-sensitized patients of the pre-HM I non-sensitized subgroup had longer duration of support raises the possibility that they decreased their HLA antibodies while their highly sensitized counterparts in the sensitized pre-HM I subgroup did not because the latter were given less time to do so. However, Kumpati and colleagues showed that the temporal pattern of sensitization consisted of a rapid increase followed by a rapid progressive decrease, and their data showed a decrease in sensitization occurring within 4 months of becoming sensitized (21). Our own data show a similar trend. Therefore, given the average duration of support in these two groups of patients we would not attribute the differences in decreasing the degree of sensitization to the observed trend for different duration of LVAD therapy.

The effects of the LVAD type on the host immune system could have potentially important clinical consequences when considering LVAD implantation as a bridge to transplant in patients at high risk for development of sensitization. Host interactions with device biomaterials, specifically the textured chamber surface found in the HM I LVAD, have been proposed as one of the mechanisms responsible for an increased immunologic and inflammatory response seen after LVAD support (3). The pseudointima formed on the textured surface of the HM I device contains an abundance of T cells, macrophages, and monocytes and reflects the constant interaction of blood with the device (3). Specifically, aberrant T-cell activation on the LVAD surface, defective T-cell proliferation and polyclonal B-cell hyperreactivity with CD40 ligand interactions have been observed post LVAD implantation (3, 22, 23).

Newer generation axial-flow devices such as HM II have been hypothesized to result in lower immunologic and inflammatory response than HM 1. Plausible explanations are the lower overall textured surface area (which is limited to the inflow cannula in HM II device) and the absence of biologic valves. Yet, this issue has not been adequately investigated; one study of 14 patients receiving axial-flow DeBakey device reported that no patients became sensitized during mechanical support (24). George et al (25) compared sensitization rates between HM I devices (n=36) and axial flow devices (HM II or DeBakey, n= 24) and and found that HM I was associated with significantly increased incidence of allosensitization (28% vs 8%) which is consistent with the results of our study. These findings are encouraging given the current trend towards increased use of continuous flow assist devices.

The limitations of this study include those related to a retrospectively performed analysis. Data were obtained by means of chart and electronic database review, which has inherent limitations, such as access and accuracy of the data. The small number of HM II patients included in our study and the uneven number of patients in the two groups are additional limitations of our study.

In conclusion, presensitized patients seem to be at higher risk for becoming and remaining highly HLA allosensitized after LVAD implantation. Furthermore, HM II LVAD appears to cause less sensitization than HM I LVAD. Therefore, when considering LVAD implantation as a bridge to transplant in patients at increased risk for development of sensitization, newer-generation continuous-flow devices should be given preference. Further research is warranted to validate these results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Frazier OH, Rose EA, Oz MC, et al. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the HeartMate vented electric left ventricular assist system in patients awaiting heart transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:1189 –95. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.118274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John R, Lietz K, Schuster M, et al. Immunologic sensitization in recipients of left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:578–91. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itescu S, John R. Interactions between the recipient immune system and the left ventricular assist device surface: immunological and clinical implications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:S58–65. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenna DH, Jr, Eastlund T, Segall M, Noreen HJ, Park S. HLA alloimmunization in patients requiring ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:1218–24. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavee J, Kormos RL, Duqesnoy RJ, et al. Influence of panel reactive antibody and lymphocytotoxic crossmatch on survival after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1991;10:921–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose EA, Pepino P, Barr ML, et al. Relation of HLA antibodies and graft atherosclerosis in human cardiac allograft recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11(3 Pt 2):S120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobashigawa JA, Sabad A, Drinkwater DGA, et al. Pretransplant panel reactive-antibody screens. Are they truly a marker for poor outcome after cardiac transplantation? Circulation. 1996;94:II294–II297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Mattos AM, Head MA, Everett J, et al. HLA-DR mismatching correlates with early cardiac allograft rejection, incidence, and graft survival when high-confidence-level serological DR typing is used. Transplantation. 1994;57:626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerbe TR, Arena VC, Kormos RL, Griffith BP, Hardesty RL, Duquesnoy RJ. Histocompatibility and other risk factors for histologic rejection of human cardiac allografts during the first three months following transplantation. Transplantation. 1991;52:485–90. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199109000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce DL, Southard RE, Torre-Amione G, et al. Impact of left ventricular assist device (LVAD)-mediated humoral sensitization on post-transplant outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2054–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drakos SG, Kfoury AG, Long JW, et al. Low-Dose Prophylactic Intravenous Immunoglobulin Does Not Prevent HLA Sensitization in Left Ventricular Assist Device Recipients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:889–94. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehra MR, Uber PA, Uber WE, Scott RL, Park MH. Allosensitization in heart transplantation: implications and management strategies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2003;18:153– 8. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drakos SG, Kfoury AG, Long JW, et al. Effect of mechanical circulatory support on outcomes after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng MC, Edwards LB, Hertz MI, et al. Mechanical circulatory support device database of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: second annual report—2004. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:1027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsau PH, Arabia FA, Toporoff B, et al. Positive panel reactive antibody titers in patients bridged to transplantation with a mechanical assist device: risk factors and treatment. ASAIO J. 1998;44:M634–7. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199809000-00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massad MG, Cook DJ, Schmitt SK, et al. Factors Influencing HLA sensitization in implantable LVAD recipients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;64:1120–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moazami N, Itescu S, Williams MR, Argenziano M, Weinberg A, Oz MC. Platelet transfusions are associated with the development of anti-major histocompatibility complex class I antibodies in patients with left ventricular assist support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:876–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stringham JC, Bull DA, Fuller TC, et al. Avoidance of cellular blood product transfusions in LVAD recipients does not prevent HLA allosensitization. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:160 –5. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(98)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drakos SG, Stringham JC, Long JW, et al. Prevalence and risks of allosensitization in HeartMate left ventricular assist device recipients: the impact of leukofiltered cellular blood product transfusions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1612–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagani FD, Dyke B, Wright S, et al. Development of Anti-Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I or II Antibodies Following Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: Effects on Subsequent Allograft Rejection and Survival. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:646–53. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumpati GS, Cook DJ, Blackstone EH, et al. HLA sensitization in ventricular assist device recipients: Does type of device make a difference? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1800–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster M, Kocher AA, John R, Kukuy E, Edwards NM, Oz MC, et al. Allosensitization following left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation is dependent on CD4-CD40 ligand interactions. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:211–2. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuster M, Kocher A, John R, et al. B-cell activation and allosensitization after left ventricular assist device implantation is due to T-cell activation and CD40 ligand expression. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:211–20. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinda JM, Bricourt MO, Amrein C, et al. Human leukocyte antigen sensitization in ventricular assist device recipients: a lesser risk with the DeBakey axial pump. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:945–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George I, Colley P, Russo MJ, Martens TP, Burke E, Oz MC, Deng MC, Mancini DM, Naka Y. Association of device surface and biomaterials with immunologic sensitization after mechanical support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:1372–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]