Abstract

Objective

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) acts in cytoprotection against acute lung injury. The polymorphic (GT)n repeat in the HO-1 gene (HMOX1) promoter regulates HMOX1 expression. We investigated the associations of HMOX1 polymorphisms with ARDS risk and plasma HO-1 levels.

Design

Unmatched, nested case-control study.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Patients

Consecutive patients with ARDS risk factors upon ICU admission were prospectively enrolled. Cases were 437 Caucasians who developed ARDS and controls were 1014 Caucasians who did not.

Measurements and results

We genotyped the (GT)n polymorphism and three tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) in 1451 patients, and measured the plasma HO-1 levels in 106 ARDS patients. We clustered the (GT)n repeats into: S-allele (< 24 repeats), M-allele (24–30 repeats) and L-allele (≥ 31 repeats). We found that longer (GT)n repeats were associated with reduced ARDS risk (Ptrend = 0.004 for both alleles and genotypes), but no individual tSNP was associated with ARDS risk. HMOX1 haplotypes were significantly associated with ARDS risk (global test, P = 0.016), and the haplotype S-TAG was associated with increased ARDS risk (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.15–2.68; P = 0.010). Intermediate-phenotype analysis showed longer (GT)n repeats were associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels (Ptrend = 0.019 for alleles and 0.027 for genotypes).

Conclusions

Longer (GT)n repeats in the HMOX1 promoter are associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels and reduced ARDS risk. The common haplotype S-TAG is associated with increased ARDS risk. Our results suggest that HMOX1 variation may modulate ARDS risk through the promoter microsatellite polymorphism.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, genetic susceptibility, haplotypes, heme oxygenase-1, microsatellite polymorphism, molecular epidemiology

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a common and devastating disease in the intensive care units (ICU) worldwide, with a high mortality rate of 35 to 40% [1]. Recently, there is increasing evidence that heritable susceptibility may explain at least part of the risk of developing ARDS after pulmonary or extrapulmonary insults.

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is an inducible isoform of HO, which catalyzes the degradation of heme, a pro-oxidant, into carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and iron [2]. Biliverdin is subsequently converted to bilirubin, and iron is sequestered by ferritin. These metabolites of heme catabolism have anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects, and therefore, HO-1 has emerged as an important cytoprotective enzyme in the human body [3, 4].

Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance is important in the complex pathogenesis of ARDS [5, 6]. Expression of the antioxidant enzyme HO-1 is upregulated in animal models and human lungs of ARDS [7, 8]. Animal studies showed that HO-1 plays a protective role against acute lung injury induced by hyperoxia, ischemia-reperfusion, and endotoxin [3, 9]. Overexpression of HO-1 by gene transfer protects rat lungs against hyperoxia-induced lung injury [10]. Induction f HO-1 by hemoglobin protects rat lungs against hyperoxia- [11] and endotoxin-induced lung injury [12]. In a nebulized endotoxin-induced lung injury model, HO-1-deficient mice develop severe lung dysfunction with marked reduction in surfactant protein B levels [13]. In addition, the HO-1-deficient mice exhibit lethal ischemia-reperfusion lung injury but could be rescued from death by inhaled carbon monoxide [14]. To date, evidence has accumulated for the protective effects and therapeutic potential of HO-1, as well as the downstream metabolites, in acute lung injury [15].

The HO-1 gene (HMOX1) is located on chromosome 22q13.1. A polymorphic (GT)n repeat in the HMOX1 promoter regulates the promoter activity and gene expression [16–19]. Studies showed that the longer (GT)n repeats are associated with increased susceptibility to pulmonary diseases such as smoking-induced emphysema [19], pneumonia [20], and asthma [21]. This microsatellite polymorphism has also been associated with a variety of diseases, including coronary artery disease, renal transplantation [3], idiopathic recurrent miscarriage [22], cerebral malaria [23], and rheumatic arthritis [18].

In this study, we hypothesized that HMOX1 variation may influence the susceptibility to ARDS. We genotyped the (GT)n polymorphism and the tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) of HMOX1, and used an unmatched, case-control design to analyze the association of HMOX1 polymorphisms with ARDS development. We also measured the plasma HO-1 levels in a subset of ARDS patients to assess the functional significance of HMOX1 polymorphisms.

Patients and methods

Study population

Study patients were recruited in the ICUs at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, from September 1999 to November 2006. Definitions and details of the study design have been described previously [24]. Briefly, all consecutive admissions to the ICUs were screened. Patients with clinical risk factors for ARDS were eligible for inclusion (see electronic supplementary material, ESM1, for details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria). Baseline characteristics and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III scores were recorded on ICU admission. The enrolled patients were screened daily for ARDS development and those who fulfilled the American-European Consensus Committee (AECC) criteria for ARDS [25] were considered as ARDS cases, whereas at-risk patients who did not develop ARDS during ICU stay were considered as controls. We restricted our analysis to non-Hispanic Caucasians (91.8% in our study population). The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Harvard School of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or surrogates.

Tagging SNPs selection

We selected the tSNPs across the entire HMOX1 gene, including 2 kbp on each side. We used the multimarker tagging algorithm with criteria of minor allele frequency ≥ 0.1 and r2 > 0.8, based on the HapMap data (release 23a) of the CEU population (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe). Because rs2071746 (−413A>T) has been related to the promoter function, this SNP was forced in as a tSNP during the tagging process. As a result, we identified a set of 3 tSNPs that efficiently tagged all known common HMOX1 variants.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Puregene DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or by the AutoPure LS robotic workstation using the Autopure reagents (Qiagen, Valencia, California). The (GT)n polymorphism was genotyped by a PCR method in combination with fluorescence technology as previously described [19]. Briefly, the gene promoter containing the (GT)n repeats was amplified with the labeled forward primer 5’-AGAGCCTGCAGCTTCTCAGA-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-ACAAAGTCTGGCCATAGGAC-3’. The sizes of the PCR products were then determined by Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA analyzer and the GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The tSNPs were genotyped by the TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems). The primers and probes were ordered from Applied Biosystems. The fluorescence of PCR products was detected by the ABI Prism® 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Genotyping was performed by laboratory personnel blinded to case-control status. A random 10% samples were included as duplicates for quality-control. The overall genotyping success rate was > 98% and the concordance rate for duplicate samples was > 99%. Samples not yielding the genotypes of all polymorphisms were excluded from analysis.

Classification of (GT)n repeats

The standard classification of (GT)n repeats remain inconclusive. We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the best cutoffs. The results showed that grouping the alleles into short (S)-allele (< 24 repeats), middle (M)-allele (24–30 repeats), and long (L)-allele (≥ 31 repeats) is the best-fit model (ESM2). We also did a thorough literature review to find the most commonly used grouping criteria. These criteria were S-allele (< 25 repeats) and L-allele (≥ 25 repeats) for two allele groups; and S-allele (< 27 repeats), M-allele (27–32 repeats), and L-allele (≥ 33 repeats) for three allele groups (ESM3).

Plasma HO-1 measurement

Plasma HO-1 levels were determined in 106 ARDS patients with available plasma samples collected during the first 48 hours after ARDS diagnosis. We used the Human HO-1 ELISA Kit (Assay Designs Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) and followed the manufacturer’s assay procedure. This ELISA kit has been quantified for measurement of human blood HO-1 in previous studies [26–28]. All the samples were tested in duplicate.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics between cases and controls were evaluated by χ2 test for categorical variables and by unpaired t-test for continuous variables. We used SAS/Genetics to calculate the allele frequencies, test the deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and analyze the pairwise D’ and r2 values for linkage disequilibrium (LD). We also used SAS/Genetics to generate the maximum likelihood estimates of haplotype frequencies, using the expectation-maximization algorithm. These estimates were then used to assign the probability that each individual possessed a particular haplotype pair.

The differences of allele, genotype and haplotype frequencies between cases and controls were compared by χ2 test. The associations between HMOX1 polymorphisms and ARDS risk were analyzed in logistic regression models, adjusting for age, gender, severity score (modified APACHE III scores, which removed age and PaO2/FiO2 components to avoid colinearity), risk factors for ARDS (as inclusion criteria in this study), and other potential risks for ARDS based on univariate analysis. The genotype associations were analyzed in both codominant and additive models. Haplotypes with frequency > 5% were considered as common haplotypes and rare haplotypes were pooled as a group. We used all other haplotypes as the reference to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) associated with a particular haplotype pair.

We used linear regression models to analyze the associations of clinical variables, genotypes and haplotypes with plasma HO-1, and to calculate the P values or P values for trend (Ptrend). Prior to statistical analysis, plasma HO-1 was Box-Cox transformed to comply with normality. All data were analyzed by SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For significant associations, false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted P values were calculated to correct for multiple testing.

Results

Study population

During the study period, 2626 patients were eligible for enrollment. Nine hundred patients without consents and 96 patients with previous history of ARDS or previous enrollment as controls were not included. As a result, a total of 1630 patients were enrolled into the prospective cohort. Among these participants, 134 non-Caucasians, seven without complete clinical data and 38 without complete genotyping data were excluded sequentially, leaving 1451 patients for analysis. Cases were 437 (30.1%) patients who developed ARDS, and controls were 1014 (69.9%) patients who did not develop ARDS. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Cases, patients developed ARDS (n = 437) | Controls, patients did not develop ARDS (n = 1014) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-yr, mean ± SD | 60 ± 18 | 63 ± 17 | 0.002 |

| Male, n (%) | 264 (60.4%) | 614 (60.6%) | 0.960 |

| APACHE III score, mean ± SD | 77 ± 24 | 67 ± 23 | < 0.001 |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Sepsis (without shock) | 113 (25.9%) | 376 (37.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock | 261 (59.7%) | 442 (43.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 296 (67.7%) | 435 (42.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Aspiration | 43 (9.8%) | 86 (8.5%) | 0.404 |

| Multiple transfusion | 45 (10.3%) | 116 (11.4%) | 0.525 |

| Trauma | 32 (7.3%) | 78 (7.7%) | 0.807 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Post-operative | 28 (6.4%) | 70 (6.9%) | 0.730 |

| Diabetes | 78 (17.9%) | 274 (27.0%) | < 0.001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 27 (6.2%) | 50 (4.9%) | 0.331 |

| Liver cirrhosis/failure | 30 (6.9%) | 38 (3.8%) | 0.010 |

| Metastatic cancer | 13 (3.0%) | 49 (4.8%) | 0.109 |

| History of steroid use | 46 (10.5%) | 91 (9.0%) | 0.354 |

| History of alcohol abuse | 62 (14.2%) | 101 (10.0%) | 0.019 |

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome; APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

Association of HMOX1 (GT)n polymorphism with ARDS

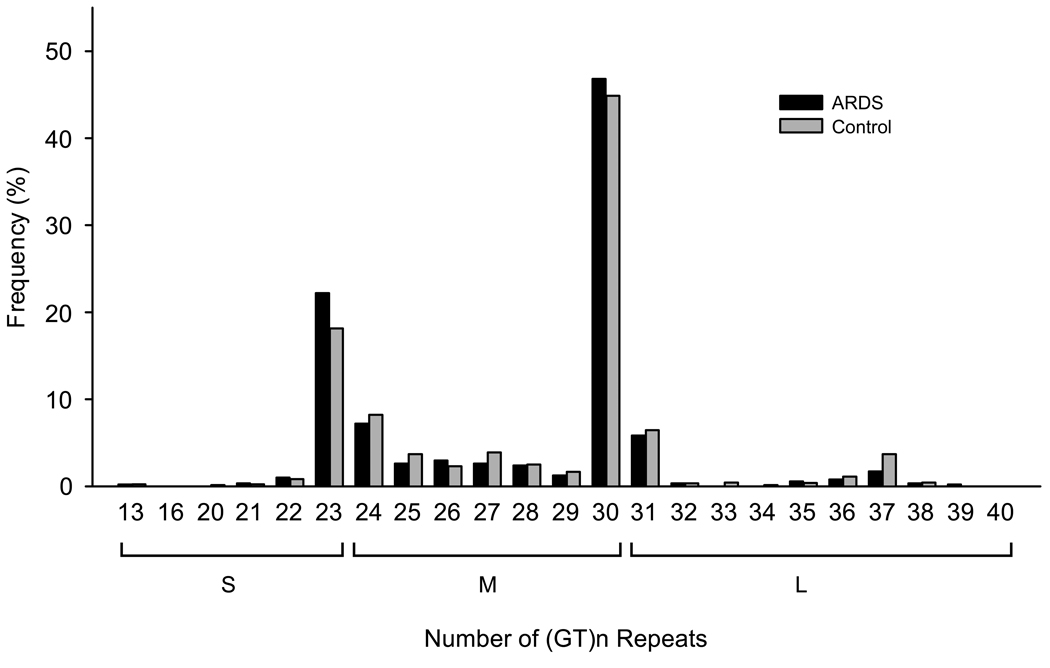

The numbers of (GT)n repeats showed a bimodal distribution of 13 to 40, with two peaks at 23 and 30 repeats (Fig. 1). There was a trend that longer (GT)n repeats were associated with reduced risk of ARDS (Ptrend = 0.026). Based on the results of sensitivity analysis, we divided the (GT)n repeats into: S-allele (< 24 repeats), M-allele (24–30 repeats) and L-allele (≥ 31 repeats), which resulted in six genotypes: SS, SM, MM, SL, ML, and LL.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of (GT)n repeats in patients with ARDS (black bar, n = 437) and controls (gray bar, n = 1014). The numbers of (GT)n repeats ranged from 13 to 40 and showed a bimodal distribution, with one peak located at 23 repeats and the other located at 30 repeats. The overall frequency distribution s of (GT)n repeats were not significantly different between ARDS and controls (χ2 test, P = 0.085). However, there was a trend that longer (GT)n repeats were associated with reduced risk of ARDS (Ptrend = 0.026)

The allele and genotype frequencies of the (GT)n polymorphism are shown in Table 2. The genotype distribution among controls was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.732). We found significant differences of allele and genotype frequencies between ARDS and controls (P = 0.006 and P = 0.033, respectively). In multivariate analysis, longer (GT)n repeats were associated with lower risk of developing ARDS in a gene-dose dependent relationship (Ptrend = 0.004 for both allele and genotype analyses). Individual genotypes of SM, MM, SL, and ML were also significantly associated with reduced ARDS risk (P = 0.009, 0.004, 0.013, and 0.0004, respectively), compared with the genotype SS. Genotype LL, however, did not reach statistical significance due to relatively small sample size.

Table 2.

Associations between HMOX1 (GT)n polymorphism and acute respiratory distress syndrome risk

| Cases | Controls | Incidence | Crude | Adjustedb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 437) | (n = 1014) | of ARDS | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Ptrend | |

| Allelea | 0.006* | 0.004* | |||||||

| S-allele, < 24 repeats | 210 | 398 | 34.1% | 1..00 | 1.00 | ||||

| M-allele, 24–30 repeats | 576 | 1363 | 29.4% | 0.80 (0.66–0.98) | 0.027 | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 0.045 | ||

| L-allele, ≥ 31 repeats | 88 | 267 | 24.6% | 0.63 (0.47–0.85) | 0.002 | 0.66 (0.47–0.88) | 0.004 | ||

| Genotype | 0.033 | 0.004* | |||||||

| SS | 28 | 36 | 43.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| SM | 130 | 269 | 32.6% | 0.62 (0.36–1.06) | 0.082 | 0.46 (0.26–0.83) | 0.009 | ||

| MM | 194 | 465 | 29.9% | 0.55 (0.33–0.92) | 0.023 | 0.44 (0.25–0.78) | 0.004 | ||

| SL | 24 | 57 | 29.6% | 0.54 (0.27–1.08) | 0.080 | 0.39 (0.19–0.82) | 0.013 | ||

| ML | 58 | 182 | 24.2% | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) | 0.002 | 0.33 (0.18–0.61) | 0.0004 | ||

| LL | 3 | 14 | 17.7% | 0.28 (0.07–1.05) | 0.060 | 0.34 (0.08–1.38) | 0.131 | ||

HMXO1 heme oxygenase-1 gene; ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI confidence interval; OR odds ratio: S short; M middle; L long

In allele analysis, n = 858 for ARDS and 2024 for controls

Adjusted for age, gender, APACHE III score, all risk factors for ARDS (listed in table 1), diabetes, liver cirrhosis/failure and alcohol abuse. APACHE III score was revised to remove age and PaO2/FiO2 to avoid colinearity

FDR adjusted P value < 0.05

Then we reclassified the (GT)n repeats according to other common grouping criteria. In the two-allele-group model, the genotype LL remained significantly associated with reduced ARDS risk, compared with genotype SS (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.40–0.98; P = 0.043). In the three-allele-group model, the L-allele was associated with reduced ARDS risk, compared with S-allele (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41–0.96; P = 0.032); and the genotypes with L-allele (SL+ML+LL) were also associated with a reduced ARDS risk, compared with the genotypes without L-allele (SS+SM+MM) (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.42–0.98; P = 0.040) (ESM4).

Association of HMOX1 tSNPs with ARDS

The alleles, locations, chromosome positions, minor allele frequencies, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and pairwise LD of the three tSNPs (rs2071746, rs2071748 and rs5755720) are summarized in ESM5. All tSNPs conformed to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and were in high LD with each other (D’ ≥ 0.982). Only one LD block in HMOX1 gene was found (ESM6). Further LD analysis showed that minor alleles of all three tSNPs were in LD with the S-allele of (GT)n polymorphism (ESM7).

The minor allele and genotype frequencies were not different between ARDS and controls for all tSNPs (Table 3). None of the individual tSNPs showed a significant association with ARDS risk.

Table 3.

Association between HMOX1 tSNPs and acute respiratory distress syndrome risk

| Cases | Controls | Incidence of | Crude | Adjusteda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tSNPs | (n = 437) | (n = 1014) | ARDS | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Ptrendb |

| Alleles, minor allele (MAF) | |||||||||

| rs2071746, T (42.6%) | 360 | 867 | 29.3% | 0.663 | 0.97 (0.82–1.13) | 0.663 | 0.96 (0.81–1.14) | 0.649 | |

| rs2071748, A (38.0%) | 333 | 759 | 30.5% | 0.507 | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 0.506 | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.745 | |

| rs5755720, G (30.6%) | 278 | 604 | 31.5% | 0.173 | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 0.173 | 1.08 (0.90–1.29) | 0.437 | |

| Genotypes | |||||||||

| rs2071746 | 0.882 | 0.688 | |||||||

| AA | 148 | 330 | 31.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| AT | 210 | 499 | 29.6% | 0.94 (0.73–1.21) | 0.621 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.433 | ||

| TT | 79 | 185 | 29.9% | 0.95 (0.69–1.32) | 0.769 | 0.96 (0.67–1.36) | 0.807 | ||

| rs2071748 | 0.524 | 0.686 | |||||||

| GG | 164 | 388 | 29.7% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| AG | 205 | 491 | 29.5% | 0.99 (0.77–1.26) | 0.922 | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) | 0.420 | ||

| AA | 68 | 135 | 33.5% | 1.19 (0.85–1.68) | 0.318 | 1.18 (0.82–1.71) | 0.382 | ||

| rs5755720 | 0.222 | 0.337 | |||||||

| AA | 200 | 494 | 28.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| AG | 189 | 436 | 30.2% | 1.07 (0.85–1.36) | 0.572 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | 0.911 | ||

| GG | 48 | 84 | 36.4% | 0.101 | 1.41 (0.96–2.09) | 0.084 | 1.36 (0.89–2.06) | 0.153 | |

HMXO1 heme oxygenase-1 gene; ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome; tSNP tagging single nucleotide polymorphism; MAF minor allele frequency; CI confidence interval; OR odds ratio

Adjusted for age, gender, APACHE III score, all risk factors for ARDS (listed in table 1), diabetes, liver cirrhosis/failure and alcohol abuse. APACHE III score was revised to remove age and PaO2/FiO2 to avoid colinearity

Regression analysis based on the additive model, indicating the effects of numbers of copies of the minor alleles on ARDS risk

Association of HMOX1 haplotypes with ARDS

Based on the (GT)n polymorphism and tSNPs, 16 haplotypes were found. Five of them were common haplotypes with frequencies > 5%. The haplotypes were expressed in the order of (GT)n polymorphism, rs2071746, rs2071748 and rs5755720, and their frequencies in ARDS patients and controls are shown in Table 4. The estimated frequency of haplotype S-TAG, which carried the short (GT)n repeats and minor alleles of all tSNPs, in ARDS patients was significantly higher than that in controls (22.5% vs. 18.0%, P = 0.005). The global test showed a significant association between HMOX1 haplotypes and ARDS risk in both univariate and multivariate analyses (likelihood ratio test, P = 0.005 and 0.016, respectively). In haplotype-specific analysis, haplotype S-TAG was significantly associated with increased risk of developing ARDS (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.15–2.86; P = 0.010).

Table 4.

Associations between HMOX1 haplotypes and acute respiratory distress syndrome risk

| Estimated Frequency (%) | Crude | Adjustedc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotypesa | Cases (n = 437) | Controls (n = 1014) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Global testb | χ2 = 16.91 | 0.005 | χ2 = 13.98 | 0.016 | |||

| M-AGA | 51.2 | 49.3 | 0.343 | 1.16 (0.84–1.60) | 0.369 | 1.18 (0.83–1.66) | 0.360 |

| S-TAG | 22.5 | 18.0 | 0.005* | 1.76 (1.19–2.62) | 0.005* | 1.75 (1.15–2.68) | 0.010* |

| M-TAG | 9.8 | 11.4 | 0.226 | 0.71 (0.42–1.20) | 0.202 | 0.60 (0.37–1.06) | 0.077 |

| L-AGA | 6.3 | 7.2 | 0.421 | 0.78 (0.41–1.50) | 0.457 | 0.74 (0.37–1.50) | 0.408 |

| M-TAA | 4.3 | 6.0 | 0.057 | 0.51 (0.24–1.09) | 0.084 | 0.59 (0.26–1.33) | 0.202 |

HMXO1 heme oxygenase-1 gene; OR odds ratio; CI confidence interval: S short; M middle; L long

The polymorphisms in the haplotype are arranged in the order of (GT)n polymorphism, rs2071746, rs2071748 and rs5755720

Likelihood ratio test, with 5 degrees of freedom

Adjusted for age, gender, APACHE III score, all risk factors for ARDS (listed in table 1), diabetes, liver cirrhosis/failure and alcohol abuse. APACHE III score was revised to remove age and PaO2/FiO2 to avoid colinearity

FDR adjusted P value < 0.05

Correlations of clinical variables and HMOX1 polymorphisms with plasma HO-1 levels in ARDS patients

There were no significant differences of baseline characteristics, ARDS outcomes, and genotype distributions between ARDS patients with or without plasma HO-1 measured, except for APACHE III scores and history of diabetes (ESM8 and ESM9). None of the demographic or clinical factors was independently associated with plasma HO-1 levels during acute phase of ARDS (ESM10).

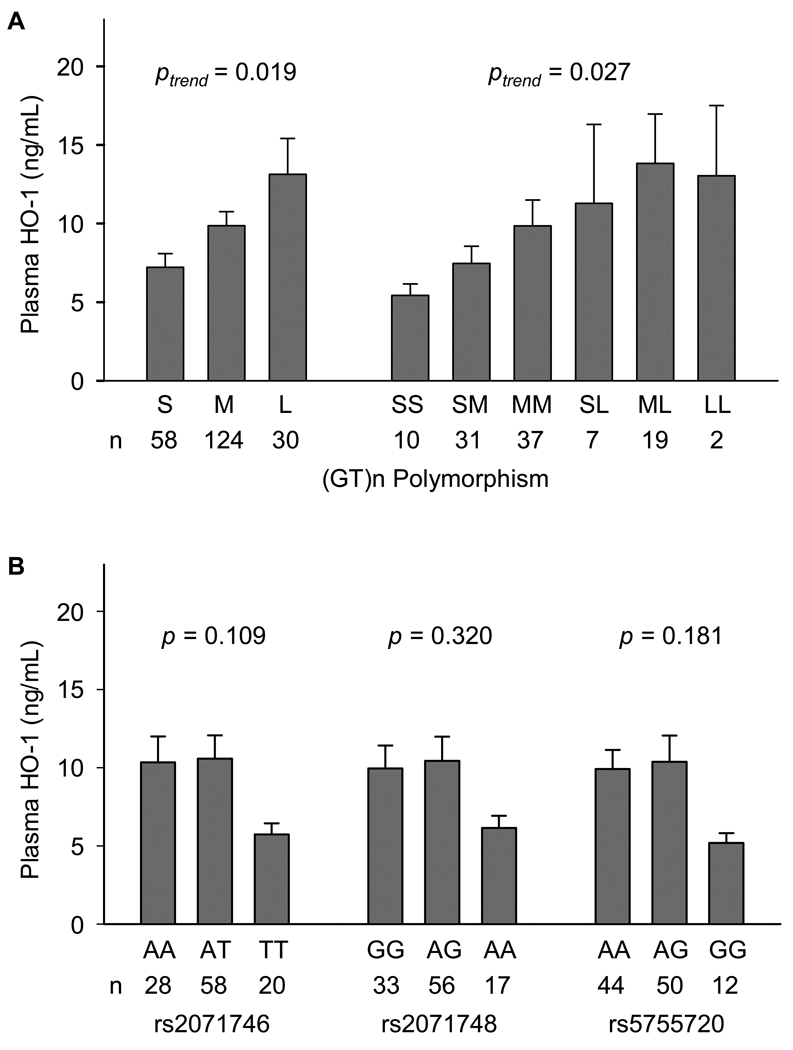

The plasma HO-1 levels among different HMOX1 genotypes in ARDS patients are shown in Fig. 2. We found that longer (GT)n repeats were associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels (Ptrend = 0.019 for allele analysis and 0.027 for genotype analysis). Although patients with variant homozygotes of the three tSNPs had lower plasma HO-1 levels than those with wildtype alleles, the differences did not reach statistical significance. In haplotype analysis, only one common haplotype L-AGA was positively associated with plasma HO-1 levels (P = 0.002) (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Plasma heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) levels among different HMOX1 genotypes in 106 patients with ARDS. A. (GT)n polymorphism. B. Tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs). Data are expressed in plasma HO-1 levels (ng/mL) and indicate mean + SE of each allele type or genotype. The effects of HMOX1 genetic variation on plasma HO-1 were tested in linear regression models, in which the dependent variable, plasma HO-1, were Box-Cox transformed (λ = −0.2) to comply with normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov equality-of-distributions test, P > 0.15). For (GT)n polymorphism, the P values for trend (Ptrend) were calculated. For tSNPs, the P values were calculated based on the additive model, indicating the effects of numbers of copies of the minor alleles.

Table 5.

Regression analysis of correlation between HMOX1 haplotypes and plasma heme oxygenase-1 levels in 106 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome

| Haplotypes | Coefficient (SE) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|

| M-AGA | −0.022 (0.159) | 0.888 |

| S-TAG | −0.299 (0.161) | 0.066 |

| M-TAG | 0.183 (0.264) | 0.489 |

| L-AGA | 0.778 (0.252) | 0.003* |

| M-TAA | 0.144 (0.356) | 0.686 |

HMXO1 heme oxygenase-1 gene; SE standard error: S short; M middle; L long

Analyzed in a linear regression model, where the dependent variable, plasma HO-1 levels, were transformed to normality by Box-Cox transformation (λ = −0.2).

FDR adjusted P value < 0.05

Discussion

In this study, we found that longer (GT)n repeats in the HMOX1 gene promoter were associated with reduced ARDS risk, and the haplotype S-TAG was associated with increased ARDS risk. These associations remain significant after correction for multiple testing. Analysis of association with the intermediate phenotype, plasma HO-1, further supports our findings. Longer (GT)n repeats were associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels, thus providing protection against ARDS. The tSNPs, however, were not independently associated with plasma HO-1 levels or ARDS risk.

The distribution of (GT)n repeats in our study population was consistent with previous reports in Caucasians [29–31]. Although this polymorphism has been studied extensively, the standard cutoffs for grouping the (GT)n repeats remain inconclusive. In this study, we performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the best-fit cutoffs. We also did a thorough review and reclassified the (GT)n repeats according to the two most commonly used grouping criteria. Our results were robust, consistently showing that longer repeats were associated with reduced ARDS risk. The best-fit cutoffs we found in this study just reflected the two peaks of 23 and 30 repeats. However, this classification needs to be validated in other studies.

Our results showed that longer (GT)n repeats were associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels and might protect against ARDS. Such functional significance, although being highly internally consistent in this study, is contrary to most previous reports that shorter (GT)n repeats are associated with higher transcriptional activity, higher HO-1 enzymatic activity, and thus less susceptibility to diseases. Several explanations for the apparent difference are plausible. First, most functional analyses were carried out in vitro by using the transient-transfection assay [16, 19], or by determining the HO-1 expression in specific cells culture [17–19]. However, a promoter assay in vitro does not necessarily represent the gene expression in vivo. Second, regulation of promoter activity by the length of (GT)n repeats may differ in cell types in response to stimuli [18, 19], and the influence of a specific allele on the promoter activity may change during inflammatory conditions [32]. Third, many HMOX1 association studies were conducted in Japanese and Chinese populations. The impact of genetic variation on disease risk may differ among ethnic groups. Noticeably, the presumed protective SS genotype has been associated with higher risk for malignant melanoma [33], cerebral malaria [23], and idiopathic recurrent miscarriage [22]. In addition, some studies showed that the LL genotype, although not statistically significant, may protect against certain diseases [30, 34, 35]. To date, the precise molecular mechanisms by which the (GT)n repeats modulate the expression of HO-1 remain unknown. Some investigators argue that the alternating purine-pyrimidine sequences have the potential to assume Z-DNA, which exerts a negative effect on transcription [36]. However, longer promoter microsatellite dinucleotide repeats do not necessarily down-regulate the promoter activity (ESM11).

Another possible explanation is that our intermediate phenotype plasma HO-1 protein might not be a good surrogate for lung HO-1 expression, as it could simply reflect the level of tissue damage rather than the HO-1 synthesis. Thus the shorter (GT)n repeats might still be associated with increased tissue HO-1 expression, as would be expected. Excessive induction of HO-1 may be deleterious in critically ill patients [37], possibly through the release of free iron and iron-catalyzed oxidative damage. Studies have shown that changes in plasma and lung iron homeostasis are important in the development and propagation of acute lung injury [38]. Variation in iron homeostasis genes like ferritin light-chain (FTL) and heme oxgenase-2 (HMOX2) has been associated with ARDS [39]. Our findings further support that these iron-handling genes might participate in the pathogenesis of ARDS.

In addition to the (GT)n polymorphism, rs2071746 (−413A>T) has also been associated with HMOX1 promoter activity and is considered dominant over the (GT)n repeats [31, 40]. Our data, however, indicate a functional dominance of the (GT)n repeats over rs2071746 (see ESM12 for the detailed discussion).

A major strength of this study is that it was conducted within a large, well-defined, prospectively enrolled cohort of patients at risk for ARDS. The restriction of our analysis to Caucasians and the use of at-risk patients as controls also minimized the possible confounding from either ethnicity or the genetic associations with predisposing conditions of ARDS like sepsis or pneumonia. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating both (GT)n polymorphism and tSNPs in HMOX1. We reported the LD between (GT)n polymorphism and tSNPs for the first time. In addition, we also measured plasma HO-1 as an intermediate phenotype to analyze the functional significance of HMOX1 polymorphisms in ARDS patients. Our results were very consistent. The findings from genotype and haplotype analyses were consonant with each other, and the genotype-phenotype and genotype-disease associations were in a concordant direction.

One of the limitations in this study is that we measured plasma HO-1 in a mere subset of ARDS patients due to availability of acute-phase plasma samples. Although the genotype distributions were not different between patients with and without plasma samples tested, there might remain selection bias in the association of HMOX-1 variants with plasma HO-1. Moreover, we were not able to access the association between plasma HO-1 levels and ARDS development because this plasma subset is a case-only subgroup. Another concern is the correspondence between plasma and tissue (lung) HO-1 expressions in response to stress, which need to be investigated. Finally, our results were based on a single population, thus need to be validated in other populations.

Conclusion

Longer (GT)n repeats in the HMOX1 promoter are associated with higher plasma HO-1 levels and reduced ARDS risk. The common haplotype S-TAG is associated with increased ARDS risk. Nevertheless, no individual tSNP is associated with plasma HO-1 levels or ARDS risk. Our results suggest that HMOX1 variation may modulate the plasma HO-1 levels and ARDS risk through the promoter microsatellite polymorphism. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings. The standard classification of (GT)n repeats and the correspondence of HO-1 levels in plasma and tissues also need to be investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants HL60710 and ES00002 from National Institutes of Health, USA. The authors would like to thank Weiling Zhang, Kelly McCoy, Thomas McCabe, Julia Shin, and Hanae Fujii-Rios for patient recruitment; Andrea Shafer and Starr Sumpter for research support; Maureen Convery for laboratory expertise; Janna Frelich for data management; and the patients and staff of ICUs at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnotes

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Chau-Chyun Sheu, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan; Faculty of Respiratory Therapy, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan.

Rihong Zhai, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA.

Zhaoxi Wang, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA.

Michelle N. Gong, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; NY 10029, USA

Paula Tejera, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA.

Feng Chen, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA.

Li Su, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA.

B. Taylor Thompson, Pulmonary and Critical Care Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

David C. Christiani, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, 665 Huntington Avenue, MA 02115, USA Pulmonary and Critical Care Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

References

- 1.Rubenfeld GD, Herridge MS. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute lung injury. Chest. 2007;131:554–562. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredenburgh LE, Perrella MA, Mitsialis SA. The role of heme oxygenase-1 in pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:158–165. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0331TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morse D, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1: from bench to bedside. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:660–670. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-465SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crimi E, Sica V, Williams-Ignarro S, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Ignarro LJ, Napoli C. The role of oxidative stress in adult critical care. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang JD, McArdle PJ, O'Reilly PJ, Matalon S. Oxidant-antioxidant balance in acute lung injury. Chest. 2002;122:314S–320S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.314s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mumby S, Upton RL, Chen Y, Stanford SJ, Quinlan GJ, Nicholson AG, Gutteridge JM, Lamb NJ, Evans TW. Lung heme oxygenase-1 is elevated in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1130–1135. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000124869.86399.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otterbein LE, Lee PJ, Chin BY, Petrache I, Camhi SL, Alam J, Choi AM. Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest. 1999;116:61S–63S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.61s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryter SW, Kim HP, Nakahira K, Zuckerbraun BS, Morse D, Choi AM. Protective functions of heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the respiratory system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2157–2173. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otterbein LE, Kolls JK, Mantell LL, Cook JL, Alam J, Choi AM. Exogenous administration of heme oxygenase-1 by gene transfer provides protection against hyperoxia-induced lung injury. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1047–1054. doi: 10.1172/JCI5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor JL, Carraway MS, Piantadosi CA. Lung-specific induction of heme oxygenase-1 and hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L582–L590. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otterbein L, Sylvester SL, Choi AM. Hemoglobin provides protection against lethal endotoxemia in rats: the role of heme oxygenase-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:595–601. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.5.7576696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredenburgh LE, Baron RM, Carvajal IM, Mouded M, Macias AA, Ith B, Perrella MA. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 expression in the lung parenchyma exacerbates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury and decreases surfactant protein-B levels. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2005;51:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita T, Toda K, Karimova A, Yan SF, Naka Y, Yet SF, Pinsky DJ. Paradoxical rescue from ischemic lung injury by inhaled carbon monoxide driven by derepression of fibrinolysis. Nat Med. 2001;7:598–604. doi: 10.1038/87929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryter SW, Morse D, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide and bilirubin: potential therapies for pulmonary/vascular injury and disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:175–182. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0333TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YH, Lin SJ, Lin MW, Tsai HL, Kuo SS, Chen JW, Charng MJ, Wu TC, Chen LC, Ding YA, Pan WH, Jou YS, Chau LY. Microsatellite polymorphism in promoter of heme oxygenase-1 gene is associated with susceptibility to coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetic patients. Hum Genet. 2002;111:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0769-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirai H, Kubo H, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, Numasaki M, Kobayashi S, Suzuki S, Shibahara S, Sasaki H. Microsatellite polymorphism in heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter is associated with susceptibility to oxidant-induced apoptosis in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Blood. 2003;102:1619–1621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rueda B, Oliver J, Robledo G, Lopez-Nevot MA, Balsa A, Pascual-Salcedo D, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Escribano MF, Martin J. HO-1 promoter polymorphism associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3953–3958. doi: 10.1002/art.23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada N, Yamaya M, Okinaga S, Nakayama K, Sekizawa K, Shibahara S, Sasaki H. Microsatellite polymorphism in the heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter is associated with susceptibility to emphysema. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:187–195. doi: 10.1086/302729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasuda H, Okinaga S, Yamaya M, Ohrui T, Higuchi M, Shinkawa M, Itabashi S, Nakayama K, Asada M, Kikuchi A, Shibahara S, Sasaki H. Association of susceptibility to the development of pneumonia in the older Japanese population with haem oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e17. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam T, McConnell R, Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Peters JM, Gilliland FD. Ozone, oxidant defense genes, and risk of asthma during adolescence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-863OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denschlag D, Marculescu R, Unfried G, Hefler LA, Exner M, Hashemi A, Riener EK, Keck C, Tempfer CB, Wagner O. The size of a microsatellite polymorphism of the haem oxygenase 1 gene is associated with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:211–214. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda M, Kikuchi M, Ubalee R, Na-Bangchang K, Ruangweerayut R, Shibahara S, Imai S, Hirayama K. Microsatellite polymorphism in the heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter is associated with susceptibility to cerebral malaria in Myanmar. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2005;58:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, Pothier L, Boyce PD, Christiani DC. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, LeGall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. Report of the American-European consensus conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes and clinical trial coordination. The Consensus Committee. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:225–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01704707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eide IP, Isaksen CV, Salvesen KA, Langaas M, Schonberg SA, Austgulen R. Decidual expression and maternal serum levels of heme oxygenase 1 are increased in pre-eclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:272–279. doi: 10.1080/00016340701763015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirino Y, Takeno M, Iwasaki M, Ueda A, Ohno S, Shirai A, Kanamori H, Tanaka K, Ishigatsubo Y. Increased serum HO-1 in hemophagocytic syndrome and adult-onset Still's disease: use in the differential diagnosis of hyperferritinemia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R616–R624. doi: 10.1186/ar1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato T, Takeno M, Honma K, Yamauchi H, Saito Y, Sasaki T, Morikubo H, Nagashima Y, Takagi S, Yamanaka K, Kaneko T, Ishigatsubo Y. Heme oxygenase-1, a potential biomarker of chronic silicosis, attenuates silica-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:906–914. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1237OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiroch K, Koch W, von Beckerath N, Kastrati A, Schomig A. Heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism and restenosis following coronary stenting. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:968–973. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Courtney AE, McNamee PT, Middleton D, Heggarty S, Patterson CC, Maxwell AP. Association of functional heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism with renal transplantation outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:908–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buis CI, van der Steege G, Visser DS, Nolte IM, Hepkema BG, Nijsten M, Slooff MJ, Porte RJ. Heme oxygenase-1 genotype of the donor is associated with graft survival after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:377–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright EK, Jr, Page SH, Barber SA, Clements JE. Prep1/Pbx2 complexes regulate CCL2 expression through the −2578 guanine polymorphism. Genes Immun. 2008;9:419–430. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamoto I, Krogler J, Endler G, Kaufmann S, Mustafa S, Exner M, Mannhalter C, Wagner O, Pehamberger H. A microsatellite polymorphism in the heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter is associated with risk for melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1312–1315. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He JQ, Ruan J, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, Pare PD, Sandford AJ. Antioxidant gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to a rapid decline in lung function in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:323–328. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2111059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ullrich R, Exner M, Schillinger M, Zuckermann A, Raith M, Dunkler D, Horvat R, Grimm M, Wagner O. Microsatellite polymorphism in the heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter and cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1600–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naylor LH, Clark EM. d(TG)n.d(CA)n sequences upstream of the rat prolactin gene form Z-DNA and inhibit gene transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1595–1601. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melley DD, Finney SJ, Elia A, Lagan AL, Quinlan GJ, Evans TW. Arterial carboxyhemoglobin level and outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1882–1887. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275268.94404.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lagan AL, Melley DD, Evans TW, Quinlan GJ. Pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory syndrome and acute lung injury: role of iron mobilization and decompartmentalization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L161–L174. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagan AL, Quinlan GJ, Mumby S, Melley DD, Goldstraw P, Bellingan GJ, Hill MR, Briggs D, Pantelidis P, du Bois RM, Welsh KI, Evans TW. Variation in iron homeostasis genes between patients with ARDS and healthy control subjects. Chest. 2008;133:1302–1311. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono K, Goto Y, Takagi S, Baba S, Tago N, Nonogi H, Iwai N. A promoter variant of the heme oxygenase-1 gene may reduce the incidence of ischemic heart disease in Japanese. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.