Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify kindergarten-age predictors of early-onset substance use from demographic, environmental, parenting, child psychological, behavioral, and social functioning domains. Data from a longitudinal study of 295 children were gathered using multiple-assessment methods and multiple informants in kindergarten and 1st grade. Annual assessments at ages 10, 11, and 12 reflected that 21% of children reported having initiated substance use by age 12. Results from longitudinal logistic regression models indicated that risk factors at kindergarten include being male, having a parent who abused substances, lower levels of parental verbal reasoning, higher levels of overactivity, more thought problems, and more social problem solving skills deficits. Children with no risk factors had less than a 10% chance of initiating substance use by age 12, whereas children with 2 or more risk factors had greater than a 50% chance of initiating substance use. Implications for typology, etiology, and prevention are discussed.

Keywords: early-onset substance use, children, development, etiology

Introduction

Experimentation with alcohol and drugs during adolescence is a statistically normative phenomenon. Most adolescents tend to initiate the use of alcohol between the ages of 13 and 15 (O'Malley, Johnston, & Bachman, 1998), and a recent Monitoring the Future study found that 54% of graduating seniors reported having tried an illicit drug (University of Michigan, 1998). As a normative phenomenon, alcohol and drug use in late adolescence is not strongly associated with problematic outcomes. However, the earlier a child initiates the use of alcohol or drugs, the greater is his or her risk of becoming involved in a wide range of problem outcomes, including aggression, school failure, delinquency, and especially later problem use and abuse of substances (Jackson, Henriksen, Dickinson, & Levine, 1997; Kandel, 1982; Robins & Przybeck, 1985). Because early experimentation with substances appears to be a critical precursor of later substance abuse, it is important to determine which factors are most likely to contribute to children's early initiation of substance use. In contrast to broad empirical evidence linking early-onset substance use with later problem outcomes, much less is known about the development and etiology of early substance use initiation. The identification of prospective predictors of early substance use initiation is the focus of the current paper.

Given the scarcity of studies examining the initiation of substance use prior to adolescence, further research is needed to understand the extent to which different psychosocial domains contribute to the prediction of early-onset substance use and whether these predictors change in salience over the course of development. Research has found that some risk factors predict dysfunction only at specific periods of development, whereas others are relatively stable predictors of disorder across the life span (Coie et al., 1993). A prime example is conduct disorder, for which predictors of early-onset aggressive behavior differ from those of adolescent-limited delinquency (Moffitt, 1993). Thus, the main goals of this study were to identify predictors of early-onset substance use from a range of psychosocial domains and to determine whether predictors of adolescent substance use identified in previous empirical studies would also predict the initiation of early-onset substance use in the current sample. Theories such as the multistage social learning model (Simons, Conger, & Whitbeck, 1988), the social development model (Hawkins & Weis, 1985), and family interaction theory (Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990) suggest that parenting behaviors have the most impact during childhood and adolescence whereas the influences of peers and the larger social environment increase with age (Simons, Conger, & Whitbeck, 1988). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the major predictors of early-onset substance use will be related to parenting and child functioning as opposed to more distal factors such as the neighborhood environment or social status among peers.

Patterns of drug use are determined by many factors, and any model that purports to offer a comprehensive explanation of substance use will necessarily be complex, containing a number of variables (Simons et al., 1988). In addition, in order to establish a particular variable as a risk factor, studies must be truly prospective by interviewing participants before they have initiated substance use (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1999). In an effort to address the complexity involved in the prediction of early-onset substance use, the current article includes a wide range of kindergarten and first grade predictor variables drawn from theory (i.e., multistage social learning model; Simons et al., 1988) as well as past empirical evidence. It is important to note that this study examines preadolescent children's initiation of substance use, and does not examine substance abuse or dependence. However, because of the fact that almost no studies to date have focused on children's early initiation of substance use (i.e., prior to adolescence), most of the theoretical and empirical bases for the hypotheses of this paper will be drawn from the adolescent substance use and abuse literature.

Adolescent-Onset Substance Use

A thorough review of all existing theories of adolescent substance use is beyond the scope of this paper (see Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). This study relies upon the theoretical work of Simons et al. (1988) as well as related empirical research as a foundation for the hypotheses tested. The multistage social learning model (Simons et al., 1988) posits that adolescents' involvement in substance use is a result of several social learning processes (e.g., parenting practices and parental substance use) as well as intrapersonal characteristics (emotional distress, inadequate coping skills, and deficient social skills). This theoretical model was chosen because it is one of the most comprehensive theories of adolescent substance use in its attempt to integrate individual, parent, and peer characteristics into a single model (Petraitis et al., 1995). In support of this theoretical model, recent research has identified a number of factors across several domains of functioning that are predictive of initiation of substance use in adolescence including parent, child, and social influences. These findings and their theoretical underpinnings are described below.

Parenting Practices

The multistage social learning model (Simons et al., 1988) asserts that children often acquire substance using behaviors through modeling of the parent's own behaviors as well as the quality of the parent–child relationship. Research on modeling shows that individuals are most likely to emulate the actions of others whom they hold in high esteem (Bandura, 1977). Consequently, parents who maintain a warm, nurturing relationship with their children are most likely to influence their children's values and behavior positively (Conger, 1976). Similarly, it is not enough for parents to hold certain values about the use of substances; children are less likely to adopt the values of parents who are rejecting, emotionally unavailable, or overly controlling/authoritarian (Simons et al., 1988).

Parental Mental Health History

Although children are more likely to model parental behaviors if a positive relationship has been established (Bandura, 1977), children have been found to emulate parental behaviors regardless of the quality of the parent–child relationship. For example, research has found that children of substance-abusing parents are at higher risk than children of nonabusing parents for initiation of substance use (Costello, Erkanli, Federman, & Angold, 1999; Jackson, Henriksen, Dickinson, & Levine, 1997) and escalation of alcohol use (Chassin, Curran, Hussong, & Colder, 1996). Studies have been unable to determine whether this positive relation is due to direct modeling of parental behavior or to parental unavailability (e.g., parental depression) that is often associated with parental substance abuse. Indeed, a lack of parental involvement has been associated with adolescent substance use (Baumrind, 1985; Patterson, 1982), and it is thought that adolescents are more likely to emulate the actions of deviant peers (e.g., engage in early substance use) if a parent is physically and emotionally unavailable. Because of the complex relations between parenting practices, parental psychopathology, and children's initiation of early substance use, this study examines the unique effects of variables from each of these domains. Specifically, this study examines parenting practices (i.e., warmth, verbal reasoning, use of physical punishment), parental psychopathology (i.e., depressive symptoms), parental involvement (i.e., parental involvement in the school), and parental substance abuse as potential predictors of early-onset substance use.

Child Psychological and Behavioral Functioning

The multistage social learning model posits that adolescents who are emotionally distressed may turn to substances as a means of temporarily relieving their anxiety or depressive symptoms (Simons et al., 1988). This is similar to the self-medication model commonly found in the adult literature, which posits that individuals with internalizing problems will utilize substances in an effort to dampen their negative affect (Sher, 1991). However, there is empirical evidence to suggest that different dimensions of internalizing symptoms are differentially related to substance use. For example, whereas depressive symptoms and generalized anxiety symptoms have been found to be positively related to the initiation of alcohol use in adolescence, separation anxiety symptoms have been associated with a decreased likelihood of substance use initiation (Hussong & Chassin, 1994; Kaplow, Curran, Angold, & Costello, 2001).

The multistage social learning model focuses less on externalizing behaviors as causal factors in substance use compared with some other theories (e.g., problem-behavior theory; Jessor & Jessor, 1977) that assert that child temperament (i.e., behavioral disinhibition) and problematic parent–child relationships lead to disruptive behaviors in children. Children with disruptive behaviors are then more likely to affiliate with a deviant peer group that supports delinquency and substance-using behavior (Jessor & Jessor, 1977;Lerner, 1984). Research has found that sensation seeking (Wills, Vaccaro, & McNamara, 1994) and temperamental difficulties (Lerner, 1984) are associated with adolescent substance use. In addition, conduct problems in adolescence predict the initiation of alcohol use as well as greater escalations of alcohol use over time (Costello et al., 1999; Hussong, Curran, & Chassin, 1998). It is important to note, however, that certain dimensions of externalizing behavior do not appear to be associated with substance use in adolescence. For example, a recent study found that symptoms of inattention were unrelated to substance use in adolescents, whereas dimensionally scored impulsivity–hyperactivity symptoms were positively related to adolescent substance use (Molina, Smith, & Pelham, 1999).

By examining clusters of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as predictors, as opposed to disaggregating different dimensions of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, important predictor variables may be overlooked. Thus, this study uses narrow band scales of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology to test their unique effects on early-onset substance use.

Social Contexts

The multistage social learning model asserts that an important factor in escalation of adolescent substance use is having peers who encourage and engage in substance use (Simons et al., 1988). Adolescents who are most likely to affiliate with a deviant peer group are those who have social skills deficits (e.g., impolite, uncompromising, unempathic) and are not well liked by other children. Research has found that one of the strongest predictors of adolescent-onset substance use is affiliation with a substance-using peer group, and most adolescent substance use takes place within a social context (Clark, Parker, & Lynch, 1999; Oetting & Beauvais, 1987). Additionally, larger social systems such as the neighborhood environment have been found to predict initiation of adolescent substance use by providing exposure and access to substances and substance-using peers (Sampson, 1997). Thus, the current study uses ratings of peer sociometric status as well as neighborhood environment to test these influences on early-onset substance use.

Child Social Adaptation

Social learning theory posits that youth learn strategies for coping with stress from their adult caregivers through observation and modeling (Bandura, 1977). Research has suggested that both adults and adolescents who abuse substances lack effective coping skills (Pentz, 1985; Wills & Filer, 1996). The multistage social learning model proposes that children with a limited repertoire of coping skills will tend to respond to stress with strategies involving avoidance and distraction (e.g., substance abuse), similar to the strategies employed by their parents (Simons et al., 1988). The model also suggests that children with social skills deficits (inability to resolve conflict, difficulty mobilizing social support) will have problems coping in social situations, and will be more likely to use alcohol as a coping strategy (Simons et al., 1988). This study examines variables related to social and emotional coping skills as potential predictors of early-onset substance use.

Early-Onset Substance Use

Although it is clear that the prediction of adolescent substance use involves numerous factors from different psychosocial domains, it has been hypothesized that some of these factors may not be as important in predicting early onset of substance use prior to adolescence (Kandel, 1982). Very few studies have examined potential risk factors for early-onset substance use, with even fewer studies utilizing a developmental perspective and prospective longitudinal designs. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether risk factors for onset of substance use vary as a function of developmental stage. The implications of a developmental distinction between preadolescent and adolescent-onset substance use for typology, etiology, and prevention are enormous.

Of the few studies that have examined early-onset substance use, findings have been similar to those derived from adolescent studies. For example, parental use of substances (Costello et al., 1999) and child temperamental characteristics (Masse & Tremblay, 1997) have been identified as important predictors of early-onset substance use. In addition to these predictors, the multistage social learning model suggests that other factors such as child psychological functioning, child social adaptation, parenting practices, and parent psychological functioning are likely to be related to the early initiation of substance use, but have yet to be tested empirically. These are the goals of this study.

This study is unique for several reasons. First, with few exceptions (e.g., Masse & Tremblay, 1997), it is one of the only studies to examine kindergarten predictors of initiation of substance use prior to age 12, allowing for the identification of truly prospective relations as assessed prior to the onset of first time use. Second, the predictors span a number of different areas of functioning including environmental, child, parent, and peer domains. Third, multiple informants are used to measure the constructs of interest. Finally, the sample includes boys and girls from four culturally and geographically diverse American communities, allowing for the examination of potential gender, ethnic, or geographic effects on early onset of substance use.

Method

Participants

This study utilized data from a community-based sample of children (N = 295) drawn from the normative sample of the Fast Track Project, a longitudinal multisite investigation of the development and prevention of conduct problems in childhood (see Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992, for full details regarding study design and instruments). Participants were initially interviewed during the spring of the children's kindergarten year and were followed for 7 years. Subjects were selected from four different areas of the country: (1) Durham, NC; (2) Nashville, TN; (3) Seattle, WA; and (4) Central Pennsylvania. These areas were selected in order to represent different cross-sections of the American population. Within each site, schools with high rates of children at risk for the development of conduct problems were sampled (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992).

As part of the intervention study design, a normative sample of children was selected in order to compare subsequent improvements made by the intervention group against a normative standard. From these schools, 100 kindergarten children were selected at each site (87 in Seattle because of one school dropping out during the 1st year) to represent the population distribution in terms of race, gender, and level of teacher-reported behavior problems. To obtain a representative sample in terms of teacher-reported behavior problems, the normative sample of 100 children from each site was selected by including 10 children from each decile of the distribution of scores on a teacher-report screen for behavior problems (i.e., Authority Acceptance score of the Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation—Revised; TOCA-R; Werthamer-Larsson & Kellam, 1989). These children were then approached randomly to participate in a descriptive longitudinal study. Nonparticipants were replaced by matched children until the sample reached an n of 100 per site (n = 87, in Seattle).

In this study, 92 participants (24% of the entire sample) were eliminated because of missing data on the outcome variable, substance use (attrition analyses are presented later). In addition, if any of the 295 children with complete substance use data were missing data on other measures used in a particular model, these subjects were eliminated from that particular analysis. Among the 295 children included in the current sample, the mean age at the initial time point was 6.37 (SD = 0.46), the mean age at outcome was 12.37,51% were girls, 46% were African American, 52% were Caucasian, and 2% were other ethnic minorities. Approximately 48% of the children came from two-parent families, 45% came from mother-headed families, and 7% were missing data on this variable. Using the Hollingshead four-factor categorization system of the education and occupation of the head of household (mothers in mother-headed families and the mean of mother and father in two-parent families), the mean socioeconomic status SES was 26.6 (SD = 13.8), which is the low-middle class with a range from the lowest class to middle class.

Measures

All of the following variables, with the exceptions of teacher-report variables, sociometric ratings, history of medication for ADHD, and child substance use, were taken from measures initially administered to the normative sample of children in 1991 (Year 1) during a 2-hr home visit with interviews and direct observations of mothers and children during the summer after kindergarten. Teachers reported on children's externalizing symptoms and parent–school involvement during the kindergarten year. The sociometric variables were gathered from this sample for the first time in Grade 1 in 1992 (Year 2). The history of medication for ADHD was assessed for the first time in Grade 3 in 1994 (Year 4). The substance use measures of interest were administered at the conclusion of Grades 4, 5, and 6 in 1995 (Year 5), 1996 (Year 6), and 1997 (Year 7), respectively. The vast majority of parent-report measures were completed by the mother.

Because there is sufficient empirical evidence to suggest that not all sources of information are equally useful or valid for the assessment of certain behaviors (Loeber, Green, Lahey, Stouthamer-Loeber, 1989), only those informants who have been found to be the most valid in their ratings of specific childhood behaviors were utilized. For example, whereas teachers have been found to be more valid reporters of children's delinquent behavior than parents or children (Hart, Lahey, Loeber, & Hanson, 1994), many conduct problems of a concealing nature such as substance use are more valid coming from the children themselves (Loeber et al., 1989).

Home and Neighborhood Environment

Ratings of the quality of the home and neighborhood environments were completed by each of the interviewers during the home visit through the use of the Post-Visit Inventory, a survey reflecting the interviewer's ratings of the physical environment in the home and neighborhood (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990). Response options ranged from dichotomous “yes or no” answers to 4-point scale responses, with higher scores indicating greater problems or risk in the physical context. Principal component analysis of items resulted in two factors that were labeled Home Environment (3 items, α = .63, e.g., How many rooms are in this dwelling?) and Neighborhood Environment (4 items, α = .75, e.g., How safe/dangerous is the area outside of this dwelling?). Interrater reliability was assessed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). The ICC for Home Environment was .85 and the ICC for Neighborhood Environment was .88.

Parenting Practices and Parent Mental Health History

Several measures of parenting practices were administered. The Parent Questionnaire is a 27-item adaptation of the Parent Practices Scale (Strayhorn & Weidman, 1988). The current study utilized the Parental Warmth scale, a five-item scale (α = .76) that asks the mother to rate the frequency of different behaviors on a 5-point scale (e.g., How often do you praise your child? How often do you and your child laugh together?).

During the home visit, a structured 18-min parent–child interaction task (PCIT) was completed, during which the mother and child were asked to play together, build a toy structure, and clean up. Interviewers were trained to observe and code specific behaviors during each task. At the conclusion of each task in the PCIT, the interviewer completed an adaptation of the Interaction Rating Scales (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990), which consists of 16 global 5-point items assessing the observed interactions of the mother and child. Of interest in this study is the interviewer rating of physical punishment, in which higher scores represent greater use of physical punishment.

The Developmental History (adapted from Dodge et al., 1990) is an orally administered interview that focuses on family experiences over the past 12 months. As part of the Insights section of the interview, mothers in this study were presented with six brief written vignettes of various child misbehaviors (e.g., when the child does not go to bed on time) and were asked to describe what he/she would do in that situation. Interviewers coded the frequency with which mothers mentioned certain parenting techniques, ranging from reasoning to physical punishment. Of interest in this study is mothers' mean score for verbal reasoning (α = .66), with higher scores indicating more frequent use of verbal reasoning.

The Parent–Teacher Involvement Questionnaire—Teacher (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999) is a 26-item measure that assesses the amount and quality of contact that occurred between the mother and teacher. Kindergarten teachers rated parental behaviors on a 5-point scale. Of interest in this study is the Parent–School Involvement Scale (α = .89), with higher scores on this measure indicating greater parental involvement in school.

Mothers also completed self-reports of their own psychological functioning. Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The scale measures major components of depressive symptomatology, and respondents are asked to rate the frequency of each of 20 symptoms experienced in the previous 7 days on a 4-point scale. This study also utilized the Family Information Form (FIF; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999), a survey administered to the mother during the interview that assesses any mental health problems that either parent may have experienced throughout the previous year. Of interest in this study are two items inquiring about any alcohol or drug problems, coded dichotomously (0 = no, 1 = yes). The two items were combined to form an overall measure of any parental substance abuse.

Child Psychological and Behavioral Functioning

Children were administered two subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Revised (WISC-R; Wechsler, 1974): Vocabulary and Block Design. This test was administered twice, once after kindergarten and once after first grade. Children's scores on each subtest were combined within year and these two IQ scores from kindergarten and first grade were averaged to yield an overall/composite IQ score for each child.

The kindergarten teacher completed the child attention profile (CAP; Barkley, 1988) to assess child inattention and overactivity. The CAP scale is derived from 12 items on the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991): seven inattention items and five overactivity items, with higher scores indicating greater levels of inattention and overactivity, respectively. Internal consistency of the CAP has been reported to be quite satisfactory (split-half r = .84). Interrater reliability for boys aged 6–11years using teacher reports has been found to be .77(n = 37). The scale significantly discriminates referred and nonreferred children (N = 2,200) from the standardization sample and has been shown to be highly sensitive to dose effects of stimulant drugs with ADD children (Barkley, McMurray, Edelbrock, & Robbins, 1989).

When children were in the third grade, mothers were asked whether their child had ever taken Ritalin or any other medication for ADHD symptoms. Scores were coded dichotomously as 0 = no, 1 = yes.

Several measures were used to assess child aggressive/oppositional behaviors. The Parent Daily Report (PDR; Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) is a 30-item checklist that assesses child oppositional behavior. Mothers completed this measure on three different occasions (during the initial interview before kindergarten, 1 week following the interview, and 1 week after that) during which time they indicated whether or not 30 different behavioral problems had occurred over the previous 24-hr period, using a dichotomous scale (did or did not occur). Preliminary factor analysis of the PDR identified 15 behaviors that factored onto two scales reflecting six aggressive behaviors, e.g., fighting, yelling; (α = .83) and nine oppositional behaviors, e.g., talking back, noncompliance; (α = .81). Reports of the 15 aggressive and oppositional behaviors were summed over the three administrations of the PDR providing a total home-setting problem behavior score.

In order to assess children's externalizing behavior in the school context, two scales of the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991) provided information regarding teachers' perceptions of child externalizing behavior: Aggressive (20 items) and Delinquent (13 items) Behavior scales. Using a 3-point rating system, teachers rated the extent to which each child engaged in a number of different aggressive and delinquent behaviors, with higher scores indicating greater aggressive and delinquent behaviors.

Internalizing symptoms were assessed with the mother-rated child behavior checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991), a highly reliable and valid 113-item symptom checklist that assesses internalizing and externalizing symptoms of the child by the parent using a 3-point rating system. The current study utilized mothers' ratings in kindergarten from the following scales: Somatic Complaints (9 items), Thought Problems (7 items), Withdrawn (9 items), and Anxiety/Depression (14 items).

Child Social and Emotional Adaptation

This study utilized three measures to assess child social skills. The Emotion Recognition Questionnaire (Ribordy, Camras, Stefani, & Spaccarelli, 1988) consists of 16 different vignettes. Each child was asked to point to one of four pictures correctly indicating the emotion that is likely to be elicited in each context. The emotion recognition score has adequate construct validity and reliability (α = .66), with higher scores reflecting greater emotion recognition.

The Social Problem-Solving measure (Dodge et al., 1990) consists of a series of eight drawings and vignettes about common social problems. Each child was asked to describe what the character should do to solve the problem. Responses are coded as prosocial/competent or aggressive/inept, and a score reflecting the proportion of competent responses (α = .70) was derived, with higher scores indicating greater social competence. Interrater agreement was assessed for 15% of the sample by having an independent rater code transcribed responses and was excellent (κ = .94).

The Home Inventory with Child (Dodge et al., 1990) assesses children's hostile attributional biases. Each child was shown a series of eight drawings and read vignettes depicting either unsuccessful peer entry (e.g., being ignored or rejected) or minor harm under conditions of ambiguous intent (e.g., being pushed or bumped). Interpretations of ambiguous events on this measure were coded as hostile, nonhostile, or don't know/other. The proportion of hostile attributions (α = .80) was computed, with higher scores indicating greater frequency of hostile attributions. Based on examination of 15% of the sample, interrater reliability was excellent (κ = .90).

During the first grade, peer nominations were collected following written parental consent from each classroom peer. Sociometric interviews were completed individually with each peer in classrooms for which at least 70% of peers consented. During the interview, peers were asked to nominate children who fit the following description: “Some kids are really good to have in your class because they cooperate, help others, and share. They let other kids have a turn.” These prosocial nominations were totaled and standardized within each classroom. Children were also asked to nominate an unlimited number of classmates whom they “most liked” and “least liked.” These scores were computed by standardizing the “most liked” and “least liked” nominations within each classroom and calculating the difference between these standard scores (LM-LL). The difference scores were then restandardized to derive a social preference score, with higher scores reflecting greater social status (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999).

Child Substance Use

The Things That You Have Done survey, a 32-item measure derived from the National Youth Survey (Elliot, Ageton, & Huizinga, 1985) and developed for this study assesses a range of antisocial behaviors that the child may have engaged in over the previous year. The items of interest in this study are nine items related to the consumption of any alcoholic beverages or drugs. The questions ask the child whether he or she has consumed any beer, wine, or liquor, marijuana, heroin, crack, cocaine, LSD, or inhalants, and if so, the number of times that this occurred. Tobacco use was not included in the derivation of this construct. Scores on this measure were dichotomized such that any use was coded as 1 and no use was coded as 0. Approximately 7% of the sample reported any alcohol or drug use in fourth grade, 5% of the sample reported any alcohol or drug use in fifth grade, and 14% of the sample reported any alcohol or drug use in sixth grade. Because of the low rates of use within each grade, measures from Grades 4,5, and 6 were combined to form an overall measure of substance use with 0 = no use and 1 = use at any time point. This coding system assumes that no children were using substances in kindergarten and any reports of use by the sixth grade represent initial onset of substance use. In total, 21% of the sample (25 girls and 40 boys) reported initiation of substance use by sixth grade.

Statistical Analysis

A series of five hierarchical, longitudinal logistic regression models was used to test the unique relations between sets of categorical and continuous predictors and early onset of childhood substance use.6 Within each regression model, the dichotomous dependent variable, initiation of substance use by the sixth grade, was first regressed on five covariates (age, gender, race, SES, and site), followed by one or more sets of predictors in the second step. Each set of predictors encompassed one of the following domains: environment, parenting, child psychological and behavioral functioning, and child social functioning. A comprehensive logistic regression model was estimated that included each of the predictors that achieved a p value of .07 or less in one of the four initial regression models, providing a data-informed but rigorous test of the unique predictive utility of each variable. Finally, this comprehensive model was reestimated while controlling for concurrent externalizing symptomatology in the sixth grade in order to ensure that these factors predict substance use in particular and not externalizing behavior in general.

Results

Attrition and Missing Data

In this study, 92 of the 387 original participants (24% of the total sample) were eliminated because of missing data on the outcome variable, substance use. Potential bias due to attrition was assessed by comparing the demographic and predictor variables of the subjects included in the analyses with those that had been excluded from the analyses. A series of χ2 tests and t tests were estimated for this purpose. The results of these analyses indicated that the subjects who were excluded from this study did not differ significantly from those who were included in terms of age, t(385) = 0.55, p = .58; gender, χ2(1, N = 387) = 0.76, p = .38; race, χ2(1, N = 386) = 1.99, p = .16; SES, t(384) = 0.73, p = .47; or any of the predictor variables considered in this study. However, caution is still warranted in generalizing the results of this study.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Relations

Table I shows descriptive statistics and bivariate relations between substance use and all predictor variables.7 Continuous predictors were analyzed using t tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests. It is noteworthy that 17 of the 28 predictor variables were significantly related to the initiation of substance use (p < .05). Early-onset substance use was significantly associated with being male, being African American, low SES, residence in a dangerous neighborhood, problematic parenting (lower levels of verbal reasoning and decreased parental involvement in school), maternal depression, parental substance abuse, several child characteristics (low IQ, higher levels of inattention, overactivity, aggressive behavior, delinquent behavior, and thought problems), receiving medication for ADHD, problematic social cognitions (hostile attributions and poor social problem solving), and peer relations (low social preference and decreased prosocial behavior).

Table I.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Relations Between Predictors and Initiation of Substance Use

| Nonusers | Users | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | Test statistic | p level |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age | 6.35 | 0.45 | 230 | 6.42 | 0.49 | 65 | t = 1.05 | ns |

| Gendera | 0.46 | 0.50 | 230 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 65 | χ2 = 4.54 | .03 |

| Raceb | 0.42 | 0.49 | 230 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 65 | χ2 = 7.58 | .006 |

| SES | 27.37 | 14.07 | 230 | 23.60 | 12.55 | 65 | t = −1.94 | .05 |

| Environment | ||||||||

| Home environment | 8.89 | 2.32 | 221 | 9.46 | 2.24 | 65 | t = 1.79 | .07 |

| Neighborhood environment | 8.70 | 2.56 | 221 | 9.42 | 2.35 | 65 | t = 2.00 | .05 |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Parental warmth | 3.52 | 0.76 | 229 | 3.39 | 0.73 | 65 | t = −1.30 | ns |

| Physical punishment | 2.41 | 1.28 | 230 | 2.69 | 1.33 | 65 | t = 1.54 | ns |

| Verbal reasoning | 0.21 | 0.25 | 230 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 64 | t = −2.52 | .01 |

| Parental involvement in school | 1.17 | 0.64 | 192 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 61 | t = −2.81 | .01 |

| Maternal depression | 12.81 | 8.79 | 230 | 17.13 | 11.49 | 65 | t = 2.79 | .01 |

| Parent substance abusec | 0.15 | 0.36 | 230 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 64 | χ2 = 16.25 | .001 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Child IQ | 96.44 | 18.08 | 230 | 90.53 | 16.06 | 65 | t = −2.37 | .02 |

| Inattention | 4.03 | 4.67 | 191 | 6.00 | 3.96 | 61 | t = 2.95 | .003 |

| Overactivity | 2.68 | 2.98 | 191 | 4.58 | 3.35 | 61 | t = 4.20 | .001 |

| Medication for ADHD | 0.10 | 0.43 | 223 | 0.34 | 0.76 | 64 | χ2 = 10.55 | .001 |

| Oppositional behavior | 0.21 | 0.17 | 230 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 65 | t = .20 | ns |

| Aggressive behavior | 8.15 | 10.46 | 191 | 15.62 | 13.71 | 61 | t = 3.88 | .001 |

| Delinquent behavior | 1.90 | 2.77 | 191 | 3.48 | 3.17 | 61 | t = 3.74 | .001 |

| Somatic complaints | 1.03 | 1.38 | 229 | 1.53 | 2.15 | 65 | t = 1.76 | .08 |

| Thought problems | 0.63 | 1.01 | 229 | 1.22 | 1.49 | 65 | t = 2.96 | .004 |

| Withdrawn | 2.12 | 1.87 | 229 | 2.38 | 2.17 | 65 | t = .92 | ns |

| Anxious/depressed | 3.49 | 3.15 | 229 | 3.80 | 3.39 | 65 | t = .69 | ns |

| Emotion recognition | 11.25 | 2.74 | 228 | 11.03 | 3.12 | 63 | t = −.55 | ns |

| Hostile attributions | 0.60 | 0.30 | 230 | 0.69 | 0.27 | 65 | t = 2.05 | .04 |

| Social problem solving | 0.67 | 0.22 | 230 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 65 | t = −2.21 | .03 |

| Social preference score | 0.09 | 0.98 | 202 | −0.37 | 1.02 | 54 | t = −2.97 | .003 |

| Prosocial score | 0.11 | 1.03 | 202 | −0.36 | 0.90 | 54 | t = −3.06 | .003 |

Note. Sample sizes vary from 252 to 295 because of missing data on certain measures.

0 = female, 1 = male; means represent proportion of males.

0 = Caucasian, 1 = African American; means represent proportion of African Americans.

0 = no drug use, 1 = some drug use; means represent proportion of parents who abused drugs.

Demographics

The five demographic variables (age, gender, race, SES, and site) were used to predict substance use in a logistic regression model, which is summarized in Table II. The overall model fit was significant, χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005, and univariate standardized βs indicated that being male, Odds Ratio (OR) = 2.04, p < .02, and being African American (OR = 2.64, p < .02) increased risk. The set of demographic variables was entered as the first step in all subsequent analyses.

Table II.

Predicting Initiation of Substance Use by the Sixth Grade From Demographic Variables

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1a | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

Note. Because of the varying sample sizes between models, all χ2 change figures were calculated by estimating the differences between omnibus model χ2s using the smallest possible sample size.

0 = Durham, 1 = Nashville, 2 = Washington, 3 = Pennsylvania; site was analyzed as a categorical variable with three degrees of freedom.

Home and Neighborhood Environment

The first hierarchical logistic regression tested the incremental utility of the two environmental factors in predicting early onset of substance use (see Table III). The omnibus fit of this model was significant, χ2(9, N = 283) = 19.98, p < .02; however, the addition of the environment variables did not make a significant contribution to the variance associated with early-onset substance use after the demographic variables had been entered, χ2 change (2, N = 283) = 0.16, p = ns. Thus, the effects of home and neighborhood environment on early-onset substance use are accounted for entirely by demographic factors.

Table III.

Model 1: Predicting Drug Use by the Sixth Grade From Kindergarten Environmental Variables

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1 | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

| 2. | Home environment | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.83–1.14 | .70 |

| Neighborhood environment | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.84–1.17 | .92 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(9, N = 283) = 19.98, p < .02; χ2 change = .16, p < .95 | |||||

Parenting Practices and Parent Mental Health History

The second hierarchical logistic regression tested the unique effects of parenting factors on early onset of child substance use (see Table IV). After adding the standard set of five covariates, six parenting variables were added to the model: parental warmth, physical punishment, verbal reasoning, parental involvement in school, maternal depression and parent substance abuse. The omnibus model fit with all 13 variables was highly significant, χ2(13, N = 250) = 52.76, p < .0001, and the addition of this set of variables significantly contributed to the variance associated with early-onset substance use, χ2 change (6, N = 250) = 24.41, p < .001. Increased verbal reasoning was significantly related to a decreased likelihood of substance use initiation by the sixth grade, Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.09, p < .01. Parental abuse of substances when children were in kindergarten was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of child substance use by the sixth grade (OR = 2.49, p < .02). In contrast, the unique relations between parental involvement in the kindergarten classroom and early initiation of substance use as well as maternal depression and early initiation of substance use were only marginally significant (OR = 0.54, p < .06; OR=1.03,p < .08, respectively). These findings suggest that children with involved parents may be less likely to engage in early onset substance use and those of depressed mothers may be more likely to engage in early-onset substance use, but replication studies with larger sample sizes are needed in order to determine the reliability of these effects. The other two parenting variables, parental warmth and physical punishment, were not significantly related to early onset of substance use after controlling for the other factors.

Table IV.

Model 2: Predicting Drug Use by the Sixth Grade From Kindergarten Parenting Variables

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1 | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

| 2. | Parental warmth | 0.04 | 1.12 | 0.66–1.88 | .68 |

| Physical punishment | 0.11 | 1.18 | 0.90–1.54 | .24 | |

| Verbal reasoning | −0.31 | 0.09 | 0.02–0.55 | .01 | |

| Parental involvement | −0.21 | 0.54 | 0.29–1.03 | .06 | |

| Maternal depression | 0.17 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | .09 | |

| Parent drug use | 0.21 | 2.49 | 1.16–5.32 | .02 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(13, N = 250) = 52.76, p < .0001; χ2 change = 24.41, p < .001 | |||||

Child Psychological and Behavioral Functioning

The third hierarchical logistic regression tested the unique effects of child psychological and behavioral factors on early onset of child substance use (see Table V). After the five covariates were added, four variables were included in the model: child IQ, inattention, overactivity, and history of medication for ADHD. The omnibus model fit was significant, χ2(11, N = 248) = 40.43, p < .0001, and the addition of these variables significantly contributed to the variance associated with early initiation of substance use, χ2 change (4, N = 247) = 11.86, p < .025. Analyses indicated that children who were higher on measures of overactivity in kindergarten were more likely to have initiated substance use by the sixth grade (OR = 1.16, p < .03). The other three child characteristic variables, IQ, inattention, and medication history did not add significantly to the prediction of early initiation of substance use.

Table V.

Model 3: Predicting Drug Use by the Sixth Grade From Kindergarten Child Psychological and Behavioral Variables

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1 | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

| 2. | Child IQ | 0.08 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | .53 |

| Inattention | −0.04 | 0.98 | 0.89–1.08 | .72 | |

| Overactivity | 0.26 | 1.16 | 1.01–1.33 | .03 | |

| Medication for ADHD | 0.14 | 1.55 | 0.92–2.62 | .10 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(11, N = 248) = 40.43, p < .0001; χ2 change =11.86, p < .025 | |||||

| 3. | Oppositional behavior | 0.05 | 1.67 | 0.21–12.76 | .62 |

| Aggressive behavior | 0.21 | 1.03 | 0.98–1.09 | .25 | |

| Delinquent behavior | −0.05 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | .75 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(14, N = 248)= 41.15, p < .001; χ2 change = .75, p < .90 | |||||

| 4. | Somatic complaints | 0.16 | 1.20 | 0.96–1.49 | .10 |

| Thought problems | 0.20 | 1.36 | 0.99–1.89 | .07 | |

| Withdrawn | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.32 | .77 | |

| Anxious/depressed | −0.31 | 0.84 | 0.71–0.98 | .03 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(18, N = 247) = 50.27, p < .0001; χ2 change = 9.04, p < .10 | |||||

At the third step, three externalizing variables were added to the model: oppositional behavior, aggressive behavior, and delinquent behavior. The addition of this set of variables was not significant. At the fourth step, four internalizing variables were added to the model: somatic complaints, thought problems, withdrawal, and anxiety/depression. The omnibus model fit was significant, χ2(18, N = 247) = 50.27,p < .0001,and the increment of these variables was marginally significant, χ2 change (4, N = 247) = 9.04, p < .10. There was a marginally significant effect of thought problems on early-onset substance use such that children identified in kindergarten as having more thought problems may have a greater likelihood of initiating substance use by the sixth grade (OR = 1.36, p < .07). Interestingly, the unique relation between kindergarten anxiety/depression and initiation of substance use was significant and negative (OR = 0.84, p < .03), indicating that children with higher levels of anxiety/depression in kindergarten were at decreased risk of using substances by the sixth grade. The other two internalizing variables, somatic complaints and withdrawal, were not significantly associated with initiation of substance use. The model was reestimated with the reverse order of entry and no significant differences emerged.

Child Social Functioning

The fourth hierarchical logistic regression tested the effects of children's social skills and adjustment on early initiation of substance use (see Table VI). After the five covariates were added, three social cognitive variables were added to the model: emotion recognition, hostile attributions, and social problem solving. The omnibus model fit was significant, χ2(10, N = 291) = 27.23, p < .002, and the addition of these variables significantly contributed to the variance associated with early initiation of substance use, χ2 change (3, N = 252) = 7.97, p < .05. Analyses indicated that children who had greater social problem solving skills in kindergarten were less likely to have used substances by the sixth grade (OR = 0.22, p < .04). The other two social cognitive variables, emotion recognition and hostile attributions, were not uniquely related to initiation of substance use. In the final step, two sociometric measures were added to the model: social preference score and prosocial nominations. The addition of this set of variables was not significant. The model was reestimated with the reverse order of entry and no significant differences emerged.

Table VI.

Model 4: Predicting Drug Use by the Sixth Grade From Kindergarten Social Functioning Variables

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1 | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

| 2. | Emotion recognition | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.97–1.24 | .16 |

| Hostile attributions | 0.10 | 1.90 | 0.60–6.24 | .28 | |

| Social problem solving | −0.18 | 0.22 | 0.05–0.93 | .04 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(10, N = 291) = 27.23, p < .002; χ2 change = 7.97, p < .05 | |||||

| 3. | Social preference | −0.03 | 0.96 | 0.61–1.51 | .84 |

| Prosocial nomination | −0.23 | 0.67 | 0.39–1.10 | .12 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(12, N = 252) = 33.48, p < .001; χ2 change = 4.31, p < .25 | |||||

Comprehensive Model

The final hierarchical logistic regression included the set of five covariates as the first step and the seven predictors achieving a p-value of .07 or less in the previous analyses (parental involvement in school, parental substance abuse, parental verbal reasoning, overactivity, thought problems, anxiety/depression, and social problem solving) as the second step (see Table VII). Although the identification of these predictors is data-driven, this provides a rigorous test of the unique relations among each predictor while controlling for all other predictors. The omnibus model fit was significant, χ2(14, N = 249) = 67.06, p < .0001. A significant proportion of the variance associated with early initiation of substance use was explained by the increment of the second set of variables, χ2 change (7, N = 249) = 38.06, p < .0001. Unique increments in the prediction came from higher levels of overactivity (OR = 1.14, p < .02), more thought problems (1.53, p < .01), parental substance abuse (OR = 2.82, p < .01), lower levels of parental verbal reasoning (OR = 0.11, p < .02), and greater social problem-solving skills deficits (OR = 0.18, p < .04). The unique relation between parental involvement in the kindergarten classroom and initiation of substance use was negative and marginally significant (OR = 0.56, p < .09). Anxiety/depression did not add significantly to the prediction of substance use.

Table VII.

Model 5: Final Comprehensive Model

| Step | Variable | Standardized β | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.56–1.97 | .85 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 2.04 | 1.14–3.72 | .02 | |

| Race | 0.27 | 2.64 | 1.21–5.88 | .02 | |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .38 | |

| Site 0 vs. 1 | 0.18 | 1.56 | 0.95–2.55 | .08 | |

| Site 0 vs. 2 | −0.02 | 0.94 | 0.51–1.66 | .84 | |

| Site 0 vs. 3 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.12 | .78 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(7, N = 295) = 20.53, p < .005 | |||||

| 2. | Parental involvement | −0.20 | 0.56 | 0.29–1.10 | .09 |

| Parent drug use | 0.23 | 2.82 | 1.28–6.23 | .01 | |

| Verbal reasoning | −0.28 | 0.11 | 0.02–0.73 | .02 | |

| Overactivity | 0.23 | 1.14 | 1.02–1.28 | .02 | |

| Thought problems | 0.28 | 1.53 | 1.10–2.11 | .01 | |

| Anxiety/depression | −0.16 | 0.91 | 0.79–1.05 | .18 | |

| Social problem solving | −0.21 | 0.18 | 0.03–0.95 | .04 | |

| Omnibus model χ2(14, N = 249) = 67.06, p < .0001; χ2 change = 38.06, p < .0001 | |||||

Incremental Risk Model

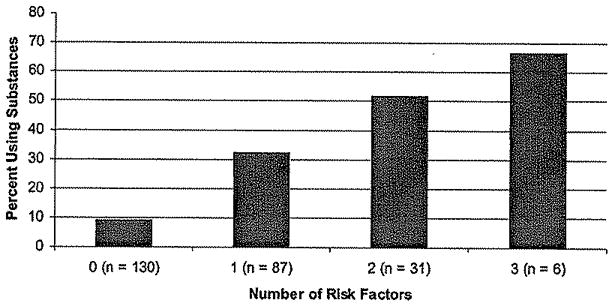

The regression analyses described above suggest that certain risk factors provide unique information in predicting early-onset substance use. Another way of depicting this phenomenon is to evaluate the relation between the number of risk factors that a child has and the likelihood of substance use. Each child was coded as having (or not having) each of the following five risk factors: (1) a substance-abusing parent; (2) a parent who failed to utilize verbal reasoning, defined as a score less than one standard deviation below the sample mean; (3) overactivity, defined as a score greater than one standard deviation above the sample mean; (4) thought problems, defined as a score greater than one standard deviation above the sample mean; and (5) social problem solving skills deficits, defined as a score less than one standard deviation below the sample mean. Figure 1 depicts the relation that was found between the number of risk factors and the likelihood of substance use. Specifically, children displaying two or more risk factors had at least a 50% chance of early-onset substance use and were approximately five times more likely to show early-onset substance use than were children with no risk factors, χ2(N = 254) = 38.08, p < .0001.

Fig. 1.

Early-onset substance use by number of risk factors. N = 254; risk factors include overactivity, thought problems, social problem-solving skills deficits, parental substance abuse, and lack of parental verbal reasoning. No children in the sample had more than 3 risk factors.

Alternative Externalizing Model

Although certain variables were identified as predictors of early-onset substance use, it is possible that these variables actually predict early-onset conduct problems in general as opposed to substance use in particular. In order to test this possibility, the final comprehensive model was reestimated while controlling for the presence of concurrent externalizing symptoms in the sixth grade, measured by the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Costello, Edelbrock, & Costello, 1985), a structured clinical interview designed to assess DSM-IV psychiatric disorders and symptoms in children and adolescents aged 6–17 years. Children were administered the DISC in Grade 6 (Year 7), and a total externalizing symptom count was generated which includes most of the major externalizing behavior diagnoses contained in the DSM-IV (e.g., Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, ADHD, etc.). Even with the inclusion of the total DISC externalizing symptom count in the final model (OR = 1.16, p < .002), almost all of the same predictors (i.e., parental substance abuse, parental verbal reasoning, overactivity, and social problem solving skills) remained significant in the prediction of early-onset substance use, χ2 change (6, N = 249) = 44.28, p < .0001, with the exception of thought problems, which was marginally significant (OR = 1.29, p < .08). These findings indicate that this set of variables has predictive utility specific to early-onset substance use above and beyond the effects of concurrent externalizing symptoms in the sixth grade.

Discussion

This study offers a unique perspective on the etiology of early-onset substance use through several means including its longitudinal design, its wide range of predictor variables, the use of multiple informants, and the diversity of the sample with respect to gender, ethnicity, and geographic location. The results indicate that it is possible to predict which children are at greatest risk of early-onset substance use as early as age six. Based on theories of adolescent substance use (Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990; Hawkins & Weiss, 1985; Simons et al., 1988), it was hypothesized that the most significant predictors of early-onset substance use would be parenting and child functioning factors as opposed to more distal factors such as the neighborhood environment or social status. The results provide support for this hypothesis and extend existing theory by providing information about the causes of children's initial involvement with substances prior to adolescence. It is important to note that this is one of the first studies to examine factors associated with early substance use experimentation; however, this study does not provide information concerning children at risk for early substance abuse. Although there is evidence that early initiation of substances predicts early substance abuse (Jackson et al., 1997; Kandel, 1982), future studies will need to address whether the factors involved in the early onset of substance use are the same as those involved with early substance abuse.

Demographic Factors

Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Costello et al., 1999; Jackson et al., 1997), the results of this study indicate that boys are at greater risk for early substance use than are girls. It is noteworthy that previous research indicates that African Americans are at decreased risk for adolescent substance use compared with Caucasians (Bachman et al., 1991; Kilpatrick et al., 2000), whereas this study found that African American children are at increased risk for early-onset substance use. It may be that African American children are likely to begin experimentation with substances at an earlier age than children of other ethnic groups, but may be less likely to engage in substance use later in adolescence. Replication studies as well as research that follows this same sample of children into adolescence are needed to understand these differences more clearly.

Parenting Practices and Parent Mental Health History

The multistage social learning model asserts that adolescents are more likely to initiate substance use if parents display patterns of substance use (Simons et al., 1988). Consistent with this theory, as well as previous empirical research (Beman, 1995; Costello et al., 1999; Dobkin, Tremblay, & Sacchitelle, 1997; Kilpatrick et al., 2000), parental substance abuse was the single strongest predictor of early initiation of child substance use in this sample.

It is not clear whether this relation is due to parental modeling of substance abusing behaviors, ineffective parenting techniques such as reduced parental monitoring in substance abusing parents, genetic transmission of risk, or some combination of these factors (Patterson & Bank, 1989). However, consistent with the findings of Costello et al. (1999), maternal depression is not significantly related to early onset of child substance use when controlling for parent substance abuse. This seems to indicate that it may be the direct modeling of parental substance abuse, as opposed to parental unavailability, that plays the most influential role in children's acquisition of substance using behavior. Future research is needed to clarify the respective roles of these different forms of parental psychopathology in the initiation of child substance use.

Besides modeling of parent's behaviors, the multistage social learning model indicates that another major predictor of adolescents' initial experimentation with substances is a lack of parental supervision and discipline (Simons et al., 1988). The results of this study indicate that children who have parents that engage in more frequent verbal reasoning strategies are less likely to initiate the use of substances. Research has shown that adolescents will be more likely to engage in substance use when parents fail to effectively monitor, reward, and punish the behavior of their children (Baumrind, 1985; Patterson, 1982) and when parents do not provide clear rules in the home (Kaplan, Johnson, & Bailey, 1986). It is likely that greater use of verbal reasoning is associated with increased parental monitoring of the child as well as more frequent provisions of verbal rewards or punishments.

Surprisingly, physical discipline strategies and parental warmth during kindergarten are not predictive of early-onset substance use, whereas studies of adolescent substance use have found that these factors are predictive of adolescent-onset substance use (Andrews, Hops, Ary, Tildesley, & Harris, 1993; Barnes & Windle, 1987; Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991). The lack of significant findings could be due to the measures that were used to assess these constructs. Parental warmth was derived from a parent self-report measure of parent–child interactions, which may be associated with reporting biases. The use of physical discipline strategies was assessed by the interviewer during an 18-min parent-child interaction task, which may not provide interviewers with enough information to make a reliable assessment of the parent's typical behavior toward the child. Additionally, it is likely that parents who are being observed may intentionally avoid using physical discipline practices in front of the interviewer. Future studies are needed in order to clarify the predictive utility of various parenting practices.

Child Psychological and Behavioral Functioning

In addition to parenting factors, children's psychological and behavioral functioning appear to be important in predicting early-onset substance use. Children who have higher levels of overactivity in kindergarten are more likely to begin using substances at an early age. This finding is consistent with research that has identified temperamental traits such as impulsivity and novelty-seeking behavior to be consistent predictors of early-onset substance use (Masse & Tremblay, 1997) as well as adolescent-onset substance use (Newcomb & Earlywine, 1996; Windle & Windle, 1993). Interestingly, neither inattention nor medication for ADHD are predictive of early-onset substance use once overactivity is taken into account. A recent study by Molina, Smith, and Pelham (1999) also found that dimensionally scored impulsivity-hyperactivity symptoms, but not symptoms of inattention, accounted for substance use in adolescents.

Previous studies of adolescents have noted a positive relation between problem behaviors and adolescent substance use (e.g., Brooke, Whiteman, & Finch, 1992; Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & White, 1999; White, Brick, & Hansell, 1993); however, the current study found a nonsignificant association between these behaviors and early-onset substance use once overactivity was taken into account. It may be that it is not problem behaviors in and of themselves that cause adolescents to initiate substance use, but their resulting association with deviant peers that leads them to begin experimentation with substances (Simons et al., 1988). Because the multistage social learning model also asserts that adolescents will gravitate toward substance using peers if they themselves have used substances in the past, further research is needed to understand the temporal relation between deviant peer affiliation and substance use.

Children who display more thought problems in kindergarten are also at greater risk of early-onset substance use; however, this finding should be interpreted with caution. The mean for the thought problems scale is only 1.22 for the substance using group, which indicates that the average score for this group is barely higher than “somewhat true” on any one item. In addition, the thought problems scale appears to be highly correlated with externalizing symptoms such as overactivity, aggression, and delinquent behavior. Therefore, it is difficult to know exactly what the thought problems scale is measuring. Despite these caveats, it may be that children who are rated higher on thought problems are more likely to associate with deviant peers, given their own deviant thought processes, which is likely to lead to early experimentation with substances. However, more research is needed to understand the mediating mechanism in the relation between thought problems and early-onset substance use.

The multistage social learning model asserts that adolescents will escalate in their substance use when they are emotionally distressed in an effort to relieve their anxiety or depressive symptoms (Simons et al., 1988). Although the relation between anxiety/depression and initiation of substance use in this study is nonsignificant in the final, comprehensive model, anxiety/depression is significantly and negatively related to early-onset substance use in the third model. This is consistent with recent research that found certain forms of internalizing symptoms to be inversely related to initiation of alcohol use (Kaplow et al., 2001) and initiation of cigarette use (Costello et al., 1999). It may be that children who experience internalizing symptoms in the absence of externalizing symptoms are more behaviorally inhibited and tend to avoid novel stimuli/situations such as experimentation with substances. It remains to be seen whether these children will eventually turn to substances as a means of coping with their emotional distress later in their development. Future studies are needed to better understand the effects of different forms of internalizing problems on substance use over time.

Child Social Functioning

The multistage social learning model proposes that greater social skills may prevent children from initiating substance use at an early age by providing more adaptive strategies for dealing with social distress or problematic situations with peers (Simons et al., 1988). This study found that greater social problem solving skills in kindergarten are related to a decreased risk of early-onset substance use. This is consistent with research that has found social impairment in childhood to be a critical predictor for later substance use disorders (Greene et al., 1999).

In contrast to social problem solving skills, sociometric ratings such as peer nominations for social acceptance or engaging in prosocial behavior in the first grade are not significantly associated with early-onset substance use. Because children are not usually exposed to substances in a social context prior to adolescence (Oetting & Beauvais, 1987), peer status may not play a role in the initiation of substance use until later in development. On the other hand, it is possible that peer status measured closer to the time of substance use initiation (i.e., in the 4th grade) may indeed predict early-onset of substance use. Children who are lacking in prosocial behavior are likely to be rejected by their peers and will tend to gravitate toward other rejected children (Dodge, 1983), who in turn, promote substance abuse and involvement in antisocial activities (Elliot, Ageton, & Huizinga, 1985; Keenan, Loeber, Zhang, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1995). Sufficient evidence has accumulated over the years indicating that, at some point during development, the affiliation with deviant peers becomes strongly associated with substance-using behaviors (e.g., Clark, Parker, & Lynch, 1999; Jessor, Chase, & Donovan, 1980; Kandel, 1978; Kaplan, Martin, & Robbins, 1984; Oetting & Beauvais, 1987). However, future research is needed in order to determine the age, or developmental period, at which children's peer group status begins to play a more influential role in the initiation of substance use.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study must be noted. First, this study relied upon child self-report measures of alcohol and drug use by the sixth grade, which may be associated with underreporting. At the same time, the measure assessing alcohol use does not discriminate between alcohol use without parental permission versus alcohol use under parental supervision (e.g., religious ceremonies). Future studies that are able to differentiate unsanctioned alcohol use and alcohol use under parental permission are needed. In addition, the 24% attrition rate may have biased our sample, although attrition analyses revealed no evidence of bias with respect to the available data.

This study focused only upon initiation of early-onset substance use. Future research that examines the etiology of other stages of early substance use such as regular use, escalations in use, and substance abuse is needed. In addition, the potential moderating effects of certain demographic characteristics such as gender and race, as well as potential mediating mechanisms should be examined in future studies.

Conclusions and Implications

The results of this study expand upon existing theory and empirical work by examining predictors of substance use initiation in preadolescent children. The results of this study suggest a typology of substance users in childhood that differentiates preadolescent substance users from adolescent-onset substance users. The former group may be characterized by a form of psychopathology related to parenting behaviors (e.g., substance abuse and disciplinary practices) and child temperament, and the latter group may be more socially influenced by neighborhood and peer culture. A similar typology has proven useful in conduct disorder research (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992; Moffitt, 1993; Patterson & Bank, 1989).

These findings have important implications for the prevention of early-onset substance use. A screening device that includes measures of parental substance abuse, parental verbal reasoning, child overactivity, thought problems and social problem solving skills during kindergarten can identify a group of children who have at least a 50% chance of initiating substance use before age 12. Given that early-onset substance use is likely to grow into costly outcomes during adolescence, this high sensitivity means that intensive prevention efforts can be focused on this high-risk group in a way that could prove more cost-beneficial than universal interventions that are less focused. Furthermore, examination of the nature of the risk factors provides clues about the potential targets of preventive interventions at different stages of development.

Intervention programs are likely to be most effective if they target a high-risk group, are developmentally sensitive, and are comprehensive (Williams, Perry, Farbakhsh, & Veblen-Mortenson, 1999). The multistage social learning model asserts that early initiation of substance use is likely when a child's parents model regular substance use and when parents utilize ineffective parenting techniques (Simons et al., 1988). Additionally, children tend to emulate parents' methods of social and emotional coping, and if parents use substances as a coping strategy, children are likely to do so as well (Simons et al., 1988). This model is consistent with our findings regarding the important influence of parent substance abuse, parental verbal reasoning, and children's social problem solving skills. Consequently, programs aimed at reducing early-onset substance use in particular may be most beneficial if parenting behaviors as well as children's social coping strategies are included as major targets of intervention.

The identification of age-specific predictors of substance use is critical for informing preventive intervention efforts at different developmental stages. Follow-up studies involving the current sample will greatly help with this endeavor by assessing children beyond the sixth grade, further differentiating predictors of early versus later onset of substance use, and determining the conditions under which these effects hold.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants R18MH48043, R18MH50951, R18MH50952, R18MH50953, K05MH00797, K05MH01027, and DA13148. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention also has provided support through a memorandum of agreement with NIMH. Support has also come from the Department of Education Grant S184U30002 and the NC Governor's Institute on Alcohol and Substance Abuse Scholars Program. We are grateful for the collaborations with Durham Public Schools, the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, the Bellefonte Area Schools, the Tyrone Area Schools, the Mifflin County Schools, the Highline Public Schools, and the Seattle Public Schools. We greatly appreciate the hard work and dedication of the many staff members involved with the Fast Track project.

Footnotes

An alternative analytic strategy would be to use survival analysis; however, we decided against this strategy because of the small number of repeated measures as well as the low new incidence rate of substance use at each time point.

Correlation matrices among all continuous predictor variables are available for downloading from the following website: www.unc.edu/∼curran.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary DV, Tildesley E, Harris J. Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wallace JM, Jr, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976–1989. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention. In: Tramontana M, Hooper S, editors. Assessment issues in child clinical neuropsychology. New York: Plenum; 1988. p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, McMurray MB, Edelbrock CS, Robbins K. The response of aggressive and nonaggressive ADHD children to two doses of methylphenidate. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:873–881. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Windle M. Family factors in adolescent alcohol and drug abuse. Pediatrician. 1987;14:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Familial antecedents of adolescent drug use: A developmental perspective. In: Jones CL, Battjes RJ, editors. Etiology of drug abuse: Implications for prevention. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Beman DS. Risk factors leading to adolescent substance abuse. Adolescence. 1995;30:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch S. Childhood aggression, adolescent delinquency, and drug use: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1992;153:369–383. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1992.10753733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: A longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Psychopathology as a risk for adolescent substance use disorders: A developmental psychopathology prespective. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(3):355–365. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Parker AM, Lynch KG. Psychopathology and substance-related problems during early adolescence: A survival analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:333–341. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, et al. The science of prevention: A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorder: The Fast Track Program. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Technical reports for the Fast Track assessment battery. 1999. Unpublished technical reports. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Social control and social learning models of delinquent behavior. Criminology. 1976;14:17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Costello AJ. Validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children: A comparison between psychiatric and pediatric referrals. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1985;13:579–595. doi: 10.1007/BF00923143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]