Abstract

Introduction: Reduction of ovarian estrogen secretion at menopause increases net bone resorption and leads to bone loss. Isoflavones have been reported to protect bone from estrogen deficiency, but their modest effects on bone resorption have been difficult to measure with traditional analytical methods.

Methods: In this randomized-order, crossover, blinded trial in 11 healthy postmenopausal women, we compared four commercial sources of isoflavones from soy cotyledon, soy germ, kudzu, and red clover and a positive control of oral 1 mg estradiol combined with 2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone or 5 mg/d oral risedronate (Actonel®) for their antiresorptive effects on bone using novel 41Ca methodology.

Results: Risedronate and estrogen plus progesterone decreased net bone resorption measured by urinary 41Ca by 22 and 24%, respectively (P < 0.0001). Despite serum isoflavone profiles indicating bioavailability of the phytoestrogens, only soy isoflavones from the cotyledon and germ significantly decreased net bone resorption by 9% (P = 0.0002) and 5% (P = 0.03), respectively. Calcium absorption and biochemical markers of bone turnover were not influenced by interventions.

Conclusions: Dietary supplements containing genistein-like isoflavones demonstrated a significant but modest ability to suppress net bone resorption in postmenopausal women at the doses supplied in this study over a 50-d intervention period.

Commercial phytoestogen supplement preparations have modest ability to reduce bone resorption in postmenopausal women compared to traditional therapies.

Chronically high rates of bone resorption relative to bone formation that occur with menopause and aging lead to bone loss and, ultimately, to osteoporosis. Estrogen hormone replacement therapy suppresses bone resorption and reduces fracture incidence in postmenopausal women (1,2). However, adverse health risks, including stroke, embolism, and breast cancer identified in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (2), have stimulated a search for alternative nonhormonal antiresorptive agents for prevention of bone loss. Bisphosphonates fit this requirement and are medically prescribed for the prevention of bone loss and fracture in patients with, or at risk of, osteoporosis (1). Although relatively well tolerated, side effects include hypocalcemia, skin rashes, esophageal ulceration, and in some cases osteonecrosis of the jaw in the immunosuppressed (3). Isoflavones, natural plant compounds recognized for their estrogen-like effects, are commercially available without prescription and are used as an alternative to estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women without compelling evidence for their efficacy (4). The major commercial sources of isoflavones used in botanical dietary supplements marketed for this purpose are derived from soybeans, red clover, and kudzu (5). They are assumed to have a more favorable safety profile than estrogen because of their higher relative binding affinity for estrogen receptor-β in bone than for estrogen receptor-α, which is abundant in reproductive tissues (5), although plasma concentrations after ingestion of modest amounts (∼50 mg/d) of isoflavones may exceed levels of endogenous estradiol by several orders of magnitude (50–80 ng/ml vs. 40–80 pg/ml) (6). Soy food consumption has been shown to be associated with decreased risk of fracture in a sample of more than 24,000 postmenopausal women studied over 4 yr in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (7).

Commercial isoflavone supplements vary in their source and consequently in their isoflavone profiles and potencies. A comparison of the antiresorptive effect on bone of isoflavones from different sources with each other and with estrogen and bisphosphonates has not been evaluated because of the large sample size required with the current measures of bone resorption. Such a comparison has recently become practical in a small sample size using a novel sensitive screening technique using 41Ca that rapidly responds to effective interventions on bone resorption (8). The evidence for an effect of estrogen and phytoestrogens on other parameters of mineral transport including calcium absorption is unclear (5).

The aims of this study were 2-fold. The first was to compare plant-derived isoflavones from various commercial sources with effective antiresorptive drug therapies for their ability to suppress bone resorption and alter calcium absorption in postmenopausal women. The second was to compare the effects on net bone resorption measured by 41Ca methodology with those measured by standard biochemical markers of bone resorption in blood and urine.

Subjects and Methods

Study participants

Twelve healthy postmenopausal women were enrolled in the study, 11 of whom completed the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after approval of the study by Purdue University and Indiana University Purdue University Institutional Review Boards.

Seven subjects had been dosed with 41Ca from a previous study (8) and five subjects had not. Exclusion criteria included less than 4 yr postmenopausal; use of estrogen hormone replacement therapy, antiresorptive drugs, and drugs for the treatment of bone disease; thiazide diuretics; thyroid replacement therapy; corticosteroids; nonprescription drugs; isoflavone consumption; and a history of malabsorptive, bone, liver, kidney, hormonal, cancer disease, or soy allergies. No racial groups were excluded. One Asian woman dropped out after being diagnosed with hemochromatosis. The remaining 11 white women completed all phytoestrogen phases. Subjects were initially offered estradiol plus medroxyprogesterone as the positive control, but after publicity surrounding the premature termination of the Women’s Health Initiative hormone trial, a bisphosphonate was offered instead. Six women opted for the bisphosphonate as a positive control and one woman declined any positive control (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through study.

Serum FSH and LH were measured at screening to verify postmenopausal status, and biochemical variables were measured to determine the health of the subjects. Areal bone mineral content and bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, proximal femur, and total body were measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DPX IQ; Lunar, Madison, WI) at the beginning of the study.

Study design

The study design was a blinded, randomized order, crossover intervention trial. The plan was to compare the effect of four commercial isoflavone supplements with oral hormone replacement therapy or an oral bisphosphonate on bone resorption and calcium absorption in postmenopausal women who did not actively supplement with isoflavones.

All subjects received four plant-derived commercially available botanical supplements derived from soy cotyledon, soy germ, red clover, or kudzu (Table 1). The isoflavone profile of each supplement varied with the botanical source and the dose varied with manufacturer recommendations. Subjects were asked to take each intervention in divided doses throughout the day with meals but to consume all capsules/tablets by midnight. They were advised not to take extra pills on any day to compensate for previously missed pills. Either 1 mg oral estradiol (Estrace) combined with 2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone (Provera®, Parmacia & Upjohn Company, Division of Pfizer Inc., New York, NY) daily or 5 mg/d of risedronate (Actonel®, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, OH) was used as the positive control for comparison. Participants were instructed to take risedronate on rising at least 30 min before consuming food or beverages and to take estrogen before breakfast.

Table 1.

Commercial botanical supplement interventionsa

| Plant source brand (manufacturer) | Soy cotelydon Prevastein (Cognis) | Soy germ Soylife EXTRA (Acatris) | Red clover Rimostil (Novagen) | Kudzu Kudzu (Nature’s Plus) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. capsules or tablets/d | 7 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| Composition, mg (aglycones)/daily dose | ||||

| Daidzin | 55.37 | 49.42 | 0 | 21.60 |

| Glycitin | 0 | 70.35 | 0 | 0 |

| Genistin | 158.55 | 17.15 | 0 | 0.96 |

| Daidzein | 3.08 | 11.83 | 1.75 | 2.04 |

| Glycitein | 0 | 2.77 | 0.102 | 0.68 |

| Genistein | 2.67 | 1.23 | 0.562 | 0 |

| Puerarin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 143 |

| Formononetin | 0 | 0 | 31.10 | 0 |

| Biochanin A | 0 | 0 | 6.40 | 0 |

| Total | 220 | 153 | 40 | 168 |

Analysis was by HPLC done by Silliker, Inc. (Orem, UT). Internal HPLC analysis using higher solvent to product ratios showed total isoflavone intake of 699 mg/d for soy cotyledon, 435 mg/d for soy germ, 251 mg/d for red clover, and 674 mg/d for kudzu.

Mean of duplicate analysis of 10 capsules/tablets per intervention by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists method (7).

The randomization schedule for order of intervention was determined by the statistician. Although subjects were not told which intervention they were on, the intervention regimen varied and tablets and capsules varied in number per day and appearance. Subjects were provided 500 mg/d calcium (Viactive; McNeil Nutritionals, LLC, Ft. Washington, PA) and 500 IU/d vitamin D3 (100 IU/d from the Viactive plus an additional 400 IU/d from Rexall Sundown, Inc., Boca Raton, FL) throughout the study beginning at baseline to minimize fluctuations in calcium intake and vitamin D status. The subjects completed a 3-d food record before and during each intervention period to assess their usual dietary pattern. Nutrient intakes were calculated by using the Nutrition Data System for Research (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) (version v4.04/32). Adverse events were monitored before and during each intervention period by interview.

Biochemistries

Fasting blood and urine samples were obtained at the beginning and end of each intervention period for the measurement of serum isoflavone concentrations and biochemical markers of bone turnover. Serum isoflavone concentrations were used as an indicator of compliance. Serum isoflavone concentrations were analyzed as previously described (9,10) using reverse-phase HPLC-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry using a PE-Sciex API III triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex, Concord, Canada). Biochemical markers of bone turnover included urinary collagen type I cross-linked N teleopeptides, urinary free deoxypyridinoline, and serum bone alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin. In addition, serum PTH, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, and 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D were measured at the end of each intervention. RIAs, immunoradiometric assays, and enzyme immunoassays were used to measure hormones and biochemical markers of bone turnover. The interassay percent coefficient of variation (CV) for urinary N-telopeptide cross-links is 7.1 and 12.6% for serum PTH. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (10.5% CV) and 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D (10.5% CV) were measured by using RIAs (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN). Serum osteocalcin was measured (9% CV) using a RIA that was developed at the Indiana University General Clinical Research Center.

41Ca technique

Subjects were given 41Ca (Argonne National Laboratories, Argonne, IL) by iv injection in sterile saline. Subjects enrolled in the previous study (8) received 100 nCi or 1 μCi, and newly enrolled subjects received 50 nCi after it was determined that this dose was sufficient to be detected. A period of 100 d or more was allowed to clear 41Ca from soft tissues and establish equilibrium between 41Ca released from bone by resorption and 41Ca excreted in urine. Baseline measures of urinary 41Ca were collected over the subsequent 100 d. An intervention period of 50 d was selected because the response of urinary 41Ca to a bisphosphonate has been shown to be complete by 50 d (11). Each 50-d intervention period was preceded by a preintervention period of 50 d or more that served as the baseline period of 41Ca excretion for the next intervention period. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected approximately every 10 d during all pre- and intervention periods for the measurement of 41Ca by accelerator mass spectrometry as previously described (8).

Calcium absorption

At the end of baseline and each intervention period, a calcium absorption test with 15.2 mg 44Ca as CaCO3 and the assigned supplement as part of a test meal containing 250 mg Ca was performed as previously described (8). 44Ca enrichment was determined in the 5-h blood sample by Inductively Coupled Plasma and Mass Spectrometry as previously described (12). Fractional calcium absorption was determined as: (5-h SSA0.92373) × [0.3537 × (height [meters]0.52847) × (weight [kilograms]0.37213)] where SSA = serum-specific activity (fraction dose per gram Ca) (13).

Statistical analysis and sample size calculation

Means and sds of subject characteristics and outcome measures were determined. Biochemical measures of responses to interventions were compared using ANOVA. The natural logarithm of the urinary 41Ca to Ca ratio was analyzed using a modified general linear model described previously in an online appendix (8). The model includes terms for subject, time, the subject-by-time interaction, and intervention period. It allows for the intervention effects to be estimated as contrasts between the intervention period and the corresponding preintervention (control) period. Exponentiating these differences expresses the treatment effect as the relative resorption (RR). A value of RR = 1.0 corresponds to no change in net bone resorption reduction, whereas RR = 0.8 corresponds to a 20% reduction in bone resorption. ses for significance tests were calculated using asymptotic methods and the bootstrap procedure (14). The statistical model and the bootstrap procedure with SAS programs SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and sample data are available (http://www.stat.purdue.edu/∼mccabe/ca41/). For a sample of size of 10, the power of detecting a RR of 0.94, i.e. a 6% reduction in resorption, is 80%. This high power is a consequence of the crossover design in which subjects are used as their own controls.

Linear models were used to test the ability of subject characteristics, serum isoflavone levels, and biochemical measurements to predict the response in RR. SAS software (version 9.0; SAS Institute) was used for all computations.

Results

Baseline characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the participants and study average nutrient intakes

| Characteristics | Mean ± sd (minimum, maximum) (n = 11) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 59.8 ± 4.7 (52, 65) |

| Height, m | 1.61 ± 0.05 (1.5, 1.7) |

| Weight, kg | 79.2 ± 8.5 (65.1, 88.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.6 ± 3.6 (24.5, 35.4) |

| Time after menopause, yr | 11.25 ± 0.5 (6, 24) |

| Total body bone mineral density, g/cm2 | 1.13 ± 0.10 (0.98, 1.28) |

| Total body bone mineral content, g | 2560 ± 468 (2037, 3489) |

| Dietary calcium, mg/d | 718 ± 232 (347, 992) |

| Dietary phosphorus, mg/d | 1032 ± 260 (260, 624) |

| Dietary magnesium, mg/d | 240 ± 62 (154, 346) |

| Serum FSH, mIU/ml | 50.9 ± 22.0 (27.4, 92.0) |

| Serum SHBG, nmol/liter | 170.5 ± 33.4 (130.7, 236) |

| Serum estrone, pg/ml | 31.4 ± 8.7 (18.3, 46.9) |

| Serum estrone sulfate, ng/ml | 0.38 ± 0.12 (0.2, 0.5) |

| Serum estradiol, pg/ml | 11.9 ± 2.8 (7.8, 17.5) |

| Fractional calcium absorption | 0.32 ± 0.22 (0.082, 0.62) |

At baseline, subjects were past the rapid bone loss phase associated with menopause. All women underwent natural menopause. Compared with non-Hispanic white women in the United States of similar age, subjects were similar in height and bone mineral density but were heavier. Average habitual calcium intake was below the 1200 mg/d recommended for this age group, but the supplement brought the mean intake to this level.

Subjects attended all clinic visits and completed all interventions except for one dropout and one woman who declined the positive control. To encourage compliance, the study pills were packaged in daily packets and supplied for 10-d periods. Subjects met with staff every 10 d. One subject experienced breakthrough bleeding in response to estrogen. One subject diagnosed with hemachromatosis discontinued the study. Two subjects reported gastrointestinal discomfort during the soy intervention. Serum isoflavone levels indicated good compliance with the interventions and variable bioavailability of the soy isoflavones (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biomarkers of bone turnover and calcium regulating hormones at baseline and at the end of each intervention

| Variable | Intervention, mean ± sd (minimum, maximum)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Estradiol/risedronate | Soy cotyledon | Soy germ | Red clover | Kudzu | P value | |

| Serum BAP, ng/ml | 15.8 ± 5.0 (9.6, 25.0) | 12.6 ± 5.9 (0.3, 23.3) | 14.6 ± 4.2 (9.1, 21.5) | 13.3 ± 7.3 (0.3, 23.0) | 12.6 ± 5.5 (0.3, 21.4) | 15.2 ± 6.9 (0.3, 25.5) | n.s. |

| Serum Alk Phos, U/liter | 82.4 ± 23.2a (42, 125) | 73.1 ± 22.8 (42, 115) | 78.9 ± 26.4 (43, 133) | 69.2 ± 27.5 (1, 94) | 59.1 ± 31.5b (3, 112) | 82.9 ± 24.7 (39, 127) | 0.0352 |

| Urinary NTx/Cr,nmol BCE/mmol creatinine | |||||||

| Fasting | 27.9 ± 14.8 (9.1, 54.4) | 20.5 ± 13.0 (5.6, 44.3) | 18.7 ± 10.4 (1.3, 34.1) | 28.4 ± 12.6 (6.7, 46.2) | 23.3 ± 9.2 (8.4, 33.7) | 30.7 ± 16.2 (9.0, 68.5) | n.s. |

| 24 h | 17.2 ± 9.9 (5.3, 39.5) | 13.5 ± 6.8 (2.9, 21.6) | 15.3 ± 7.2 (6.9, 30.0) | 17.4 ± 7.2 (4.9, 27.1) | 16.2 ± 6.5 (8.4, 31.3) | 20.6 ± 8.5 (4.9, 33.0) | n.s. |

| Urinary fDPD/Cr, nmol/mmol | |||||||

| Fasting | 6.1 ± 1.5 (4.1, 8.5) | 6.6 ± 2.6 (3.9, 12.5) | 5.3 ± 2.2 (0.6, 8.9) | 6.1 ± 1.8 (4.2, 10.0) | 5.9 ± 1.3 (4.5, 8.4) | 6.0 ± 1.6 (3.9, 9.5) | n.s. |

| 24 h | 4.7 ± 1.5 (2.8, 7.1) | 4.6 ± 1.2 (2.7, 7.0) | 4.4 ± 1.0 (3.3, 6.6) | 4.7 ± 1.3 (2.8, 7.2) | 5.2 ± 1.7 (2.5, 8.0) | 4.9 ± 0.9 (3.7, 6.7) | n.s. |

| Urinary calcium, mmol/24 h | 7.4 ± 3.1 (2.9, 14.3) | 8.1 ± 7.1 (2.1, 25.4) | 9.1 ± 7.9 (2.0, 26.3) | 8.9 ± 5.9 (1.3, 22.6) | 8.6 ± 4.6 (2.1, 14.7) | 9.7 ± 8.0 (3.5, 28.7) | n.s. |

| Urinary phosphorous, mmol/24 h | 40.2 ± 12.9 (23.0, 68.9) | 43.0 ± 28.1 (15.8, 114.2) | 55.3 ± 27.1 (30.0, 101.7) | 43.4 ± 19.5 (22.0, 71.1) | 41.8 ± 15.8 (22.7, 74.6) | 48.5 ± 27.2 (14.9, 99.2) | n.s. |

| Serum PTH, pg/ml | 40.0 ± 23.7 (15.8, 95.8) | 45.6 ± 17.5 (28.5, 78.5) | 41.5 ± 26.7 (10.7, 104.2) | 40.5 ± 20.6 (14.9, 82.4) | 43.9 ± 28.3 (11.5, 114.6) | 35.3 ± 26.2 (11.2, 102.4) | n.s. |

| Serum 25 (OH)D, ng/ml | 22.9 ± 6.5 (8.9, 31.9) | 24.4 ± 4.9 (18.5, 33.8) | 26.7 ± 4.4 (20, 32.7) | 24.2 ± 5.1 (17.6, 33.0) | 24.3 ± 5.0 (17.3, 35.2) | 25.9 ± 6.0 (19.3, 37.3 | n.s. |

| Serum equol n = 11 | 20.0 ± 43.5 (0.4, 142.5) | 4.6 ± 5.7a (0.2, 17.4) | 644 ± 1358 (0, 4445) | 1933 ± 3151b (0, 7845) | 1703 ± 2601b (1, 7605) | 5278 ± 12750b (0, 42100) | 0.0002 |

| Equol producers n = 5 | 38.2 ± 69.6 (2.1, 142.5) | 5.0 ± 7.4 (1, 17.4) | 1415 ± 1802 (7, 4445) | 2869 ± 3280 (341, 7585) | 3722 ± 2752 (915, 7605) | 11604 ± 17739 (619, 42100) | n.s. |

| Equol non producers n = 6 | 7.9 ± 8.2 (0, 20.7) | 4.2 ± 4.3 (1, 11.5) | 2 ± 1 (0, 4) | 1309 ± 3202 (0, 7845) | 21 ± 37 (1, 96) | 6 ± 5 (0, 15) | n.s. |

| Serum daidzein, nmol/liter | 65.6 ± 112.7a (0, 383) | 197.0 ± 577.4a (0, 1840) | 2425 ± 1990b (7, 5010) | 5663 ± 4489b (80, 13350) | 1066 ± 1178b (59, 3395) | 1809 ± 2091b (0, 6560) | <0.0001 |

| Serum DHD, nmol/liter | 45.5 ± 99.2a (0, 321) | 5.0 ± 6.8a (0, 21) | 776 ± 733b (4, 2190) | 1263 ± 970b (50, 2600) | 762 ± 903b (25, 2410) | 975 ± 1400b (0, 4570) | <0.0001 |

| Serum O-DMA, nmol/liter | 5.2 ± 8.6a (0, 26.5) | 2.2 ± 6.2a (0,19.6) | 999 ± 1009b (0, 2385) | 572 ± 535b (42, 1590) | 282 ± 382 (0,1165) | 366 ± 555 (0, 1765) | 0.0004 |

| Serum genistein, nmol/liter | 74 ± 52a (17, 185) | 126 ± 203a (15, 665) | 3489 ± 3172b (24.5, 10350) | 835 ± 694b (41, 2100) | 138 ± 214a (9, 761) | 101 ± 109a (19, 391) | <0.0001 |

| Serum total (aglycones) isoflavones, nmol/liter | 210 ± 294a (39, 1033) | 335 ± 573a (16, 1859) | 8333 ± 5740b (38, 16400) | 10266 ± 7930b (261, 25445) | 3951 ± 2802b (396, 8554) | 8529 ± 13510b (26, 45547) | <0.0001 |

Different letter superscripts within a row indicate mean group differences.

BAP, Bone alkaline phosphatase; Alk Phos, alkaline phosphatase; NTx, crosslinked N-telopeptides of type I collagen; Cr, creatinine; BCE, bone collagen equivalents; fDPD, free deoxypyridine; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; DHD, dehydrodaidzein; O-DMA, o-desmethylangolensin; n.s., not significant.

The participants’ food records showed no changes in nutritional composition of diets from baseline to end of study, and all records were averaged (Table 2). Subjects were low habitual consumers of soy products according to interview and diet records.

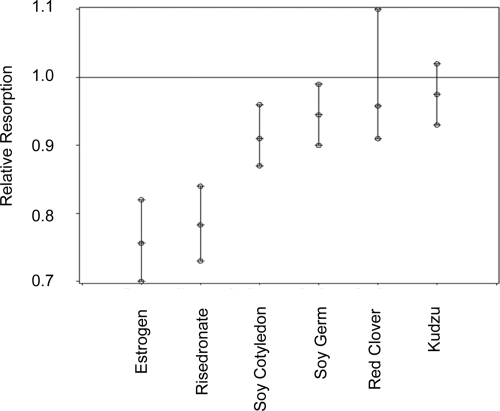

Net bone resorption (Fig. 2 and Table 4)

Figure 2.

Suppression of bone resorption (RR) by commercial isoflavone supplements and traditional pharmaceutical therapies, estradiol or risedronate. The line at RR = 1.0 is the preintervention comparison. The error bars indicate 95% confidence interval about the mean.

Table 4.

Estimated RR due to interventionsa

| Intervention | RR | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | 0.756 | 0.70–0.82 | <0.0001 |

| Risedronate | 0.783 | 0.73–0.84 | <0.0001 |

| Soy cotyledon | 0.910 | 0.87–0.96 | 0.0002 |

| Soy germ | 0.945 | 0.90–0.99 | 0.0312 |

| Red clover | 0.958 | 0.91–1.10 | 0.0928 |

| Kudzu | 0.975 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.3100 |

n = 11 except subjects either opted for estrogen (n = 4) or risedronate (n = 6) as a positive control.

RR was 0.756 (P < 0.0001) for estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone, indicating that bone resorption was suppressed by 24.4% compared with the preintervention period (Table 3). RR was 0.783 (P < 0.0001) for risedronate.

Supplements derived from soy cotyledon were the most effective plant-derived isoflavones, (RR 0.910, P < 0.001) but were only approximately one third as effective as estrogen therapy. Supplements derived from the soy germ (RR 0.945, P < 0.05) were half as effective as the soy cotyledon product. Neither the red clover nor the kudzu supplements significantly (P > 0.05) reduced bone resorption. When residual effects of the positive control interventions were apparent, i.e. urinary 41Ca did not return to baseline levels during the recovery period, in a few of the subjects, indicating a carry-over effect into the next recovery period, we removed data for all subsequent interventions and found that results were not altered. This primarily affected the kudzu phase, which was reduced to seven subjects when post positive control intervention periods were eliminated.

Calcium absorption

Fractional calcium absorption was not different between baseline and any intervention. The average fractional calcium absorption for baseline and all six interventions was 0.40 ± 0.26 (0.32 ± 0.22 for baseline, 0.58 ± 0.32 on estrogen, 0.52 ± 0.28 on risedronate, 0.33 ± 0.16 on soy cotyledon, 0.40 ± 0.24 on soy germ, 0.38 ± 0.20 on red clover, and 0.40 ± 0.23 on kudzu). It is possible that with a larger cohort (n = 36–52), estrogen and risedronate may have significantly enhanced calcium absorption.

Serum isoflavones and biochemistries (Table 3)

Serum PTH and 25(OH) vitamin D and urinary calcium and phosphorus were unaffected by intervention. Biochemical markers of bone turnover were also unaffected by the intervention with the exception that serum alkaline phosphatase was lower (P < 0.04) during the red clover intervention than at baseline.

Total serum isoflavone levels were much higher during intervention with dietary supplements. Total serum isoflavone levels were similar except for during the red clover intervention, reflecting the lower total isoflavone dose of that dietary botanical supplement. Serum genistein levels were highest during the soy cotyledon intervention, reflecting the higher dose of this isoflavone. Neither individual or total serum isoflavone levels or any biochemical marker explained the response to bone resorption due to intervention.

Discussion

In this randomized-order, crossover trial, we demonstrated that botanical dietary supplements derived from soy cotyledon and germ marketed to prevent postmenopausal bone loss did significantly suppress net bone resorption in postmenopausal women, but the magnitude of effect was modest compared with either hormone replacement therapy or the risedronate. Dietary supplements derived from soy red clover or kudzu did not significantly reduce bone resorption, even though they are marketed as natural, nonhormonal therapies with the potential to attenuate bone loss in postmenopausal women. This study sheds light on the mixed results of trials with phytoestrogens, some of which showed a positive effect on bone mass (15,16,17,18,19) and others that demonstrate no effects (20,21,22,23). Our ability to use a crossover design removed confounding factors associated with different cohorts and allowed a direct comparison of various profiles of plant-derived isoflavones.

The primary outcome measure we used was urinary excretion of 41Ca from prelabeled skeleton. 41Ca is a rare isotope with a long half-life of about 105 yr that can be analyzed by accelerator mass spectrometry at concentrations of 10−18 m. 41Ca enters the bone and once soft tissue clearance is complete, its appearance in the urine represents a stable marker of bone resorption that can be monitored for the rest of the person’s life. Multiple interventions can be compared in the same subjects by a practical and cost effective method that we propose offers enhanced specificity and sensitivity over biochemical markers of bone turnover.

The most commonly consumed and most extensively studied phytoestrogens are derived from soybeans. A recent metaanalysis of 10 randomized controlled trials of soy isoflavone intake on spinal bone mineral density in peri- or postmenopausal women found a significant increase with isoflavone intakes greater than 90 mg/d (28.5 mg/cm2, 95% confidence interval 8.4–48.6 mg/cm2) and an intervention period lasting 6 months or more (27 mg/cm2, 95% confidence interval 8.3–45.8 mg/cm2) (24). Our study shows that soy isoflavones ingested in quantities exceeding 90 mg/d suppresses bone resorption over a 50-d intervention period. The total isoflavone doses in the present study were higher than the highest dose in our previous study (220 vs. 135.5 mg total aglycone isoflavone units per day), which showed no effect on bone resorption (6), and they are also higher than would be consumed on a typical Asian diet (24). However, intakes did not exceed intervention doses of the synthetic isoflavone, ipriflavone, which was not found to be effective in preventing bone loss in a metaanalysis (23). The isoflavone profile of the soy cotyledon-derived dietary supplements of the present study was similar to our previous study but with a higher proportion of genistein-like isoflavones (73 vs. 56%) (8).

The difference between efficacy of soy germ and soy cotyledon supplements may be due to the somewhat higher total isoflavone intake on the soy cotyledon intervention (220 vs. 153 mg/d) and to differences in isoflavone profile of the products. The soy germ supplement was half as effective as the soy cotyledon supplement, and it contained more daidzein-like isoflavones (40%) and glycitein-like isoflavones (48%), but less genistein-like isoflavones (12%). Serum genistein levels in subjects averaged 4 times higher during the soy cotyledon than during the soy germ intervention (3489 ± 3172 vs. 835 ± 694 nmol/liter) without higher total serum isoflavone levels being attained, although the variation was large. Thus, it would appear that genistein is the more effective isoflavone. Genistein supplementation was as effective as hormone replacement therapy in reducing bone mineral density loss of the femur and lumbar spine in a 1-yr trial in postmenopausal women (25) and was effective after 24 months in a follow-up study, which showed a constant decrease in bone resorption. There are numerous proposed (26) mechanisms by which genistein improves bone health from direct genomic estrogen receptor-mediated effects to nongenomic actions such as protein tyrosine kinase inhibition. Suppression of bone resorption can occur through inhibition of osteoclastogenesis or direct inhibition of osteoclasts. Mixtures of different isoflavones may not optimize efficacy (27). Each isoflavone has a unique structure that very specifically affects its capacity to competitively bind estrogen receptors and maintain binding affinity relative to other isoflavones present, and furthermore, structure dictates the subsequent potency of its activity as a selective estrogen receptor modulator.

The dominant isoflavone in the red clover supplement was formononetin (78%) and the second most abundant isoflavone was biochanin A (4′-methoxygenistein) (16%) which are not present in soy. Bone resorption was not significantly (P = 0.09) reduced by the red clover supplement, possibly attributable to the lower dose and approximately 50% reduction in serum total isoflavones. To the extent that genistein may be the most bone active isoflavone, substantially increasing the dose of red clover supplementation, which is only 1.4% genistein (and 16% genistein precursor, biochanin A), would still not have been as effective as soy cotyledon. Nevertheless, 6 months of therapy with this supplement at doses of 57 or 85.5 mg/d resulted in a 4.0 and 3.0% increase, respectively (P = 0.002 and 0.023), in forearm bone mineral density in postmenopausal women (19).

The kudzu contained 14% daidzein-like isoflavones and 85% puerarin. Puerarin is unique in that it contains a −C-C-glucoside rather than a −C-O-glucoside bond and consequently is absorbed intact without metabolism (28). This isoflavone was ineffective at reducing bone resorption, even though serum isoflavone levels were as high as with the soy supplements.

The antiresorptive potential of the dietary supplements largely reflected the serum genistein levels achieved during intervention. Serum concentrations of the presumably bioactive gut microbial metabolites of daidzein, equol, and O-desmethylangolensin (29) were unrelated to bone resorption response to dietary interventions. Five of the 11 subjects were equol producers.

The sensitivity of the 41Ca technique was demonstrated by the ability to significantly (P < 0.0001) detect suppression of net bone resorption by estrogen therapy and the bisphosphonate risedronate in just four to six women. Similarly, Denk et al. (30) demonstrated a significant shift in urinary 41Ca excretion after 6 months of risedronate therapy in six postmenopausal women, reflecting the significant increase in spine bone mineral density by 3%. The magnitude of effect in shifting 41Ca to Ca ratios by risedronate therapy was similar to changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover. The intraindividual variation in measurements of 41Ca were small (similar in magnitude to measurement precision) in contrast to biomarkers of bone turnover (10–45%). In the small cohort in the present study, urinary biochemical markers of bone turnover were not significantly different among interventions due in part to measurements only being taken once at the end of each intervention rather than at each collection for 41Ca analysis and in part to their inherent lack of specificity and large inherent variability compared with 41Ca (30,31). Via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, the time required to see a response in areal bone mineral density and observe a change of the order of 1.2–4.7% (CV 1–2%) from an estrogen or risedronate intervention has been shown to be long (32,33,34). In this study, we were able to measure an estrogen- and risedronate-induced response via an approximately 25% effect on 41Ca excretion (CV 1.2%) in just 50 d.

The main strength of our study was the ability of the 41Ca method to compare multiple interventions in a small cohort of postmenopausal women. A limitation of our study was that our small subject population was homogeneous, i.e. all healthy white postmenopausal women living in the Midwest, which limits generalizability of results. Other limitations include the practical use of commercially available supplements, which precluded matching the dose, size, and shape of tablets. We have not verified which isoflavone or dose is most effective at suppressing bone loss. Our short-term study could not assess long-term efficacy or safety of the interventions.

The phytoestrogen preparations investigated in this study were variably efficacious with respect to suppressing bone loss. Moreover, all isoflavone effects were modest compared with estrogen or risedronate therapy. The most effective phytoestrogen treatment was the soy isoflavone preparation containing high levels of genistein. In that they are natural selective estrogen receptor modulators, they may be better tolerated in the long term than estrogen or bisphosphonates. Future research should be aimed at long-term efficacy and safety and identifying the most effective single isoflavone or isoflavone compound and dose.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical support of Anna Kempa-Steczko, Jane Einstein, Ron McClintock, and Alereza Arabshahi.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant P50-AT00477 from the National Institutes of Health. Prevastein was supplied by Cognis, Soylife EXTRA by Acatris (now Frutarom), and Rimostil by Novagen.

This work was presented at The American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, 28th Annual Meeting, 2006, Philadelphia, PA [Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 21 (S1):S184, 2006].

Disclosure Summary: C.M.W. is on the advisory boards of Pharmavite and Wyeth Global Nutrition. S.B. has a U.S. patent for the use of conjugated isoflavones in the prevention of osteoporosis. Other authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online July 7, 2009

Abbreviations: CV, Coefficient of variation; RR, relative resorption.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2004 Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators 2002 Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner B, Fritsch B, Von Tresckow E, Bartl C 2007 Bisphosphonates in medical practice: actions, side effects, indications, strategies. Berlin; New York: Springer; 61–62 [Google Scholar]

- Reinwald S, Weaver CM 2006 Soy isoflavones and bone health: a double-edged sword? J Natural Products 69:450–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CM, Spence CM, Lipscomb ER 2001 Phytoestrogens and bone health. In: Burkhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, eds. Nutritional Aspects of Osteoporosis. Proceedings of the Symposium on Nutritional Aspects of Osteoporosis. Nutr. Aspects of Osteo. Chap 28; 315–324 [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KDR 1998 Phytoestrogens: the biochemistry, physiology, implications for human health and soy isoflavones. Am J Clin Nutr 68:1333S–S1465S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Li Q, Gao YT, Zheng W 2005 Prospective cohort study of soy food consumption and risk of bone fracture among postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 165:1890–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong JMK, Martin BR, Jackson GS, Elmore D, McCabe GP, Nolan JR, Peacock M, Weaver CM 2007 Soy isoflavones do not affect bone resorption in postmenopausal women: a dose response study using a novel approach with 41Ca. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:577–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith HP, Collison MW 2001 Improved methods for the extraction and analysis of isoflavones from soy-containing foods and nutritional supplements by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and lipid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 913:397–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Coward L, Kirk M, Sfakianos J 1998 HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis of isoflavones. Exp Biol Med 217: 254–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SPHT, Beck B, Bierman JM, Caffee MW, Heaney RP, Holloway L, Marcus R, Southon JR, Vogel JS 2000 The study of skeletal calcium metabolism with 41Ca and 45Ca. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 172:930–933 [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CM, Rothwell AP, Wood KV 2006 Measuring calcium absorption and utilization in humans. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 9:568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney RP, Recker RR 1998 Estimating true fractional calcium absorption. Ann Intern Med 108:905–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tioshirani R 1993 An introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman, Hall [Google Scholar]

- Alekel DL, Germain AS, Peterson CT, Hanson KB, Stewart JW, Toda T 2000 Isoflavone-rich soy protein isolate attenuates bone loss in the lumbar spine of perimenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 72:844–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter SM, Baum JA, Teng H, Stillman RJ, Shay NF, Erdman JW 1998 Soy protein and isoflavones: their effects on blood lipids and bone density in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 68(Suppl):1375S–1379S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangen KE, Duncan AM, Merz-Demlow BE 2000 Effects of soy isoflavones on markers of bone turnover in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3043–3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydeking-Olsen E, Beck,-Jensen JE, Setchell KD, Holm-Jensen T 2004 Soymilk or progesterone for prevention of bone loss: a 2 year randomized, placebo-controlled diet. Eur J Nutr 43:246–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton-Bligh PB, Baber RJ, Fulcher GR, Nery M-L, Moreton T 2001 The effect of isoflavones extracted from red clover (Rimostel) on lipid and bone metabolism. Menopause 28:259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JJ, Chen X, Boass A, Symons M, Kohlmeier M, Renner JB, Garner SC 2002 Soy isoflavones: no effects on bone mineral content and bone mineral density in healthy, menstruating young adult women after one year. J Am Coll Nutr 21:388–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JC, Satpathy R, Rafferty K, Haynatzka V 2004 The effect of soy protein isolate on bone metabolism. Menopause 11:290–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreijkamp-Kaspers S, Kok L, Grobbee DE, de Haan EH, Aleman A, Lampe JW, van der Schouw YT 2004 Effect of soy protein containing isoflavones on cognitive function, bone mineral density, and plasma lipids in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandersen P, Toussaint A, Christiansen C, Devogelaer JP, Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Gennari C, Reginster JY 2001 Ipriflavone in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285:1482–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DF, Qin LQ, Wang PY, Katok R 2008 Soy isoflavone intake increases bone mineral density in the spine of menopausal women: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 27:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito N, Crisafulli A, Vergara C, Gaudio A, Lasco A, Frisina N, D'Anna R, Corrado F, Pizzoleo MA, Cincotta M, Altavilla D, Ientile R, Squadrito F 2002 Effect of genistein and hormone-replacement therapy on bone loss in early postmenopausal women: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Bone Miner Res 17:1904–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini H, Minutoli L, Polito F 2007 Effect of the phytoestrogen genistein on bone metabolism in osteopenic postmenopausal women. Ann Internal Med 146:839–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsson MC, Islander U, Moverare S, Ohlsson C, Carlsten H 2005 Estrogenic agonism and antagonism of the soy isoflavone genistein in uterus, bone and lymphopoiesis in mice. APMIS 113:317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasain JK, Jones K, Brissie N, Moore R, Wyss JM, Barnes S 2004 Identification of puerarin and its metabolites in rats by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem 52:3708–3712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C, Newton KM, Bowles EJ, Yong M, Lampe JW 2008 Demographic anthropometric, and lifestyle factors and dietary intakes in relation to daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes among premenopausal women in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 87:679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk E, Hillegonds D, Hurrell RF, Vogel J, Fattinger K, Häuselmann HJ, Kraenzlin M, Walczyk T 2007 Evaluation of 41calcium as a new approach to assess changes in bone metabolism: effect of a biophosphonate intervention in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Bone Miner Metab 22:1518–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibel MJ 2005 Biochemical markers of bone turnover. Part 1: biochemistry and variability. Clin Biochem Rev 26:97–122 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villareal DT, Binder EF, Williams DB, Schechitman KB, Yarasheski KE, Kohrt WM 2001 Bone mineral density response to estrogen replacement in frail elderly women. JAMA 286:815–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JY, Ho AY, Ip TP, Lee G, Kung AW 2005 The efficacy and tolerability of risedronate on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in osteoporotic Chinese women: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Bone 36:358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ST, Ericksen EF, Davidson M, Ettinger MP, Moffett Jr AH, Baylink DJ, Crusan CE, Chines AA 2001 Effect of combined risedronate and hormone replacement therapies on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1890–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]