Abstract

Although approximately 45 percent of smokers in the US are women, the influence of sex on nicotine dependence remains incompletely understood. Evidence from preclinical and clinical studies indicates that there are significant sex differences in nicotine’s effects. The goal of this report was to determine if men and women differ in their acute response to intravenous (IV) nicotine, which has not been examined in previous studies. Twelve male and 12 female smokers received saline followed by 0.5 and 1.0 mg /70 kg nicotine intravenously. In response to nicotine, women compared to men, had enhanced ratings for “drug strength,” “head rush,” and “bad effects.” Women and men experienced similar suppression of smoking urges by nicotine as assessed by the Brief Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (BQSU). Nicotine-induced heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure increases were also similar in magnitude in men and women. Our findings, consistent with several previous studies, support greater sensitivity of female smokers to some but not all of the subjective effects of nicotine. Further studies are warranted to examine the role of this differential nicotine sensitivity to development of nicotine dependence and response to nicotine replacement treatments in men and women.

Keywords: Nicotine, IV nicotine, Sex differences, Gender differences

Introduction

Although women represent approximately 45 percent of the smokers in the U.S., the moderating influence of sex on the initiation and maintenance of nicotine dependence is not fully understood (Centers for Disease Control, 2005). Several lines of evidence suggest that this may be an important area to pursue. For example, women smoke fewer cigarettes, take fewer puffs with shorter puff duration and volume, and have lower plasma concentrations of nicotine than men (Battig, Buzzi, & Nil, 1982; Eissenberg, Adams, Riggins, & Likness, 1999; Hofer, Nil, Wyss, & Battig, 1992; Zeman, Hiraki, & Sellers, 2002). In spite of smoking fewer cigarettes and having lower nicotine intake than men, women may be more vulnerable to smoking-related morbidity, such as lung cancer (Stabile & Siegfried, 2003). In addition, women appear to be less likely to quit smoking than men either with or without smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (Cepeda-Benito, Reynoso, & Erath, 2004; Killen, Fortmann, Varady, & Kraemer, 2002; Scharf & Shiffman, 2004; Wetter et al., 1999). These studies suggest that men and women differ in their level of nicotine intake and response to quit attempts.

Since cigarette smoke contains numerous compounds in addition to nicotine (Hoffmann & Wynder, 1986), investigation of sex differences in nicotine effects requires direct nicotine administration. Most notably, in a series of human studies, Perkins and colleagues have examined sex differences in response to nicotine nasal spray. Female smokers, without previous discrimination training, were less able to discriminate the effect of nicotine nasal spray over a broad range of doses, compared to males (Perkins, 1995). In addition, among those quitting smoking, men but not women, self-administered nicotine nasal spray more than placebo suggesting sex differences in the reinforcing effects of nicotine (Perkins, D'Amico et al., 1996). Since nicotine seems to be less reinforcing in women, Perkins and coworkers have suggested that non-nicotine smoking stimuli may be more reinforcing in women, compared with men (Perkins, 1996; Perkins, Jacobs, Sanders, & Caggiula, 2002). More recently, Perkins et al reported that women non-smokers were also less sensitive than men to the subjective effects of nicotine, administered via nasal spray (Perkins et al., 2009). However, additional studies have suggested that women are more sensitive to other effects of nicotine. For example, female smokers, compared to males, were found to be more sensitive to the subjective and physiological effects from oral nicotine (Netter, Muller, Neumann, & Kamradik, 1994), and to the subjective effects from intranasal nicotine (Myers, Taylor, Moolchan, & Heishman, 2008). In addition, women were also more sensitive to nicotine-induced reduction in smoking urges. Thus, nicotine sensitivity does not differ uniformly between male and female smokers, and important asymmetries have been described.

Sex differences in nicotine responses have also been examined in rodents using a wide range of outcome measures. For avoidance learning, antianxiety and antinociceptive effects, male rodents have been reported to be more sensitive to nicotine effects than females (Damaj, 2001; Hatchell & Collins, 1980; Yilmaz, Kanit, Okur, & Pogun, 1997). In contrast, female rats were more sensitive to nicotine-induced behavioral sensitization, cortisol and ACTH release, and weight reduction than male rats (Booze et al., 1999; Harrod et al., 2004). Further, following cessation of nicotine infusion, weight gain was greater in female than in male rats (Grunberg, Bowen, & Winders, 1986). Sex differences have also been observed for nicotine self-administration in rats (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Donny et al., 2000) and mice (Siu, Wildenauer, & Tyndale, 2006). In a study by Donny et al., female rats acquired nicotine administration faster than males under a fixed-ratio schedule and also worked harder than males to obtain nicotine under a progressive ratio schedule, suggesting a greater sensitivity of female rats to the reinforcing effects of nicotine (Donny et al., 2000). Together, these preclinical and clinical studies show seemingly discordant findings regarding sex differences in nicotine effects. Many factors including differences in outcome measures, baseline nicotine intake, tolerance development as a result of chronic nicotine exposure and route of administration for nicotine may contribute to these findings.

In order to further characterize sex differences in response to nicotine, we conducted a series of analyses on a pooled dataset from two human laboratory studies in which male and female smokers received successive doses of IV nicotine (0.5 and 1.0 mg/70 kg nicotine). The advantages of the IV route include rapid nicotine delivery, comparable to the bolus effect of smoking, and accurate dosing which has been difficult to achieve with other routes of nicotine delivery. In addition, IV nicotine, similar to smoking, produces “drug liking” and “good drug effects”, which are not typically observed with other pure nicotine formulations (e.g., nicotine gum, patch or nasal spray) (Harvey et al., 2004; Houtsmuller, Fant, Eissenberg, Henningfield, & Stitzer, 2002; Houtsmuller, Henningfield, & Stitzer, 2003; Jones, Garrett, & Griffiths, 1999). Moreover, since the IV route is commonly used to administer nicotine to laboratory animals, this route provides an opportunity to make translational comparisons between human and animal models of nicotine effects. To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing IV nicotine responses in male and female smokers.

Method

Participants

Participants were 12 female and 12 male non-treatment seeking smokers who participated in one of two human laboratory nicotine studies (for complete details see, (Sofuoglu, Mooney, & Waters, 2008; Sofuoglu, Poling, Mouratidis, & Kosten, 2006). They were recruited from the New Haven, Connecticut area by newspaper advertisements. Participants had normal physical, laboratory and psychiatric examinations and were not dependent on alcohol or on any drugs other than nicotine. Experimental sessions were conducted in the Biostudies Unit located at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (West Haven campus) and participants were paid for participation. This study was approved by the VA Connecticut Healthcare System Human Subjects Subcommittee, and all participants provided written, informed consent prior to their entry into the study.

Procedures

The data presented were collected during the adaptation session of 2 studies. During the adaptation session, identical procedures were followed for both studies. Participants were instructed not to smoke after midnight on the adaptation day, thus remaining abstinent for 8 hours before presenting at the laboratory at 8 AM. Smoking abstinence was verified using breath carbon monoxide levels (<10 parts-per-million). Before the sessions started, an indwelling IV catheter was placed in the participant’s antecubital vein for nicotine infusion and phlebotomy. During the sessions, participants were sitting on a comfortable recliner chair. Approximately, 45 minutes after the IV catheter placement, baseline measurements were obtained and participants were given saline followed by 2 escalating doses of nicotine (0.5 and 1.0 mg/70 kg) intravenously. Participants were told that they would be receiving saline and nicotine doses but were not informed in what order they would be administered. The injections were delivered over 60 seconds, and were separated by a 30-minute interval. Cardiac rhythm was monitored continuously during sessions, and 12-lead ECGs were obtained before and at the end of the session.

Nicotine Administration

Nicotine bitartrate was obtained from Interchem Corporation (Paramus, New Jersey). Nicotine samples were prepared by the research pharmacy at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in a 5 cc volume of saline. In order to examine the dose-response effects of nicotine, participants were administered placebo (saline) followed by 2 ascending doses of nicotine (0.5 and 1.0 mg/70 kg). This escalating dosing procedure within the same session has been successfully used in previous studies for other drugs of abuse (Chait, Corwin, & Johanson, 1988; Walsh, Preston, Sullivan, Fromme, & Bigelow, 1994; Walsh, Sullivan, Preston, Garner, & Bigelow, 1996). The nicotine doses selected were within the nicotine dose range that has been shown to produce robust and reproducible subjective and physiological effects (Henningfield, Miyasato, & Jasinski, 1985; Jones et al., 1999; Sofuoglu, Babb, & Hatsukami, 2003; Sofuoglu, Mouratidis, Yoo, Culligan, & Kosten, 2005).

Outcome measures

Biochemical measures

The biochemical measures were expired CO and plasma cotinine levels obtained to verify abstinence from smoking and level of smoking, respectively. These measures were obtained at the beginning of the session.

Physiological measures

The physiological measures were systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate. These measures were obtained 5 minutes before and 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 15 minutes after saline or nicotine injections.

Subjective measures

The subjective effects of nicotine were assayed with four instruments. The Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ), used to assess the acute subjective effects of nicotine, consists of 5 items: “drug strength,” “good effects,” “bad effects,” “head rush” and “like the drug.” Participants rated these items on a 100 mm scale, from 0 “not at all” to 100 “extremely.” The Brief Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (BQSU), is a 10-item scale originally developed by Tiffany and Drobes (Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001; Tiffany & Drobes, 1991). Smokers were asked how strongly they agree or disagree with items on a 7-point Likert scale. This scale has been found to be highly reliable and reflects levels of nicotine deprivation (Bell, Taylor, Singleton, Henningfield, & Heishman, 1999; Morgan, Davies, & Willner, 1999). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) is a 20-item scale that assesses both negative and positive affective states (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Participants rated adjectives describing affective states on a 5-point Likert scale. The Profile of Mood States (POMS), Bipolar Form, is a 72–item rating scale used to measure the effects of medication treatments on mood (McNair, Lorr, & Dropperman, 1988). The POMS has 6 subscales: (1) composed-anxious; (2) agreeable-hostile; (3) elated-depressed; (4) confident-unsure; (5) energetic-tired; (6) clear headed-confused. For all subscales, higher scores are reflective of more positive mood states.

The DEQ was given 5 minutes before and 1, 3, 5, 8, and 10 minutes after saline or nicotine injections. The POMS, PANAS and the BQSU were given twice: at the beginning and end of the session.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted with the Statistical Analysis System Version 9.1.3. Unless otherwise stated, values of p<.05 were considered statistically significant, based on two-tailed tests. Type I error rate in post-hoc tests was maintained through Bonferroni adjustments. Comparisons between the two study samples and between men and women in the pooled dataset were conducted using t-tests and Fisher exact tests. To examine sex effects on outcome measures, we computed change scores. For blood pressure, heart rate, and DEQ measurements during IV saline or nicotine administration, multiple measurements were collected. In order to simplify the analysis, a change score (maximum post dose score minus predose baseline) for each dose (saline, 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg nicotine/70 kg) was calculated as a summary index. For the POMS, PANAS, and the BQSU, change scores from before and after the session were analyzed.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Comparisons between males and females in the pooled sample of 24 smokers are presented in Table 1. While no sex differences were observed in smoking habits and history, women in the pooled sample were more likely to be African-American and older than men (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics and smoking characteristics of male and female smokers

| Women (n = 12) |

Men (n = 12) |

P-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 1 | 8.3 | 6 | 50.0 | 0.05* |

| African-American | 10 | 83.4 | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Other | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 16.7 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 39.8 | 5.7 | 31.5 | 10.4 | 0.02* |

| Years of smoking | 19.7 | 9.0 | 16.1 | 7.9 | 0.3 |

| Cigarettes/day | 18.3 | 3.2 | 17.9 | 8.1 | 0.9 |

| FTND score | 5.0 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| Plasma cotinine valuesab | 225 | 121 | 186 | 132 | 0.5 |

Note. p<0.05

ng/mL

t-test performed on log-normalized plasma cotinine values.

Physiological measures

Analyses of change scores from pre-dose to maximum post-dose revealed significant main effects for dose for all three outcomes, heart rate, F(2, 21) = 13.39, p = 0.0002, diastolic blood pressure, F(2, 21) = 3.66, p = 0.0432, and systolic blood pressure, F(2, 43.1) = 11.32, p = 0.0001. However, no sex or sex × dose interaction effects were observed. Dose effects were further examined through post-hoc comparisons using Bonferroni adjustments. In the case of heart rate, both active doses generated significantly greater increases compared to placebo (p<.01). For diastolic blood pressure, only the 0.5 mg dose significantly increased blood pressure compared to placebo (p<.01). The 1 mg dose of nicotine produced significantly greater increases in systolic blood pressure than the 0.5 and placebo doses (p<.01).

Subjective Measures

DEQ

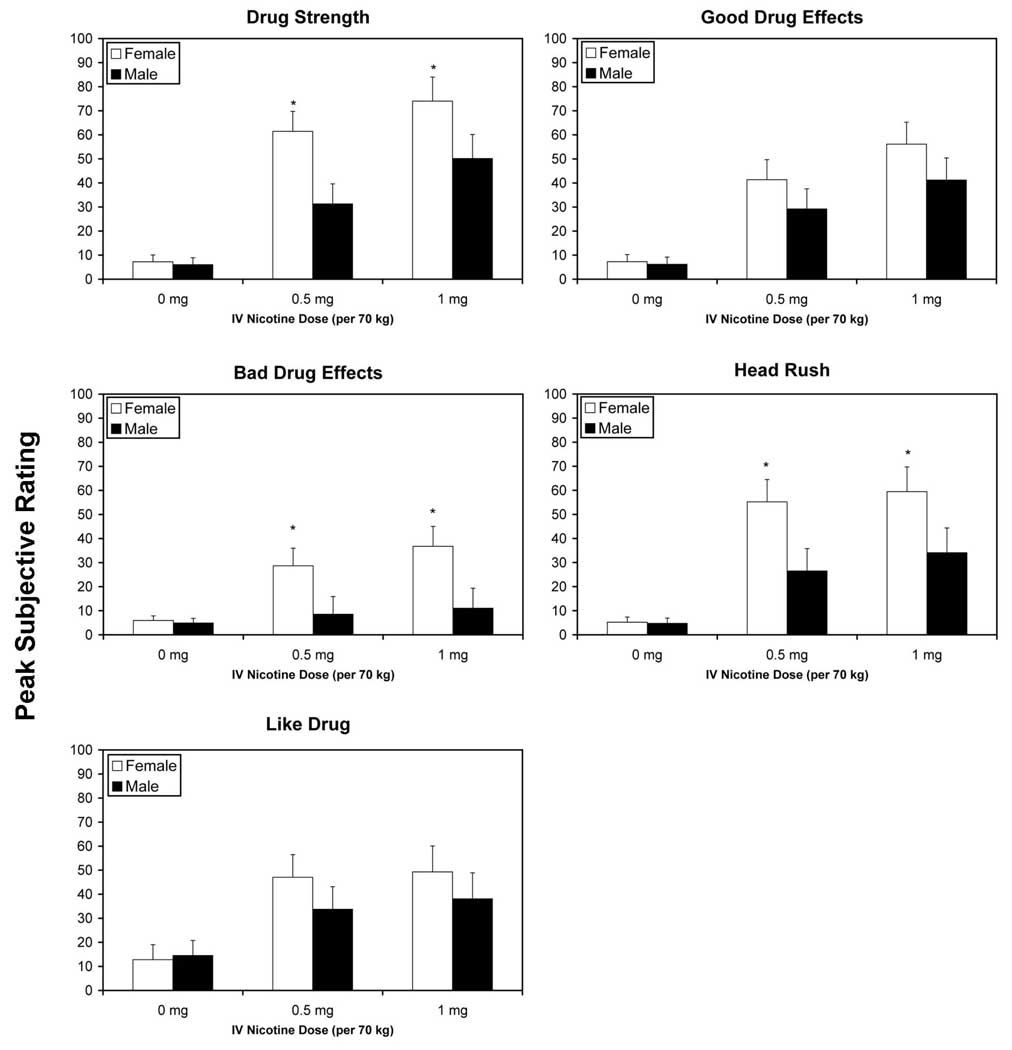

Analyses of change scores from pre-dose to maximum post-dose ratings on the DEQ, revealed significant main effects for dose on all five sub-scales, “drug strength”, F(2, 21) = 31.12, p < 0.0001, “good drug effects”, F(2, 21) = 19.44, p < 0.0001, “bad drug effects”, F(2, 21) = 5.39, p = 0.0129, “head rush”, F(2, 21) = 18.05, p <0.0001 and “like drug”, F(2, 21) = 9.11, p = 0.0014. In all cases, active doses of nicotine produced significantly greater changes than placebo, (Bonferroni-adjusted p<.05). For “drug strength”, the 1 mg dose of nicotine also produced greater effects than the 0.5 mg dose. Females reported greater subjective effects than males on three scales, “drug strength”, F(1, 23) = 4.95, p = 0.0361, “bad drug effects,” F(1, 23) = 4.40, p = 0.0472, and “head rush”, F(1, 22.8) = 4.34, p = 0.0487. For all 3 items, significant sex differences were observed under the 0.5 and 1 mg nicotine conditions (Bonferroni-adjusted p values<.05).

BQSU

For the comparison of tobacco craving prior to the session and at the end (i.e., after 3 dose administrations), both male and female smokers showed a similar reductions in craving on both factors.

POMS

The POMS scores, changes from the beginning of the session to the end (i.e., after 3 dose administrations), were significant only for “energetic-tired”, F(1, 21) = 6.51, p = 0.0186, with females decreasing on this scale, becoming more tired (Mean Change = −1.3 , SE = 1.1), and males increasing on this scale, becoming more energetic (Mean Change = 2.9, SE = 1.1).

PANAS

Women and men reported similar changes in positive affect of the PANAS from the beginning of the session to the end (i.e., after 3 dose administrations). A statistical trend was observed for negative affect, F(1, 21) = 3.55, p = 0.0743, with females decreasing on this negative affect (Mean Change = 1.5 , SE = 1.1), and males increasing in negative affect (Mean Change = −1.6, SE = 1.2).

Exploratory Analyses

Since men and women showed an unbalanced racial distribution (see Table 1), we conducted exploratory analyses on 19 participants (excluding 2 Hispanic and 1 Asian participant). We repeated the analyses above including race and its interaction with gender. No effects of race or race × gender were observed.

Discussion

The main finding of this report was that female smokers were more sensitive to some of the subjective responses to IV nicotine than men including the rating of “drug strength,” “bad effects,” and “head rush”. Sex differences for the rating of “good effects” and “drug liking,” did not reach statistical significance. Our findings are consistent with a previous study, which examined the dose-dependent effects of nicotine nasal spray (1 and 2 mg) on the subjective, physiological and cognitive performance outcomes under both nicotine deprived and non-deprived conditions (Myers et al., 2008). In that study, female smokers were more sensitive than men, especially under non-deprived conditions, to the acute subjective effects of nicotine including the rating of jitteriness as well as negative and positive mood. Other studies using the nicotine patch (Evans, Blank, Sams, Weaver, & Eissenberg, 2006) or oral nicotine (Netter et al., 1994) reported similar findings, with women being more sensitive than men to the subjective effects of nicotine. Our analyses extend these findings further by using IV nicotine administration and weight-based nicotine dosing, which have not been done in previous studies mentioned above (Evans et al., 2006; Myers et al., 2008; Netter et al., 1994). Altogether, these studies demonstrate greater sensitivity of women, relative to men, to some of the subjective nicotine effects.

In contrast to these findings, Perkins et al reported that women were less sensitive than men to nicotine nasal spray for outcomes including nicotine reinforcement and discrimination, as well as subjective drug effects (Perkins et al., 2009). The reasons for these discrepant findings are not clear, however, route of administration might be an important factor. While intravenous nicotine produces robust self-report drug liking and good effects and is self-administered more than placebo (Harvey et al., 2004; Sofuoglu, Yoo, Hill, & Mooney, 2008), nicotine nasal spray is considerably aversive and produces minimal or no drug liking or good drug effects, compared to placebo and is not self-administered more than placebo by smokers (Perkins, Grobe, Weiss, Fonte, & Caggiula, 1996; Schneider et al., 2005; Schuh, Schuh, Henningfield, & Stitzer, 1997). As a future study, it will be important to evaluate sex differences in nicotine reinforcement using intravenous nicotine administration.

Indices of mood, the POMS and PANAS, did not reveal significant sex differences in subjective response to nicotine, except the rating of the POMS scale “energetic-tired” While women became more tired, men became more energetic. These findings are consistent with preclinical studies indicating that sex differences in nicotine responses depend on the outcome measure.

These sex differences were not explained by variation in baseline nicotine intake since plasma cotinine levels were not different between male and female smokers. Similarly, measures of nicotine addiction including FTND scores, cigarettes smoked per day, and years of smoking did not differ between male and female smokers and are thus unlikely contributors to these findings. In our analysis, we used age as a covariate, since women in our study were older than men. An important question that was not addressed in our study is whether sex differences in nicotine pharmacokinetics contribute to our findings. Previous studies have shown that women metabolize nicotine faster than men (Benowitz & Hatsukami, 1998; Benowitz, Lessov-Schlaggar, Swan, & Jacob, 2006). However, since not all the outcome measures showed sex differences, including the cardiovascular responses to nicotine, pharmacokinetic differences likely do not account for the observed sex differences. Another possibility is whether women have greater subjective responses to IV drugs than men in general. Such a difference might have potentially contributed to our findings. However, in our study, subjective responses to IV saline were comparable in men and women. Further, in another study women and men showed similar subjective responses to IV cocaine (McCance-Katz, Hart, Boyarsky, Kosten, & Jatlow, 2005). These findings do not support a general gender differences in subjective response to IV drugs.

Our study is limited in several ways. First, although our male and female smokers had mostly comparable characteristics, they differed in age and racial distribution. Both these variables may potentially influence our results. Although the potential influence of both variables was examined in additional analysis, future studies with balanced men and women smokers are warranted. Second, participants in our study were non-treatment seeking smokers. The generalizability of these findings to treatment seeking smokers might be limited. Third, we did not experimentally control for the menstrual cycle phase of female smokers, although previous studies have not supported menstrual cycle influence on nicotine sensitivity (Marks et al. 1999).

To summarize, women smokers, relative to men, had greater sensitivity to some of the subjective effects from IV nicotine. These findings, together with previous studies, support greater sensitivity of female smokers to some of the subjective effects of nicotine. Further studies are warranted to examine the role of this differential nicotine sensitivity to development of nicotine dependence and response to nicotine replacement treatments in men and women.

Fig. 1.

The mean (with standard error of the mean - SEM) peak subjective responses to saline, 0.5 and 1.0 mg/ 70 kg intravenous nicotine in male and female smokers for the five scales of the DEQ. Bars represent the mean maximum score. *p<.05 after Bonferroni adjustment.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Veterans Administration Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01-DA 14537. The authors were supported by career development awards, K02-DA-021304 (MS) and K01-DA-019446 (MM).

References

- Battig K, Buzzi R, Nil R. Smoke yield of cigarettes and puffing behavior in men and women. Psychopharmacology. 1982;76(2):139–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00435268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SL, Taylor RC, Singleton EG, Henningfield JE, Heishman SJ. Smoking after nicotine deprivation enhances cognitive performance and decreases tobacco craving in drug abusers [In Process Citation] Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(1):45–52. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Hatsukami DK. Gender diffferences in the pharmacology of nicotine addiction. Addiction Biology. 1998;3:383–404. doi: 10.1080/13556219871930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, Jacob P., 3rd Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(5):480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booze RM, Welch MA, Wood ML, Billings KA, Apple SR, Mactutus CF. Behavioral sensitization following repeated intravenous nicotine administration: gender differences and gonadal hormones. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64(4):827–839. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 1997–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(25):625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda-Benito A, Reynoso JT, Erath S. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: differences between men and women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(4):712–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait LD, Corwin RL, Johanson CE. A cumulative dosing procedure for administering marijuana smoke to humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;29(3):553–557. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib MA, Craven LA, et al. Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180(2):258–266. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI. Influence of gender and sex hormones on nicotine acute pharmacological effects in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296(1):132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Rowell PP, Gharib MA, Maldovan V, Booth S, et al. Nicotine self-administration in rats: estrous cycle effects, sex differences and nicotinic receptor binding. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151(4):392–405. doi: 10.1007/s002130000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Adams C, Riggins EC, 3rd, Likness M. Smokers' sex and the effects of tobacco cigarettes: subject-rated and physiological measures. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(4):317–324. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Blank M, Sams C, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Transdermal nicotine-induced tobacco abstinence symptom suppression: nicotine dose and smokers' gender. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14(2):121–135. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg NE, Bowen DJ, Winders SE. Effects of nicotine on body weight and food consumption in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;90(1):101–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00172879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrod SB, Mactutus CF, Bennett K, Hasselrot U, Wu G, Welch M, et al. Sex differences and repeated intravenous nicotine: behavioral sensitization and dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78(3):581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DM, Yasar S, Heishman SJ, Panlilio LV, Henningfield JE, Goldberg SR. Nicotine serves as an effective reinforcer of intravenous drug-taking behavior in human cigarette smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175(2):134–142. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchell PC, Collins AC. The influence of genotype and sex on behavioral sensitivity to nicotine in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;71(1):45–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00433251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield JE, Miyasato K, Jasinski DR. Abuse liability and pharmacodynamic characteristics of intravenous and inhaled nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;234(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer I, Nil R, Wyss F, Battig K. The contributions of cigarette yield, consumption, inhalation and puffing behaviour to the prediction of smoke exposure. Clin Investig. 1992;70(3–4):343–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00184671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. Chemical constituents and bioactivity of tobacco smoke. IARC Sci Publ. 1986;(74):145–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsmuller EJ, Fant RV, Eissenberg TE, Henningfield JE, Stitzer ML. Flavor improvement does not increase abuse liability of nicotine chewing gum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72(3):559–568. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00723-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsmuller EJ, Henningfield JE, Stitzer ML. Subjective effects of the nicotine lozenge: assessment of abuse liability. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167(1):20–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Garrett BE, Griffiths RR. Subjective and physiological effects of intravenous nicotine and cocaine in cigarette smoking cocaine abusers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288(1):188–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Varady A, Kraemer HC. Do men outperform women in smoking cessation trials? Maybe, but not by much. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10(3):295–301. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF, Hart CL, Boyarsky B, Kosten T, Jatlow P. Gender effects following repeated administration of cocaine and alcohol in humans. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(4):511–528. doi: 10.1081/ja-200030693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Dropperman L. Profile of Mood States: Bipolar Form. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MJ, Davies GM, Willner P. The Questionnaire of Smoking Urges is sensitive to abstinence and exposure to smoking-related cues. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10(6–7):619–626. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CS, Taylor RC, Moolchan ET, Heishman SJ. Dose-related enhancement of mood and cognition in smokers administered nicotine nasal spray. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(3):588–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netter P, Muller MJ, Neumann A, Kamradik B. The influence of nicotine on performance, mood, and physiological parameters as related to smoking habit, gender, and suggestibility. Clin Investig. 1994;72(7):512–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00207480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Individual variability in responses to nicotine. Behavior Genetics. 1995;25(2):119–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02196922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Sex differences in nicotine versus non-nicotine reinforcement as determinants of tobacco smoking. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;4:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Coddington SB, Karelitz JL, Jetton C, Scott JA, Wilson AS, et al. Variability in initial nicotine sensitivity due to sex, history of other drug use, and parental smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1–3):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, D'Amico D, Sanders M, Grobe JE, Wilson A, Stiller RL. Influence of training dose on nicotine discrimination in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;126(2):132–139. doi: 10.1007/BF02246348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE, Weiss D, Fonte C, Caggiula A. Nicotine preference in smokers as a function of smoking abstinence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;55(2):257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Jacobs L, Sanders M, Caggiula AR. Sex differences in the subjective and reinforcing effects of cigarette nicotine dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163(2):194–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf D, Shiffman S. Are there gender differences in smoking cessation, with and without bupropion? Pooled- and meta-analyses of clinical trials of Bupropion SR. Addiction. 2004;99(11):1462–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider NG, Terrace S, Koury MA, Patel S, Vaghaiwalla B, Pendergrass R, et al. Comparison of three nicotine treatments: initial reactions and preferences with guided use. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182(4):545–550. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh KJ, Schuh LM, Henningfield JE, Stitzer ML. Nicotine nasal spray and vapor inhaler: abuse liability assessment. Psychopharmacology. 1997;130(4):352–361. doi: 10.1007/s002130050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu EC, Wildenauer DB, Tyndale RF. Nicotine self-administration in mice is associated with rates of nicotine inactivation by CYP2A5. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(3–4):401–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Babb D, Hatsukami DK. Labetalol treatment enhances the attenuation of tobacco withdrawal symptoms by nicotine in abstinent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(6):947–953. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Mooney M, Waters AJ. Effects of minocycline on intravenous nicotine responses and smoking behavior in overnight abstinent smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.11.004. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Mouratidis M, Yoo S, Culligan K, Kosten T. Effects of tiagabine in combination with intravenous nicotine in overnight abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181(3):504–510. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Poling J, Mouratidis M, Kosten T. Effects of topiramate in combination with intravenous nicotine in overnight abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(3–4):645–651. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Yoo S, Hill KP, Mooney M. Self-administration of intravenous nicotine in male and female cigarette smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(4):715–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabile LP, Siegfried JM. Sex and gender differences in lung cancer. J Gend Specif Med. 2003;6(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br J Addict. 1991;86(11):1467–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Preston KL, Sullivan JT, Fromme R, Bigelow GE. Fluoxetine alters the effects of intravenous cocaine in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;14(6):396–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Sullivan JT, Preston KL, Garner JE, Bigelow GE. Effects of naltrexone on response to intravenous cocaine, hydromorphone and their combination in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279(2):524–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Fiore MC, Young TB, McClure JB, de Moor CA, Baker TB. Gender differences in response to nicotine replacement therapy: objective and subjective indexes of tobacco withdrawal. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(2):135–144. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz O, Kanit L, Okur BE, Pogun S. Effects of nicotine on active avoidance learning in rats: sex differences. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8(2–3):253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman MV, Hiraki L, Sellers EM. Gender differences in tobacco smoking: higher relative exposure to smoke than nicotine in women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(2):147–153. doi: 10.1089/152460902753645281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]