Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine the age- and sex-specific prevalence and risk indicators of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need among a population-based sample of Latino adults.

METHODS

Self-identified Latinos 40 years of age and older (n = 6129) from six census tracts in La Puente, California, under-went a complete ophthalmic examination, and a home-administered questionnaire provided self-reported data on potential risk indicators. Uncorrected refractive error was defined as a ≥2-line improvement with refraction in the better seeing eye. Unmet refractive need was defined as having <20/40 visual acuity in the better seeing eye and achieving ≥20/40 after refraction (definition 1) or having <20/40 visual acuity in the better seeing eye and achieving a ≥2-line improvement with refraction (definition 2). Sex- and age-specific prevalence and significant risk indicators for uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need were calculated.

RESULTS

The overall prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was 15.1% (n = 926). The overall prevalence of unmet refractive need was 8.9% (n = 213, definition 1) and 9.6% (n = 218, definition 2). The prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and either definition of unmet refractive need increased with age (P < 0.0001). No sex-related difference was present. Older age, <12 years of education, and lack of health insurance were significant independent risk indicators for uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need.

CONCLUSIONS

The data suggest that the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need is high in Latinos of primarily Mexican ancestry. Better education and access to care in older Latinos are likely to decrease the burden of uncorrected refractive error in Latinos.

Visual impairment is one of the most significant public health problems affecting more than 3.4 million elderly Americans.1,2 Visual impairment including blindness costs the U.S. government more than $4 billion annually.1 Refractive error continues to be the leading cause of visual impairment across the United States and worldwide,3,4 and uncorrected refractive error can limit vision-dependent daily activities and lower the quality of life.5 Although the effect of uncorrected refractive errors on morbidity and mortality has been well documented in previous studies,6–11 presently, there is a limited pool of literature on uncorrected refractive error, especially among Latinos in the United States12—one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. population.13

According to the 2006 American Community Survey, there are currently 44.3 million Latinos in the United States, of which 28.3 million are of Mexican ancestry, accounting for 63.9% of Latinos and 9.5% of the country’s total population.13 However, Latinos remain underserved from a healthcare standpoint, and their rate of visual impairment is higher than that of non-Hispanic whites in the United States.14

The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES) is a population-based prevalence survey of ocular disease in Latinos, 40 years of age and older, in the City of La Puente in Los Angeles County, California. This study provided us with an opportunity to explore the occurrence of uncorrected refractive error in Latinos. Specifically, the purpose of this research was to estimate the sex- and age-specific prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need in a population-based sample of urban Latinos; to determine the relationships of various socioeconomic and medical risk indicators with uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need; and to compare the rates of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need in Latinos with those of other racial/ethnic groups.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The LALES study population consists of self-identified Latino residents of La Puente, California, aged 40 years or older. Details of the study design, sampling plan, and baseline data are reported elsewhere.15 In summary, a door-to-door census of all dwelling units within six census tracts in La Puente was performed, and eligible residents (40 years of age or older at the time of the census) who self-identified as Latino were invited to participate in both a home interview and a clinic examination. The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of LALES participants in La Puente were found to be similar to Latinos of Mexican-American ancestry in Los Angeles County, California, and in the United States15 as a whole. Informed consent was obtained from each subject after the nature and possible consequences of the study were described. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee of the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Study Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

After obtaining informed consent, we conducted a detailed in-home interview. The instrument gathered information on the following quantitative concepts: country of birth, acculturation, marital status, employment status, education level, annual income level, body mass index, smoking status, health and vision insurance, and healthcare and eye care utilization in the past 12 months. Specific features of the in-home interview, along with the details of how Mexican-American or Native American ancestry was attributed to a participant, have been presented elsewhere.15 The Cuellar nine-item acculturation scale was used to measure acculturation (1, lowest; 5, highest). Details of this instrument have been presented elsewhere.16,17

All eligible individuals were scheduled for a comprehensive eye examination, including visual acuity testing, which was performed in a standardized manner at the LALES Local Eye Examination Center (LEEC) in La Puente.

Visual Acuity Testing

Standard Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) protocols with a modified ETDRS distance chart that was transilluminated with a chart illuminator (Precision Vision, La Salle, IL)18 were used for each LALES participant to measure the best-corrected distance visual acuity in each eye with presenting correction (if any), at 4 m. Using different charts for each participant’s right and left eye, the examiner measured the presenting distance visual acuity for each eye (right eye followed by left eye) with the participant’s existing refractive correction. If the participant read fewer than 55 letters at 4 m in either eye, automated refraction was performed (Humphrey Autorefractor; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA), followed by subjective refraction with standard protocols. After refraction, the eye was retested to measure the best-corrected visual acuity in that eye. If the participant was unable to read letters at 4 m, visual acuity measurement and subjective refraction were performed at 1 m. If the participant was still unable to read the largest letters at a distance of 1 m, a semiquantitative estimate of the visual acuity (finger counting, hand motion, light perception, or no light perception) was made. A logarithmic E chart was used for participants who were unable to read the standard charts.

Quality control procedures were applied to all presenting visual acuity measurements of 20/40 or worse, in that they were confirmed independently by a second trained technician who was masked to the readings of the first technician. The intertechnician agreement for visual acuity measurements for degrees of visual impairment (none, mild, moderate, and severe) was very good (weighted κ [95% CI] for line-by-line agreement = 0.77 [0.68–0.86]).

Definitions

Uncorrected refractive error was defined as an improvement of two or more lines in visual acuity in the better seeing eye after refraction of the same eye. To facilitate comparisons, we used a similar definition of unmet refractive need as has been published.19 Definition 1 was defined as participants with or without existing correction who had a presenting visual acuity of worse than 20/40 in the better seeing eye, but who could achieve 20/40 or better with correction in that same eye. The foundation of this definition is rooted in the standard visual acuity needed to drive an automobile in the United States.20 To include participants who did not meet definition 1 but who could nevertheless benefit from refraction, we developed a second definition for unmet refractive need. Definition 2 was defined as participants with or without existing correction who had a presenting visual acuity of worse than 20/40 in the better seeing eye but who could achieve an improvement of two or more lines with correction in that same eye.

Statistical Analyses

The prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was calculated as the ratio of the number of individuals with uncorrected refractive error to the total number of individuals evaluated. The prevalence of the unmet refractive need was calculated for each of the two definitions as the ratio of the number of individuals with unmet refractive need to the total number of individuals evaluated. The relationship of age, sex, and other risk indicators to uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need was explored by using univariate and age-adjusted stepwise multivariate logistic regression procedures. Differences in the prevalence across age categories were tested using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. Candidate sociodemographic risk indicators included country of birth (United State vs. other), acculturation score using the Cuellar scale (low ≤1.9 vs. high >1.9), marital status (married, never married, widowed, or separated/divorced), employment status (employed, retired, or unemployed), education level (<12 years vs. ≥12 years), annual income level (<$20,000, $20,000–40,000, or >$40,000), history of smoking (nonsmoker, ex-smoker, or current smoker), health and vision insurance, and healthcare and eye care utilization in the past 12 months. Candidate clinical risk indicators included body mass index (BMI: normal, ≤24.9; overweight, 25.0–29.9; or obese, ≥30.0). All analyses were conducted at the 0.05 significance level (SAS software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Cohort

Of the 7789 individuals classified as eligible participants for LALES, 6357 (82%) completed the ophthalmic examination. Of the 6357 participants, 6129 (96%) completed both the in-home interview and the clinical examination. The primary analyses for this article were based on data from these 6129 participants. The majority (58%) of the participants were women; the average (±SD) age was 54.9 (±10.8) years; 94.7% were of Mexican-American ancestry, and 5.3% were of Native American ancestry. Details regarding nonparticipants have been presented elsewhere.15

Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Error and Unmet Refractive Need

Of the 6129 LALES participants, the overall prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was 15.1% (n = 926). When stratified by visual impairment (VI) categories, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error for no VI (presenting binocular distance visual acuity [PBDVA] >20/40), mild VI (PBDVA 20/40–20/63), and moderate/severe VI (PBDVA 20/80 to <20/200) were 11%, 65%, and 57%, respectively (P < 0.001).

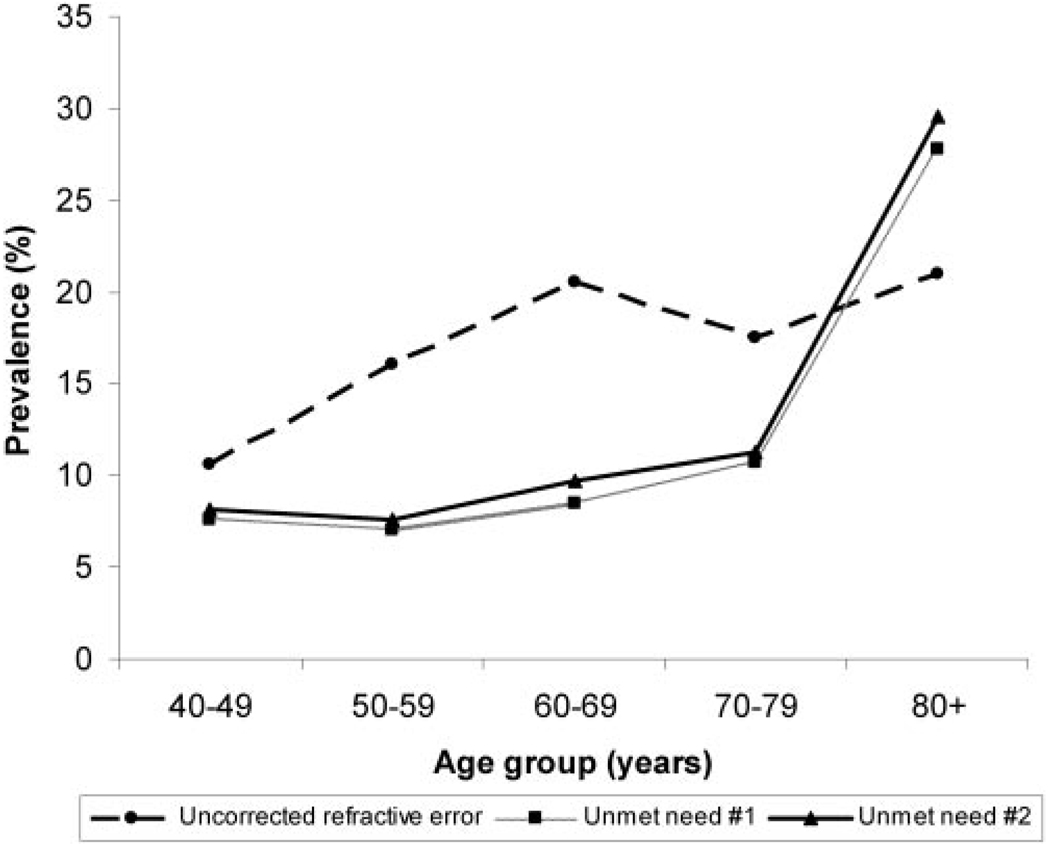

The sex- and age-specific prevalence of uncorrected refractive error based on two or more lines of improvement between presenting and best corrected visual acuity in the better seeing eye is presented in Table 1. The prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was similar in men and women (14.5% and 15.1%, respectively P = 0.24); there was no significant sex-associated difference across age groups. The prevalence of uncorrected refractive error increased with age (P < 0.0001, Cochran-Armitage trend test; Fig. 1); the prevalence was 10.6% in the youngest age group (40–49 years) and doubled to 21% in the oldest age group (≥80 years).

TABLE 1.

Sex- and Age-Specific Prevalence of Uncorrected Refractive Error and Unmet Refractive Need among LALES Participants

| Sex Frequency (%) | Age Group Frequency (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected Refractive Error Improvement |

Male (n = 2556) |

Female (n = 3573) |

Total (n = 6129) |

P | 40–49 (n = 2361) |

50–59 (n = 1853) |

60–69 (n = 1189) |

70–79 (n = 583) |

≥80 (n = 143) |

Total (n = 6129) |

P |

| ≥2Lines* | 370 (14.5) | 556 (15.1) | 926 (15.1) | 0.24 | 251 (10.6) | 299 (16.1) | 244 (20.5) | 102 (17.5) | 30 (21.0) | 926 (15.1) | <0.0001 |

| Sex Frequency (%) | Age Group Frequency (%) | ||||||||||

| Unmet Refractive Need | Male (n = 869) | Female (n = 1536) | Total (n = 2405) | P | 40–49 (n = 538) | 50–59 (n = 752) | 60–69 (n = 648) | 70–79 (n = 384) | ≥80 (n = 83) | Total (n = 2405) | P |

| Definition1† | 87 (10.0) | 126 (8.2) | 213 (8.9) | 0.13 | 41 (7.6) | 53 (7.0) | 55 (8.5) | 41 (10.7) | 23 (27.7) | 213 (8.9) | <0.0001 |

| Sex Frequency (%) | Age Group Frequency (%) | ||||||||||

| Unmet Refractive Need | Male (n = 822) | Female (n = 1456) | Total (n = 2278) | P | 40–49 (n = 521) | 50–59 (n = 715) | 60–69 (n = 610) | 70–79 (n = 354) | ≥80 (n = 78) | Total (n = 2278) | P |

| Definition2‡ | 88 (10.7) | 130 (8.9) | 218 (9.6) | 0.17 | 42 (8.1) | 54 (7.6) | 59 (9.7) | 40 (11.3) | 23 (29.5) | 218 (9.6) | <0.0001 |

Uncorrected refractive error was defined as an improvement of two or more lines in visual acuity in the better seeing eye after refraction of the same eye.

Participants, with or without existing correction, who had a presenting visual acuity of worse than 20/40 in the better seeing eye but could achieve 20/40 or better with correction in that same eye.

Participants, with or without existing correction, who had a presenting visual acuity of worse than 20/40 in the better seeing eye but could achieve an improvement in two or more lines with correction in that same eye.

FIGURE 1.

Age-specific prevalence rates of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study.

The sex- and age-specific prevalences of unmet refractive need are also presented in Table 1. Of the 6129 LALES participants, 2405 and 2278 individuals fit the criteria for definitions 1 and 2 of unmet refractive need, respectively. Similar to uncorrected refractive error, no significant sex-associated difference was noted (definition 1, P = 0.13; definition 2, P = 0.17). Overall, the prevalence of unmet refractive need was 8.9% (n = 213) for definition 1 and 9.6% (n = 218) for definition 2 and increased with age (Fig. 1). The prevalence of unmet refractive need (both definitions) was greatest for those ≥80 years old and lowest for those 50 to 59 years of age (P < 0.0001). Of interest, 45 (21%) of the 213 participants with unmet need (definition 1) and 39 (18%) of the 218 participants with unmet need (definition 2) had glasses or contact lenses.

Univariate Associations for Specific Risk Indicators

Frequency distributions and unadjusted and age-adjusted univariate analysis of risk indicators for uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need are presented in Table 2. Statistically significant age-adjusted indicators for uncorrected refractive error (in decreasing order of association, all P < 0.05) included $20,000 to $40,000 annual household income (odds ratio [OR], 1.46), being unemployed (OR, 1.45), never being married (OR, 1.44), lack of health insurance (OR, 1.39), lack of vision insurance (OR, 1.33), low acculturation scores (OR, 1.32), less than high school education (OR, 1.30), no eye examination within the past 12 months (OR, 1.28), and birth-place outside the United States (OR, 1.27). Moreover, compared with normal/underweight participants, obese (OR, 0.79) and overweight (OR, 0.68) participants were significantly less likely to have uncorrected refractive error.

TABLE 2.

Risk Indicators for Uncorrected Refractive Error and Unmet Refractive Need among LALES Participants (n = 6129)

| A. Frequency Distribution and Univariate Associations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥2 Lines Improvement (n = 926) | Unmet Refractive Need: Definition 1 (n = 213) | Unmet Refractive Need: Definition 2 (n = 218) | ||||

| Risk Factor | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) |

| Country of birth | ||||||

| United States | 198 (13.5) | 1 | 49 (6.4) | 1 | 46 (6.4) | 1 |

| Other | 728 (15.6) | 1.19 (1.01–1.41) | 164 (10.0) | 1.64 (1.18–2.29) | 172 (11.1) | 1.83 (1.31–2.57) |

| Acculturation score | ||||||

| >1.9 | 265 (13.0) | 1 | 61 (6.1) | 1 | 59 (6.2) | 1 |

| ≤1.9 | 661 (16.2) | 1.30 (1.11–1.51) | 152 (10.9) | 1.90 (1.39–2.59) | 159 (12.1) | 2.09 (1.53–2.86) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married + live w/partner | 629 (14.2) | 1 | 121 (7.3) | 1 | 127 (8.1) | 1 |

| Never married | 68 (18.1) | 1.33 (1.01–1.76) | 17 (11.7) | 1.68 (0.98–2.87) | 14 (10.7) | 1.36 (0.76–2.44) |

| Widowed | 106 (18.9) | 1.40 (1.12–1.76) | 49 (15.9) | 2.38 (1.67–3.40) | 50 (17.3) | 2.38 (1.67–3.40) |

| Separated/divorced | 123 (16.4) | 1.19 (0.96–1.47) | 26 (8.8) | 1.22 (0.78–1.90) | 27 (9.7) | 1.23 (0.79–1.89) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 357 (12.0) | 1 | 59 (6.1) | 1 | 62 (6.6) | 1 |

| Retired | 172 (18.6) | 1.685 (1.38–2.06) | 68 (11.7) | 2.06 (1.43–2.97) | 65 (11.9) | 1.92 (1.33–2.77) |

| Not working | 394 (18.1) | 1.604 (1.37–1.87) | 86 (10.2) | 1.77 (1.25–2.50) | 91 (11.5) | 1.85 (1.32–2.59) |

| Education (y) | ||||||

| ≥12 | 251 (12.3) | 1 | 41 (4.7) | 1 | 40 (4.8) | 1 |

| <12 | 674 (16.5) | 1.41 (1.20–1.64) | 171 (11.2) | 2.57 (1.81–3.66) | 178 (12.3) | 2.77 (1.94–3.95) |

| Income level ($US) | ||||||

| >40,000 | 83 (11.1) | 1 | 9 (2.7) | 1 | 10 (3.1) | 1 |

| 20,000–40,000 | 236 (12.8) | 1.18 (0.90–1.54) | 55 (7.9) | 3.07 (1.50–6.28) | 51 (7.7) | 2.56 (1.28–5.12) |

| <20,000 | 465 (16.8) | 1.63 (1.27–2.09) | 120 (11.2) | 4.53 (2.27–9.02) | 126 (12.5) | 4.39 (2.28–8.48) |

| BMI | ||||||

| Normal/underweight | 129 (18.8) | 1 | 44 (15.3) | 1 | 47 (17.7) | 1 |

| Overweight | 313 (13.5) | 0.67 (0.54–0.84) | 70 (8.1) | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 66 (8.1) | 0.41 (0.27–0.61) |

| Obese | 468 (15.4) | 0.79 (0.64–0.98) | 93 (7.6) | 0.46 (0.31–0.67) | 98 (8.4) | 0.43 (0.29–0.63) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 571 (15.2) | 1 | 126 (8.6) | 1 | 127 (9.2) | 1 |

| Ex-smoker | 223 (14.9) | 0.98 (0.83–1.16) | 51 (8.1) | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | 56 (9.5) | 1.04 (0.75–1.45) |

| Current smoker | 130 (15.4) | 1.105 (0.83–1.25) | 35 (11.7) | 1.398 (0.940–2.080) | 35 (12.2) | 1.38 (0.93–2.06) |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 554 (14.0) | 1 | 126 (7.1) | 1 | 124 (7.4) | 1 |

| No | 372 (17.3) | 1.28 (1.11–1.48) | 87 (13.9) | 2.11 (1.58–2.83) | 94 (15.9) | 2.38 (1.79–3.17) |

| Vision care insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 429 (13.9) | 1 | 97 (6.8) | 1 | 94 (7.0) | 1 |

| No | 490 (16.5) | 1.23 (1.07–1.41) | 114 (11.9) | 1.84 (1.38–2.44) | 121 (13.3) | 2.05 (1.54–2.72) |

| Health visit in past 12 months | ||||||

| Yes | 740 (15.0) | 1 | 176 (8.5) | 1 | 182 (9.2) | 1 |

| No | 186 (15.9) | 1.08 (0.90–1.28) | 37 (11.5) | 1.41 (0.97–2.05) | 36 (11.8) | 1.31 (0.90–1.9) |

| Eye exam in past 12 months | ||||||

| Yes | 140 (14.0) | 1 | 35 (5.9) | 1 | 38 (6.7) | 1 |

| No | 652 (15.3) | 1.12 (0.92–1.36) | 142 (9.3) | 1.64 (1.12–2.40) | 144 (10.1) | 1.56 (1.08–2.26) |

| B. Age-Adjusted Univariate Associations | ||||||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Factor | ≥2 Lines Improvement | Unmet Refractive Need Definition 1 | Unmet Refractive Need Definition 2 | |||

| Country of birth | ||||||

| US | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Outside of US | 1.27 (1.07–1.51)† | 1.89 (1.34–2.67)‡ | 2.09 (1.48–2.97)‡ | |||

| Acculturation score | ||||||

| >1.9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≤1.9 | 1.32 (1.13–1.54)‡ | 2.03 (1.48–2.78)‡ | 2.21 (1.61–3.04)‡ | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Never married | 1.44 (1.09–1.90)* | 1.76 (1.02–3.04)† | 1.42 (0.79–2.56) | |||

| Widowed | 1.10 (0.86–1.40) | 1.83 (1.24–2.70)† | 1.82 (1.24–2.69)* | |||

| Separated/divorced | 1.17 (0.95–1.45) | 1.22 (0.78–1.91) | 1.21 (0.78–1.87) | |||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Retired | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 1.58 (0.96–2.59) | 1.33 (0.81–2.18) | |||

| Unemployed | 1.45 (1.23–1.70)‡ | 1.64 (1.14–2.36)* | 1.66 (1.16–2.38)* | |||

| Education (y) | ||||||

| ≥12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| <12 | 1.30 (1.11–1.52)† | 2.46 (1.72–3.52)‡ | 2.63 (1.84–3.77)‡ | |||

| Annual income level ($US) | ||||||

| >40,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 20,000–40,000 | 1.46 (1.13–1.87)† | 3.01 (1.47–6.20)‡ | 2.27 (1.35–3.82)‡ | |||

| <20,000 | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 4.32 (2.14–8.70)‡ | 4.26 (2.18–8.31)‡ | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| Normal/underweight | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Overweight | 0.68 (0.54–0.85)† | 0.54 (0.36–0.81)† | 0.44 (0.30–0.67)‡ | |||

| Obese | 0.79 (0.64–0.98)† | 0.52 (0.35–0.78)† | 0.49 (0.33–0.72)‡ | |||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ex-smoker | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 0.92 (0.66–1.31) | 1.02 (0.73–1.42) | |||

| Current smoker | 1.06 (0.86–1.31) | 1.50 (1.00–2.24) | 1.47 (0.98–2.20) | |||

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| No | 1.39 (1.20–1.61)‡ | 2.74 (2.00–3.75)‡ | 3.03 (2.22–4.12)‡ | |||

| Vision insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| No | 1.33 (1.15–1.54)‡ | 2.19 (1.63–2.96)‡ | 2.43 (1.81–3.28)‡ | |||

| Health visit in past 12 months | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| No | 1.18 (0.99–1.41) | 1.54 (1.05–2.25)* | 1.41 (0.96–2.07) | |||

| Eye exam in past 12 months | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.28 (1.05–1.57)* | 1.78 (1.20–2.60)† | 1.70 (1.17–2.48)† | |||

Definitions 1 and 2 are as in Table 1. Significant associations are in bold.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

The unadjusted and age-adjusted univariate analysis of risk indicators for both definitions of unmet refractive need is also displayed in Table 2. Statistically significant age-adjusted indicators for unmet refractive need definition 1 (in decreasing order of association, all P < 0.05) included <$20,000 annual income (OR, 4.32), $20,000 to $40,000 annual income (OR, 3.01), no health insurance (OR, 2.74), <12 years of education (OR, 2.46), no vision insurance (OR, 2.19), ≤1.9 acculturation scores (OR, 2.03), country of birth outside the United States (OR, 1.89), widowed marital status (OR, 1.83), no eye examination within the past 12 months (OR, 1.78), never-married status (OR, 1.76), unemployment status (OR, 1.64), and no health visit in the past 12 months (OR, 1.54). Obese (OR, 0.52) and overweight (OR, 0.54) participants were significantly less likely to exhibit unmet refractive need definition 1.

The statistically significant age-adjusted indicators for unmet refractive need definition 2 (in decreasing order of association, all P < 0.05) included <$20,000 annual income (OR, 4.26), no health insurance (OR, 3.03), <12 years of education (OR, 2.63), no vision insurance (OR, 2.43), $20,000 to $40,000 annual income (OR, 2.27), ≤1.9 acculturation scores (OR, 2.21), country of birth outside the United States (OR, 2.09), widowed marital status (OR, 1.82), no eye examination within the past 12 months (OR, 1.70), and unemployment status (OR, 1.66). Like uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need definition 1, obese (OR, 0.49) and overweight (OR, 0.44) participants were significantly less likely to exhibit unmet refractive need definition 2.

Unmet refractive need for definitions 1 and 2 appeared to have similar significant risk indicators. Among all factors, annual income <$20,000 was the strongest risk indicator for both unmet refractive need definitions 1 (OR, 4.32) and 2 (OR, 4.26). Overweight and obese participants were less likely to have uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need.

Independent Risk Indicators for Uncorrected Refractive Error and Unmet Refractive Need

Table 3 presents the results of the stepwise logistic regression analysis identifying independent risk indicators associated with uncorrected refractive error. The independent risk indicators in order of importance (indicated in the heading for each risk indicator in Table 3) were age, health insurance, education, BMI, and employment status. Reported ORs for each independent risk indicator were adjusted for all other risk indicators by multivariate logistic regression. After adjustment for health insurance, education, BMI, and employment, age was significantly associated with an improvement in vision after refraction in all age groups, with ORs ranging from 1.53 in 50- to 59-year-olds to 2.19 in ≥80-year-olds. ORs for the other significant risk indicators that emerged (in decreasing order of association from the multivariate logistic regression approach, all P < 0.05) were <12 years of education (OR, 1.35), no health insurance (OR, 1.34), and unemployed work status (OR, 1.29). Overweight participants were less likely to exhibit uncorrected refractive error (OR, 0.69).

TABLE 3.

Stepwise and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk Indicators for Uncorrected Refractive Error and Unmet Refractive Need among LALES Participants

| Factor | ≥2 Lines Improvement (n = 4526) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) Unmet Refractive Need Definition 1 (n = 1807) |

Unmet Refractive Need Definition 2 (n = 1709) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 40–49 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–59 | 1.53 (1.24–1.90) ‡ | 0.56 (0.34–0.93) ‡ | 0.54 (0.33–0.90) ‡ |

| 60–69 | 2.07 (1.61–2.67) ‡ | 0.80 (0.49–1.32) | 0.80 (0.49–1.31) |

| 70–79 | 1.81 (1.26–2.62) ‡ | 1.18 (0.67–2.08) | 1.09 (0.61–1.92) |

| ≥80 | 2.19 (1.25–3.84) ‡ | 2.98 (1.38–6.44) ‡ | 2.79 (1.28–6.09) ‡ |

| Employment Status | 5 | — | — |

| Employed | 1 | — | — |

| Retired | 1.20 (0.88–1.63) | — | — |

| Unemployed | 1.29 (1.06–1.56) * | — | — |

| Education (y) | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <12 | 1.35 (1.12–1.64) † | 2.46 (1.57–3.86) ‡ | 2.56 (1.63–4.02) ‡ |

| Annual Income Level | — | 5 | 5 |

| >$40,000 | — | 1 | 1 |

| $20,000–$40,000 | — | 2.32 (1.07–5.05)* | 2.06 (0.94–4.53) |

| <$20,000 | — | 2.62 (1.22–5.62) * | 2.80 (1.30–6.02) * |

| BMI | 4 | — | 4 |

| Normal/underweight | 1 | — | 1 |

| Overweight | 0.69 (0.52–0.90) * | — | 0.48 (0.29–0.80) * |

| Obese | 0.83 (0.64–1.07) | — | 0.59 (0.37–0.94) * |

| Smoking status | — | 4 | 6 |

| Nonsmoker | — | 1 | 1 |

| Ex-smoker | — | 1.11 (0.73–1.67) | 1.27 (0.84–1.91) |

| Current smoker | — | 1.82 (1.14–2.91) * | 1.79 (1.11–2.88) * |

| Health insurance | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1.34 (1.12–1.61) † | 2.11 (1.44–3.09) ‡ | 2.26 (1.54–3.30) ‡ |

All significant associations are in bold. Also, the order of significance for each risk indicator (from the stepwise logistic regression analyses) is indicated in bold in the heading for each outcome variable.

Definitions 1 and 2 are as in Table 1.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

In addition, Table 3 presents the stepwise analyses for unmet refractive need. For definition 1, the independent risk indicators in order of importance (indicated in the heading for each risk indicator in Table 3) were education, health insurance, age, smoking status, and annual income level. The multivariate analyses showed that the association varied across the age categories, with ≥80 years of age being the only significant age risk (OR, 2.98). ORs for the other significant risk indicators that emerged (in decreasing order of association from the multivariate logistic regression approach, all P < 0.05) included <$20,000 annual income (OR, 2.62), <12 years of education (OR, 2.46), $20,000 to $40,000 annual income (OR, 2.32), no health insurance (OR, 2.11), and current smoker (OR, 1.82). The younger age group (50–59 years) was less likely to have unmet refractive need definition 1 (OR, 0.56).

For unmet refractive need definition 2, the independent risk indicators were similar to those for definition 1. The order of importance was education, health insurance, age, BMI, annual income level, and smoking status. The multivariate analyses showed that ≥80 years of age was also the only significant age risk (OR, 2.79). Other risk indicators that emerged (in decreasing order of association from the multivariate logistic regression, all P < 0.05) included <$20,000 annual income (OR, 2.80), <12 years of education (OR, 2.56), no health insurance (OR, 2.26), and current smoker (OR, 1.79). Last, overweight and obese participants were again less likely to exhibit unmet refractive need (definition 2: OR, 0.48 and OR, 0.59, respectively). Participants aged 50 to 59 were again less likely to have unmet refractive need definition 2 (OR, 0.54).

In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, age of ≥80 years was the strongest risk indicator for both uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need, followed by low annual income, short duration of education, no health insurance, and unemployed status. Overweight and obesity consistently appeared to be the protective factors for both uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need.

DISCUSSION

Uncorrected Refractive Error

Although the current data on uncorrected refractive error in general are limited, data are even sparser for Latinos, a rapidly expanding population. In our sample of 6129 Los Angeles Latinos aged 40 years and older, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was 15.1%. Previous population-based studies including the Baltimore Eye Study, Visual Impairment Project, Blue Mountains Eye Study, Proyecto VER studies, and Bangladesh Low Vision Survey also conducted estimates of uncorrected refractive error prevalence in various racial/ethnic groups. To highlight the differences and similarities among groups and with LALES, we compared the study designs including sample size, ethnicity, uncorrected refractive error prevalence and risk indicators in Table 4.12,21–24 However, because the definitions for uncorrected refractive error were not consistent among studies, we recalculated our estimates for LALES to match the specific criteria presented in these four studies listed in Table 4. It is important to note that, primary raw data were not used to calculate these comparison prevalence estimates. Compared with the uncorrected refractive error prevalence from other population-based studies, Latinos had a higher rate than African Americans from the Baltimore Eye Study, Caucasians from the Visual Impairment Project, and Southeast Asians from the Bangladesh Low Vision Survey.22–24 These data underscore the importance of refractive error correction as an important intervention to decrease the burden of visual impairment.12,21,24–26

TABLE 4.

A Comparison of Uncorrected Refractive Error among Population-Based Studies

| Study | Sample Size | Ethnicity of Study Population | Study-Specific Definition of Uncorrected Refractive Error | Uncorrected Refractive Error (%) | LALES Uncorrected Refractive Error (%) | Other Risk Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore Eye Survey24 | 2389 | African American | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) <20/40 presenting visual acuity in better eye | 55.2 | 62.5 | Increased risk: older age. |

| Baltimore Eye Survey24 | 2911 | Caucasian | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) <20/40 presenting visual acuity in better eye | 66.2 | Increased risk: older age. | |

| Blue Mountains Eye Study21 | 3654 | Caucasian | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) ≥10 letter improvement <20/30 presenting visual acuity in better eye | 45.6 | 47.8 | Increased risk: older age, hyperopia, longer interval from last eye examination, tradesperson, laborer, receipt of government pension, living alone. |

| Visual Impairment Project22 | 4735 | Caucasian | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) ≥5 letter improvement <20/20 minus 2 letters presenting visual acuity in better eye | 57.0 | 77.8 | Increased risk: older age, absence of distance refractive correction, presence of cataract, European or Middle Eastern language spoken at home, education level, time of last eye examination. |

| Protective: rural test location, tertiary education, hypermetropia. | ||||||

| Proyecto VER12 | 4774 | Mexican- Americans | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) ≥2-line improvement <20/40 presenting visual acuity in better eye | 77 | 65.5 | Increased risk: older age, <13 years of education, low acculturation index, no insurance, no eye exam in past 2 years. |

| Bangladesh Low Vision Survey*23 | 11624 | East Asian | (Best corrected VA – presenting VA) <20/40 presenting visual acuity in better eye | 51.1 | 62.5 | Increased risk: female gender, old age, rural residence, unemployed, retired, manual workers, illiteracy. |

This study did not report specific data on uncorrected refractive error, and the prevalence estimate presented was calculated based on the visual acuity data published in the cited article.

Other than the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES), only one other population-based study, Proyecto VER, has provided data on the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error. In Proyecto VER, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error was 77%, slightly higher than the 65.5% in LALES. The results from both groups confirmed a high prevalence of uncorrected refractive error in American Latinos and further emphasize the need for refractive correction in this minority group.12 Despite high rates of uncorrected refractive error in both populations, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error in LALES was lower than that of Proyecto VER. One may have hypothesized that the difference between the data in the two population-based studies could be from the fact that on average, LALES participants were younger than Proyecto VER participants (12% of LALES participants vs. 17.3% of Proyecto VER participants were 70 years of age and older and compared with LALES, Proyecto VER had twice the proportion of individuals 80 years of age and older). However, after age-adjusted direct standardization by using the age distribution from Proyecto VER, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error decreased from 65.5% to 61.6%. This finding suggests that Latinos in Los Angeles are more likely to have refractive correction than those in Arizona, possibly due to better access to resources and transportation systems than in Arizona.

The independent risk indicators analysis for uncorrected refractive error highlighted that age was the strongest risk indicator in this population followed by no health insurance, low education, and unemployed status. Of interest, age, low education, and a lack of insurance coverage were important risk indicators in Proyecto VER as well.12 Our findings pertaining to age and lower education are also similar to those noted in Australia in the Blue Mountain Eye Study and the Visual Impairment Project.21,22 The striking similarities in these risk indicators across racial/ethnic groups and in different countries underscores the importance of public education and healthcare access, particularly for refractive correction in the population.

Unmet Refractive Need

Our unmet refractive need definition 1 comparison was derived from Bourne et al.19 The LALES unmet refractive need was similar to that in Bangladesh (8.9% vs. 7.9%). This difference can partially be accounted for by the different age distributions. Although LALES included subjects older than 40 years, Bangladeshi included subjects older than 30 years. In LALES, the unmet refractive need also increased with age; therefore, it is reasonable to obtain a slightly higher unmet refractive need rate with a slightly older population. In addition, Bourne et al. in the Bangladeshi study excluded all persons who had an uncorrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better in the better eye, on the assumption that these subjects probably did not need distance refractive correction. Although the reasoning for this criterion is well founded, this design may miss subjects who would nevertheless benefit from visual refraction. The difference may also be partially attributable to the difference in life expectancy in these two groups. In Bangladesh, life expectancy is 63 years for both men and women, whereas Latinos in LA county have a higher life expectancy (82.5 years).27,28 Because unmet refractive need increased with age in LALES, it is not surprising to find a longer life expectancy leading to a higher unmet refractive need. The longer life expectancy of Latinos in Los Angeles County may be due to genetic protective factors, cultural differences, strong family ties, and faith.

The unmet refractive need prevalence in LALES was not just higher than that of the rural population of Bangladesh, but also the urban population in Tehran. Fotouhi et al.29 conducted a population-based study on the unmet refractive need in Tehran, and the prevalence was 4.8% as opposed to 8.9% in LALES. The unmet refractive need in LALES was clearly higher than that of the Tehran group, a finding that could be attributed in part to differences in study design. In the Tehran group, mean age was younger than that of the LALES (31.4 vs. 54.9) and unmet refractive need rates were lower in younger participants. Of interest, Tehrani subjects older than 46 years had a higher unmet rate than did the same age group in LALES, suggesting a higher prevalence of unmet refractive need among the elderly in Tehran.

Our unmet refractive need definition 1 results were echoed by those in a study conducted by Vitale et al.,3 who studied the prevalence of visual impairment in the United States based on the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I). Although the prevalence of unmet refractive need definition 1 was high for LALES participants in Los Angeles, the national prevalence rate for Hispanics was even higher (8.9 vs. 9.2). Although this difference could be partially attributed to the difference in study designs such as different participant age groups, this finding may still suggest that Mexican Americans in Los Angeles have better access to care than Latinos in Arizona, as mentioned previously, or than Hispanics in the rest of the country.

Similar to our results, Vitale et al.3 found that Hispanics had the highest unmet refractive need among all ethnic groups in the United States; the rate for Hispanics was 2.3% higher than for African Americans and 5.1% higher than for Caucasians. This finding identified Latinos as the ethnic group most at risk nationwide. Furthermore, many risk indicators such as Hispanic ethnicity, low income level, lack of health insurance, and low level of education were shared in both studies, which identified this problem on a national level and once again emphasized the importance of improving healthcare access and resources for this minority group in the United States.

We have developed a second definition of unmet refractive need because, based on previous LALES data, a 2-line improvement in visual acuity was associated with a significant increase in vision-related quality of life.30 The slight increase in prevalence between definitions 1 and 2 (8.9% and 9.6%, respectively) suggests that more people will experience an improved quality of life if refractive error is corrected based on the more flexible unmet refractive need definition criteria. The prevalence of unmet refractive need was consistently higher in both sex groups and all age groups when definition 2 was applied, signifying its higher sensitivity in identifying people who may benefit from refraction. Definition 2 may be superior to definition 1 because it also includes subjects who, despite an improvement of two or more lines after refraction, still could not reach a corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better. In essence, definition 2 identified subjects with worse presenting or best corrected visual acuity who could nevertheless benefit from refraction than the ones identified by definition 1.

The top four independent risk indicators for unmet refractive need (both definitions) were age, <12 years of education, <$20,000 income, and a lack of health insurance. For definition 1, the Bangladesh Low Vision Survey noted similar findings for low education.19 As for the unmet refractive need risk indicators analyses, there is a paucity of published resources for comparison thus far. However, it is likely that low income and lower education are related to lack of access to care. In a vicious cycle, it is likely that poor vision can lead to poor performance at school or work, which may again lead to low education and low income levels.

The protective association noted among obese and over-weight individuals was unexpected and difficult to explain. One explanation is that perhaps obesity and its related symptoms made the subjects more aware of their medical problems and health issues in general, prompting more frequent health-care provider visits and higher refractive correction rate. When further evaluating this group of LALES participants, we found that among the participants with uncorrected refractive error that were obese or overweight, 28% had diabetes, whereas only 9% of the normal-weight group had diabetes. Of the participants with diabetes, 24% had had a complete eye examination in the past 12 months, compared with 15% of the participants without diabetes (P < 0.05). Thus, there was a higher prevalence of obese/overweight participants having eye examinations; hence, obesity/overweight could be regarded as protective.

In addition to unmet refractive need, we evaluated spectacle coverage in our LALES population. The spectacle coverage for LALES participants was 21.1%, applying the definition of spectacle coverage published by Bourne et al.19 Our findings are similar to the 25.2% noted by the Bangladesh Low Vision Survey group. Similar to unmet refractive need, our LALES findings for spectacle coverage again suggest that Latinos in the Los Angeles have access to eye care services similar to that of Bangladeshi adults despite the striking difference in per capita income between Latinos in Los Angeles ($12,464) and Bangladeshis ($476). In addition, a large number of participants in both of these studies were not wearing the proper vision correction; therefore, strategies should be developed that do not provide spectacle coverage at just one time point, but perhaps can monitor changes in refractive need over time and provide the needed refractive correction. Surprisingly, in contrast to Bangladesh and Los Angeles, the spectacle coverage was 66% in Tehran.29 Despite differences in age distributions of the populations among three studies, a higher spectacle coverage rate in Tehran highlights the problems with the provision of refractive correction and by extension the vision care system in the United States.

While the LALES has a large sample size and used standardized methodology, a possible bias may arise from a higher participation of women and younger Latinos. Nevertheless, no differences were noted between the women and the men, and thus the higher participation rate of women is unlikely to impact the overall prevalence of uncorrected refractive error or refractive need. On the other hand, since the participation rate in older Latinos was slightly lower than that of younger Latinos and since older Latinos have a higher prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and unmet refractive need, our estimates are likely to be a relative underestimate of the problem. However, because the overall and age-specific nonparticipation rates were low, we do not believe that this would have substantially affected our estimates. In addition, the findings from our study population were primarily applicable to Latinos of Mexican American descent, and therefore these data cannot be applied to all Latino Americans. Last, recent studies in India and Tanzania31,32 highlight that problems with near vision represent a major, often unmet, refractive need among older persons. One limitation of our study is that we did not collect detailed near-vision data to evaluate this need in our population.

Overall, many of the negative health outcomes for this Latino community are inherent in the apparent lack of access to eye healthcare services. While poor vision health is related to a lack in health and vision insurance, it is also related to low education levels within this community. Although acculturation did not emerge as a risk indicator in the multivariate analyses (as it was collinear with lower levels of education and lack of health insurance), it is important to note that these less acculturated individuals have far more difficulty in seeking out healthcare because of language problems or lack of knowledge about available resources. Further, less educated individuals have increased difficulty navigating within the healthcare system, and perhaps the current public health messages are not fully comprehended by them. In addition, they may hold a very different belief system about healthcare from the mainstream such as the assumption that poor vision is part of the natural aging process irremediable by medical measures, which prevents them from seeking help. Finally, particularly in Los Angeles, a lack of easy access to public transportation may also factor in the lack of access to health and vision care. One approach to this problem may consider the provision of (1) education regarding the value of refractive correction and availability of refractive services within the community and (2) good-quality, affordable refractive correction in the community. Each facet of this two-pronged intervention is more likely to occur if community, local, state, and federal agencies participate and provide the infrastructure and manpower for such interventions.

In conclusion, our population-based study confirmed the high prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and is the first study to document the magnitude of unmet refractive need in a population-based sample of Latinos who are primarily Mexican-American. Our data suggest that given the relatively easy intervention of refraction and provision of refractive correction, it is possible to reduce visual impairment significantly and potentially improve quality of life in this fastest growing segment of the U.S. population. Furthermore, this problem is likely to grow, given the aging and increased life expectancy of the population. Thus, it is incumbent on health policy planners, service organizations, and eye care providers to develop cost-effective interventions that target this population.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Eye Institute and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Eye Institute Grants EY11753 and EY03040, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY. RV is a Research to Prevent Blindness Sybil B. Harrington Scholar.

Footnotes

Disclosure: R. Varma, None; M.Y. Wang, None; M. Ying-Lai, None; J. Donofrio, None; S.P. Azen, None

References

- 1.Prevent Blindness America. Vision Problems in the U.S.: Prevalence of adult vision impairment and age related eye disease in America 2002. [Accessed June 12, 2007]; Available at www.preventblindness.org/vpus/VPUS_report_web.pdf.

- 2.World Health Organization. [Accessed June 12, 2007];Blindness: magnitude and causes of visual impairment. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs282/en/index.html.

- 3.Vitale S, Cotch MF, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2158–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandona R, Dandona L. Refractive error blindness. Bull World Health Org. 2001;79:237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varma R, Wu J, Chong K, Azen SP, Hays RD. Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Impact of severity and bilaterality of visual impairment on health-related quality of life. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(10):1846–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty CA, Nanjan MB, Taylor HR. Vision impairment predicts 5 year mortality. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(3):322–326. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Simpson JM, et al. Visual impairment, age-related cataract, and mortality. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(8):1186–1190. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, et al. Performance-based and self-assessed measures of visual function as related to history of falls, hip fractures, and measured gait time. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(1):160–164. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)91911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelhafiz AH, Austin CA. Visual factors should be assessed in older people presenting with falls or hip fracture. Age Ageing. 2003;32(1):26–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivers RQ, Nortaon R, Cumming RG, et al. Visual impairment and risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(7):633–639. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.7.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood RH. Visual problems and falls. Age Ageing. 2001;30 Suppl 4:13–18. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.suppl_4.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muñoz B, West SK, Rodriguez J, et al. Blindness, visual impairment and the problem of uncorrected refractive error in a Mexican-American population: Proyecto VER. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(3):608–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau: 2006 American Community Survey. Selected population profile. [Accessed October 16, 2007];Hispanic or Latino (of any race) Available at http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/IPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201PR&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201T&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201TPR&-reg=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201:400;ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201PR:400;ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201T:400;ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201TPR: 400&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=en&-format=

- 14.Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Klein R, Azen SP Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Prevalence and risk indicators of visual impairment and blindness in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1132–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varma R, Paz S, Azen S, et al. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study: design, methods and baseline data. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuellar I, Harris LC, Jasso R. An acculturation scale for Mexican American normal and clinical populations. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1980;2:199–217. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, et al. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HHANES 1982–84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80 suppl:11–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferris FL, III, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, et al. New visual acuity charts for clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourne R, Dineen BP, Huq DM, et al. Correction of refractive error in the adult population of Bangladesh: meeting the unmet need. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(2):410–417. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charman WN. Visual standards for driving. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1985;5(2):211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiagalingam S, Cumming RG, Mitchell P. Factors associated with undercorrected refractive errors in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmology. 2002;86(9):1041–1045. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liou H, McCarty CA, Jin CL, et al. Prevalence and predictors of undercorrected refractive errors in the Victorian population. Am J Ophthalmology. 1999;127(5):590–596. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dineen BP, Bourne RRA, Ali SM, et al. Prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(7):820–828. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.7.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Witt K, et al. The Baltimore Eye Survey Research Group. Blindness and visual impairment in an American urban population. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(2):286–290. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040138048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, et al. Baltimore Eye Survey Research Group. Socioeconomic status and visual impairment among urban Americans. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(5):637–641. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080050051027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attebo K, Mitchell P, Smith W. Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(3):357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30684-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. [Accessed June 12, 2007];Countries. Bangladeshi. Available at http://www.who.int/countries/bgd/en/

- 28.Pitkin B, Iya Kahramanian M, Richardson E, et al. Latino Scorecard 2006. Los Angeles, CA: United Way of Greater Los Angeles; 2006. pp. 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Raissi B, et al. Uncorrected refractive errors and spectacle utilisation rate in Tehran: the unmet need. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(5):534–537. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.088344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Globe DR, Wu J, Azen SP, Varma R Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. The impact of visual impairment on self-reported visual functioning in Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1141–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nirmalan PK, Krishnaiah S, Shamanna BR, Rao GN, Thomas R. A population-based assessment of presbyopia in the state of Andhra Pradesh, south India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(6):2324–2328. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke AG, Patel I, Munoz B, et al. Population-based study of presbyopia in rural Tanzania. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(5):723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]