Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that allelic variation in 5HTT gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) genotype was associated with sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) as a main effect and as moderated by the chronic stress of caregiving. Serotonin (5HT) is involved in sleep regulation and the 5HT transporter (5HTT) regulates 5HT function. A common 44-base pair deletion (s allele) polymorphism in the 5-HTTLPR is associated with reduced 5HTT transcription efficiency and 5HT uptake in vitro.

Methods

Subjects were 142 adult primary caregivers for a spouse or parent with dementia and 146 noncaregiver controls. Subjects underwent genotyping and completed the PSQI.

Results

Variation in 5-HTTLPR genotype was not related to sleep quality as a main effect (p >.36). However, there was a caregiver X 5-HTTLPR interaction (p < .009), such that the s allele was associated with poorer sleep quality in caregivers as compared with controls.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that the s allele may moderate sleep disturbance in response to chronic stress.

Keywords: 5-HTTLPR, serotonin transporter promoter gene polymorphism, sleep quality, gene-environment interaction, stress

INTRODUCTION

Prior research has documented the involvement of central nervous system (CNS) serotonin (5HT) in sleep regulation (1,2). In general, and although the underlying mechanisms are not completely understood, increased activity of serotonin neurons is associated with wakefulness (3,4). Increased 5HT2 receptor stimulation has also been shown to reduce slow wave sleep (1). The 5HT transporter (5HTT) is an important regulator of 5HT function, and inhibition of 5HTT function by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is generally associated with poorer sleep quality and specifically less rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (3,5). A common 44-base pair deletion (s allele) polymorphism in the 5HTT gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) has been associated with reduced 5HTT transcription efficiency and reduced 5HT uptake in vitro (6). Multiple behavioral and physiological phenotypes have now been associated with 5-HTTLPR genotypes (6–8). Although 5-HTTLPR genotype does not consistently predict transporter expression in the brain (9,10), 5-HTTLPR genotypes have been associated with altered CNS 5HT function as indexed by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 5HIAA or prolactin response to citalopram (8,11). To our knowledge, however, there have been no reports of associations between 5-HTTLPR genotypes and sleep measures.

Health researchers are becoming increasingly aware that risk factors do not act in isolation and it is therefore important to consider their joint impact. Relevant to the current work, it has also been shown that the effects of genetic risk factors on outcomes may be significantly modified by environmental exposures (12). This suggests that, in some circumstances, the influence of allelic variation may only manifest in the presence of stressful environmental conditions. Some evidence indicates that this is specifically true of vulnerability to sleep disturbance in response to stress, which seems to have trait-like stability in individuals across different stressors and over time (13–16). We, and others, have previously reported (17,18) that caregivers have poorer sleep quality as compared with noncaregiving controls. Because both the stress of care-giving and increased stimulation of CNS 5HT neurons have been shown to influence sleep, we examined the effects of the 5-HTTLPR genotype on sleep quality as moderated by a major life stressor—caregiving for a close relative with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia.

Based on the foregoing observations, we hypothesized that the 5-HTTLPR s allele would be associated with poorer sleep quality. In addition, based on research suggesting that stress may significantly modify the effects of genes on outcomes (12), we hypothesized that the effects of 5-HTTLPR allelic variation would be magnified by the stress of caregiving.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

Participants were recruited to be part of a study designed to examine the underlying genetic, biological, and behavioral mechanisms whereby stressful social and physical environments lead to health disparities. The present study was conducted at Duke University Medical Center. Data were gathered from May 16, 2001 through June 3, 2004. Caregivers were recruited using flyers, ads in the local media, and outreach efforts conducted under the auspices of a Community Outreach and Education Program. Controls were identified by asking each caregiver to nominate two to five friends who live in their neighborhood and are like them with respect to key demographic factors (e.g., race, gender). All subjects gave informed consent before their participation in the study. Subjects enrolled in the study received $250 for their participation. Individuals who were experiencing any acute major medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study, resulting in the exclusion of one individual who experienced a severe psychiatric problem. Data were collected in two venues—a questionnaire battery was given to participants during a home visit by a nurse and returned on their visit to the General Clinical Research Center at Duke University Medical Center. The home assessment was scheduled during the same week as the physical examination. Home visits took place in the afternoon and clinic visits were held between 8 AM and 10 AM. During the clinic visit, participants received a general physical examination and blood samples were drawn to assess biological parameters. Informed consent was obtained using a form approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The original study sample consisted of 344 participants; 175 adults who reported significant caregiving responsibility for a relative (primarily parent) or a spouse diagnosed with dementia; and 169 controls did not have caregiving responsibilities. A total of 17 individuals did not have valid data for 5-HTTLPR, resulting in 327 participants who had complete data for each of the primary constructs. In addition, homozygosity for the long variant of the 5-HTTLPR has been associated with increased night-time motor activity during treatment with an SSRI (19) and antidepressants can significantly interfere with various aspects of sleep (20). Therefore, we excluded 39 participants who reported current use of an antidepressant prescribed by a physician. The final sample consisted of 288 participants (142 caregivers and 146 noncaregiver controls); 30.0% were African American and 25.4% were male.

Measures

Sleep Quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (21) was used to measure sleep quality. The scale consists of 19 items that assess various aspects of sleep during the past month (e.g., time to fall asleep, aspects related to sleep disruption). The items on the scale are used to form the following seven component scores: overall sleep quality, sleep latency (time to fall asleep on going to bed), sleep duration, sleep efficiency (time asleep/time in bed × 100), sleep disturbances, problems with daytime functioning, and medications taken for sleep. The seven component scores may be summed to provide a global score (PSQI), with higher scores reflecting poorer sleep quality. A score of ≥5 on the global rating suggests moderate sleep problems in ≥3 areas, or more severe problems in at least two areas. Acceptable psychometric properties have been demonstrated with respect to internal homogeneity, test-retest reliability, and validity (21).

Genotyping

To determine 5-HTTLPR genotypes, genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted by standard procedure (Puregene D-50K Isolation Kit, Gentra, Minneapolis, Minnesota) from fresh or frozen samples of peripheral blood collected from the subjects. Polymerase chain reaction amplification to generate a 484- or 528-base pair fragment corresponding to the short (s) and long (l) 5-HTTLPR alleles, respectively, was performed (6) with the following modifications: 100 ng of genomic DNA was used in each reaction mixture; deoxyguanosine triphosphate was substituted for 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine triphosphate; and the final volume of each reaction mixture was 25 μl. The fragments were resolved by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gels.

Table 1 provides distributions for caregiver status broken down by allele frequency. The distribution of allele frequency was similar between caregivers and controls (p<.76). We tested for Hardy Weinberg Equlibrium (HWE) in the total population. The sample as a whole did deviate from HWE (p < .01). The frequency of the l allele in African Americans, as compared with Caucasians, likely accounted for the deviation. Confirming this notion is the fact that when we examined HWE within groups of African Americans and Caucasians, the results were consistent with HWE.

TABLE 1.

5-HTTLPR Allele Frequency Distributions by Caregiver Status

| Characteristic, n (%)a | S/S | S/L | L/L |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample, N = 288 | |||

| Caregivers, 142 (49.3%) | 28 (19.7%) | 62 (43.7%) | 52 (36.6%) |

| Controls, 146 (50.7%) | 34 (23.3%) | 61 (41.8%) | 51 (34.9%) |

Percentages in the Characteristics column are calculated from the total sample, by caregiver status; percentages in the remaining columns represent those for each row total.

Analytic Plan

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine the hypotheses that allelic variation in 5-HTTLPR is related to sleep quality, and that the effect will be moderated by the stressor of caregiving (caregiver versus control). The 5-HTTLPR genotype (i.e., a three-level categorical variable representing ll, ls, and ss genotype status) was modeled as a predictor of PSQI scores, and the overall genotype effect was evaluated using a 2 degree of freedom test. We also examined the interaction of caregiver group with 5-HTTLPR. Age in years, race (African American or Caucasian, based on self-report), and gender were included as covariates in all models. SAS V9 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used to conduct all analyses.

RESULTS

As reported in our prior findings (17), caregivers had significantly poorer sleep quality ratings, as compared with controls (p < .001: caregivers = 7.0 ± 3.7 (mean ± standard deviation); controls = 5.4 ± 3.4). The mean age in years for each group was: caregivers = 60.9 ± 13.9 and controls = 55.8 ± 14.9; p < .001. Age was not significantly related to PSQI scores (p < .06).

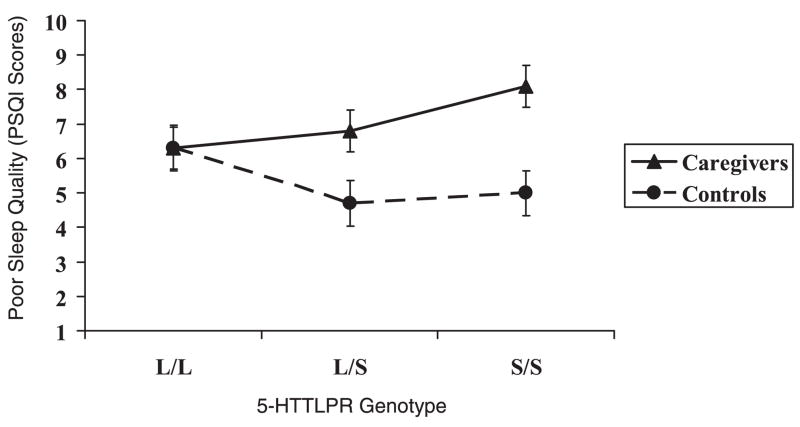

The two-way interaction of caregiver status × allele group was significant (p < .009), such that homozygosity for the s allele, in combination with the stress of caregiving, was associated with poorer sleep quality as compared with all remaining groups. Figure 1 depicts the adjusted means (SE) for sleep quality by caregiver and genotype status. The main effect of genotype on sleep quality was nonsignificant (p < .36).

Figure 1.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): Caregiver Stress × 5-HTTLPR genotypes (higher sleep quality scores = poorer sleep; values are adjusted means and error bars = standard errors).

We also examined effects of the caregiver status × genotype interaction term as predictors of the seven component scores of the PSQI. The interaction term was significantly associated with the component scores of latency (time to fall asleep on going to bed; p < .04) and sleep disturbances (p < .05); and marginally associated with sleep efficacy and problems with daytime functioning (p < .10). The form of the interactions for these measures was similar to the pattern found for the global PSQI scores, such that caregivers with the s/s allele had poorer sleep quality as compared with caregivers with the l allele and all noncaregivers.

DISCUSSION

Although we did not find a main effect of 5-HTTLPR genotype on sleep quality, these findings are consistent with our second hypothesis; i.e., effects the 5-HTTLPR s allele have on sleep quality would be magnified by the stress of caregiving. From the point of view of future research on genetic effects on health-related phenotypes, the present results provide preliminary evidence for the recently highlighted (12) importance of considering environmental exposures before concluding that there is no genetic effect on important phenotypes. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between 5-HTTLPR genotypes and sleep quality.

The hypothesized poorer sleep quality associated with the s allele was observed in the caregivers in the present study but not the controls. There are many potential explanations for this discordance, but one plausible scenario is that the increased stress experienced by the caregivers was associated with increased 5HT release whose effects on 5HT neurons was increased and/or prolonged by reduced 5HT reuptake associated with the s allele. There is ample evidence of such gene × environment interactions affecting depression in several human studies (22–24) and for rhesus macaques, which exhibited an association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and adrenocorticotropic hormone responses to stress after adverse early experience (25).

Regionally selective effects of 5HTT on serotonergic functions influencing sleep could also contribute to complex differences in sleep quality. Serotonin effects on sleep are complicated: centers in the pons decrease slow wave sleep through actions on 5HT2 receptors (1,26–28) and decrease paradoxical sleep through actions on 5HT1a receptors (29) whereas serotonin actions in the preoptic area may have opposite effects on sleep (29). Regionally selective effects of 5HTT on anxiety-related brain activation have been shown (30). Such effects, if they occur also in serotonin terminal fields that regulate sleep, could contribute to a population-specific relationship between chronic stress, serotonin physiology, and 5-HTTLPR genotype.

The results of this study suggest a relationship between a genetic polymorphism and the trait-like differential vulnerability to experience disturbed sleep in response to stressors (15,16). Further work is needed to determine whether the s allele represents a vulnerability factor for sleep disturbance under stress. As outlined in a recent review, there is a need to identify factors that account for individual differences in vulnerability to develop sleep difficulties in order to improve our understanding of these difficulties, and to improve clinical care, public health, and quality of life (14).

To better characterize the relationship between the s allele and stress-related vulnerability to develop sleep difficulties, it will be important to carry out studies that address some of the limitations of this study. It is unclear if the sleep disturbance experienced by the s allele caregivers is occurring in association with generalized stress or specific nocturnal disturbances, which lead to awakenings or prevent sleep. The PSQI subscale analysis indicates that the caregivers with the s allele were specifically vulnerable to the nocturnal sleep disturbances. Although this attribution needs to be confirmed, this finding speaks against a global sleep-disruptive stress response and is more consistent with a vulnerability to transient, situationally related insomnia (15,16).

It is also not possible to determine if the s allele predisposes individuals to have acute difficulty with sleep in response to a stressor or if they have a predisposition to developing an autonomous chronic insomnia. The former is often referred to as transient insomnia, short-term or situational insomnia, which is characterized by a brief period of sleep disturbance in response to a disturbance in an otherwise normal sleeper, which resolves shortly after the stressor resolves (15,16). In this model, the s allele would constitute a predisposing factor for the development of sleep difficulty and would presuppose that caregivers experience ongoing stressors to which they are uniquely vulnerable (31). The possibility that the s allele could relate to a tendency for a subset of individuals to have greater sleep disturbance across different types of acute stressors (15,16) suggests the importance of studying the sleep of s carriers in response to a range of other types of acute stressors.

In addition, it is important to consider the possible role of major depression. It has been shown that that the 5-HTTLPR s allele is associated with an increased risk for depression in individuals, who have experienced significant stress, and furthermore, it is known that that depression is associated with poor sleep. Thus, it is possible that the poorer sleep quality observed in our caregivers, as compared with controls, is due to the fact that they are more depressed. Finally, recent research (32) has revealed the existence of a common single base substitution (A→G) within the 5-HTTLPR L allele, with the rarer LG allele showing reduced transcriptional efficiency, comparable to that of the S allele, although the LA allele is about twice as transcriptionally efficient as the S or LG alleles. It is not presently known whether consideration of the Lg/La base substitution would alter the current findings.

The increasing prevalence of sleep difficulties and the evidence of their impact on health, ability to function, and quality of life suggest that it is critical to understand better the potential moderators of sleep difficulty (14,33). Given that roughly 40% of the population reports a current problem with their sleep, there is a great potential to improve public health and well-being (33). If replicated, the current findings may identify a relationship of the s allele with sleep problems in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, who play an increasingly important societal role. Caregivers homozygous for the s allele are shown in our results to be accounting for the poorer sleep quality that we and others find associated with the caregiving role.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01AG19605 from the National Institute on Aging, with co-funding by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Institute of Mental Health; grant M01RR30 from the Clinical Research Unit; and by the Duke Behavioral Medicine Research Center.

- 5HT

serotonin

- 5-HTTLPR

5HTT gene-linked polymorphic region

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- 5HIAA

CSF levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- SE

standard error

References

- 1.Landolt H, Meier V, Burgess HJ, Finelli LA, Cattelin F, Achermann P, Borbely AA. Serotonin-2 receptors and human sleep: effect of a selective antagonist on EEG power spectra. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:455–66. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick DA. Neurotransmitter actions in the thalamus and cerebral cortex and their role in neuromodulation of thalamocortical activity. Prog Neurobiology. 1992;39:337–88. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottesmann C. Brain inhibitory mechanisms involved in basic and higher integrated sleep processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;45:230–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jouvet M. Sleep and serotonin: an unfinished story. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):24S–7S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberndorfer S, Saletu-Zyhlarz G, Saletu B. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on objective and subjective sleep quality. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42:69–81. doi: 10.1159/000026676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg B, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–31. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collier DA, Stober GTL, Heils A, Catalano M, Di Bella D, Arranz MJ, Murray RM, Vallada HP, Bengel D, Muller CR, Roberts GW, Smeraldi E, Kirov G, Sham P, Lesch KP. A novel functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene: possible role in susceptibility to affective disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:453–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RB, Marchuk DA, Gadde KM, Barefoot JC, Grichnik K, Helms MJ, Kuhn CM, Lewis JG, Schanberg SM, Stafford-Smith M, Suarez EC, Clary GL, Svenson IK, Siegler IC. Serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and central nervous system serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:533–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann JJ, Huang YY, Underwood MD, Kassir SA, Oppenheim S, Kelly TM, Dwork AJ, Arango V. A serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and prefrontal cortical binding in major depression and suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:729–38. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shioe K, Ichimiya T, Suhara T, Takano A, Sudo Y, Yasuno F, Hirano M, Shinohara M, Kagami M, Okubo Y, Nankai M, Kanba S. No association between genotype of the promoter region of serotonin transporter gene and serotonin transporter binding in human brain measured by PET. Synapse. 2003;48:184–8. doi: 10.1002/syn.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith GS, Lotrich FE, Malhotra AK, Lee AT, Ma Y, Kramer E, Gregersen PK, Eidelberg D. Effects of serotonin transporter polymorphisms on serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:2226–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:473–81. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Dongen HPA, Baynard MD, Maislin G, Dinges DF. Systematic interindividual differences in neurobehavioral impairment from sleep loss: evidence of trait-like differential vulnerability. Sleep. 2004;27:423–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Dongen HPA, Viterllaro KM, Dinges DF. Individual differences in adult human sleep and wakefulness: leitmotif for a research agenda. Sleep. 2005;28:479–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake C, Richardson G, Roehrs T, Scofield H, Roth T. Vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance and hyperarousal. Sleep. 2004;27:285–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Situational insomnia: consistency, predictors, and outcomes. Sleep. 2003;26:1029–36. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.8.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, Vitaliano PP, Ballard EL, Gwyther LP, Williams RB. Associations among perceptions of social support, negative affect, and quality of sleep in caregivers and non-caregivers. Health Psychol. 2006;25:220–5. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Dura JR, Speicher CE, Trask J, Glaser R. Spousal caregivers of dementia victims: longitudinal changes in immunity and health. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:345–62. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Putzhammer A, Schoeler A, Rohrmeier T, Sand P, Hajak G, Eichhammer P. Evidence of a role for the 5-HTTLPR genotype in the modulation of motor response to antidepressant treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:303–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Argyropoulos SV, Wilson SJ. Sleep disturbances in depression and the effects of antidepressants. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17:237–45. doi: 10.1080/09540260500104458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatric Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:631–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eley TC, Sugden K, Corsico A, Gregory AM, Sham P, McGuffin P, Plomin R, Craig IW. Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:908–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barr CS, Newman TK, Schwandt M, Shannon C, Dvoskin RL, Lindell SG, Taubman J, Thompson B, Champoux M, Lesch KP, Goldman D, Suomi SJ, Higley JD. Sexual dichotomy of an interaction between early adversity and the serotonin transporter gene promoter variant in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12358–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viola AU, Brandenberger G, Toussaint M, Bouhours P, Macher JP, Luthringer R. Ritanserin, a serotonin-2 receptor antagonist, improves ultradian sleep rhythmicity in young poor sleepers. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:429–34. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharpley AL, Elliott JM, Attenburrow MJ, Cowen PJ. Slow wave sleep in humans: role of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:467–71. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.an Laar M, Volkerts E, Verbaten M. Subchronic effects of the GABA-agonist lorazepam and the 5-HT2A/2C antagonist ritanserin on driving performance, slow wave sleep and daytime sleepiness in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:189–97. doi: 10.1007/s002130000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjorvatn B, Ursin R. Changes in sleep and wakefulness following 5-HT1A ligands given systemically and locally in different brain regions. Rev Neurosci. 1998;9:265–73. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1998.9.4.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pezawas L, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz RE, Kolachana BS, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Hariri AR, Weinberger DR. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulated-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;6:828–34. doi: 10.1038/nn1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dauvilliers Y, Morin C, Cervena K, Carlander B, Touchon J, Besset A, Billiard M. Family studies in insomnia. J Psychosomat Res. 2005;58:271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Traubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, Murphy DL, Goldman D. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Gen. 2006;78:815–26. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characterisitcs of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation survey I. Sleep. 1999;22:S347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]