Abstract

Background

A cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients represents an opportunity to study missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis. Primary objective: To study the epidemiology of diagnostic delays and failures to offer/complete CRC screening. Secondary objective: To identify system- and patient-related factors that may contribute to diagnostic delays or failures to offer/complete CRC screening.

Methods

Setting: Rural Veterans Administration (VA) Healthcare system. Participants: CRC cases diagnosed within the VA between 1/1/2000 and 3/1/2007. Data sources: progress notes, orders, and pathology, laboratory, and imaging results obtained between 1/1/1995 and 12/31/2007. Completed CRC screening was defined as a fecal occult blood test or flexible sigmoidoscopy (both within five years), or colonoscopy (within 10 years); delayed diagnosis was defined as a gap of more than six months between an abnormal test result and evidence of clinician response. A summary abstract of the antecedent clinical care for each patient was created by a certified gastroenterologist (GI), who jointly reviewed and coded the abstracts with a general internist (TW).

Results

The study population consisted of 150 CRC cases that met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 69.04 (range 35-91); 99 (66%) were diagnosed due to symptoms; 61 cases (46%) had delays associated with system factors; of them, 57 (38% of the total) had delayed responses to abnormal findings. Fifteen of the cases (10%) had prompt symptom evaluations but received no CRC screening; no patient factors were identified as potentially contributing to the failure to screen/offer to screen. In total, 97 (65%) of the cases had missed opportunities for early diagnosis and 57 (38%) had patient factors that likely contributed to the diagnostic delay or apparent failure to screen/offer to screen.

Conclusion

Missed opportunities for earlier CRC diagnosis were frequent. Additional studies of clinical data management, focusing on following up abnormal findings, and offering/completing CRC screening, are needed.

Background

A growing body of evidence shows that mishandled test results represent a threat to patient safety. In medical records review studies focusing on specific clinical pathology laboratory values (e.g., thyroid stimulating hormone, potassium, hemoglobin a1c, and glucose), 2-18% of cases were found to have clinically significant abnormalities but no evidence of clinician awareness [1-3]. Likewise, studies focusing on specific image types (e.g., mammograms, bone densitometry, and findings of incidental aortic aneurysms) found that 25-40% of cases with clinically significant abnormalities did not have documentation of a clinician response [4-6]. Surveys of primary care providers found that, within the two weeks prior to interview, the majority had seen a patient who had experienced a treatment delay due to missed results [7-10].

A study by Roy [11], found that nearly 1% of hospitalized patients had a significantly abnormal result lost to follow up in the transition between hospital and outpatient care. Numerous studies of diagnostic error utilizing litigation databases have found system-related errors; the most frequent was mishandling of abnormal test results, which was often associated with delays in cancer diagnosis [12-14]. In a cohort study of prostate cancer patients, Nepple et al. [15] found that in more than 16% of the cases, abnormal prostate-specific antigen (PSA) results were identified more than six months prior to documented clinician awareness and the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Various cancers for which patients are commonly screened represent a potential venue in which to study the prevalence of missed results. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common cancer [16], and primary care clinicians and the public are aware of recommendations to screen average-risk individuals beginning at age 55. Colonoscopy (CS) is the method of CRC screening preferred by the American Cancer Society and American Gastroenterological Association, while the US Public Health Service Task Force on Preventive Services and the Veterans' Administration (VA) [17] also endorse flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) and the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) as acceptable modalities for CRC screening. The VA is an excellent venue for studying the prevalence of missed screening opportunities, as it is an integrated healthcare system characterized by a relatively stable patient population and a high rate of CRC screening. The VA's electronic medical record (EMR) system, which is called the Computerised Patient Record System (CPRS), gathers together each patients' clinical notes, along with their clinical, laboratory, imaging, and pathology data [18-20]; thus, the CPRS contains many of the features considered desirable for decreasing the risk of lost test results, and missed screening [21,22].

Our hypothesis was that despite the VA's excellent reputation for patient safety, high rate of documented CRC screening, and state-of-the-art EMR, we would find many patients with missed screening and/or abnormal findings that were lost to follow up, but that could have led to earlier diagnosis of CRC if pursued. The primary examined outcomes were a delay greater than six months between abnormal findings and their subsequent evaluation, and the completion of CRC screening prior to diagnosis. The secondary objectives included the identification of patient- and system-related factors that might be associated with diagnostic delay and/or the lack of CRC screening. We chose to combine missed screening and abnormal findings that were lost to follow up (i.e. missed), as both may lead to the same detrimental outcome.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The setting was a VA health care system located in the upper Midwest. This VA provides medical care for over 45,000 veterans annually; primary care is provided in diverse settings across the system, including internal medicine resident continuity care clinics, two hospital-based primary care teams composed of VA providers (physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners), and six smaller community-based outpatient satellite clinics (CBOC), ranging in size from one to nine provider clinics. During the study period, a minority of the primary care was provided in the resident clinics (5%), with the remainder provided in the CBOC (50%) or the hospital-based VA staff clinics (45%). Gastroenterology care was provided at the VA medical center by faculty members and gastroenterology fellows holding dual appointments with the VA and an affiliated medical school. Flexible sigmoidoscopy was provided by primary care clinicians, gastroenterology physicians and fellows, and nurse sigmoidoscopists trained in GI procedures. A minority of colonoscopy screening services were provided by contracted gastroenterologists located in the local communities.

The inclusion criteria were: initial diagnosis of CRC made in the studied VA healthcare system and the availability of clinical notes within CPRS. All CRC cases in the VA tumor registry diagnosed between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2006 were reviewed. Data were obtained from provider progress notes, nurse notes, appointments, laboratory orders, imaging reports, clinical pathology reports, and anatomic pathology reports.

Data Collection and Measurement

The collected patient characteristics included: age; the locale in which the patient generally received primary care; comorbid diagnoses; the stage, grade, and location of CRC; and the location of colonic adenomas. Advanced cancer stage was defined as Stage III or Stage IV. Distal location was defined as rectum, sigmoid, or recto-sigmoid. For each patient, a board-certified gastroenterologist reviewed the antecedent medical care records stretching back to the initial contact with the VA or 1995 (whichever came first), and distilled the information into a one-page summary (or clinical abstract). Each clinical abstract included information on CRC screening competed outside the VA, antecedent signs or symptoms, the time between positive findings and subsequent evaluation, any factors that could have contributed to a delay in evaluation, and the reasons for CRC diagnosis.

The included CRC screening modalities were FOBT, barium enema (BE), flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS), and colonoscopy (CS). Completed screening was defined as documented completion of CRC screening outside the VA in the five years (10 years for CS) prior to CRC diagnosis, or the availability of these results in CPRS (i.e. completion of tests within the VA) within this same period. Issues and circumstances that were believed to potentially contribute to diagnostic delay were classified as either patient- or system-related factors (Table 1). Delay was defined as a gap of more than six months between the detection of abnormal findings and completion of CRC evaluation. The abovementioned patient- and system-related factors were also collected from patients for whom no prior CRC screening was documented. Completed evaluation was defined as a clinical explanation of the abnormal findings. The clinical abstracts were reviewed by TW and IP and coded through consensus.

Table 1.

Patient- and system-related factors with diagnostic delay

| Patient Factors |

| Frequent appointment no-shows |

| Frequent appointment cancellations |

| Declined evaluation |

| Medical comorbidity |

| Poor-quality information from patient history |

| Reference to patient noncompliance |

| Significant psychiatric diagnosis |

| Homelessness |

| System factors |

| Scheduling delay for colonoscopy |

| Incorrect Interpretation of results |

| Judgment error by clinician |

| Communication failure of clinician |

| Inexperience of clinician |

| Abnormal findings likely lost to follow up |

| Outside records not obtained |

| Weight (wt) loss not evaluated |

| Anemia not evaluated |

| FOBT request |

| Positive FOBT |

| Abnormal flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy or polyp biopsy results |

| Abnormal barium enema or CAT scan results |

| Lesion missed by colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy |

| Lesion missed by barium enema |

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Iowa and the Iowa City VAMC.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 156 patients newly diagnosed with CRC during the study period, 150 met the study inclusion criteria. The mean age at diagnosis was 69.04 years. Sixty-seven (44%) cases had late stage CRC, and 71 (47%) had a distal CRC location. Fifty-one cases were found through screening. FOBT was used as the initial screening modality in 14 cases; other screening modalities included FS (26 cases), and CS (9 cases). In two patients, CRC was detected by surveillance colonoscopy performed because of a personal history of adenomatous colonic polyps. Eighteen cases were diagnosed as part of the patient's initial contact with the VA, two because of a positive CRC screening completed as part of the initial health-maintenance screening, and 16 because of symptoms present at the time of initial contact. Ninety-nine cases were found due to symptoms; these included 43 cases (29%) with anemia, and 22 (15%) with either rectal bleeding or melena. For more detail, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons for diagnosis of CRC

| All CRC cases (N = 150) | Veterans diagnosed as part of initial presentation to VA (N = 18) | |

| Initial reason for diagnosis | ||

| Positive fecal occult blood test | 14 | 0 |

| Positive flexible sigmoidoscopy | 26 | 2 |

| Positive colonoscopy | 9 | 0 |

| Hx polyp | 2 | 0 |

| Total found through screening | 51 | 2 |

| Rectal bleeding or melena | 22 | 5 |

| Anemia | 43 | 4 |

| Pain | 13 | 0 |

| Wt loss | 10 | 4 |

| Abnormal CT scan | 4 | 0 |

| Metastatic disease | 8 | 3 |

| Total found through investigation of symptoms | 99 | 16 |

CRC Screening

Ninety-eight patients (65%) had CRC screening documented prior to diagnosis; 48 (32%) had received FOBT, 31 (20.3%) had received FS, and 19 (12.4%) had received CS. Two cases were under 50 years old, and three cases were over 80 years old. Forty cases that were age-appropriate for screening lacked documentation of CRC screening being completed or offered. The medical records for four of the un-screened cases had documentation of an offer to screen; three also had documentation that the patient had declined screening. From among the cases, 19 and 24 had patient- and system-related factors, respectively, that were believed to potentially contribute to either the absence of screening or diagnostic delay. Twenty-one patients were age-appropriate for screening and had received prior ongoing, longitudinal care from the VA; of them, 16 had no documentation of CRC screening being offered or completed. Of the 71 cases with distally located CRC, 44 had no documentation of offered/completed CRC screening. Twenty-six of the cases without diagnostic delay lacked documentation of CRC screening prior to diagnosis. For more detail, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Documentation of completed CRC screening in the medical record

| Total cases with no documentation of CRC screening completed prior to diagnosis | 45 |

| No Screen: Age < 50 y/o | 2 |

| No Screen: Age > 80 y/o | 3 |

| No Screen: Age ≥50 and ≤80 y/o | 40 |

| Documented offer to screen + patient declination of screening | 3 |

| Documented offer to screen but lost to follow up | 1 |

| Patient factors identified (N = 19 cases) | 19 |

| Frequent no-shows/cancellations | 7 |

| Declined therapy/evaluation | 11 |

| Comorbidity | 7 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 6 |

| Homelessness | 3 |

| System factors identified (N = 24 cases) | 24 |

| Scheduling delays | 3 |

| Abnormal findings lost to follow up | 21 |

| Wt loss | 3 |

| Anemia | 13 |

| FBOT request | 1 |

| Judgment error by clinician | 3 |

| No screening despite appropriate age, no patient factors identified, and ongoing antecedent care with the VA | 21 |

Cases with Delays in the Evaluation of Abnormal Findings

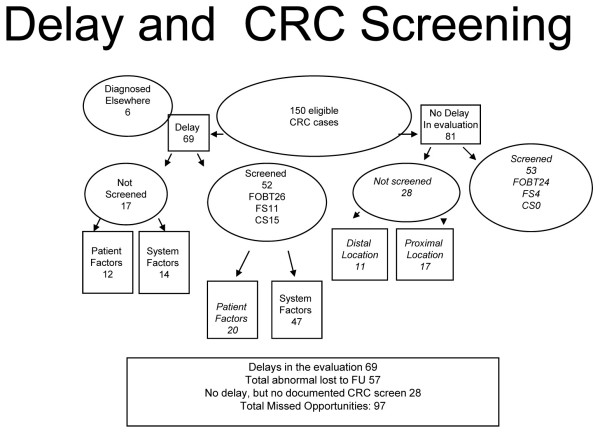

In 69 cases, more than six months elapsed between the abnormal test results and diagnosis of CRC. A total of 212 individual system factors were identified in 61 cases (mean 3.8 per case, range 0-8). A total of 56 individual patient factors were identified in 32 cases (mean 3.1 per case, range 0-10). For more detail, see Figure 1. Both patient- and system-related factors were identified in 25 cases, and two or more factors were identified in 63 cases. For more detail, see Tables 4 and 5.

Figure 1.

Flow chart summarizing the presence of prior CRC screening and apparent diagnostic delay.

Table 4.

Delays and frequency of possible contributory factors

| System factors | Delay obtaining colonoscopy due to scheduling issues | Abnormal findings lost to FU per case | Patient factors | All reported factors | |

| Total number of factors reported | 212 | 6 | 101 | 56 | 268 |

| Mean number of factors reported per case | 3.1 | 0.09 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 3.9 |

Table 5.

Factors contributing to diagnostic delay

|

Factors that may have contributed to the development of delay (N = 69 cases) |

Number of factors identified |

| Patient factors (N = 32 cases) | 56 |

| Frequent appointment no-shows | 9 |

| Patient declined evaluation | 16 |

| Comorbidity | 18 |

| Frequent appointment cancellations | 4 |

| Poor information from patient history | 0 |

| Noncompliance | 0 |

| Major psychiatric diagnosis | 8 |

| Homelessness | 1 |

| System factors (N = 61 cases) | 212 |

| Delay in CS scheduling due to backlog in VA | 4 |

| CS or FS missed the lesion(s) | 10 |

| Barium enema missed the lesion(s) | 1 |

| Incorrect interpretation of findings | 1 |

| Error in clinical judgment | 1 |

| Communication breakdown | 1 |

| Inexperience of clinician | 0 |

| Abnormal findings likely lost to follow up (N = 57 cases) | 101 |

| Review/obtain outside records | 8 |

| Wt loss | 7 |

| Anemia | 41 |

| Positive family history | 2 |

| FOBT request | 4 |

| Positive FOBT | 22 |

| Abnormal colon polyp biopsy | 3 |

| Abnormal imaging | 2 |

| Hematochezia | 3 |

| Abnormal findings lost to follow up with no patient factors identified | 33 |

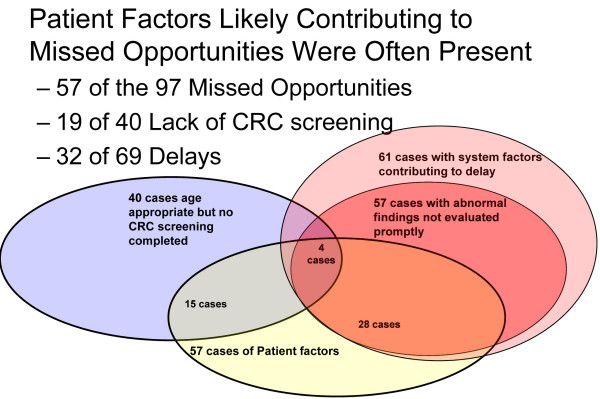

In 11 cases, a diagnostic or imaging procedure appeared to have missed an existing lesion (barium enema in one case, CS or FS in 10 cases). A total of 101 different abnormal findings in 57 cases failed to receive a completed evaluation within six months. The two most frequent abnormal findings that failed to receive a completed evaluation within six months were anemia (41 cases) and positive FOBT (22 cases). Thirty-two of the cases with delayed evaluation of abnormal findings were found to have patient factors that may have contributed to the development of delay. These included patient declination of evaluation (16 cases), frequent patient-initiated appointment cancellations (4 cases) and no-shows (9 cases), comorbid medical conditions (16 cases), comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (8 cases), and homelessness (1 case). Thirty-three cases with delays had no identified patient factors. For more detail, see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patient factors that appear to contribute to diagnostic delay or the absence of CRC screening.

Discussion

In nearly two thirds of the CRC cases examined in the present study, an opportunity for earlier diagnosis had been missed. Half of the distally located cancer cases had no prior CRC screen, and a third of the studied CRC cases lacked documentation of CRC screening having been offered or completed prior to diagnosis. Delays associated with system errors were noted in over a third of all CRC cases, with delayed response to anemia and positive FOBT comprising the most common errors. In addition, patient factors were identified in half of the cases with missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis. These data, though troubling, are consistent with the growing body of literature on diagnostic error and missed results. The present study found that while patient factors often contributed to delays, the majority of delayed diagnoses suffered from system factors, particularly lost follow up of abnormal findings. This relatively frequent loss of abnormal findings to follow up is consistent with several lines of evidence in the literature which have shown that delays are most often the result of an accumulation of multiple errors [12-14];

System factors were identified in two-thirds of the cases with delays; the vast majority involved failures to promptly evaluate abnormal findings. Although patient factors were often present, only eight cases involved underlying medical or psychiatric co-morbidities. Most delays had multiple system factors, including failure to screen. Although all of the relevant system factors should be addressed, the following focuses on issues related to the management and presentation of clinical data.

Because screening is recommended for colorectal, breast, cervical, and prostate cancer, a large volume of cancer screening tests may be requested and completed annually within the practice of a given primary care practitioner. Nationally, these four cancers together accounted for an estimated 532,000 new diagnoses and 124,000 deaths in 2007 [16]. Although public acceptance of cancer screening is relatively high, the rate of CRC screening remains below that for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer [24-27]. Patients often report they have not been counseled to seek CRC screening [28-30], even though primary care practitioners have begun to face malpractice litigation for diagnostic delay when cancer is diagnosed in the absence of a prior screen [13,31].

Hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of cancer screening diagnostics are requested and completed each year. With the typical primary care provider ordering over a thousand tests each week, providers can easily be overwhelmed by the volume of data that must be reviewed [22], increasing the risk of individual results being missed (i.e. lost to follow up). Although EMRs can efficiently deliver results to providers, this does not guarantee that the provider will interpret the findings correctly and respond appropriately [5,22]. The psychology literature demonstrates that as work increases and alarm sensitivity declines, 90% of individuals will produce progressively lower-quality work and their responsiveness to alarms will decline [32,33]. Furthermore, numerous studies have indicated that providers often ignore drug alert warnings [34-39] and even abnormal test results [39] within their EMR.

It is therefore necessary to improve the management and presentation of clinical data to providers. Lessons can be learned from the fields of industrial engineering and aviation [39,40], which have sought to redesign processes, data presentation, and decision making to ensure that the data volume is consistent with human limitations [41]. It could be helpful to develop computer algorithms capable of filtering data for abnormal results and recognizing when a positive finding has already been evaluated and is stable (and therefore is not a concern), with the goal of presenting clinicians with only information that requires a clinical response [10,41].

One solution that has been suggested to deal with data management issues is the direct notification of patients by the laboratory service upon completion of CRC screening [42]. While a slim majority of patients expressed a desire for direct notification, many physicians are uncomfortable with this solution as it can lead to increased patient anxiety and telephone calls, and additional non-compensated work for the clinicians [5]. However, when patients are not given their test results, they tend to be less motivated, experience lower levels of therapeutic adherence, and may have poorer outcomes [4,5,43,44].

Limitations

This study has two main limitations. First, VA patients can also receive healthcare services in the community. It is therefore possible that evaluations of abnormal findings and CRC screenings were completed in the community without being included in the VA EMR. However, we reviewed all primary care and GI progress, nurse, and procedure notes, which often explicitly stated whether screening had (or had not) occurred in the community. Furthermore, the medico-legal system places higher value on care that is documented in the medical record [43], and the present findings are consistent with those from prior studies documenting that 10% of CRC had been missed by prior imaging studies [45] and more than 10% of positive FOBTs receive inadequate follow up [46]. The second limitation is that this study was completed solely in the VA, and will thus require replication in other healthcare systems. However, the present results are consistent with those from a cohort of men diagnosed with prostate cancer, in which one out of five cases showed delays of more than six months between an abnormal PSA test result and documented clinician awareness [23]. Furthermore, multiple studies have shown that abnormal test results lost to follow up (i.e. missed results) occur in diverse settings (e.g., academic, private, VA, hospital, and ambulatory settings), involve a variety of staff types (e.g., trainees, staff physicians, and mid-level providers), and across multiple types of diagnostic studies [1-4,11,47]. As such, the present results add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that problems with consistent management of patient test result data contribute to diagnostic error and unnecessary diagnostic delays more often than is generally appreciated.

Conclusion

In a cohort of patients diagnosed with CRC, opportunities for earlier diagnosis were frequently missed. Contributory patient factors were identified in only half of the cases with delayed or absent CRC screening. Although clinicians were using an advanced EMR, this was insufficient to ensure CRC screening or prevent delays in the evaluation of abnormal findings. Additional studies are warranted to examine clinician management of abnormal laboratory test results and failure to document the offer and/or completion of CRC screening.

Competing interests

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Authors' contributions

TW and IP participated in the study concept, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. IP completed the statistical analyses. TW provided administrative and clerical support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Financial Disclosures: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding/Support: This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities in the Center for Research in the Implementation of Innovative Strategies in Practice (CRIISP) at the Iowa City VA Medical Center. This study received no grant support. These data were presented at the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois on September 28, 2007

Role of the Sponsor: Not applicable

These data have been presented at the Annual Society of General Internal Medicine Conference, Pittsburg, PA, April 11, 2008.

Contributor Information

Terry L Wahls, Email: Terry.Wahls@va.gov.

Ika Peleg, Email: Ika-Peleg@ouhsc.edu.

References

- Edelman D. Outpatient diagnostic errors: unrecognized hyperglycemia. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff GD, Aggarwal HC, Kumar S, McNutt RA. Prescribing potassium despite hyperkalemia: medication errors uncovered by linking laboratory and pharmacy information systems. Am J Med. 2000;109:494–497. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff GD, Kim S, Krosnjar N, Wisniewski MF, Bult J, Fogelfeld L, McNutt RA. Missed hypothyroidism diagnosis uncovered by linking laboratory and pharmacy data. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:574–577. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon EG, Haas JS, Louise PA, Gandhi TK, Burdick E, Bates DW, Brennan TA. Communication factors in the follow-up of abnormal mammograms. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Rosenthal GE, Ohsfeldt R, Wallace RB, Schlechte J, Schiff GD. Failure to recognize and act on abnormal test results: the case of screening bone densitometry. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:90–97. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JR, Wahls T, Carlos RC, Pipinos II, Rosenthal GE, Cram P. Failure to recognize newly identified aortic dilations in a health care system with an advanced electronic medical record. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:21–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson AS, Bates DW. "I wish I had seen this test result earlier!": Dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2223–2228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls T, Haugen T, Cowell K, Becker W. Improving diagnostic results reporting in the Veterans Administration. Federal Practioner. 2006;23:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wahls T, Haugen T, Cram P. The continuing problem of missed test results in an integrated health system with an advanced electronic medical record. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:485–492. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls TL, Cram PM. The frequency of missed test results and associated treatment delays in a highly computerized health system. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, Gandhi TK. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121–128. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-2-200507190-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Petersen LA, Thomas EJ. Understanding diagnostic errors in medicine: a lesson from aviation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:159–164. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohan TV, Colestro J, Grippi J, Converse J, Hughes M. Analysis of diagnostic error in paid malpractice claims with substandard care in a large healthcare system. South Med J. 2005;98:1083–1087. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000170729.51651.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepple KG, Joudi FN, Hillis SL, Wahls TL. Prevalence of delayed clinician response to elevated prostate-specific antigen values. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:439–445. doi: 10.4065/83.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer screening in the United States, 2007: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:90–104. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Perlin JB, Steinman MA, Peabody JW, Ayanian JZ. Quality of ambulatory care for women and men in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:762–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:828–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Healthc Pap. 2005;5:10–24. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..17381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murff HJ, Gandhi TK, Karson AK, Mort EA, Poon EG, Wang SJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW. Primary care physician attitudes concerning follow-up of abnormal test results and ambulatory decision support systems. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71:137–149. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon EG, Wang SJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, Kuperman GJ. Design and implementation of a comprehensive outpatient Results Manager. J Biomed Inform. 2003;36:80–91. doi: 10.1016/S1532-0464(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepple , Joudi F, Hillis , Wahls T. The Prevalence of Delayed Clinician Response to Elevated Prostate-Specific Antigen Values. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008 doi: 10.4065/83.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzlsouer KJ, Ford DE, Hayward RS, Midzenski M, Perry H. Perceived risk of cancer and practice of cancer prevention behaviors among employees in an oncology center. Prev Med. 1994;23:302–308. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson S, Correa-de-Araujo R. Preventive health examinations: a comparison along the rural-urban continuum. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos RC, Underwood W, III, Fendrick AM, Bernstein SJ. Behavioral associations between prostate and colon cancer screening. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos RC, Fendrick AM, Patterson SK, Bernstein SJ. Associations in breast and colon cancer screening behavior in women. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WF, McGloin J, Zittleman L, West DR, Westfall JM. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J Rural Health. 2007;23:238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med. 2005;41:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan AH, Skinner CS, Rawl SM, Moser BK, Champion VL, Scott LL, Strigo TS, Bastian L. Patients' interest in discussing cancer risk and risk management with primary care physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L. Liability for failure to order screening examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1401–1405. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss JP, Gilson RD, Deaton JE. Human probability matching behaviour in response to alarms of varying reliability. Ergonomics. 1995;38:2300–2312. doi: 10.1080/00140139508925269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss JP, Dunn MC. Behavioural implications of alarm mistrust as a function of task workload. Ergonomics. 2000;43:1283–1300. doi: 10.1080/001401300421743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall MA, Sittig DF. Clinician's assessments of outpatient electronic medical record alert and reminder usability and usefulness requirements. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:400–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall MA, Sittig DF. Subjective assessment of usefulness and appropriate presentation mode of alerts and reminders in the outpatient setting. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:334–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim MI, Mintz RJ, Boyer AG, Frayer WW. Design of a clinical alert system to facilitate development, testing, maintenance, and user-specific notification. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000:630–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TH, Nichol WP, Hoey P, Savarino J. Characteristics and override rates of order checks in a practitioner order entry system. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:602–606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NR, Seger AC, Seger DL, Fiskio JM, Kuperman GJ, Blumenfeld B, Recklet EG, Bates DW, Gandhi TK. Improving acceptance of computerized prescribing alerts in ambulatory care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:5–11. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Arora HS, Vij MS, Rao R, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Communication outcomes of critical imaging results in a computerized notification system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:459–466. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf-Miron R, Lewenhoff I, Benyamini Z, Aviram A. From aviation to medicine: applying concepts of aviation safety to risk management in ambulatory care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:35–39. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2526–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung S, Forman-Hoffman V, Wilson MC, Cram P. Direct reporting of laboratory test results to patients by mail to enhance patient safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1075–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Stromborg M, Bailey LJ. Cancer screening and early detection: managing malpractice risk. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:206–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006004206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy BD, Yood MU, Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Rebner M, Johnson CC. Inadequate follow-up of abnormal mammograms. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen M, Raiha I, Rajala T, Sourander L. Delay in diagnosis of colorectal cancer in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1993;22:260–264. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.4.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Kammer D, Bond JH, Ho SB. Evaluating follow-up of positive fecal occult blood test results: lessons learned. J Healthc Qual. 2007;29:16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JR, Wahls TL, Carlos P, Cram P. Lost in the Clutter Missed Aortic Aneurysms in Spite of an Advanced Electronic Medical Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1–276. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0176-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]