Abstract

Background

Mesophotic corals (light-dependent corals in the deepest half of the photic zone at depths of 30 - 150 m) provide a unique opportunity to study the limits of the interactions between corals and endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium. We sampled Leptoseris spp. in Hawaii via manned submersibles across a depth range of 67 - 100 m. Both the host and Symbiodinium communities were genotyped, using a non-coding region of the mitochondrial ND5 intron (NAD5) and the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2), respectively.

Results

Coral colonies harbored endosymbiotic communities dominated by previously identified shallow water Symbiodinium ITS2 types (C1_ AF333515, C1c_ AY239364, C27_ AY239379, and C1b_ AY239363) and exhibited genetic variability at mitochondrial NAD5.

Conclusion

This is one of the first studies to examine genetic diversity in corals and their endosymbiotic dinoflagellates sampled at the limits of the depth and light gradients for hermatypic corals. The results reveal that these corals associate with generalist endosymbiont types commonly found in shallow water corals and implies that the composition of the Symbiodinium community (based on ITS2) alone is not responsible for the dominance and broad depth distribution of Leptoseris spp. The level of genetic diversity detected in the coral NAD5 suggests that there is undescribed taxonomic diversity in the genus Leptoseris from Hawaii.

Background

Images of colonial corals illuminated by sunlight are dominant in the literature, in part because the majority of hermatypic coral species are found in the top 30 m of the photic zone [1]. This distribution reflects their reliance on sunlight to support their photosynthetic symbiotic dinoflagellates, partners that reside within the gastrodermal cells of all hermatypic corals. These dinoflagellates (genus Symbiodinium) enhance calcification [2] and translocate fixed carbon to the host where it is respired, and provides the majority of the metabolic needs of the host [3]. This intimate symbiosis between corals and dinoflagellates underpins the ecological success of corals in the nutrient poor environments of tropical and subtropical marine ecosystems [2].

Despite the general public perception that zooxanthellate scleractinian corals are confined to shallow well-lit waters, they exist throughout the entire euphotic zone, from full sunlight to virtual darkness [4]. Zooxanthellate corals have been recorded as deep as 165 m in the Pacific (Leptoseris hawaiiensis, Johnson Atoll [5]). In Hawaii, the hermatypic coral genus Leptoseris (Family Agariciidae) is present at shallower depths, but deep water surveys found Leptoseris dominates the mesophotic zone [6], where it is apparently able to photosynthesize at light levels as low as 1% of the surface light intensity [6,7]. Previous deep water surveys reported three dominant Leptoseris species from Hawaii, L. hawaiiensis, L. yabei (previously unknown to Hawaii), and an undescribed congeneric species, and highlighted the need for more research on these mesophotic corals, particularly their systematics [6,7].

What underlies this extraordinary physiological range and depth distribution of Leptoseris corals is unknown, but it is likely that attributes and adaptations in both the endosymbiotic community and coral host are involved [8]. Examining this symbiotic association at the limits of the photic zone may help us understand the interactions by which reef corals cope with and adjust to extremes in the environment. To begin to unravel the traits that allow Leptoseris spp. to exploit deep habitats, this study uses molecular genetic techniques to examine the interaction between endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium and mesophotic corals in the genus Leptoseris. Because of the difficulties inherent in collecting samples below traditional SCUBA depths, this study represents one of the first to examine the genetics of coral-algal associations at depths below 67 m in Hawaii.

Under different light regimes, coral hosts and their endosymbiotic dinoflagellates maintain high rates of photosynthetic carbon translocation by photoacclimation. This is achieved in some corals and their endosymbionts by changes in the cellular concentrations of photosynthetic pigment [9]. However, some symbiotic organisms (e.g. Anemonia viridis [10]) show minimal changes in the photosynthetic pigments of their endosymbionts with changes in light. These differences in physiological flexibility may reflect taxonomic differences in the composition or identity of the endosymbiotic dinoflagellate communities in the different coral species [11]. Although it was initially believed that all corals hosted a single species of dinoflagellate (Symbiodinium microadriaticum. Freudenthal, 1962), molecular genetics have demonstrated that the genus Symbiodinium is extremely diverse and a single coral can host multiple, co-occurring endosymbiotic strains [12,13]. Phylogenetic analyses of the genus Symbiodinium, based primarily on nuclear ribosomal genes, have led to the current recognition of eight major lineages or clades (A through H) [12,14] that are each partitioned further into sub-cladal types, most frequently using the quickly evolving internal transcribed spacer regions of the ribosomal DNA operon [15].

To date, several patterns have been detected in the distribution of Symbiodinium taxa with depth (all studies ≤ 40 m), suggesting that light tolerance in Symbiodinium may drive the distributions of host coral colonies [16-18]. Irradiance could therefore be an important determinant in the distribution of Symbiodinium, with different Symbiodinium genotypes dominating the light environments for which their photosynthetic characteristics are best adapted [11,19].

Characterizing the Symbiodinium communities found in mesophotic corals such as Leptoseris spp. is an obvious first step in exploring how these corals are able to survive and thrive at such depths. Given the unique environmental characteristics and extremely low light levels in the mesophotic zone, we hypothesized that Leptoseris spp. from the deep mesophotic (67-100 m) would host highly specialized and unique Symbiodinium types found only at these depths.

Results

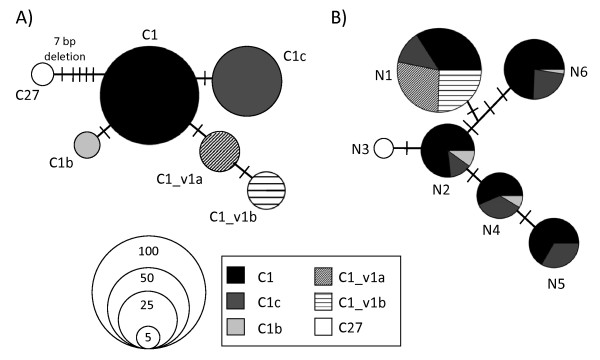

Six Symbiodinium genotypes were recovered and analyzed from 15 deep (67-100 m) Leptoseris spp. samples. All were phylogenetically identified as belonging to clade C. Four of the sequences have been previously published (C1_ AF333515, C1c_ AY239364, C27_ AY239379, and C1b_ AY239363) and two were novel and differed from known sequences by one or two base pairs (bp). These sequences were named C1_v1a and C1_v1b, because they differed from type C1 by one and two bp, respectively. C27 includes a seven bp indel, one bp indel, and three polymorphic sites (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Genotype networks showing relationships between types for A) Symbiodinium ITS2 types and B) Leptoseris mitochondrial intron NAD5. For both A) and B) number of clones indicated by the size of the circle to scale, and hatch marks indicate base pair changes/indels between genotypes. For B) pie contents indicate the frequency of Symbiodinium ITS2 types recovered from the six Leptoseris NAD5 haplotypes.

The 15 Leptoseris samples grouped as six mitochondrial NAD5 haplotypes, identified by seven polymorphic sites and named N1-N6 (Figure 1B).

The association between Symbiodinium type and host mitochondrial haplotype was not random (Fisher's exact test, 10,000 random permutations, p < 0.01). Leptoseris corals with haplotypes N2, N4, N5, and N6 (n = 10 colonies in total) hosted endosymbiont communities dominated by Symbiodinium types C1 and C1c (Table 1). Leptoseris corals with haplotype N1 (n = 4 colonies) had more diverse Symbiodinium communities, harboring C1, C1c, C1_v1a and C1_v1b. N1 was the only coral haplotype to associate with Symbiodinium types C1_v1a and C1_v1b, which always co-occurred in a sample. Leptoseris haplotype N3 (n = 1) was the only sampled coral that hosted Symbiodinium type C27 (Table 1). It is important to note here that Symbiodinium type C1 always co-occurred with either one or a combination of the types C1c, C1b, C1_v1a and C1_v1b. Because intragenomic variation at the ITS-2 locus is high in Symbiodinium [20], one explanation would be that these co-occurring types represent intragenomic variants within the same symbiont genome rather than distinct genomes.

Table 1.

Number of clone sequences of each ITS2 type, the total number of clone sequences included (In.) in the analysis, and number of clone sequences excluded (Ex.) for each Leptoseris spp. (n = 15) sampled showing host location, depth, and haplotype.

| ITS2 type | No. of clones | ||||||||||

| Sample Name | Location | Depth (m) | MtDNA | C1 | C1_v1a | C1b | C1c | C27 | C1_v1b | In. | Ex. |

| N1_67m_1 | 20°47.840'N 156°43.048'W | 67 | N1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 8 | |||

| N1_70m_1 | 20°57.015'N 156°45.001'W | 70 | N1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 9 | |||

| N1_82m_1 | 20°47.675'N 156°43.047'W | 82 | N1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 13 | |||

| N1_98m_1 | 20°47.977'N 156°43.088'W | 98 | N1 | 9 | 6 | 15 | 4 | ||||

| N2_68m_1 | 20°57.015'N 156°45.001'W | 68 | N2 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| N2_68m_2 | 20°57.015'N 156°45.001'W | 68 | N2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |||

| N2_76m_1 | 20°56.504'N 156°45.418'W | 76 | N2 | 15 | 2 | 17 | 6 | ||||

| N3_74m_1 | 20°56.458'N 156°45.521'W | 74 | N3 | 4 | 4 | 9 | |||||

| N4_74m_1 | 20°56.458'N 156°45.521'W | 74 | N4 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 4 | |||

| N4_74m_2 | 20°56.458'N 156°45.521'W | 74 | N4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 1 | |||

| N5_74m_1 | 20°56.458'N 156°45.521'W | 74 | N5 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 4 | ||||

| N5_74m_2 | 20°56.458'N 156°45.521'W | 74 | N5 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 2 | ||||

| N6_79m_1 | 20°48.821'N 156°42.640'W | 79 | N6 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 2 | ||||

| N6_82m_1 | 20°47.675'N 156°43.047'W | 82 | N6 | 14 | 6 | 20 | 5 | ||||

| N6_100m_1 | 20°47.624'N 156°43.096'W | 100 | N6 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 6 | |||

Discussion

Leptoseris corals are some of the deepest-dwelling zooxanthellate corals in the world [7] and the biological attributes that underpin the ability of this genus to thrive across such a large depth range (as deep at 165 m [5]) are central to our understanding of limits of the coral-endosymbiont interaction. Intracellular photosynthetic dinoflagellate symbionts of the genus Symbiodinium are pivotal to the success of corals as a group and are known to be taxonomically and physiologically diverse [12]. We thus hypothesized that the Symbiodinium communities hosted by Leptoseris spp. in the mesophotic zone might be highly specialized to this environment and that this would be apparent as a pattern in the distribution of Symbiodinium types hosted by Leptoseris spp. over a depth gradient. Surprisingly, our data do not support this hypothesis; Leptoseris spp. sampled at 67 m and deeper, host Symbiodinium types commonly found in shallow-water corals across the Pacific [21]. Although endosymbiont diversity will vary by host species, this finding contradicts studies examining endosymbiont diversity in corals sampled across shallower depth gradients (≤ 40 m) that observed partitioning of Symbiodinium communities at the level of clade [16] and ITS2 types [17,22] by depth, and therefore, evidence for depth-based ecological function in symbionts. We found Symbiodinium ITS2 types C1 and C1c in mesophotic zooxanthellate corals. ITS2 type C1 has also been found in two Leptoseris incrustans colonies sampled in Hawaii between 10-20 m depth [21]. The generalist C1 Symbiodinium types are widely distributed both geographically and environmentally [21].

Solar radiation is a major determinant of photosynthesis, and therefore influences the amount of carbon translocated to the host, and the phototrophic contribution to the animal [23]. When light declines with depth, without photoacclimation, carbon fixation rates and the amount of translocated carbon declines [23]. Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea exhibit large changes in photosynthetic pigment concentrations with changes in depth [24]. Our results from Leptoseris spp. in Hawaii suggest that this may be a capacity of generalist Symbiodinium types such as C1 and C1c. However, confirming whether these abundant, generalist types have the ability to photoacclimate across the depth range under consideration here will require pigment studies and endosymbiont density counts and will be an important component of future research on the deep water corals in Hawaii.

Despite the focus on Symbiodinium and its ability to photoacclimate, the coral host can also influence photoacclimation. Research on Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea has shown possible photoadaptations in host light-harvesting systems that may enhance photosynthetic performance [25]. These include fluorescent pigments that may convert light at depth to wavelengths useable for photosynthesis [4], plate-like growth forms, and morphological adaptations like conical knobs that may serve as coral "light traps" [24]. Leptoseris in Hawaii also possess these three adaptations, but their influence on photosynthetic performance in Leptoseris spp. in Hawaii has yet to be directly demonstrated.

Furthermore, Leptoseris could differ from shallow corals in its reliance on phototrophic carbon because this coral could obtain more nutrients from feeding [26], or have reduced needs for nutrients with slower growth rates and lower metabolism [27]. For example, L. fragilis has trophic adaptations that may be responsible for minimizing their dependence on photosynthetically fixed carbon [28]. L. fragilis has a perforated gastrovascular cavity, resulting in a flow-through system where microscopic particulate organic material such as detritus, bacteria, and plankton can accumulate [28]. As light decreases with depth, greater reliance on feeding heterotrophically (rather than on phototrophy) may enable these corals to survive. However, to date, no studies have examined the relative contribution of photosynthetically fixed carbon to the daily energy budget of corals at these depths in Hawaii; such studies are critical to a more comprehensive understanding of Leptoseris's spp. broad depth distribution.

Given the known slow rate of evolution in coral mitochondrial DNA [29,30], the six distinct coral haplotypes we found likely represent multiple species and highlight unrecognized diversity in this coral genus. In a previous study using the NAD5 marker, Concepcion et al. (2006)[29] found no variation between species within the genus Acropora and Pocillopora, but for the genus Porites, P. asteroides and P. compressa differed by two indels, and P. porites and P. compressa by four single bp changes.

Interestingly, we found different Symbiodinium communities associated with different mitochondrial NAD5 haplotypes. Four of the coral mitochondrial types (N2, N4, N5, and N6) were dominated by C1 and C1c endosymbionts, however, N1 (n = 4 colonies) and N3 (n = 1 colony) showed different patterns of symbiont association (with C1, C1_v1a, and C1_v1b and with C27, respectively).

Conclusion

This study was a natural first step to exploring the biological traits that allow Leptoseris spp. to persist and dominate at mesophotic depths (i.e. 67 to 100 m depth). We found common shallow-water Symbiodinium types at depths not previously recorded for these endosymbionts. We also found genetic variability at mitochondrial NAD5, which suggests undescribed taxonomic diversity in Leptoseris. Mesophotic coral communities are found beyond the limits of traditional SCUBA diving and as a result, their ecology is poorly understood [6,7]. An understanding of the mechanism(s) by which reef corals adjust to extremes in the environment and the limits inherent to these mechanisms provides insights into the future responses of deep and shallow reef communities to environmental change. Our study indicates that a specialist symbiont is not a prerequisite for existence at environmental extremes.

Methods

Mesophotic corals (67-100 m depth) (n = 15) were collected using the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory's (HURL) manned submersibles, Pisces IV and V, during two cruises (October 2006 and December 2007) to the Au'au Channel (see Table 1 for sampling locations) between the islands of Maui and Lanai aboard R/V Kaimikai-o-Kanaloa. Leptoseris spp. fragments were broken off using the submersible's mechanical arm, brought to the surface and preserved in 95% Ethanol or DMSO buffer, or frozen at -80°C. Species level identifications of Leptoseris samples were problematic due to: (1) the small sizes of some of the collected specimens (due to breakage from the mechanical arm) making identification impossible, and (2) the finding of morphotypes that had previously not been reported from Hawaii [7,31]; therefore we refer to all the samples as Leptoseris spp. Sample size was limited due to the logistical challenges of obtaining deep-water specimens.

Genomic DNAs containing both the host and endosymbiotic dinoflagellates were extracted using a Guanidinium extraction protocol [32]. The Symbiodinium ITS2 rDNA marker was amplified using the primers itsD (forward; 5'-GTGAATTGCAGAACTCCGTG-3') and ITS2Rev2 (reverse; 5'-CCTCCGCTTACTTATATGCTT-3') [32,33] and Sahara DNA polymerase (Bioline, Randolph, MA, USA), a heat-activated high-fidelity complex of enzymes and immolase. PCRs totaled 25 μL and consisted of 2.5 μL of 10× PCR Buffer (Bioline), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 mM), 0.5 μL (2.5 mM of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 0.1 μL of DNA polymerase, 1.0 μL of DNA, and the remainder of 25 μL water. The ITS2 region was amplified with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for one min, followed by a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were cloned using the CloneJET PCR cloning kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) with the pJET1.2/blunt plasmid and β-select gold efficiency cells (Bioline). Colonies were picked and initially screened for inserts of the correct size with the pJET 1.2 Forward and Reverse sequencing primers. PCR screens of the correct size were treated with exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphatase [34] and sequenced at the University of Hawaii's Advanced Studies in Genomics, Proteomics, and Bioinformatics Facility.

To explore the potential association between coral and endosymbiont genotypes, the corals were genotyped using the NAD5 5' intron. Coral host DNA of the NAD5 5' mitochondrial intron was amplified and sequenced using protocols described in [29] and the primers NAD5_700F (5'-YTGCCGGATGCYATGGAG-3') and NAD1_157R (5'-VCCATCYGCAAAAGGCTG-3') [29].

Chromatograms of DNA sequences were inspected using Sequencher version 4.7 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and sequences were individually identified via the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) in GenBank. Symbiodinium sequences were manually aligned with the BioEdit version 5.0.9 sequence alignment software [35] and phylogenetically analyzed using statistical parsimony implemented in the program TCS version 1.21 [36]. Networks were delineated with 95% certainty, with gaps treated as a fifth state.

One potential problem associated with PCR based techniques is the overestimation of sequence diversity associated with the characterization of unique sequence types that reflect PCR error and/or intragenomic variation [37,38]. To address this and provide as conservative an estimate of biodiversity as possible, sequences included in the downstream analysis were screened for the following criteria: (1) sequences had either been published previously and the sequences retrieved and verified in multiple independent studies, or (2) were recovered in this study three or more times from clone libraries representing three or more independent coral samples. In addition, ITS2 folding was checked using previously published Symbiodinium ITS2 structures as templates [38,39] in the ITS2 database [40,41] and manually edited using the software 4SALE [42,43]. Potential pseudogenes were identified by significant changes to the 5.8S sequence not observed in Symbiodinium or in other closely related dinoflagellates [38] and changes to the secondary structure of the ITS2 RNA molecule likely to disrupt the functional fold.

A total of 246 sequences identified as Symbiodinium were recovered from 15 deep (67-100 m) Leptoseris spp. samples. Of the 68 unique sequence types, 55 were recovered only once and six were recovered twice; these 61 sequence types were dropped from the analysis. The secondary structure and folding analysis of the remaining seven sequence types identified a potential pseudogene that appeared non-functional (data not shown) and this was also dropped from the analysis. The number of excluded and included sequences are shown in Table 1. The six sequences retained for downstream analyses comprised 170 of the original 246 clones sequenced (69%).

All new sequences were submitted to GenBank and can be found under accession numbers FJ919240-FJ919245 for Symbiodinium and FJ919234-FJ919239 for Leptoseris.

Authors' contributions

YC obtained funding for the molecular analysis, collected the molecular data (including the DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and cloning of Leptoseris and Symbiodinium), conducted the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. XP helped with the molecular data collection and contributed extensively to the manuscript. MF obtained funding, helped with the molecular data collection, and edited the manuscript. DW collected the samples and contributed to the manuscript. GC contributed to the molecular data collection and edits to the manuscript. SK collected samples, obtained funding for sample collection, and commented on the manuscript. RT designed the study and helped revise the manuscript. RG designed the study and contributed extensively to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

NSF Hawaii EPSCoR provided funding and a REAP award to M. Fisher and Y. Chan. We thank members of the Toonen-Bowen and Gates labs, in particular Z. Szabo for lab guidance and M. Stat for folding analysis of ITS2. L. Hedouin provided assistance with the preliminary calculation of endosymbiotic dinoflagellate densities. We thank R. Grigg, R. Pyle and T. Montgomery for securing funding for the submersible dives and for providing samples. The captain and crew of R/V Kaimikai-o-Kanaloa provided surface support for all submersible operations and pilots Terry Kirby and Max Cremer provided superb skills in operating the submersible. This paper is a result of research funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coastal Ocean Program under award NA07NOS4780188 to the Bishop Museum, NA07NOS4780187 and NA07NOS478190 to the University of Hawaii, and NA07NOS4780189 to the State of Hawaii; and submersible support provided by NOAA Undersea Research Program's Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory. We also thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBGEA-115118 to X.P.) and the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at the University of Hawaii for financial support. This manuscript represents HIMB contribution #1363.

Contributor Information

Yvonne L Chan, Email: ylhchan@hawaii.edu.

Xavier Pochon, Email: pochon@hawaii.edu.

Marla A Fisher, Email: mfisher19@gmail.com.

Daniel Wagner, Email: wagnerda@hawaii.edu.

Gregory T Concepcion, Email: gregoryc@hawaii.edu.

Samuel E Kahng, Email: skahng@hpu.edu.

Robert J Toonen, Email: toonen@hawaii.edu.

Ruth D Gates, Email: rgates@hawaii.edu.

References

- Muscatine L, McCloskey LR, Muscatine RE. Estimating the daily contribution of carbon from zooxanthellae to coral animal respiration. Limnology and Oceanography . 1981;26:601–611. [Google Scholar]

- Muscatine L, Porter JW. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. BioScience. 1977;27:454–460. doi: 10.2307/1297526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatine L, McCloskey LR, Marian RE. Estimating the daily contribution of carbon from zooxanthellae to coral animal respiration. Limnology and Oceanography. 1981;26:601–611. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter D, Fricke HW, Weber W. Light harvesting by wavelength transformation in a symbiotic coral of the Red Sea twilight zone. Marine Biology. 1986;91:403–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00428634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maragos JE, Jokiel P. Reef corals of Johnston Atoll: one of the world's most isolated reefs. Coral Reefs. 1986;4:141–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00427935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng SE, Kelley CD. Vertical zonation of megabenthic taxa on a deep photosynthetic reef (50-140 m) in the Au'au Channel, Hawaii. Coral Reefs. 2007;26:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0253-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng SE, Maragos JE. The deepest zooxanthellate, scleractinian corals in the world? Coral Reefs. 2006;24:254. doi: 10.1007/s00338-006-0098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frade PR, Bongaerts P, Winkelhagen AJS, Tonk L, Bak RPM. In situ photobiology of corals over large depth ranges: A multivariate analysis on the roles of environment, host, and algal symbiont. Limnology and Oceanography. 2008;53:2711–2723. [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski PG, LaRoche J. Acclimation to spectral irradiance in algae. Journal of Phycology. 1991;27:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1991.00008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bythell JC, Douglas AE, Sharp VA, Searle JB, Brown BE. Algal genotype and photoacclimatory responses of the symbiotic alga Symbiodinium in natural populations of the sea anemone Anemonia viridis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1997;264:1277–1282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Prieto R, Trench R. Acclimation and adaptation to irradiance in symbiotic dinoflagellates. II. Response of chlorophyll-protein complexes to different photon-flux densities. Marine Biology. 1997;130:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s002270050221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coffroth MA, Santos SR. Genetic diversity of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium. Protist. 2005;156:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan R, Powers DA. Ribosomal RNA sequences and the diversity of symbiotic dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:3639–3643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochon X, Montoya-Burgos JI, Stadelmann B. Molecular phylogeny, evolutionary rates, and divergence timing of the symbiotic dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2006;38:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajeunesse TC. Investigating the biodiversity, ecology, and phylogeny of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium using the ITS region: in search of a "species" level marker. Journal of Phycology. 2001;37:866–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.01031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan R, Knowlton N. Intraspecific diversity and ecological zonation in coral-algal symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:2850–2853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frade PR, De Jongh F, Vermeulen F, Van Bleijswijk J, Bak RPM. Variation in symbiont distribution between closely related coral species over large depth ranges. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:691–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Prieto R, Trench R. Acclimation and adaptation to irradiance in symbiotic dinoflagellates. I. Responses of the photosynthetic unit to changes in photon flux density. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1994;113:163–175. doi: 10.3354/meps113163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bythell JC, Douglas AE, Sharp VA, Searle JB. Algal genotype and photoacclimatory responses of the symbiotic alga Symbiodinium in natural populations of the sea anemone Anemonia viridis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1997;264:1277–1282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stat M, Pochon X, Cowie ROM, Gates RD. Specificity in communities of Symbiodinium in corals from Johnston Atoll. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2009;386:83–96. doi: 10.3354/meps08080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lajeunesse TC, Thornhill DJ, Cox EF, Stanton FG, Fitt WK, Schmidt GW. High diversity and host specificity observed among symbiotic dinoflagellates in reef coral communities from Hawaii. Coral Reefs. 2004;23:596–603. doi: 10.1007/s00338-004-0428-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Prieto R, Beltrán V, Lajeunesse T, Reyes-Bonilla H, Thomé P. Different algal symbionts explain the vertical distribution of dominant reef corals in the eastern Pacific. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2004;271:1757–1763. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LR, Muscatine L. Production and respiration in the Red Sea coral Stylophora pistillata as a function of depth. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 1984;222:215–230. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke HW, Vareschi E, Schlichter D. Photoecology of the coral Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea twilight zone (an experimental study by submersible) Oecologia. 1987;73:371–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00385253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter D, Fricke HW. Mechanisms of amplification of photosynthetically active radiation in the symbiotic deep-water coral Leptoseris fragilis. Hydrobiologia. 1991;216/217:389–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00026491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houlbreque F, Ferrier-Pages C. Heterotrophy in tropical Scleractinian corals. Biological Reviews. 2009;84:1–17. doi: 10.1086/598251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mass T, Einbinder S, Brokovich E, Shashar N, Vago R, Erez J, Dubinsky Z. Photoacclimation of Stylophora pistillata to light extremes: metabolism and calcification. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;334:93–102. doi: 10.3354/meps334093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter D. A perforated gastrovascular cavity in the symbiotic deep-water coral Leptoseris fragilis: a new strategy to optimize heterotrophic nutrition. Helgoland Marine Research. 1991;45:423–443. doi: 10.1007/BF02367177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Concepcion GT, Medina M, Toonen RJ. Noncoding mitochondrial loci for corals. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2006;6:1208–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01493.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer TL, van Oppen MJH, Romano SL, Worheide G. Slow mitochondrial DNA sequence evolution in the Anthozoa (Cnidaria) Molecular Ecology. 2002;11:2475–2487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner D. Corals of Hawaii. Honolulu, HI: Mutual Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pochon X, Pawlowski J, Zaninetti L, Rowan R. High genetic diversity and relative specificity among Symbiodinium-like endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in soritid foraminiferans. Marine Biology. 2001;139:1069–1078. doi: 10.1007/s002270100674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pochon X, Garcia-Cuetos L, Baker AC, Castella E, Pawlowski J. One-year survey of a single Micronesian reef reveals extraordinarily rich diversity of Symbiodinium types in soritid foraminifera. Coral Reefs. 2007;26:867–882. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0279-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werle E, Schneider C, Renner M, Volker M, Fiehn W. Convenient single-step, one tube purification of PCR products for direct sequencing. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22:4354–4355. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Ac Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:1657–1660. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apprill AM, Gates RD. Recognizing diversity in coral symbiotic dinoflagellate communities. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:1127–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill D, Lajeunesse TC, Santos SR. Measuring rDNA diversity in eukaryotic microbial systems: how intragenomic variation, pseudogenes, and PCR artifacts confound biodiversity estimates. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:5326–5340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter RL, Lajeunesse TC, Santos SR. Structure and evolution of the rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region 2 in the symbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium, Dinophyta) Journal of Phycology. 2007;43:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selig C, Wolf M, Muller T, Dandekar T, Schultz J. The ITS2 Database II: homology modelling RNA structure for molecular systematics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;36:D377–D380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Muller T, Achtziger M, Seibel PN. The internal transcribed spacer 2 database--a web server for (not only) low level phylogenetic analyses. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:W704–707. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibel PN, Müller T, Dandekar T, Wolf M. Synchronous visual analysis and editing of RNA sequence and secondary structure alignments using 4SALE. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:91. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibel PN, Muller T, Dandekar T, Schultz J, Wolf M. 4SALE-a tool for synchronous RNA sequence and secondary structure alignment and editing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]