Abstract

We have reported a deficiency of a 91-kDa glycoprotein component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (gp91phox) in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes of a patient with X chromosome-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Sequence analysis of his gp91phox gene revealed a single-base mutation (C → T) at position −53. Electrophoresis mobility-shift assays showed that both PU.1 and hematopoietic-associated factor 1 (HAF-1) bound to the inverted PU.1 consensus sequence centered at position −53 of the gp91phox promoter, and the mutation at position −53 strongly inhibited the binding of both factors. It was also indicated that a mutation at position −50 strongly inhibited PU.1 binding but hardly inhibited HAF-1 binding, and a mutation at position −56 had an opposite binding specificity for these factors. In transient expression assay using HEL cells, which express PU.1 and HAF-1, the mutations at positions −53 and −50 significantly reduced the gp91phox promoter activity; however, the mutation at position −56 did not affect the promoter activity. In transient cotransfection study, PU.1 dramatically activated the gp91phox promoter in Jurkat T cells, which originally contained HAF-1 but not PU.1. In addition, the single-base mutation (C → T) at position −52 that was identified in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease inhibited the binding of PU.1 to the promoter. We therefore conclude that PU.1 is an essential activator for the expression of gp91phox gene in human neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes.

Keywords: gene expression, chronic granulomatous disease

Cytochrome b558 is a heterodimeric protein composed of the 91-kDa glycoprotein component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (gp91phox) (1–3) and p22phox (4), located in the plasma membrane of granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages (1), and B lymphocytes (5). When these cells are stimulated, cytochrome b558 forms a complex with cytosolic proteins such as the 47-kDa protein component of the oxidase (p47phox) (6–8), the 67 kDa protein component of the oxidase (p67phox) (9), 40 kDa protein component of the oxidase (p40phox) (10), and rac2 (11) and anchors a functional NADPH-dependent oxidase in the plasma membrane that generates superoxide anions (12, 13). The reactive oxygen species derived thereby are essential for microbial killing (14). The importance of the NADPH oxidase is emphasized by a genetic disorder known as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) (15), characterized by severe recurrent bacterial and fungal infections. Approximately 70% of CGD cases are the result of a defective gp91phox gene, located at Xp21.1 (1, 16, 17).

The gp91phox gene is exclusively expressed in terminally differentiated phagocytes and B lymphocytes, and therefore, its expression is regulated by cell-type- and development-specific mechanisms in hematopoietic cells. Analysis of its transcription mechanism is essential for a better understanding of inflammatory responses because it is regulated by various endogenous and exogenous inflammatory agents such as interferon γ (18–20) and lipopolysaccharides (19, 20).

Several transcriptional regulators that bind cis-elements of region between positions −450 and +12 of the gp91phox gene have been identified within the last 5 years. CCAAT displacement protein (CDP/cut) (21, 22) binds to four sites centered at positions −350, −220, −150, and −110 of the gp91phox promoter in undifferentiated myeloid cell lines, and its DNA binding activity is down-regulated in the terminal differentiation stage of those cell lines (23, 24). Furthermore, overexpression of cloned CDP prevents the induction of gp91phox expression during differentiation of those cell lines (25). Therefore, the down-regulation of the binding of CDP to the gp91phox promoter is necessary to induce gene transcription. However, this down-regulation is not sufficient to induce transcription, because the gene is not induced in CDP-down-regulated myotube cells (26). So, an additional activator is required for the expression of the gene.

Several transcriptional activators have been proposed for the gp91phox gene. CP1, one of CCAAT box binding proteins, and BID (binding increased during differentiation) associate with their binding sites. Because those binding sites and the CDP binding site are overlapping (23, 24, 27), CP1 and BID may bind after bound CDP has been released in the terminal differentiation of myeloid cell lines (23, 24). Therefore, these proteins are presumed to be activators for gp91phox gene transcription. Recently, it has been proposed that interferon regulatory factor 2 (IRF-2) may be a key activator for gp91phox gene expression (28). However, other essential activators should be participating in the expression of the gene, because these transcriptional activators are not sufficient, as shown in HeLa cells, which contain CP1 and IRF-2 but do not express gp91phox.

The discovery of a X chromosome-linked CGD patient with deficient expression of gp91phox in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes, but not in eosinophils (29), has stimulated us to look for a lineage-specific regulatory mechanism of the gp91phox gene expression. The patient had a natural mutation at position −53 that was involved in the binding site of hematopoietic-associated factor 1 (HAF-1) (30–32). Because HAF-1 has been assumed to be a transcriptional activator of the gene, we examined whether or not the binding of HAF-1 to its site is inhibited by the mutation.

Our data indicate that PU.1, rather than HAF-1, is a key activator of the gp91phox gene. The binding of PU.1 was also inhibited by the mutation at position −52, which was recently discovered in CGD patient with the same restricted gp91phox deficiency as that of the first patient. This type of CGD is defined as a PU.1 recruitment failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

X Chromosome-Linked CGD Patients.

The first patient was a 64-year-old man who suffered from many bacterial infections. Biochemical characterization of this CGD patient has been reported (29). The second patient was a 4-year-old boy with clinical symptoms similar to those observed in the first patient at young age. Clinical details of these patients will be presented elsewhere.

Leukocyte Isolations and Cell Cultures.

Peripheral blood from CGD patients and from healthy volunteers were obtained after informed consents had been given in accordance with either the Institutional Review Board of the School of Medicine, Nagasaki University, the Academic Hospital Maastricht, or the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Laboratory. Buffy coats were supplied by the Nagasaki Red Cross Blood Center (Nagasaki, Japan).

Neutrophils and mononuclear leukocytes (MNLs) were isolated from peripheral blood or buffy coats by using Conray/Ficoll as described (33). Monocytes and B lymphocytes were obtained from the MNLs by magnetic beads conjugated with anti-CD14 and anti-CD19 antibodies, respectively, according to the instructions of the manufacture (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch, Gladbach, Germany). T lymphocytes were purified from the MNLs by a rosetting procedure (34). Purities of separated neutrophils, monocytes, B lymphocytes, and T lymphocytes were >95%, 99%, 92%, and 90%, respectively, as determined by flow cytometry (FACScan, Becton Dickinson) with the use of cell-type-specific antibodies.

A human erythroleukemia cell line HEL (35), obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and a T cell leukemia cell line, Jurkat (36) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2.0 mM glutamine.

Amplification and Analysis of the gp91phox Promoter Region.

Genomic DNA was isolated from neutrophils and from Epstein–Barr virus-immortalized B cells with a commercially available kit, Genomix (TALENT, Trieste, Italy). The promoter region of the gp91phox gene was amplified by PCR with a set of primers that contain BamHI and XhoI restriction sites at their 5′ ends, as described by Dinauer et al. (37). The amplified fragments were inserted into BamHI–XhoI sites of pBluescript II (Stratagene), which was cloned and sequenced in both directions (38) with an Auto-read sequencing kit (Pharmacia/LKB) on a nonradioisotope sequencer, A.L.F. DNA Sequencer II (Pharmacia/LKB).

Construction of Expression Plasmids.

Normal and mutant (C → T at position −53; −53 mutant) fragments of the gp91phox promoter including positions −102 to +12 were constructed by PCR from genomic clones of a healthy individual and of the first X chromosome-linked patient as templates and a set of specific primers with HindIII and BamHI restriction sites at the 5′ termini of forward and reverse primers, respectively, as described by Luo et al. (24). Normal and −53 mutant reporter plasmids were made by cloning HindIII/BamHI digests of the corresponding PCR products into the HindIII–BglII sites of pXP2, a luciferase reporter gene vector (a gift from Y. Yamaguchi, Kumamoto University Medical School, Kumamoto, Japan) (39).

Two other mutant reporter plasmids were made with a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and complementary sets of 25-mer primers with single base mutations: Mutant gp91phox promoter fragments with single-base changes at positions −50 (to G) and −56 (to G) were excised from plasmids, sequenced, and cloned into the luciferase vector as above.

Human PU.1 cDNA excised with EcoRI from a vector (a gift from M. Klemsz, Indiana University, Indianapolis) was inserted into pBluescript II KS. A DNA fragment with forward orientation and another with reverse orientation were excised from plasmids by HindIII and BamHI and inserted into a pRC/CMV expression vector (Invitrogen).

Transient Expression Assays.

HEL cells (1 × 107 cells per 0.3 ml) suspended in RPMI 1640 medium were incubated with 10 μg of gp91phox promoter/firefly luciferase plasmid and 0.1 μg of cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-enhancer/renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL/CMV) (Toyoink, Tokyo) at room temperature for 15 min, electroporated at 950 μF and 240 V with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II, and cultured for 10 hr. Jurkat T cells (5 × 106 cells per 0.25 ml) were transfected by the electroporation with 5 μg of pRC/CMV expression vector with either an inserted sense or antisense human PU.1 and half the amount of the reporter plasmid used above and then cultured for 24 hr. The cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed on ice in 200 μl (HEL) or 100 μl (Jurkat) of lysis buffer (Toyoink). A 20-μl aliquot of 20 μl of the clarified lysate was used for assays of firefly and renilla luciferase activities with a PicaGene Dual SeaPansy luminescence kit (Toyoink) on a six-well luminometer, Berthold LB9505C (Berthold, Wildbad, Germany).

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from purified leukocytes and HEL cells as described by Schreiber et al. (40). Approximately 1 × 107 cells were swollen in 400 ml of ice-cold buffer A [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/10 mM KCl/0.1 mM EGTA/0.1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma)/2 μg of leupeptin (Sigma) per ml/2 μg of aprotinin (Sigma) per ml/10 μg of pepstatin A (Sigma) per ml/10 μg of 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml/10 μg of E-64-d (Peptide Institute, Osaka) per ml]. After a 15-min incubation at 4°C, the cells were lysed with 0.6% Nonidet P-40 and vortex-mixed vigorously for 10 sec. Supernatants were removed from lysates clarified by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 30 sec), and precipitates rich in nuclei were resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold buffer C (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/0.4 M NaCl/1 mM EGTA/1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/1 mM PMSF/2 μg of leupeptin per ml/2 μg of aprotinin per ml/10 μg of pepstatin A per ml/10 μg of 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin per ml/10 μg of E-64-d per ml). Nuclear extracts were separated by centrifugation (12,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min) and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad portein assay kit.

Electrophoresis Mobility-Shift Assays (EMSAs).

An EMSA probe was constructed by anealing the complementary pair of oligonucleotides identical to fragment from positions −68 to −30 of the human gp91phox and 32P 3′ end labeling with a dideoxyadenosine 5′-triphosphate (3′ end labeling kit, Amersham). BSA or nuclear extracts were preincubated without or with one of the competing double-stranded gp91phox oligonucleotides (positions −68 to −30) at 100- or 300-fold excess at 4°C for 15 min and were incubated with the probe (1 × 104 cpm) in a 20-μl reaction volume at 4°C for 20 min. Each mixture contained in common 5 μg of protein, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.01% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM spermidine, 2.0 μg of poly(dI⋅dC) (Pharmacia), and 1 pmol of single-stranded DNA with the wild-type sense sequence. Mixtures were loaded onto 3.4% polyacrylamide gels in 0.4× TBE (36 mM Tris borate, pH 8.3/0.8 mM EDTA) and electrophoresed at 4°C. The gel was dried and subjected to a CG-250 image analyzer (Bio-Rad).

For the inhibition of EMSA by an antibody, an aliquot of nuclear extract was incubated with 2.5 μl (2.5 μg) of rabbit anti-PU.1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or control IgG (Inter-cell Technologies, Hopewell, NJ) on ice for 1 hr before the addition of the radiolabeled probe.

Coding sequences of the probe and competitors are as follows. Lowercase type at 5′ or 3′ end indicates nucleotides added to facilitate cloning to plasmid vectors. Probe, 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATTTCCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGTa-3′; wild-type competitor, same as unlabeled probe; a heterologous competitor (30), 5′-GAAGCATAGTATAGAAGAAAGGCAAACACAACACATTCAa-3′; the CD11b PU.1-binding site competitor (41), 5′-CCTACTTCTCCTTTTCTGCCCTTCTTTGAG-3′; a −52 mutant competitor, 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATTTCTTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGTa-3′; a −53 mutant competitor, 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATTTTCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGTa-3′; a −55 mutant competitor (30), 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATCTCCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGTa-3′; a −57 mutant competitor (30), 5′-gatcCTGCTGTTTTCCTTTCCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGT-3′; the −50G mutant competitor, 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATTTCCTGATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGT-3′; and the −56G mutant competitor, 5′-CTGCTGTTTTCAGTTCCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAGT-3′.

RESULTS

C → T Base Change at Position −53 of the gp91phox Promoter in an X Chromosome-Linked CGD Patient.

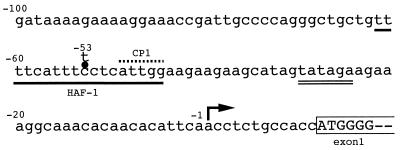

We previously reported deficient expression of gp91phox in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes but not in eosinophils of an X chromosome-linked CGD patient and proposed this deficiency to be the result of impaired gp91phox gene transcription in the former three types of leukocyte (29). Sequence analysis of its coding region identified no abnormalities but analysis of its promoter region showed a single-base mutation (C → T) at position −53 in the HAF-1-binding site (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Single-base C → T mutation at position −53 in the gp91phox promoter region of a CGD patient. HAF-1 binding site and a TATA-like sequence are indicated with a single underline and a double underline, respectively. The CP1 binding site is overlined. The transcription start site of the gp91phox gene is indicated by an arrow. The ORF is enclosed in a semi-open box.

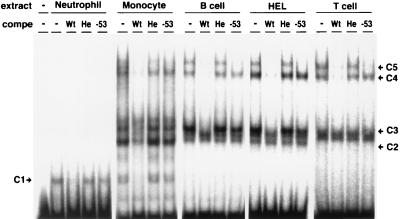

Nuclear Protein Complexes Whose Binding Is Inhibited by the CGD Mutation at Position −53 in Peripheral Leukocytes and HEL Cells.

To identify nuclear protein complexes whose binding to the gp91phox promoter region was inhibited by the mutation, EMSAs were performed with a probe spanning positions −68 to −30 of the gene and nuclear extracts from various types of normal peripheral leukocytes and HEL cells. As shown in Fig. 2, five complexes (C1–C5) bound to the probe specifically, because their binding was abolished by the wild-type competitor but not by a heterologous one. The binding of C1, C2, C3, and C4 to the probe was hardly inhibited by the competitor with the single C → T mutation at position −53 identified in our first patient (Fig. 1). Therefore, the binding of these four complexes was specific and severely inhibited by the mutation. C4 and C5 detected in all kinds of cells other than neutrophils were identified to be HAF-1 and CP1, respectively, based on their mobilities and sensitivities to competitors with single-base mutations at positions −55 and −57 (refs. 30 and 32). All the rest of the complexes are described in the following cells: C1 in neutrophils and monocytes, C2 in monocytes, and C3 in monocytes, B lymphocytes, and HEL cells.

Figure 2.

Specific binding of complexes C1, C2, C3, and C4 to the region from positions −68 to −30 of the gp91phox promoter are inhibited by the C → T mutation at position −53. The oligonucleotide probe including the gp91phox promoter region from positions −68 to −30 was used for EMSA. BSA (−) or nuclear extracts from various types of normal peripheral leukocytes were incubated without (−) or with the wild-type competitor (Wt), heterologous competitor (He), or −53 mutant competitor (−53) at 300-fold molar excess.

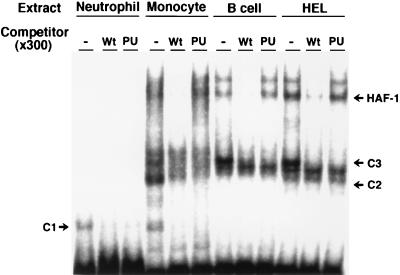

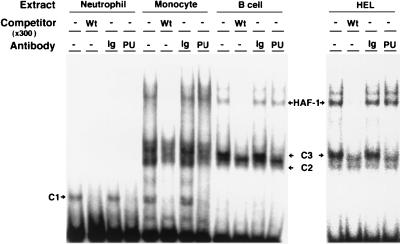

PU.1 as the DNA-Binding Component in Complexes C1, C2, and C3.

Position −53 is located in an inverted Ets core sequence (5′-GGA-3′, second G is complementary to normal −53C) (42), suggesting that complexes C1, C2, and C3 include a member of the Ets family. Because PU.1 is commonly expressed in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes (41), it seemed likely that these complexes contain PU.1. To test this possibility, we used the −26 to +1 fragment of the CD11b promoter as a competitor because it contains the PU.1-binding consensus sequence (Fig. 3). The fragment competitor (PU) completely abolished binding of all these three complexes to the probe as did the wild-type competitor. In addition, gel-shift immunoassays performed with an anti-PU.1 antibody demonstrated that the antibody also specifically abolished the binding of all three complexes (Fig. 4). These results indicate that PU.1 is a common DNA-binding component of C1, C2, and C3. The different mobilities among the complexes may reflect their different protein members, such as NF-EM5 (43) in B lymphocytes, and/or unavoidable partial degradation of PU.1 during the preparation of nuclear extracts.

Figure 3.

Binding of complexes C1, C2, and C3 to the gp91phox promoter region are competed by the consensus PU.1 binding sequence. The oligonucleotide probe including the gp91phox promoter region from positions −68 to −30 was used for competition assays. Nuclear extracts (5 μg) from various types of peripheral leukocytes were preincubated without (−) or with the wild-type competitor (Wt) or CD11b PU.1 binding-site competitor (PU) at 300-fold molar excess and were incubated with the probe.

Figure 4.

Anti-PU.1 antibody specifically abolishes binding of complexes C1, C2, and C3 but not that of HAF-1 or CP1 to the gp91phox proximal promoter. BSA (−) or each nuclear extract was preincubated in the absence or presence of 2.5 μg of anti-PU.1 antibody (PU) or control rabbit Ig (Ig) and was incubated with the same probe as used in Fig. 3. Wt and − in the line of competitor indicate wild-type competitor and no competitor, respectively.

PU.1 as a Key Activator for the Expression of gp91phox Gene.

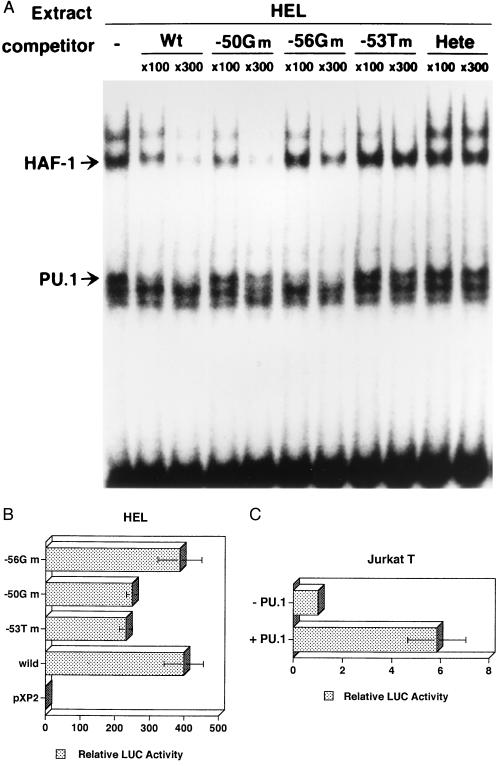

To analyze roles of PU.1 and HAF-1 in the gp91phox gene expression, we searched for mutations that individually inhibit the binding of PU.1 and HAF-1 by using various competitors with single-base mutations around position −53. As shown in Fig. 5A, the competitor with G at position −50 (−50Gm) effectively inhibited the binding of HAF-1 as the wild-type competitor but not that of PU.1, indicating that the −50G mutation preferentially eliminates a PU.1-binding activity from the gp91phox promoter. On the other hand, the competitor with G at −56 (−56Gm) effectively inhibited the binding of PU.1 as the wild-type competitor but not that of HAF-1, indicating the −56G mutation to preferentially eliminate a HAF-1-binding activity from the promoter.

Figure 5.

PU.1 is a key activator for the expression of the gp91phox gene. (A) Two single-base mutant competitors, −50G mutant (−50Gm) and −56G mutant (−56Gm), with G at positions −50 and −56, instead of wild-type C and T, respectively, were used in EMSA, as in Fig. 2. (B) Each reporter plasmid with −50G mutant, −56G mutant, −53T CGD mutant, or wild-type gp91phox promoter was transiently expressed in HEL cells. Relative activities of −53T mutant promoter and −50G mutant one are significantly lower than those of the wild-type promoter and −56G mutant one (P < 0.05). (C) PU.1 increases gp91phox proximal promoter activity in Jurkat cells (P < 0.01). Jurkat T cells were transfected with either one of sense and antisense PU.1 vectors and the wild-type gp91phox promoter-reporter plasmid.

We examined the effects of the −53T, −50G, and −56G mutations on the gp91phox promoter activity using a transient expression assay system. A luciferase reporter gene was connected to the gp91phox promoter (positions −102 to +12) with the wild-type sequence or with the sequence having either one of these mutations and was transfected into HEL cells. The HEL cells express PU.1 and HAF-1 (Figs. 2, 3, and 4), and this promoter region exhibits a high promoter activity in the cells (24, 28). As shown in Fig. 5B, the construct with the wild-type promoter sequence exhibited 400-fold the activity of that of a promoter-less construct. This activity was significantly reduced to 57% by the −53 CGD mutation (P < 0.05), indicating the mutation to be inhibitory to the transcription of gp91phox gene. The activity of the −50Gm mutant promoter was as low as that of the −53T mutant promoter, but the activity of the −56Gm mutant promoter was as high as that of the wild-type promoter. Therefore PU.1 has a role as a key activator in the gp91phox gene expression. To confirm the activator function of PU.1, we transfected PU.1 expression vector with the gp91phox promoter construct containing positions −102 to +12 into Jurkat T cells, in which PU.1 but not HAF-1 was primarily deficient (data not shown). When PU.1 was expressed (Fig. 5C), the wild-type promoter activity increased 6-fold compare to that in the absence of PU.1 (P < 0.01), confirming PU.1 to be a key activator for the expression of the gp91phox gene.

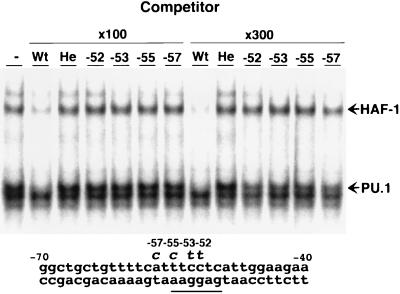

A Single-Base Mutation at Position −52 Identified in the Second CGD Patient Inhibits PU.1 Binding to gp91phox Promoter as Mutations at Positions −53, −55, and −57.

We discovered a second CGD patient with the single-base mutation (C → T) at position −52 of the gp91phox promoter whose phenotypic pattern of gp91phox expression in peripheral leukocytes was similar to that of our first patient (J. Schrander, R. Neefjes, and D.R., unpublished results); surface cytochrome b558 was deficient in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes but not in eosinophils. Because its mutation site is 1 base downstream of the position of the first mutation and is involved in the consensus sequence for the binding of PU.1, we used an EMSA to determine whether this mutation also inhibits the binding of PU.1 to the gp91phox promoter. As shown in Fig. 6, the competitor with this mutation failed to inhibit the binding of PU.1 to the wild-type probe, indicating that the mutated promoter of the patient does not recruit PU.1 as did the promoter of the first patient. Therefore, we conclude that PU.1 is an essential activator for the expression of gp91phox gene in human neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes. Other competitors with single-base mutations at positions −55 and −57, reported in other CGD patients (30, 32), also failed to inhibit the binding (Fig. 6), which is consistent with the deficient expression of the gene in most, if not all, neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes of these CGD patients.

Figure 6.

Competitor with single-base C → T mutation at position −52, which was identified in a CGD patient fails to inhibit the binding of PU.1 to the gp91phox promoter, as do those with single-base mutations at positions −53, −55, and −57. Competitive EMSA were performed in the presence or absence of 100- or 300-fold molar excess of one of following competitors; −52 CGD mutant competitor (−52G), −53 CGD mutant competitor (−53), −55 CGD competitor (−55), and −57 CGD competitor (−57). Mutations in the latter two competitors have been reported by Newburger et al. (30). The gp91phox promoter region from positions −70 to −40 is indicated at the bottom. PU.1 consensus sequence (46) is underlined.

DISCUSSION

We report that PU.1 binds to the inverted PU.1 consensus sequence (Pu box) (42) of the proximal promoter region of the gp91phox gene in peripheral neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes as an essential activator of the gene. The binding of PU.1 to the sequence is inhibited by single-base mutations at positions −53, −52, or −50, which were identified in our X chromosome-linked CGD patients or in in vitro experiments. The CGD patients exhibited significantly reduced gp91phox expression in neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes (ref. 29, and J. Schrander, R. Neefjes, T. Kondoh, and D.R., unpublished observations). It should be noted that the phenotype of CGD observed in our patients is a naturally occurring disease with deficient recruitment of PU.1 to a gene. PU.1 null mice could not express gp91phox gene (B. E. Torbett, personal communication), suggesting PU.1 to be essential activator of gp91phox gene in mice. PU.1 is also essential for the expression of human p47phox (44), a soluble component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase, implying PU.1 is a common transcriptional activator for the expression of the oxidase in phagocytes and B lymphocytes.

The presence of PU.1 was not clear in eosinophils. But the binding of PU.1 to the Pu box is not essential for the expression of gp91phox in human eosinophils. An eosinophil-specific activation mechanism is, therefore, expected, for which we are now searching.

Enhancement of gp91phox gene expression by interferon γ has been reported in peripheral neutrophils and monocytes (18–20). Recently Eklund and Skalnik (32) reported that interferon γ-induced transcription at the −450 to + 12 gp91phox promoter region in PLB985 cells (a myelogenous cell line) was abolished by the −57 CGD mutation (32). In conjunction with our present results, these findings strongly suggest that PU.1 has a key role in the interferon γ-induced expression of gp91phox. This hypothesis is supported by a report indicating that the binding of PU.1 to the major histocompatibility complex class II I-Ab promoter region was accelerated by interferon γ in murine peripheral macrophages (45). They reported that overexpression of IRF-2 transactivates the −102 to +12 gp91phox promoter in HEL and K562 cell lines (28), suggesting a role for IRF-2 in gp91phox expression. Although IRF-2 may participate in the induction of gp91phox via interferon γ in monocytes, it is poorly expressed in quiescent peripheral monocytes (46), which significantly express gp91phox gene expression. Therefore, IRF-2 is unlikely to direct basal expression of gp91phox in monocytes.

In the transient transfection assay, the activity of the gp91phox promoter region spanning positions −102 to +12 is reduced to half by the −53 CGD mutation in HEL cells (Fig. 5B). But the content of gp91phox mRNA in neutrophils and monocytes of the patient with this mutation is less than 10% of the control cells (29). These facts suggest that the PU.1 bound to Pu box also mediates other activation mechanism(s) of gp91phox gene by cis-elements located outside the promoter region from positions −102 to +12.

How does PU.1 activate the gp91phox gene? PU.1 associates with several factors, such as TATA-binding protein (43, 47, 48). Therefore, one possibility is that PU.1 promotes the binding of basal transcriptional factors to the TATA-like sequence (positions −30 to −25) of the gene. Analysis of PU.1 association factors should lead to additional mechanisms of the gp91phox gene expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. T. Moriuchi and Mr. M. de Boer for their assistance in DNA sequencing and Dr. M. Klemsz (Indiana University) for providing us with the PU.1 cDNA. We thank Dr. S. H. Orkin (Harvard Medical School) for kind permission to use unpublished sequences of primers for PCR of gp91phox exons. We also thank Dr. S. Kanegasaki (Tokyo University) and Dr. W. M. Nauseef and Dr. F. DeLeo (University of Iowa) for valuable discussion and review of this manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid of the Ministry of Japan for Education, Science, Culture, and Sports, a grant for Center of Excellence, and Grant for Cooperation Research of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University. In addition, grants were obtained from the Netherlands Foundation for Preventive Medicine (Preventiefounds) and for the European Biomed concerted action (PL 96300F).

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: gp91phox, 91-kDa glycoprotein component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase; p47phox, 47-kDa protein component of the oxidase; p67phox, 67-kDa protein component of the oxidase; p40phox, 40-kDa protein component of the oxidase; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; HAF-1, hematopoietic-associated factor 1; CDP, CCAAT displacement protein; BID, binding increased during differentiation; IRF-2, interferon regulatory factor 2; EMSA, electrophoresis mobility-shift assay.

References

- 1.Royer P B, Kunkel L M, Monaco A P, Goff S C, Newburger P E, Baehner R L, Cole F S, Curnutte J T, Orkin S H. Nature (London) 1986;322:32–38. doi: 10.1038/322032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinauer M C, Orkin S H, Brown R, Jesaitis A J, Parkos C A. Nature (London) 1987;327:717–720. doi: 10.1038/327717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teahan C, Rowe P, Parker P, Totty N, Segal A W. Nature (London) 1987;327:720–721. doi: 10.1038/327720a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkos C A, Dinauer M C, Walker L E, Allen R A, Jesaitis A J, Orkin S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3319–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi S, Imajoh O S, Nakamura M, Kanegasaki S. Blood. 1990;75:458–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunoi H, Rotrosen D, Gallin J I, Malech H L. Science. 1988;242:1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.2848319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpp B D, Nauseef W M, Donelson J E, Moser D R, Clark R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7195–7199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lomax K J, Leto T L, Nunoi H, Gallin J I, Malech H L. Science. 1989;245:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.2547247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leto T L, Lomax K J, Volpp B D, Nunoi H, Sechler J M, Nauseef W M, Clark R A, Gallin J I, Malech H L. Science. 1990;248:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1692159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wientjes F B, Hsuan J J, Totty N F, Segal A W. Biochem J. 1993;296:557–561. doi: 10.1042/bj2960557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leto T L, Lomax K J, Volpp B D, Nunoi H, Sechler J M, Nauseef W M, Clark R A, Gallin J T, Malech H L. Science. 1990;248:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1692159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumimoto H, Hata K, Mizuki K, Ito T, Kage Y, Sakaki Y, Fukumaki Y, Nakamura M, Takeshige K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22152–22158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLeo F R, Quinn M T. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;60:677–691. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curnutte J T. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67:S2–S15. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos D, de Boer M, Kuribayashi F, Meischl C, Weening R S, Segal A W, Ahlin A, Nemet K, Hossle J P, Bernatowska-Matsuzkiewicz E, Middleton-Price H. Blood. 1996;87:1663–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francke U, Ochs H D, de Martinville B, Giacalone J, Lindgren V, Disteche C, Pagon R A, Hofker M H, van Ommen G J, Pearson P L, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:250–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baehner R L, Kunkel L M, Monaco A P, Haines J L, Conneally P M, Palmer C, Heerema N, Orkin S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3398–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newburger P E, Ezekowitz R A, Whitney C, Wright J, Orkin S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5215–5219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassatella M A, Bazzoni F, Flynn R M, Dusi S, Trinchieri G, Rossi F. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20241–20246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newburger P E, Dai Q, Whitney C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16171–16177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blochlinger K, Bodmer R, Jack J, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Nature (London) 1988;333:629–635. doi: 10.1038/333629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neufeld E J, Skalnik D G, Lievens P M, Orkin S H. Nat Genet. 1992;1:50–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skalnik D G, Strauss E C, Orkin S H. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16736–16744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo W, Skalnik D G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18203–18210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lievens P M, Donady J J, Tufarelli C, Neufeld E J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12745–12750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andres V, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Development. 1992;116:321–334. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eklund E A, Luo W, Skalnik D G. J Immunol. 1996;157:2418–2429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo W, Skalnik D G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23445–23451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuribayashi F, Kumatori A, Suzuki S, Nakamura M, Matsumoto T, Tsuji Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:146–152. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newburger P E, Skalnik D G, Hopkins P J, Eklund E A, Curnutte J T. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1205–1211. doi: 10.1172/JCI117437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodman R C, Newburger P E, Anklesaria P, Erickson R W, Rae J, Cohen M S, Curnutte J T. Blood. 1995;85:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eklund E A, Skalnik D G. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8267–8273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyum A. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;21:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek E M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Greene and Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin P, Papayannopoulou T. Science. 1982;216:1233–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.6177045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillis S, Watson J. J Exp Med. 1980;152:1709–1719. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.6.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinauer M C, Curnutte J T, Rosen H, Orkin S H. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:2012–2016. doi: 10.1172/JCI114393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger F, Air G M, Barrell B G, Brown N L, Coulson A R, Fiddes C A, Hutchison C A, Slocombe P M, Smith M. Nature (London) 1977;265:687–695. doi: 10.1038/265687a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordeen S K. Biotechniques. 1988;6:454–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller M M, Schaffner W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H M, Zhang P, Voso M T, Hohaus S, Gonzalez D A, Glass C K, Zhang D E, Tenen D G. Blood. 1995;85:2918–2928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wasylyk B, Hahn S L, Giovane A. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:7–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78757-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pongubala J M, Van B C, Nagulapalli S, Klemsz M J, McKercher S R, Maki R A, Atchison M L. Science. 1993;259:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.8456286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S L, Valente A J, Zhao S J, Clark R A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17802–17809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shackelford R, Adams D O, Johnson S P. J Immunol. 1995;154:1374–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayes M P, Zoon K C. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3222–3227. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3222-3227.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagemeier C, Bannister A J, Cook A, Kouzarides T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1580–1584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagulapalli S, Pongubala J M, Atchison M L. J Immunol. 1995;155:4330–4338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]