Abstract

Purpose

Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, enhances cell death by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in vitro. We sought to test the combination clinically.

Experimental Design

A phase I trial evaluated sequential dose escalation of bortezomib at 1– 1.3 mg/ m2 intravenously on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 and vorinostat at 100–500 mg orally daily for 8 days of each 21-day cycle in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients. Vorinostat pharmaco-kinetics and dynamics were assessed.

Results

Twenty-three patients were treated. Patients had received a median of 7 prior regimens (range: 3–13), including autologous transplantation in 20, thalidomide in all 23, lenalidomide in 17, and bortezomib in 19, 9 of whom were bortezomib-refractory. Two patients receiving 500 mg vorinostat had prolonged QT interval and fatigue as dose-limiting toxicities. The most common grade ≥3 toxicities were myelo-suppression (n=13), fatigue (n=11) and diarrhea (n=5). There were no drug-related deaths. Overall response rate was 42%, including 3 partial responses among 9 bortezomib refractory patients. Vorinostat pharmacokinetics were non-linear. Serum Cmax reached a plateau above 400 mg. Pharmacodynamic changes in CD-138+ bone marrow cells pre- and on day 11 showed no correlation between protein levels of NF-κB, IκB, acetylated tubulin and p21CIP1 and clinical response.

Conclusions

The maximum tolerated dose of vorinostat in our study was 400 mg daily for 8 days every 21 days, with bortezomib administered at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. The promising anti-myeloma activity of the regimen in refractory patients merits further evaluation.

Keywords: Vorinostat, Bortezomib, Multiple Myeloma

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma is an incurable plasma cell malignancy. In the United States, there are 19,920 estimated new cases of multiple myeloma and 11,190 deaths annually.(1) Autologous transplantation and the introduction of thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide have improved treatment outcomes. However, despite initial response to various therapies, almost all patients relapse and become refractory to subsequent treatment. Responses are uncommon in refractory myeloma patients, and median survival is less than 12 months after failure of 2 or more salvage therapies.(2)

The clinical activity of bortezomib in multiple myeloma is well established. Possible mechanisms of bortezomib activity include diminished nuclear localization of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) due to inhibition of proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated inhibitor of κB (IκB).(3–5) NF-κB mediates key cellular functions, including growth, survival, and apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells and may play a role in chemo-resistance.(6–9) Cells exposed to bortezomib form aggregates of ubiquitin-conjugated proteins, or "aggresomes", in vitro and in vivo.(10) Bortezomib-induced aggresome formation may serve a cytoprotective role by allowing cells to dispose of accumulated unfolded proteins that result from proteasome dysfunction.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors regulate gene expression through epigenetic modulation of chromatin structure.(11) HDACIs also affect other cellular functions through up-regulation of death receptors, induction of oxidative injury, and disruption of chaperone protein function.(12) Notably, HDACIs, inhibit HDAC6 function and disrupt aggresome formation.(13, 14) These events result in endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of apoptosis in vitro.(15)

In multiple myeloma cells, bortezomib and tubacin, an experimental HDACI that specifically inhibits HDAC6 and triggers the acetylation of α-tubulin, exhibited highly synergistic interactions.(16) The combination induced significant cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma cells isolated from patients’ bone marrow and in adherent multiple myeloma cells, which are known to be resistant to conventional treatments. The relative contributions of NF-κB inhibition versus disruption of aggresome function in synergistic interactions between proteasome and HDAC inhibitors in multiple myeloma are unknown. The combination of bortezomib and vorinostat also diminished NF-κB activation and induction of p21CIP1, as was first described by Mitsiades, et al. (6) Later studies have shown that HDACIs can increase expression of NF-κB and that acetylation of p65/RelA promotes DNA binding and activation. Conversely, inhibition of NF-κB by IKK inhibitors diminishes nuclear translocation and activation, resulting in down-regulation of NF-κB-dependent survival genes such as XIAP and Bcl-xL.(17) Therefore, bortezomib may increase HDACI lethality by opposing NF-κB activation induced by p65/RelA acetylation. A recent study showed synergistic interactions between bortezomib and HDACIs in CLL cells in association with NF-κB inactivation and XIAP/Bcl-xL down-regulation.(18)

Although a phase I trial of vorinostat failed to establish significant single-agent activity in relapsed and refractory myeloma patients, it did show favorable tolerability and evidence of disease stabilization in this heavily pre-treated population.(19) Based upon informative preclinical data and the encouraging safety profile defined in the phase I monotherapy setting, we hypothesized that vorinostat may be clinically synergistic with bortezomib, especially in bortezomib-refractory patients, and that this combination therefore warranted study. A multi-center phase I trial was initiated to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of vorinostat in combination with bortezomib in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Secondary objectives were to define the pharmacokinetics of vorinostat when administered in combination with bortezomib, to assess the biological effects of vorinostat on bone marrow plasma cells, and to evaluate anti-tumor activity. Biological effects of vorinostat studied included measurement of protein levels of NF-κB, IκB, acetylated tubulin and p21CIP1. Additionally, expression of phosphorylated eIF2α and levels of NF-κB-dependent anti-apoptotic proteins, including Bcl-xl and XIAP, were evaluated for their potential utility as surrogate markers for response in future trials.(20, 21)

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Eligibility

Patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma were eligible. Patients had to have received at least 3 lines of prior therapies that could have included conventional and high-dose chemotherapy, as well as novel investigational agents. Patients were required to have measurable disease at study entry. Patients could not have received therapy for at least 2 weeks prior to study entry. Patients had to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status score of ≤2 and a life expectancy > 6 months. Patients were excluded if they had abnormal liver function (bilirubin, AST or ALT > twice the upper limit of normal) or inadequate marrow function as defined by an absolute neutrophil count < 1000/ml or a platelet count < 50,000/ml, except if myelosuppression was attributed to marrow plasmacytosis (defined by > 80% plasmacytosis). Patients were allowed to receive growth factors. Patients had to have a serum creatinine < 2 mg/dL or a creatinine clearance > 40 ml/min by 24-hour urine collection. Patients with grade II or higher peripheral neuropathy were excluded. Women of childbearing potential and all men agreed to use adequate contraception during study participation. The Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the participating sites approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Design

Therapy was administered on an outpatient basis. Bortezomib was delivered at 1–1.3 mg/m2 intravenously over 3–5 seconds on days 1, 4, 8 and 11. Vorinostat was administered orally one hour after bortezomib on days 4–11. The vorinostat dose regimens evaluated were 100 mg twice daily, 200 mg twice daily, 400 mg once daily and 500 mg once daily. Cycles were repeated every 21 days and continued for a total of 8 cycles or until disease progression, occurrence of unacceptable adverse events or if the patient withdrew consent. Patients removed from study for unacceptable adverse events were followed until resolution or stabilization of the adverse event. After 2 cycles, dexamethasone was allowed at 20 mg orally daily for 5 days (days 4–8) in patients with less than a partial remission, for a total dose of 100 mg/cycle. All patients were to receive antiviral prophylaxis. Anti-diarrheal therapy was prescribed if diarrhea occurred.

Three patients were enrolled in each cohort; dose escalation proceeded if there were no dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) in the first cycle. If 1 of 3 patients experienced DLT in cycle 1, dose escalation was stopped, and 3 additional patients were enrolled into the cohort. The dose was not escalated if 2 of 3–6 patients in a cohort experienced DLT. DLT was defined as any grade 3, or higher, non-hematological toxicity excluding grade 3 fatigue unless persisting for 7 days after stopping vorinostat. Any grade 4 hematological toxicity that persisted for ϧ days was considered a DLT except for thrombocytopenia that responded to transfusion support. The MTD was the highest dose that produced ≤ 1 DLT in a cohort of 6 patients.

If grade 2 or higher toxicity was suspected to be due to bortezomib, the drug was held until the toxicity resolved and then re-started at 1 mg/m2. If toxicity recurred, the subsequent dose of bortezomib was decreased to 0.7 mg/m2. If toxicity did not resolve to < grade 2 within 2 weeks of onset or recurred on 0.7 mg/m2 of bortezomib, the patient was removed from the study. The vorinostat dose was decreased by 50% for each toxicity grade, and was stopped if the lowest vorinostat dose of 100 mg daily was not tolerated. For overlapping toxicities such as hematological and gastrointestinal, bortezomib was decreased first.

Pretreatment evaluation included a complete history and physical examination, ECOG performance status, complete blood counts, electrolytes, hepatic, renal, and thyroid function tests, urinalysis, pregnancy test (if appropriate), chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, bone marrow examination and computerized tomography scan for patients with extramedullary disease. Adverse events were graded according to the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (CTCAE version 3.0; http://ctep.info.nih.gov). Any grade 3 or 4 non-hematological toxicity was reported to the IRB and the NCI. Multiple myeloma response and progression were assessed using International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. (22)

Vorinostat and bortezomib were provided by Merck & Co., Inc, (Whitehouse Station, NJ) and Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Company Inc, (Cambridge, MA), respectively, through the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, which supported the trial. Patients were treated at two centers, University of Maryland (n=21) and Cornell (n=2).

Pharmacokinetic studies

Twenty-one patients had blood samples drawn on day 4 of cycle 1 to characterize the pharmacokinetics of orally administered vorinostat. Five mL of blood were collected, without anticoagulant, before and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 hours after oral administration of vorinostat. Blood samples were allowed to clot at 4°C for 20–30 min and then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The serum was stored at −70°C until assayed for drug content. Vorinostat concentrations in serum were quantified by a validated liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric method.(23) The maximum serum vorinostat concentration (Cmax) and time to reach the maximum concentration (tmax) were determined by visual inspection of serum vorinostat concentration versus time curves. The Lagrange function(24), as implemented by the LAGRAN computer program (25), was used for non-compartmental estimation of the area under the vorinostat serum concentration versus time curve (AUC), with extrapolation to infinity, and for estimation of vorinostat half-life (t1/2). The AUC was used to calculate clearance (CL/F), which was defined as dose/AUC. Statistical analyses for pharmacokinetics were performed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The relationship between vorinostat dose and Cmax was evaluated with the Student t-test. The relationship between vorinostat dose and CL/F was evaluated with linear regression. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Pharmacodynamic Studies

Isolation of myeloma cells from bone marrow

Bone marrow aspirates (5–10 mL) were obtained from patients at baseline (day 1) and on day 11 of the first cycle of therapy, 2–3 hours after both drugs were given. Multiple myeloma cells were isolated by using a magnetic cell sorter (MACS) and anti-CD138 antibody-coated magnetic micro-beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), as described previously.(26, 27) Bound (CD138+) and unbound cell fractions were collected, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and pelleted. Approximately 50,000 cells were diluted into 300 µL PBS and used to prepare cytospins with a Shandon Cytospin I centrifuge (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The remaining cells were pelleted and frozen at −80°C for subsequent Western blot analysis.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Frozen CD138+ cell pellets were resuspended in ice cold cell lysis buffer containing a final concentration of 4 mM Tris-Hcl pH7.5, 30 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA. 0.2% Triton, 0.2 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 0.2 mM beta-glycerophosphate with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) and sonicated using a Misonix sonicator 3000. Total cellular protein was quantified using a Biorad protein assay. Protein (30–50 mg) was loaded onto a 4–12% NuPAGE® gels and separated using a NuPAGE® Novex® bis-tris gel electrophoresis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Each blot was divided into two membranes depending on the molecular weight of the proteins to be probed, using Anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the loading controls for the analysis. Phospho-eIF2α (Ser51) rabbit mAb, phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36) mouse monoclonal Ab and BclxL polyclonal rabbit antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), PARP mouse monoclonal antibody from BIOMOL International Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA), Bcl2 mouse monoclonal antibody from DAKO North America Inc. (Carpinteria, CA), p21CIP1 and XIAP monoclonal antibodies from BD Transduction Labs (San Jose, CA) and NFκ B/p65 subunit polyclonal antibodies from Millipore (Danvers, MA) were used. Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-labeled affinity-purified antibodies to rabbit and mouse IgG from KPL (Gaithersburg, MD). Signals were detected by enhanced chemi-luminescence (SuperSignal WestPico chemiluminescent substrate, Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL), and quantitative analysis was performed using the FluoChem 8800 Imaging System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Two-dimensional spot densitometric images were obtained and analyzed with Alpha Ease FC software (Alpha Innotech). Each protein band on the Western blots was assigned an average pixel value from a scale of 1–200 adjusted to arbitrary unit 1 in pre samples. Changes in protein expression were normalized to the loading control protein (GAPDH) to determine the percent increase or decrease.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Twenty-three patients were enrolled between June 2006 and October 2007; the final analysis was carried out in July 2008. Demographics, disease characteristics, and baseline laboratory values are shown in Table 1. All patients had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. All patients were heavily pre-treated for multiple relapses. The median number of prior regimens was 7 (range: 3–13). Twenty patients had had prior autologous stem cell transplantation, including 6 who received tandem transplants, and one who also had an allogenic transplant. All 23 patients had received thalidomide, 11 as maintenance after transplantation and 12 for relapsed disease; of the latter group, 5 were refractory. Nineteen patients had received bortezomib; the median number of bortezomib-containing regimens was 2 (range: 1–3). Nine patients were bortezomib-refractory and 10 had progressive disease after an initial response lasting a median of 6 months (range: 3–35) and 4 were bortezomib-naïve. Seventeen patients had received lenalidomide, among whom 9 were refractory and 8 progressed after an initial response lasting a median of 4 months (3–18). Overall, 16 patients were refractory to their last therapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| No. | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (39–78) | |

| Sex: Male/female | 15 / 8 | |

| Race: Caucasian/Blacks | 18 / 5 | |

| Isotype: Ig G/A/LC | 11 / 4 / 8 | |

| No of Prior Regimens | 7 (3–13) | |

| SCT-Autologous/Tandem/Allo | 20 / 6/ 1 | |

| Prior Thalidomide / Lenalidomide | 23 / 17 | |

| Bortezomib | 19 | |

| Duration (months) | 6 (2–40) | |

| No. of regimens 1/2/3 | 8 / 5 / 6 | |

| Primary refractory | 9 | |

| Responsive then progressive | 10 | |

| ECOG | 1 (0–2) | |

| Time from diagnosis to study (years) | 5.7 (1.8 – 9) | |

| Time from last therapy (days) | 20 (15 –39) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.3 (0.7 – 2.1) | |

| Hgb (g/dl) | 11 (8.5 – 14) | |

| Platelets (×103/ul) | 148 (62 – 253) | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.8 (2.5 –4.7) | |

| LDH (Units/L) | 209 (104 – 619) | |

| Beta-2-microglobulin (mg/L) | 3 (1.3 – 6) | |

| Baseline Peripheral neuropathy | 13 | |

| Grade 1 / 2 | 11 / 2 | |

| Abnormal karyotype | 14 | |

| 11;14 | 6 | |

| Hypodeploidy: del(13), del(17) | 7/3 | |

| Dup, der, del(1) | 9 | |

Patients were treated at 5 dose levels. Three patients were treated with bortezomib 1.0 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8 and 11, with 8 days of vorinostat 100 mg twice daily. The bortezomib dose was then escalated to 1.3, with 8 days of vorinostat at doses of 100 mg (n=3) and 200 mg (n=3) twice daily, and 400 mg (n=3) and 500 mg (n=3) once daily. Eight patients were then treated at the MTD to better define toxicity and efficacy. A total of 112 cycles of therapy were administered, with a median of 3 cycles per patient (range: 1–8). Three patients completed the maximum allowed eight cycles of therapy.

Safety and tolerability

DLTs occurred in 2 patients treated at the vorinostat 500 mg dose. One DLT was grade 3 fatigue and the other was prolongation of the corrected QT interval. The MTD for the combination was 400 mg of vorinostat administered oral daily for 8 days with bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 given on days 1, 4, 8 and 11, with cycles repeated every 21 days.

The most common drug-related adverse events and laboratory abnormalities observed in cycle 1 were diarrhea (52%), nausea (48%), fatigue (35%), peripheral neuropathy (57%), and increased creatinine (30%). These events were mostly grades 1 and 2. Hematological toxicities including thrombocytopenia (52%), anemia (30%) and neutropenia (17%) were reversible, with no bleeding or life-threatening infections. Once CTEP reported on prolonged QT interval in patients receiving vorinostat on other trials, we monitored patients entering the trial with electrocardiograms 3 hours after vorinostat administration. Ten patients had electrocardiograms at baseline and after vorinostat. Prolongation of QTc was noted in 9 patients, all on 400 mg daily, and was grade 1 in 7 and grade 2 in 2,. One patient had grade 3 prolongation of cQT; baseline QTc was 394 msec, and cQT was 633 msec after vorinostat infusion and 389 msec at 24 hours. None of the patients, including the one with the grade 3 event, had a prior history of arrhythmias, cardiac disease, and none were taking concomitant medications that might prolong the QT.

Several other grade 3 serious adverse events occurred after cycle 1, and thus did not contribute to defining DLTs. These included pneumonia (n=3), varicella zoster (n=2), dyspnea (n=3), hyponatremia (n=4), fatigue (n=5), and diarrhea (n=2) (Table 2). The two patients who developed zoster were not compliant with their prescribed acyclovir prophylaxis. Several metablic abnormalities were noted, including hypokalemia, hyponatremia and hypocalcemia. Hypotension was noted in 5 patients, only one of whom required 24-hour hospital admission for hydration. Atrial fibrillation, occurred in the setting of pneumonia in one patient, with conversion to normal sinus rhythm with beta-blockers.

Table 2.

Bortezomib and vorinostat CTC-version 3 toxicities for cycles 1 and cumulative for cycles 2–8.

| Toxicity | Cycle 1 | Cycle 2–8 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Grade | No | Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Anemia | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | - | 16 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 2 | - | 2 | - | 7 | 1 | 3 | 3 | - |

| Platelets | 12 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Diarrhea | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2 | - | 11 | 8 | 1 | 2 | - |

| Nausea | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 | - | 12 | 6 | 6 | - | - |

| Vomiting | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Constipation | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | - | - | - |

| Fatigue | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | - | 11 | 2 | 4 | 5 | - |

| Fever | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | 4 | 3 | 1 | - | - |

| Peripheral neuropathy |

13 | 11 | 2 | - | - | 14 | 5 | 9 | 1 | - |

| Dyspnea | 0 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - |

| Hypotension | 0 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Atrial fib. | 0 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Prolonged QTC | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | - | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Pneumonia | 0 | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | 3 | - |

| Shingles | 0 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | - |

| Creatinine | 7 | 2 | 5 | - | - | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | - |

| Hyponatremia | 6 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 10 | 6 | - | 4 | - |

| Hypokalemia | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | 5 | 3 | - | 2 | - |

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| LDH | 5 | 3 | 2 | - | - | 4 | 4 | - | - | - |

| AST | 4 | 3 | 1 | - | - | 5 | 4 | - | 1 | - |

| ALT | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | - |

Eleven patients (48%) had adverse events that required dose modification. These included 8 patients in whom bortezomib was decreased from 1.3 mg/m2 to 1 mg/m2 for grade 3 peripheral neuropathy (n=4) or grade 3 thrombocytopenia (n=4), and an additional 3 patients who required a decrease in vorinostat dose for grade 3 diarrhea. After dose modification, discontinuation or interruption, all patients recovered from these events within 2 weeks. One of the 8 patients treated at the MTD stopped vorinostat after 2 doses in cycle 1 due to mild nausea and during cycle 2 due to diarrhea, but then continued therapy for 3 subsequent cycles at a vorinostat dose of 200 mg/day.

Responses

Table 3 summarizes responses. Overall, 9 of 21 (42%) evaluable patients achieved objective responses, including 2 VGPR and 7 PR. Three of the 9 responses occurred in bortezomib-refractory patients. Although the numbers were small, more responses occurred at the MTD (vorinostat 400 mg daily), with 6 of 11 patients achieving a PR or better (55%) compared to lower vorinostat doses, at which 3 of 12 patients achieved responses (25%). Dexamethasone was added for patients with less than a partial response after cycle 2 (n=6) or cycle 4 (n=5) and in cycle 6 for 2 patients with progressive disease. There was no improvement in response with the addition of dexamethasone to the regimen in any patient. This lack of response to dexamethasone in these heavily pretreated patients, despite prior response, does not mean that the addition of dexamethasone to the combination of bortezomib and vorinostat would not be beneficial in less heavily pretreated patients.

Table 3.

Overall response to vorinostat and bortezomib

| Response | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Bortezomib | No of Pts N=23 |

VGPR | PR | SD | PD | NE |

| Naïve | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Pre-treatment | 10 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Refractory | 9 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pts treated at MTD, N=11 | ||||||

| Naïve | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Pre-treatment | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Refractory | 6 | 2 | 4 | |||

VGPR, very good partial response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NE, not evaluable.

Three patients completed the 8 cycles on the study and remained in remission for 9, 6 and 6 months. Six patients discontinued therapy due to toxicity, including 2 patients during cycle 1 due to DLT, 2 patients, both in PR, after cycle 4 due to worsening peripheral neuropathy and 2 patients, both with SD, in cycles 3 and 5 due to fatigue. Fourteen patients went of study due to PD. At last follow-up, 15 patients had PD. The median time to progression from study entry was 4 months; the corresponding 95% confidence interval lower limit was 3.12 months, and the upper limit has not been reached yet. Twelve patients had died, among them 3 from aggressive transformation to plasma cell leukemia.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic data from patients treated with 100, 200, 400, and 500 mg of vorinostat are presented in Table 4. Vorinostat Cmax increased with doses between 100 and 400 mg, but was not statistically different between 400 and 500 mg (p=0.35). Vorinostat tmax varied between 0.5 and 6 hours, and vorinostat t1/2 varied between 0.8 and 7.6 hours. While vorinostat AUC increased with dose, the increase was greater than proportional, and vorinostat CL/F decreased with increasing dose [the slope of Cl/F (L/min) versus dose (mg) was −0.014; p=0.001].

Table 4.

Vorinostat Pharmacokinetics

| Dose | Cmax | tmax | t1/2 | AUCINF | CL/F | CL/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mM) | (h) | (h) | (mM*h) | (l/h) | (l/min) | |

| 100 mg BID (n=6) | ||||||

| Mean | 0.31 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.76 | 605 | 10.1 |

| SD | 0.14 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.43 | 246 | 4.1 |

| 200 mg BID (n=3) | ||||||

| Mean | 0.65 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 2.03 | 383 | 6.4 |

| SD | 0.35 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.40 | 82 | 1.4 |

| 400 mg daily (n=10) | ||||||

| Mean | 1.42 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 5.13 | 313 | 5.2 |

| SD | 0.32 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.22 | 87 | 1.4 |

| 500 mg daily (n=3) | ||||||

| Mean | 1.33 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 8.10 | 246 | 4.1 |

| SD | 0.15 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.17 | 73 | 1.2 |

Pharmacodynamic studies

Baseline marrow samples were collected from 12 patients, median total cell count was 19.9×106 (range: 3.6–157×106) with a median CD138+ cell of 3.05 ×106 (range: 0.36–97 ×106). Three patients refused day 11 bone marrow aspiration, for the rest, total cell count was 15.1 ×106 (range: 4.1–31 ×106) with a median CD138+ fraction of 4.2 ×106 (range: 1.7–7.5 ×106). Protein extraction at baseline and day 11 samples yielded adequate amounts for analysis in 8 patients.

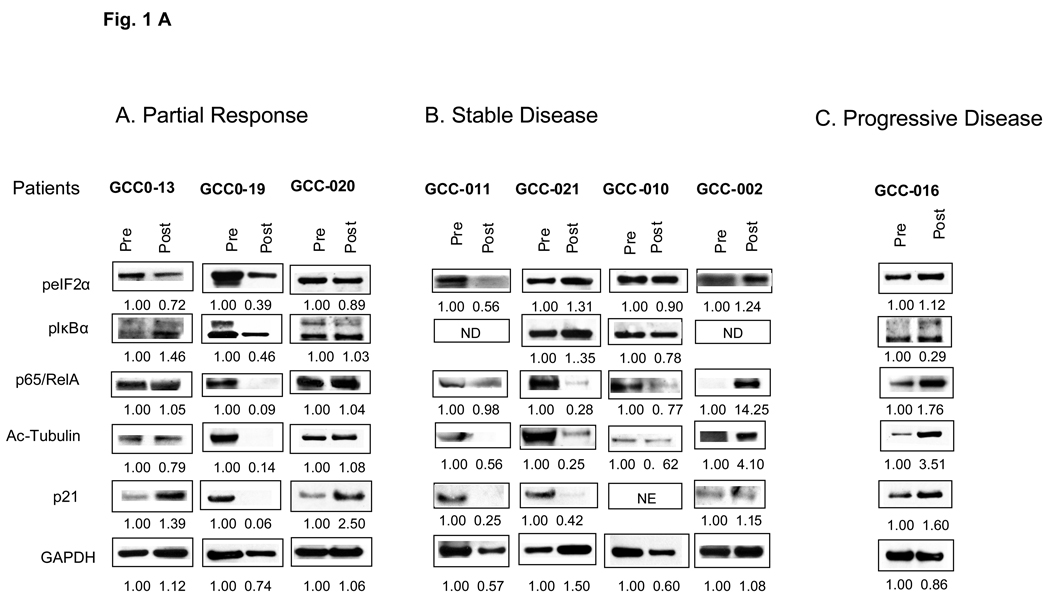

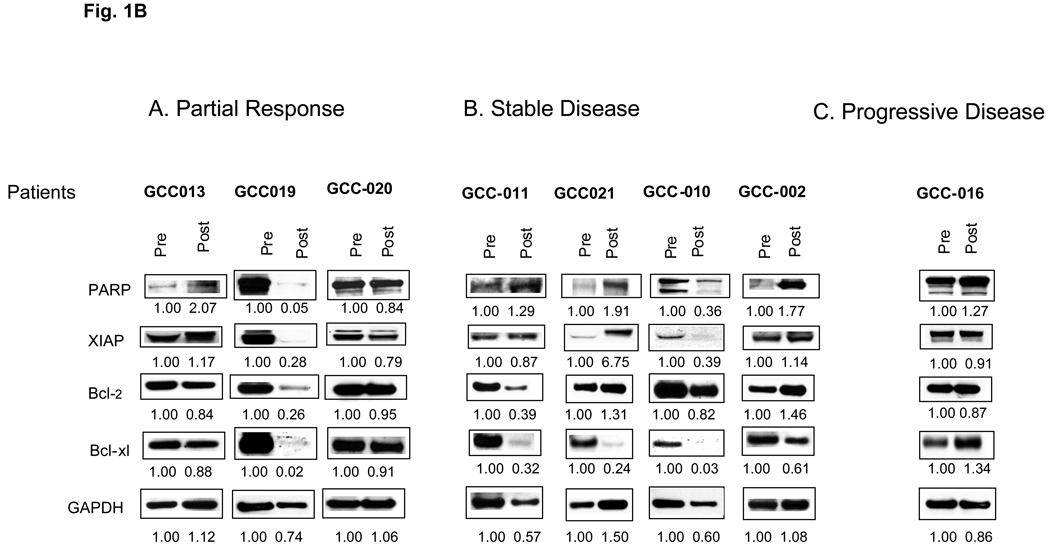

Overall expression for various proteins did not correlate with response. For example, cells from the patient GCC-016, progressive disease, displayed increased expression of p21CIP1, acetylated tubulin and total p65/RelA, and a slight increase in Bcl-xL post-treatment (Figures 1 A and B). Disparate responses were observed in cells obtained from two responding patients. Patient GCC-19 displayed a marked reduction in the expression of PARP, phospho-eIF2α, acetylated tubulin, p21CIP1, Bcl-2, XIAP, Bcl-xL, p65/RelA, and phospho-IκBα. While patient GCC-20 displayed an increase in PARP and p21CIP1 and a modest decrease in phospho-eIF2α. Cells from patients with SD displayed heterogeneous responses, with increases in certain proteins (e.g., p21CIP1 and p65/RelA). The only discernible trend was a post-treatment decrease in Bcl-xL in patients with SD and PR.

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of biomarkers corresponding to HDAC inhibitor-related proteins (Figure 1, A) and apoptosis-related proteins (Figure 1, B) from CD138+ myeloma cells. Panels A, B, and C display results for baseline and day 11 bone marrow samples following vorinostat-bortezomib therapy in relationship to clinical responses. Numbers reflect densitometric scans of each protein normalized to pre-treatment values, arbitrarily designated as 1.00.

DISCUSSION

This is the first clinical trial describing the safety and response profile of a regimen combining an HDAC inhibitor, vorinostat, with a proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, in heavily pretreated relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma patients. The MTD of oral vorinostat was determined to be 400 mg once daily for 8 days (days 4–11) with bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 administered on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 of a 21-day cycle. A twice-daily dosing regimen was employed initially to prolong the duration of HDAC inhibitor activity,. Subsequently, a daily dosing schedule was used to achieve higher peak HDAC inhibitor concentrations following bortezomib administration to enhance potential synergism between the drugs. There were no apparent differences in responses or toxicities between the once daily and twice daily regimens.

The toxicity profile of vorinostat and bortezomib supports the concept that both proteasome inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors selectively target malignant cells, rather than normal cells.(28, 29) The most common toxicities were hematological, gastrointestinal and fatigue. The events were mild-to-moderate in severity and were similar to those observed in previous trials with vorinostat. (19, 30–32) Patients rapidly recovered from the majority of these events, within 2–3 weeks of dose modification, interruption or discontinuation of the drug.

Prolonged QTc was noted in a number of our patients, but was not clinically significant. In the single patient with grade 3 QTc prolongation, the event was asymptomatic, with reversal seen in follow-up electrocardiograms. QT interval prolongation is a recently recognized side effect of molecularly targeted drugs.(33) At least four HDAC inhibitors examined to date—including vorinostat(34), panobinostat(35), depsipeptide (36)(37), and LAQ82411—have shown evidence of QTc prolongation in phase I and/or II studies. Although QTc prolongation is associated with a risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias such as torsade de pointes, it is important to note that the QT abnormalities observed in HDAC inhibitor clinical trials have not been associated with any symptomatic or clinically significant events. The actual incidence and, more importantly, the significance of QTc prolongation has not been clearly defined for any HDAC inhibitor including vorinostat.(38) Until a definitive study and more data are available, it seems reasonable to obtain baseline and periodic electrocardiograms as a precaution during treatment with vorinostat. Moreover, this combination should be used with particular care in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or those taking medications that may lead to QT prolongation. Additionally, potassium and magnesium levels should be monitored, and hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia should be corrected prior to drug administration in all patients.

Vorinostat pharmacokinetics were not altered by co-administration of bortezomib. The values for vorinostat Cmax, AUC, t1/2 and CL/F are consistent with those previously published for single-agent vorinostat, suggesting no interactions with bortezomib.(39) This was not surprising, as the two drugs have different metabolic pathways, and is consistent with the observation that bortezomib is an excellent partner in many combination therapies.

We have documented encouraging activity for the combination of vorinostat and bortezomib in relapsed, as well as refractory, multiple myeloma patients. Although limited in number, the responses occurring in bortezomib-refractory patients are clearly of interest. The precise mechanism underlying the favorable interaction between vorinostat and bortezomib is unknown. Notably, HDAC inhibitors have been shown to inhibit NF-κB, among their numerous effects, in multiple myeloma cells.(6) As NF-κB activation represents a critical factor in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma,(40) it is conceivable that in bortezomib-resistant cells, combined treatment may reduce NF-κB levels below those necessary for survival. Resolution of this issue will require a better understanding of the mechanisms by which multiple myeloma cells develop resistance to bortezomib, and determination of whether such factors are circumvented by HDAC inhibitors. Of potential relevance to this question is the recent observation that constitutively activated NF-κB in multiple myeloma cells may be intrinsically insensitive to the effects of proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, at least when they are administered ex vivo.(41) Whether a similar phenomenon occurs in cells exposed to bortezomib in vivo remains to be established.

We attempted to determine whether pharmacodynamic changes induced by HDAC and/or proteasome inhibitors in preclinical studies could be documented in post-treatment specimens. These included assessment of modulation of proteins involved in regulation of cell cycle or apoptosis (e.g., PARP cleavage, alterations in Bcl-2 or p21CIP1 expression),(16, 42) changes in expression of p65/RelA or IκBα,(43, 44), downregulation of the NF-κB-dependent proteins Bcl-xL and XIAP,(18) induction of ER stress (eIF2α phosphorylation),(45) and acetylation of tubulin,(10) by Western blotting. Preclinical evidence suggests that the basis for interactions between bortezomib and vorinostat may be multifactorial and involve, among other factors, enhanced inactivation of NF-κB, downregulation of anti-apoptotic NF-κB-dependent proteins, disruption of aggresome function, and induction of ER stress.(15, 18, 46) In our pharmacodynamic studies, which are in the context of this Phase I trial, necessarily preliminary and should be considered exploratory, there was no clear signal or association with response for the various proteins evaluated. The results of the Western blotting analyses suggest that some of the anticipated changes in multiple myeloma cell protein expression following in vivo administration of vorinostat and bortezomib occurred in a subset of patients, but with a high degree of variability. In view of multiple factors, including the small sample size, the limited number of specimens for analysis and differences in drug doses, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding pharmacodynamic findings and their lack of correlation with response. It should also be noted that acetylation of histones H3 and H4 was not monitored in this trial, in part because the results of some preclinical studies suggest that this process does not correlate closely with HDAC inhibitor-mediated lethality.(47) It is possible that NF-κB activation status as determined by EMSA analysis, rather than expression of p65/RelA or IκBα, may correlate more closely with responses to a regimen combining bortezomib and a HDAC inhibitor. However, limited sample availability precluded such assays. Furthermore, dynamic considerations could influence the abundance of proteins such as IκBα. For example, while proteasome inhibition would be expected to promote IκBα accumulation, inhibition of NF-κB may limit its synthesis.(48) Of the multiple laboratory correlates examined, downregulation of Bcl-xL appeared to correlate best with lack of disease progression. Finally, a recent study has shown that Myc regulates the sensitivity of MM cells to bortezomib and vorinostat in vitro and that its expression directly correlates with the percentage of aggresome-positive cells and cell death.(49) Whether the expression of Myc or other proteins will correlate with responsiveness to vorinostat/bortezomib therapy will best be addressed in successor phase II trials that utilize uniform drug dosing and involve a significantly larger number of patients.

In summary, results of this Phase I trial indicate that vorinostat can be administered at a dose of 400 mg daily for 8 days in conjunction with bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 to patients with relapsed multiple myeloma, with manageable toxicity. Encouraging activity was observed in this trial, with responses in patients who were previously proven bortezomib-unresponsive. Based upon these results, further evaluation of vorinostat and bortezomib in patients with relapsed and relapsed/refractory myeloma is warranted. Multi-center phase II and III trials have been initiated.

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE

This is a report of a phase I clinical trial of a novel combination of bortezomib and vorinostat in relapsed/refractory myeloma patients. The trial was based on extensive pre-clinical work demonstrating in vitro synergistic activity for the combination. We defined the maximum tolerated dose and the pharmacokinetics of vorinostat when administered in combination with bortezomib. Pharmacodynamic changes in protein levels of NF-κB, IκB, acetylated tubulin and p21CIP1 in plasma cells isolated from the bone marrow on days 1 (pre-treatment) and 11 of vorinostat and bortezomib in the study did not correlate with the patients’ clinical responses. The regimen was well tolerated and had promising anti-myeloma activity. This work is the basis of an upcoming Phase II and III clinical trials to confirm the overall response in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported in part by NIH grant # MO1-RR00071 and NCI contract N01-CO-124001 (AB), subcontract 25XS115-Task Order 2 (ME) and supported in part by CA93783 and CA 100866 (SG). We thank Colette Burgess and Daniela Buac for excellent technical support with isolation of bone marrow myeloma cells. The authors gratefully acknowledge the work performed by research teams at all participating study sites; and a special thank you to all of our patients and their families for their participation.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

AB: designed the study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

AMB: processed BM.

SP and CH: followed the study patients.

RN: contributed patients to the study.

JLH and MJE: performed the pharmacokinetic analyses and wrote the PK section.

OG and MRB: analyzed the data and helped write the paper

JZ, JJW and IED: provided guidance into the study design and reviewed the data.

SSK and SG: performed the pharmacodynamic analyses and wrote the PD section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar SK, Therneau TM, Gertz MA, et al. Clinical course of patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(7):867–874. doi: 10.4065/79.7.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2609–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Blood. 2003;101(4):1530–1534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441(7092):431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, et al. Transcriptional signature of histone deacetylase inhibition in multiple myeloma: biological and clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(2):540–545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazlehurst LA, Damiano JS, Buyuksal I, Pledger WJ, Dalton WS. Adhesion to fibronectin via beta1 integrins regulates p27kip1 levels and contributes to cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) Oncogene. 2000;19(38):4319–4327. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landowski TH, Olashaw NE, Agrawal D, Dalton WS. Cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) is associated with activation of NF-kappa B (RelB/p50) in myeloma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(16):2417–2421. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Richardson P, Anderson KC. Proteasome inhibitor therapy in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(4):686–692. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hideshima T, Bradner JE, Wong J, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of proteasome and aggresome function induces synergistic antitumor activity in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(24):8567–8572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503221102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1(3):194–202. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Richardson PG, et al. Molecular sequelae of histone deacetylase inhibition in human malignant B cells. Blood. 2003;101(10):4055–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A, Yao TP. The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell. 2003;115(6):727–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bali P, Pranpat M, Bradner J, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26729–26734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Pino MS, et al. Aggresome disruption: a novel strategy to enhance bortezomib-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3773–3781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catley L, Weisberg E, Tai YT, et al. NVP-LAQ824 is a potent novel histone deacetylase inhibitor with significant activity against multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102(7):2615–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Y, Rahmani M, Dent P, Grant S. Blockade of histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced RelA/p65 acetylation and NF-kappaB activation potentiates apoptosis in leukemia cells through a process mediated by oxidative damage, XIAP downregulation, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(13):5429–5444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5429-5444.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai Y, Chen S, Pei XY, et al. Interruption of the Ras/MEK/ERK signaling cascade enhances Chk1 inhibitor-induced-DNA damage in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson P, Mitsiades C, Colson K, et al. Phase I trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(3):502–507. doi: 10.1080/10428190701817258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang CY, Kim IY, Kwon KS. Cytoplasmic localization and ubiquitination of p21(Cip1) by reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(1):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng J, Lu PD, Zhang Y, et al. Translational repression mediates activation of nuclear factor kappa B by phosphorylated translation initiation factor 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(23):10161–10168. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10161-10168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20(9):1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parise RA, Holleran JL, Beumer JH, Ramalingam S, Egorin MJ. A liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric assay for quantitation of the histone deacetylase inhibitor, vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamicacid, SAHA), and its metabolites in human serum. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;840(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeh KC, Kwan KC. A comparison of numerical integrating algorithms by trapezoidal, Lagrange, and spline approximation. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6(1):79–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01066064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocci ML, Jr, Jusko WJ. LAGRAN program for area and moments in pharmacokinetic analysis. Comput Programs Biomed. 1983;16(3):203–216. doi: 10.1016/0010-468x(83)90082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pei XY, Dai Y, Rahmani M, Li W, Dent P, Grant S. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor L744832 potentiates UCN-01-induced apoptosis in human multiple myeloma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(12):4589–4600. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badros AZ, Goloubeva O, Rapoport AP, et al. Phase II study of G3139, a Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, in combination with dexamethasone and thalidomide in relapsed multiple myeloma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4089–4099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An B, Goldfarb RH, Siman R, Dou QP. Novel dipeptidyl proteasome inhibitors overcome Bcl-2 protective function and selectively accumulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human fibroblasts. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5(12):1062–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ungerstedt JS, Sowa Y, Xu WS, et al. Role of thioredoxin in the response of normal and transformed cells to histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):673–678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Manero G, Yang H, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Phase 1 study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid [SAHA]) in patients with advanced leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2008;111(3):1060–1066. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crump M, Coiffier B, Jacobsen ED, et al. Phase II trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) in relapsed diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(5):964–969. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duvic M, Talpur R, Ni X, et al. Phase 2 trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) Blood. 2007;109(1):31–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-025999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strevel EL, Ing DJ, Siu LL. Molecularly targeted oncology therapeutics and prolongation of the QT interval. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3362–3371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen EA, Kim YH, Kuzel TM, et al. Phase IIb multicenter trial of vorinostat in patients with persistent, progressive, or treatment refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3109–3115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giles F, Fischer T, Cortes J, et al. A phase I study of intravenous LBH589, a novel cinnamic hydroxamic acid analogue histone deacetylase inhibitor, in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4628–4635. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah MH, Binkley P, Chan K, et al. Cardiotoxicity of histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):3997–4003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piekarz RL, Frye AR, Wright JJ, et al. Cardiac studies in patients treated with depsipeptide, FK228, in a phase II trial for T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(12):3762–3773. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Lebwohl D, Masson E, Laird G, Cooper MR, Prince HM. Clinically relevant QTc prolongation is not associated with current dose schedules of LBH589 (panobinostat) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):332–333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7249. discussion 3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramalingam SS, Parise RA, Ramanathan RK, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel for advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3605–3610. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Poulaki V, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of intracellular anti-apoptotic proteins via the IGF-1/Akt signaling in human multiple myeloma cells: therapeutic implications. Oncogene. 2002;21(37):5673–5683. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markovina S, Callander NS, O'Connor SL, et al. Bortezomib-resistant nuclear factor-kappaB activity in multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(8):1356–1364. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pei XY, Dai Y, Grant S. Synergistic induction of oxidative injury and apoptosis in human multiple myeloma cells by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(11):3839–3852. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peart MJ, Smyth GK, van Laar RK, et al. Identification and functional significance of genes regulated by structurally different histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(10):3697–3702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500369102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor S, Markovina S, Miyamoto S. Evidence for a phosphorylation-independent role for Ser 32 and 36 in proteasome inhibitor-resistant (PIR) IkappaBalpha degradation in B cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Pino MS, et al. Bortezomib sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11658–11666. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catley L, Weisberg E, Kiziltepe T, et al. Aggresome induction by proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and alpha-tubulin hyperacetylation by tubulin deacetylase (TDAC) inhibitor LBH589 are synergistic in myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;108(10):3441–3449. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosato RR, Almenara JA, Grant S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 promotes differentiation or apoptosis in human leukemia cells through a process regulated by generation of reactive oxygen species and induction of p21CIP1/WAF1 1. Cancer Res. 2003;63(13):3637–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karin M, Yamamoto Y, Wang QM. The IKK NF-kappa B system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(1):17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Maclean KH, et al. Myc regulates aggresome formation, the induction of Noxa, and apoptosis in response to the combination of bortezomib and SAHA. Blood. 2008;112(7):2917–2926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]