Abstract

Iodotyrosine deiodinase is essential for iodide homeostasis and proper thyroid function in mammals. This enzyme promotes a net reductive deiodination of 3-iodotyrosine to form iodide and tyrosine. Such a reductive dehalogenation is uncommon in aerobic organisms, and its requirement for flavin mononucleotide is even more uncommon in catalysis. Reducing equivalents are now shown to transfer directly from the flavin to the halogenated substrate without involvement of other components typically included in the standard enzymatic assay. Additionally, the deiodinase has been discovered to act as a debrominase and a dechlorinase. These new activities expand the possible roles of flavin in biological catalysis and provide a foundation for determining the mechanism of this unusual process.

Halogenated compounds and solvents have great economic value but pose long term threats to the environment. Chlorinated compounds in particular resist microbial degradation and accumulate in soil and water. Only a limited number of organisms have demonstrated an ability to metabolize such compounds and hence have become central to developing biological methods of remediation.1 Anaerobes contribute significantly to this process by catalyzing reductive dehalogenation.2,3 A number of catalytic strategies utilizing a range of cofactors are associated with these processes. For example, both cobalamin and Fe/S-centers are involved in the reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethene and chlorophenol.4 Porphyrins, factor F430, ferredoxins and even flavin may also participate in various other reductive dechlorinations although no direct role for flavin has yet to be established.3,5,6

In contrast to anaerobes, aerobes rarely support reductive dehalogenation despite a few notable exceptions.7 Perhaps the best characterized exception is a bacterial dehalogenase that couples reductive dechlorination of tetrachlorohydroquinone to the oxidation of glutathione.8 Human health depends on another exception, iodothyronine deiodinase, that promotes reductive deiodination of the thyroid hormone thyroxine.9 Neither of these two exceptions require a cofactor. Instead, active site Cys and Sec (selenocysteine) residues respectively are directly responsible for substrate reduction. Yet another reductive dehalogenase, iodotyrosine deiodinase (IYD), is also critical for human health. Proper thyroid function depends on this enzyme's ability to salvage iodide from 3-iodo- and 3,5-diiodotyrosine that are generated as byproducts of thyroxine biosynthesis (eq. 1). A deficiency in this enzyme can results in a lack of adequate iodide retention and ultimately hypothyroidism.10

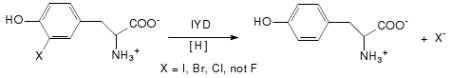

|

(1) |

IYD is the only dehalogenase known to contain flavin mononucleotide (FMN).11,12 Reaction is thought to depend on reducing equivalents from NADPH in vivo and can be reconstituted with dithionite in vitro.13 Thiols alone do not promote this reaction nor are cysteine residues within the enzyme required for activity.14,15 Flavins are known to promote a wide range of one and two electron processes including activation of molecular oxygen, reduction of disulfides and sulfenic acid, transfer of hydride and electrons, and even halogenation of natural products,16 but no mechanistic precedent exists to date for involvement of flavin in reductive dehalogenation. The standard assay used for detecting iodide release from iodotyrosine is complex and contains free flavin, dithionite, methimazole and 2-mercaptoethanol.14 As described for the first time below, the active site flavin is solely responsible for reduction and deiodonation of 3-iodotyrosine (I-Tyr). This enzyme has also been discovered to act as a general dehalogenase by promoting reductive dehalogenation of 3-bromo- and 3-chlorotyrosine (Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr, respectively). Only 3-fluorotyrosine (3-F-Tyr) remains inert to the reduced form of IYD.

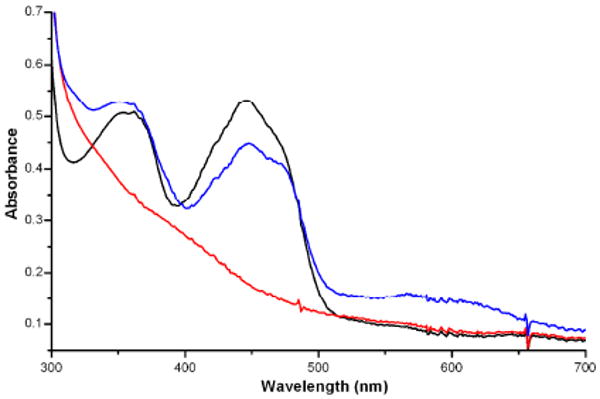

Recent success in heterologous expression of IYD provided sufficient quantities of the enzyme for detailed studies. The structure of an I-Tyr/IYD co-crystal determined at 2.45 Å resolution revealed an intimate association between the substrate and oxidized form of the active site-bound flavin.17 Despite this new wealth of structural information, the chemical requirements and scope of dehalogenation remained unknown. Accordingly, the reduced form of IYD was generated in the absence of the typical array of additives used in the standard activity assay by titration with a stoichiometric quantity of dithionite under anaerobic conditions. Reduction was monitored by the characteristic loss of absorbance by flavin in the visible spectrum (Figures 1 and S1). Subsequent addition of I-Tyr regenerated the spectrum of the oxidized flavin suggesting a direct discharge of electrons to the halogenated substrate (Figure S2). IYD was also competent to undergo additional cycles of reduction and oxidation as expected for a catalytic process. Chromatographic analysis of the titration mixture confirmed consumption of ca. 1 equiv. of I-Tyr and concomitant production of 1 equiv. of tyrosine (Tyr) per redox cycle of IYD (Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Absorbance spectra of reduced and oxidized IYD under anaerobic conditions. The oxidized flavin of IYD ( ) was fully reduced by addition of an equiv. of dithionite (

) was fully reduced by addition of an equiv. of dithionite ( ). Electrons were discharged from this reduced flavin after addition of excess I-Tyr (2 equiv.) (

). Electrons were discharged from this reduced flavin after addition of excess I-Tyr (2 equiv.) ( ).

).

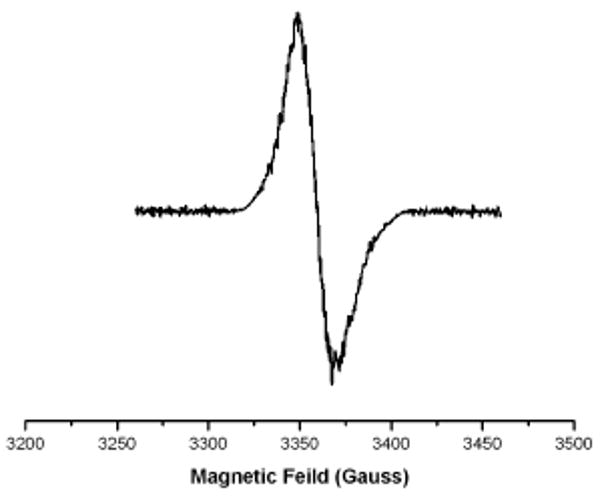

A broad absorbance band from 550 - 650 nm was additionally evident during substrate-dependent oxidation of IYD. This is attributed to a neutral flavin radical and represents ca. 33% of the flavin species based on an estimated ε585 of 4900 M-1 cm-1.12 EPR analysis confirmed the presence of this radical by its g-factor of 2.0027 and line width of 20.3 G (Figure 2).18 The radical is surprisingly stable and persists at 4 °C under aerobic conditions for many days as monitored by A585. However, quantitation of the EPR signal suggested that only 8% of the flavin species remained as a radical after 16 hr.

Figure 2.

EPR spectrum of IYD following anaerobic reduction and subsequent discharge of electrons by substrate. X-band EPR measurements were made with an IYD sample (250 μM) stored 16 hrs at 4 °C under aerobic conditions following addition of I-Tyr.

Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr are also capable of oxidizing reduced IYD under the same conditions described above for I-Tyr, and similarly, these substrates are dehalogenated to form tyrosine as well (Table 1 and Figures S3, S4 and S5). Thus, the reduced flavin bound to the active site of IYD sustains a catalytic power sufficient to promote cleavage of the carbon-bromine and carbon-chlorine bond in addition to the much weaker carbon-iodine bond. Only F-Tyr was unable to discharge electrons from the reduced flavin of IYD or undergo defluorination. This lack of reaction is not surprising due to the resilience of the carbon-fluorine bond and cannot be attributed to its affinity for IYD. Substrate and ligand binding to IYD was measured independently from enzyme turnover by monitoring fluorescence quenching of the flavin (Table 1, Figure S6). The dissociation constants for I-Tyr, Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr are almost equivalent, and their sub-μM values demonstrate a very high affinity for IYD. Even F-Tyr binds quite tightly to IYD despite the diminutive size of fluorine vs. the other halogen substituents. Still, the effect of all halogens is significant when comparing binding of the halotyrosines to that of Tyr or 3-methyltyrosine (KD > 150 μM, Figure S6). This trend is likely influenced by the pKa of the phenolic proton (Table 1), but certainly sterics and perhaps non-covalent halogen bonding19 also contribute.

Table 1.

Recognition and Processing of Halotyrosines by IYD.

Flavin may now be added to the pantheon of cofactors that are competent to promote reductive dehalogenation. Consequently, the flavoprotein IYD offers a fresh target to engineer for bioremediation. The significance of the debromination and dechlorination reactions catalyzed by IYD, however, is most immediate for human health and metabolism. Only one report had previously suggested the debromination reaction, and this relied on the release of [82Br]-bromide from [82Br]-Tyr in the presence of thyroid microsomes.20 More recently, Cl-Tyr was thought not to act as a substrate for IYD,21 although this observation may have resulted from an instability of the endogenous reductase required for NADPH dependent deiodination. Both Cl-Tyr and Br-Tyr are indirectly generated by peroxidases in our body and have been used as markers for lung disease and asthma.21,22 Although IYD in the thyroid is unlikely to contribute to their metabolism, its reported presence in the liver and the kidney would provide a likely site for dehalogenation.21,23 The ability of IYD to promote aromatic debromination and dechlorination expands its potential role in mammalian biology and provides a foundation for future mechanistic studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Veronika Szalai for performing the EPR spectroscopy and Min Jia for help with the initial anaerobic titrations. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (DK 084186 to SR) and the Herman Kraybill Biochemistry Fellowship (PM).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: General materials and methods, complete reduction and oxidation titrations of IYD, HPLC analysis of halotyrosine dehalogenation, binding titrations of halotyrosines with IYD. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Häggblom MM, Bossert ID. Dehalogenation: microbial processes and environmental applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2003. p. 520. [Google Scholar]; (b) Parales RE, Haddock JD. Curr Opin Biotech. 2004;15:374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wackett LP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41259–41262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovely DR. Science. 2001;293:1444–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.1063294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holliger C, Regeard C, Diekert G. Dehalogenation by anaerobic bacteria. In: Häggblom MM, Bossert ID, editors. Dehalogenation: microbial processes and environmental applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2003. pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Neumann A, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16515–16519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) van de Pas BA, Smidt H, Hagen WR, van der Oost J, Schraa G, Stams AJM, de Vos WM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20287–20292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.French AL, Hoopingarner RA. J Econ Entomol. 1970;63:756–759. doi: 10.1093/jee/63.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki T, Kasia N. Trends Glycosci Glycotechn. 2003;15:329–349. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Fetzner S. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:633–657. doi: 10.1007/s002530051346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Copley SD. Microbial dehalogenases. In: Poulter CD, editor. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry. Vol. 5. Elsevier Science Ltd; Oxford: 1999. pp. 401–422. [Google Scholar]; (c) de Jong RM, Dijkstra BW. Curr Opin in Struct Biol. 2003;13:722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Copley SD. Aromatic dehalogenases: insights into structures, mechanisms, and evolutionary origins. In: Häggblom MM, Bossert ID, editors. Dehalogenation: microbial processes and environmental applications. Kluwer Academic Publishes; Boston: 2003. pp. 227–259. [Google Scholar]; (b) Warner JR, Copley SD. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13211–13222. doi: 10.1021/bi701069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Endocrine Rev. 2002;23:38–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Valverde-R C, Orozco A, Becerra A, Jeziorski MC, Villalobos P, Solis-S JC. Int Rev of Cytology. 2004;234:143–199. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)34004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno JC, Klootwijk W, van Toor H, Pinto G, D'Alessandro M, Lèger A, Goudie D, Polak M, Grüters A, Visser TJ. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1811–1818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg IN, Goswami A. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:12318–12325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goswami A, Rosenberg IN. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:12326–12330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goswami A, Rosenberg IN. Endocrinology. 1977;101:331–341. doi: 10.1210/endo-101-2-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg IN, Goswami A. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:488–500. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson JA, McTamney PM, Adler JM, Rokita SE. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:504–506. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) De Colibus L, Mattevi A. Curr Opin in Struct Biol. 2006;16:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Joosten V, van Berkel WJH. Curr Opin in Chem Biol. 2007;11:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mansoorabadi SO, Thibodeaux CJ, Liu Hw. J Org Chem. 2007;72:6329–6342. doi: 10.1021/jo0703092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) van Pée KH, Patallo EP. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:631–641. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas S, McTamney PM, Adler JM, LaRonde-LeBlanc N, Rokita SE. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19659–19667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer G, Muller F, Massey V. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies on flavoprotein radicals. In: Karmin H, editor. Flavins and Flavoproteins, 3rd International Symposium; Baltimore: University Park Press; 1971. pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Auffinger P, Hays FA, Westhof E, Ho SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16789–16794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407607101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Metrangolo P, Meyer F, Pilati T, Resnati G, Terraneo G. Ang Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6114–6127. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Matter H, Nazaré M, Güssregen S, Will DW, Schreuder H, Bauer A, Urmann M, Ritter K, Wagner M, Wehner V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2911–2916. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche J, Michel O, Michel R, Gorbman A, Lissitzky S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953;12:570–576. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mani AR, Ippolito S, Moreno JC, Visser TJ, Moore KP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29114–29121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Wu W, Samoszuk MK, C SA, Thomassen MJ, Farver CF, Dweik RA, Kavuru MS, Erzurum SC, Hazen SL. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1455–1463. doi: 10.1172/JCI9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Buss IH, Senthilmohan R, Darlow BA, Mogridge N, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:455–462. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000050655.25689.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Stanbury JB, Morris ML. J Biol Chem. 1958;233:106–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moreno JC. Horm Res. 2003;3:96–102. doi: 10.1159/000074509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stradins J, Hansanli B. J Electroanal Chem. 1993;353:57–69. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.