Abstract

The suppression of hepatitis B viral (HBV) load correlates with favorable histologic, biochemical, and serologic responses in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). The ability to identify patients who will not experience durable viral suppression in response to a specific antiviral regimen affords the opportunity for early treatment modification to optimize outcomes and avoid the development of antiviral resistance. Substantial evidence demonstrates that on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels are predictive of virologic response and risk of resistance. Regional clinical practice guidelines for the management of CHB universally recommend monitoring serum HBV DNA levels at treatment week 24. However, the value of this time point as a predictor of long-term success may not be applicable to all types of antiviral therapy. Indeed, each oral nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) antiviral therapy has a unique profile of potency, genetic barriers to resistance, and viral kinetics that may affect the optimal time point for on-treatment monitoring. This review discusses available data for appropriate predictors for long-term response and antiviral resistance for patients receiving specific oral NA antiviral therapy. Guidelines for on-treatment monitoring are also discussed.

Keywords: Antiviral therapy, Chronic hepatitis B, Treatment monitoring

Introduction

Over the past decade, an increased understanding of the cellular and molecular pathophysiology, natural history, and the risk of developing antiviral resistance to oral nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) antiviral therapy has led to efforts to optimize treatment paradigms for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Profound and sustained suppression of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication to below the level of detectability is a critical factor in achieving the primary goal of treatment: the prevention of progression to cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma [1–3]. Several effective oral NA agents are now available that induce profound suppression of serum HBV DNA levels. However, clinical experience has shown that long-term NA therapy is required to achieve treatment goals and is often hindered by the emergence of viral resistance [4]. The development of highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction-based assays for the quantification of serum HBV DNA has facilitated the investigation of the relationship between early virologic response to oral NA therapy and treatment outcomes. Early virologic response to oral NA therapy has been shown to correlate with favorable outcomes to therapy [5–16]. More specifically, substantial evidence has established that serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 or 48 of treatment are predictive of sustained virologic response, normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion, and the risk of developing antiviral resistance [5–16]. On the basis of these findings, the “roadmap” treatment strategy was developed, advocating the monitoring of serum HBV DNA levels at weeks 12 and 24 of treatment to identify primary nonresponse and partial virologic response, respectively, and to modify treatment accordingly [17]. More recently, this strategy has been incorporated into regional clinical treatment guideline recommendations [1–3]. Despite these recommendations, the universal applicability of week 24 as the optimal time point for evaluating treatment response to all oral NAs remains unclear, particularly for agents with low genetic barriers to resistance [18–20].

This article reviews the available clinical data regarding the on-treatment monitoring of HBV DNA levels as a predictor of sustained virologic response in patients receiving oral NA therapies, as well as the application of monitoring HBV DNA levels as a means of improving response to antiviral therapy. The impact of the use of specific NAs with differing potencies and viral kinetics on on-treatment monitoring protocols is discussed.

On-treatment HBV DNA levels as predictors of response and resistance

A better understanding of early viral kinetics during pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy and on-treatment monitoring of predictors of response have been shown to be important tools in optimizing the management of hepatitis C [21, 22]. Similarly, the identification of on-treatment predictors of response and resistance to oral NA therapy has gained considerable interest as a means of optimizing treatment regimens and therapeutic outcomes [23–25]. Substantial data regarding on-treatment predictors of response and resistance to lamivudine, adefovir, and telbivudine in patients with CHB have been reported in the literature [5–7, 10–14]. Limited data on predictors of response for entecavir and tenofovir have been published [9, 16].

Nucleoside analogs

Lamivudine

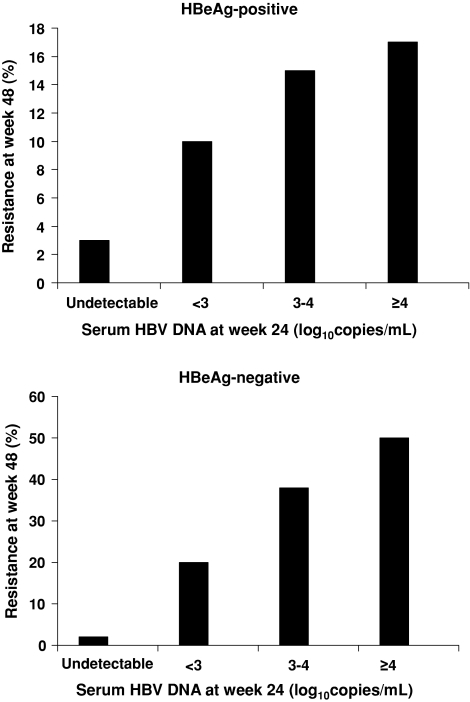

Lamivudine is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor used for the treatment of patients with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and CHB infection. Resistance to lamivudine is conferred by single-site mutation (M204V/I) in the C domain of the HBV DNA polymerase. Several studies have demonstrated that on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels are predictive of resistance to lamivudine [5, 11, 13, 26, 27]. In a 2001 study of 159 patients with HBeAg-positive CHB, who were treated with lamivudine and evaluated for a median period of 30 months, those with HBV DNA levels of more than 103 copies/ml at week 24 had a 63% chance of developing the YMDD mutation whereas those with HBV DNA levels of 103 copies/ml or less had only a 13% chance of developing the mutation [13]. Another study, involving 139 HBeAg-negative patients treated with lamivudine for 2 years, demonstrated that serum HBV DNA levels at treatment week 24 were predictive of the likelihood for resistance to lamivudine at 2 years [26]. A correlation was observed between the 2-year lamivudine resistance rates and serum HBV DNA levels at week 24. The 2-year resistance rates were 1%, 46%, and 67% in patients with week 24 HBV DNA levels of less than 102 copies/ml, 102–103copies/ml, and more than 104 copies/ml, respectively. Similar findings were reported in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial comparing telbivudine monotherapy, telbivudine plus lamivudine, and lamivudine monotherapy in HBeAg-positive patients [28]. Data from the pooled analysis of the telbivudine- and lamivudine-treated patients showed that undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at treatment week 24 were associated with a lower rate of virologic breakthrough than serum HBV DNA levels of more than 3–4 log10 copies/ml at week 24 (P < 0.05). These findings were subsequently confirmed in the randomized phase III GLOBE trial comparing telbivudine and lamivudine in 1,367 HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients with CHB [5, 6]. Resistance rates at 1 year of lamivudine treatment were lowest among those patients who had undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 of treatment (Fig. 1) [5]. More recently, Thompson et al. [27] prospectively studied 85 patients with CHB who were treated with lamivudine and reported resistance rates of 6%, 31%, and 51% at 12, 24, and 48 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified the precore variant, high baseline ALT levels, and persistent viremia at 24 weeks as independent predictors of early lamivudine resistance, with rate ratios of 4.93 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.32–18.5), 1.22 (95% CI = 1.08–1.49), and 4.73 (95% CI = 1.49–15.00), respectively (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

The effect of early viral suppression on resistance to lamivudine at 1 year in patients with hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Reprinted with permission from Lai et al. [5]

On-treatment serum HBV DNA levels have also been shown to be predictive of long-term virologic outcomes with lamivudine [11, 12, 14, 28, 29]. Early studies of lamivudine found that only patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA levels by week 24 of treatment achieved loss of HBeAg and HBeAg seroconversion [11, 12]. Pooled analyses of data from a phase II study comparing lamivudine and telbivudine showed that undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 of treatment were associated with high rates of undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (100%), ALT normalization (90%), and HBeAg loss (43%) at week 52 compared with rates of 7%, 55%, and 7%, respectively, in patients with week 24 HBV DNA levels of more than 104 copies/ml [28].

Hadziyannis et al. [14] investigated the predictive value of on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels in a study involving 156 HBeAg-negative patients who received prolonged lamivudine treatment. In this analysis, undetectable HBV DNA levels at 12 and 24 weeks of lamivudine treatment had a 93% and 72% predictive value for maintained response at 2 and more than 4 years, respectively. On-treatment serum HBV DNA levels as early as week 4 of lamivudine treatment were predictive of long-term outcomes at 5 years in patients with HBeAg-positive CHB [29]. In this study, serum HBV DNA levels were assessed at baseline, weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32, and at yearly intervals until year 5 in 74 HBeAg-positive patients with chronic HBV infection. All the patients with serum HBV DNA levels of less than 2,000 IU/ml at week 4 of lamivudine treatment had an ideal response at 5 years, including HBeAg seroconversion, ALT normalization, and serum HBV DNA levels of less than 400 IU/ml and no lamivudine resistance mutations. In contrast, 83.8% of patients who had serum HBV DNA levels of more than 2,000 IU/ml by treatment week 4 did not achieve long-term ideal response [29]. Although serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 were also predictive of outcomes at 5 years, the emergence of mutations conferring resistance to lamivudine and adefovir was detected by week 24.

Entecavir

Entecavir is a nucleoside analog that demonstrates potent antiviral activity and low rate (1.2–1.7%) of resistance in nucleoside-naive patients at 6 years of treatment [30–33]. In contrast to lamivudine, multiple mutations in the HBV polymerase gene are required to confer resistance to entecavir, contributing to the high genetic barrier of this agent [32]. Continuous treatment with entecavir for up to 6 years is associated with an increasing proportion of patients achieving undetectable serum HBV DNA levels and/or HBeAg seroconversion without a concomitant increase in resistance rate [30, 34, 35]. Thus, limited data are available regarding the predictive value of week 24 serum HBV DNA levels on resistance and virologic response because of the low probability of developing resistance at this time point. The relationship between week 24 serum HBV DNA levels and therapeutic response at week 48 in entecavir-treated patients with CHB has been reported recently [9, 36]. Ma et al. [36] investigated the predictive value of week 24 serum HBV DNA levels on week 48 virologic response in 33 lamivudine-refractory patients treated with entecavir 1.0 mg/day for 48 weeks. Patients who had undetectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 were more likely to have undetectable HBV DNA levels, ALT normalization, and lower rates of viral breakthrough at week 48. In a retrospective analysis involving 109 treatment-naive patients treated with entecavir 0.5 mg/day, ALT levels at baseline and undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 of treatment were found to be predictive of undetectable HBV DNA levels and ALT normalization at week 48 [9]. In a large, randomized, double-blind, multinational, phase III trial designed to characterize the efficacy of entecavir in HBeAg-positive patients, week 24 serum HBV DNA levels were associated with outcomes at 52 weeks of treatment [8]. Specifically, a higher proportion of patients with HBV DNA levels of less than 103 copies/ml, compared with patients whose HBV DNA levels were more than 300 copies/ml at 24 weeks of entecavir treatment, had undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (96% vs. 50%) and underwent HBeAg seroconversion (30% vs. 17%) at week 52 [8].

Telbivudine

Telbivudine is an l-nucleoside with potent and specific anti-HBV activity that demonstrates an intermediate resistance profile compared with other oral NAs. As with lamivudine, resistance is conferred by a single-site substitution (M204I) in the HBV DNA polymerase gene. In a phase III lamivudine-controlled registration trial of telbivudine in patients with CHB, resistance rates of 5.0% and 2.2% have been reported in intent-to-treat HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative individuals, respectively, after 1 year of telbivudine therapy [5]. At 2 years, resistance rates of 25.8% and 10.8% have been reported with telbivudine in HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients [6]. However, the resistance potential is mitigated in patients who achieve undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 of treatment. Lower rates of resistance at 1 year (1% HBeAg positive and 0% HBeAg negative) and 2 years (4% HBeAg positive and 2% HBeAg negative) of telbivudine therapy were observed among patients who achieved undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at treatment week 24 [5, 6].

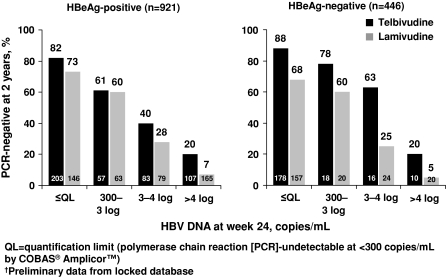

The utility of on-treatment monitoring in patients undergoing treatment with telbivudine has been well characterized in the GLOBE study, a 2-year, multinational, randomized, phase III trial that compared telbivudine 600 mg/day with lamivudine 100 mg/day in 1,367 patients with CHB. In this study, HBV DNA levels at week 24 were the best predictor of clinical and virologic efficacy responses at week 52, irrespective of HBeAg serostatus [5]. HBeAg-positive patients with undetectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 had higher rates of undetectable HBV DNA levels (90% vs. 54%) and HBeAg seroconversion (41% vs. 4%) at week 52 than patients with week 24 serum HBV DNA levels of more than 104 copies/ml. Similarly, HBeAg-negative patients with undetectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 had higher rates of undetectable HBV DNA levels (83% vs. 36%) at week 52 than those with week 24 serum HBV DNA levels of more than 104 copies/ml. Two-year data from this trial showed a similar relationship between viral suppression at week 24 and virologic outcomes at week 104 (Fig. 2), [6]. A separate multivariate analysis of pretreatment and early on-treatment factors identified undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at treatment week 24 as the strongest predictor for optimal outcomes at 2 years in telbivudine-treated patients [7].

Fig. 2.

HBV DNA suppression at 2 years compared with antiviral effect at week 24 in patients receiving telbivudine or lamivudine. Reprinted with permission from Liaw et al. [6]

More recently, undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 were shown to be predictive of optimal outcomes in patients treated with telbivudine for up to 3 years [37]. Among the 293 HBeAg-positive patients who received continuous telbivudine treatment, higher rates of undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (87% vs. 59%), ALT normalization (86% vs. 79%), and cumulative seroconversion (65% vs. 40%) were achieved at 3 years in patients who had undetectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 than in the overall patient population. Similarly, higher rates of undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (87% vs. 71%) and ALT normalization (86% vs. 77%) were observed at 3 years in HBeAg-negative patients who had undetectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 than in the overall patient population.

Nucleotide analogs

Adefovir dipivoxil

Adefovir dipivoxil is an oral nucleotide analog that demonstrates durable suppression of HBV replication, particularly in the setting of lamivudine-resistant CHB. Although adefovir effectively suppresses HBV replication, it has a slower suppressive effect on HBV replication and has been shown to be less potent than other oral NAs in randomized clinical trials [38–40]. Locarnini et al. [41] investigated the rate of adefovir resistance and factors associated with adefovir resistance in a pooled analysis of more than 1,000 patients who received adefovir treatment with or without lamivudine for 48–192 weeks. Resistance rates of 4%, 26%, and 67% were observed in patients who had serum HBV DNA levels of more than 103 copies/ml, 103–106 copies/ml, and more than 106 copies/ml, respectively, at week 48 of adefovir treatment. Logistic regression analysis of baseline HBV DNA and ALT levels, race, age, gender, body mass index, liver histology, prior HBV therapy, and treatment week 4, 12, and 48 serum HBV DNA levels identified only serum HBV DNA level at week 48 as a predictor of adefovir resistance. Hadziyannis et al. [42] investigated the efficacy, safety, and resistance profile of adefovir dipivoxil treatment for up to 240 weeks in 125 patients with CHB. In a stepwise logistic regression analysis that included demographics, genotype, and baseline fibrosis, only detectable serum HBV DNA level at week 48 was a significant predictor of resistance over 192 weeks (P = 0.0003). Seventeen (49%) out of the 35 patients with serum HBV DNA levels of 3 log copies/ml or more after 48 weeks of adefovir therapy developed adefovir resistance at 192 weeks of treatment compared with only 5 (6%) out of the 89 patients with serum HBV DNA levels of less than 3 log copies/ml at 48 weeks [42].

More recently, several studies have shown that serum HBV DNA levels at 24 weeks of adefovir are predictive of favorable outcomes in patients with CHB receiving adefovir [10, 15, 40]. In an adefovir-controlled, randomized, open-label trial of telbivudine involving 135 treatment-naive, HBeAg-positive adults with CHB, undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 were associated with high rates of virologic response at week 52 [40]. Specifically, a higher proportion of patients with undetectable HBV DNA levels at 24 weeks had undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (90% vs. 25%), ALT normalization (90% vs. 83%), and HBeAg seroconversion (50% vs. 9%) at week 52 than the proportion of patients who had detectable HBV DNA levels at week 24 of adefovir treatment. In addition, Pritchett et al. [15] reported that lamivudine-resistant patients who had a more than 50% reduction in serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 of adefovir treatment were more likely to have undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at 1 year. In a single-center cohort study involving 76 patients with CHB treated with long-term adefovir monotherapy, serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 demonstrated a higher predictive value for virologic response at week 122 than serum HBV DNA levels at week 48 [10]. Of note, patients without undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at week 24 demonstrated a trend toward the emergence of adefovir resistance (P = 0.07). The findings from these studies appear to indicate that virologic response to adefovir therapy can be assessed at 24 weeks instead of the generally recommended 48 weeks.

Tenofovir

Tenofovir, an acyclic NA with a molecular structure similar to that of adefovir, is approved for the treatment of patients with HIV infection and CHB. No resistance to tenofovir has been reported in patients with HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative CHB at 1 and 2 years of treatment [38, 43–45]. Consequently, no predictors of tenofovir resistance have been identified to date. However, the value of on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels in predicting virologic response to tenofovir has been reported [43, 44]. In the adefovir-controlled phase III trial of tenofovir in treatment-naive HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, the majority of tenofovir-treated patients with an incomplete response (HBV DNA levels >400 copies/ml) at week 24 subsequently had a complete response at weeks 48 and 72, suggesting that week 24 response is not a robust predictor of virologic response to tenofovir [43, 44].

On-treatment HBV DNA monitoring strategies

Clinical experience to date confirms that on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels are an important tool for predicting the risk of developing resistance and therapeutic outcomes in patients with CHB. Several strategies for the on-treatment monitoring of oral NA therapy have emerged in an effort to reduce the emergence of antiviral resistance and improve therapeutic outcomes. Some groups have proposed practical recommendations based on experimental data. For example, in the pooled analysis of predictors of response to lamivudine therapy discussed above, Yuen et al. [29] noted that HBV DNA levels at 4 and 16 weeks were the best indictors of ideal response at 5 years. On the basis of these data, the investigators recommended a continuation of lamivudine therapy in patients who achieve HBV DNA levels of less than 4 log copies/ml (<2,000 IU/ml) at week 4. For those who do not achieve this level, the authors advise that therapy be modified. Alternatively, one can allow a later second HBV DNA measurement to be made at week 16 because their data suggested that this does not increase the probability of developing drug resistance.

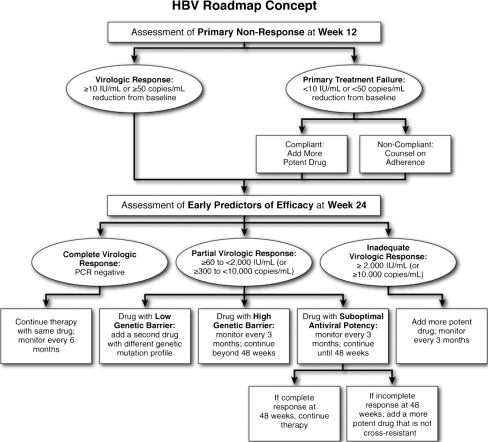

On the basis of the available evidence supporting the predictive value of on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels, a “roadmap” algorithm of practical guidelines that recommended quantitative HBV DNA monitoring at weeks 12 and 24, during which decisions may be made for optimizing therapeutic outcomes, has been proposed (Fig. 3) [17]. This strategy involves measuring HBV DNA levels at week 12 to determine primary treatment failure (defined as a decline in HBV DNA levels of <1 log10 IU/ml), and again at treatment week 24 to determine whether adjustment to therapy is required. Virologic response at treatment week 24 is categorized using the following definitions: complete (HBV DNA level <60 IU/ml), partial (HBV DNA level 60 to <2,000 IU/ml), and inadequate (HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/ml).

Fig. 3.

HBV treatment roadmap: on-virologic responses and their management in patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction. Reprinted with permission from Keeffe et al. [17]

For patients with a complete virologic response, continued therapy with the same drug is recommended, with repeat testing at 24-week intervals at the physician’s discretion. The addition of an appropriate non-cross-resistant second drug should be considered to prevent the emergence of resistance and viral breakthrough in patients with a partial response who are treated with a drug with a low genetic barrier to resistance (e.g., lamivudine). In contrast, patients who demonstrate a partial response while receiving treatment with a potent drug with a high genetic barrier (e.g., entecavir) should undergo repeated monitoring at 12-week intervals to be continued beyond 48 weeks. In patients with a partial response who have been treated with a drug with a delayed antiviral effect and a relatively high barrier to resistance (e.g., adefovir), monitoring should be repeated at 12-week intervals. If the response remains partial or becomes inadequate at week 48, a change in therapy should be undertaken unless HBV DNA levels have been decreasing steadily and are nearly undetectable. If the response becomes complete at week 48, therapy can be continued. Finally, patients with an inadequate virologic response require a change to a more efficacious drug or the addition of a second drug, preferably one without cross-resistance to the continued drug. Once this change has been made, patients should undergo monitoring at 12-week intervals.

The “roadmap” algorithm of practical guidelines for HBV DNA monitoring is in alignment with on-treatment monitoring and treatment adjustment recommendations by regional liver society guidelines for the management of CHB [1–3]. Previous treatment guidelines have provided some limited discussion of on-treatment monitoring. The 2008 Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver practice guidelines recommended that, during therapy, HBV DNA levels should be monitored at least every 12 weeks, regardless of the treatment modality used [1]. Similarly, the recently published 2008 European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines recommended that serum HBV DNA levels should be assessed every 12 weeks in patients treated with an NA [3]. Finally, the 2007 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines recommended that patients receiving NA therapy should have their HBV DNA levels measured every 12–24 weeks [2]. Collectively, these guidelines published by the world’s three largest liver societies concur that the first assessment point for on-treatment monitoring of HBV DNA levels should occur at week 12 after treatment initiation and continue every 12–24 weeks thereafter.

Conclusion

Durable HBV DNA suppression is a critical determinant of treatment outcome, and evidence from clinical studies of CHB shows that on-treatment HBV DNA levels can predict response to oral antiviral therapy. Substantial evidence from clinical studies has validated 24 weeks as a useful time point for on-treatment monitoring for lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, and telbivudine. The optimal time for on-treatment monitoring of tenofovir remains to be determined. Based on clinical evidence, regional liver society guidelines recommend that on-treatment monitoring of HBV DN levels should occur at week 12 to assess compliance and every 12–24 weeks thereafter to ascertain virologic response to treatment. Additional studies are needed to investigate the value of earlier time points in predicting successful outcomes.

Ultimately, optimal time points for on-treatment monitoring are dependent on the unique properties of each individual NA (e.g., potency, viral kinetics, genetic barrier/resistance profile), and further study will help refine recommendations for on-treatment monitoring based on these variables. Regardless, on-treatment monitoring represents a powerful tool to identify patients at risk of treatment failure and provides an opportunity for early treatment modification to improve outcomes and reduce the risk of antiviral resistance.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support in the development of this manuscript was provided by Kathleen Covino, PhD. This study has been supported by an independent educational grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb Company through the ACT-HBV Initiative.

References

- 1.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, et al., for the Chronic Hepatitis B Guideline Working Party of the Asian-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int 2008;2:263–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, et al., for the Cirrhosis Asian Lamivudine Multicentre Study Group. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521–1531 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, et al., for the Globe Study Group. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2576–2588 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Liaw YF, Gane E, Leung N, Zeuzem S, Wang Y, Lai CL, et al., for the GLOBE Study Group. 2-year GLOBE trial results: telbivudine is superior to lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2009;136:486–495 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zeuzem S, Gane E, Liaw YK, Lim SG, DiBisceglie A, Buti M, et al. Baseline characteristics and early on-treatment response predict the outcomes of 2 years telbivudine treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;51:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bristol Myers-Squibb. Entecavir AVDAC briefing document; 2005. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/ac/05/briefing/2005-4094B1_01_BristolMyersSquibb-entecavir.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2009

- 9.Lee HW, Kim HJ, Kim MH, Kim KA, Lee JS, Sul HR, et al. Entecavir induced HBV DNA suppression at 12 weeks in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B is a good predictive factor for virological response at 48 weeks Hepatology 200848Suppl741A18571815 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reijnders JG, Leemans WF, Hansen BE, Pas SD, Man RA, Schutten M, et al. On-treatment monitoring of adefovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B: virologic response can be assessed at 24 weeks. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zöllner B, Schäfer P, Feucht HH, Schröter M, Petersen J, Laufs R. Correlation of hepatitis B virus load with loss of e antigen and emerging drug-resistant variants during lamivudine therapy. J Med Virol. 2001;65:659–663. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier J, Bourne EJ, Lutz MW, Crowther LM, Dienstag JL, Brown NA, et al. Quantitation of hepatitis B viremia and emergence of YMDD variants in patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with lamivudine. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1757–1762. doi: 10.1086/315147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2001;34:785–791. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadziyannis A, Mitsoula PV, Hadziyannis SJ. Prediction of long-term maintenance of virologic response during lamivudine treatment in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;46(Suppl):667A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pritchett S, Wong DK, Yim C, Mazzulli T, Heathcote EJ. Factors affecting response to adefovir treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B and lamivudine resistance. Hepatology. 2007;46(Suppl):675A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heathcote EJ, Gane E, DeMan R, Lee S, Flisiak R, Manns MP, et al. A randomized, double-blind, comparison of tenofovir DF (TDF) versus adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) for the treatment of HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B (CHB): study GS-US-174-0103. Hepatology. 2007;46:861A. doi: 10.1002/hep.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS, Dieterich DT, Esteban-Mur R, Gane EJ, et al. Report of an international workshop: roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Archimandritis AJ. Current treatment indications and strategies in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6902–6910. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen MH, Keeffe EB. Chronic hepatitis B: early viral suppression and long-term outcomes of therapy with oral nucleos(t)ides. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaw YF. On-treatment outcome prediction and adjustment during chronic hepatitis B therapy: now and future. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB, for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology 2009;49:1335–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) Hepatitis C Working Party Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus statements of the diagnosis, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:615–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kau A, Vermehren J, Sarrazin C. Treatment predictors of a sustained virologic response in hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:634–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eijk AA, Niesters HG, Hansen BE, Heijtink RA, Janssen HLA, Schalm SW, et al. Quantitative HBV DNA levels as an early predictor of nonresponse in chronic HBe-antigen positive hepatitis B patients treated with interferon-alpha. J Viral Hepatol. 2006;13:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrillo RP, Lai CL, Liaw YF, Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Schalm SW, et al. Predictors of HBeAg loss after lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2002;36:186–194. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan HL, Wang H, Niu J, Chim AM, Sung JJ. Two-year lamivudine treatment for hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson AJ, Ayres A, Yuen L, Bartholomeusz A, Bowden DS, Iser DM, et al. Lamivudine resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B: role of clinical and virological factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1078–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai CL, Leung N, Teo EK, Tong M, Wong F, Hann HW et al., for the Telbivudine Phase II Investigator Group. A 1-year trial of telbivudine, lamivudine, and the combination in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2005;129:528–536 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Yuen MF, Fong DY, Wong DK, Yuen JC, Fung J, Lai CL. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels at week 4 of lamivudine treatment predict the 5-year ideal response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1695–1703. doi: 10.1002/hep.21939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tenney DJ, Pokornowski KA, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Eggers BJ, Fang J, et al. Entecavir maintains a high genetic barrier to HBV resistance through 6 years in naïve patients. J Hepatol. 2009;50(Suppl):S10. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(09)60022-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–1514. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, et al. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naïve patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:1656–1665. doi: 10.1002/hep.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenney DJ, Pokornowski KA, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Eggers BJ, Fang J, et al. Long-term resistance profile of entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B from worldwide and Japanese development programs. Proceedings of the Conference of Hepatitis C and B Virus: Resistance to Antiviral Therapies; 2006 Feb 14–16; Paris, France. Available from: http://www.easl.ch/hepatitis-conference/program/session1.asp. Accessed 2 June 2009

- 34.Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, et al. Entecavir therapy for up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han SH, Chang TT, Chao YC, Yoon SK, Gish RG, Cheinquer H, et al. Five years of continuous entecavir for nucleoside-naïve HBeAg(+) chronic hepatitis B: results from study ETV-901. Abstract No.: OP-48. Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease; 2009 Mar 20–24; Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.isvhld2009.org/pdfs/sunday_March22_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2009

- 36.Ma H, Ren JB, Li HY, Wang Y, Wang RL, Liang L, et al. Week 24 suppression of HBV in entecavir-treated chronic hepatitis B patients in whom lamivudine treatment failed is associated with efficacy at week 48. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2007;21:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu CW, Chen YC, Liaw YF, Gane E, Manns M, Zeuzem S, et al. Prolonged efficacy and safety of 3 years of continuous telbivudine treatment in pooled data from GLOBE and 015 studies in chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2009;50:S331. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(09)60913-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan HL, Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Lai CL, Cho M, Moon YM, et al., for the 018 Study Group. Treatment of hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis with telbivudine or adefovir: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:745–754 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Leung N, Peng CY, Hann HW, Sollano J, Lao-Tan J, Hsu CW, et al. Early hepatitis B virus DNA reduction in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B: a randomized international study of entecavir versus adefovir. Hepatology. 2009;49:72–79. doi: 10.1002/hep.22658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locarnini S, Qi X, Arterburn S, Snow A, Brosgart CL, Currie G, et al. Incidence and predictors of emergence of adefovir resistant HBV during four years of adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) J Hepatol. 2005;42(Suppl):17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M et al., for the Adefovir Dipivoxil 438 Study Group. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1743–1751 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Heathcote J, George S, Gordon JP, Bronowicki J, Sperl R, Williams P, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: week 72 TDF data and week 24 adefovir dipivoxil switch data (study 103) J Hepatol. 2008;48:S32. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(08)60074-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcellin P, Jacobson I, Habersetzer F, Senturk H, Andreone P, Moyes C, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for the treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: week 72 TDF data and week 24 adefovir dipivoxil switch study (study 102) J Hepatol. 2008;48:S26. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(08)60059-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snow-Lampart S, Chappell B, Curtis M, Zhu Y, Heathcote J, Marcellin P, et al. Week 96 resistance surveillance for HBeAg positive and negative subjects with chronic HBV infection randomized to receive tenofovir DF 300 mg qd. Abstract No.: OP-82. Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease; 2009 Mar 20–24; Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.isvhld2009.org/pdfs/sunday_March22_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2009