Abstract

Purpose

Abdominal wall nerve injury as a result of trocar placement for laparoscopic surgery is rare. We intend to discuss causes of abdominal wall paresis as well as relevant anatomy.

Methods

A review of the nerve supply of the abdominal wall is illustrated with a rare case of a patient presenting with paresis of the internal oblique muscle due to a trocar lesion of the right iliohypogastric nerve after laparoscopic appendectomy.

Results

Trocar placement in the upper lateral abdomen can damage the subcostal nerve (Th12), caudal intercostal nerves (Th7–11) and ventral rami of the thoracic nerves (Th7–12). Trocar placement in the lower abdomen can damage the ilioinguinal (L1 or L2) and iliohypogastric nerves (Th12−L1). Pareses of abdominal muscles due to trocar placement are rare due to overlap in innervation and relatively small sizes of trocar incisions.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall is mandatory in order to avoid the injury of important structures during trocar placement.

Keywords: Abdominal, Surgical-technical, Complications, Instruments-technical, Appendix, Hernia

Introduction

Nerve injury of the abdominal wall is one of the many complications of abdominal surgery. In conventional surgery, lesions of the intercostal nerves after subcostal laparotomy are well known, resulting in paresis of the rectus abdominis muscle and bulging of the abdominal wall. After Pfannenstiel incisions in gynaecological surgery or open inguinal hernia surgery, injury of the iliohypogastric or ilioinguinal nerve often leads to chronic pain syndromes [1]. Nerve lesions of the abdominal wall in laparoscopic surgery are rare however, and reports in the literature are scarce [2, 3]. Nevertheless, these do occur and will cause pain and dysfunction [4–6]. We will illustrate the importance of knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall nerve supply with a patient case.

Case history

A 37-year-old male with a history of hydronephrosis and kidney stones presented at our emergency ward with pain in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. His complaints were diagnosed as acute appendicitis and laparoscopic appendectomy was performed. Three trocars were inserted at the following locations: subumbilical (10 mm), just superior to the symphysis (10 mm) and 3.0 cm cranial to and 3.2 cm medial to the right anterior superior iliac spine (5 mm). The infiltrated appendix was resected and the diagnosis of ‘appendicitis’ was confirmed by histology. The patient was discharged on the second postoperative day and no infectious complications were observed during follow up.

Two weeks after discharge, the patient complained of a swelling in the right groin. A suspected inguinal hernia was ruled out by ultrasound and the patient was examined again after 4 weeks. At this visit, a slight, though evident, swelling of approximately 5 × 7 cm was seen in the lower right groin. The swelling was soft at palpation without clear borders. Contraction of the abdominal muscles resulted in an increase of the bulging (Fig. 1) but the Valsalva manoeuvre did not. Furthermore, a clear hypoaesthesia was found at the level of the swelling, which could be referred to as the sensory distribution of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. At this stage, a motory dysfunction of the internal oblique muscle was suspected.

Fig. 1.

Pronounced swelling of the lower right groin during active flexion of the abdominal muscles. Scars of trocar placement are present craniomedial to the anterior superior iliac spine, subumbilical and cranial to the symphysis. Printed with the patient’s permission

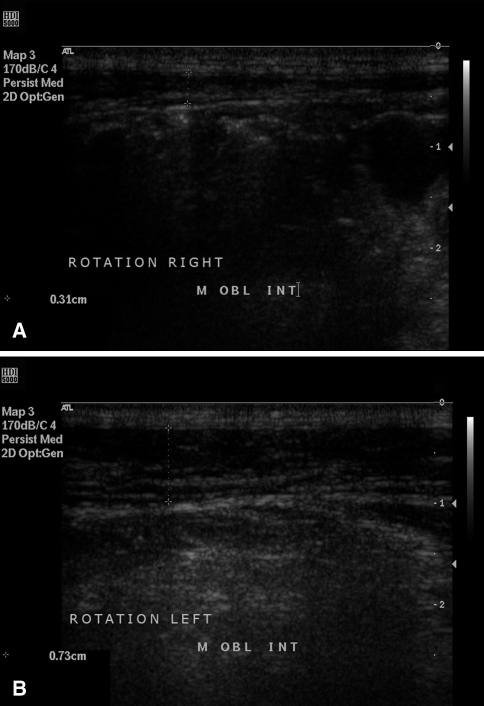

A second ultrasound investigation was performed to assess the function of the right internal oblique muscle with contralateral comparison. At rest, the transverse diameter of the interior oblique muscle was clearly diminished (Fig. 2). This decrease in diameter proved to be more evident during contralateral sit-ups, showing a relative decrease of almost 60% (3.1 vs. 7.3 mm, Fig. 3a, b). No protrusion of abdominal contents into the inguinal canal was observed during the Valsalva manoeuvre, dismissing the diagnosis of ‘inguinal hernia.’ For further evaluation of the suspected nerve injury, somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) were assessed. Testing of the lateral branches of both iliohypogastric nerves showed a clear delay in cortical response (47.2 ms right vs. 40.4 ms left), suggesting partial lesion of the right iliohypogastric nerve.

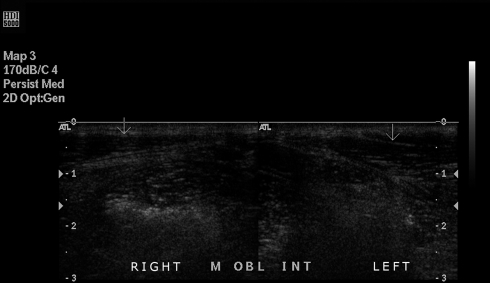

Fig. 2.

Ultrasonography at rest: diminishment in thickness of the right interior oblique muscle in comparison to the left side

Fig. 3.

Ultrasonography during contralateral sit-ups: right side showing relative diminishment in muscle thickness compared to the left side

Three months after surgery, the patient reported having sensations ‘like electrical current’ at the site of the swelling about two times a week lasting 1–2 s. At physical examination, the swelling appeared less pronounced than previously observed. Six months postoperatively, the patient reported his feelings of ‘electrical current’ to have subsided both in intensity and in frequency, now presenting about three times a month. The swelling could no longer be observed (Fig. 4) and, although hypoaesthesia was still present, pinprick testing of the right region was only slightly less sharp compared to the left. Apparently, partial recovery of motory and sensory innervation had led to normal functioning of the internal oblique muscle.

Fig. 4.

No swelling 6 months after surgery. Printed with the patient’s permission

Anatomy of the abdominal wall nerves at the level of the upper abdomen

Trocar placement in the upper lateral abdomen can damage the subcostal nerve (Th12), caudal intercostal nerves (Th7–11) and ventral rami of the thoracic nerves (Th7–12). The subcostal and caudal intercostal nerves cross the medial alignment of the rib cage with the associated arteries and run in the neurovascular plane between the transverse and internal oblique muscles. Lateral branches perforate the intercostal and external oblique muscles and innervate the serratus anterior and external oblique muscles, whilst medial branches innervate the rectus abdominis muscles. Lateral and anterior cutaneal branches provide sensory innervation of the respective skin areas [7, 8].

Korenkov described a case of combined abdominal wall paresis and incisional hernia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to an extension of the incision at the stone extraction site. In this obese patient, a protrusion was noticed at the right mid-anterior abdominal wall 3 months after the initial operation. Neurologic injury was confirmed by electromyography (EMG) and the hernia was consequently repaired [2]. Other reported causes of abdominal wall pareses include diabetic neuropathy, infections with herpes zoster virus and Borrelia burgdorferi, herniation of intervertebral discs at thoracic or lumbar levels and retroperitoneal processes [9–13].

Anatomy of the abdominal wall nerves at the level of the lower abdomen

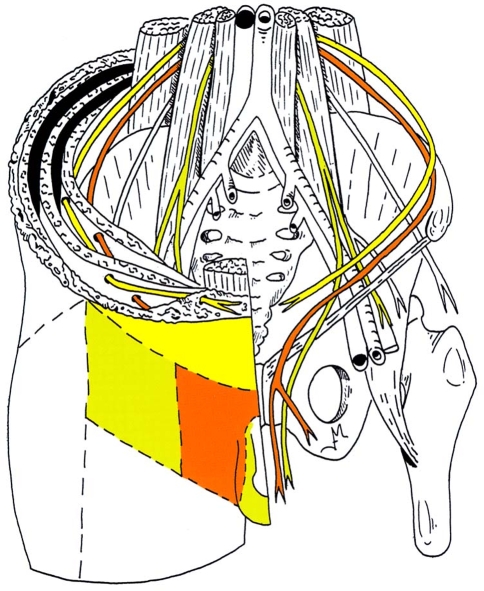

The first (or second) lumbar root (L1) gives rise to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, the latter also originating from Th12. Positions of the lateral emergence of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves have been mapped in human cadaver studies [14, 15]. The iliohypogastric nerve is a mixed nerve (sensory and motory) that runs parallel to the ilioinguinal nerve until it perforates the psoas muscle and then descends towards the crista iliaca, anterior to the quadratus lumborum (Fig. 5) [16]. The iliohypogastric nerve enters the abdominal wall at 2.1 ± 1.8 cm medial and 0.9 ± 2.8 cm inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine [1]. It then descends through the transverse abdominal muscle anterior to the internal oblique muscle and the inguinal ring, giving off branches to both muscles. The sensory area supplied by this nerve is restricted to skin at the lateral side of the hip (r. cutaneus lateralis) and the inguinal region and skin cranial to the symphysis pubis (r. cutaneus anterior). It has been found to terminate at 3.7 cm lateral to the midline and 5.2 cm superior to the pubic symphysis [4, 14].

Fig. 5.

Innervation of the ventral abdominal wall by iliohypogastric (light grey), ilioinguinal (dark grey) and genitofemoral nerves (medium grey). In the online version, the nerves are represented in yellow, orange and green, respectively. Reprinted with permission [16]

The course of the ilioinguinal nerve is caudal and parallel to the iliohypogastric nerve. It enters the abdominal wall at 3.1 ± 1.5 cm medial and 3.7 ± 1.5 cm inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine [14]. Identical to the iliohypogastric nerve, it supplies motory innervation to the transverse abdominal and internal oblique muscles. Sensory branches include the r. cutaneus anterior, which perforates the external oblique muscle just caudal to the anterior superior iliac spine, and the nn. labiales/scrotalis anteriores, which supply, e.g. the labia majora/scrotum and the skin of the medial upper leg [4]. Damage to the ilioinguinal nerve is an infamous complication of inguinal hernia surgery. It can lead to the development of chronic neuralgia or nerve entrapment syndromes [5, 6].

Pareses of the transverse abdominal and internal oblique muscles are quite rare due to the innervation by both the ilioinguinal and the iliohypogastric nerves. However, in order to minimise the risk of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve injuries, Whiteside et al. concluded that trocars should be placed at 2 cm above an imaginary line between the right and left anterior superior iliac in order to be able to avoid injury in most patients [14].

Discussion

This is the first reported case of abdominal wall paresis as a direct result of trocar placement. Generally, abdominal wall paresis presents as a swelling and may be accompanied by complaints of pain or other sensory changes. The lower part of the abdomen is affected more often than the upper part due to the high number of surgical procedures in this region and to the differences in nerve supply. In obese patients, swellings may not be evident at clinical examination and will remain undiagnosed. If a history of (recent) surgical trauma is absent, the blood levels of glucose and infection parameters can help exclude diabetic neuropathy and herpes zoster virus as causal agents. If neuroborreliosis is suspected, referral to a neurologist for Borrelia burgdorferi serology, Western blot and liquor analysis is warranted. Inspection of the vertebral column and neurological examination are needed in order to exclude the possibility of, for example, intervertebral disc herniation. Nerve function can be tested by EMG, SSEPs measurements or quantitative sensory testing.

Spontaneous recovery of nerve function has been reported in several cases [10, 11, 13, 17]. Initial treatment should, therefore, be conservative. If spontaneous recovery remains absent, large swellings or bulging due to paresis may lead to mechanical complaints. The presence of abdominal hernia can be excluded by computed tomography or ultrasonography, the latter allowing the dynamic investigation of abdominal muscles. Bulging or incisional hernia can be treated conservatively by increasing abdominal support, e.g. by wearing a fitted corset. Surgical reinforcement of the abdominal wall may eventually be necessary, especially in cases of persistent pain.

Nerve injury associated pain can cause significant discomfort in patients and require treatment. Injection with short-acting local anaesthetics is an inexpensive and easy method to identify the damaged nerve [5, 6]. However, overlap of nerve distribution areas influence the interpretation of results and the test of choice, therefore, depends on the site of injury and the suspected lesion. Pain can be relieved by the local injection of anaesthetics and anti-inflammatory agents, selective nerve blockage, neurolysis or neurectomy [4–6].

In conclusion, since the abdominal wall can be considered as an organ with its own morphology and physiology, for both conventional and laparoscopic surgery, a thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall is essential to avoid injury of important structures during trocar placement. Nerve injury results in disturbances of sensory and/or motory innervation, the latter leading to paresis of the abdominal wall and undermining the benefits of minimal invasive surgery.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Luijendijk RW, Jeekel J, Storm RK et al (1997) The low transverse Pfannenstiel incision and the prevalence of incisional hernia and nerve entrapment. Ann Surg 225:365–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Korenkov M, Rixen D, Paul A et al (1999) Combined abdominal wall paresis and incisional hernia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 13:268–269 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cardosi RJ, Cox CS, Hoffman MS (2002) Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 100:240–244 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mumenthaler M, Schliack H (1982) Läsionen Peripherer Nerven: Diagnostik und Therapie, 4th edn. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart

- 5.Stulz P, Pfeiffer KM (1982) Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Arch Surg 117:324–327 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Melville K, Schultz EA, Dougherty JM (1990) Ilionguinal–iliohypogastric nerve entrapment. Ann Emerg Med 19:925–929 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Frick H, Leonhardt H, Starck D (1991) Human anatomy 1. General anatomy, special anatomy: limbs, trunk wall, head and neck, 1st edn. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart

- 8.Schlenz I, Burggasser G, Kuzbari R et al (1999) External oblique abdominal muscle: a new look on its blood supply and innervation. Anat Rec 255:388–395 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lempert T, Skotzek B (1988) Bauchwandparese bei thorakaler diabetischer neuropathie. Nervenartzt 59:48–49 [PubMed]

- 10.McLoughlin R, Waldron R, Brady MP (1988) Post-herpetic abdominal wall herniation. Postgrad Med J 64:832–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mormont E, Esselinckx W, De Ronde T et al (2001) Abdominal wall weakness and lumboabdominal pain revealing neuroborreliosis: a report of three cases. Clin Rheumatol 20:447–450 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Billet FPJ, Ponssen H, Veenhuizen D (1989) Unilateral paresis of the abdominal wall: a radicular syndrome caused by herniation of the L1–2 disc? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 52:678–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Meyer F, Feldmann H, Töppich H et al (1991) Unilaterale Parese der Bauchwandmuskulatur durch einen thorakalen Bandscheibenvorfall. Zentralbl Neurochir 52:137–139 [PubMed]

- 14.Whiteside JL, Barber MD, Walters MD et al (2003) Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:1574–1578 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Avsar FM, Sahin M, Arikan BU et al (2002) The possibility of nervus ilioinguinalis and nervus iliohypogastricus injury in lower abdominal incisions and effects on hernia formation. J Surg Res 107:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lange JF, Kleinrensink GJ (2002) Surgical anatomy of the abdomen—part 1, 1st edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam

- 17.Montagna P, Medori R, Liguori R et al (1985) Abdominal neuropathy after renal surgery. Ital J Neurol Sci 6:357–358 [DOI] [PubMed]