Abstract

Primary kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) on a series of carboxylic acid-catalyzed protonation reactions of aryl-substituted α-methoxystyrenes (X-1) to form oxocarbenium ions have been computed using the Kleinert variational second-order perturbation theory (KP2) in the framework of Feynman path integrals (PI) along with the potential energy surface obtained at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Good agreement with the experimental data was obtained, demonstrating that this novel computational approach for computing KIEs of organic reactions is a viable alternative to the traditional method employing Bigeleisen equation and harmonic vibrational frequencies. Although tunneling makes relative small contributions to the lowering of the free energy barriers for the carboxylic acid catalyzed protonation reaction, it is necessary to include tunneling contributions to obtain quantitative estimates of the KIEs. Consideration of anharmonicity can further improve the calculated KIEs for the protonation of substituted α-methoxystyrenes by chloroacetic acid, but for the reactions of the parent and 4-NO2 substituted α-methoxystyrene with substituted carboxylic acids, the correction of anharmonicity overestimates the computed KIEs for strong acid catalysts. In agreement with experimental findings, the largest KIEs are found in nearly ergoneutral reactions, ΔGo ≈ 0, where the transition structures are nearly symmetric and the reaction barriers are relatively low. Furthermore, the optimized transition structures are strongly dependent on the free energy for the formation of the carbocation intermediate, i.e., the driving force ΔGo, along with a good correlation of Hammond shift in the transition state structure.

I. Introduction

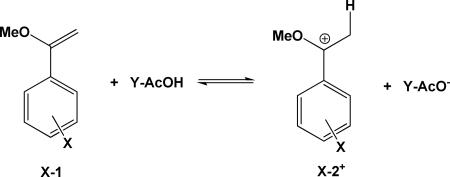

Brønsted acid-catalyzed proton transfer reactions at carbon of conjugated alkenes play an important role in chemical and biological processes.1 For example, the bacterial squalene to hopene polycyclization reaction, a process closely related to the biosynthesis of cholesterol, is initiated by the rate-limiting proton transfer from an aspartic acid residue to the 2,3-alkene.2-4 An understanding of structure-activity relationship by changing the substituents at the proton donor and acceptor compounds can provide useful insights into the structures of transition state for reactions that generate reactive carbenium ion intermediates both in biological systems and in aqueous solution. In principle, kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) provide a direct probe of the transition state structure;5 however, there have been relatively few systematic studies on proton transfer reactions at carbon. The accompanying experimental studies of primary KIEs for the protonation reactions of aryl substituted α-methoxystyrenes X-1 by a series of substituted acetic acids (Y-AcOH)6 produce a unique set of experimental data for theoretical analysis to explain the changes in KIE on proton transfer reactions at carbon due to variations in reaction driving force ΔGo. In this article, we use a novel path-integral method based on Kleinert second-order perturbation (KP2) theory to analyze computational results on the same series of reactions to shed light on the origin of the observed trends in isotope effects.

Recently Tsang and Richard reported a fast and general method for determining primary product (PIE) and kinetic isotope effects on proton transfer at carbon in hydroxylic solutions.7 That work has been extended to include a broader range of substituents both on the proton donor and on the vinyl ether proton acceptor X-1.6 It was found that the largest PIEs are observed for the protonation of 4-MeO-1, which is the most basic and reactive vinyl ether compound in the series. As the basicity decreases in X-1, the experimental PIEs show strong dependence on the reaction driving force. These experimental findings are consistent with a Hammond effect on the transition state structure of substituted X-1 and the strength in acidity of the proton donor.

In this study we perform calculations on the protonation of aryl substituted X-1 and substituted acetic acids that have been investigated experimentally.6,7 Our study is based on Kleinert's second order variational perturbation theory8,9 (KP2) for the centroid density of Feynman path integrals10 to treat nuclear quantum effects. Our approach goes beyond the traditional method for computing KIE employing the Bigeleisen equation11-13 by including contributions from tunneling and vibration anharmonicity. A particularly attractive feature of the KP theory is that the variational perturbation is exponentially and uniformly convergent.9 Furthermore, with the instantaneous normal mode approximation,14,15 the nuclear quantum effects can be decomposed into anharmonicity and tunneling contributions, providing further insights into the origin of substituent effects on KIE. Although the first order KP theory (KP1), which is equivalent to the variational method independently introduced by Giachett and Tognetti16 and by Feynman and Kleinert17 (GTFK), has been extensively used in a wide range of applications, higher order KP theory has only been used in limited applications on model systems. We have recently implemented the second and third order Kleinert perturbation theory8,9 for molecular systems, in which the path integrals have been integrated analytically.14,15,18 This computational procedure is essentially an automated path integral method and integration free since there is no need to carry out discrete Monte Carlo or molecular dynamics simulations. Consequently, it allows the Kleinert perturbation theory (up to the third order) to be conveniently used in practical applications in large molecular systems.

The goals of this study are two folds. First, we aim to provide a theoretical understanding of the trends of the observed primary KIEs on the protonation of X-1 by different acids.6 Secondly, we wish to illustrate the accuracy and applicability of the automated integration-free path-integral (AIF-PI) method14 based on KP2 theory for determining kinetic isotope effects of organic reactions using a potential energy surface directly obtained from density functional theory (DFT). We also show that the present KP theory offers an alternative to the traditional approach to compute KIEs for organic reactions using the Bigeleisen and Goeppert-Mayer formalism,11-13,19 in which anharmonicity and tunneling contributions are neglected. Of course, the latter effects can be incorporated into the calculation using semiclassical models based on transition state theory, and anharmonic contributions can be analyzed by other separate approaches.20,21 Nevertheless, the ability to incorporate these effects in a unified theoretical framework in path integral calculations to efficiently determine KIEs for chemical reactions along with the use of ab initio and DFT calculations can be of great use for organic reactions, making use of Kleinert's variational perturbation theory.8,9

The paper is organized as follows. We first present a brief summary of the theoretical background, focusing on computation of kinetic isotope effects. In section III, the computational details are provided, followed by results and discussions in section IV. In section V, we summarize the major findings from this study.

II. Theoretical Background

The most widely used formalism to compute kinetic isotope effects is the Bigeleisen equation, in which the KIE is determined by the use of the harmonic vibrational frequencies, neglecting quantum tunneling:11-13,19

| (1) |

where νXi is the ith normal mode frequency for an X isotopomer, the superscript ≠ denotes the transition state and the subscript H and D specify the light and heavy isotopes, ui = hνi / 2kBT, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, ħ is Planck's constant divided by 2π, and the factor is the ratio of the imaginary frequencies at the transition state. Eq 1 has been remarkably successful for organic reactions and the effects of tunneling can be corrected by semiclassical methods including multidimensional contributions based on transition state theory.20

To go beyond the harmonic approximation and to include quantum tunneling effects in the framework of Feynman path integrals, the Bigeleisen equation can be rewritten as follows:18

| (2) |

where WX (zX) is the centroid effective potential22-24 along the reaction coordinate zX calculated from the path integrals for isotopomer X, and and are its values at the transition state and at the reactant state, respectively. Note that eq 2 reduces to eq 1 when the centroid potential is calculated in the harmonic approximation (and neglecting tunneling effects; Appendix B in Ref. 18 provides a proof). Moreover the mass-dependent nature of the centroid effective potential in eq 2 distinguishes it from the classical mechanical potential of mean force in transition state theory, which is mass-independent. Eq 2 is derived based on path-integral quantum transition state theory (PI-QTST),22-24 and the reaction coordinate zX is defined by the centroid positions of atomic coordinate {x̄k}, which is the imaginary time-average . The mass-dependent property of the centroid potential in the formulation of the path-integral quantum transition-state theory (PI-QTST) has been applied to chemical reactions in condensed phases.22-30 With the treatment of solvent effects by a dielectric continuum,31,32 we determined the KIE for the proton transfer reactions along the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC)33 path using the AIF-PI method.14,15

Consequently, the main task in our approach, employing the Kleinert perturbation theory, is to determine the centroid effective potential W(z) along the reaction coordinate z.14,15 Although this new approach appears to be very different from the familiar Bigeleisen equation,11-13,19 the computational procedure is rather straightforward. As in calculations using eq 1, one first optimizes the reactant state and the transition state structures and determines their harmonic vibrational frequencies. Without including tunneling and anharmonicity effects, eq 1 can be used to estimate KIE at this stage.13 In our approach, we further carry out the IRC path calculation to trace the reaction path z from the transition sate to the reactant and product state, respectively. In principle, this is required in the use of the Bigeleisen equation for validation of the transition state. The additional calculation needed to construct W(z) along z is to determine the free energy difference between the use of harmonic and anharmonic frequencies plus tunneling contributions by means of centroid path integral method10,22-24 using Kleinert perturbation theory.8,9,14,15 This is done by using the one-dimensional potential in each normal mode coordinate for the 3N-6 normal modes, which is automated in our program.14 If the geometry of the transition state is not significantly modified, as in the present case, in the centroid “quantum” reaction coordinate22-24 compared with that in the IRC (classical) path, one only needs to perform KP2 calculations at the reactant and transition state geometry, without necessarily following the entire IRC path. The following two paragraphs contain further computational details and the reader who is not interested in these technical issues may skip directly to the next section.

Kleinert's variational perturbation theory provides a systematic approach to determine the path-integral centroid potential W(z).8-10 The derivation for KP theory can be found in Kleinert's textbook9 and our computational procedure has been described previously.14,15,18 In essence, KP theory systematically builds up anharmonic corrections to a harmonic reference state - not to be confused with the harmonic vibrational frequencies ν in eq 1 - defined by a trial angular frequency Ω to yield the nth-order perturbation (KPn) approximation to the centroid effective potential ,9 which defines the canonical quantum mechanical partition function in path integral representation.10 The optimal choice of the trial frequency at a given order of KP expansion and at a particular centroid reaction coordinate is determined by the least-dependence of on Ω, which provides a variational approach to determine its optimal value.8,9,14,15,34 The KP theory implemented in the AIF-PI program is an analytical approach allowing the use of high-level ab initio or DFT methods to determine the internuclear potential energy function to perform ab initio path-integral calculations.14,15,18 It would be prohibitively expensive if discretized path-integral Monte-Carlo (PIMC) or centroid molecular dynamics (CMD) simulations34 are used for large systems such as the proton transfer reactions (more than 90 degrees of freedom) described here.

An especially attractive feature of KP theory is that if the potential energy surface of the system is expressed as a series of polynomials or Gaussian functions, the path integrals can be explicitly integrated and an analytic expression of the KPn centroid potential can be obtained for a given Ω.8,9 However, for multidimensional potentials, the trial frequency becomes a 3N × 3N matrix for N nuclei, which quickly becomes intractable computationally even at the second order perturbation (KP2) level. To render the KP theory computationally feasible for many-body systems, we make instantaneous normal mode (INM) approximation for a given nuclear centroid configuration {x̄k}.14,15 Thus, the multidimensional potential energy surface is effectively reduced to 3N one dimensional potentials along each INM coordinate, and the total centroid effective potential for N nuclei is simplified as:14

| (3) |

where V({x̄k}) is the 3N-dimensional potential energy surface, which is determined by DFT calculations in the present work, is the centroid potential for normal mode i. Although the INM approximation sacrifices some accuracy, in exchange, it allows analyses of quantum vibration and tunneling contributions to W(z) to gain chemical insight. Our previous studies show that the computational results employing the INM approximation can yield excellent results in comparison with systems for which the exact quantum results of vibration and tunneling are known.14,15.18 In practice, real frequencies from the INM analysis often yields positive wi with dominant contributions from zero-point energy. On the other hand, for imaginary frequencies in the INM, the values of wi are often negative, corresponding to tunneling.14,15,18 Finally, since ab initio or DFT potential surface along a given normal mode is used in the calculation of the centroid potential wi, anharmonicity contributions are naturally included in eq 3. Consequently, comparison of KIE computed using eqs 1 and 2 allows an evaluation of the significance of anharmonicity and tunneling in calculated kinetic isotope effects.

III. Computational Details

The molecular structures of the separate reactants (substituted acetic acids and aryl-substituted vinyl ethers), product ion, and the transition-state structures in aqueous solution were optimized using density-functional theory with the inclusion of the polarizable continuum model (PCM)31,32 for the treatment of the solvent effects. In all calculations, the hybrid B3LYP functional35-37 and the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set were used. Vibrational frequency analyses were performed to confirm the nature of the minimum and saddle points. All the electronic structure calculations were performed using the software package Gaussian 03.38 By default, Gaussian 03 uses united atom (UA) model to define the molecular cavity for the PCM model,38-40 in which a spherical cavity is placed on each heavy atom encompassing the hydrogen atoms attached to it. To prevent discontinuity of the potential energy surface during transition-state optimizations where the migrating proton is neither completely bonded to the donor (O—H) nor to the acceptor (C—H) atoms, we have chosen to use fixed atomic radii rather than a cavity defined by the isodensity surface. The UAKS radii optimized at the PB0/6-31G(d) level of theory39,40 are adopted in the present work except the donor oxygen and the acceptor carbon atoms, whose values have been adjusted to yield the experimental free energy of reaction for α-methoxystyrene and chloro-acetic acid. In addition, the hydrogen atoms bonded to the donor and acceptor atoms are explicitly represented in the PCM calculations. All atomic radii used in the present study are given as Supporting Information.

We used eq 2 to determine KIE values in this study. Since the molecular structures of the transition state and the reactant state on the original PCM-B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) potential energy surface (PES) are similar to those on the centroid PES (their difference is usually in the order of 10–2 Å),14,15,18 the molecular structures for the transition and reactant states in this paper were not re-optimized on the basis of the centroid potential.

In the present study in path-integral calculations, we express the potential energy surface along each INM coordinate by a twentieth order polynomial that is fitted to results from PCM-B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) calculations at a step size of 0.1 Å. The centroid potential is computed up to the second order of KP expansion. Thus, the notion for this level of theory is KP2/P20 and Pm denotes an mth order polynomial representation of the original PES of each normal mode coordinate. Through a series of tests,14,15,18 we found that KP2/P20 is generally a good choice for the AIF-PI method. The calculated values of the centroid potential are usually within a few percent from the exact values. To compute the anharmonicity contributions to the KIE, we quantized the following five nuclei: the donor oxygen (O1), the protium or deuterium (H1), and the three atoms of the terminal CH2 methylene group of X-1. The entire system is quantized (more than 30 nuclei) to obtain the imaginary normal mode for computing the tunneling contribution to the KIE. All computations are performed using the AIF-PI program implemented for use with Mathematica (Wolfram Research Inc., Mathematica, Versions 5 and 6, Champaign, IL). The analytic expression and program can be found in the Supporting Information of Ref. 14 and 15, which is conveniently connected with Gaussian03 calculations, and the program may also be obtained from the authors of this article.

IV. Results and Discussions

A. Comparison with experiments

Table 1 lists the bond distances of the transferring proton from the donor (O—H) and the acceptor (C—H) atom, and the experimental and computed PCM free energies of activation ΔG≠ and free energies of reaction ΔGo (driving force) for the twelve proton transfer reactions, consisting of the entire series of substituted acetic acids and two H-1 and 4-NO2-1, and one series of aryl-substituted α-methoxystyrene and chloroacetic acid. The computed total bond orders (Wiberg bond index41-43) of the acceptor and donor bonds and the imaginary frequencies of transition-state structures along with the differences in bond order and in bond lengths are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Optimized donor (O-H) and acceptor (C-H) bond lengths (Ǻ) at the transition states along with the calculated and experimental free energies of activation (kcal/mol) for the proton transfer reactions between substituted α-methoxystyrenes (X-1) and acetic acids (Y-CH2CO2H) at 25°C.a

| Reaction | TS structure | ΔG≠ | ΔGo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-1 | Y-CH2CO2H | R(O—H) | R(C—H) | Calc. | Expt. | Calc. | Expt. |

| 4-MeO- | Cl- | 1.3190 | 1.3224 | 14.6 | 15.2 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| H- | Cl- | 1.3557 | 1.2966 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 1.4247 | 1.2552 | 20.4 | 19.3 | 13.0 | 9.2 |

| 3,5-di-NO2- | Cl- | 1.4758 | 1.2318 | 22.6 | 21.1 | 16.3 | 12.2 |

| H- | di-Cl- | 1.3201 | 1.3225 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 1.4 | 3.4 |

| H- | NC- | 1.3421 | 1.3070 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| H- | Cl- | 1.3557 | 1.2966 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| H- | MeO- | 1.3928 | 1.2741 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 9.1 | 6.6 |

| H- | H- | 1.4188 | 1.2600 | 19.6 | 18.7 | 10.3 | 8.3 |

| 4-NO2- | di-Cl- | 1.3753 | 1.2837 | 18.4 | 17.6 | 8.6 | 7 |

| 4-NO2- | NC- | 1.4030 | 1.2676 | 19.7 | 19.1 | 12.3 | 8.6 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 1.4247 | 1.2552 | 20.4 | 19.3 | 13.0 | 9.2 |

| 4-NO2- | MeO- | 1.4754 | 1.2317 | 22.4 | 20.2 | 16.3 | 10.1 |

| 4-NO2- | H- | 1.5181 | 1.2145 | 23.7 | 21.4 | 17.5 | 11.9 |

See Supporting Information for details on the calculations of the potential energy surface and transition state optimization at the PCM-B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level.

Table 2.

Computed total bond orders of the acceptor (O—H) and donor (C—H) bonds Ptot, the difference in bond order, ΔP = P(C – H) – P(O – H), and in bond lengths (Ǻ), ΔR = R(C—H) - R(O—H) at the transition states, along with the imaginary frequencies, ω‡, for protium H and deuterium D (i cm−1).

| X-1 | Y-CH2CO2H | Ptot | ΔP | ΔR | ω‡(H) | ω‡(D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-MeO- | Cl- | 0.748 | 0.157 | 0.003 | 1211 | 916 |

| H- | Cl- | 0.754 | 0.204 | −0.059 | 1048 | 802 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 0.764 | 0.290 | −0.169 | 660 | 540 |

| 3,5-di-NO2- | Cl- | 0.770 | 0.344 | −0.244 | 411 | 365 |

| H- | di-Cl- | 0.744 | 0.156 | 0.002 | 1178 | 891 |

| H- | NC- | 0.750 | 0.186 | −0.035 | 1109 | 845 |

| H- | Cl- | 0.754 | 0.204 | −0.059 | 1048 | 802 |

| H- | MeO- | 0.762 | 0.250 | −0.119 | 867 | 680 |

| H- | H- | 0.767 | 0.281 | −0.159 | 724 | 585 |

| 4-NO2- | di-Cl- | 0.754 | 0.230 | −0.092 | 933 | 722 |

| 4-NO2- | NC- | 0.759 | 0.264 | −0.135 | 792 | 629 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 0.764 | 0.290 | −0.169 | 660 | 540 |

| 4-NO2- | MeO- | 0.773 | 0.345 | −0.244 | 402 | 357 |

| 4-NO2- | H- | 0.780 | 0.390 | −0.304 | 271 | 253 |

The trends of the computed free energies of activation for the proton transfer reactions of the various substituted aryl vinyl ethers (AVE) and substituted acetic acids in water represented by the PCM model are in excellent accord with the experimental data (Table 1), whereas the computed free energies of reaction are somewhat overestimated for the most endoergic reactions.6,44 The experimental barrier heights have been obtained from the observed rate constants at 25°C using transition-state theory (TST) and the experimental free energies of reaction are determined from the measured equilibrium constants.6,44 For comparison, the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) for ΔGo is 3.3 kcal/mol, and the RMSD in the calculated barrier height from the experimental results is 1.2 kcal/mol, in which the largest deviation is about 2 kcal/mol. Overall the computational results are in reasonable agreement with the experimental data, suggesting that the computational method used in the present study is adequate for treating the proton transfer reactions.6,44 Specifically, electron-withdrawing substituents on α-methoxystyrene (X-1) tend to increase the free-energy barriers, whereas increased acidity of the donor group accelerates the rate of reaction (Table 1). For the parent system, H-1 + AcOH, the computed and experimental ΔG≠ are 19.6 and 18.7 kcal/mol, respectively. The combined effects of the carbocation stabilization by the electron-donating group, 4-MeO-, at the transition state and the increased acidity of the donor acid by the electron-withdrawing chloro-group lower the free-energy barrier by 5.0 kcal/mol (to 14.6 kcal/mol), which may be compared with the experimental effect of 3.5 kcal/mol (15.2 kcal/mol). Conversely, the highest barriers are found in the reaction between 4-NO2-1 and acetate acid (the most endoergic of the reactions considered in this study) with a free energy barrier of 23.7 kcal/mol from computation and 21.4 kcal/mol from the experiment (Table 1).6,44

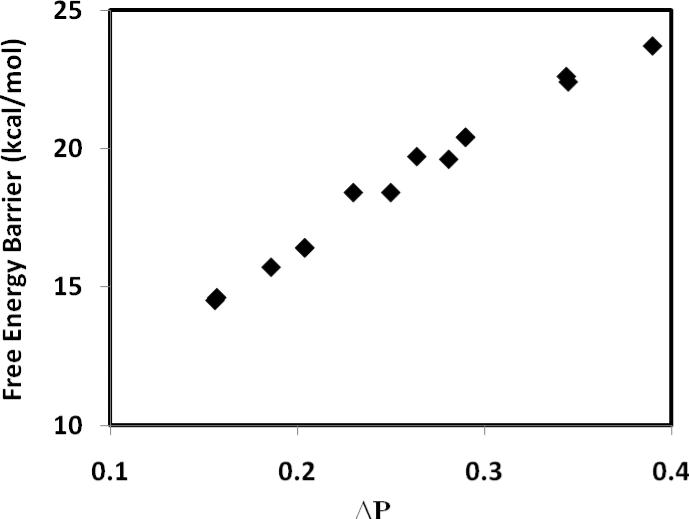

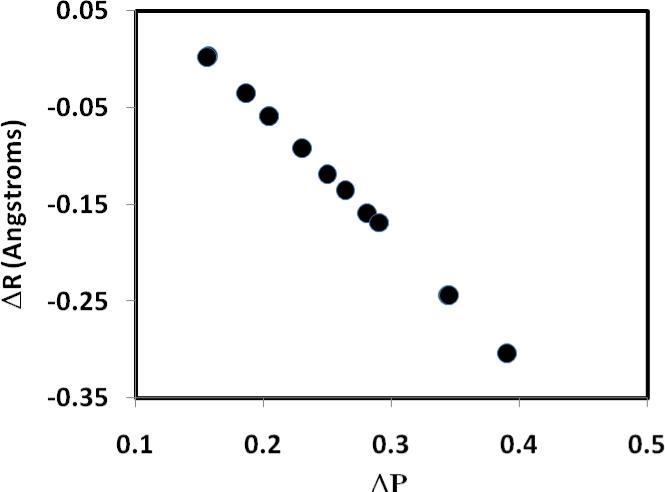

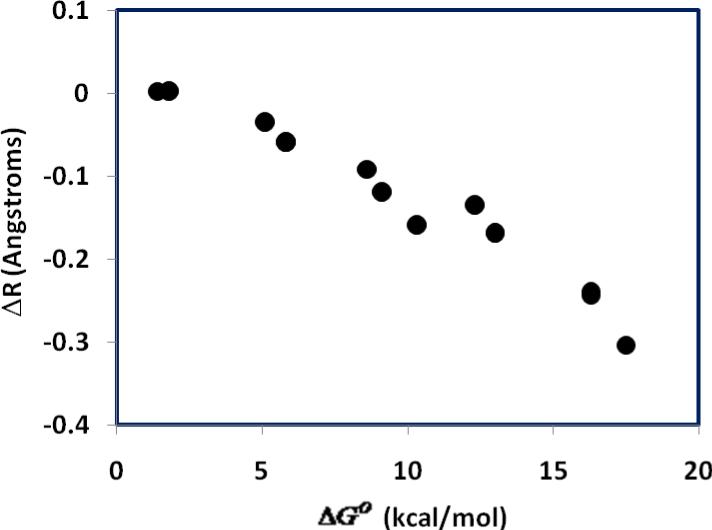

The agreement in the trend of free-energy barriers between theory and experiment is mirrored by structural variations and computed bond orders (Table 2). In general, reactions with smaller barriers are accompanied by transition-state structures that are more symmetric with a smaller difference in bond order (ΔP = P(C – H) – P(O – H)) between the acceptor bond and the donor bond (Figure 1). Furthermore, there is a strong linear correlation between the difference in bond order and the asymmetry between the acceptor and donor bond distances (ΔR = R(C – H) – R(O – H)) at the transition state (Figure 2). For the fastest reactions (4-MeO-1 + ClCH2CO2H and H-1 + Cl2CHCO2H), ΔR is nearly symmetric at 0.003 and 0.002 Å, respectively, and the difference in bond order ΔP is 0.157 and 0.156, respectively (Table 2). This is in excellent agreement with the conclusion from analyses of the observed kinetic (product) isotope effects, which also point to more symmetric transition states for reactions with low barriers.6 On the other hand, for the slowest reaction of the present study, 4-NO2-1 + CH3CO2H, the transition state is developed much later, characterized by a greater O—H bond length than that of the forming bond, C—H, (ΔR = –0.304 Å), and a difference in bond order of ΔP = 0.390 between the C—H and O—H bonds. Such a Hammond transition-state shift (Figure 3) has also been proposed based on experimental kinetic data in the accompanying paper.6 Interestingly, although there is significant variation in the difference in bond order between the donor and acceptor bonds at the transition states, the change in the total bond order over different substitutions is minimal (Table 2, column 3).

Figure 1.

Correlation between computed free energy barrier (kcal/mol) and the difference in bond order between the acceptor and donor bond (ΔP) at the transition state for the protonation reactions of substituted α-methoxystyrenes by carboxylic acids.

Figure 2.

Computed differences in bond length (ΔR) and in bond order (ΔP) at the transition state for the protonation reactions of substituted α-methoxystyrenes by carboxylic acids.

Figure 3.

Computed Hammond shifts in transition structure as illustrated by the difference in acceptor and donor distance from the transferring hydrogen (ΔR) with increasing endroergicity of reaction.

The structural variations are reflected by the computed imaginary frequencies at the transition states for the proton transfer reactions. Table 2 shows that the more symmetric and tighter transition states (indicated by small difference in ΔR) have the largest values in the imaginary frequency. In fact, a good correlation can be found between the frequency values (either for protium or deuterium) and the differences in bond order of these twelve reactions with an R2 (correlation coefficient for a linear relationship) of 0.993

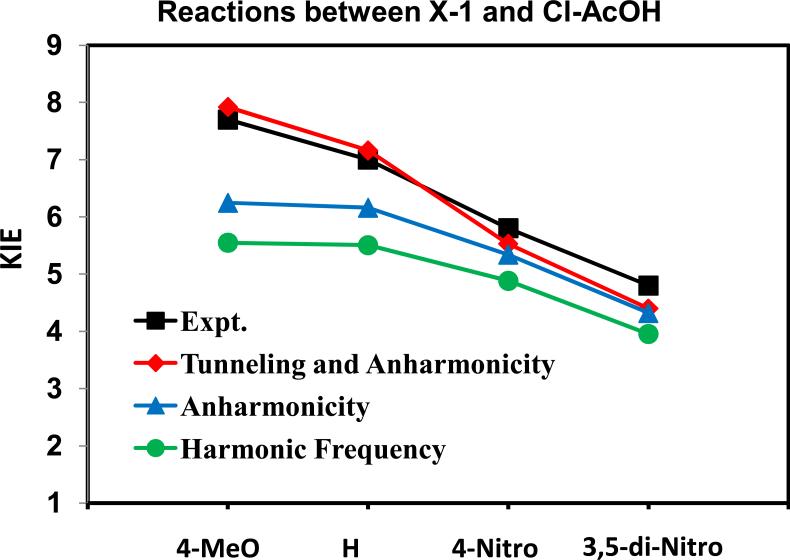

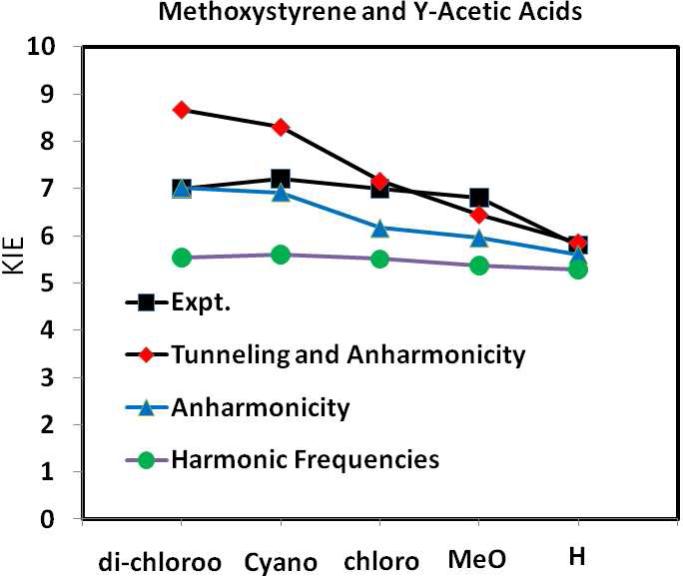

The experimental and computed KIE values for the twelve reactions are presented in Table 3. Overall, the agreement between the experiments and calculations is very good with a RMSD of 0.9. The trends observed for structures and bond orders at the transition states as well as the free-energy barriers are clearly reflected in the computed and measured KIEs. Specifically, reactions of the substrate (X-1) substituted with a strong electron-donating group (X = 4-MeO, and H) or reactions involving a strong carboxylic acids (Y = di-Cl, NC-, and Cl), for which the computed transition structures are nearly symmetrical, usually exhibit large KIEs (Table 3). The trend is best depicted by the series of substituted X-1 with chloroacetic acid (Figure 4). The computed change in KIE is also reasonable for the series of substituted acetic acids (Figure 5) using the parent α-methoxystyrene as the substrate, although there is a leveling effect as the acidity increases in experiments, but not from computaton.6 One possible reason for this small difference is the use of a single fractionation factor for different substituted acids derived from acetic acid to convert the experimental PIEs into KIEs.7,45 However, the computational results include the difference in fractionation factors among different acids (see below). For example, if a smaller fractionation factor is used for the weaker acids in the experimental data, the agreement with theory can be significantly improved.

Table 3.

Computed and experimental primary kinetic isotope effects (KIE), along with the KIE determined using the Bigeleisen equation with harmonic vibrational frequencies, the anharmonicity correction factor and tunneling contributions, for the protium/deuterium transfer reactions from substituted acetic acid (Y-CH2CO2H) to aryl substituted α-Methoxystyrenes (X-1) at 25°C.

| X-1 | Y-AcOH(D) | κtun | KIE(calc) | KIE (expt) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-MeO- | Cl- | 5.547 | 1.126 | 1.268 | 7.92 | 7.7 |

| H- | Cl- | 5.507 | 1.119 | 1.162 | 7.16 | 7.0 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 4.775 | 1.094 | 1.035 | 5.53 | 5.8 |

| 3,5-di-NO2- | Cl- | 3.951 | 1.093 | 1.018 | 4.40 | 4.8 |

| H- | di-Cl- | 5.532 | 1.267 | 1.237 | 8.67 | 7.0 |

| H- | NC- | 5.605 | 1.234 | 1.200 | 8.30 | 7.2 |

| H- | Cl- | 5.507 | 1.119 | 1.162 | 7.16 | 7.0 |

| H- | MeO- | 5.366 | 1.111 | 1.082 | 6.45 | 6.8 |

| H- | H- | 5.290 | 1.060 | 1.045 | 5.86 | 5.8 |

| 4-NO2- | di-Cl- | 5.414 | 1.291 | 1.106 | 7.73 | 6.7 |

| 4-NO2- | NC- | 5.260 | 1.253 | 1.059 | 6.98 | 6.0 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 4.884 | 1.094 | 1.035 | 5.53 | 5.8 |

| 4-NO2- | MeO- | 3.973 | 1.117 | 1.014 | 4.50 | 5.9 |

| 4-NO2- | H- | 3.460 | 1.039 | 1.007 | 3.62 | 5.4 |

Figure 4.

Experimental (black) and computed (red) kinetic isotope effects (KIE) for the reaction of chloroacetic acid and substituted α-methoxystyrenes (X-1). KIEs computed using the Bigeleisen equation (eq 1) are given in green. Inclusion of anharmonicity contributions increases the computed KIEs, and is shown in blue. This is followed by inclusion of tunneling contributions to yield the total computed KIEs from path integrals determined with the Kleinert second-order perturbation theory (red).

Figure 5.

Variations of the computed KIEs using the Bigeleishen equation with harmonic frequencies (green) along with the inclusion of anharmonicity (blue) and tunneling (red) for the reactions of α-methoxystyrene with various substituted acetic acids (Y-AcOH). The experimental data are depicted in black.

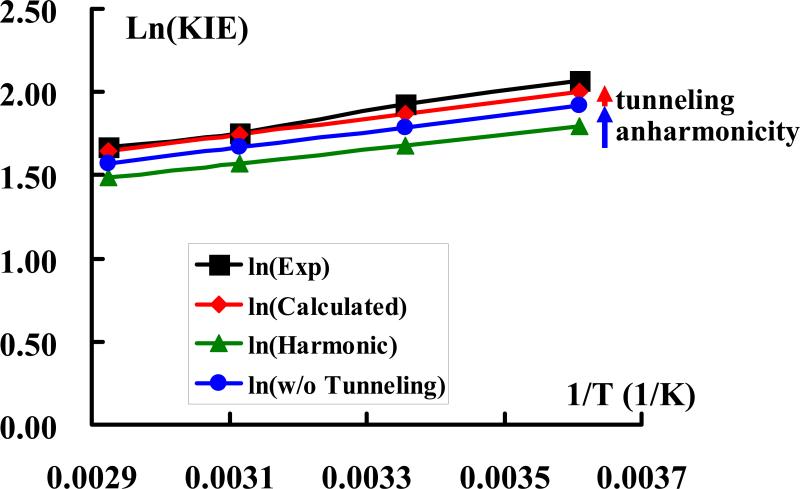

Figure 6 shows the temperature-dependence of the KIE for the reactions of α-methoxystyrene (H-1) and methoxyacetic acid computed using KP2/P20. A slope of , where R is the gas constant, and an intercept of ln(AH / AD) = 0.128 are obtained from Figure 6. Both values are in reasonable agreement with the experimental results, which are 595 ± 30 K and 0.02 ± 0.10, respectively. This yields a computed difference of kcal/mol for the protonation of H-1 by H and D, which may be compared with the experimental value of −1.18 kcal/mol. The slightly underestimated difference is reflected by a smaller calculated KIE (6.45) than that from experiments (6.8). The Y-intercept in Figure 6 gives a value of 1.14 for the ratio AH / AD, but the experimental value is closer to unity (1.02). The computed temperature dependence in the Arrehnius-type plot indicates that there is a small amount of hydrogen tunneling, but the extrapolation of the experimental temperature dependence of KIE indicates that there is little tunneling.6,7,44 Nevertheless, we note that the computed tunneling effects contributes no more than 0.1 kcal/mol to the overall thermal activation barrier of 18.4 kcal/mol (17.5 kcal/mol from experiment) for the protonation of H-1 by methoxyacetic acid, and these proton transfer reactions are dominated by over barrier processes. Figures 5 and 6 (see also Table 3) show that the computed KIEs are dominated by contributions from harmonic vibrations, whereas anharmonicity and tunneling contributions are relatively small, but they make important contributions to the calculation of the absolute KIE values.5,21

Figure 6.

Experimental (black) and computional (red) temperature dependence of KIEs for the protonation reaction of α-methoxystyrene (H-1) by methoxyacetic acid using the path integral-KP2/P20 method. Results obtained with the Bigeleisen equation using harmonic frequencies (green) and the effects of anhamonicity (blue) and tunneling (read) are also shown.

B. Factors that influence the trend of KIE

In the present integration-free path-integral method,14,15 we make use of independent normal mode coordinates in the calculations of the centroid potential of path integrals. Although this assumption neglects correlation between different normal mode coordinates, the error introduced appears to be small from previous studies14,15,18 and for the present proton transfer reactions as evidenced by the good agreement in the computed free-energy barriers and KIE values with experiments.6 Importantly, it allows us to separate the overall quantum effects into contributions from harmonic vibrations,21 anharmonicity, and quantum tunneling to provide further insight into the origin of the dependence of KIE on substituent effects, both on the substrate and the proton donor. In this analysis, the total KIE in eq 2 can be decomposed as follows:

| (4) |

where is the KIE determined using the Bigeleisen equation,11-13 eq 1, with harmonic vibrational frequencies, is the anharmonicity correction factor for the KIE from all modes with real (positive) frequencies as determined by the KP2 theory of the centroid path integrals using the exact potentials from PCM-B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) calculations, and κtun represents tunneling contributions to the computed KIE value, corresponding to the imaginary normal modes. Refs. 14, 15 and 18 contains theoretical and computational details of this decomposition analysis.

B.1. KIE determined with harmonic frequencies

The computed KIEs using the Bigeleisen equation (eq 1) for the three series of protonation reactions of X-1 and Y-AcOH(D) are shown in Table 3 and Figures 4 and 5. The overall trends of the computed “harmonic” KIEs are in accord with the corresponding experimental data;6 however, they are underestimated by more than 30% for the fast reactions and by 10-20% for the slower processes. Quantum mechanical tunneling is undoubtedly important in computing kinetic isotope effects,5,20,21 and inclusion of tunneling contributions by multiplying the tunneling factor in Table 3 significantly improves the computed KIE for the slower protonation reactions of substituted α-methoxystyrenes, reducing the errors to about 5% or less, but errors remain high for the faster reactions at nearly 20% of the experimental results. These reactions include those using very strong acids as the proton donor and electron-rich acceptors (4-MeO-1). In these cases, it is important to go beyond the Bigeleisen approach to obtain more accurate KIEs.

Figure 4 shows that the KIE determined using harmonic frequencies (green curve) decreases with increasing electron-withdrawing power of the substituent on the aryl ring. This may be attributed to the effects of charge polarization of the vinyl double bond with a reduced bond order. Consequently, there is somewhat reduced zero-point effect from the substrate X-1 in going from the reactant state to the transition state. This is consistent with the trend in Figure 5, in which the KIEs computed using harmonic frequencies are similar. Figure 5 further shows that there is little variation from harmonic frequencies with different donor acidities and this suggests that the amount of zero-point energy from the donor hydroxyl bond that is maintained in the symmetric stretch vibration is minimal.46 However, the present results do not address this issue directly, because there are other factors, such as the change in the bond order of the substrate X-1 and donor Y-AcOH.

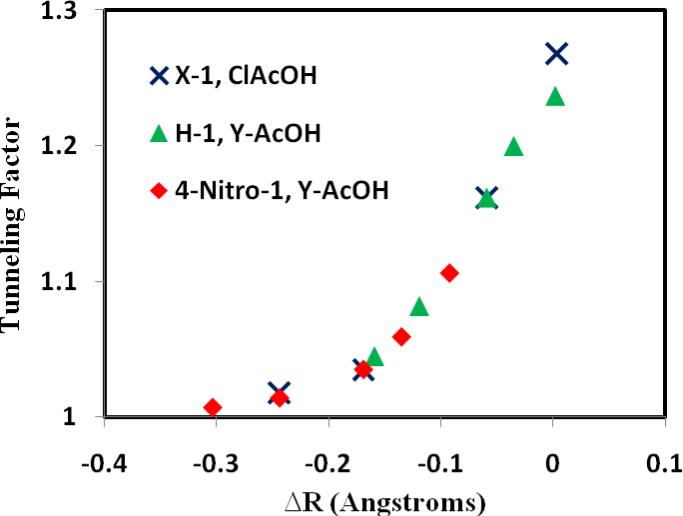

B.2. Tunneling

The quantum tunneling effect has a strong dependence on the symmetry of the donor and acceptor bond distance from the transferring proton (deuteron) at the transition state (by definition, tunneling only occurs near the transition state). Examination of Tables 2 and 3 shows that the ratio of tunneling for the H/D transfer reactions, i.e., the tunneling factor in eq 4 (κtun), has an inverse exponential correlation with the difference in bond lengths, ΔR (Figure 7). Clearly, tunneling is more important for the symmetric transition states than reactions with more asymmetric, Hammond-shifted transition structures, and it is essential to include tunneling effects for the more balanced reactions (i.e., more symmetric transition states), without which the computed KIE can be in error by more than 20%. For large (negative) values of ΔR where transition states are late along the reaction coordinate towards the product state, tunneling contributions to the computed KIE are relatively small (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Computed tunneling factors to the computed kinetic isotope effects as a function of geometrical shifts at the transition state for the reactions of α-methoxystyrene with various substituted acetic acids (Y-AcOH).

B.3. Anharmonicity

Tables 3 and 4 list the anharmonicity correction factors for the three series of reactions between substituted X-1 and substituted acetic acid (Y-AcOH) in water. The percent contribution to the total computed KIE (kH / kD) ranges from 4% for the reaction between 4-NO2-1 and AcOH(D) to 23% for the reaction between 4-NO2-1 and Cl2CHCO2H(D), whereas the anharmonicity correction factors are relatively invariant (about 10%) for the series with different substituents on X-1 but keeping the same proton donor (Cl-AcOH) (Table 3). In fact, includes anhamonic effects on the computed vibrational frequencies both at the transition state and at the reactant state. Clearly, it is useful to separate these effects to shed light on the change in anharmonic effects on the computed KIE when different acids are used (Table 4). Thus, we define

| (5) |

where and specify the isotope effects on anharmonicity in the reactant state (RS) and the transition state (TS), respectively. accounts for the isotope effects on anharmonicity of the acidity constant for exchange of H and D at the carboxylic acid, i.e., the anharmonic contributions to the factor 1/ ΦAL, which is the equilibrium constant for the exchange of H and D by the carboxylic acid in 50/50 mixture of H2O/D2O.6 It is the ratio of the Boltzmann factors for the H and D vibrational energies computed using harmonic frequencies and with the real potential energy surface that includes anharmonicity in a given acid. Thus, can be calculated by

| (6) |

where is the change in quantum energy (mostly zero-point energy and thermal contributions) due to anharmonicity at the carboxylic acid. In other words, the experimental fractionation factor defined by eq 11 in Ref. 6 is related to that computed using harmonic frequencies multiplied by , i.e., , where AL ≡ RS.6 The exchange for H and D at the TS, , may be similarly defined and can be interpreted as the anharmonic contribution to the residual zero-point energy maintained at the transition state for the transferring H and D.6

Table 4.

Computed isotope effects on anharmonicity in the reactant state and the transition state along with the total anhamonic correction factors the proton transfer reactions from substituted acetic acids to aryl-substituted α-methoxystyrenes.

| X-1 | Y-AcOH(D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-MeO- | Cl- | 0.894 | 1.007 | 1.126 |

| H- | Cl- | 0.894 | 1.000 | 1.119 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 0.894 | 0.978 | 1.094 |

| 3,5-di-NO2- | Cl- | 0.894 | 0.977 | 1.093 |

| H- | di-Cl- | 0.790 | 1.001 | 1.267 |

| H- | NC- | 0.808 | 0.998 | 1.234 |

| H- | Cl- | 0.894 | 1.000 | 1.119 |

| H- | MeO- | 0.897 | 0.996 | 1.111 |

| H- | H- | 0.929 | 0.986 | 1.060 |

| 4-NO2- | di-Cl- | 0.790 | 1.019 | 1.291 |

| 4-NO2- | NC- | 0.808 | 1.013 | 1.253 |

| 4-NO2- | Cl- | 0.894 | 0.978 | 1.094 |

| 4-NO2- | MeO- | 0.897 | 1.001 | 1.117 |

| 4-NO2- | H- | 0.929 | 0.965 | 1.039 |

Table 4 lists the total anharmonicity correction factors (Table 3) and the isotope effects on anharmonicity at the Brønsted acid and the transition state. Examining the fourth column of Table 4, we immediately notice that the isotope effects on anharmonicity are close to unity and nearly constant for the exchange of H and D at the transition state for all reactions considered. There is no clear dependence either on the substituents of X-1 or on the acidity strength of the proton donor in the small variations of a few percent (Table 3). However, there are noticeable isotope effects on anhamonicity for the exchange of H and D at the substituted carboxylic acids, with deviating from unity by 10-22% (except the parent reaction of H-1 with acetic acid). Furthermore, one can identify that the change in is closely correlated with the change in the electron-withdrawing power of the acid substituent (i.e., its acidity). This suggests that the anharmonic effect on the computed KIEs is mainly due to its modification of the H/D enrichment (ΦAH) of the Brønsted acid by using eq 1 with harmonic vibrational frequencies.

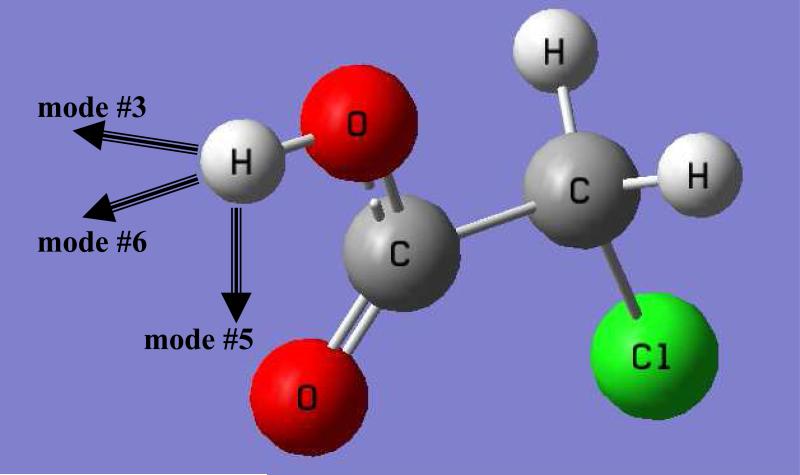

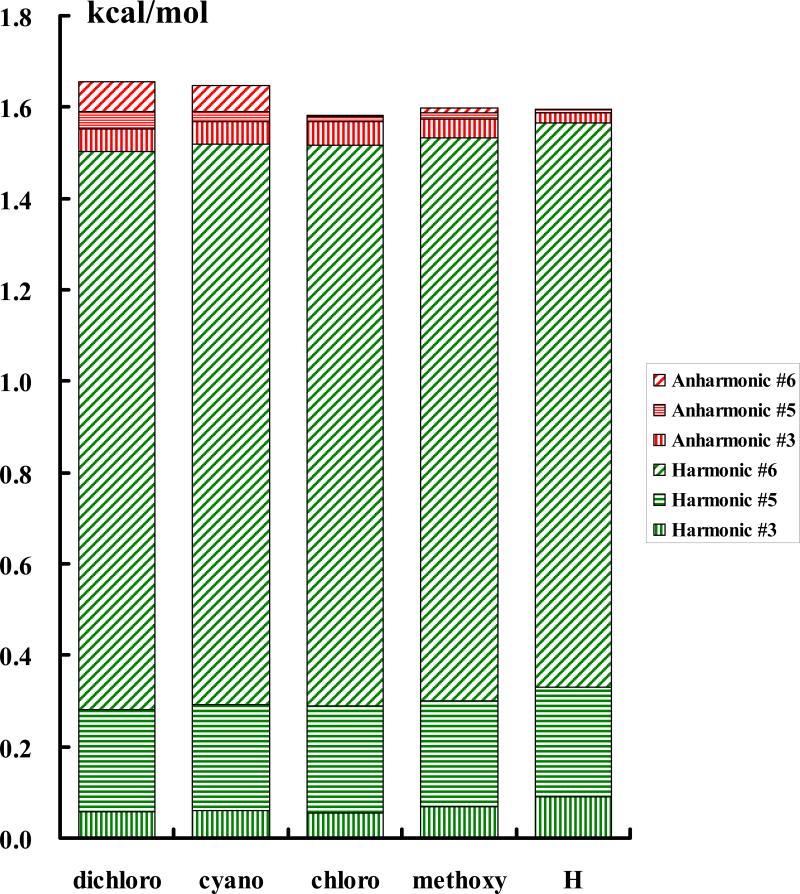

We have identified three key normal modes that have the largest anharmonic contributions (normal mode #3, #5, and #6), and they are all related to the protium/deuterium (H/D) being transferred (Figure 8). In Figure 9, we illustrate the difference in quantum mechanical effects, mostly zero-point-energy (ZPE) effects, between Y-AcO(H) and Y-AcO(D). The differences in the total quantum harmonic vibrational energy or harmonic centroid potential energy are shown in green, decomposed into the three specific modes. The corresponding anharmonic contributions are illustrated in red. The sum of harmonic and anharmonic corrections is the total quantum energy difference from the centroid potential between the two isotopic acids. The trend in Figure 9 follows the increase in donor acidity, resulting in a decrease in bond strength and force constants involving the H/D modes. This is reflected by the decreasing trend of ZPE from harmonic modes (green bars in Figure 9). However, as the force constants decrease, (the potential energy surface becomes flatter) and the deviation from the harmonic approximation becomes greater, leading to larger anharmonic contributions. This is consistent with the increasingly large anharmonic energy corrections in Figure 9 (red). This is reflected by the observation and trends of anharmonic contributions to the computed KIE in Table 4.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the three normal modes identified to have the largest anhamonic effects as electron-withdrawing substituents are introduced. All three modes are associated with the protium/deuterium as depicted by chloroacetic acid.

Figure 9.

. Differential quantum mechanical effects (mainly zero-point energy) between H and D isotopes in various substituted acetic acids for the three modes depicted in Figure 4. Zero-point energies computed using harmonic vibrational frequencies are shown in green, and anharmonicity corrections, which are relatively small, are depicted in red. Anharmonic effects from each mode are also identified.

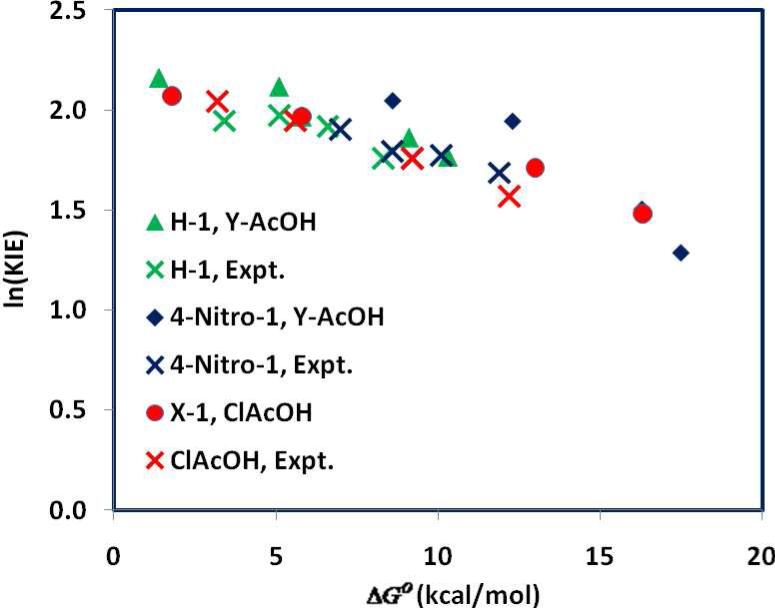

Finally, in Figure 10, we illustrate the variation in KIE as a function of the thermodynamic driving force, ΔGo. The experimental data cover a large range of 16 kcal/mol, which are compared with the computational data for the three series of different substitutions on X-1 or on Y-AcOH. The computed free energy change for the formation of the carbenium ion X-2+ are in excellent agreement in the middle range with the experimental data, but the calculated values are stretched and shows greater deviations from experiments (Table 1 and Figure 10). Although the experimental data and computational results are not exactly matched, the trends are undoubtedly similar for the change in KIE over a large range of thermodynamic driving force.

Figure 10.

The effect of thermodynamic driving force for the formation of the carbenium ion intermediate on the kinetic isotope effects (KIE) for protonation of substituted α-methoxystyrene (H-1) by chloroacetic acid (red), and H-1 (green) and 4-nitro-1 (blue) by substituted carboxylic acids Y-AcOH. Experimental data are indicated by cross marks in the same color scheme.

V. Conclusions

Primary kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) on a series of carboxylic acid-catalyzed protonation reactions of aryl-substituted α-methoxystyrenes (X-1) to form oxocarbenium ions have been computed using the Kleinert variational second-order perturbation theory (KP2) in the framework of Feynman path integrals (PI) and the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) potential surface coupled with the polarizable continuum model to represent aqueous solution. Reasonable agreement with the experimental data was obtained, demonstrating that this novel computational approach for computing KIEs of organic reactions is a viable alternative to go beyond the traditional method employing Bigeleisen equation, where anharmonicity and tunneling contributions are important. We found that the dominant factor contributing to the observed KIE for the protonation reactions of substituted α-methoxystyrenes is due to the change in zero-point energy from the reactant to the transition state, and the trend of the computed KIEs using Bigeleisen equation is in accord with experiment. However, it is necessary to include tunneling contributions to obtain quantitative estimates of the KIEs. Without tunneling, the RMSD error in the computed KIEs using Bigeleisen equation is 23% in comparison with the experimental data, and this is reduced to 15% with tunneling contributions. Consideration of anharmonicity can further improve the calculated KIEs; for example, for the protonation of substituted X-1 by a common acid, chloroacetic acid, the anharmonicity corrected KIEs are in quantitative agreement with experiment (Figure 4). On the other hand, for the reactions of α-methoxystyrene and 4-NO2-1 with substituted carboxylic acid, the correction of anharmonicity leads to overestimation of the computed KIEs for strong acid catalysts, but there is a noticeable leveling effect in the observed KIEs as the acidity increases (Figure 5).

The results for experiments and calculations are each consistent with the conclusion that proton transfer from Brønsted acids to X-1 proceeds mainly by an activation-limited reaction, where the proton passes over an energy barrier. However, extrapolation of a linear Arrhenius type relationship of the product isotope effects (PIEs) for protonation of H-1 by methoxyacetic acid to 1/T = 0 gives a limiting PIE of 1.0 at infinite temperature. This result provides no evidence for the existence of a tunneling pathway at room temperature, while the tunneling correction results in an increase in the isotope effect over that calculated for proton transfer over a reaction barrier (i.e., without tunneling), ranging from as little as 1% to as large as 26%. We conclude that either these Arrhenius type relationships are unable to detect relatively small amounts of tunneling for these room temperature proton transfer reactions, or that these calculations overestimate the required tunneling correction. In agreement with the experimental findings in the accompanying paper, the largest KIEs are found in reactions with ΔGo ≈ 0, where the transition structures are nearly symmetric and the reaction barriers are relatively low. Furthermore, we found that the optimized transition structures are strongly dependent on the free energy for the formation of the carbocation intermediate, ΔGo. The observed Hammond-shift in the position of the transition state for the protonation reactions of X-1 by substituted acetic acids leads to reduced tunneling as well as zero point energy contributions to the computed KIEs. This is consistent with the observed increase in the Brøsted parameter for these reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health under grants GM46736 (J.G.) and GM39754 (J.P.R.).

References

- 1.Wendt KU, Schulz GE, Corey EJ, Liu DR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendt KU, Poralla K, Schulz GE. Science. 1997;277:1811. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng J, Hoshino T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:1689. doi: 10.1039/b823167b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajamani R, Gao J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12768. doi: 10.1021/ja0371799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohen A, Limbach H-H. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton: 2006. p. 1074. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsang W-Y, Richard JP. accompanying paper.

- 7.Tsang W-Y, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10330. doi: 10.1021/ja073679g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinert H. Phys. Lett. A. 1993;173:332. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinert H. Path integrals in quantum mechanics, statistics, polymer physics, and financial markets. 3rd ed. World Scientific; Singapore; River Edge, NJ: 2004. p. xxvi.p. 1468. For the quantum mechanical integral equation, see Section 1.9; For the variational perturbation theory, see Chapters 3 and 5.

- 10.Feynman RP, Hibbs AR. Quantum mechanics and path integrals. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1965. p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigeleisen J. J. Chem. Phys. 1949;17:675. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigeleisen J. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:2264. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaad LJ, Bytautas L, Houk KN. Can. J. Chem. 1999;77:875. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong K-Y, Gao J. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:211103. doi: 10.1063/1.2812648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong K-Y, Gao J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:1409. doi: 10.1021/ct800109s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giachetti R, Tognetti V. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985;55:912. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feynman RP, Kleinert H. Phys. Rev. A. 1986;34:5080. doi: 10.1103/physreva.34.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong K-Y. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Minnesota (USA); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfsberg M. In: Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. Kohen A, Limbach H-H, editors. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton: 2006. pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Ramos A, Miller JA, Klippenstein SJ, Truhlar DG. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4518. doi: 10.1021/cr050205w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pu J, Gao J, Truhlar DG. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3140. doi: 10.1021/cr050308e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillan MJ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987;58:563. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao J, Voth GA. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;101:6168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voth GA. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1996;93:135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voth GA, Chandler D, Miller WH. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;91:7749. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang S, Schwieters CD, Voth GA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1999;103:9527. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jang S, Voth GA. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;112:8747–8757. Erratum: 2001, 114, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao J, Wong K-Y, Major DT. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:514. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Lu Z, Yang W. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:124516. doi: 10.1063/1.2181145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Hammes-Schiffer S. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:184102. doi: 10.1063/1.2362823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miertus S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J. Chem. Phys. 1981;55:117. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cammi R, Tomasi J. J. Comput. Chem. 1995;16:1449. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui K. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981;14:363. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulsen JA, Nyman G, Rossky PJ. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006;2:1482. doi: 10.1021/ct600167s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1372. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11623. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr., Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barone V, Cossi M, Tomasi J. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;107:3210. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takano Y, Houk KN. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:71. doi: 10.1021/ct049977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiberg KB. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:1083–96. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glendening ED, Weinhold F. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:610–627. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glendening ED, Badenhoop JK, Weinhold F. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:628. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richard JP, Williams KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6952. doi: 10.1021/ja071007k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarret RM, Saunders M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:2648. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westheimer FH. Chem. Rev. 1961;61:265–273. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.