Abstract

The present study examines the effect of reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) column diameter (1 mm to 9.4 mm I.D.) on the one-step slow gradient preparative purification of a 26-residue synthetic antimicrobial peptide. When taken together, the semi-preparative column (9.4 mm I.D.) provided the highest yields of purified product (an average of 90.7% recovery from hydrophilic and hydrophobic impurities) over a wide range of sample load (0.75–200 mg). Columns with smaller diameters, such as narrowbore columns (150 × 2.1 mm I.D.) and microbore columns (150 × 1.0 mm I.D.), can be employed to purify peptides with reasonable recovery of purified product but the range of the crude peptide that can be applied to the column is limited. In addition, the smaller diameter columns require more extensive fraction analysis to locate the fractions of pure product than the larger diameter column with the same load. Our results show the excellent potential of the one-step slow gradient preparative protocol as a universal method for purification of synthetic peptides.

Keywords: Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, Preparative chromatography, Antimicrobial peptide

1. Introduction

The growing therapeutic importance of antimicrobial peptides in recent years has led to a concomitant increase in the need for rapid and efficient peptide purification procedures. To obtain antimicrobial peptides, peptide synthesis is the favored method especially for de novo antimicrobial peptide design. The impurities created during peptide synthesis are usually closely related structurally to the peptide of interest and hence often pose difficult purification problems. The excellent resolving power of reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) has made it the predominant high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) technique for preparative peptide separations [1–4]. Indeed, not only is RP-HPLC usually superior to other modes of HPLC with respect to both speed and efficiency, but it also offers the widest scope for manipulation of mobile phase conditions and choices of different columns to optimize separations. Also, most researchers would likely wish to carry out both analytical and preparative peptide separations on analytical equipment with columns no longer than 250 mm and no larger than 10 mm internal diameter (I.D.), thus, avoiding prohibitively expensive scale-up costs in terms of equipment, larger columns and solvent consumption. An ongoing commitment of this laboratory is the development of one-step RP-HPLC purification procedures to avoid the loss of product yield, which is frequently a feature of multi-step protocols.

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated the value of slow acetonitrile gradients (0.1–0.2% CH3CN/min) for peptide separations compared to the more traditionally employed conditions of 0.5–1% CH3CN/min, allowing excellent levels of product purity and yield from widely varying sample loads [1,5,6]. In the present study, we describe the application of a one-step preparative RP-HPLC protocol employing slow acetonitrile gradients to the purification of an amphipathic, α-helical antimicrobial peptide on reversed-phase columns of varying column diameters (1 mm to 9.4 mm I.D.). Our objectives were two-fold: first, to examine the effect of column diameter on product purity and yield during one-step preparative purification of the antimicrobial peptide; second, to examine the potential of this slow gradient protocol as a general method for purifying peptides with closely-related impurities from a wide range of sample loads.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

t-Boc-protected (tert-butyloxycarbonyl) amino acids were purchased from Advanced ChemTech (Louisville, KY, USA). o-Benzotriazol-1-yl-N,N,N,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and 4-methylbenzhydrylamine resin hydrochloride salt (MBHA) (100–200 mesh) were obtained from Advanced ChemTech. Anisole and 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) were supplied by Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dimethylformamide (DMF) was obtained from FisherBiotech (Fairlawn, NJ, USA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was obtained from Hydrocarbon Products (River Edge, NJ, USA) and diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). De-ionized water was purified by an E-pure water filtration device from Barnstead/Thermolyne (Dubuque, IA, USA).

2.2. Peptide synthesis and purification

Synthesis of the peptide Ac-KWKSFLKTFKSAKKTVLH-TALKAISS-amide with all D-amino acids was carried out by solid-phase peptide synthesis using t-butyloxycarbonyl chemistry on MBHA (4-methylbenzhydrylamine) resin (0.97 mmol/g), as described previously [7]. The Boc-groups were removed at each cycle with 50% (v/v) TFA/dichloromethane. Coupling of the amino acids was achieved at each cycle by 5 min activation with HBTU/HOBt/DIEA/DMF, followed by shaking with the resin for 30 min. Finally, at the completion of the synthesis, the peptides were acetylated with 10% acetic anhydride/20% DIEA/70% dichloromethane (v/v/v). The peptide was cleaved from the resin by treatment with HF (30 ml/g resin) containing 10% anisole and 2% 1,2-ethanedithiol at −5 °C to 0 °C for 1 h. The cleaved peptide-resin mixture was washed with diethyl ether (3 ml × 25 ml) and the peptide extracted with 50% aq. acetonitrile (3 ml × 25 ml). The resulting peptide solution was then lyophilized prior to purification.

2.3. Instrumentation

Two HPLC instruments were employed: (1) a Beckman Coulter System Gold Preparative HPLC system, coupled with System Gold 126 solvent module, System Gold 168 detector with standard flow cell (path length 10 mm and volume 17 μl) and 32 Karat chromatography software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA); and (2) an Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) with diode array and multiple wavelength detector (standard flow cell, path length 10 mm and volume 13 μl).

The correct masses of the peptides were confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry using a Mariner Biospectrometry Workstation mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA, USA).

Amino acid analysis of the purified peptide was carried out on a Beckman Model 6300 amino acid analyzer.

2.4. Columns and HPLC conditions

Four different reversed-phase columns were used to purify the crude peptide in this study: (1) a semi-preparative Zorbax 300SB-C8 column (250 × 9.4 mm I.D.; 6.5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size); (2) an analytical Zorbax 300SB-C 8 column (150 × 4.6 mm I.D.; 5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size); (3) a narrowbore Zorbax 300 SB-C8 column (150 × 2.1 mm I.D.; 5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size); and (4) a microbore Zorbax 300 SB-C8 column (150 × 1.0 mm I.D.; 3.5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size). All four columns were purchased from Agilent Technologies.

All preparative runs were carried out with a linear AB gradient (1% acetonitrile/min for 30 min up to 30% acetonitrile, followed by 0.1% acetonitrile/min for 250 min up to 55% acetonitrile) at room temperature and a flow-rate of 2 ml/min, 1 ml/min, 0.25 ml/min or 0.08 ml/min for the semi-preparative column, analytical column, narrowbore column and microbore column, respectively, where eluent A was 0.2% aq. trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) pH 2 and B was 0.2% TFA in acetonitrile. Chen et al. had previously demonstrated that 0.2–0.25% TFA in the mobile phase achieved optimum resolution of peptide mixtures compared to the 0.05–0.1% TFA concentrations traditionally employed [8]. Following the slow gradient step, the column was washed with 70% acetonitrile for 30 min. The semi-preparative column was used on the Beckman Coulter System Gold instrument for purification of 100 mg and 200 mg sample loads. All other sample loads for the semi-preparative column and the other columns were carried out on the Agilent instrument.

Crude peptide was dissolved in 0.2% aq. TFA at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. All samples were loaded at the same flow-rate as the flow-rate used for column elution. For the semi-preparative column, multiple injections through a 5 ml injection loop were carried out on the Beckman instrument; for the analytical column, multiple injections through a 900 μl injection loop in the auto-sampler were carried out on an Agilent 1100 instrument.

Analytical RP-HPLC was carried out on the Zorbax 300 SB-C8 narrowbore column with a linear AB gradient (1% acetonitrile/min) at a flow-rate of 0.25 ml/min, where eluent A was 0.2% aq. TFA, pH 2, and eluent B was 0.2% TFA in acetonitrile.

2.5. Product collection and calculation of product recovery

For all preparative runs, 0.5 min fractions were collected by a Foxy Jr. fraction collector (Isco Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). Two different lines were used between the detector and the fraction collector in order to minimize the dispersion volume. A line 49 in. in length was used for the runs on semi-preparative and analytical columns (0.02 in. I.D. and 252 μl hold-up volume); in contrast, the line used for the runs on narrowbore and microbore columns, though of the same length, had an I.D. of just 0.01 inch and a subsequent hold-up volume of only 63 μl. The use of standard fraction collector lines of 0.04 in. I.D. and line volumes of 1 ml or greater depending on the line length have little effect on sample dispersion after the detector for flow-rates greater than 1 ml/min. However, when using a flow-rate of 0.25 ml/min for the narrowbore column and 0.08 ml/min for the microbore column, the use of standard collector lines (e.g., 0.04 in. I.D.) will have dramatic effects on band overlap after the sample leaves the detector. For example, this can reduce the yields of pure product recovery from 78% on the microbore column (with a load of 3 mg crude) with the 0.01 in. I.D. line (Table 1) to 34% recovery with the 0.04 in. I.D. collection line. Thus, it is extremely important to use lines with the I.D.s denoted in the manuscript. Fractions were screened by mass spectrometry and checked by analytical RP-HPLC to identify fractions containing product. Fractions were combined into three pools containing hydrophilic impurities, pure product and hydrophobic impurities. These three pools were lyophilized and re-dissolved in 0.2% aq. TFA. The volume of 0.2% aq. TFA used for redissolving the lyophilized peptides was determined by the volume required to dissolve the initial amount of crude peptide loaded onto the column for a final concentration of 10 mg/ml, e.g., for the purification of 200 mg crude peptide, the three pools were each dissolved in 20 ml of 0.2% aq. TFA. Aliquots (5 μl) of pooled solutions were injected onto the Zorbax 300SB-C8 narrowbore column for analytical RP-HPLC analysis. For 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg sample loads, the three pools containing hydrophilic impurities, pure product and hydrophobic impurities were each dissolved in 0.6 ml from which 20 μl and 40 μl of the pooled solutions were injected for analysis of recovery, respectively. Product recovery was calculated (based on integrated peak areas) as the percentage of pure product recovered from the total product eluted from the column.

Table 1.

Load and recovery of purified product during preparative RP-HPLC of crude D-V13KD

| HPLC column | Column diameter (mm) | Column length (mm) | Peptide loaded (mg) | Product recovery (%)a | Product recovered (mg)b | Product recovered μmol)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-prep. column | 9.4 | 250 | 200.0 | 90.4 | 66.0 | 22.1 |

| 100.0 | 87.5 | 31.9 | 10.7 | |||

| 6.0 | 90.3 | 2.0 | 0.7 | |||

| 1.5 | 92.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |||

| 0.75 | 92.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||

| Analytical column | 4.6 | 150 | 28.0 | 87.0 | 8.9 | 3.0 |

| 1.5 | 89.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |||

| Narrowbore column | 2.1 | 150 | 6.0 | 82.1 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| 1.5 | 86.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |||

| Microbore column | 1.0 | 150 | 3.0 | 78.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| 1.5 | 88.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |||

| 0.75 | 90.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

Recovery (%) is calculated as the amount of pure product recovered as a percentage of total product eluted from the column.

Product recovered in milligrams was determined by the equation: product recovered (mg) = crude peptide loaded (mg) × 36.5% × product recovery (%). The peptide product is 36.5% of the crude peptide.

Product recovered in micromole was determined as product recovered in milligram × 1000 divided by the molecular weight of peptide D-V13KD (2990.6).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Antimicrobial peptide used in this study

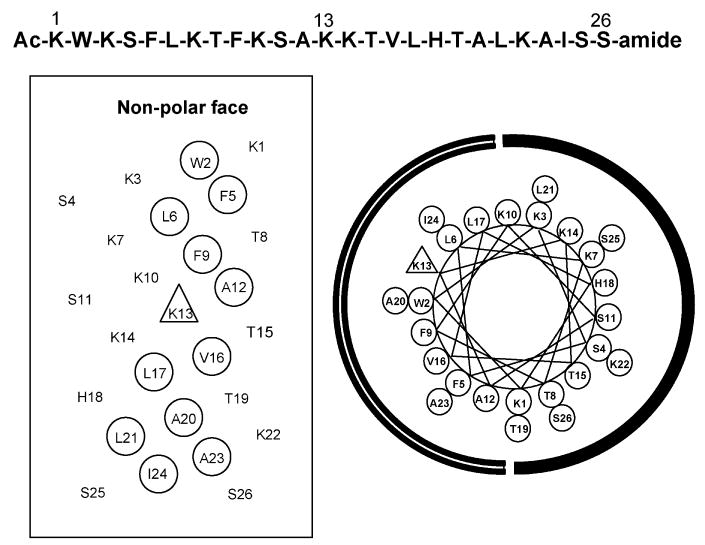

In a previous study [7], peptide D-V13KD, with a sequence of Ac-KWKSFLKTFKSAKKTVLHTALKAISS-amide (Fig. 1), was demonstrated to have negligible hemolytic activity against human red blood cells coupled with strong antimicrobial activity and hence, high therapeutic potential for clinical practice. As shown in Fig. 1, peptide D-V13KD is an amphipathic α-helical peptide with a polar face (comprised of hydrophilic Lys, Ser, Thr and His residues) and a non-polar face, comprised almost completely of non-polar residues (Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Phe, Trp), the only exception being the presence of a hydrophilic lysine residue in the centre of the non-polar face (position 13). The central location of the Lys residue has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in producing the high therapeutic index of the peptide [7,9].

Fig. 1.

Sequence of peptide D-V13KD (top) and representation as a helical net (left) and helical wheel (right). In the helical net, non-polar residues making up the non-polar face of the amphipathic peptide are circled. In the helical wheel, the non-polar face of the amphipathic peptide is indicated by an open arc, whilst the polar face is indicated by a solid arc. The lysine residue at position 13 of the sequence is denoted by a triangle on the non-polar face of both representations. Ac denotes Nα-acetyl and amide denotes Cα-amide. One-letter codes are used for the amino acid residues.

Although peptide D-V13KD is completely composed of D-amino acids, it exhibited a circular dichroism spectrum that was the exact mirror image of its L-enantiomer, with equivalent ellipticity but of opposite sign in the presence of 50% aq. trifluoroethanol (TFE) [7], a helix-inducing solvent [10–13]. It is well known that characteristic RP-HPLC conditions (hydrophobic stationary phase, non-polar eluting solvent) induce helical structure in potentially helical polypeptides [14–16]. When induced by the hydrophobic stationary phase into an amphipathic α-helix, D-V13KD will exhibit preferential binding of its non-polar face to the stationary phase. Zhou et al. [14] demonstrated that, because of such a preferred binding domain, amphipathic α-helical peptides are considerably more retentive than non-amphipathic peptides of the same amino acid composition.

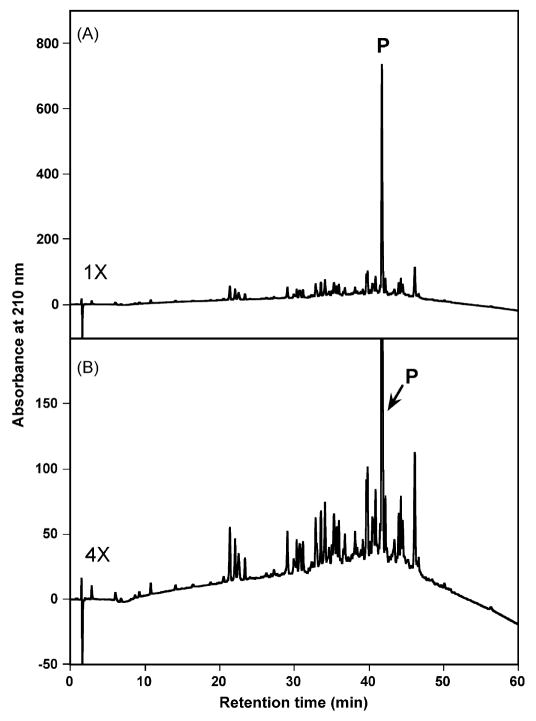

3.2. Analytical RP-HPLC of crude peptide

The synthesis of the peptide by the solid-phase approach was successful; however, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic impurities are present in the crude peptide mixture, a number of which are eluted close to the peptide of interest, thus, offering a good test for a one-step preparative RP-HPLC purification protocol (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 shows the analytical elution profile of crude peptide D-V13KD at pH 2. The large peak, denoted P, is the desired peptide component, representing 36.5% of the total components in the chromatogram as determined by peak area (impurities plus product).

Fig. 2.

Analytical RP-HPLC profile of the crude peptide. Column: narrowbore Zorbax 300SB-C8 column (150 × 2.1 mm ID; 5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size). Conditions: linear AB gradient (1% acetonitrile/min) at a flow-rate of 0.25 ml/min at room temperature, where eluent A is 0.2% aq. TFA and eluent B is 0.2% TFA in acetonitrile. Panel B represents a four-fold magnification of Panel A. P denotes the desired product.

3.3. Purification protocol

In order to design a slow gradient preparative protocol, it is first necessary to determine the concentration of acetonitrile required to elute the peptide of interest during an initial analytical run. In the present study, D-V13KD was subjected to an analytical run on the narrowbore column at a gradient rate of 1% CH3CN/min, when it was eluted at a retention time equivalent to a concentration of 42% CH3CN. To establish the percentage CH3CN at which the 0.1% CH3CN/min slow gradient should begin, our rule of thumb was to start at an acetonitrile concentration 12% below that required to elute the peptide in the 1% acetonitrile/min analytical run. Thus, the conditions for the current preparative run was an initial 1% acetonitrile/min gradient up to 30% acetonitrile (30% is 12% below 42%), followed by a slow gradient of 0.1%/min for 250 min (an increase of 25% CH3CN for a final acetonitrile concentration of 55%). Finally, an isocratic column wash step with 70% acetonitrile for 30 min eluted any remaining hydrophobic impurities off the column.

A key advantage of such a slow gradient approach is that, at high sample loads, sample displacement can occur where the hydrophobic impurities displace the product of interest and the product of interest displaces the hydrophilic impurities during partitioning of product and impurities, thus, aiding in the separation of product from closely adjacent impurities [17–20]. In addition, the desired product may be eluted over a number of fractions, the bulk of which would contain purified product only, with just the first and last product fractions containing hydrophilic and hydrophobic impurities, respectively, leading to improved resolution and yield of the product of interest. The above “rule of thumb” approach whereby the shallow gradient is started 12% below the acetonitrile concentration required to elute the peptide of interest in an analytical run is generally applicable to polypeptides of 10 residues in length and longer due to the mechanism of multisite binding of peptides to the hydrophobic matrix [21] (as opposed to the partitioning mechanism of small organic molecules [5]) preventing their elution until the acetonitrile concentration approaches that required to elute them during an analytical run. Indeed, peptides exhibit narrow partitioning windows compared to small organic molecules [5] and such windows become narrower with increasing polypeptide chain length [21].

3.4. Column packing selection

Although the present study involves preparative peptide purification, it is also our intent to make the purification protocol generally applicable to polypeptides in general. Thus, although silica-based supports covalently linked with C4, C8 or C18 functionalities have all been employed for peptide separations [1–4], the C8 packing is perhaps the optimum choice for researchers involved with purification of both peptides and proteins [1–4,8,9,22–24] due to its intermediate retention ability [1]. All the reversed-phase columns used in the present study contain essentially identical packings, i.e., SB300-C8 stationary phase (where “SB” denotes “stablebond” material with excellent thermal and chemical stability at low pH [25–27]) with 300 Å pore size; the sole difference between the packings is the 3.5 μm particle size of the microbore column (1 mm I.D.) compared to the 5 μm particle size for the narrowbore (2.1 mm I.D.) and the ananlytical (4.6 mm I.D.) and 6.5 μm particle size for the semi-preparative column (9.4 mm I.D.). Note that the relatively small particle size of this packing (3.5–6.5 μm) also favors superior solute resolution over that of larger particle size materials characteristic of many preparative applications [6,28,29]. In addition, a pore size of 300 Å is also recognized as a good compromise when purchasing reversed-phase materials for separations of both peptides and proteins [30,31].

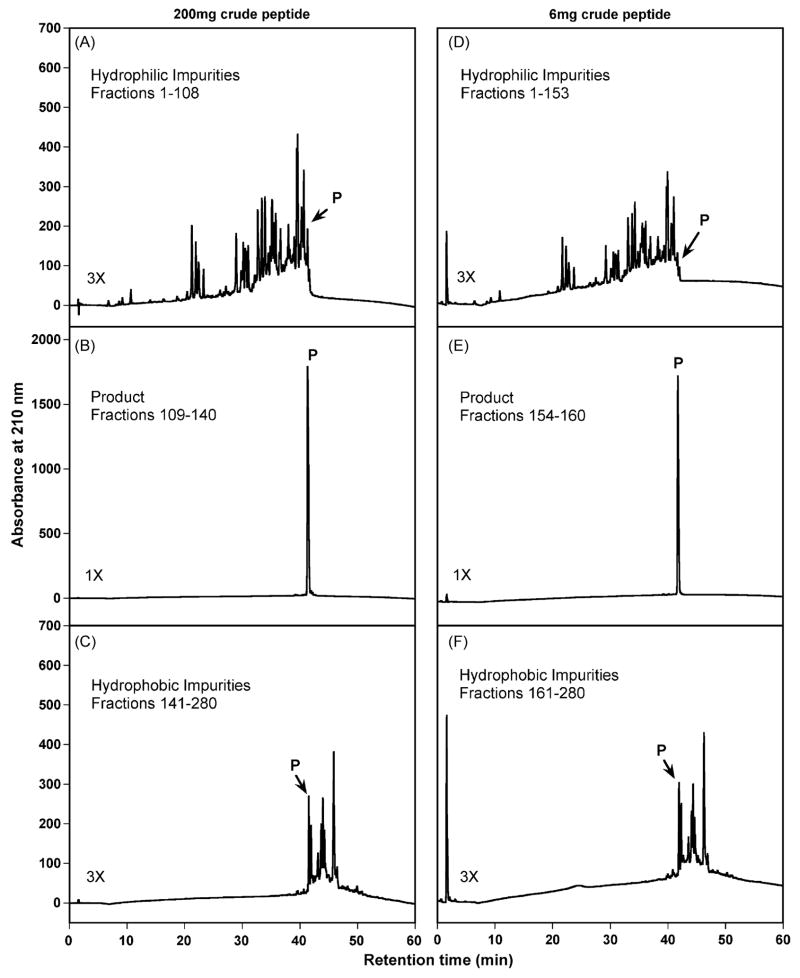

3.5. Purification of D-V13KD on a semi-preparative column (9.4 mm I.D.)

Fig. 3 shows one-step RP-HPLC purification of 200 mg (panels A–C) and 6 mg (panels D–F) of the crude peptide on the semi-preparative column. Fractions were screened by mass spectrometry and checked by analytical RP-HPLC for the fractions containing product. Fractions that contained hydrophilic impurities, pure product and hydrophobic impurities were subsequently pooled. These three pools were then lyophilized, redissolved in 0.2% aq. TFA (see Section 2 for details) and reanalyzed by analytical RP-HPLC with 5 μl sample injection volumes.

Fig. 3.

Analytical RP-HPLC profiles of the pooled hydrophilic impurities, product and hydrophobic impurities following purification on a semi-preparative reversed-phase column. Column and conditions: same as Fig. 2. Panels A, B and C show analytical profiles of the pooled hydrophilic impurities, product and hydrophobic impurities, respectively, obtained following purification of a 200 mg sample load of crude peptide dissolved in 20 ml 0.2% aq. TFA. Panels D, E and F show analytical profiles of the pooled hydrophilic impurities, product and hydrophobic impurities, respectively, obtained following purification of a 6 mg sample load of crude peptide dissolved in 0.6 ml 0.2% aq. TFA. Panels A, C, D and F represent three-fold magnifications compared to panels B and E. P denotes the desired product.

Five sample loads (200 mg, 100 mg, 6 mg, 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg) were applied to the semi-preparative column in order to investigate column performance with varying sample loads. In addition, the 0.75 mg sample load was utilized to examine the potential usage of semi-preparative column to cover peptide purification over a wide range of sample amounts. Fig. 3 demonstrates the excellent product purity (>99%) and yield obtained by this slow gradient approach to purification of the 200 mg sample load (Fig. 3B). Very little product is found either in the pooled hydrophilic fractions (Fig. 3A) or the pooled hydrophobic fractions (Fig. 3C). From Table 1, a 90.4% product recovery (66.0 mg pure product) was achieved following purification of the 200 mg sample load. A comparable result was also obtained with the 100 mg sample load on the semi-preparative column, including an 87.5% recovery of purified product (31.9 mg pure product) (Table 1). In Fig. 3 (panels D–F), it is interesting to note that excellent purity (>99%) and recovery of purified product (90.3%, Table 1) was achieved during purification of just 6 mg of sample on the semi-preparative column (9.4 mm I.D.). Recoveries of 92.7% and 92.8% of purified product were also achieved during purifications of 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg of sample on the semi-preparative column (Table 1). Thus, these results demonstrate that the semi-preparative reversed-phase column exhibits excellent column performance over a wide range of sample load (0.75–200 mg in the present study). It should be noted that the semi-preparative column is the column of choice for laboratory-scale preparative tasks to obtain peptide product from 22.1 μmol to 0.1 μmol (i.e., 66.0–0.3 mg of pure peptide product in this study; Table 1). While the semi-preparative column has the capacity for an even larger sample load than 200 mg, a shortage of crude peptide precluded our ability to determine maximum column load while maintaining satisfactory purification and yield of D-V13KD.

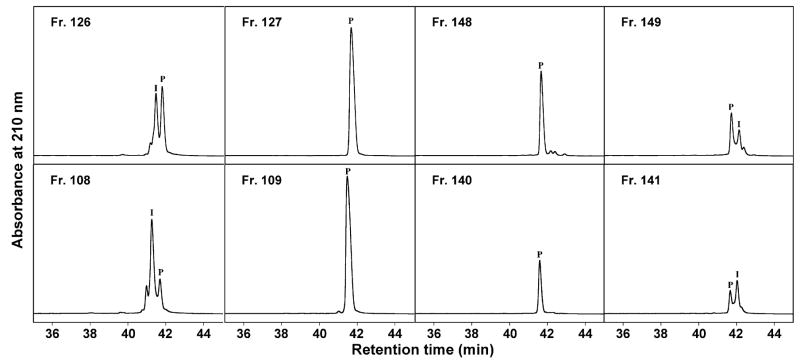

Fig. 4 illustrates fraction analyses of adjacent fractions at the beginning and end of product appearance for both the 100 mg (top panels) and 200 mg (bottom panels) sample loads. Note that only one fraction for each sample load contained overlapping product and hydrophilic impurities of any significance (Fr. 126 and Fr. 108 for 100 mg and 200 mg runs, respectively) or overlapping product and hydrophobic impurities (Fr. 149 and Fr. 141 for 100 mg and 200 mg runs, respectively), underlying the effectiveness of this slow gradient approach for resolution of desired peptide product from even closely structurally related synthetic impurities. From Fig. 4, the effect of sample load on product appearance is also apparent, i.e., the higher the sample load, the earlier the appearance of desired peptide product eluted from the column. Thus, Fractions 109, 127 and 154 were the first fractions containing the purified peptide of interest for the 200 mg load, the 100 mg load and the 6 mg load, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, the larger the sample load, the greater the number of fractions needed for product elution. Thus, 32 fractions contained the purified product for the 200 mg load, 22 fractions for the 100 mg load and 7 fractions for the 6 mg load. However, for extremely low sample loads such as 6 mg, 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg, the initial appearance of peptide product eluted from the column and the number of fractions needed for product elution were similar. Thus, fractions 154, 154 and 153 were the first fractions containing the purified peptide of interest for the 6 mg, 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg loads, respectively. Meanwhile, 7 fractions contained the purified product for the 6 mg load, 8 fractions for the 1.5 mg load and 9 fractions for the 0.75 mg load, demonstrating that 7–9 fractions are the minimum fraction numbers to collect the desired peptide product during the slow gradient preparative protocol in this study.

Fig. 4.

Analytical RP-HPLC of fractions obtained during purification of 100 mg (top) and 200 mg (bottom) of crude peptide. Column and conditions: same as Fig. 2. P denotes the desired product and I denotes impurities.

3.6. Purification of D-V13KD on an analytical column (4.6 mm I.D.)

Sample loads of 28 mg and 1.5 mg were applied to the analytical column. The higher 28 mg load of crude peptide was determined by the ratio of analytical column volume to that of the semi-preparative column. Thus, the column volume of the semi-preparative column is about 7-fold of that of the analytical column and the 28 mg sample load is essentially one-seventh of the 200 mg sample load. From Table 1, very good recoveries of 87.0% and 89.2% were achieved for the purification of 28 mg and 1.5 mg of crude peptide, respectively, recoveries, which are comparable to those, obtained following peptide purification of a wide range of sample loads on the semi-preparative column. In addition, in a similar manner to the semi-preparative separations, only one fraction for each sample load contained significant levels of overlapping product and hydrophilic impurities or overlapping product and hydrophobic impurities (data not shown).

3.7. Purification of D-V13KD on a narrowbore column (2.1 mm I.D.)

It appeared reasonable to assume that, under circumstances where only limited amounts of sample are available or only small amounts of purified material are required, columns of smaller I.D. (i.e., <4.6 mm) may be sufficient for effective peptide purification. Thus, crude D-V13KD was now applied to a narrowbore column. Based on comparison with the column volume of the semi-preparative column and its 200 mg sample load, 6 mg of crude peptide was determined as the higher end sample load for the narrowbore column. A 1.5 mg sample load was also applied for a direct comparison with the analytical column at this sample level. With the application of small diameter tubing between the detector and collector to minimize diffusion, good recovery (82.1%, Table 1) was achieved on the run with a 6 mg sample load. In addition, unlike any of the runs reported in Table 1 for the semi-preparative and analytical columns, several fractions contained overlapping product and hydrophilic impurities or overlapping product and hydrophobic impurities following this narrowbore column run. Although higher recovery (86.2%, Table 1) was achieved by reducing the sample load to 1.5 mg, clearly this is still lower than the 92.7% and 89.2% recoveries obtained for this sample load on the semi-preparative column and analytical column, respectively (Table 1).

3.8. Purification of D-V13KD on a microbore column (1 mm I.D.)

Finally, we applied a microbore column to the purification of an even smaller sample load range than the narrowbore column. A sample load of 1.5 mg of crude peptide was determined as equivalent to the 200 mg sample load on the semi-preparative column. In addition, this afforded a direct comparison with this sample load on both the analytical and narrowbore columns. A higher sample load of 3.0 mg and a lower sample load of 0.75 mg (two-fold higher and two-fold lower than the initial 1.5 mg loading) were also applied to this column. From Table 1, product recovery from the three runs was 78.0%, 88.1% and 90.2% for the 3.0 mg, 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg loads, respectively. The results suggest that the microbore column has a very narrow range of sample load for good recoveries of pure product (1.5 mg or less).

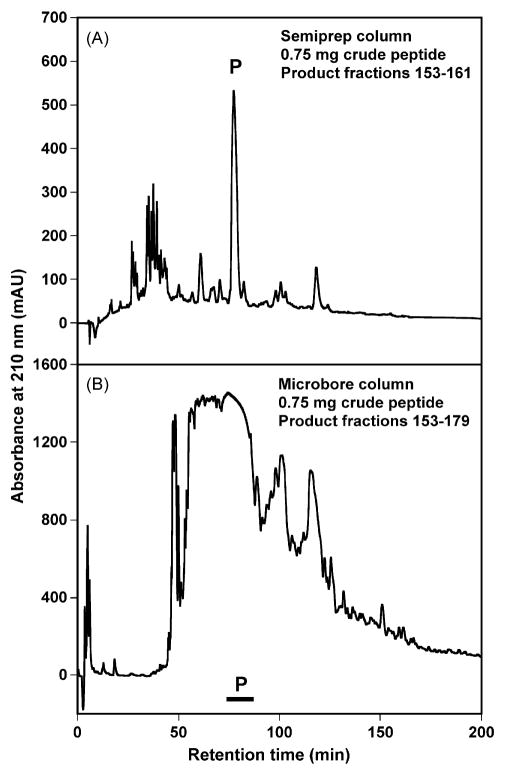

3.9. Comparison of preparative runs on the semi-preparative column and the microbore column with a sample load of 0.75 mg crude peptide

Fig. 5 compares the preparative RP-HPLC profiles on the semi-preparative column and the microbore column with a sample load of 0.75 mg crude peptide. It is obvious that the resolution of separation of the desired product is better on the semi-preparative column than on the microbore column, although the recovery rates of peptide product are comparable, i.e., 92.8% for the semi-preparative column and 90.2% for the microbore column (Table 1). In Fig. 5, it is worth noting that due to the slow flow-rate (80 μl/min) on the microbore column, the increased sensitivity of detection results in the off-scale elution profile in the preparative run in Fig. 5B. The location of the product is easily observed in the semi-preparative elution profile compared to the microbore column, which required extensive fraction analysis by mass spectrometry and analytical RP-HPLC. Hence, the semi-preparative column is superior to the microbore column in the overall ease of operation with extremely low sample loads. Due to the smaller column capacity and smaller flow-rate, peptide product was eluted from the microbore column over 27 fractions compared to only 9 fractions for the semi-preparative column.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the preparative RP-HPLC profiles of 0.75 mg crude peptide on semi-preparative (Panel A) and microbore (Panel B) columns. In Panel B, fraction containing pure product is denoted as a black bar. Product fraction numbers indicate 0.5 min per fraction.

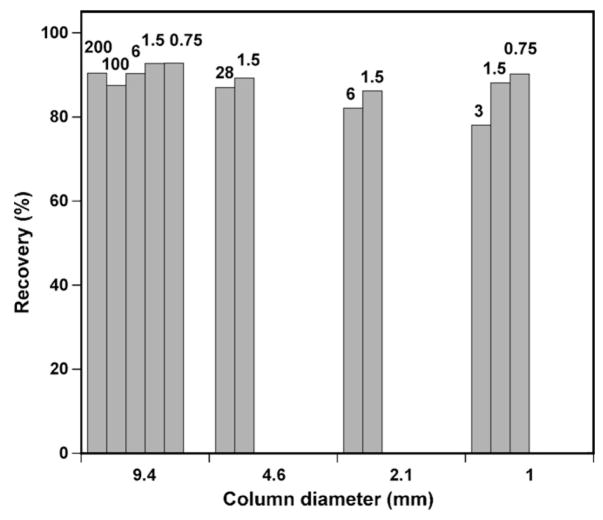

3.10. Comparison of sample recovery of D-V13KD on columns of varying diameters

Fig. 6 compares the recovery of purified D-V13KD following all the preparative runs on columns of varying diameters carried out in this study. Clearly, the most consistently high recoveries of purified product were achieved on the semi-preparative column, with an average of 90.7% recovery of purified D-V13KD over a wide range of sample load (encompassing 0.75–200 mg for the column). In contrast, preparative runs on the analytical, narrowbore and microbore columns produced generally slightly lower recoveries of purified peptide at the sample loads shown. Such results suggest that column diameter is a crucial parameter for efficient preparative separations, since all four columns used in the present study contain, for all practical purposes, identical stationary phases. From Fig. 6, it is interesting to note that, within the sample load range employed on the microbore column, recovery of purified product shows an essentially linear relationship with sample load, i.e., the greater the sample load, the lower the product recovery. The analytical column and the narrowbore column exhibit similar trends for the two sample loads employed. In contrast, such results were not observed for the runs on the semi-preparative column at any of the sample loads applied.

Fig. 6.

Recovery of purified product obtained following purification of varying amounts of crude peptide on columns with different diameters. Sample loads are indicated at the top of each plot. Data obtained from Table 1.

It should be noted that the largest column employed in the present study (9.4 mm I.D.) provided the widest choice of sample load concomitant with consistently high yields of purified product compared to smaller column diameters (Table 1). In addition, where large amounts of purified peptide are not required for further analysis, the one-step protocol on the semi-preparative column for <1 mg of pure material is also sufficient. Although consuming more solvent, carrying out purifications on the semi-preparative column is not generally an issue at this scale due to the savings in time and effort on fraction analysis using mass spectrometry and analytical RP-HPLC; in contrast, columns with smaller diameters (narrowbore column and microbore column) can be considered as preparative tools when solvent consumption is a concern.

A final observation should be made concerning the efficacy of the narrowbore column for preparative separations. Recent work in our laboratory succeeded in applying our one-step slow gradient protocol to the purification of a recombinant protein (114 amino acid residues) from 42 mg of lyophilized crude cell extract on a narrowbore column identical to that used in the present study; 4.2 mg of purified product was obtained at >94% purity [32]. Such a result is a significant improvement over that obtained with any of the peptide sample loads applied in the present study to the narrowbore column. The explanation for these differing results possibly lies in the greater potential for multisite binding of the 114-residue protein to the hydrophobic stationary phase than even the 26-residue peptide of the present study, i.e., an even narrower partitioning window for the former compared to the latter and, hence, an even smaller tendency for early partitioning of the larger polypeptide at high sample loads as the acetonitrile concentration to elute it is approached. This slower partitioning rate of large polypeptides or proteins provides an improved resolution compared to shorter peptides with wider partitioning windows and higher partitioning rates. Thus, the optimum load range on the narrowbore column (or, indeed, any column size) may vary depending on the size of the polypeptide of interest. It should be noted, however, that this variability is likely only of significance, when comparing polypeptides differing widely in size, with the results of the present study being certainly applicable to peptides generally.

4. Conclusions

The present study examined the effect of column diameter (9.4 mm, 4.6 mm, 2.1 mm and 1 mm I.D.) on a one-step slow gradient RP-HPLC protocol for preparative purification of a 26-residue antimicrobial peptide. Interestingly, the largest column (9.6 mm I.D.) provided the highest yields of purified product from the widest range of sample loads investigated (0.75–200 mg). Smaller columns remain useful as preparative tools to minimize the solvent consumption. We believe this straightforward one-step slow gradient protocol shows excellent potential as a universal method for purification of synthetic peptides with closely structurally related impurities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH grant (RO1 GM61855) to R.S.H.

References

- 1.Mant CT, Hodges RS, editors. HPLC of Peptides and Proteins: Separation, Analysis and Conformation. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mant CT, Kondejewski LH, Cachia PJ, Monera OD, Hodges RS. Methods Enzymol. 1997;289:426. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)89058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunico RL, Gooding KM, Wehr T, editors. HPLC and CE of Biomolecules. Bay Bioanalytical Laboratory; Richmond: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mant CT, Hodges RS. In: HPLC of Biological Macromolecules. Gooding KM, Regnier FE, editors. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2002. p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mant CT, Burke TWL, Hodges RS. Chromatographia. 1987;24:565. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker JM, Mant CT, Hodges RS. Chromatographia. 1987;24:832. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Vasil AI, Rehaume L, Mant CT, Burns JL, Vasil ML, Hancock RE, Hodges RS. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67:162. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Mehok AR, Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1043:9. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Mant CT, Farmer SW, Hancock RE, Vasil ML, Hodges RS. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413406200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau SYM, Taneja AK, Hodges RS. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JW, Kallenbach NR. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5256. doi: 10.1021/bi00438a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper TM, Woody RW. Biopolymers. 1990;30:657. doi: 10.1002/bip.360300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnichsen FD, Van Eyk JE, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8790. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou NE, Mant CT, Hodges RS. Pept Res. 1990;3:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blondelle SE, Ostresh JM, Houghten RA, Perez-Paya E. Biophys J. 1995;68:351. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell AW, Aguilar MI, Wettenhall RE, Hearn MT. Pept Res. 1995;8:160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodges RS, Burke TWL, Mant CT. J Chromatogr. 1988;444:349. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke TWL, Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Liq Chromatogr. 1988;11:1229. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges RS, Burke TWL, Mant CT. J Chromatogr. 1991;548:267. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)88608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husband DL, Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2000;893:81. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00751-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodges RS, Mant CT, Mant CT, Hodges RS. HPLC of Peptides and Proteins: Separation, Analysis and Conformation. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovacs JM, Mant CT, Hodges RS. Biopolymers (Pept Sci) 2006;84:283. doi: 10.1002/bip.20417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibue M, Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1080:49. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1043:99. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyes BE, Walker DG. J Chromatogr A. 1995;691:337. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkland JJ, Henderson JW, DeStefano JJ, van Straten MA, Claessens HA. J Chromatogr A. 1997;762:97. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNeff C, Zigan L, Johnson K, Carr PW, Wang A, Weber-Main AM. LC–GC. 2000;18:514. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivier J, McClintock R, Galyean R, Anderson H. J Chromatogr. 1984;288:303. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)93709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mant CT, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2002;972:101. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorsey JG, Foley JP, Cooper WT, Barford RA, Barth HG. Anal Chem. 1992;64:353R. doi: 10.1021/ac00036a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regnier FE. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:137. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills JB, Mant CT, Smillie LB, Hodges RS. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1133:248. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]