Abstract

Purpose

One goal of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System™ (PROMIS™) is to develop a measure of sexual functioning that broadens the definition of sexual activity and incorporates items that reflect constructs identified as important by patients with cancer. We describe how cognitive interviews improved the quality of the items and discuss remaining challenges to assessing sexual functioning in research with cancer populations.

Methods

We conducted 39 cognitive interviews of patients with cancer and survivors on the topic of sexual experience. Each of the 83 candidate items was seen by 5 to 24 participants. Participants included both men and women and varied by cancer type, treatment trajectory, race, and literacy level. Significantly revised items were retested in subsequent interviews.

Results

Cognitive interviews provided useful feedback about the relevance, sensitivity, appropriateness, and clarity of the items. Participants identified broad terms (eg, “sex life”) to assess sexual experience and exposed the challenges of measuring sexual functioning consistently, considering both adjusted and unadjusted sexual experiences.

Conclusions

Cognitive interviews were critical for item refinement in the development of the PROMIS measure of sexual function. Efforts are underway to validate the measure in larger cancer populations.

Keywords: Clinical Trials as Topic, Neoplasms, Patient Satisfaction, Psychometrics, Quality Indicators, Quality of Life, Sexuality, Treatment Outcome

Introduction

There are an estimated 11.4 million cancer survivors in the United States [1]. Many survivors consider sexual function to be an essential component of quality of life [2]. Sexual dysfunction as a result of cancer treatment can lead to loss of intimacy, disrupt relationships, create negative body image, and contribute to emotional distress. Identifying the presence and severity of such problems is increasingly viewed as critical for patient care [2-6]. However, despite these directives, evidence suggests that unmet patient needs persist and that patients and health professionals continue to have mismatched expectations regarding communication about sexuality and intimacy [4, 7].

Facilitating communication between patients and survivors and their physicians and evaluating clinical outcomes in research require valid outcome measures that can be used in a variety of contexts. However, few valid measures of sexual function are available for use along the continuum of care for different cancer types and stages and for both men and women of different ages, sexual orientations, relationship situations, literacy levels, and cultural backgrounds [8]. In a structured review of patient-reported sexual function questionnaires, Arrington and colleagues [9] found that many questionnaires did not apply to broad populations. Many were specific to men or women or were sexual orientation-specific [9]. Many measured satisfaction and functioning indirectly by using items, such as behavioral checklists, that addressed specific sexual activities but failed to link the activities to overall patient satisfaction. Identifying specific sexual activities is sometimes necessary to measure clinically meaningful changes in sexual functioning. However, relying solely on these activities reinforces a narrow view of sexuality focused on performance, which may be less applicable to diverse patient populations, including patients with cancer or those who may not be sexually active at the time of the assessment. Finally, although many of the measures assessed several common dimensions, including interest, desire, excitement/arousal, frequency of sexual activity, performance, importance, and satisfaction, Arrington and colleagues [9] concluded that the importance of these dimensions is indeterminable without input from patients.

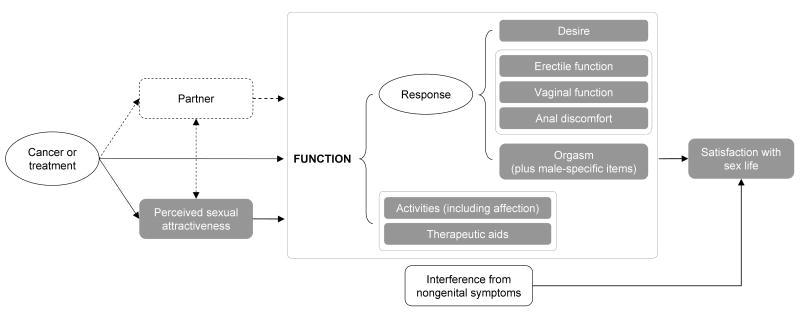

To address the limitations of existing measures used in cancer research, the National Institutes of Health Roadmap Initiative for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System™ (PROMIS™) and the National Cancer Institute funded the development of a measure of sexual function. The measure was intended to broaden the definition of sexual activity and to incorporate items that reflect constructs identified as important by patients with cancer [10, 11]. Our preliminary conceptual model includes constructs for perceived sexual attractiveness, response (ie, desire, erectile function, vaginal function, anal discomfort, orgasm), frequency of affectionate and sexual activities, use of therapeutic aids, interference from cancer-related symptoms, and satisfaction with sex life (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of the Sexual Function End Point

Shaded boxes represent proposed item banks. Dashed lines represent concepts not being measured as part of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

In this paper, we describe the results of using cognitive interviews to improve the quality of items that measure sexual experiences and discuss remaining challenges to assessing sexual functioning in cancer research highlighted by these interviews.

Methods

Preliminary measure development

Following a protocol developed by the PROMIS Steering Committee [12], we formed the PROMIS Sexual Function Domain Committee, a working group of oncologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, outcomes researchers, methodologists, and substantive experts in sexuality. We completed an extensive literature review to identify sexual function measures administered in cancer populations [8]. Similar to other literature reviews, we found that almost all existing measures included domains related to stages of the sexual response cycle defined by Masters and Johnson [13] (ie, excitement/arousal, plateau/continued arousal, and orgasm), though the specific content varied considerably between measures [9].

After reviewing items culled from the existing measures and conferring with 6 clinicians unaffiliated with PROMIS, we created a preliminary conceptual model (Figure 1). We assessed the adequacy of the conceptual model in 16 focus groups with 109 participants who were newly diagnosed, were currently undergoing treatment for cancer, or had completed treatment [14]. Focus group participants responded to open-ended inquiries about the scope and importance of sexuality and intimacy after a cancer diagnosis, and the causes and consequences of changes in sex life associated with cancer or its treatments.

We revised relevant items from existing measures and created new items to address conceptual gaps identified by the focus group participants [14]. Three members of the study team reviewed all of the items to ensure consistency in the responses. Prior to the cognitive interviews, we solicited reviews from 2 self-identified gay men and 2 self-identified lesbians. These reviewers provided feedback on whether the items were inclusive and sensitive with regard to sexual orientation. After a final review by an expert in measurement development from the National Cancer Institute, we had 47 revised items and 36 new items available for testing in cognitive interviews.

Cognitive interviews

Cognitive interviewing is a qualitative method applied to the development of questionnaires and other self-report measures [15, 16]. In brief, cognitive interviews empirically study the ways in which small groups of tested individuals mentally process and respond to questions. The interviews rely on intensive verbal probing of volunteer participants by a specially trained interviewer. Cognitive testing is designed to identify otherwise unobservable problems with item comprehension, recall, and other cognitive processes that can be remediated through question rewording, reordering, or more extensive instrument revision. The cognitive approach has been applied successfully in several domains related to quality of life and outcome measurement [17, 18].

After approval of the study by the institutional review board of the Duke University Health System, we recruited participants for the cognitive interviews from the Duke University tumor registry and oncology/hematology clinics. Consistent with the protocol developed by the PROMIS Steering Committee [12], each candidate item was seen by at least 5 participants, at least 1 of whom was nonwhite and 2 of whom had a low level of literacy. Participants were considered to have low literacy if they had less than a high school education or tested below the ninth-grade reading level on the Wide Range Achievement Test 4 (WRAT4) reading subtest. Participants received $50 in compensation.

The one-on-one, audio-recorded interviews were conducted in private rooms by a female interviewer for women and by a male interviewer for men. Each participant evaluated 30 to 33 items. For most items, participants were asked about the item immediately after answering it (ie, concurrent verbal probing), whereas other verbal probes asked about participants' answers for an entire set of items (ie, retrospective verbal probing). We developed all of the verbal probes by first considering potential sources of error for each item in the context of the Question Appraisal System (QAS) [16], a framework for identifying and organizing the types of errors that can occur in the administration of and response to a survey item. We reviewed each item in light of the QAS to derive hypotheses about potential errors and then designed item-specific probes to test for the occurrence of such errors. For example, some items used the term orgasm. This term might be a candidate for QAS category 3b, “Technical Terms.” Thus, items containing the term would include an explicit verbal probe to test the participant's understanding of the word orgasm. Such probes were also used to identify the best terms to use among candidate items with semantically redundant terms (eg, “sex life,” “sexual activity,” “having sex”).

In addition to item-specific verbal probes, interviewers were trained to record participants' understanding of the items, recall period, and reactions to the response options. The interviewers also asked if items were too sensitive or made inappropriate assumptions (eg, assumed participation in certain sexual activities or made assumptions about the participant's marital/partnered status). The interviewers were given scripted verbal probes and were trained to incorporate spontaneous verbal probes when appropriate. The interviewers were also trained to observe and record signs of apprehension and to allow participants to skip questions that made them uncomfortable.

After each round of cognitive interviews, we reviewed participants' comments and revised the items to address participants' concerns. We retested significantly revised items in another round of cognitive interviews with 3 additional participants, at least 1 of whom had low literacy.

Results and discussion

We conducted 39 cognitive interviews between April and October 2007. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants. The study population reflected a range of cancer types and stages. The greater number of women in the study was a result of the repeated cognitive interviews that were needed to clarify items in one of the women-specific item categories. In the sections that follow, we review our findings about the relevance of the items, recall period, wording changes to improve sensitivity, appropriateness, and clarity, and item ordering. We also discuss the assessment of sexual functioning without reference to specific activities and the challenges of addressing and measuring sexual functioning in the context of sexual experiences that include the use of sexual aids.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 24)a |

Men (n = 15)a |

All Participants (n = 39)a |

|

| Low literacy | 10 (41.7) | 6 (40.0) | 16 (41.0) |

| Nonwhite | 11 (45.8) | 4 (26.7) | 15 (38.5) |

| Sexually activeb | 19 (79.1) | 10 (66.6) | 29 (74.4) |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Stage 1+2 | 12 (50.0) | 7 (46.7) | 19 (48.7) |

| Stage 3+4 | 11 (45.8) | 7 (46.7) | 18 (46.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Cancer site | |||

| Breast | 9 (37.5) | 0 | 9 (23.1) |

| Colorectal | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Lung | 4 (16.7) | 2 (13.3) | 6 (15.4) |

| Prostate | 0 | 7 (46.7) | 7 (17.9) |

| Other | 10 (41.7) | 6 (40.0) | 16 (41.0) |

| Active treatment | 6 (25.0) | 2 (13.3) | 8 (20.5) |

Four participants (2 women and 2 men) participated in 2 rounds of the interviews.

Sexually active within the past 30 days.

Relevance of items

Although we attempted to create items that could be answered by anyone—both men and women, regardless of sexual orientation or marital/partnered status—many participants expressed that certain types of questions did not apply to them. For example, many men said that items about breast tenderness or enlargement and hot flashes applied only to women, though these can be side effects of cancer and its treatments for both men and women. Because these questions seemed to confuse some male participants, we elected to ask the questions of women only. Similarly, some participants assumed that items about rectal pain applied only to persons who engaged in anal sex, though patients with colorectal cancer may experience rectal discomfort during other sexual activities. These items made many participants uncomfortable, so for the purposes of later PROMIS item testing, we asked the questions about rectal pain only of participants who reported having engaged in anal sex during the previous 30 days. These findings highlight the need for PROMIS to provide explicit guidance about which subsets of items should be used in particular populations when the final measure is released.

Recall period

We assessed the recall period in one of two ways. First, when we asked participants to describe how they arrived at their answers, we recorded whether they made reference to a time frame and, if so, what time frame the participant said they considered. Second, for some items we asked specifically about what time frame the participants used when recalling their answers.

Most participants said that, when they were answering the questions, they were thinking of the past 30 days, the past 4 weeks, or the past month. Three participants reported they were considering the time since the beginning or end of their treatment (ie, a longer time frame than 1 month). In responding to the items, some participants wanted to rate even sexual experiences that had occurred before the 1-month recall period. For example, 2 participants stated they had answered the question in reference to their last sexual encounter, which had occurred months earlier. Three participants suggested that we consider extending the time period for rating the items. For example, 1 participant said, “Some patients have treatments that last 30 days and they come in 2 or 3 times a week. They may be so tired or sick they are unable to have sex…. [Thirty] days might be too short, because they might not have had a sex life in the past 30 days because of their treatment.” These responses suggest that some patients believe the priority in asking these questions should be on obtaining a personal judgment about an important life experience, rather than ensuring that the judgment is restricted to a particular recall period.

Self-report data from cognitive interviews is helpful in identifying cases in which participants said they constructed their answers in a way that was inconsistent with the intended time frame. However, even if participants said they used a 1-month recall period, the cognitive interview data cannot inform the accuracy of the participant's recall for a particular event. For this type of evaluation, a comparison with daily diary data would be more informative [19]. The PROMIS Sexual Function Domain Committee is currently conducting this study. Meanwhile, we will continue to use a 30-day reference period for the items.

Wording changes to improve sensitivity, appropriateness, and clarity

Participants identified problems with the wording of some items that prompted important revisions. It is instructive that participants identified these problems after many rounds of review by investigators and survey methodology specialists. We provide several examples below. Table 2 provides an example of how we evaluated the results of the interviews and modified the items based on participant feedback.

Table 2.

Example of Item Testing and Modification Using Participant Feedback

| Itemb | Overall Understandingc | Response Construction | Other Impressionsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round One | |||

| Original Item: “How often have you stopped sexual activity because of pain inside or outside your vagina?” 5 = Never 4 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes 2 = Often 1 = Always |

32, 10070: Participants did not understand “inside or outside your vagina.” If the goal was to ask about pain all over the body, participants suggested the item should be worded “pain anywhere on the body” or something similar. | LL281, 239, 10070: Participants thought there should be a response choice stating “Have not had sex in past 30 days.” | LL261: Participant thought this was a good question for doctors to ask and that people would be comfortable with the question. |

| LL35: Participant did not understand “outside the vagina.” The concept was not “important” to participant's sexual activity. | 32: Participant stated that she liked the never-rarely-sometimes-often-always better than the not at all-a little, etc. | 2630: Participant thought the question assumed there could be a reason for pain. | |

| LL144: Interpreted “pain inside or outside your vagina” as internal burning, rawness due to sexual activity, including within the abdominal area. | 32: Participant thought that 30 days was a good construction for recall, since her treatment segment helps to define time for her. | ||

| 2630, LL261: Participant understood the question to mean inside the vagina and the area immediately outside of the vagina. | |||

| 26: Participant interpreted “inside or outside your vagina” as inside the vagina or anywhere. Participant was unsure if the question was asking about the location of the pain or the fact that sexual activity stopped because of pain. | |||

| 239: Participant first said that the item was confusing, but then said that she understood. | |||

| LL280: Participant did not understand “inside or outside your vagina.” Participant was unsure what “outside your vagina” meant. She interpreted pain inside her vagina to mean the vagina was too dry. | |||

| LL281: Participant did not understand “inside or outside your vagina.” She thought about pain in the general vaginal area. | |||

| Round Two | |||

| Revised Item: “How often have you stopped sexual activity because of discomfort or pain in your vagina?”c 0 = Have not had any sexual activity in the past 30 days 5 = Never 4 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes 2 = Often 1 = Always |

2154, LL293: Participants thought about pain in the vagina when they answered the question. | ||

| LL294: To the participant “pain in your vagina” meant the vagina felt too dry or too tight and it was painful. | |||

Abbreviations: The number indicates the participant number. LL indicates that the participant had low literacy.

Includes sensitivity, recall, and assumptions.

The context for the item is “In the past 30 days…”

Final version of the item used in item testing.

Implied judgments in item wording

One of the original items read, “When having sex with a partner, how often have you needed fantasies to help you stay interested?” Two participants thought the word “needed” implied a negative judgment toward the use of sexual fantasies. We reworded the item to read, “When having sex with a partner, how often have you used fantasies to help you stay interested?” During retesting, no participant commented that the revised item implied a negative judgment.

Awkward descriptors of sexual experience

In an effort to develop a single item that assessed vaginal discomfort during sexual activity, we asked, “How would you rate the overall comfort of your vagina during sex?” Some participants had difficulty with the term overall comfort. One participant said, “I think of my sofa as being comfortable, not really my vagina during sex.” One participant said that the response options excellent to poor were “like a report card for your vagina.” We changed the response options to range from “very comfortable” to “very uncomfortable.” The item now reads, “How would you describe the comfort of your vagina during sexual activity?” When we retested the items, participants did not identify the wording as awkward or inappropriate.

High-literacy vocabulary

Participants with low literacy (n = 2) had difficulty with the term distracting thoughts in the item “How often have you lost your arousal (been turned off) because of distracting thoughts?” We retested the item as “How often have you lost interest once a sexual activity begins?” with 7 participants, and all participants who had low literacy (n = 3) said they understood and preferred the revised item.

Problems with item ordering

Cognitive interviews also identified confusion created by the order of some items. For example, we originally presented the item “Are you married or in a relationship that could involve sexual activity?” before the item “Over the past 30 days, have you had any type of sexual activity with another person?” Five out of 20 participants thought that the question was asking about sexual activity with someone other than their partner. In a subsequent round, we modified the second question to read, “Over the past 30 days, have you had any type of sexual activity with another person, including your partner?” and reversed the order of the 2 items. After making this change, the proportion of participants who had difficulty with the item was halved. We plan to evaluate the consistency of this item among other questions about sexual activity using data from a large sample from item testing.

Assessing sexual function and satisfaction without reference to specific activities

In an ideal measure of sexual functioning, any person who could claim to have a sexual component to his or her life would be eligible to receive a score on as many subdomains as possible. However, many existing instruments measure function and satisfaction with items that place the assessment in the context of specific sexual activities, which were often specific to either men or women. To ensure that our measure was broadly applicable, we first created a subdomain that asked about the frequency of performing various activities (eg, holding hands, kissing, sexual intercourse). Then, for the remaining items in the measure, we attempted to remove all references to specific activities. To accomplish the second goal, we needed to find a generic term to broadly describe sexual experience. We used verbal probes with the cognitive interview participants to identify inclusive ways to describe sexual intimacy. Participants identified sex life as the most encompassing term. For most of the participants, sex life included a range of sexual activities, including affectionate behavior, foreplay, and masturbation. Some participants mentioned that the term also included the emotions they experience in addition to physical activities. The term sexual activity was thought to be the second broadest term and, like sex life, was associated with a range of sexual activities, including masturbation, with less emphasis on the emotions experienced. Participants identified having sex as the most exclusive term, pertaining solely to sexual intercourse. Participants noted that the broad terms sex life and sexual activity made the items applicable to both men and women.

On a related note, participants repeatedly reported a preference for items that referred to emotional intimacy. Many participants liked the item “Over the past 30 days, how satisfied have you been with your ability to share warmth and intimacy with another person?” because it captured elements of an intimate relationship like eye contact, feeling close to someone, snuggling, and holding hands. All of the participants noted that the item “Over the past 30 days, how often have you and another person spent time holding or hugging each other romantically?” was an effective way to inquire about nonsexual aspects of relationships and intimacy. These results were consistent with findings from focus groups, in which participants identified emotional intimacy and affectionate behavior as a key part of their sex life [13]. These reactions also suggest that the inclusion of items on intimacy and affectionate behavior make important contributions to the face validity of the measure from the respondent's perspective.

Adjusted and unadjusted functioning: the case of sexual aids

Focus groups with men and women revealed the importance of sexual aids (eg, lubricants for women and erectile dysfunction drugs for men) to the sexual functioning of cancer survivors [14]. In developing the measure, we were interested in evaluating participants' sexual functioning as it occurred in their everyday lives. For example, if participants typically used sexual aids during sexual intercourse, we wanted them to respond to the items considering the times they were using these aids. Such an assessment is a measure of “adjusted functioning.” Several instruments have been developed to assess sexual functioning with therapeutic aids in men (eg, International Index of Erectile Function [20], University of California, Los Angeles, Prostate Cancer Index [21]). However, there are no validated instruments that address adjusted functioning in women.

We tested the erectile function and vaginal function items with instructions about sexual aids in a variety of formats. The instructions asked participants who regularly used therapeutic aids to describe their sexual experiences when using the aids. In the first round of interviews, we included the instructions before the set of items (Table 3). In the second round of interviews, we tested the items with a parenthetical phrase after each relevant item (Table 4). In both rounds of interviews, we found that, when answering items about erectile function, men consistently considered the use of therapeutic aids if they normally used them. However, when answering items about vaginal dryness and pain, women had more difficulty deciding whether to consider the times when they had used a personal lubricant during sexual activity. For example, some women thought they were to answer the question while considering the times when they used a lubricant, even if they had not used a lubricant in the past 30 days.

Table 3.

Instructions for Responding to Items Regarding the Use of Therapeutic Aids During Sexual Activity: Placement Before the Item Set

| Instructions for the Erectile Function Items |

| Some people use aids such as pills (for example, Viagra or Cialis) or other methods (for example, injections or a vacuum pump) to help them get and keep an erection. If you use any aids to help you get or keep an erection, please describe your experience when you are using the aid. |

| Instructions for the Vaginal Function Items |

| Some people use aids such as artificial lubrication (for example, K-Y Jelly) or other methods to help them during sexual activities. If you regularly use any aids during sexual activities, please describe your experience when you are using the aid. |

Table 4.

Instructions for Responding to Items Regarding the Use of Therapeutic Aids During Sexual Activity: Placement After Each Item

| Text of the Item for Men |

| If you use pills, injections or a penis pump to help you get an erection, please answer this question thinking about the times that you used these aids. |

| Text of the Item for Women |

| If you use an artificial lubricant such as K-Y Jelly during sexual activities, please answer this question thinking about the times that you used artificial lubricants. |

Since our goal was to achieve uniform interpretation of the items, we conducted a third round of cognitive interviews with women only, screening potential participants depending on how frequently they used vaginal lubricants. We classified 9 participants into 1 of 3 groups: “always” (n = 4), “sometimes”(n = 3), and “never”(n = 4). During the cognitive interview, the interviewer showed the participant the vaginal function items without reference to lubricants. After the participant had seen all of the items, the interviewer asked whether the participant had considered their use of lubricants during sexual activity when answering each question.

Although the participants had no difficulty understanding the questions, we found that women in the “sometimes” group differed from women in the “always” group with regard to whether they considered their use of lubricants during sexual activity when they responded to the questions. Furthermore, even within these groups, the participants differed in how they responded to the items. Among women who sometimes used lubricants, there were inconsistencies for two thirds of the 12 items, compared to inconsistencies for one third of the items among women who always used lubricants during sexual activity. In addition, participants were not consistent about whether they considered their use of sexual aids across different items. Some women indicated that they did not think about their use of lubricants when responding to items about arousal or foreplay, but they considered their use of lubricants when responding to items about sexual intercourse.

At the end of these interviews, we asked for feedback comparing the instructions from the first round of interviews (Table 3) and the parenthetical phrases used in the second round (Table 4). Participants did not consistently favor either approach, and only 1 participant said the instructions would have been helpful in answering the questions.

To our knowledge, no data have been published regarding how women interpret and respond to these types of questions. Thus, we have identified an important challenge that will likely be faced by any measure purporting to assess sexual functioning in women. The PROMIS team is initiating a diary study to examine sexual functioning and the use of personal lubricants on an event-by-event basis to determine (1) how women's general responses to the measure correspond to detailed reports of specific sexual activities and (2) whether a daily diary approach would be superior to a 30-day recall approach in measuring adjusted functioning. In the meantime, item testing in a large sample of patients with cancer will use the items without special instructions, similar to all other existing measures of sexual functioning in women.

Limitations of cognitive interviews for measure development

We have discussed many of the strengths and contributions of the cognitive interviews; however, there are some limitations inherent in the cognitive interview process. First, as with almost all empirical studies, the participants might not be representative of all potential respondents in terms of how they processed and responded to the items under study. Although there is no way to eliminate this limitation, its impact can be reduced by recruiting a sample that reflects variability in education and cultural background. Future research on measure development in sexual functioning and intimacy should consider qualitative feedback from additional populations who may have been underrepresented in this work, such as adolescents and patients and survivors who identify as homosexual or bisexual. Second, the results of the interviews highlight a problem but do not always lead directly to a solution, as with the items on vaginal function and the use of personal lubricants. In this case, further research is required to find the best way to properly address the issue.

Conclusion

The cognitive interview process was critical for the refinement of items that had already been subjected to extensive expert review. To our knowledge, this is the first time that cancer patients and survivors have been engaged in cognitive interviews to develop a measure of sexual functioning. Participants provided useful feedback on how they interpreted the items and how to make the questions more understandable. To make the measure broadly applicable, participants helped us identify the most inclusive terms to describe sexual activity and sex life. With the exception of the vaginal function items, we were generally able to use the participants' feedback to create a measure that will be interpreted as consistently as possible. Efforts are underway to validate the measure in a large population of cancer patients and survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was funded by grant U01AR052186 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, with additional support from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

PROMIS Sexual Function Domain Committee: Maria R. Fawzy, Kathryn E. Flynn, Tracey L. Krupski, Laura S. Porter, Rebecca Shelby, and Kevin P. Weinfurt (Duke University); Elizabeth A. Hahn (Northwestern University); and Diana D. Jeffery and Bryce B. Reeve (National Cancer Institute).

Additional Contributions: We thank Elizabeth Clipp of Duke University and Wendy Demark-Wahnefried of MD Anderson Cancer Center for assistance with PROMIS grant development; Denise Snyder of Duke University for assistance with data collection; Justin Levens and Chantelle Hardy of Duke University for conducting the cognitive interviews; Janice Tzeng of Duke University for research assistance; and Damon Seils of Duke University for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Facts Sheet. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: (based on November 2008 data submission). http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Cancer Survivorship. Improving Care and Quality of Life, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bober SL, Park ER. Let's talk about sex--and cancer. Boston Globe. 2008 January 7;:A11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schover LR. Sexuality and fertility after cancer. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:523–527. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krebs LU. Sexual assessment in cancer care: concepts, methods, and strategies for success. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(2):80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Sexuality and reproductive issues (PDQ®) 2004 Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/sexuality/healthprofessional.

- 7.Hordern A, Street A. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–227. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Hahn EA, Flynn KE, et al. Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1142–1153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arrington R, CoFrancesco J, Wu AW. Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(10):1643–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Medical Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, Flynn KE, Lad T, Lai JS, et al. Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: a patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(32):5106–5112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA, PROMIS Cooperative Group Evaluation of item candidates: the Promis qualitative item review. Medical Care. 2007;45(5):S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Response. Toronto; New York: Bantam; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn KE, Tzeng J, Jeffery DD, Reeve BB, Weinfurt KP, the PROMIS Sexual Function Domain Subcommittee Conceptualizations of sexual functioning and intimacy among cancer sufferers and survivors. Psychooncology. 2007;16(S2):S135–S136. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsyth BH, Lessler JT. Cognitive laboratory methods: a taxonomy. In: Biemer PP, Lyberg LE, Mathiowetz NA, Sudman S, editors. Measurement errors in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1991. pp. 393–418. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McColl E, Meadows K, Barofsky I. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology and quality of life assessment. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12(3):217–218. doi: 10.1023/a:1023233432721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis GB, Reeve BB, Barofsky I. The use of cognitive interviewing techniques in quality of life and patient-reported outcomes assessment. In: Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder C, editors. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer: Measures, Methods, and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, Vikingstad G, Pribbernow M, Grossman S, Stone AA. The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain. 2008;139(1):146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake B, Brook RH. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: Development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Medical Care. 1998;36(7):1002–1012. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]