Abstract

Background

China has been successful in breeding hybrid rice strains, but is now facing challenges to develop new hybrids with high-yielding potential, better grain quality, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. This paper reviews the most significant advances in hybrid rice breeding in China, and presents a recent study on fine-mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for yield traits.

Scope

By exploiting new types of male sterility, hybrid rice production in China has become more diversified. The use of inter-subspecies crosses has made an additional contribution to broadening the genetic diversity of hybrid rice and played an important role in the breeding of super rice hybrids in China. With the development and application of indica-inclined and japonica-inclined parental lines, new rice hybrids with super high-yielding potential have been developed and are being grown on a large scale. DNA markers for subspecies differentiation have been identified and applied, and marker-assisted selection performed for the development of restorer lines carrying disease resistance genes. The genetic basis of heterosis in highly heterotic hybrids has been studied, but data from these studies are insufficient to draw sound conclusions. In a QTL study using stepwise residual heterozygous lines, two linked intervals harbouring QTLs for yield traits were resolved, one of which was delimited to a 125-kb region.

Conclusions

Advances in rice genomic research have shed new light on the genetic study and germplasm utilization in rice. Molecular marker-assisted selection is a powerful tool to increase breeding efficiency, but much work remains to be done before this technique can be extended from major genes to QTLs.

Key words: Hybrid rice, cytoplasmic male sterility, inter-subspecies, DNA marker, molecular marker-assisted selection, quantitative trait loci

INTRODUCTION

Rice is a staple food in China, contributing 40 % to the total calorie intake of Chinese people. With the wide adoption of semi-dwarf varieties, rice yield in China increased from 2·0 t ha−2 in the 1960s to 3·5 t ha−2 in the 1970s. Subsequently, hybrid rice that has a yield advantage of 10–20 % over conventional varieties was developed and commercially grown. Together with the application of modern cultivation technology, the rice yield has risen to about 6·0 t ha−2. This has contributed to self-sufficiency of food supply in China.

However, the yield ceiling witnessed in various crop species (Mann, 1999) has also been encountered for rice production in China (Yang et al., 1996, 2004). In addition, arable land available for rice cultivation in China has decreased during the last three decades, reducing the area planted to rice from 36·2 × 106 ha2 in 1976 to 26·5 × 106 ha2 in 2003. As a consequence, the total output of rice grain has fallen from a record high of 200·7 × 106 t in 1997 to 160·7 × 106 t in 2003. To ensure food security for the increasing population, raising the yield ceiling of rice remains a priority in China (Table 1). At the same time, there is an increasing demand for improved grain quality and application of environmentally friendly farming systems.

Table 1.

Trend required in rice production and yield to maintain rice self-sufficiency in China

| Year | Total output (×106 t)* | Increase (%)† | Yield (t ha–2) | Increase (%)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 195·0 | 6·85 | 6·180 | 4·4 |

| 2010 | 217·5 | 19·18 | 6·885 | 16·3 |

| 2030 | 247·5 | 35·62 | 7·845 | 32·6 |

* Estimated based on the per capita rice consumption of 150 kg and the rice cropping area of 31·57 × 106 ha2.

† In comparison with 1995.

With advancements in rice breeding in China, and inspired by the conceptualization and experience of new plant type breeding at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), a national collaborative research programme on the breeding of super high-yielding rice (‘super rice’) was established by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) in 1996. The breeding strategy was to combine the formation of an ideal plant type with the exploitation of heterosis. Its implementation involved equal attention to three- and two-line hybrid rice, and to hybrid rice and conventional varieties. In addition to meeting grain quality and pest resistance requirements, a super rice variety should have a plant type that meets the yield target under favourable conditions. The super rice breeding programme in China has had two phases, 1996–2000 and 2001–2005, and the yield targets were defined for each phase. A rice variety could be recognized as a super rice if it meets the yield target in two pilot sites in two successive years, or if it meets the goal of yield advantage over the control variety in regional yield trials (Table 2).

Table 2.

Yield target of super high-yielding rice varieties (the Ministry of Agriculture, P.R. China, 1996)

| Conventional rice (t ha–2)* |

Hybrid rice (t ha–2)* |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | EI(Y) | E&LI(S) | SJ(Y) | SJ(N) | EI(Y) | SI&J | LI | Increase (%)† |

| 1996–2000 | 9·00 | 9·75 | 9·75 | 10·50 | 9·75 | 10·50 | 9·75 | 15 |

| 2001–2005 | 10·50 | 11·25 | 11·25 | 12·00 | 11·25 | 12·00 | 11·25 | 30 |

* Performance at two sites, 6·67 ha2 or more at each site, in two successive years. EI(Y), early-season indica rice in middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River; E&LI(S), early- or late-season indica rice in southern China; SJ(Y), single-season japonica rice in middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River; SJ(N), single-season japonica rice in northern China; SI&J, single-season indica or japonica rice; LI, late-season indica rice.

† Yield advantage in the regional yield trials over the control variety which was used in 1990 in the same trial.

In the Chinese super rice breeding programme, new plant type models were modified from the IRRI's concept and diversified according to different rice regions in China. New male sterile germplasms and inter-subspecies (indica × japonica) crosses were used to broaden the genetic base of parental lines. In addition, molecular breeding techniques were applied. Consequently, between 2001 and 2005 a number of rice varieties that achieved the yield goal were developed.

In this paper, we review the development of hybrid rice breeding in China, with emphasis on the recent advances to diversify male sterile cytoplasm, utilization of inter-subspecies crosses and the application of DNA markers. Recent work on fine-mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for yield-related traits is also presented.

HYBRID RICE IN CHINA

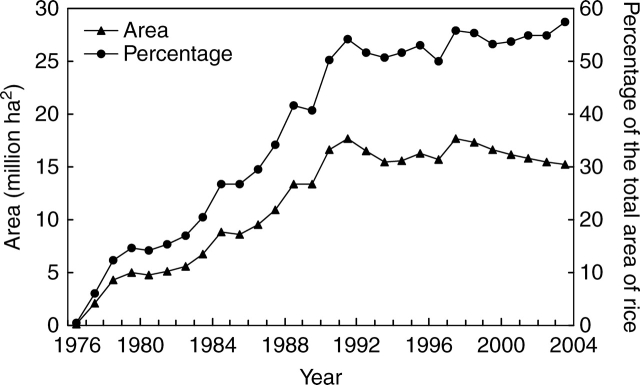

As rice is a self-pollinated species, use of male sterility is essential for hybrid rice breeding and seed production. China initiated research on hybrid rice in 1964 and became the first country to produce hybrid rice commercially. Hybrid rice breeding has been based on using cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) or photo-thermo genetic male sterility (P-TGMS). A breeding system using three lines (a CMS line, and CMS maintainer and CMS restorer lines) was established in 1973, and commercial production of hybrid rice started in 1976 (Yuan, 1986). A two-line hybrid rice system using P-TGMS was established in the 1980s, and two-line hybrid rice was widely used by 1998 (Yuan and Tang, 1999). At the time of writing, hybrid rice occupies more than 50 % of the total rice area in China (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Acreage under hybrid rice in 1976–2003 in China.

Wild-abortive CMS (CMS-WA) was the first type of male sterility used in hybrid rice breeding, and it has continued to be the main type of CMS used in terms of the number of hybrids developed and the total area planted to those hybrids. The major hybrid rice combinations in China are derived from a few CMS and restorer lines, and these few widely used combinations have been grown for some time (Cheng, 2000; Cheng and Min, 2000). The most popular WA-type hybrid, Shanyou 63, was planted on a total acreage of 62 × 106 ha2 between 1984 and 2003, occupied the largest acreage for a single hybrid from 1987 to 2001, and had the highest annual acreage of over 6·67 × 106 ha2 in 1990. Concerns regarding the genetic vulnerability of hybrid rice arose, and insufficient genetic diversity was considered to be a major reason why rice yields plateaued (Cheng and Min, 2000). During the last decade, great attention has been paid to broaden the genetic diversity of hybrid rice.

Diversification of male sterile cytoplasm used in three-line hybrid rice

To broaden the genetic diversity of hybrid rice, Chinese rice researchers have sought to exploit new types of cytoplasm for male sterility. Thus far, eight types of CMS have been commercially used for rice production. The proportions of CMS-ID and CMS-G&D hybrid rice in the total area growing three-line hybrid rice have increased in recent years (Table 3). In 2002, the planting area of CMS-ID hybrid II You 838 and CMS-G hybrid Gangyou 725 were 0·65 × 106 ha2 and 0·64 × 106 ha2, respectively, being higher than the area of 0·55 × 106 ha2 for CMS-WA hybrid Shanyou 63. Although the areas for CMS-WA hybrids remain dominant over other type of hybrids, this was the first time that the area for a single hybrid developed from a CMS type other than WA had exceeded CMS-WA hybrid planting area.

Table 3.

Planting areas and proportion of three-line hybrid rice classified based on CMS types in 2000–2002 in China

| 2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMS* | Acreage (×106 ha2) | % | Acreage (×106 ha2) | % | Acreage (×106 ha2) | % |

| WA | 6·53 | 51·45 | 7·01 | 56·47 | 6·03 | 48·06 |

| ID | 2·85 | 22·44 | 2·53 | 20·36 | 3·33 | 26·56 |

| G&D | 1·78 | 13·99 | 1·76 | 14·21 | 2·21 | 17·66 |

| DA | 1·33 | 10·48 | 0·79 | 6·39 | 0·70 | 5·61 |

| HL | 0·02 | 0·15 | 0·02 | 0·18 | 0·05 | 0·38 |

| K | 0·13 | 1·00 | 0·22 | 1·79 | 0·11 | 0·90 |

| BT | 0·06 | 0·49 | 0·07 | 0·60 | 0·11 | 0·85 |

* CMS, cytoplasmic male sterility. WA, the male sterile cytoplasm was originated from a male sterile plant in a population of Asian common wild rice (Oryza rufipogon) in Hainan, China; ID, originated from rice line Indonesia Paddy 6; G, originated from rice line Gambiaka. D, originated from an F7 population of (Dissi D52 × 37) × Ai-Jiao-Nan-Te; DA, originated from a dwarf plant of O. rufipogon from Dongxiang, Jiangxi, China; HL, originated from a cross between O. rufipogon and rice line Lian-Tang-Zao; K, originated from an F2 population (K52 × Lu-Hong-Zao 1) × Zhen-Xin-Nian 2; BT, originated from the rice line Chinsurah Boro II.

The rapid increase in the use of CMS-ID hybrids is largely attributed to the high outcrossing rate and better grain quality of CMS-ID germplasm. The high outcrossing rate of CMS-ID lines results in a higher yield of hybrid seeds, reducing the cost of hybrid rice production. In addition, a number of CMS-ID lines, such as Zhong 9A developed by the Chinese National Rice Research Institute (CNRRI), have shown improved grain quality compared with CMS-WA lines such as Zhenshan 97 A (Table 4).

Table 4.

Performance of grain quality traits of CMS lines Zhong 9A and Zhenshan 97A

| CMS line |

National standard* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Zhong 9A | Zhenshan 97A | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Brown rice recovery (%) | 80·4 | 81·0 | ≥79·0 | ≥77·0 | ≥75·0 |

| Milled rice recovery (%) | 71·1 | 73·3 | – | – | – |

| Head rice recovery (%) | 31·3 | 34·2 | ≥56·0 | ≥54·0 | ≥52·0 |

| Grain length (mm) | 6·7 | 5·8 | – | – | – |

| Grain length/width ratio | 3·1 | 2·3 | ≥2·8 | ≥2·8 | ≥2·8 |

| Chalky grain percentage | 8 | 84 | ≤10 | ≤20 | ≤30 |

| Chalkiness (%) | 0·6 | 16·6 | ≤1·0 | ≤3·0 | ≤5·0 |

| Translucency | 3 | 4 | – | – | – |

| Alkali digestion value | 6 | 6 | – | – | – |

| Gel consistency (mm) | 32 | 30 | ≥70 | ≥60 | ≥50 |

| Amylose content (%) | 23·7 | 22·7 | 17–22 | 16–23 | 15–24 |

* National Standard for High Quality Paddy, P. R. China. GB/T 17891-1999. – indicates no requirements.

Utilization of inter-subspecies crosses of rice

The use of indica × japonica crosses has long been considered a promising approach to broadening the genetic diversity and enhancing the heterosis of rice. However, F1 semi-sterility has generally been encountered in inter-subspecies crosses of rice, making it meaningless for direct use in hybrid rice breeding. In addition, distant crosses do not always increase F1 yield, and this is particularly true when the parental lines belong to different subspecies (Zhang et al., 1996; Xiao et al., 1996; Saghai Maroof et al., 1997).

It is now considered that indica-inclined or japonica-inclined lines are generally advantageous for a higher F1 yield (Mao, 2000). In recent decades, in areas of China that grow indica rice, breeding programmes have integrated japonica components into indica background, and in regions growing japonica rice they have integrated indica components into japonica background. By this means, a series of indica-inclined or japonica-inclined rice lines have been developed and employed as parental lines to develop super rice varieties.

The three-line hybrid rice Xieyou 9308 developed by the CNRRI and two-line hybrid rice Liangyou Pei 9 developed by the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Hunan Hybrid Rice Research Center are examples of the application of these indica- and japonica-inclined parents. Xieyou 9308 was bred by crossing restorer line R9308 to CMS line Xieqingzao A, in which R9308 was developed from the inter-subspecies cross C57 (japonica) × [No. 300 (japonica) × IR26 (indica)] and estimated to have 25 % japonica genetic components. Liangyou Pei 9 was bred by crossing indica variety 9311 to P-TGMS line Peiai 64S. Peiai 64S is an indica-inclined rice line developed by transferring genes conditioning P-TGMS from the japonica line Nongken 58S to Peiai 64 that was derived from a cross involving indica and tropical japonica germplasm. The super high-yielding potential of Xieyou 9308 and Liangyou Pei 9 has been well demonstrated under high-yielding cultivation conditions (Table 5). Xieyou 9308 was planted on a total area of 0·67 × 106 ha2 between 1999 and 2003, and Liangyou Pei 9 has become the hybrid with largest planting area since 2002.

Table 5.

Yield performance of F1 hybrid rice Xieyou 9308 and Liangyou Pei 9

| Hybrid | Trial site | Year | Average yield (t ha–2) | Acreage (ha2) | Highest yield (t ha–2) | Acreage (ha2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xieyou 9308 | Xinchang, Zhejiang | 2000 | 11·84 | 6·8 | 12·22 | 0·07 |

| Zhuji, Zhejiang | 2000 | 11·42 | 10·0 | 11·69 | 0·13 | |

| Xinchang, Zhejiang | 2001 | 11·95 | 6·9 | 12·40 | 0·07 | |

| Xinchang, Zhejiang | 2002 | 10·52 | 70·0 | 11·46 | 16·70 | |

| Xinchang, Zhejiang | 2003 | 11·54 | 82·5 | 12·03 | 28·87 | |

| Lianyou Pei 9 | Longshan, Hunan | 2000 | 10·65 | 66·7 | 11·13 | 0·07 |

| Chunzhou, Hunan | 2000 | 11·67 | 7·7 | 12·12 | 0·69 |

APPLICATION OF DNA MARKERS

As a result of the development of rice genomic research since the late 1980s, the knowledge acquired and technologies developed have opened new opportunities for rice breeding. Among uses that have been made of these technologies is selection of DNA markers for subspecies classification of parental lines, and integration of marker-assisted selection (MAS) into hybrid rice breeding programmes.

Selection of DNA markers for subspecies differentiation in rice

Subspecies classification of rice cultivars, especially the parental lines to be used in the breeding programme, has always been a subject of importance for rice breeders. While Cheng's index (Cheng, 1985) based on six morphological and biochemical traits has been extensively used, DNA markers have offered a new approach that is more effective and reliable (Wang and Tanksley, 1989; Neeraja et al., 2003).

In a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) marker-based phylogenetic analysis of wide-compatibility varieties in rice, 68 out of the total 160 RFLP probes displayed different hybridization patterns between the indica testers and japonica testers (Qian et al., 1994). Thirteen of these probes were established as core probes for subspecies differentiation (Qian et al., 1995). Subsequently, 54 indica varieties and 31 japonica varieties were analysed with additional probes. Twenty-eight RFLP markers distributing on 12 rice chromosomes were selected and used to estimate the subspecies index of rice lines in one double haploid (DH) and one recombinant inbred line (RIL) population. The RFLP marker-based index was found to be highly correlated to the morphological index (Mao, 2000).

Although RFLP analysis is reliable for subspecies classification in rice, technical complexity and costs make it inappropriate for use in the general breeding programmes. Given that simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers are technically easy and less expensive to use, SSR markers were screened for subspecies differentiation when the rice microsatellite framework map became available (Chen et al., 1997). A set of 21 SSR markers distributed on the 12 rice chromosomes were selected (Fan et al., 1999) and adopted by the breeders for parental selection and hybrid rice evaluation.

MAS for the development of restorer lines

Since the late 1990s, MAS has been extensively applied in the rice breeding programmes in China, especially for the improvement of bacterial blight (BB) resistance in restorer lines (Chen et al., 2000, 2001; Huang et al., 2003).

Having introduced IRBB lines carrying single and multiple BB resistance genes developed by the IRRI (Huang et al., 1997), these lines were tested against Chinese BB races and used in the breeding programmes in China. Two breeding schemes were applied at the CNRRI. In one scheme, backcrossing was made using local restorer lines as the recurrent parents and IRBB lines as the donors for BB resistance. While conventional selection was performed, MAS was applied at each generation to select individuals carrying the resistance allele. In the other scheme, the population was advanced to F5∼F7 with primary selection using conventional tools. MAS was then applied to select individuals carrying homozygotes of the resistance gene(s). New restorer lines developed were crossed to CMS lines for breeding hybrid rice combinations. This resulted in hybrid rice Xieyou 218 being released in 2002, which is believed to be the first time that a rice variety developed through MAS was used commercially in China. More hybrid combinations developed with the aid of MAS have been released since and were planted on 66·7 × 103 ha2 in 2005 (Cheng et al., 2004).

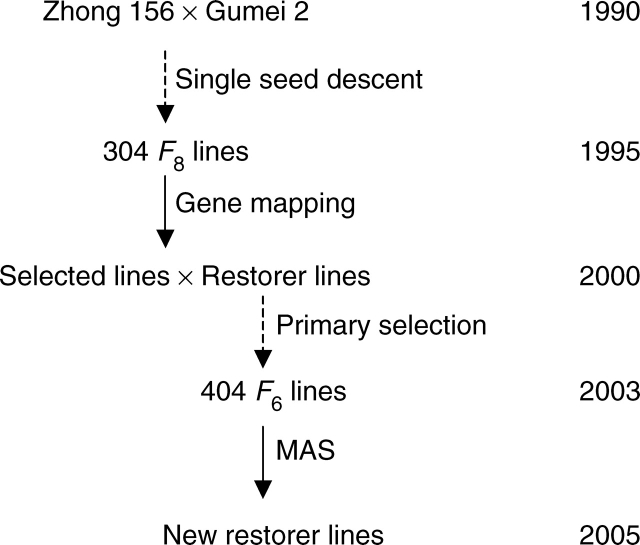

Gene-mapping studies have been integrated into MAS practice. An example is the transfer of a gene cluster for blast resistance to restorer lines (Fig. 2). By using 304 RILs of indica rice cross Zhong 156 × Gumei 2 and a linkage map of 181 markers, a gene cluster responsible for blast resistance to multiple blast isolates was located on chromosome 6 (Wu et al., 2005). From lines carrying the resistance gene cluster Pi25(t)–Pi26(t), three lines showing favourable performance based on heading date, plant height and spikelet fertility were selected and crossed to two newly developed restorer lines. Primary selections for heading date, plant height, plant type and spikelet fertility were performed at each generation. A total of 404 F6 lines were obtained in 2003. They were assayed with sequence tagged site (STS) and SSR markers linked to the blast resistance gene cluster (Wu et al., 2005) and SSR markers linked to the fertility-restoring genes (Li et al., 2005). Consequently, new restorer lines carrying the resistance gene cluster and exhibiting resistance to multiple blast isolates were developed.

Fig. 2.

Time frame for transferring a gene cluster for blast resistance from Gumei 2 to restorer lines.

QTL MAPPING FOR YIELD TRAITS USING STEPWISE RESIDUAL HETEROZYGOUS LINES

Grain yield and its component traits have always been a major objective of QTL analysis in rice. Of 7926 QTLs documented in Gramene, 1908 fall into the trait category of yield (http://www.gramene.org). A number of groups have employed QTL mapping to determine the genetic basis of heterosis in high-yielding rice hybrids (Xiao et al., 1995; Yu et al., 1997; Li et al., 2001; Zhuang et al., 2001; Hua et al., 2002). Although no general conclusions could be drawn from these studies, it is clear that both within-locus and inter-locus interactions play important roles in the genetic control of heterosis in rice. It is noteworthy that heterozygotes show no yield advantage at the majority of QTLs detected in populations that are derived from highly heterotic hybrids (Xiao et al., 1995; Zhuang et al., 2001; Hua et al., 2002), and the most frequent epistasis detected was additive × additive interaction (Yu et al., 1997; Zhuang et al., 2000). A full understanding of heterosis will depend on cloning and functional analysis of genes that are related to heterosis (Xu, 2003).

Development of mapping populations that segregate for a single QTL region in an inbred background is a prerequisite for QTL fine-mapping and positional cloning. In addition to classical near isogenic lines (NILs) that contain a small introgressed fragment in an isogenic background, a residual heterozygous line (RHL) that has a heterozygous segment at the target QTL region in an inbred background of parental mixtures could also be used for QTL fine mapping (Yamanaka et al., 2005). An RHL is equivalent to F1 individuals that are produced by crossing a pair of NILs differing at the target region. With the availability of a high-density molecular linkage map, a series of RHLs with overlapping heterozygous segments in the target region (we denote such a series as stepwise RHLs) could be selected from a segregating population derived from the original RHL. Using stepwise RHLs, the sample size required for QTL fine mapping is much smaller than for usual fine mapping studies. An example of the application of stepwise RHLs for fine mapping QTLs for yield traits in rice is given below.

Development of stepwise RHLs

An indica rice cross Zhenshan 97B × Milyang 46 was made in 1993, in which Zhenshan 97B (ZS97B) and Milyang 46 (MY46) are the maintainer and restorer lines of the commercial three-line hybrid rice Shanyou 10, respectively. Three sets of RILs at F7 were each derived from a single F1 plant by single seed descent. One set of the RIL population consisting of 252 lines was used for primary QTL mapping. In a segment on the short arm of chromosome 6, QTLs for many traits including yield traits were detected (Zhuang et al., 2002; Dai et al., 2005). The remaining sets of RILs consisting of totally 461 lines were used for RHL selection.

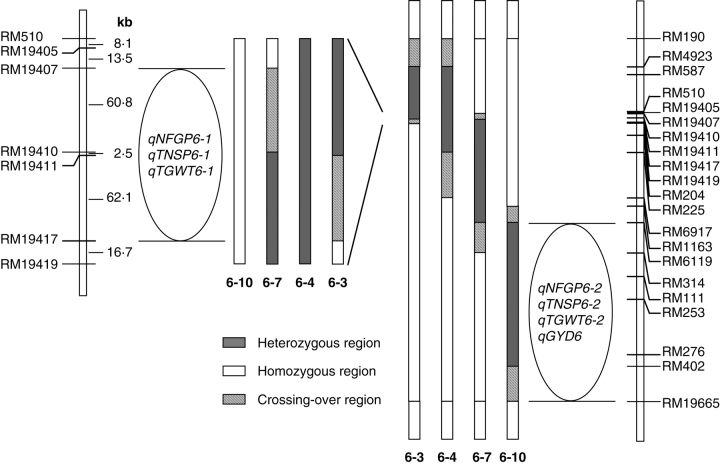

A single plant of each line was analysed with SSR markers distributing on the 12 chromosomes of rice, and an RHL carrying a heterozygous segment that covers a major portion of the short arm of rice chromosome 6 was selected. An F2:3 population was constructed from the selfed seeds of this RHL. SSR analysis was applied to 221 F2 plants and then to 332 F3 plants in 23 families. Four F3 individuals were selected to establish a set of RHLs with overlapping heterozygous segments in a 4·2-Mb region from RM4923 to RM402 (Fig. 3). New F2 populations were derived from selfed seeds of the RHLs. The RHLs were named as 6-3, 6-4, 6-7 and 6-10, and the corresponding F2 populations as FM6-3, FM6-4, FM6-7 and FM6-10, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Genotype constitution of RHLs 6-3, 6-4, 6-7 and 6-10 in the region extending from SSR markers RM190 to RM19665 on the short arm of chromosome 6 and two blocks of yield-related QTLs detected in this region. Right: the whole segment showing all the polymorphic SSR markers used and a block of QTLs that were detected in the F2 population derived from RHL 6-10 and located between RM6119 and RM19665. Left: the amplified portion extending from RM510 to RM19419, indicating a finely mapped block of QTLs that were detected in the F2 populations derived from RHLs 6-3, 6-4 and 6-7 and located between RM19407 and RM19417.

Fine mapping QTLs for yield traits using F2 populations derived from stepwise RHLs

Four F2 populations, including FM6-3 of 252 plants, FM6-4 of 680 plants, FM6-7 of 245 plants and FM6-10 of 880 plants, were grown from November, 2005 to April, 2006 in Lingshui, Hainan Province, China. Grain yield (GYD), number of panicles (NP), number of filled grains per panicle (NFGP), total number of spikelets per panicle (TNSP), spikelet fertility (SF) and 1000-grain weight (TGWT) were scored. Segmental linkage maps were constructed for each population and employed to determine QTLs using Composite Interval Mapping of Windows QTL Cartographer 2·5 (Wang et al., 2006). A threshold of LOD > 2·0 was used to claim a putative QTL.

In populations FM6-3, FM6-4 and FM6-7, QTLs were detected for NFGP, TNSP, SF and TGWT (Table 6), whereas no QTLs were detected for the two other traits, GYD and NP. The genetic mode of action and the direction of the additive and dominance effects of a QTL for a given trait were consistent across the three populations for traits NFGP, TNSP and TGWT, but the genetic mode of action and the direction of the additive effect varied for SF. These results suggested that the same set of QTLs for NFGP, TNSP and TGWT segregated in these populations, whereas different QTLs for SF might segregate in different populations. Because the common heterozygous segments presented in RHLs 6-3, 6-4 and 6-7 included the verified heterozygous segment RM19410–RM19411, and the possible heterozygous segments RM19407–RM19410 and RM19411–RM19417 in which crossing-over had occurred (Fig. 3), the location for qNFGP6-1, qTNSP6-1 and qTGWT6-1 was delimited to a 125-kb region flanked by RM19407 and RM19417.

Table 6.

QTLs for yield traits detected in four F2 populations

| Trait* | Population | LOD | A† | D‡ | D/[A] | R2 (%)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFGP | FM6-3 | 3·6 | −3·57 | −2·43 | −0·68 | 6·3 |

| NFGP | FM6-4 | 33·2 | −8·34 | −4·58 | −0·55 | 20·1 |

| NFGP | FM6-7 | 9·7 | −8·23 | −1·95 | −0·24 | 16·7 |

| TNSP | FM6-3 | 11·2 | −7·54 | −3·56 | −0·47 | 18·4 |

| TNSP | FM6-4 | 58·3 | −12·58 | −8·09 | −0·64 | 32·6 |

| TNSP | FM6-7 | 11·2 | −8·58 | −4·32 | −0·50 | 18·9 |

| SF | FM6-3 | 6·0 | 2·24 | 0·10 | 0·04 | 10·5 |

| SF | FM6-4 | 11·7 | 1·77 | 1·66 | 0·94 | 7·7 |

| SF | FM6-7 | 2·8 | −1·28 | 2·08 | 1·63 | 5·1 |

| TGWT | FM6-3 | 7·3 | 0·18 | 0·51 | 2·83 | 12·7 |

| TGWT | FM6-4 | 8·5 | 0·41 | 0·50 | 1·22 | 8·1 |

| TGWT | FM6-7 | 6·1 | 0·28 | 0·57 | 2·04 | 10·8 |

| NFGP | FM6-10 | 12·6 | −3·44 | 1·78 | 0·52 | 6·4 |

| TNSP | FM6-10 | 13·9 | −4·39 | 1·02 | 0·23 | 7·0 |

| SF | FM6-10 | 2·5 | 0·13 | 0·85 | 6·54 | 1·3 |

| TGWT | FM6-10 | 7·0 | −0·20 | 0·23 | 1·15 | 3·7 |

| GYD | FM6-10 | 4·7 | −1·23 | 0·39 | 0·32 | 2·4 |

* NFGP, number of filled grains per panicle; TNSP, total number of spikelets per panicle; SF, spikelet fertility; TGWT, 1000-grain weight; GYD, grain yield.

† Additive effect. Refers to the genetic effect of the putative QTL when a maternal allele was replaced by a paternal allele.

‡ Dominance effect.

§ Amount of variance explained by the putative QTL.

In population FM6-10, which only had a small overlapping with FM6-7 and had no overlapping with FM6-3 and FM6-4, QTLs were detected for NFGP, TNSP, TGWT, SF and GYD (Table 6), indicating another set of QTLs segregated in population FM6-10. It was noted that the allelic direction of qSF6-2 differed from other QTLs in this region, and this QTL was detected with a marginal LOD score of 2·4 and a small R2 of 1·3 %, suggesting caution regarding its claim as a QTL. Other QTLs were detected at LODs score of 4·7 or higher, among which qNFGP6-2 and qTNSP6-2 had higher LOD scores of 12·6 and 13·9, respectively. In addition, qNFGP6-2, qTNSP6-2 and qGYD6-2 had the same genetic mode of action and direction of QTL effects, suggesting that the effect of qGYD6-2 may be in fact attributed to qNFGP6-2 or qTNSP6-2. As these QTLs were located in an interval of about 2 Mb, more RHLs with smaller heterozygous segments are to be constructed for narrowing the QTL interval. Nonetheless, two linked intervals harbouring QTLs for yield traits were resolved and one was fine mapped in this study, illustrating that QTL fine mapping could be greatly facilitated by the application of stepwise RHLs.

CONCLUSIONS

It is 30 years since the first commercial release of hybrid rice. Hybrid rice has spread such that now it commands about 50 % of the total rice area in China. New male sterile cytoplasm sources and inter-subspecies crosses have contributed to the development of super rice breeding in China. However, sustainable improvements of hybrid rice yield potential, grain quality, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses continue to be a great challenge.

Exploitation of new germplasm has always played a critical role in rice breeding, and this will continue. Advances in rice genomic research has opened new avenues to detect beneficial alleles from unadapted and adapted germplasms, to study the molecular basis for variation in important agronomic traits, and to apply new tools for manipulation of both qualitative and quantitative traits. With the high-throughput and gene-based evaluation of rice germplasm, the efficiency of germplasm utilization could be greatly improved. More alleles from unadapted germplasm might be introgressed to improved varieties, and more gene pyramids constructed.

Molecular MAS has begun to contribute to the improvement of hybrid rice, especially for major genes conferring disease resistance. The integration of MAS and conventional means are becoming a routine approach in rice breeding. However, major genes available for MAS are insufficient, and MAS for complex traits has not been established. It is anticipated that the availability of the full sequence of the rice genome will greatly speed up the fine-mapping and cloning of rice genes. With the accumulation of genes isolated and a better understanding of the genetic basis of heterosis, new genotypes of rice may be designed by using genomic methods in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Chinese Super Rice Breeding Program, the Chinese 863 Program and NSFC grant 30571062. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the OECD.

LITERATURE CITED

- Chen S, Lin XH, Xu CG, Zhang Q. Improvement of bacterial blight resistance of ‘Minghui 63’, an elite restorer line of hybrid rice, by molecular marker-assisted selection. Plant Breeding. 2000;40:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Xu CG, Lin XH, Zhang Q. Improving bacterial blight resistance of ‘6078’, an elite restorer line of hybrid rice, by molecular marker-assisted selection. Crop Science. 2001;120:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Temnykh S, Xu Y, Cho YG, McCouch SR. Development of a microsatellite framework map providing genome-wide coverage in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:553–567. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K-S. A statistical evaluation of the classification of rice cultivars into hsien and keng subspecies. Rice Genetics Newsletter. 1985;2:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-H. Current status and prospect in the development of breeding materials and breeding methodology of hybrid rice. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 2000;14:165–169. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-H, Min S-K. Rice varieties in China: current status and prospect. Rice in China. 2000;1:13–16. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-H, Zhuang J-Y, Cao L-Y, Chen S-G, Peng Y-C, Fan Y-Y, et al. Molecular breeding for super rice in China. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 2004;18:377–383. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Dai W-M, Zhang K-Q, Duan B-W, Zheng K-L, Zhuang J-Y, Cai R. Genetic dissection of silicon content in different organs of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Crop Sci. 2005;45:1345–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y-Y, Zhuang J-Y, Wu J-L, Zheng K-L. SSLP-based subspecies identification in Oryza sativa L. Rice Genetics Newsletter. 1999;16:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hua JP, Xing YZ, Xu CG, Sun XL, Yu SB, Zhang Q. Genetic dissection of an elite rice hybrid revealed that heterozygotes are not always advantageous for performance. Genetics. 2002;162:1885–1895. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N, Angeles ER, Domingo J, Magpantay G, Singh S, Zhang G, et al. Pyramiding of bacterial blight resistance genes in rice: marker-assisted selection using RFLP and PCR. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Huang T-Y, Li S-G, Wang Y-P, Li H-Y. Accelerated improvement of bacterial blight resistance of ‘Shuhui 527’ using molecular marker-assisted selection. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology. 2003;19:153–157. (in Chinese with English abstract) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-X, Tu G-Q, Zhang K-Q, Yao F-Y, Zhuang J-Y. SSR marker-based mapping of fertility-restoring genes in rice restorer line Milyang 46. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 2005;19:506–510. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Li Z-K, Luo LJ, Mei HW, Wang DL, Shu QY, Tabien R, et al. Overdominant epistatic loci are the primary genetic basis of inbreeding depression and heterosis in rice. I. Biomass and grain yield. Genetics. 2001;158:1737–1753. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.4.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CC. Crop scientists seek a new revolution. Science. 1999;283:310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Mao C-Z. Differentiation of indica and japonica in two rice genetic population and the relationship between parental differentiation and heterosis. China: MSc Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences; 2000. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Neeraja CN, Malathi S, Siddiq EA. Microsatellites as diagnostic markers for differentiating Indica and Japonica subspecies of Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.) Rice Genetics Newsletter. 2003;20:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Qian H-R, Shen B, Lin H-X, Zhuang J-Y, Lu J, Zheng K-L. Screening of subspecies differentiating RFLP markers and phylogenetic analysis of wide compatibility varieties in Oryza sativa. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 1994;8:65–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00222395. (in Chinese with English abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H-R, Zhuang J-Y, Lin H-X, Lu J, Zheng K-L. Identification of a set of RFLP probes for subspecies differentiation in Oryza sativa L. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1995;90:878–884. doi: 10.1007/BF00222026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghai Maroof MA, Yang GP, Zhang QF, Gravois KA. Correlation between molecular marker distance and hybrid performance in US Southern long grain rice. Crop Science. 1997;37:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng Z-B. Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5. Raleigh, NC: Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University; 2006. (http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm. ) [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Tanksley SD. Restriction fragment length polymorphism in Oryza sativa L. Genome. 1989;32:1113–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J-L, Fan Y-Y, Li D-B, Zheng K-L, Leung H, Zhuang J-Y. Genetic control of rice blast resistance in the durably resistant cultivar Gumei 2 against multiple isolates. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;111:50–56. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Li J, Yuan L, Tanksley SD. Dominance is the major genetic basis of heterosis in rice as revealed by QTL analysis using molecular markers. Genetics. 1995;140:745–754. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Li J, Yuan L, McCouch SR, Tanksley SD. Genetic diversity and its relationship to hybrid performance and heterosis in rice as revealed by PCR-based markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1996;92:637–643. doi: 10.1007/BF00226083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. Developing marker-assisted selection strategies for breeding hybrid rice. Plant Breeding Reviews. 2003;23:73–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Watanabe S, Toda K, Hayashi M, Fuchigami H, Takahashi R, Harada K. Fine mapping of the FT1 locus for soybean flowering time using a residual heterozygous line derived from a recombinant inbred line. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;110:634–639. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1886-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S-H, Cai G-H, Xie F-X, Zhang G-H. Yield analysis of varieties of early indica rice regional test in South China and discussion on breeding. Seed. 1996;81:10–12. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Yang S-H, Cheng B-Y, Shen W-F, Liao X-Y. Progress and strategy of the improvement of indica rice varieties in the Yangtse Valley of China. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 2004;18:89–93. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Yu SB, Li JX, Tan YF, Gao YJ, Li XH, Zhang QF, Saghai Maroof MA. Importance of epistasis as the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L-P. Hybrid rice in China. Chinese Journal of Rice Science. 1986;1:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L-P, Tang C-D. Retrospect, current status and prospect of hybrid rice. Rice in China. 1999;4:3–6. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Zhou ZQ, Yang GP, Xu CG, Liu KD, Saghai Maroof MA. Molecular marker heterozygosity and hybrid performance in indica and japonica rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1996;93:1218–1224. doi: 10.1007/BF00223453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J-Y, Fan Y-Y, Wu J-L Xia Y-W, Zheng K-L. Identification of over-dominance QTL in hybrid rice combinations. Hereditas (Beijing) 2000;22:205–208. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J-Y, Fan Y-Y, Wu J-L, Xia Y-W, Zheng K-L. Importance of over-dominance as the genetic basis of heterosis in rice. Science in China (Series C) 2001;44:327–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02879340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J-Y, Fan Y-Y, Rao Z-M, Wu J-L, Xia Y-W, Zheng K-L. Analysis on additive effects and additive-by-additive epistatic effects of QTLs for yield traits in a recombinant inbred line population of rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;105:1137–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]