Abstract

The structure of the tetrameric K+ channel from Streptomyces lividans in a lipid bilayer environment was studied by polarized attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The channel displays approximately 43% α-helical and 25% β-sheet content. In addition, H/D exchange experiments show that only 43% of the backbone amide protons are exchangeable with solvent. On average, the α-helices are tilted 33° normal to the membrane surface. The results are discussed in relationship to the lactose permease of Escherichia coli, a membrane transport protein.

Ion channels that facilitate selective conduction of K+ ions across cell membranes are involved in an enormous variety of biological processes (1). At the molecular level, K+ channels fall into two broad classes differentiated by transmembrane topology, containing either two or six putative transmembrane α-helical sequences (2). Regardless of subfamily, all K+ channels are tetrameric in architecture and have many common conduction properties. Studies of K+ channels have been limited to the combination of electrophysiological recording and recombinant DNA techniques, largely because of difficulties in purifying sufficient quantities to permit protein-level biochemical approaches.

A prokaryotic K+ channel encoded by the KcsA gene of Streptomyces lividans (3) provides a unique opportunity to overcome these biochemical impediments. The protein product of this gene, the SliK K+ channel, can be expressed at high levels in Escherichia coli membranes and purified in milligram quantities (3–5). The purified protein forms an unusually stable homotetramer and is a fully functional K+ channel (4–7). On the basis of hydrophobicity analysis of its sequence, SliK contains two transmembrane segments, and indeed, previous CD spectra of reconstituted proteoliposomes suggest an α-helical content of 50–60% (4). A more detailed view of membrane proteins is provided by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, which furnishes information about secondary structural elements and also the orientation of α-helices within the lipid bilayer. To obtain a general picture of the secondary structure of a K+ channel, we reconstituted SliK into liposomes and studied it by polarized attenuated total reflection FTIR (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-1-glycerol (POPG) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. SliK protein was expressed in E. coli and purified as described (5). All preparations of SliK were confirmed to be homotetrameric and functional as K+-selective channels (5, 7).

Reconstitution of SliK into Liposomes.

Purified SliK was added at a lipid/protein ratio of 15:1 or 5:1 (wt/wt) into a mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-(1-glycerol) (4:1, mol/mol, ≈10 mM total lipid) solubilized in 16 mM CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane sulfonate; Sigma). Liposomes were formed by running the mixture over a Sephadex G-25 column. The fraction containing the protein was washed twice in 50 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.0 and finally resuspended in the same buffer at 4–5 mg of protein per ml. SDS/PAGE of the protein incorporated into the lipids before and after drying on a germanium (Ge) internal reflection element was performed to verify the tetrameric state of SliK.

IR Spectroscopy.

IR spectra were collected in a Bomem (Quebec) DA3 FTIR spectrometer purged with N2. Typically, interferograms were recorded with 4 cm−1 spectral resolution and processed by using Blackman Harris apodization; 1,000 scans were averaged for one spectrum. A modified continuous flow ATR setup (Janos Technology, Townshend, VT) equipped with a wire grid polarizer (Harrick Scientific, Ossining, NY) was used. The sample (100 μL; ca. 450 μg SliK) was dried on a Ge internal reflection element (25 reflections), and measurements were performed at room temperature using an incident angle of 45°.

H/D Exchange.

Perdeuterated buffers were made by lyophilizing the respective buffer, resuspending in D2O, and adjusting the pD with NaOD or DCl to the desired value (pD = pH + 0.4 pH units). To record the time course of H/D exchange, the sampling cell with the dried protein was filled with 50 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM KCl in H2O at pH 7.0, and several spectra were recorded. Via a peristaltic pump, the H2O buffer was replaced by the deuterated form, and spectra with an increasing number of coadded scans were recorded continuously. To measure the degree of backbone H/D exchange, the integral amide II intensity between 1,565 and 1,525 cm−1 was determined.

Data Analysis.

After data acquisition, an automatic baseline correction of the spectra was performed when needed and spectra were zeroed at 1,950 cm−1. To resolve the overlapping bands in the amide I spectral region for secondary structure and tilt angle determination, the spectra were deconvolved and smoothed by using Bayesian and maximum entropy restoration as provided by razor software (version C3.1, Spectrum Square Associates, Sherburne, NY) for GRAMS/386. Iterations for deconvolution, smoothing, and subsequent band fitting were started by using a Gauss-Lorentz sum peak with a full width at half height (FWHH) of 13 cm−1. For orientational studies, the electrical field amplitudes in the evanescent field, the order parameters of the sample, and the average α-helical tilt angles were calculated as in ref. 8.

RESULTS

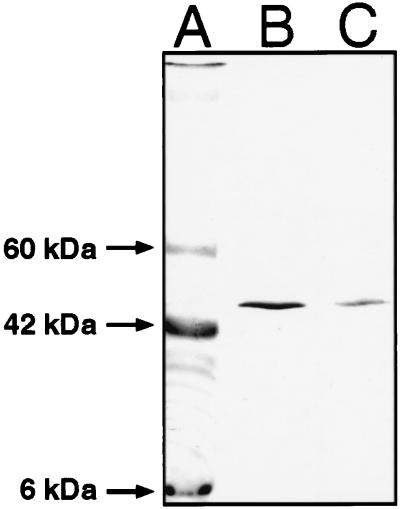

When using spectroscopic methods to examine a protein, it is essential to have confidence that the sample maintains structural and functional integrity. This is a particular concern for integral membrane proteins, which often are plagued by denaturation. The SliK K+ channel is known to be unusually stable in both lipid bilayers and detergent micelles (5), but its stability has not been assessed under conditions required for FTIR spectroscopy, namely after drying proteolipid films on the surface of a Ge crystal. We therefore assayed the oligomeric state of SliK, exploiting the finding (5) that the functional homotetramer migrates at ≈50 kDa on SDS/PAGE, whereas the denatured monomer runs at 18 kDa. Fig. 1 shows that even after drying on Ge, SliK remains in its tetrameric form.

Figure 1.

Stability of SliK tetramer. Samples of SliK were run on SDS/PAGE after the following treatments. Lane A: Protein standard. Lane B: 10 μg SliK reconstituted into liposomes at a lipid/protein ratio of 5:1. Lane C: The same sample as in lane B after drying on the Ge internal reflection element and resuspending into 50 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.0.

Secondary Structure.

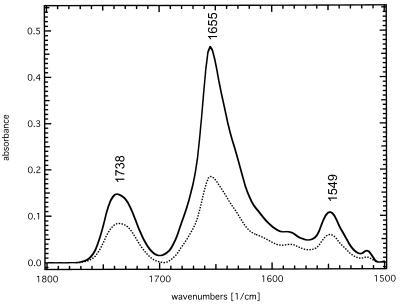

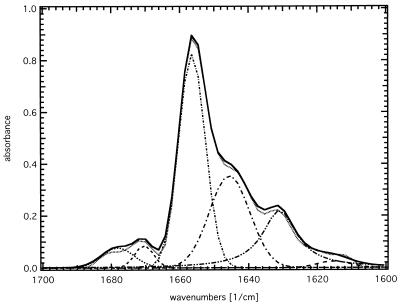

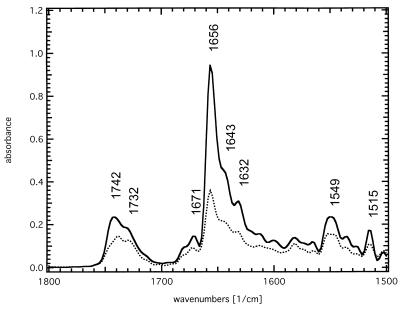

The ATR-FTIR absorbance spectrum of SliK dried from deuterated buffer (Fig. 2) is dominated by the bands of the lipid ester C=O stretching mode at 1,738 cm−1, the absorption of the amide I envelope at 1,655 cm−1, and the amide II band at 1,549 cm−1. The absorption maximum of the amide I band immediately indicates a dominant α-helical contribution; however, a quantitative assignment of the individual secondary structure elements is possible only after deconvolution and subsequent band fitting of the spectrum, as shown in Fig. 3. The individual components are integrated over the total amide I absorption between 1,700 and 1,600 cm−1 to give the relative secondary structure contents. Five significant bands are detected with absorption maxima at 1,678 cm−1 and 1,670 cm−1, (5–10%, turns), 1,656 cm−1 (43%, α-helix), 1,645 cm−1 (28%, random coil), and 1,631 cm−1 (20–25%, β-sheet) (9–12).

Figure 2.

Polarized ATR-FTIR absorbance spectra of SliK. The sample with a lipid/protein ratio of 5:1 was dried from deuterated phosphate buffer at pD 7.0. The dominant bands are the lipid ester C=O stretching vibration at 1,738 cm−1, the amide I envelope at 1,655 cm−1, and the remaining amide II band at 1,549 cm−1. Solid line: parallel polarized light; dotted line: perpendicular polarized light.

Figure 3.

Deconvolution and band fitting of the amide I band. For secondary structure determination the amide I band, as recorded with parallel polarized light in Fig. 2, was deconvolved and fitted with five spectral components (dashed lines). The deconvolved bands are assigned to relative contents of turns (5–10%), α-helix (43%), random coil (28%), and β-sheet (20–25%), as described in the text.

H/D Exchange.

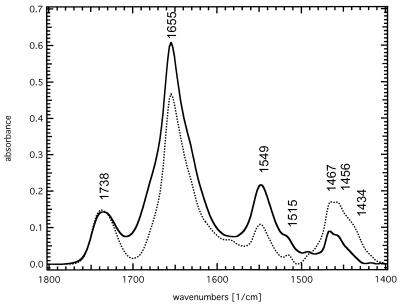

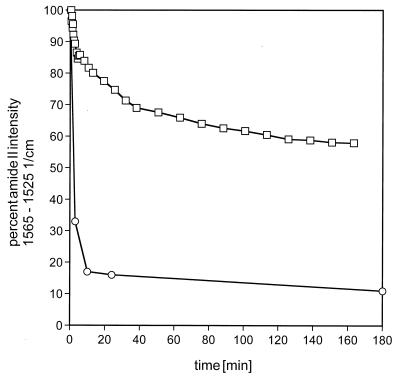

The solvent accessibility of SliK can be gauged by the kinetics of amide proton exchange. To follow this process, we dried a sample from H2O buffer onto the crystal surface and collected an initial spectrum (Fig. 4, solid line); H2O buffer was then substituted with D2O buffer, and spectra were taken at various time intervals, until exchange was complete (Fig. 4, dotted line). The amide II vibration at 1,549 cm−1 in H2O buffer is indicative of the peptide-NH-bending mode and therefore is useful to monitor the degree of H/D exchange. In D2O this mode shifts onto the lipid methylene scissoring mode at 1,467 and 1,456 cm−1 with a shoulder at 1,434 cm−1. The decrease in the intensity of the 1,549 cm−1 band (integrated between 1,565 and 1,525 cm−1) reflects ≈45% of the protein backbone amide protons undergoing H/D exchange. The remaining absorption at 1,549 cm−1 in D2O represents peptide groups that are inaccessible to bulk water. The time course of the H/D exchange reaction is shown in Fig. 5. Proton exchange occurs with multiple kinetic components, with 10–15% exchanging rapidly, and the remaining exchangeable protons (30–35% of the total) displaying a time constant on the order of 1 hr. Compared with SliK the lactose permease of E. coli shows a dramatically faster H/D exchange of 80–90% within 10–20 min, reaching 95% completion after 24 hr (see also ref. 8).

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR absorbance spectra of SliK dried from H2O and D2O. Both spectra were recorded on the same sample dried from H2O buffer (solid line) and, after completed exchange, from D2O buffer (dotted line).

Figure 5.

Time course of H/D exchange for SliK and the lactose permease. The integral intensity of the amide II band between 1,565 and 1,525 cm−1 was monitored as a function of time after switching to D2O buffer. □ : SliK; ○ : Lactose permease. To overcome the weak amide II signal of the lactose permease sample with a lipid-to-protein ratio of 10:1 (wt/wt) in the liquid D2O phase, the sample was dried and measured at the given time points.

Orientation of SliK in the Membrane.

The polarized ATR-FTIR spectra of Fig. 2 can be deconvolved to determine the average α-helical tilt angle and insertion of the protein into the membrane (Fig. 6). The separate α-helical contributions in the amide I region with an absorption maximum at 1,656 cm−1 yield a dichroic ratio RATR of 2.995. Using thick film approximation, this value reflects an order parameter S = 0.552 and an average α-helical tilt angle in the membrane of 33°. The same tilt angle was obtained at two different lipid to protein ratios [5:1 (wt/wt) and 15:1 (wt/wt); data not shown]. This invariance points to a rigid assembly of SliK within the membrane, in marked contrast to the conformationally active and flexible lactose permease from E. coli, where changes in protein packing density give rise to different α-helical tilt angles (8).

Figure 6.

Polarized ATR-FTIR absorbance spectra after deconvolution. The α-helical component of the amide I band at 1,656 with a dichroic ratio RATR = 2.995 results in an order parameter S = 0.552 and an average α-helical tilt angle of 33° with respect to the membrane normal. Solid line: parallel polarized light, dotted line: perpendicular polarized light. Compare with Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here confirm the basic features of SliK secondary structure that are expected from the protein’s primary sequence and the known molecular properties of SliK and other K+ channels. Each SliK subunit is a 161-residue polypeptide with two putative transmembrane α-helices (containing ≈50 residues) identified on the basis of hydrophobicity. In addition, on the basis of its sequence similarity to the P-region of the Shaker K+ channel, we anticipate that SLiK contains a three-turn α-helix in its pore-forming region (13, 14). Assuming that these are the only α-helical regions of SliK, a helical content of 37% would be predicted, in remarkably good agreement with the 43% determined here. Our estimates are lower than the 50–60% helical content determined by CD measurements (4), but because light scattering from liposomes can undermine CD-based estimates of transmembrane helices, we consider that the FTIR values more accurately reflect the secondary structure composition of SliK (15).

Our results show that 55% of the backbone amide protons of SliK are not exchangeable with solvent on our experimental time scale (3 hr). In this respect, SliK is reminiscent of bacteriorhodopsin, or EmrE, two other unusually stable membrane proteins, in which most of the amide protons are nonexchangeable (16, 17). In contrast, more than 90% of the backbone amide protons of lactose permease exchange readily with solvent (8), as might be expected for a membrane transporter whose very function demands conformational flexibility. The comparison with lactose permease suggests that SliK is a rather rigid protein that does not engage in major conformational rearrangements associated with K+ transport. This suggestion is corroborated by our finding that in SliK, the average helix tilt angle is independent of protein packing density, again in sharp contrast to the behavior of lactose permease (8). It is also an intriguing observation that the fraction of residues in the N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic “tails” of SliK (47%) is similar to the fraction of exchangeable protons determined here (45%).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of Dr. Adrian Gross with the incorporation of SliK into the lipids and the help of Jenny C. Lee with purification of lactose permease. J. le C. is the recipient of a Human Frontier Science Program long-term fellowship, and L.H. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-31768. In addition, the research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1DK51131-01 (H.R.K.).

ABBREVIATION

- ATR-FTIR

attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared

Note Added in Proof

In the course of publication of this paper, a x-ray structure of SliK was reported (18). Our data are in harmony with this structure.

References

- 1.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Nature (London) 1994;371:119–122. doi: 10.1038/371119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrempf H, Schmidt O, Kummerlin R, Hinnah S, Muller D, Betzler M, Steinkamp T, Wagner R. EMBO J. 1995;14:5170–5178. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes D M, Perozo E. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10343–10352. doi: 10.1021/bi971018y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heginbotham L, Odessey E, Miller C. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10335–10342. doi: 10.1021/bi970988i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuello L G, Romero J G, Cortes D M, Perozo E. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3229–3236. doi: 10.1021/bi972997x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heginbotham, L., Kolmakova-Partensky, L. & Miller, C. (1998) J. Gen. Physiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.le Coutre J, Narasimhan L R, Patel C K, Kaback H R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10167–10171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Adv Protein Chem. 1986;38:181–364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goormaghtigh E, Cabiaux V, Ruysschaert J M. Subcell Biochem. 1994;23:329–362. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1863-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goormaghtigh E, Cabiaux V, Ruysschaert J M. Subcell Biochem. 1994;23:405–450. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1863-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byler D M, Susi H. Biopolymers. 1986;25:469–487. doi: 10.1002/bip.360250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Q, Miller C. Science. 1995;268:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.7716526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross A, MacKinnon R. Neuron. 1996;16:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatulian S A, Cortes D M, Perozo E. Biophys J. 1998;74:A205. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00091-x. (abstr.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downer N W, Bruchman T J, Hazzard J H. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:3640–3647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arkin I T, Russ W P, Lebendiker M, Schuldiner S. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7233–7238. doi: 10.1021/bi960094i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyle D A, Cabral J M, Pfuetzner R A, Kuo A, Gulbis J M, Cohen S L, Chait B T, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]