Abstract

High throughput screening and other techniques commonly used to identify lead candidates for drug development usually yield compounds with binding affinities to their intended targets in the mid-micromolar range. The affinity of these molecules needs to be improved by several orders of magnitude before they become viable drug candidates. Traditionally, this task has been accomplished by establishing structure activity relationships (SAR) in order to guide chemical modifications and improve the binding affinity of the compounds. Since the binding affinity is a function of two quantities, the binding enthalpy and the binding entropy, it is evident that a more efficient optimization would be accomplished if both quantities were considered and improved simultaneously. Here, an optimization algorithm based upon enthalpic and entropic information generated by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is presented.

Keywords: Binding Affinity, Enthalpy, Entropy, Thermodynamic Optimization, Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

High throughput screening or fragment screening usually produce hits with binding affinities in the mid micromolar or weaker range. The affinity optimization of a molecule characterized by a dissociation constant (Kd) in the mid-micromolar range all the way to the nanomolar or subnanomolar range, requires an improvement in the Gibbs energy of binding (ΔG = −RTln(1/Kd)) of −6.5 to −8 kcal/mol. Since the Gibbs energy is a function of two quantities, the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) changes, ΔG = ΔH − TΔS, it follows that the optimization goal would be more easily achieved if the enthalpy and entropy changes could be improved simultaneously. Furthermore, extremely high affinities cannot be achieved unless the enthalpy and entropy changes contribute favorably to binding (1–9).

Previously, it has been observed that the binding enthalpy is more difficult to optimize than the binding entropy (10). For example, most first generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors were characterized by unfavorable binding enthalpies (11, 12) that reduced their binding affinity and, in some cases, introduced constraints that hampered their drug resistance profiles. Also, a progression towards a more favorable enthalpy has been observed for the statins as their binding potency has improved (2). It must be remembered that every 1.36 kcal/mol of unfavorable enthalpy, coupled with no change in entropy, lowers the binding affinity by one order of magnitude. Furthermore, an improvement in binding enthalpy does not necessarily results in an improvement in binding affinity since the more favorable binding enthalpy can be compensated by a loss in binding entropy (13). At the thermodynamic level, improving the binding affinity of a lead compound necessarily implies overcoming enthalpy/entropy compensation. If enthalpy changes were always compensated by entropy changes and vice versa, affinity improvements would be impossible.

The optimization of drug candidates would be greatly accelerated if enthalpy and entropy correlations associated with chemical modifications in different regions of the lead molecule were known. In this paper a thermodynamic algorithm for affinity optimization is presented. Based upon experimental data obtained by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), this approach allows the identification of lead molecule regions and the type of chemical functionalities that will improve the binding affinity by simultaneously optimizing binding enthalpy and binding entropy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

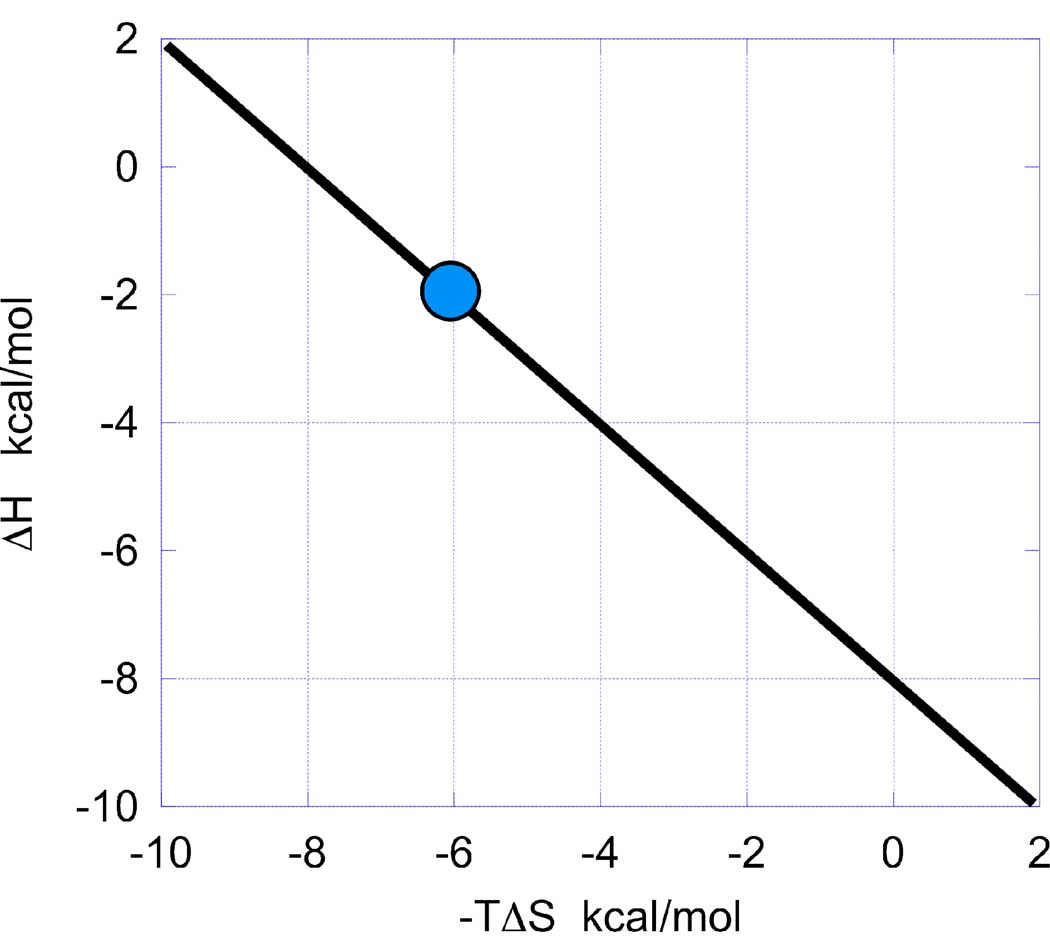

As soon as a candidate for optimization is identified and characterized calorimetrically (i.e. its binding affinity, binding enthalpy and binding entropy are known), a thermodynamic optimization plot (TOP) can be constructed. This plot (Figure 1) is defined by setting as ordinate the binding enthalpy (ΔH) and as abscissa the entropy contribution to affinity (−TΔS). A straight line (optimization line) is drawn between the experimental (−TΔS, ΔH) point and the point (0, ΔG). The point (0, ΔG) is obtained by considering that when −TΔS = 0, ΔH = ΔG. The resulting thermodynamic optimization plot has a slope of −1, it is built with a single experimental point corresponding to the binding thermodynamics of the lead compound and should not be confused with so-called “enthalpy/entropy compensation” plots. Enthalpy/entropy compensation plots are built by plotting enthalpy and entropy values for many compounds and then performing a linear least squares fit of the data (14, 15). The thermodynamic optimization plot, as defined here, provides a platform for lead optimization based upon the binding thermodynamics of the lead compound.

Figure 1.

The thermodynamic optimization plot is constructed by setting as ordinate the binding enthalpy (ΔH) and as abscissa the entropy contribution to affinity (−TΔS). The coordinates of the selected compound for optimization are plotted (blue point) and a straight line is traced between that point and (0, ΔG). The point (0, ΔG) is obtained by considering that when −TΔS = 0, ΔH = ΔG. The resulting graph defines the thermodynamic platform for lead optimization.

Thermodynamic Optimization Plot

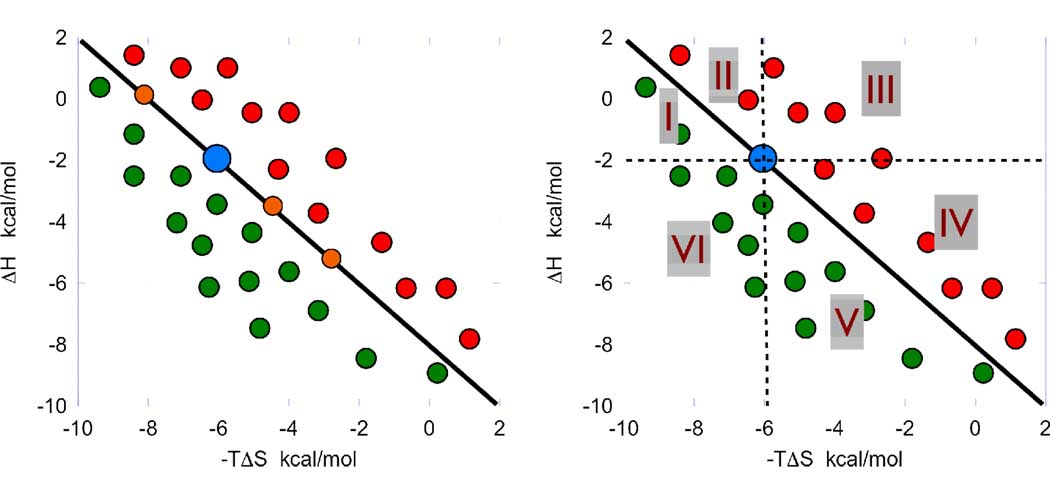

In a drug development setting, the lead candidate is modified in different ways and the resulting compounds analyzed for binding activity. Once a first round of chemical modifications has been made, the binding thermodynamics of the resulting compounds are measured by ITC. Their measured ΔH and −TΔS values are added to the thermodynamic optimization plot as shown in Figure 2 (left panel). In this plot, all points that fall onto the optimization line defined in Figure 1 have the same Gibbs energy (ΔG) and correspondingly the same binding affinity as the lead compound. Likewise, all points that fall above the optimization line have a lower binding affinity (more positive ΔG), and all points that fall below the optimization line have a higher binding affinity (more negative ΔG). Since the slope of the optimization line is −1, it follows that, for any given compound in the graph, the actual change in ΔG relative to the lead compound is given by either the vertical or horizontal distance from the coordinates of the compound to the optimization line. In a traditional SAR analysis, the affinity data provides all the information for subsequent rounds of optimization. The thermodynamic optimization plot provides two additional dimensions and much richer information as shown in Figure 2 (right panel).

Figure 2.

After a round of optimization, the (−TΔS, ΔH) points for all compounds are plotted. Compounds with better affinity (shown in green) fall below the optimization line while compounds with lower affinity (shown in red) fall above the optimization line. Compounds with the same affinity as the parent compound (shown in orange) fall on the optimization line. By tracing a vertical and horizontal line through the coordinates of the parent compound, six different regions can be defined. These regions define distinct strategies for optimization as described in the text.

Different Regions in Thermodynamic Optimization Plot

In Figure 2 (right panel) six different regions have been defined by tracing a vertical and a horizontal line through the experimental (−TΔS, ΔH) point for the lead compound. These regions are characterized not only by a higher or lower binding affinity but, most importantly, by different enthalpic and entropic contributions to affinity. Since each region can be mapped into a specific compound modification, it is possible to identify the location and the type of chemical functionalities that will maximize a favorable enthalpy and entropy of binding.

Regions I and II in Figure 2 define the regions in which the binding entropy is more favorable but the binding enthalpy is less favorable. The difference between region I and II is that in region I, the entropy gain is stronger than the enthalpy loss, resulting in a gain in binding affinity. Region III is the region where modifications result in both enthalpy and entropy losses. Compounds that fall in region III contain modifications that should not be repeated in further rounds of optimization. Those functionalities are better maintained the way they are in the original compound or replaced by functionality classes not yet considered. In region IV the binding enthalpy is actually more favorable, but not sufficient to overcome the associated entropy loss. In regions V and VI, the modifications to the compound result in a stronger binding affinity. In region V, the enthalpy gains are able to overcome any compensating entropy losses while in region VI both the enthalpy and entropy changes are improved. From the point of view of improving binding affinity, region VI represents the best possible situation since compounds that fall in this region have better enthalpy and better entropy. There could be situations in which binding affinity is not everything and that better selectivity or drug resistant profiles require a bias towards stronger enthalpic or entropic contributions to affinity (10, 12). The optimization plot also provides the required information in those cases. Essentially the thermodynamic optimization plot permits a structural mapping of the enthalpic and entropic consequences of chemical modifications to a compound.

Further Optimization

Regions I, V and VI identify modifications that result in better binding affinities and can be additionally explored with additional functionalities in order to expand the gains. Regions II and IV, on the other hand, are particularly important for subsequent optimization rounds, since these regions show enthalpy or entropy gains that are overcompensated by opposite entropy or enthalpy losses. In region II, the binding entropy is improved but the binding affinity diminishes due to a larger enthalpy loss. Conversely, in region IV the binding enthalpy is improved but the binding affinity diminishes due to a larger entropy loss. In both cases the issues facing the drug designer are comparable: How to maintain the entropy or enthalpy gains while minimizing the enthalpy or entropy losses, respectively?

Enthalpy/Entropy Compensation

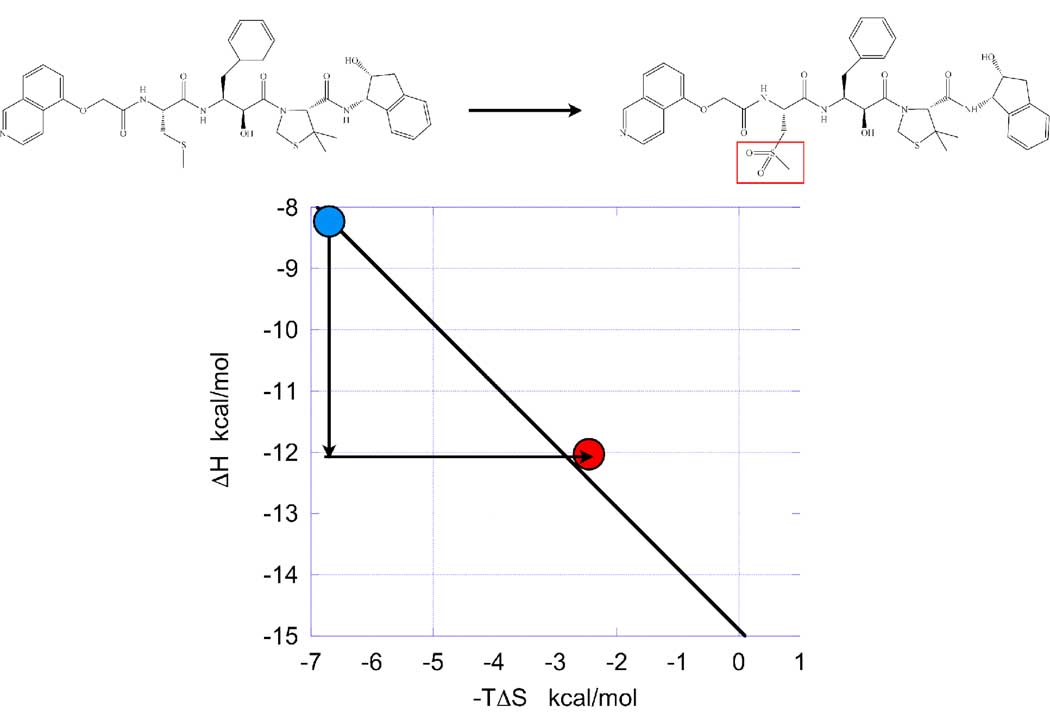

During affinity optimization different enthalpy/entropy responses to compound modifications are encountered and have been reported by different laboratories (see for example references (3, 4, 9, 13, 16–18)). Figure 3 illustrates one of the most common situations observed during optimization. The figure shows a high affinity HIV-1 protease inhibitor (KNI-10033) and the results obtained by adding a sulfonamide hydrogen bonding functionality (KNI-10075). The addition of the sulfonamide group results in an enthalpy gain of −3.9 kcal/mol, which is completely compensated by an entropy loss, resulting in a slight decrease in affinity (13). The data for this example was presented by Lafont et al (13), who also explored the structural origin of the thermodynamic changes by x-ray crystallography. The improvement in binding enthalpy was traced to the additional hydrogen bond between one sulfonamide oxygen in the inhibitor and the amide nitrogen in Asp 30B of the HIV-1 protease. No other changes in hydrogen bonding or conformation were present in the crystal structures. The entropy loss, on the other hand, was attributed to the combination of two factors, a loss of conformational entropy due to the structuring of the protease region around the new hydrogen bond, and a smaller desolvation entropy due to a higher solvent exposure of hydrophobic groups in the protein/inhibitor complex.

Figure 3.

A typical situation encountered during affinity optimization. The addition of a hydrogen bonding functionality results in a strong enthalpy gain which is compensated by an equally large entropy loss. In this particular example the entropy loss is actually larger than the enthalpy gain and the new compound loses binding affinity (region IV). The enthalpic (ΔH) gain is given by the vertical arrow and the entropic (−TΔS) loss by the horizontal arrow. The change in ΔG of the new compound (red point) relative to the initial compound (blue point) is given by either the horizontal or vertical distance of the new compound coordinates (red point) to the optimization line. Data from reference (13).

In our experience, strong hydrogen bonds contribute on the order of −4 – −5 kcal/mol to the binding enthalpy (10, 13); however in many cases, as the one shown in Figure 3, the enthalpic gain is opposed by large entropic losses. Under those conditions, gaining binding affinity requires overcoming the entropic compensation associated with the enthalpic gain. Strategies proposed to minimize the entropic compensation involve targeting already structured regions of the protein such that the loss of conformational entropy is significantly reduced; targeting several hydrogen bonds to the same protein group such that “only one” pays the conformational penalty; and, selecting a stereochemistry that lowers the solvent exposure of hydrophobic groups and minimizes desolvation entropy losses. If successful, any or more of these strategies should be able to defeat enthalpy/entropy compensation, rescue a compound from region IV, bring it to region V and consequently improve its binding affinity.

Overcoming Enthalpy/Entropy Compensation

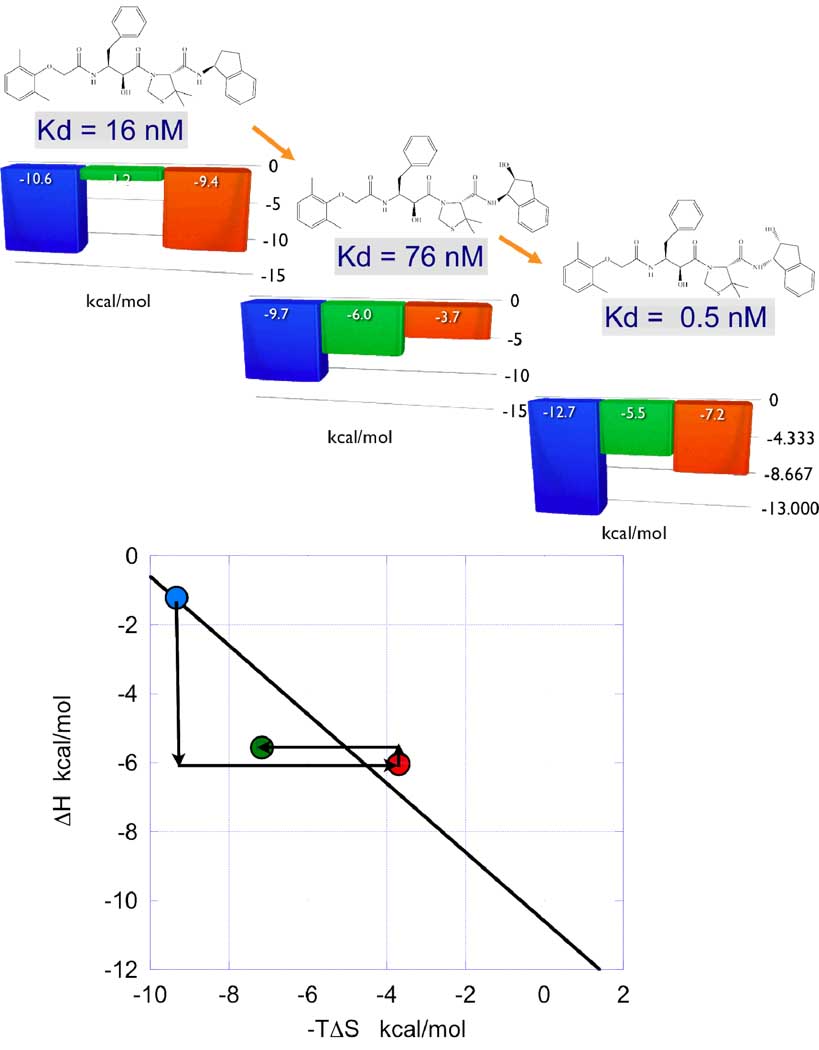

Compounds in region IV exhibit binding enthalpy gains that are compensated by entropy losses, resulting in weaker binding affinities. These compounds could be rescued from region IV if the entropy losses can be reduced while maintaining the enthalpy gains. Figure 4 illustrates a situation encountered during the optimization of inhibitors of plasmepsin II, an aspartic protease validated as an antimalarial target (19). In panel A (left) the thermodynamic signature of the parent compound (KNI-10026) is indicated. Addition of a hydroxyl group (KNI-10007, center) results in a loss in binding affinity despite a large enthalpy gain of −4.8 kcal/mol. The loss in binding affinity originates from a large entropy loss that more than compensates the enthalpy gain. The large enthalpy gain is consistent with the formation of a strong hydrogen bond by the hydroxyl group. Changing the stereochemistry of the parent compound yields a new compound (KNI-10006) that maintains the enthalpy gain without incurring a significant entropy loss. As a result, the binding affinity of the lead compound is improved from 16 nM to 0.5 nM. This example illustrates a case in which enthalpy/entropy compensation is defeated and the compound is recued from region IV and relocated into region V by a change in stereochemistry. The stereochemistry change most likely results in the additional burial of hydrophobic atoms within the binding pocket and an increased desolvation entropy; i.e. a larger release of buried waters. It is apparent that considerations for the engineering of hydrogen bonds should involve more than atomic distances and angles. They should involve a consideration of the degree of structuring of the target atom and that the bound conformation does not impair the burial of neighboring groups from solvent. The thermodynamic optimization plot permits the experimental identification of the location and type of compound modification that allows overcoming enthalpy/entropy compensation.

Figure 4.

Regions II and IV identify compound modifications that result in enthalpy or entropy gains but are overcompensated but opposite entropy or enthalpy losses, resulting in a net affinity loss. These regions provide unique opportunities for affinity improvement by minimizing the compensating changes. In this figure, the addition of a hydrogen bond functionality to a plasmepsin II inhibitor improves the binding enthalpy but triggers a larger entropic loss. A change in the stereochemistry of the compound maintains the enthalpy gain but minimizes the entropy loss resulting in a significant affinity gain. In the top panel, the thermodynamic signatures of the three compounds are shown; in this panel the blue bars denote ΔG, the green bars ΔH and the red bars −TΔS. In the bottom panel the thermodynamic optimization plot is shown. Data from reference (19).

CONCLUSIONS

For several years, the idea of utilizing ITC data in lead optimization strategies has been considered extremely desirable but its incorporation into practical protocols has been difficult. The thermodynamic optimization plot presented here provides a platform that allows classification of modified compounds into six different regions characterized by different enthalpy/entropy profiles. Compounds that fall into any of these regions can be further ranked in terms of their enthalpic and entropic gains, thus providing a precise map of the localization and type of modifications that maximize the enthalpy and entropy of binding. The combination of those modifications into subsequent rounds is expected to accelerate binding affinity optimization.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Arne Schön for reading the manuscript and for many helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM56550 and GM57144) and the National Science Foundation (MCB0641252).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohtaka H, Freire E. Adaptive Inhibitors of the HIV-1 protease. Progr Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;88:193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbonell T, Freire E. Binding thermodynamics of statins to HMG-CoA reductase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11741–11748. doi: 10.1021/bi050905v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruben AJ, Kiso Y, Freire E. Overcoming roadblocks in lead optimization: a thermodynamic perspective. Chemical biology & drug design. 2006;67:2–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarver RW, Peevers J, Cody WL, Ciske FL, Dyer J, Emerson SD, et al. Binding thermodynamics of substituted diaminopyrimidine renin inhibitors. Anal Biochem. 2007;360:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaires JB. Calorimetry and Thermodynamics in Drug Design. Ann Rev Biophys. 2008;37:135–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schon A, Madani N, Klein JC, Hubicki A, Ng D, Yang X, et al. Thermodynamics of binding of a low-molecular-weight CD4 mimetic to HIV-1 gp120. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10973–10980. doi: 10.1021/bi061193r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ababou A, Ladbury JE. Survey of the year 2005: literature on applications of isothermal titration calorimetry. J Mol Recognit. 2007;20:4–14. doi: 10.1002/jmr.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muralidhara BK, Halpert JR. Thermodynamics of ligand binding to P450 2B4 and P450eryF studied by isothermal titration calorimetry. Drug metabolism reviews. 2007;39:539–556. doi: 10.1080/03602530701498182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarver RW, Bills E, Bolton G, Bratton LD, Caspers NL, Dunbar JB, et al. Thermodynamic and structure guided design of statin based inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. J Med Chem. 2008;51:3804–3813. doi: 10.1021/jm7015057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freire E. Do enthalpy and entropy distinguish first in class from best in class? Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velazquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Freire E. The binding energetics of first- and second-generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors: implications for drug design. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;390:169–175. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vega S, Kang LW, Velazquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Amzel LM, Freire E. A structural and thermodynamic escape mechanism from a drug resistant mutation of the HIV-1 protease. Proteins. 2004;55:594–602. doi: 10.1002/prot.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafont V, Armstrong AA, Ohtaka H, Kiso Y, Mario Amzel L, Freire E. Compensating enthalpic and entropic changes hinder binding affinity optimization. Chemical biology & drug design. 2007;69:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Dantzer JJ, Nowacki J, O'Callaghan BJ, Meroueh SO. PDBcal: a comprehensive dataset for receptor-ligand interactions with three-dimensional structures and binding thermodynamics from isothermal titration calorimetry. Chemical biology & drug design. 2008;71:529–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson TS, Williams MA, Pitt WR, Ladbury JE. The thermodynamics of protein-ligand interaction and solvation: insights for ligand design. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;384:1002–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czodrowski P, Sotriffer CA, Klebe G. Protonation changes upon ligand binding to trypsin and thrombin: structural interpretation based on pK(a) calculations and ITC experiments. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;367:1347–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JD, Gilbert PJ, Williams MA, Pitt WR, Ladbury JE. Identification of novel fragment compounds targeted against the pY pocket of v-Src SH2 by computational and NMR screening and thermodynamic evaluation. Proteins. 2007;67:981–990. doi: 10.1002/prot.21369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruben AJ. Adaptive Plasmepsin Inhibitors as Novel Antimalarials. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 2008. Adaptive Plasmepsin Inhibitors as Novel Antimalarials. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nezami A, Kimura T, Hidaka K, Kiso A, Liu J, Kiso Y, et al. High-affinity inhibition of a family of Plasmodium falciparum proteases by a designed adaptive inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8459–8464. doi: 10.1021/bi034131z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]