Abstract

Objective To determine whether collaborative requesting increases consent for organ donation from the relatives of patients declared dead by criteria for brain stem death.

Design Unblinded multicentre randomised controlled trial using a sequential design. Centralised 24 hour telephone randomisation based on randomised permuted blocks of 10.

Setting 79 general, neuroscience, and paediatric intensive care units in the United Kingdom.

Participants 201 relatives of patients meeting criteria for brain stem death. Relatives were blind to the intervention and to the trial; all other participants were necessarily unblinded.

Interventions Collaborative requesting for consent for organ donation by the potential donor’s clinician and a donor transplant coordinator (organ procurement officer) compared with routine requesting by the clinical team alone.

Main outcome measure Proportion of relatives consenting to organ donation.

Results 101 relatives were randomised to routine requesting and 100 to collaborative requesting. All were analysed on an intention to treat basis. In the routine requesting group, 62 relatives consented to organ donation. In the collaborative requesting group, 57 relatives consented. After correction for the ethnicity, age, and sex of the potential donors the risk adjusted ratio of the odds of consent in the collaborative requesting group relative to the routine group was 0.80 (95% confidence interval 0.43 to 1.53), with a P value of 0.49 adjusted for interim analysis and trial over-running. The conversion rate (donors with consent from whom any organs were retrieved) was 92% (57/62) in the routine requesting group and 79% (45/57) in the collaborative requesting group (P=0.043). There were 140 approaches to relatives in the per protocol analysis, leading to 60.3% (44/73) consent after routine and 67.2% (45/67) after collaborative requesting (risk adjusted odds ratio of consent 1.47, 0.67 to 3.20, P=0.33).

Conclusion There is no increase in consent rates for organ donation when collaborative requesting is used in place of routine requesting by the patient’s clinician.

Trial registration ISRCTN01169903

Introduction

The most common reason why organs for transplantation are not obtained from patients after confirmation of brain stem death on an intensive care unit in the United Kingdom is the refusal of consent by the patient’s relatives. A recent audit of all deaths in 341 intensive care units in the UK over a 24 month period showed that 41% of the relatives of potential organ donors denied consent for donation.1 Although in the UK the Human Tissue Act 2004 prioritises the wishes and consent of the potential organ donor over his or her relatives, it is almost inconceivable that organs would be retrieved from a deceased donor against the wishes of relatives. Consent for donation is therefore likely to remain an important step in organ procurement for the foreseeable future.

About a third of the relatives of patients declared dead by brain stem criteria who refused donation, when interviewed subsequently suggested they would not make the same decision again, whereas few consenting relatives regretted their decision, suggesting that many refusals are not based on deeply held views.2 3 There might therefore be factors in the way the request for donation is made that could affect the decision. A recent systematic review identified 11 observational studies suggesting that using trained and experienced individuals to make requests for organ donation increased consent rates.4 One technique to maximise the experience of requestors is “collaborative requesting,” where a request for organ donation is made jointly by the patient’s clinician and a donor transplant coordinator (often referred to as an organ procurement officer outside the UK). Although widely advocated, the efficacy or effectiveness of this technique has not been rigorously tested.

Methods

The ACRE (Assessment of Collaborative REquesting) study was designed to test the null hypothesis that there is no difference in consent rates for organ donation when relatives are approached by the clinical team and a donor transplant coordinator together (collaborative request) compared with the clinical team alone (routine request). The study was an unblinded multicentre randomised controlled trial, with a sequential design.

Participants were the relatives of patients declared dead by criteria for brain stem death or awaiting brain stem death testing who were to be approached regarding organ donation. The study took place in 79 general, neuroscience, and paediatric intensive care units in the UK. We excluded units with in house donor transplant coordinators and a collaborative requesting rate over 50% when the study started.

Our primary outcome measure was the proportion of relatives giving consent to organ donation. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of potential donors from whom each type of solid organ was retrieved and transplanted, and the proportion from whom tissues were retrieved.

The duty office of NHS Blood and Transplant in Bristol provided a telephone based randomisation service with allocation to either collaborative or routine requesting, based on randomised permuted blocks of 10. Randomisation was made at the time when the patient’s clinicians and the donor transplant coordinator agreed to request organ donation from the relatives of a patient declared dead by brain stem criteria. The donor transplant coordinator collected data on the donor and relatives; the National Transplant Database maintained by NHS Blood and Transplant provided data on organ procurement and use.

We could not obtain consent for this study from relatives as the consenting process would reveal the outcome of brain stem death tests and would influence their subsequent response to requests for organ donation. We obtained a waiver of the requirement for consent for the trial from a multicentre research ethics committee. Thus the relatives were blind both to the intervention and to the trial itself; all other participants were necessarily unblinded.

There is no universally accepted definition of collaborative requesting nor a clear consensus in the UK.5 In the context of this trial, collaborative requesting required that a patient’s clinician and a donor transplant coordinator both took part in the interview with family members when a request for organ donation was made. This ensured that the expertise of the donor transplant coordinator was available at the time the request was made. The clinicians and coordinators were required to discuss their respective roles in the interview in advance, but these roles were not prescribed. They were allowed to decide whether to request organ donation during the interview when the results of the brain stem death tests were discussed or whether to request organ donation in a subsequent interview (“decoupling” the request).

Our primary end point (consent for organ donation) was determined soon after randomisation, and because of the shortage of organs for transplantation there was a practical and ethical requirement not to prolong the study if a clear difference in consent rates became apparent. Consequently we used a sequential design and analysed the data using a triangular test.6 In this design, the extent of the difference between the consent rates in the two groups is examined after the first 100 patients have been recruited, and subsequently every 50, until there is evidence that the two rates differ or that there is no difference between them. The sequential analysis of the study was carried out with PEST (planning and evaluation of sequential trials) software.7 A consent rate of 60% was anticipated for routine requesting, with an expected increase to 75% for collaborative requesting.8 The boundaries of the sequential design were set so that if collaborative requesting was superior, there was a 90% probability of showing this with a 5% significance level. The design properties indicated an expected sample size of 195 relatives, under the hypothesis of no difference in consent rates, with a 10% chance that more than 293 would be needed. The expected sample size in the presence of a 15% increase in the consent rate was 254, with a 10% chance that more than 386 relatives would be required. For the equivalent fixed sample size study, we would have needed 400 relatives to detect a difference in consent rates of 15% as significant at the 5% level with 90% power.

The results were analysed primarily on an intention to treat basis (all randomised relatives). Interim analyses were adjusted for the age group of the patient (0-17, 18-24, 25-34, 35-49, 50-59, ≥60), ethnicity (white, non-white), and sex, factors that might influence the consent rate for organ donation.1 9 We used the “Christmas tree” correction to adjust for the discrete monitoring and adjusted the final P value for the treatment difference to account for over-running.6 A per protocol analysis was also undertaken on those relatives who had a collaborative request. Predefined secondary outcome measures were the total number of solid organs retrieved, both overall and by type, and the proportion of brain stem dead organ donors for whom relatives had consented for donation of any solid organ who actually donated any organs (the “conversion rate”).

Results

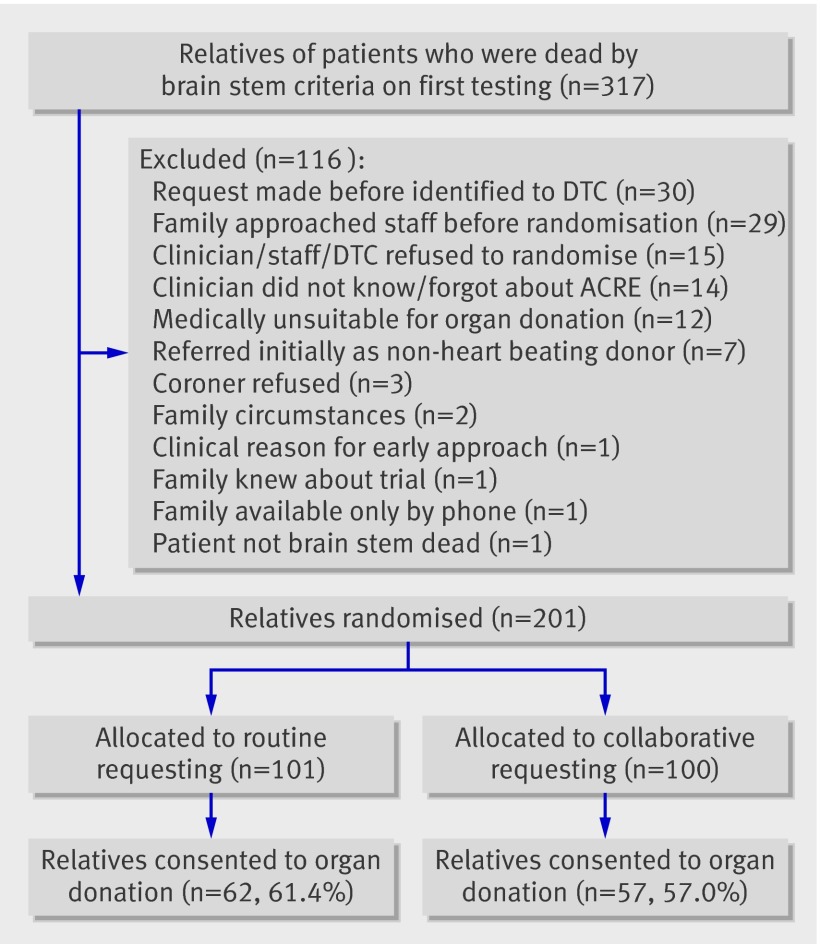

Figure 1 shows the flow of relatives in the study. The proportion of relatives consenting to organ donation is based on the allocated approach (intention to treat). The study recruited relatives between December 2007 and October 2008.

Fig 1 Flow of relatives through trial

Tables 1-3 give the demographics of the potential donors (patients), the relatives, and the requestors. There were no differences in characteristics of donors between the study groups, and the relatives were matched, except that there were fewer parents of donors and more children of donors in the collaborative requesting group and more patients who were registered with the UK organ donor registry or whose views on organ donation were known in the routine requesting group. The characteristics of the requestors were matched. As is standard practice in most UK intensive care units, the potential donor’s nurse was present at most (88.2%) of the interviews.

Table 1.

Characteristics of potential donors

| All (n=201) | Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age (years)* | 47.4 (34.2-58.1) | 43.3 (31.8-54.8) | 48.8 (37.6-60.6) |

| No (%) below age 18* | 13 (6.5) | 7 | 6 |

| Sex male (%)* | 103 (51.5) | 55 | 48 |

| Ethnicity (%)†: | |||

| White | 180 (91.8) | 91 | 89 |

| Asian/Asian British | 7 (3.6) | 3 | 4 |

| Black/Black British | 6 (3.1) | 5 | 1 |

| Chinese/oriental | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 2 |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 |

| Cause of death (%)‡: | |||

| Trauma | 45 (23.2) | 23 | 22 |

| Non-trauma | 149 (76.8) | 74 | 75 |

| On UK organ donor register (%)§ | 31 (15.7) | 18 | 13 |

| Not on register but known to have given verbal or written consent to organ donation (%)¶ | 25 (15.0) | 15 | 10 |

IQR=interquartile range.

*Missing for 1 patient in collaborative group.

†Missing for 5 patients; 2 in routine group, 3 in collaborative group.

‡Missing for 7 patients; 4 in routine group; 3 in collaborative group.

§Missing for 3 patients; 1 in routine group; 2 in collaborative group.

¶Calculated from patients known not to be on organ donor register.

Table 2.

Characteristics of relative leading on decision/discussion

| All (n=201) | Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to potential donor (%)*: | |||

| Spouse or partner | 97 (49.7) | 46 | 51 |

| Parent(s) | 50 (25.6) | 34 | 16 |

| Child | 26 (13.3) | 9 | 17 |

| Sibling | 18 (9.2) | 7 | 11 |

| Other relative | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 |

| Friend/unrelated | 3 (1.5) | 3 | 0 |

| Sex male or both (parents) present (%)† | 111 (56.6) | 54 | 57 |

| Ethnicity of lead relative (%)‡: | |||

| White | 179 (91.8) | 92 | 87 |

| Asian/Asian British | 7 (3.6) | 3 | 4 |

| Black/Black British | 6 (3.1) | 4 | 2 |

| Chinese/oriental | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 3 |

*Missing for 6 patients: 2 in routine group, 4 in collaborative group.

†Missing for 5 patients: 2 in routine group, 3 in collaborative group.

‡Missing for 6 patients: 2 in routine group, 4 in collaborative group.

Table 3.

Characteristics of requestors

| All (n=201) | Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior doctor at interview (%): | |||

| Trainee | 12 (6.0) | 4 | 8 |

| Consultant | 162 (80.6) | 87 | 75 |

| No doctor | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 |

| Not recorded | 26 (12.9) | 9 | 17 |

| Male senior doctor (%)* | 137 (79.2) | 72 | 65 |

| Male DTC (%)† | 44 (22.0) | 21‡ | 23 |

| Patient’s nurse present at interview (%)§ | 157 (88.2) | 83 | 74 |

DTC=donor transplant coordinator.

*Missing for 1 patient in collaborative group.

†Missing for 1 patient in routine group.

‡ DTC not involved in requesting process in routine group.

§Missing for 23 patients; 8 in routine group, 15 in collaborative group.

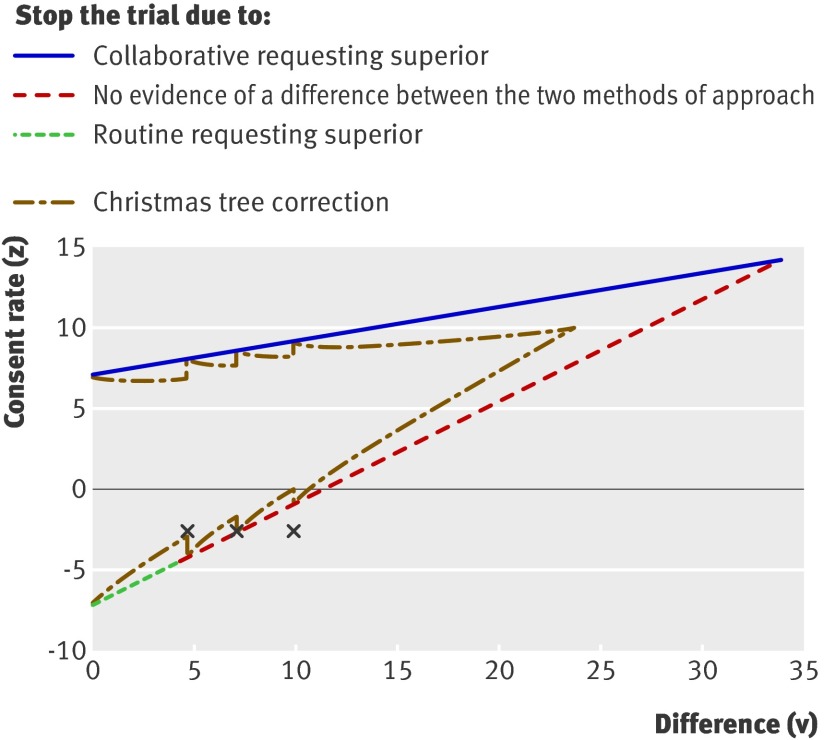

Figure 2 shows the results of the risk adjusted sequential analysis, in which a measure of the adjusted difference in consent rates (Z) is plotted against a statistic summarising the information about this difference (V), which is proportional to the number of relatives. The three points correspond to the planned analyses at 100 and 150 patients, and the final analysis at 201 patients. The point at the first analysis (n=100) was close to the boundary indicating no difference between the groups and formally crossed the boundary on the second inspection (n=150). Trial recruitment continued until agreement to stop the trial had been obtained from both the trial steering committee and the data monitoring and ethics committee. By the time the study closed, 201 relatives had been randomised.

Fig 2 Adjusted difference in consent rates (Z) plotted against statistic summarising information about difference (V), which is proportional to number of sets of relatives. Three crosses correspond to planned analyses at 100 and 150 patients and final analysis at 201 patients. Figure shows routine trial stopping boundaries and boundaries adjusted for discrete monitoring (Christmas tree correction)

Table 4 shows the consent rates for all the sets of relatives by study group assignment (intention to treat). There was no difference in the rates between groups (P=0.53). Of the 201 sets of relatives, the three risk adjustment factors likely to affect consent rates were available for all but six (97%) of the potential organ donors. For these data, the adjusted consent rates were 58% in the collaborative requesting group and 63% in the routine group. The risk adjusted ratio of the odds of consent in the collaborative requesting group relative to the routine group was 0.80 (95% confidence interval 0.43 to 1.53) with a P value of 0.49, adjusted for the interim analysis and over-running. The results of the risk adjustment, given as odds ratios, show that consent was more likely if the patient was white (8.43 for white v non-white, P<0.001), female (0.60 for male v female, P=0.12), and in the 25-34 age group (0.85, 0.29, 1.63, 0.53, and 0.51 for 0-17, 18-24, 25-34, 35-49, 50-59 v ≥60, overall P=0.12).

Table 4.

Consent rates for organ donation

| All (n=201) | Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent to organ donation (%) | 119 (59) | 62 | 57 |

| Any solid organ retrieved (% all patients) | 102 (517) | 57 (56) | 45 (45) |

| Per protocol | 140 | 73 | 67 |

| Consent to organ donation (% per protocol patients) | 89 (64) | 44 (60) | 45 (67) |

| Any solid organ retrieved (% per protocol patients) | 76 (54) | 39 (53) | 37 (55) |

We supplemented the intention to treat analysis with a per protocol analysis. The protocol was followed exactly in only 140 (70%) of the 201 patients. Table 5 lists the specific reasons why the protocol was not followed. The commonest reasons were that the families had already indicated their wishes concerning organ donation before a request was made or that brain stem death tests revealed some evidence of brain stem activity and so organ donation was not appropriate. For the per protocol analysis, the consent rates were 67% (45/67) in the collaborative requesting group and 60% (44/73) in the routine group. The risk adjusted ratio of the odds of consent was 1.47 (0.67 to 3.20, P=0.33), obtained from patients for whom age, sex, and ethnicity were known.

Table 5.

Reasons why allocated requesting did not take place. Figures are numbers (percentages)

| All (n=201) | Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relatives’ decision already known | 12 (6.0) | 9 | 3 |

| Family raised topic of donation | 21 (10.4) | 8 | 13 |

| Patient did not fulfil criteria for brain stem death | 15 (7.5) | 7 | 8 |

| Unexplained violations | 6 (3.0) | 3 | 3 |

| Clinician could not wait for DTC | 3 (1.5) | 3 | 0 |

| DTC could not attend ICU | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 |

| Coroner refused permission for donation | 2 (1.0) | 2 | 0 |

| Patient unsuitable as donor | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 |

DTC=donor transplant coordinator; ICU=intensive care unit.

Table 6 gives the results of the analyses of secondary outcome measures. There was a slightly lower conversion rate (the number of donors from whom solid organs were actually retrieved as a proportion of donors in whom consent for donation had been obtained) in the collaborative requesting group compared with the routine requesting group (79% (45) v 92% (57), P=0.043).

Table 6.

Secondary outcome measures

| Routine request (n=101) | Collaborative request (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Consent to organ donation (primary outcome) (%) | 62 | 57 |

| Organs retrieved (% of consenting) | 57 (92) | 45 (79) |

| Kidney(s) retrieved | 54 | 43 |

| One or both retrieved kidneys transplanted | 51 | 41 |

| Heart retrieved | 11 | 6 |

| Heart transplanted | 10 | 6 |

| Liver retrieved | 51 | 38 |

| Liver transplanted | 45 | 38 |

| Pancreas retrieved | 31 | 19 |

| Pancreas transplanted | 22 | 13 |

| Lung(s) retrieved | 15 | 9 |

| One or both retrieved lung(s) transplanted | 13 | 8 |

| Small bowel transplanted | 0 | 0 |

| Tissue (cornea, etc) retrieved | 32 | 21 |

Discussion

Findings in the context of existing knowledge

We found no evidence for an increase in rates of consent for organ donation from relatives when collaborative requesting was used in place of routine requesting by the patient’s clinician. There was weak evidence that the presence of a donor transplant coordinator at the interview was associated with a reduction in the number of organs retrieved from donors in whom consent for donation was available. The study confirmed previous UK findings that consent was more likely if the patient was white.10

The consent rate for all relatives approached was 59%, almost exactly the figure reported in the large, UK-wide, potential donor audit of at 2754 patients declared dead by brain stem death criteria.1 The percentage of donors with consent for organ donation from whom solid organs were actually obtained was 86% in our study, again close to the 90% reported previously in the UK. Finally, the proportion of white potential organ donors (and families, as in this study the ethnicity of family/friends mirrored the ethnicity of the patient in all cases) at 92% was similar to the 93% found in the audit. We believe our results are therefore generalisable to the whole UK potential donor pool.

Our results are at variance with the results of many observational studies, which report that collaborative requesting increases consent for organ donation.4 There are several possible reasons for this. Collaborative requesting took place in only 73% of assigned cases, but in nearly all of the remaining cases collaborative requesting would have been pointless as the relatives’ views were known or requesting was logistically impossible. Any modest effect of collaborative requesting, however, would have been diluted by these cases in the intention to treat analysis. The slight excess of patients in the routine requesting group whose positive view of organ donation was known might also have diluted a modest benefit from collaborative requesting. It is possible that we did not adopt the optimal procedure for collaborative requesting. A survey undertaken as part of the trial planning process, however, showed that there was no clear single model for collaborative requesting in the UK.5 In the absence of a clear definition for the technique we adopted a pragmatic approach and used whatever collaborative technique the donor transplant coordinators and clinicians agreed on.

The most likely reason for the discrepancy with published case series is simply that collaborative requesting confers little or no advantage in requests for organ donation. Results from non-randomised studies are often not replicated in randomised controlled trials, where the considerable potential for bias is markedly reduced, and this study might be another example. Why the undoubted extra experience of the donor transplant coordinators in interviewing the relatives of potential organ donors conveys no benefit is unclear. Relatives’ decisions might be largely made on the basis of long held beliefs that will not be modified by any requesting technique. A previous observational study suggested this is not the case but it was potentially flawed by selection and recall bias and so might not be reliable.3 The clinician or potential donor’s nurse has usually had prolonged contact with the relatives of potential organ donors, and the incremental benefit of a newly introduced donor transplant coordinators experience might be modest. There is no structured training in making requests for organ donation in the UK, and the additional practical experience of the donor transplant coordinators might require some structure to make it more effective in requests for organ donation.11 Finally, it might be simply that donor transplant coordinators, though experienced in interviewing families in nearly all matters pertaining to organ donation, actually have limited experience in making the initial request.

Irrespective of which arm of the study the relative was randomised to, after an agreement to organ donation the donor transplant coordinator obtained consent for specific organs, as is usual practice in the UK. The lower numbers of all specific solid organs retrieved in the collaborative requesting group, resulting in the lower conversion rate, was therefore unexpected. The data generated by the study did not allow us to determine the reason for the lower conversion rate, which could be related to withdrawal of consent, operational issues with the retrieval teams or local facilities at the donor’s hospital, or late establishment of unsuitability of the donor. Whatever the explanation, the results do have some implication for policy in the UK.

Findings in the context of UK policy and practice

In 2007-8 an additional 10 in-house donor transplant coordinator posts were created with an explicit goal of increasing the consent rate for organ donation.12 The report of the UK Department of Health’s organ donation task force has also recommended the placement of “embedded” coordinators in all hospitals in the UK.13 One of the techniques these embedded donor transplant coordinators use, following practice outside the UK, is promotion of collaborative requesting. In the light of our results it might be more effective to focus on other strategies to increase consent rates, such as the “long contact” technique, where the donor transplant coordinator is involved with the family before an approach is made. There is no better evidence for the efficacy of these techniques, however, than there was for collaborative requesting before this study.

The planning and running of this study was greatly facilitated by the network of donor transplant coordinators in the UK. These coordinators provided the background data from the potential donor audit, delivered the intervention (collaborative requesting), collected the data, and promoted the study. This resource exists in many countries and should be used more fully to study all aspects of organ donation with the same rigour we apply to other procedures and interventions. Anecdotal reports also suggested that the trial itself improved the relationship between intensive care unit staff and donor transplant coordinators.

The ACRE study was based on the assumption that organ donation is of sufficient benefit to organ recipients and to society generally that it is appropriate to test techniques to maximise organ donation consent rates using a study design that required a waiver of consent. This assumption requires wider debate and discussion.

What is already known on this topic

There are several modifiable factors correlated with consent rates for organ donation

Previous research has suggested that “collaborative requesting,” which involves the donor transplant coordinator in the request for organs to a potential donor’s family, increases consent rates for donation

What this study adds

Collaborative requesting can practically be undertaken in only two thirds of requests for organ donation

Collaborative requesting has no effect on the consent rate for organ donation

Trial steering committee

Chris Danbury (chair), ICU consultant; Vicki Barber, trials manager; Dave Collett, statistician; Barry Jenkins, donor family representative; Karen Morgan, donor care and coordination regional manager; Lesley Morgan, trials manager; Ella Poppitt, donor transplant coordinator team leader; Susan Richards, donor transplant coordinator team leader; Duncan Young, ICU consultant, chief Investigator; Sarah Edwards, ACRE trial coordinator; Sandip Patel, ACRE trial coordinator.

Data monitoring and ethics committee

Mark Palazzo, ICU consultant, Susan Todd, statistician; Tom Woodcock, ICU consultant.

Principal investigators and donor transplant coordinators

Rahim Ahmed, Mayday University Hospital; Ryck Albertyn, Worthing Hospital; Ian Andrews, Eastbourne District General Hospital; Karen Austin, Alexandra Hospital, Redditch; Stephen Austin, Mater Infirmorum Hospital, Belfast; Lee Baldwin, Kent and Sussex Hospital, Tunbridge Wells; Andy Ball, Dorset County Hospital, Dorchester; Susan Beards, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester; John Bleasdale, City Hospital, Birmingham; Jonathan Benson, Manchester Royal Infirmary; Keith Bresland, Darlington Memorial Hospital; Bradley Browne, Taunton and Somerset Hospital; Sharon Buchanan, Horton Hospital, Banbury; George Bugelli, Glan Clwyd, Rhyl; Vincent Bulso, Sandwell General Hospital, West Bromwich; Alistair Challiner, Maidstone General Hospital; Kay Chidley, Gloucestershire Royal Hospital, Gloucester; Andy Cohen, Barnet Hospital; Mehrengise Cooper, St. Mary’s Hospital PICU, London; Jason Cupitt, Blackpool Victoria Hospital; Chris Danbury, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading; Steve Dumont, Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport; Michael Ferguson, Leicester Royal Infirmary ICU; James Fraser, Bristol Royal Hospital For Children; Sarah Gillis, Whittington Hospital; Arthur Goldsmith, Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester; Charlie Granger, Royal Lancaster Infirmary; Rob Griffiths, Withybush Hospital, Haverfordwest; Jeremy Groves, Chesterfield and North Derbyshire Royal Hospital; Dave Harling, Rotherham District General; Kay Hawkins, Royal Manchester Childrens’ Hospital; Russell Hedley, Princess Royal University Hospital, Orpington; David Higgins, Southend University Hospital; Jonathan Howes, Yeovil District Hospital; Paul Hughes, Wrexham Maelor Hospital; Julian Hull, Good Hope Hospital, Sutton Coldfield and Solihull Hospital; Tuba Hussain, Peterborough District Hospital; Brian Jenkins, Prince Charles Hospital, Merthyr Tydfil; Chris Kearns, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford NICU; Shond Laha, Chorley and South Ribble Hospital and Royal Preston; Richard Longbottom, Trafford General Hospital, Urmston; Rory Mackenzie, Monklands District General Hospital, Airdrie; Michael Margarson, St Richards Hospital, Chichester; Cathy Maskill, Hillingdon Hospital, Middlesex; Nick Mcneillis, Conquest Hospital; Kevin Morris, Birmingham Children’s Hospital; Alex Manara, Frenchay Hospital, Bristol; Hamid Manji, Milton Keynes General; Chris Newson, Manor Hospital, Walsall; Marlies Ostermann, Guy’s And St. Thomas’ Hospital; Josep Panisello, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford PICU; Tim Peters, West Middlesex University Hospital; Tony Pickworth, Great Western Hospital, Swindon; Jagtar Pooni, New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton; Ian Roberts, George Eliot Hospital, Nuneaton; Peter Royle, University Hospital Of Hartlepool and University Of North Tees; David Simpson, Medway Maritime Hospital, Gillingham; Susan Smith, Cheltenham General Hospital; Clare Stapleton, Wexham Park Hospital; Roger Stedman, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital; Lynn Swanson, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead; Michael Swart, Torbay Hospital, Torquay; Philippa Swayne, Salisbury District Hospital; Angus Vincent, Newcastle General Hospital ICU/PICU; Umeer Waheed, Hammersmith Hospital, London; Martin Walker, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth; Duncan Watson, University Hospital (Walsgrave); Chris Watters, Causeway Hospital, Coleraine; Martin White, Cumberland Infirmary; Dewi Williams, Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary; Peter Wilson, Southampton General Hospital PICU; Paul Woodsford, Royal Glamorgan General Hospital, Pontypridd; Maggie Wright, James Paget Hospital, Gorleston; Duncan Young, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford ICU.

Regional ACRE representatives

Nicki Ashby, Portsmouth; Sarah Beale, South Thames; Gregory Bleakley, Manchester; Sharon Bradshaw, Plymouth; Marian Ryan, Cambridge; Louise Collar, Cardiff; Trish Collins, Portsmouth; Gordon Crowe, Sheffield; Deirdre Cunningham, East Midlands; Eleanor Donaghy, Belfast; Jessica Gregory, South Thames; Sally Holmes, Bristol; Dawn Lee, Manchester; Emma Linnacre, Liverpool; Ella Poppitt, Oxford; Susan Richards, Birmingham; Lynn Robson, Newcastle; Teressa Tymkewycz, North Thames; Deirdre Walsh, Glasgow.

Contributors: Ella Poppitt conceived the study, which was designed by Duncan Young, Dave Collett, Ella Poppitt, and Sarah Edwards. Dave Collett and Claire Hamilton analysed the data. Duncan Young, Dave Collett, Ella Poppitt, and Chris Danbury wrote the manuscript. Duncan Young is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by NHS Blood and Transplant.

The study sponsor (Oxford University) had no role in any aspect of the design or implementation of the study. The funder’s role in study design was limited to the practicalities of setting up the randomisation service and linking the study data with the National Transplant database. The study funder took no part in the interpretation of data, writing the article and the decision to submit it for publication. All the researchers (TSC) had access to the data and approved the final analysis and manuscript.

Competing interests: Dave Collett and Karen Morgan are employed by the study funder, NHS Blood and Transplant. Chris Danbury and Susan Richards serve on the donor advisory group organised by NHS Blood and Transplant.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by Oxford REC A (reference No 06/Q1604/119), with a waiver of the requirement for consent as explained in the text.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3911

References

- 1.Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C, Collett D, Rudge C. Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: audit of intensive care records. BMJ 2006;332:1124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Working Group of the Conference of Medical Royal Colleges and their Faculties in the United Kingdom. The criteria for the diagnosis of brainstem death. J R Coll Phys (Lond) 1995;29:281-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeJong W, Franz HG, Wolfe SM, Nathan H, Payne D, Reitsma W, et al. Requesting organ donation: an interview study of donor and nondonor families. Am J Crit Care 1998;7:13-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpkin AL, Robertson LC, Barber VS, Young JD. Modifiable factors influencing relatives’ decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ 2009;338:b991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Blood and Transplant. Bulletin Spring 2007. 2007. www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/newsroom/bulletin/current_bulletin/acre_research.jsp?null.

- 6.Whitehead J. The design and analysis of sequential clinical trials. 2nd ed. Wiley, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.MPS Research Unit. PEST 4: operating manual. University of Reading, 2000.

- 8.Klieger J, Nelson K, Davis R, Van Buren C, Davis K, Schmitz T, et al. Analysis of factors influencing organ donation consent rates. J Transpl Coord 1994;4:132-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pike RE, Kahn D, Jacobson JE. Demographic factors influencing consent for cadaver organ donation. S Afr Med J 1991;79:264-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy C, Counter C. Potential donor audit. Summary report for the 24 month period 1st April 2007-31st March 2009: UK Blood and Transplant Authority, 2009. www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/statistics/potential_donor_audit/pdf/pda_summary_report_2007-2009.pdf.

- 11.Shafer TJ. Improving relatives’ consent to organ donation. BMJ 2009;338:b701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Blood and Transplant. Annual business plan 2007/08. 2007. www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/downloads/business_plan_200708.pdf.

- 13.Department of Health. Organs for transplants: a report from the Organ Donation Taskforce. 2008. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082122.