Abstract

Summary: Experimental techniques that survey an entire genome demand flexible, highly interactive visualization tools that can display new data alongside foundation datasets, such as reference gene annotations. The Integrated Genome Browser (IGB) aims to meet this need. IGB is an open source, desktop graphical display tool implemented in Java that supports real-time zooming and panning through a genome; layout of genomic features and datasets in moveable, adjustable tiers; incremental or genome-scale data loading from remote web servers or local files; and dynamic manipulation of quantitative data via genome graphs.

Availability: The application and source code are available from http://igb.bioviz.org and http://genoviz.sourceforge.net.

Contact: aloraine@uncc.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Effective use of data from genome-scale assays requires flexible, highly interactive visualization software. To achieve maximum flexibility, genome visualization software should support rapid navigation through multiple zooming scales and across large regions of genomic sequence. Such tools should also enable users to display their data alongside canonical gene annotations, EST alignments and reference datasets harvested from the public domain. Web-based tools, because of their typically tight integration with back-end databases, often make it easy to display one's own data alongside reference datasets, but few match the interactivity and flexibility of desktop software. The Integrated Genome Browser (IGB, pronounced ig-bee) aims to provide the best of both worlds, providing a highly interactive and user-friendly interface, while at the same time offering users the ability to load data from remote databases via web services middleware.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

The IGB is implemented in Java and runs on any computer platform that supports Java version 1.6 or higher.

3 PROGRAM OVERVIEW

The IGB implements a flexible, highly interactive desktop software environment for viewing genome-scale datasets. IGB is the flagship product of the open source Genoviz project, which develops visualization software for bioinformatics and genomics. IGB is based on a library of visualization ‘widgets’ called the Genoviz SDK (Helt et al., 2009). The Genoviz SDK provides a framework for building visualization applications for genomics; it builds on work begun at the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (Helt et al., 1998) and continued at Neomorphic Software and then at Affymetrix when the companies merged (Loraine and Helt, 2002).

Developers at Affymetrix created the first versions of IGB to support visualization of data from the Affymetrix tiling microarray platform. In 2005, the company moved IGB and the Genoviz SDK to a public version control system at Sourceforge.net and released the software under an open source license. Since then, developers have streamlined the user interface and added new features, such as the ability to handle new data sources.

IGB can display data loaded from local files and web servers. IGB loads data from web servers via two protocols: Quickload, an IGB-specific mechanism, and the Distributed Annotation System (DAS), an evolving community standard that supports region-based queries on a genome (Jenkinson et al., 2008). Data providers can also embed links in web pages directing IGB to show a designated region. Examples appear in the web supplement of Cui and Loraine (2006). IGB can load data from multiple sources, allowing users to combine expression, genomic features, methylation, sequence similarity and sequence variation information for a given genome.

The DAS and Quickload mechanisms have complementary strengths. Quickload offers a simple way to load an entire data collection at once, such as the set of curated gene models from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR). Quickload servers are easy to establish, consisting of web accessible or local directories with simple genome descriptor and annotation files. The DAS method works well for data collections that are too large to be viewed productively in their entirety, such as the set of all human ESTs.

Data types IGB can display include gene structure annotations, shown as linked blocks with taller blocks indicating translated regions; genomic alignments of expression array target sequences and probes, shown as linked blocks bearing smaller blocks representing probes; and EST/cDNA genomic alignments, shown as linked spans. IGB displays numerical data associated with base pair positions as highly customizable graphs.

Users can also use IGB to display data saved to local files on their desktop. IGB supports multiple file formats, including BED and PSL formats developed by UCSC Genome Bioinformatics for scored gene models and genomic alignments, respectively, and wig, bar and sgr formats for genome graphs. IGB informatics harmonizes with UCSC tools; users can populate a Quickload server using data from the UCSC Table Browser.

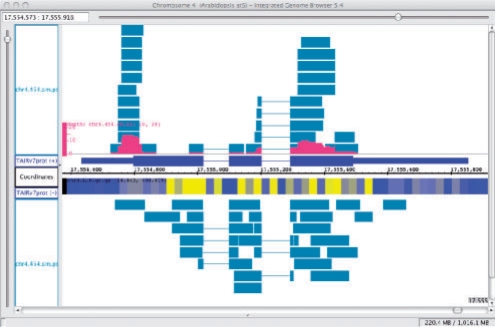

When users load a new dataset or open a file, the new data appear in labeled tracks. Users can click-drag track labels to move tracks to new locations. Right- or control-clicking a track label activates a popup menu with multiple options. One option (Make Annotation Depth Graph) creates a new genome graph summarizing the number of annotations covering each base position, which users can save to a file (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Visualizing ESTs and tiling array data. ESTs (blue) are from a 454 sequencing experiment (Weber et al., 2007). An Annotation Depth Graph (red) summarizes ESTs covering Arabidopsis gene model AT4G37300.1 (dark blue). An expression tiling array genome graph is shown in blue/yellow heatmap style (Yamada et al., 2003). Data are from Arabidopsis seedlings.

IGB supports dynamic zooming and panning through a genome, allowing users to navigate easily through a genome at multiple scales. Zooming focuses on the user's last click, indicated by a vertical stripe in the display. During zooming, the zoom stripe remains stationary as flanking regions expand or contract in an animated fashion as users operate the zoom controls. The zoom stripe provides a base pair pointer in close-up views for inspecting residues at feature boundaries.

The display contains several tabbed control panels and users can move into new windows using the View menu. The Graph Adjuster panel lets the users to fine-tune a graph's appearance and adjust the range of values it displays. It also offers options to add or subtract graphs from each other, providing a first-pass visual assessment of differential expression across sample types.

A literature survey identified 70 articles that used IGB in diverse applications, including transcription factor binding site discovery (Kim et al., 2008; Morohashi and Grotewold, 2009; Zheng et al., 2007), chromatin structure or modification assays (He et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2007; Yagi et al., 2008), statistical methods development (Cui and Loraine, 2009; Xing et al., 2006) and gene expression studies (Lang et al., 2009). Based on users' comments (Gresham et al., 2008) and publications, we conclude that IGB's main appeal is flexibility: it provides a highly interactive environment for viewing large amounts of data and can handle diverse data sources and formats.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We also gratefully acknowledge IGB/Genoviz developers and collaborators past and present, including: Eric Blossom, Steve Chervitz, Ed Erwin, Cyrus Harmon, Ehsan Tabari and David Nix. Adam English created the IGB logo.

Funding: National Science Foundation Arabidopsis 2010 Award 0820371.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Cui X, Loraine A. Computational Systems Bioinformatics Conference. London: Imperial College Press; 2006. Global correlation analysis between redundant probe sets using a large collection of Arabidopsis ATH1 expression profiling data; pp. 223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Loraine AE. Consistency analysis of redundant probe sets on Affymetrix three-prime expression arrays and applications to differential mRNA processing. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham D, et al. Comparing whole genomes using DNA microarrays. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:291–302. doi: 10.1038/nrg2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, et al. Dispersed mutations in histone H3 that affect transcriptional repression and chromatin structure of the CHA1 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1649–1660. doi: 10.1128/EC.00233-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helt GA, et al. BioViews: Java-based tools for genomic data visualization. Genome Res. 1998;8:291–305. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helt GA, et al. Genoviz Software Development Kit: Java toolkit for building genomics visualization applications. >BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:266. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-266. [Epub ahead of print, doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-266] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson AM, et al. Integrating biological data - the Distributed Annotation System. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 8):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S8-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, et al. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang GI, et al. The cost of gene expression underlies a fitness trade-off in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5755–5760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901620106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, et al. A high-resolution atlas of nucleosome occupancy in yeast. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1235–1244. doi: 10.1038/ng2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loraine AE, Helt GA. Visualizing the genome: techniques for presenting human genome data and annotations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Grotewold E. A systems approach reveals regulatory circuitry for Arabidopsis trichome initiation by the GL3 and GL1 selectors. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber AP, et al. Sampling the Arabidopsis transcriptome with massively parallel pyrosequencing. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:32–42. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, et al. Probe selection and expression index computation of Affymetrix Exon Arrays. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, et al. DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions (T-DMRs) in mouse promoter regions demonstrating tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Res. 2008;18:1969–1978. doi: 10.1101/gr.074070.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, et al. Empirical analysis of transcriptional activity in the Arabidopsis genome. Science. 2003;302:842–846. doi: 10.1126/science.1088305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]