Abstract

The widely-disseminated clinical method of motivational interviewing (MI) arose through a convergence of science and practice. Beyond a large base of clinical trials, advances have been made toward “looking under the hood” of MI to understand the underlying mechanisms by which it affects behavior change. Such specification of outcome-relevant aspects of practice is vital to theory development, and can inform both treatment delivery and clinical training. An emergent theory of MI is proposed, emphasizing two specific active components: a relational component focused on empathy and the interpersonal spirit of MI, and a technical component involving the differential evocation and reinforcement of client change talk A resulting causal chain model links therapist training, therapist and client responses during treatment sessions, and post-treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Motivational interviewing, Psychotherapy, Theory, Client-centered, Behavior change, Therapeutic process, Causal chain

Within psychological science much emphasis has been given to what Reichenbach (1938) termed “the context of justification.” Behavioral scientists have prized the process of beginning from a theory, deriving empirical hypotheses, and subjecting these to experimental testing. Good science, Reichenbach maintained, involves a dialogue between this theory-testing process and “the context of discovery” whereby new ideas and theories emerge. Failure to confirm expectations is a particularly fruitful point of meeting between the scientific contexts of justification and discovery. Unexpected findings, if taken seriously, lead one back to the drawing board of discovery to develop a better theory for subsequent testing.

This article reviews three decades of research and development of motivational interviewing (MI). The method and research of MI arose from a series of unexplained outcomes, leading to an emergent theory of the underlying mechanisms of this brief psychotherapy.

The Origins of Motivational Interviewing

Therapist Effects

An unanticipated finding drew attention to the impact of interpersonal processes on behavior change. In preparing for a clinical trial of behavior therapy for problem drinking (Miller, Taylor, & West, 1980), Miller trained nine counselors both in techniques of behavioral self-control training (Miller & Muñoz, 2005) and in the client-centered skill of accurate empathy (Rogers, 1959). After initial certification of the counselors, three supervisors observed them delivering the behavioral intervention with self-referred outpatients and independently rank ordered the extent to which they had manifested empathic understanding while delivering behavior therapy. Therapist empathy during treatment predicted a surprising two-thirds of the variance in client drinking 6 months later (r = .82, p < .0001). Even 12 and 24 months after treatment, counselor empathy continued to account for one-half (r = .71) and one-quarter (r = .51) of the variance in behavioral outcomes, respectively (Miller & Baca, 1983). This effect of therapist style was far larger than differences among the behavioral interventions being compared. Valle (1981) similarly reported that alcoholism counselors’ client-centered interpersonal functioning accounted for a substantial proportion of variance in the relapse rates of randomly assigned clients. Later studies likewise showed large differences in drug use outcomes depending upon the counselor to whom clients had been randomly assigned (Luborsky, McLellan, Woody, O'Brien, & Auerbach, 1985; Luborsky, McLellan, Diguer, Woody & Seligman; 1997; McLellan, Woody, Luborsky, & Goehl, 1988).

A Clinical Style

With these surprising findings, Miller went on sabbatical leave to Bergen, Norway. His original clinical description of motivational interviewing (Miller, 1983) was an unanticipated product of interacting with a group of colleagues there. He had been invited to lecture on behavioral treatment for alcohol problems, and also was asked to meet regularly with a group of young psychologists. This group asked him to demonstrate how he might respond to clients they were treating, and in the role-play process frequently stopped him to ask why he had said what he did, where he was going, and what was guiding his thinking. Thus they caused him to verbalize what had previously been an implicit model guiding his clinical practice, of which he had not been consciously aware, and that differed from the behavior therapies on which he was lecturing.

From notes on this process, Miller wrote down a conceptual model and some clinical guidelines for “motivational interviewing” (MI). It focused on responding differentially to client speech, within a generally empathic person-centered style. Special attention focused on evoking and strengthening the client’s own verbalized motivations for change. Counter-change arguments (“sustain talk,” which was originally subsumed in MI within the concept of “resistance’) represented the other side of the client’s ambivalence, to which the counselor responded empathically, a clear contrast with the confrontational style of addiction counseling at the time (White & Miller, 2007). Pushing or arguing against resistance seemed particularly counterproductive, in that it evoked further defense of the status quo. A guiding principle of MI was to have the client, rather than the counselor, voice the arguments for change.

In describing MI, Miller explored links between this conceptual approach and prior psychological theories. The change-promoting value of hearing oneself argue for change was linked to Festinger’s (1957) formulation of cognitive dissonance, and with Bem’s (1967, 1972) reformulation as self-perception theory. Also relevant was Rogers’ theory of the “necessary and sufficient” interpersonal conditions for fostering change (Rogers, 1959). The supportive atmosphere described by Rogers seemed an ideal, non-threatening context within which to explore clients’ ambivalence and elicit their own reasons for change.

Miller mailed the manuscript to several colleagues, asking for comments. Among them was Ray Hodgson, then editor of the British journal Behavioural Psychotherapy, who persuaded him to publish a reduced version of the conceptual paper (Miller, 1983).

Evaluating the Efficacy of Motivational Interviewing

MI Plus Assessment Feedback: The Drinker’s Check-Up

Returning to New Mexico, Miller continued to develop what had emerged. Analysis of clinical trials pointed to six components that were often present in effective brief interventions (Bien, Miller, & Tonigan, 1993). These were summarized by the mnemonic acronym FRAMES: Feedback, emphasis on personal Responsibility, Advice, a Menu of options, an Empathic counseling style, and support for Self-efficacy. This led to development of a “drinker’s check-up” (DCU) to manifest these components (Miller & Sovereign, 1989). The DCU combined MI with personal feedback of assessment findings in relation to population or clinical norms. The DCU was expected to increase engagement in treatment for alcohol problems, similar to effects previously reported by Chafetz et al. (1962). A randomized trial, however, showed no effect on treatment-seeking relative to a waiting list control (Miller, Sovereign, & Krege, 1988). Instead, the DCU group showed an abrupt decrease in their drinking, a change that was mirrored when the waiting list control group was subsequently given a DCU. This finding was replicated in another randomized trial (Miller, Benefield, & Tonigan, 1993). It appeared that the DCU alone induced significant change in problem drinking. This particular combination of MI with assessment feedback was later termed “motivational enhancement therapy” (MET) and developed into a manual-guided brief treatment (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992).

MI Added to Other Active Treatment

The next three clinical trials evaluated MI as a prelude to treatment. In all three, clients entering substance abuse treatment programs were randomly assigned to receive or not receive a single MI session at the outset of treatment. In all three, clients receiving MI showed double the rate of total abstinence at 3–6 months after inpatient (Brown & Miller, 1993) or outpatient treatment for adults (Bien, Miller, & Boroughs, 1993) or adolescents (Aubrey, 1998), relative to those receiving the same treatment programs without initial MI. MI also significantly increased retention (Aubrey, 1998) and motivation for change as judged by therapists unaware of group assignment (Brown & Miller, 1993).

New Terrain

In 1989 Miller, on sabbatical in Australia, met Stephen Rollnick, who explained that MI was popular in addiction treatment in the United Kingdom, and encouraged Miller to write more about MI. This led to their co-authoring the original MI book (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) elaborating the clinical method (Moyers, 2004). Rollnick proceeded to pioneer new applications of MI in health care (Rollnick, Mason & Butler, 1999; Rollnick, Miller & Butler, 2008).

More than 200 clinical trials of MI have been published, and efficacy reviews and meta-analyses have begun (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Dunn, Deroo, & Rivara, 2001; Erickson, Gerstle, & Feldstein, 2005; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Rubak, Sandbaek, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005) yielding positive trials for an array of target problems including cardiovascular rehabilitation, diabetes management, dietary change, hypertension, illicit drug use, infection risk reduction, management of chronic mental disorders, problem drinking, problem gambling, smoking, and concomitant mental and substance use disorders. Unexpectedly, the specific effect size was larger (Burke et al., 2003) and more enduring (Hettema et al., 2005) when MI was added to another active treatment, a somewhat counterintuitive finding in that one might expect larger effects when the competition is no treatment at all. This suggests a synergistic effect of MI with other treatment methods. Recent volumes have included broader applications of MI in behavior change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) health care (Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008) and psychological services (Arkowitz, Westra, Miller, & Rollnick, 2008).

Multisite Trials

The first multisite trial of MET was Project MATCH, a 9-site psychotherapy trial with 1,726 clients (Project MATCH Research Group, 1993). Outcomes through 3 years of follow-up were similar for a 4-session MET and the two 12-session treatment methods with which it was compared, yielding a cost-effectiveness advantage for MET (Babor & Del Boca, 2003; Holder et al., 2000; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997, 1998a). Similar findings emerged from the 3-site United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial comparing MET with an 8-session family-involved behavior therapy (Copello et al., 2001; UKATT Research Team, 2005a, 2005b).

The Clinical Trials Network of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse has undertaken six multisite trials of MI and MET as compared with treatment-as-usual for drug problems and dependence (Carroll et al., 2002). MI-based interventions have been found to promote sustained reductions in alcohol use (Ball et al., 2007) and increased treatment retention (Carroll et al., 2006). Site-by-treatment interactions also appeared, such that MET exerted a significant beneficial effect at some sites but not others (Ball et al., 2007; Winhusen et al., 2008).

Mixed Findings

Not all trials have been positive. Null findings for MI have been reported, for example, with eating disorders (Treasure et al., 1998), drug abuse and dependence (Miller, Yahne, & Tonigan, 2003; Winhusen et al., 2008), smoking (Baker et al., 2006; Colby et al., 1998), and problem drinking (Kuchipudi, Hobein, Fleckinger, & Iber, 1990). Even within well controlled multisite trials, MI has worked at some sites but not others (Ball et al., 2007; Winhusen et al., 2008). It is apparent that some clinicians are significantly more effective than others in delivering the same MI-based treatment (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998b), and of course even in positive trials a certain proportion of clients do not respond to MI.

The efficacy of MI also can vary across populations. A meta-analysis found that the effect size of MI was doubled when the recipients were predominantly from minority populations, as compared with White non-Hispanic Americans (Hettema, Steele & Miller, 2005). A retrospective analysis of Project MATCH data found that Native Americans responded differentially well to MET, as compared with cognitive-behavioral or 12-step facilitation treatment (Villanueva, Tonigan & Miller, 1007). Similarly, Clinical Trials Network studies found some evidence for differential benefit from MET among pregnant drug users from minority backgrounds (Winhusen et al., 2008).

Such variability in outcomes across and within studies suggests the need to understand when and how a treatment works and the conditions of delivery that may affect its efficacy. Discovering the mediators and moderators of efficacy requires opening the black box of treatment, to examine linkages between processes of delivery and client outcomes, a form of research pioneered by Carl Rogers and his students (Truax & Carkhuff, 1967).

Evaluating Underlying Processes of Motivational Interviewing

An implicit causal chain originally hypothesized for MI was relatively straightforward (Miller, 1983). Behavior change would be promoted by causing clients to verbalize arguments for change (“change talk”; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Conversely, evoking sustain talk would favor behavioral status quo. This is a technical hypothesis regarding the efficacy of MI: that proficient use of the techniques of MI will increase clients’ in-session change talk and decrease sustain talk, which in turn will predict behavior change.

A second factor expected from the outset to be important in MI efficacy was the client-counselor relationship, and more specifically the therapeutic skill of empathic understanding (Gordon, 1970; Rogers, 1959; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Rogers (1959) hypothesized that accurate empathy, congruence, and positive regard are critical therapeutic conditions that create an atmosphere of safety and acceptance in which clients are freed to explore and change. These relational factors were predicted in themselves to promote positive change (Miller, 1983). As described above, studies preceding the introduction of MI supported a specific and strong relationship between therapist empathy and drinking outcomes (Miller et al., 1980; Valle, 1981).

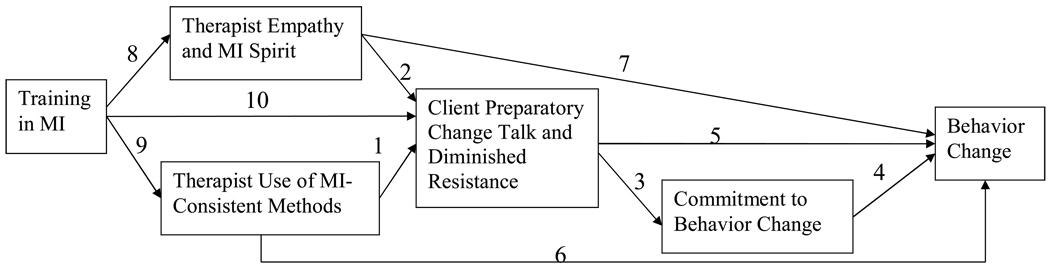

These technical and relational components are not rival or incompatible hypotheses. Psychotherapy research has long postulated a combination of specific (technical) and general or non-specific (relational) factors that influence outcome. Figure 1 illustrates a variety of pathways by which MI may facilitate behavior change. The remainder of this article explores current empirical evidence for the various links in this putative chain.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Relationships Among Process and Outcome Variables in Motivational Interviewing

Measuring MI Processes and Fidelity

Before reviewing MI process research, a brief explanation is in order regarding how therapist fidelity of delivery has been assessed. We know of no reliable and valid way to measure MI fidelity other than through the direct coding of practice samples. Clinicians’ self-reported proficiency in delivering MI has been found to be unrelated to actual practice proficiency ratings by skilled coders (Miller & Mount, 2001; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez & Pirritano, 2004), and it is the latter ratings that predict treatment outcome. Such ratings in turn require the training of coders to a standard of inter-rater reliability, which is itself a challenging process (Miller, Moyers, Arciniega, Ernst & Forcehimes, 2005). The first process rating system for MI – the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code or MISC – was developed by Miller and Mount (2001) and refined in subsequent clinical trials (Miller et al., 2004; Moyers, Martin, Catley, Harris, & Ahluwalia, 2003). The original MISC required three coding passes: one for global skill ratings, one for therapist and client behavior counts, and one for relative talk time. Categories and definitions were refined with experience, eliminating unreliable or redundant codes and sharpening distinctions, to form the current MISC version 2.1 (http://casaa.unm.edu/download/misc.pdf). To reduce time demands, a simplified MI Treatment Integrity (MITI) code was developed focusing only on therapist behavior (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson & Miller, 2005). Subsequently a variety of other MI coding systems have been developed and studied (Madsen & Campbell, 2008). In a review of MI process research, Apodaca and Longabaugh (2009) concluded that MI is reliably differentiated from minimal/placebo control conditions, treatment-as-usual, and other active treatment conditions such as cognitive-behavior therapy, in rates of both MI-consistent and MI-inconsistent therapist responses.

MI Influences Change Talk

For the technical hypothesis to be supported, it is first necessary to show that MI influences the predicted mediator of change (Baron & Kenny, 1986), which in this case is change talk, client utterances that favor the target behavior change. “Resistance” was initially conceptualized as the opposite of change talk, namely speech favoring the status quo (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). In Figure 1, this relationship between MI and client speech is reflected in pathways 1 and 2

In the first study to incorporate process measures of MI, clients receiving the DCU were randomly assigned to one of two styles of personal feedback (Miller et al., 1993). In one style, counselors sought to persuade clients of the need for change, confronting resistance as it arose. In the contrasting MI style, counselors focused on understanding client perspectives through reflective listening and on evoking clients’ own concerns. The same counselors delivered both interventions. Clients in the MI condition voiced about twice as much change talk and half as much resistance. This between-group effect mirrored findings from Patterson and Forgatch (1985), where client resistance increased and decreased in step-function as clinicians shifted within-session between directive and reflective counseling styles. These studies indicate that client change talk and resistance are highly responsive to counselor style.

Further evidence that MI influences client change talk emerged from psycholinguistic analysis of session tapes before versus after clinicians had been trained in MI. Following MI training, counselors’ clients showed significantly higher frequency and strength of change talk, particularly when their MI training had been of the most intensive variety (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Knupsky, & Hochstein, 2004; Miller et al., 2004, Houck & Moyers, 2008). Similar results were obtained following MI training intervention for community mental health workers (Schoener, Madeja, Henderson, Ondersma, & Janisse, 2006).

Moyers and colleagues (Moyers & Martin, 2006; Moyers, Martin, Christopher, Houck, Tonigan, and Amrhein, 2007) provided additional evidence for the link between MI and client change talk. Utilizing a sequential coding system of client and therapist utterances, they analyzed 38 randomly selected MET sessions from Project MATCH. Examining relationships of MI-consistent and MI-inconsistent therapist utterances with client change talk and resistance, they found strong support for the mediational hypothesis. Specifically, MI consistent therapist responses tended to be followed by client change talk, whereas MI-inconsistent utterances were likely to be followed by sustain talk. There also appeared to be a synergy between therapist and client utterances, in that MI elicits change talk which then increases the probability of further MI-consistent therapist responses.

Taken together, these data provide strong support for pathways 1 and 2 in Figure 1. MI-consistent practice does significantly increase client change talk and decrease resistance.

Change Talk Predicts Behavior Change

A second link in the chain is the relationship between client change talk and outcome (paths 3–4 and 5 in Figure 1). The prediction here is that behavior change will be directly related to clients’ change talk during an MI session, and inversely related to sustain talk.

Early support for this linkage came from analysis of DCU session tapes (Miller et al., 1993). The frequency of clients’ in-session resistance strongly predicted their drinking outcomes at 6, 12 and 24 months; the more clients had resisted, the more they drank. No significant relationship was observed, however, between change talk frequency and outcome.

Next, Miller’s team used the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC) to analyze the first 20 minutes of MI session tapes from a clinical trial of MI (Miller et al., 2003). Again, no relationship was found between change talk frequency and behavioral outcome – a problem for the causal chain

Psycholinguist Paul Amrhein, suggested an alternative classification scheme based on his analysis of natural language by which people negotiate change and make commitments (Amrhein, 1992). Using the same clinical trial MI tapes, he differentiated change talk into linguistic subcategories reflecting various components of motivation for change: desire, ability, reasons, need, and commitment. Rather than recording the mere occurrence of these speech acts, he used an established taxonomy to rate the strength of utterances favoring change (drug abstinence) or status quo (continued drug use). His three years of work yielded valuable insights into processes of MI. One of the six linguistic categories directly and robustly predicted behavior change: strength of commitment language. The strength of expressed desire, ability, reasons, and need for change all reliably predicted the strength of commitment, but none of them directly predicted behavior change. In this sense, these seemed to be preparatory steps toward commitment. Furthermore, it was the pattern of commitment strength that predicted outcome: A positive slope of commitment strength across the MI session was associated with abstinence during the subsequent year, with strongest prediction derived from client speech toward the end of the session (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003). Why had we previously failed to detect this effect? In essence, we had been studying the wrong parameter (intercept instead of slope) for the wrong measure (frequency instead of strength) of the wrong variable (change talk instead of commitment) during the wrong part of the session (beginning instead of end).

The prognostic linkage of client commitment language to behavior change was replicated in subsequent research, where the treatment being studied was cognitive-behavior therapy for drug abuse (Aharanovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes & Hasin, 2008). Mean commitment strength predicted drug-free urine samples, and a positive in-session slope of commitment strength predicted treatment retention. Further replication of Amrhein’s findings was provided by Hodgins, Ching and McEwen (2009) with problem gamblers. Commitment language specifically predicted 12-month gambling outcomes, whereas preparatory change talk (desire, ability, reasons and need) did not. These studies offer support for the robustness of commitment as a construct predictive of client outcome, not only in MI but in behavioral treatment more generally.

The practical implication is that MI can elicit clients’ statements of desire, ability, reasons and need for change (paths 1 and 2), with an eye toward evoking increasingly strong commitment to change (path 3). As commitment language emerges, behavior change is more likely to occur (path 4). This converges with cognitive psychology research on the importance of implementation intentions in promoting behavior change (Gollwitzer, 1999; Gollwitzer & Schaal, 1998). A foreshadowing of this pattern had been present in the early description of MI as occurring in two phases (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). In the first phase, the interviewer focuses on eliciting change talk to elicit intrinsic motivation for change. When sufficient motivation appears to be present, the interviewer transitions to a second phase of strengthening commitment to change, focusing on converting motivation into commitment to specific change goals and plans.

Recent research replicates the connection between client change talk and subsequent behavior change. Strang and McCambridge (2004) reported that therapist ratings of clients’ “action-oriented” change talk correlated with post-intervention reductions in cannabis use. Gaume, Gmel and Daeppen (2008) analyzed (with MISC version 2.0) 1055 brief alcohol interventions in a hospital emergency department, and found that client statements of ability (but not commitment) correlated with drinking rates 12 months later. Offering homeless adolescents a 4-session adaptation of MI, Baer, Beadnell, Garrett, Hartzler, Wells, & Peterson (in press) reported that teens’ sustain talk (e.g., “I really love getting high and, besides, I can keep it under control”) predicted substance use at 30- and 90-day follow-up; conversely, verbalizing reasons for change predicted abstinence at follow-up. Moyers et al. (2007) investigated the relationship of client change talk to subsequent alcohol use across all three psychotherapy conditions delivered at the New Mexico site in Project MATCH. In all three therapies, frequency of change talk and sustain talk independently predicted drinking outcomes even after accounting for baseline variance in readiness to change and alcohol use. In this study, change talk and sustain talk did not function as opposite poles of a single dimension, but rather as independent constructs each contributing to drinking outcomes. Summarizing research on substance use disorders alone, Apodaca and Longabaugh (2009) found that client change talk exerted a small to medium effect on behavioral outcome.

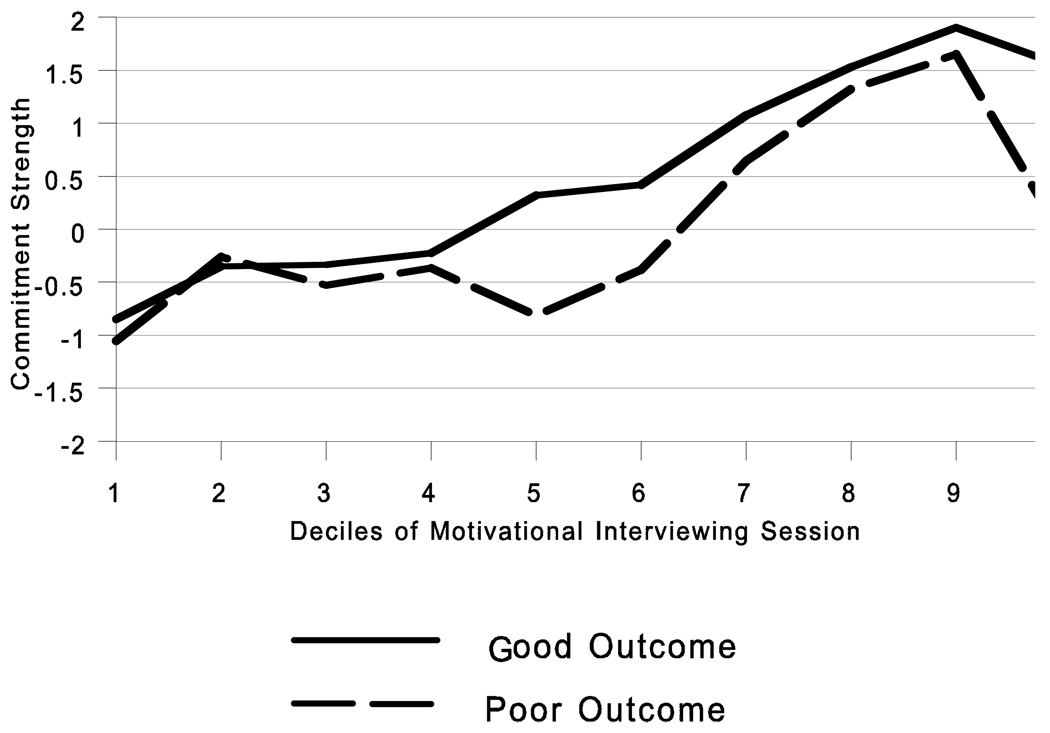

Could psycholinguistic analyses also help us to understand what went wrong when MI does not work? Failure analysis seeks to spin gold from the straw of null results. The data set that yielded Amrhein’s above-described psycholinguistic findings came from a clinical trial that failed to show a main effect of MI when added to drug dependence treatment (Miller et al., 2003). As a first step, Amrhein utilized cluster analysis to differentiate treatment outcomes into four groups. Cluster 1 clients (Changers) entered treatment using illicit drugs on about 80% of days, but maintained high rates of abstinence throughout follow-up. Cluster 2 (Maintainers) showed similarly good outcomes, but had begun treatment abstinent on 80% of days – already well on their way to change. Together these two groups, with pleasing 12-month treatment outcomes, comprised 72% of those in the sample. Cluster 3 (Strugglers; 17% of the sample) started treatment using drugs on 80% of days and averaged about half of their baseline rate during the subsequent year. The fourth group consisted of the 11% whose self-report of abstinence was contradicted by urine drug screens. Amrhein then proceeded to examine what clients in each of these groups had said during their MI session (Amrhein et al., 2003). The language patterns for Changers and Maintainers were quite similar: a steady increase over the course of the session in strength of commitment to drug abstinence. The principal difference was in their starting points. Changers (who had been using on 80% of days) began the session with strong commitment to continued drug use, whereas Maintainers (who had been abstinent on 80% of days) began the session more ambivalent, committing neither to abstinence nor to continued use. Both ended the session expressing strong commitment to abstinence. The combined in-session speech patterns of these two good-outcome groups are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Strength of Client Commitment Language to Drug Use (−) versus Abstinence (+) During a Motivational Interviewing Session: Good versus Poor Treatment Outcomes

In contrast, the speech patterns of the Strugglers looked quite different, and resembled the language pattern of the fourth group who did not honestly report their drug use. Dividing the session into deciles, these groups showed an initial increase in commitment to change that reversed through deciles 3–6. Commitment to abstinence then strengthened dramatically until decile 9, but fell back to zero (ambivalence) at decile 10. The combined in-session speech patterns of these two poor-outcome groups are also shown in Figure 2. The good and poor outcome groups did not differ from each other significantly at baseline on drug use or on measures of pre-treatment motivation for change. Yet the course of their MI sessions, as reflected in commitment language, was quite different, as were their drug use outcomes. What might account for the unusual jagged pattern of the less successful group in Figure 2, with distinct drops in client commitment at deciles 3 and 10?

The single-session MET intervention was manual-guided, with a structured sequence of steps to follow. The session began (deciles 1–2) with open-ended MI, eliciting client change talk. Then the therapist presented personal feedback from the client’s pretreatment assessment (roughly deciles 3–6), after which the therapist returned to MI, (deciles 7–9). Finally, at the end of the session, the therapist developed a change plan with the client and asked for commitment. For the 72% of cases with good outcomes, this sequence flowed relatively smoothly, with steadily increasing strength of commitment to change. For those with poor outcomes, however, it appears that they were not ready, in some sense, to hear their feedback or to agree to a change plan. When the therapist nevertheless pushed ahead with these steps, the client’s commitment level dropped. A skillful MI counselor attends and responds to such in-session fluctuations in change talk and resistance, and would not press ahead with the agenda if the client were not coming along. The structured therapist manual that Miller had authored, however, required the therapist to complete these steps within a single session. The apparent result was that the therapist disregarded client resistance at these points, and lost motivational momentum.

In sum, there is a growing body of research to support paths 3–5, that the natural language utterances of clients do predict behavior change. Further insights are likely to emerge from such research as reliable MI coding systems are refined (Madson & Campbell, 2008).

MI Spirit and Outcome

The relational hypothesis of MI’s efficacy predicts a direct relationship between therapist style and client outcome (path 7 in Figure 1). Rogers (1959) postulated that certain therapeutic conditions in themselves promote positive change. Accurate empathy appears to be a particularly good candidate (Miller et al., 1980; Najavits & Weiss, 1994; Valle, 1981).

Rollnick and Miller (1995) described an underlying spirit of MI as a crucial component of its efficacy. This spirit: (1) is collaborative rather than authoritarian, (2) evokes the client’s own motivation rather than trying to install it, and (3) honors the client’s autonomy. Early evidence for the linkage of MI spirit with change talk and favorable outcome is found in the aforementioned study of Miller et al. (1993). Gaume et al. (2008) also reported a positive correlation between therapist empathy and 12-month drinking outcomes. Furthering this line of inquiry, Moyers, Miller, & Hendrickson (2005) completed process analyses of a clinical trial of MI (Miller et al., 2004). As predicted by the relational hypothesis, clinician interpersonal skills correlated significantly with measures of client involvement. Similarly, two investigations with adult smokers obtained positive correlations among therapist skillfulness, client engagement in treatment (Boardman, Catley, Grobe, Little, Ahluwalia, 2006) and intensity of the therapeutic interaction (Catley, Harris, Mayo, Hall, Okuyemi, Boardman, & Ahluwalia, 2006).

Training in Motivational Interviewing

A final link in the hypothesized chain illustrated in Figure 1 involves MI training. Ideally, training clinicians in MI should change practice behavior and improve their clients’ outcomes. A fully integrated model, not yet demonstrated, would show that training shapes particular clinician responses, which in turn evoke specific in-session client responses that predict client outcomes.

Two early studies found that clinicians reported high satisfaction and significant self-perceived gains in proficiency after an MI workshop (Miller & Mount, 2000; Rubel, Sobell, & Miller, 2000). However, tape-recorded work samples before and after training reflected only modest changes in practice and no difference in clients’ in-session response (e.g., change talk). In short, the workshop convinced clinicians that they had acquired MI skillfulness, but their actual practice did not change enough to make any difference to their clients (Miller & Mount, 2000).

This indicated that trainees need more than a one-time workshop to improve skillfulness in this complex method. Two common learning aids seemed good candidates for improving training: progressive individual feedback on performance, and personal follow-up coaching. The individual and combined impact of these training aids was evaluated in a randomized trial with 140 clinicians (Miller et al., 2004). The design also included a control group given a manual (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and training videotapes (Miller, Rollnick, & Moyers, 1998) for self-directed learning. Relative to pre-training work samples, clinicians in the self-directed learning group showed no improvement of skills in 4 month post-intervention practice samples. Feedback and coaching, both individually and combined, significantly improved clinician MI proficiency beyond the effects of a 2-day training workshop. Improvements were demonstrated in global ratings of MI spirit and empathy (path 8 in Figure 1) as well as in specific technical skills (path 9). One would also hope that when clinicians learn and practice MI, their clients would show increased change talk (path 10). In contrast to the workshop-only study (Miller & Mount, 2001), the clients of participants in this enhanced training did show significant increases in change talk and commitment language, which are in-session proxies of subsequent behavior change (Amrhein et al., 2004; Amrhein et al., 2003). These changes in clinician practice may also exert other effects on client outcomes, through or apart from the mediation of change talk (pathways 6 and 7). A practical challenge in training clinicians in MI, then, is to help them persist in behavior change past an initial workshop exposure that may erroneously convince them that they have already learned the method, a motivational challenge not unlike that of helping clients change lifestyle behaviors.

Discussion

Though originally developed to address substance use disorders (Miller, 1983), MI has now been tested across a wide range of target behavior changes. It has been found to be effective both in reducing maladaptive behaviors (e.g., problem drinking, gambling, HIV risk behaviors) and in promoting adaptive health behavior change (e.g., exercise, diet, medication adherence). The clinical style and apparent mechanisms of change in MI thus seem to be related to generalizable processes of human behavior, and not limited to specific target problems. As discussed above, the effectiveness of MI also appears to be amplified when it is added to other active treatment methods. It therefore shows promise as one clinical tool, to be integrated with other evidence-based methods, for use when client ambivalence and motivation appear to be obstacles to change.

Therapist style and practice can substantially improve or degrade client outcomes. This has been reflected in the variability of outcomes of MI across therapists, sites, and studies. Research on MI sheds light on some of the underlying processes that may be operative well beyond the specific method of MI. Moyers and colleagues (2005, 2006, 2007) have presented data indicating a complex relationship among therapist responses, client speech, and subsequent behavior change. Both the relational (MI spirit) and technical attributes of MI contribute to outcome as mediated by client change talk. Progress has been made toward constructing a causal chain that clarifies how MI affects behavior change. A large efficacy literature shows that MI can directly impact client outcomes (paths 6 and 7 in Figure 1). Linkage has also been established between specific MI practice behavior and client change talk (paths 1 and 2 in Figure 1), a hypothesized mediator of MI’s impact on behavior change. The strength of preparatory change talk predicts subsequent strength of commitment (path 3), both of which have been shown to predict client outcomes (paths 4 and 5). Furthermore, training in MI has been shown to improve clinician performance on MI skills (paths 8 and 9) that are themselves related to client outcome (paths 6 and 7), and to directly increase change talk among clients of trained clinicians (path 10). An independent review of MI process research found that MI implementation is discriminable by MI-consistent therapist behaviors, which in turn predict in-session client responses and post-session treatment outcomes in a manner consistent with the theory of MI stated here (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009, p. 712). An obvious next step is the evaluation of full mediation models integrating the multiple links in this chain (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Longabaugh & Wirtz, 2001).

Even so, causal chain analyses are but a first step in understanding how and why MI effects behavior change. If therapist empathy does enhance client change talk or otherwise improve client outcomes, how does it do so? If the elicitation of client change talk is reliably linked to commitment and behavior change, why is that so? Is it literally the voicing of change talk that causes behavior change? Chanting aloud one hundred times, “I will change, I will change” seems unlikely to make it so. Instead, it is plausible that the processes of MI trigger covert events that are not directly observable, but which result in both increased commitment language and subsequent behavior change. In this case, the observed commitment language is not itself a cause of change, but represents a signal that the covert events are occurring and that change is likely to follow. If that is so, then the verbalization of commitment strength is not a necessary precondition for change. Often, we suspect, the tree falls in the internal forest and no one hears the sound of it.

What might such covert antecedent events be? Some possible descriptors are acceptance, readiness, or decision, with corresponding shifts in perception of self. A reasonable analogy is engagement. When a couple become engaged, they have reached a decision that they are ready (or at least preparing) to make a commitment to each other, which is accompanied by shifts in perception of themselves and their relationship. Engagement is often an emotionally charged, highly significant event, but is not in itself the act of commitment in the presence of witnesses. The public committing act of marriage follows from the private event of engagement. In American culture, at least, engagement does not typically involve binding legal documents. Most often it is a private event, the announcement of which is optional and may be formal or informal. There are some common outward and visible signs of engagement: a ring, statements made to others, focusing of intimacy on the betrothed. Yet none of these is in itself the act of engagement; they are simply reflections of the underlying event. So, too, readiness for change may emerge as a private, discrete shift that opens the door for public commitment.

There remain some interesting wrinkles to be ironed out in the fabric of MI, such as the role of disingenuous change talk. It was not the frequency or absolute level of commitment language (the intercept) that predicted behavior change, so much as a pattern of increasing strength of commitment (positive slope) during a counseling session (Amrhein et al., 2003). Initial commitment level at the beginning of the MI session did not signal behavior change, and clients whose commitment strength did not increase during a session were less likely to be abstaining from drugs at follow-up. It follows that clients who enter a session already professing high commitment may not be the most likely to change. This in turn raises the issue of client honesty. People can offer dishonest change talk, signaling commitments that they have no intention of keeping. Amrhein’s psycholinguistic coding system included attention to nonverbal cues (such as a slight shrug of the shoulders) that when accompanying commitment language signal significantly decreased likelihood of behavioral follow-through. Such subtle cues probably contribute to clinicians’ impressions of client sincerity and motivation, which can in themselves be prognostic of behavior change outcomes (Dunn, Droesch, Johnston & Rivara, 2004) . It is noteworthy that clients who were subsequently dishonest about abstinence showed the same pattern of in-session vacillating commitment as those who reported continued drug use (Amrhein et al., 2003). The pattern of their in-session speech told the truth. Further study of the nature and patterning of client responses, as well as the manner in which intentionality is coded and decoded in everyday conversations (Malle, 2004) may lead to more reliable markers of dissimulation and intentionality toward behavior change.

The relative contributions of the relational and technical components of MI also remain to be clarified. If therapists manifest a high relational level of accurate empathy and MI spirit, how much is efficacy further improved by adding the technical focus on eliciting change talk and commitment language? One randomized clinical trial (Sellman et al., 2001) studied this question with moderately severe problem drinkers, comparing the effects of nondirective counseling, simple feedback, and MET. The MET intervention yielded significantly greater reduction in heavy drinking than did nondirective counseling or a single feedback session, indicating a large effect associated with the technical attributes of MI. Karno & Longabaugh (2005) found an interaction between client anger, reactance and clinician interpersonal style; clients with high levels of anger and reactance did poorly with clinicians who demonstrated behaviors inconsistent with both the spirit and technique of MI. Thus, the answer to the relational versus technical contributions of MI may be a complicated one.

The opposite question – how much does MI spirit add to the technical components – would seem more difficult to evaluate, in part because MI without this underlying spirit is no longer MI. One trial of MI techniques delivered in what appears to be a more authoritarian overall style (Kuchipudi et al., 1990) showed no effect on behavioral outcomes.

It is also likely that other factors will be discovered that play an important role in the processes and outcomes of MI. Clarification of these “active ingredients” could help to focus training on those components that are necessary and/or sufficient for the efficacy of MI, and thereby clarify what aspects can be modified (for example, in cross-cultural adaptations of MI) without compromising its efficacy (Miller, Villanueva, Tonigan, & Cuzmar, 2007; Venner, Feldstein, & Tafoya, 2007).

Summary

After three decades of research, motivational interviewing is a psychotherapeutic method that is evidence-based, relatively brief, specifiable, applicable across a wide variety of problem areas, complementary to other active treatment methods, and learnable by a broad range of helping professionals. A testable theory of its mechanisms of action is emerging, with measurable components that are both relational and technical. This may in turn clarify more general processes that affect outcomes in other psychotherapies (Aharonovich et al., 2008; Moyers et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants K05-AA00133 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, #049533 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and U10-DA01583 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/amp.

Contributor Information

William R. Miller, The University of New Mexico

Gary S. Rose, Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology

References

- Aharaonovich E, Amrhein PC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Hasin DS. Cognition, commitment language, and behavioral change among cocaine-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:557–562. doi: 10.1037/a0012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC. The comprehension of quasi-performance verbs in verbal commitments: New evidence for componential theories of lexical meaning. Journal of Memory and Language. 1992;31:756–784. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne C, Knupsky A, Hochstein D. Strength of client commitment language improves with therapist training in motivational interviewing. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(5):74A. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing in treating psychological problems. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey LL. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 1998. Motivational interviewing with adolescents presenting for outpatient substance abuse treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Del Boca FK, editors. Treatment matching in alcoholism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Beadnell B, Garrett SB, Hartzler B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:570–575. doi: 10.1037/a0013022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ, Taylor RL, Jansons S, Wilhelm K. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1934–1942. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Christoph P, Woody GE, Obert JE, Farentinos C, Carroll KM. Site matters: Multisite randomized trial of motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ. Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review. 1967;74:183–200. doi: 10.1037/h0024835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 6. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Boroughs JM. Motivational interviewing with alcohol outpatients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993;21:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman T, Catley D, Grobe J, Little T, Ahluwalia J. Using motivational interviewing with smokers: Do therapist behaviors relate to engagement and therapeutic alliance? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Miller WR. Impact of motivational interviewing on participation and outcome in residential alcoholism treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel LE, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin DL, Snead N, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Farentinos C, Ball SA, Crits-Cristoph P, Libby B, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin DL, Woody GE. MET meets the real world: Design issues and clinical strategies in the Clinical Trials Network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00255-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catley D, Harris KJ, Mayo MS, Hall S, Okuyemi KS, Boardman T, Ahluwalia J. Adherence to principles of motivational interviewing and client within-session behavior. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;34:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chafetz ME, Blane HT, Abram HS, Golner JH, Hastie EL, Meyers W. Establishing treatment relations with alcoholics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1962;134:395–409. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Weissman K, Spirito A, Woolard RH, Lewander WJ. Brief motivational interviewing in a hospital setting for adolescent smoking: A preliminary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:574–578. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copello A, Godfrey C, Heather N, Hodgson R, Orford J, Raistrick D, et al. United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT): Hypotheses, design and methods. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36:11–21. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Droesch RM, Johnston BD, Rivara FP. Motivational interviewing with injured adolescents in the emergency department: In-session predictors of change. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;32:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health settings: A review. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B. Brief alcohol interventions: Do counselors' and patients' communication characteristics predict change? Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2008;43:62–69. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Simple effects of simple plans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Schaal B. Metacognition in action: The importance of implementation intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:124–136. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T. Parent effectiveness training. New York: Wyden; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, Ching LE, McEwen J. Strength of commitment language in motivational interviewing and gambling outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:122–130. doi: 10.1037/a0013010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Cisler RA, Longabaugh R, Stout RL, Treno AJ, Zweben A. Alcoholism treatment and medical care costs from Project MATCH. Addiction. 2000;95:999–1013. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9579993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Moyers TB. What you do matters: Therapist influence on client behavior during motivational interviewing sessions. Paper presented at the International Addiction Summit; Melbourne, Australia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karno MP, Longabaugh R. An examination of how therapist directiveness interacts with patient anger and reactance to predict alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:825–832. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchipudi V, Hobein K, Fleckinger A, Iber FL. Failure of a 2-hour motivational intervention to alter recurrent drinking behavior in alcoholics with gastrointestinal disease. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51:356–360. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, editors. Project MATCH hypotheses: Results and causal chain analyses. Vol. Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 8. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L, McLellan AT, Diguer L, Woody G, Seligman DA. The psychotherapist matters: Comparison of outcomes across twenty-two therapists and seven patient samples. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1997;4:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L, McLellan AT, Woody GE, O'Brien CP, Auerbach A. Therapist success and its determinants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:602–611. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290084010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle BF. How the mind explains behavior: Folk explanations, meaning, and social interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Woody GE, Luborsky L, Goehl L. Is the counselor an "active ingredient" in substance abuse rehabilitation? An examination of treatment success among four counselors. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1988;176:423–430. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Baca LM. Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy and therapist-directed controlled drinking training for problem drinkers. Behavior Therapy. 1983;14:441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:455–461. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers TB, Arciniega L, Ernst D, Forcehimes A. Training, supervision and quality monitoring of the COMBINE study behavioral interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005 Supplement No. 15:188–195. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Muñoz RF. Controlling your drinking. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S, Moyers TB. Motivational Interviewing (7 videotape series) Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG. The check-up: A model for early intervention in addictive behaviors. In: Løberg T, Miller WR, Nathan PE, Marlatt GA, editors. Addictive behaviors: Prevention and early intervention. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1989. pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG, Krege B. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers: II. The Drinker's Check-up as a preventive intervention. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1988;16:251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Taylor CA, West JC. Focused versus broad spectrum behavior therapy for problem drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:590–601. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.5.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Cuzmar I. Are special treatments needed for special populations? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25(4):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RC. Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Vol. Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 2. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TM. History and happenstance: How motivational interviewing got its start. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2004;18:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T. Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions: Support for a potential causal mechanism. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Catley D, Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS. Assessing the integrity of motivational interventions: Reliability of the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;31:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Tonigan JS, Amrhein PC. Client language as a mediator of motivational interviewing efficacy: Where is the evidence? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(S3):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SML, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Miller W, Hendricksen S. How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. J. Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:590–598. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD. Variations in therapist effectiveness in the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: An empirical review. Addiction. 1994;89:679–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Therapist behavior as a determinant for client noncompliance: A paradox for the behavior modifier. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:846–851. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Project MATCH: Rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:1130–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998a;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Therapist effects in three treatments for alcohol problems. Psychotherapy Research. 1998b;8:455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach H. Experience and prediction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In: Koch S, editor. Psychology: The study of a science. Vol. 3. Formulations of the person and the social contexts. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1959. pp. 184–256. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55:305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EC, Sobell LC, Miller WR. Do continuing education workshops improve participants’ skills? Effects of a motivational interviewing workshop on substance abuse counselors’ skills and knowledge. The Behavior Therapist. 2000;23:73–77. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Schoener EP, Madeja CL, Henderson MJ, Ondersma SJ, Janisse JJ. Effects of motivational interviewing training on mental health therapist behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellman JD, Sullivan PF, Dore GM, Adamson SJ, MacEwan I. A randomized controlled trial of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) for mild to moderate alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:389–396. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J. Can the practitioner correctly predict outcome in motivational interviewing? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(1):83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure JL, Katzman M, Schmidt U, Troop N, Todd G, deSilva P. Engagement and outcome in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: First phase of a sequential design comparing motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;37:405–418. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truax CB, Carkhuff RR. Toward effective counseling and psychotherapy. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- UKATT Research Team. Cost effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: Findings of the randomized UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT) British Medical Journal. 2005a;331:544–548. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UKATT Research Team. Effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: Findings of the randomized UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT) British Medical Journal. 2005b;331:541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle SK. Interpersonal functioning of alcoholism counselors and treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:783–790. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Feldstein SW, Tafoya N. Helping clients feel welcome: Principles of adapting treatment cross culturally. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:11–30. doi: 10.1300/J020v25n04_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Response of Native American clients to three treatment methods for alcohol dependence. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6(2):41–48. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Miller WR. The use of confrontation in addiction treatment: History, science, and time for change. Counselor. 2007;8(4):12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T, Kropp F, Babcock D, Hague D, Erickson SJ, Renz C, Rau L, Lewis D, Leimberger J, Somoza E. Motivational enhancement therapy to improve treatment utilization and outcome in pregnant substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]