Abstract

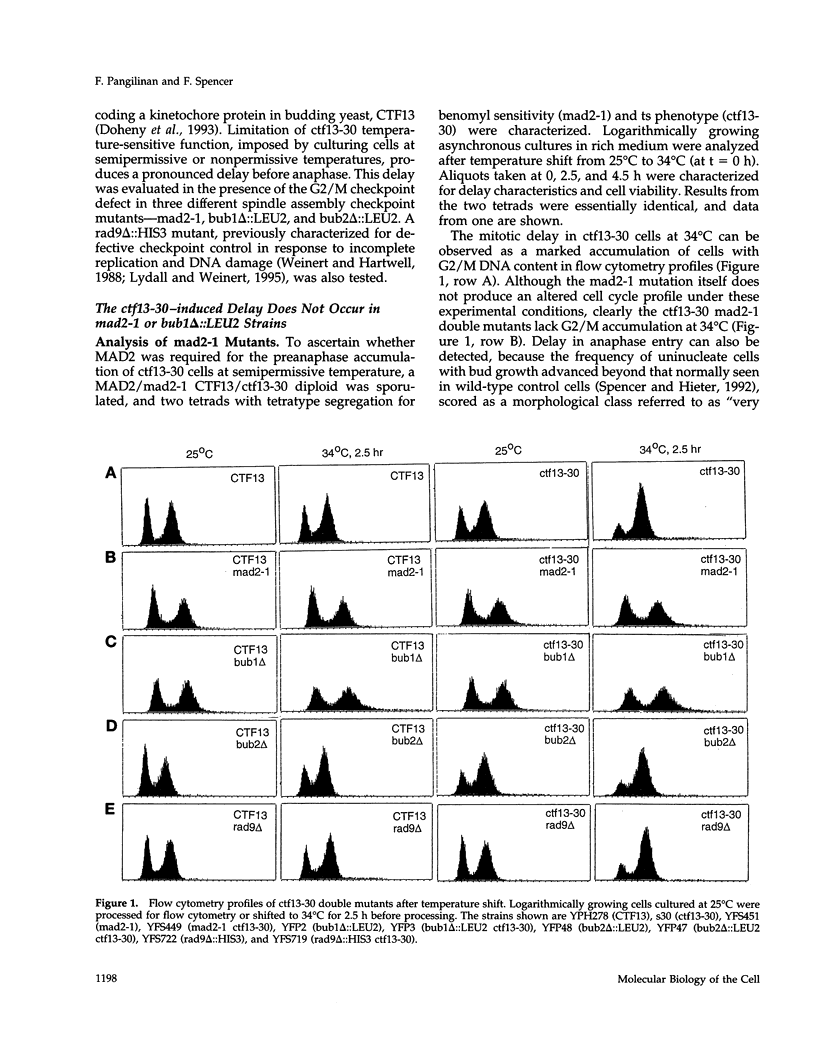

Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells containing one or more abnormal kinetochores delay anaphase entry. The delay can be produced by using centromere DNA mutations present in single-copy or kinetochore protein mutations. This observation is strikingly similar to the preanaphase delay or arrest exhibited in animal cells that experience spontaneous or induced failures in bipolar attachment of one or more chromosomes and may reveal the existence of a conserved surveillance pathway that monitors the state of chromosome attachment to the spindle before anaphase. We find that three genes (MAD2, BUB1, and BUB2) that are required for the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast (defined by antimicrotubule drug-induced arrest or delay) are also required in the establishment and/or maintenance of kinetochore-induced delays. This was tested in strains in which the delays were generated by limited function of a mutant kinetochore protein (ctf13-30) or by the presence of a single-copy centromere DNA mutation (CDEII delta 31). Whereas the MAD2 and BUB1 genes were absolutely required for delay, loss of BUB2 function resulted in a partial delay defect, and we suggest that BUB2 is required for delay maintenance. The inability of mad2-1 and bub1 delta mutants to execute kinetochore-induced delay is correlated with striking increases in chromosome missegregation, indicating that the delay does indeed have a role in chromosome transmission fidelity. Our results also indicated that the yeast RAD9 gene, necessary for DNA damage-induced arrest, had no role in the kinetochore-induced delays. We conclude that abnormal kinetochore structures induce preanaphase delay by activating the same functions that have defined the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast.

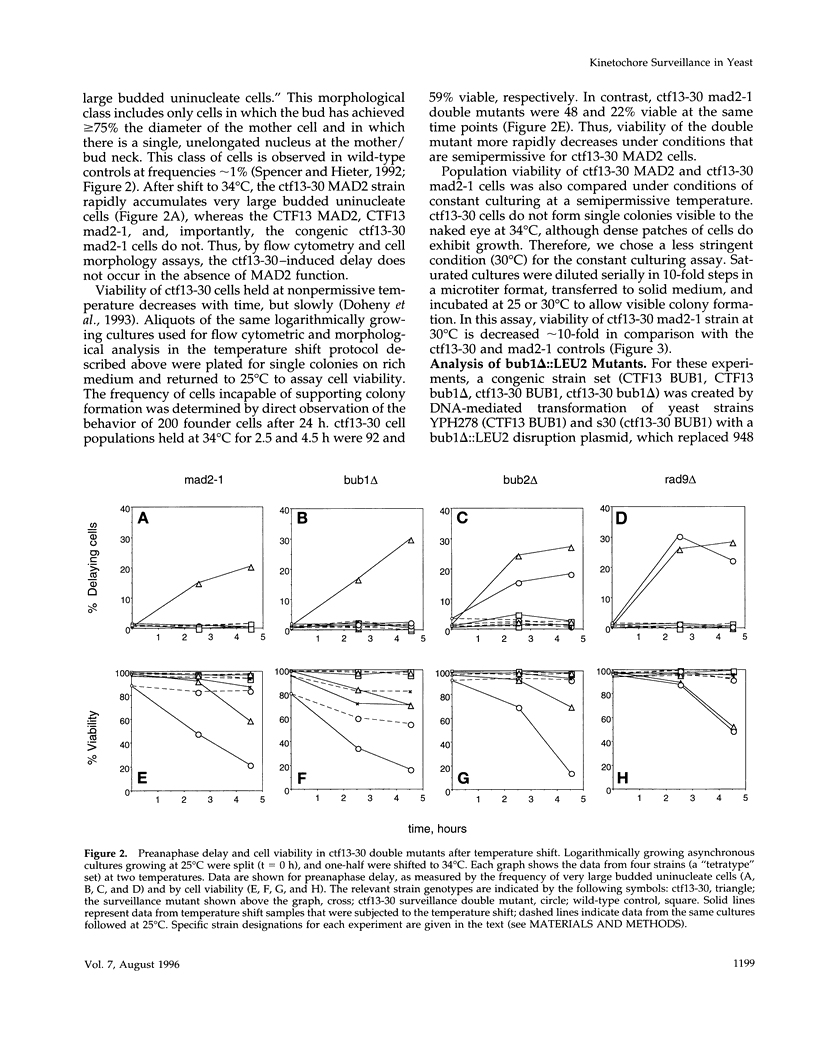

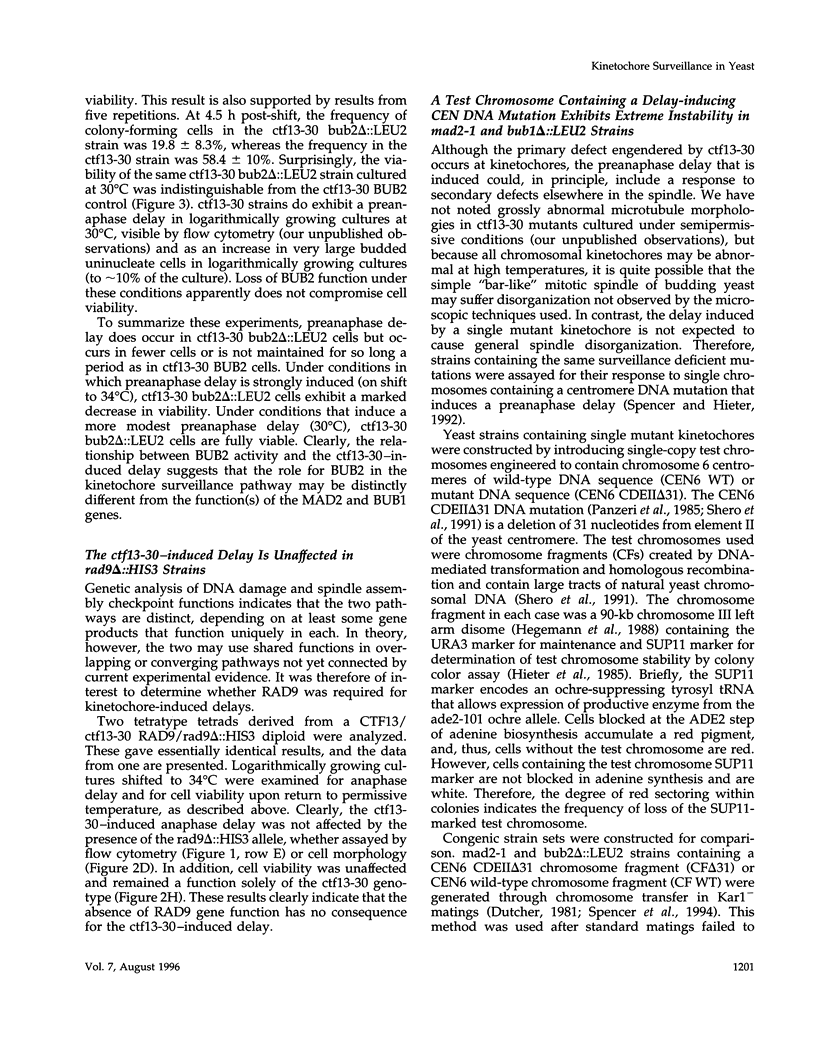

Full text

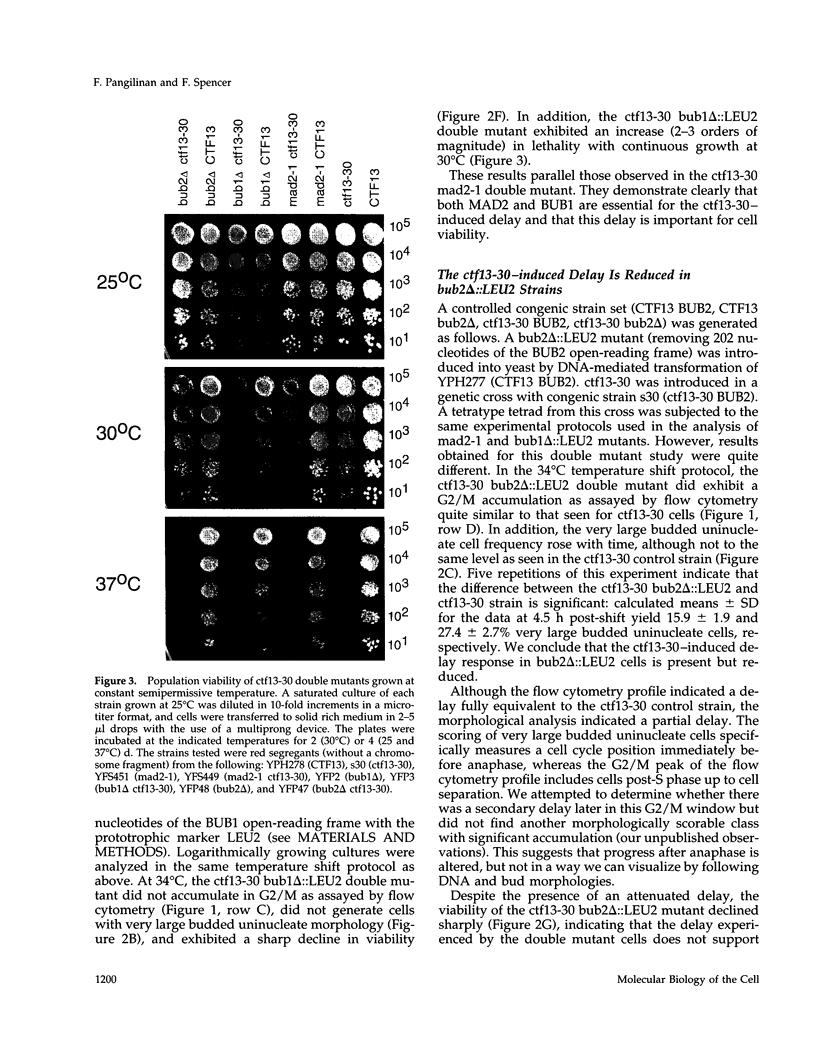

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bernat R. L., Borisy G. G., Rothfield N. F., Earnshaw W. C. Injection of anticentromere antibodies in interphase disrupts events required for chromosome movement at mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1990 Oct;111(4):1519–1533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S. T. Motor neurons and neurofilaments in sickness and in health. Cell. 1993 Apr 9;73(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90151-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. S., Gorbsky G. J. Microinjection of mitotic cells with the 3F3/2 anti-phosphoepitope antibody delays the onset of anaphase. J Cell Biol. 1995 Jun;129(5):1195–1204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. M., Hoekstra M. F. The cellular responses to DNA damage. Trends Cell Biol. 1995 Jan;5(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T. R., Dunphy W. G. Cdc2 regulatory factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;6(6):877–882. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher S. K. Internuclear transfer of genetic information in kar1-1/KAR1 heterokaryons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1981 Mar;1(3):245–253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C., Marks J., Reymond A., Simanis V. The S. pombe cdc16 gene is required both for maintenance of p34cdc2 kinase activity and regulation of septum formation: a link between mitosis and cytokinesis? EMBO J. 1993 Jul;12(7):2697–2704. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh P. Y., Kilmartin J. V. NDC10: a gene involved in chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1993 May;121(3):503–512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick K. G., Murray A. W. Mad1p, a phosphoprotein component of the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995 Nov;131(3):709–720. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Weinert T. A. Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989 Nov 3;246(4930):629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegemann J. H., Fleig U. N. The centromere of budding yeast. Bioessays. 1993 Jul;15(7):451–460. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegemann J. H., Shero J. H., Cottarel G., Philippsen P., Hieter P. Mutational analysis of centromere DNA from chromosome VI of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Jun;8(6):2523–2535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.6.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieter P., Mann C., Snyder M., Davis R. W. Mitotic stability of yeast chromosomes: a colony color assay that measures nondisjunction and chromosome loss. Cell. 1985 Feb;40(2):381–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt M. A., He L., Loo K. K., Saunders W. S. Two Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinesin-related gene products required for mitotic spindle assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992 Jul;118(1):109–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt M. A., Totis L., Roberts B. T. S. cerevisiae genes required for cell cycle arrest in response to loss of microtubule function. Cell. 1991 Aug 9;66(3):507–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker T. C., Thomas J. H., Botstein D. Diverse effects of beta-tubulin mutations on microtubule formation and function. J Cell Biol. 1988 Jun;106(6):1997–2010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugerat Y., Spencer F., Zenvirth D., Simchen G. A versatile method for efficient YAC transfer between any two strains. Genomics. 1994 Jul 1;22(1):108–117. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter K. J., Eipel H. E. Flow cytometric determinations of cellular substances in algae, bacteria, moulds and yeasts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1978;44(3-4):269–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00394305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. S., Prakash L. Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae selectable markers in pUC18 polylinkers. Yeast. 1990 Sep-Oct;6(5):363–366. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Murray A. W. Feedback control of mitosis in budding yeast. Cell. 1991 Aug 9;66(3):519–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Nicklas R. B. Mitotic forces control a cell-cycle checkpoint. Nature. 1995 Feb 16;373(6515):630–632. doi: 10.1038/373630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall D., Weinert T. Yeast checkpoint genes in DNA damage processing: implications for repair and arrest. Science. 1995 Dec 1;270(5241):1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J. R. Structural and mechanical control of mitotic progression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:613–619. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. W., Kirschner M. W. Dominoes and clocks: the union of two views of the cell cycle. Science. 1989 Nov 3;246(4930):614–621. doi: 10.1126/science.2683077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas R. B. Chromosome micromanipulation. II. Induced reorientation and the experimental control of segregation in meiosis. Chromosoma. 1967;21(1):17–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00330545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas R. B., Ward S. C., Gorbsky G. J. Kinetochore chemistry is sensitive to tension and may link mitotic forces to a cell cycle checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 1995 Aug;130(4):929–939. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature. 1990 Apr 5;344(6266):503–508. doi: 10.1038/344503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeri L., Landonio L., Stotz A., Philippsen P. Role of conserved sequence elements in yeast centromere DNA. EMBO J. 1985 Jul;4(7):1867–1874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C. L., Schultz A., Cole R., Sluder G. Anaphase onset in vertebrate somatic cells is controlled by a checkpoint that monitors sister kinetochore attachment to the spindle. J Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;127(5):1301–1310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B. T., Farr K. A., Hoyt M. A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae checkpoint gene BUB1 encodes a novel protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;14(12):8282–8291. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof D. M., Meluh P. B., Rose M. D. Kinesin-related proteins required for assembly of the mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 1992 Jul;118(1):95–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof D. M., Meluh P. B., Rose M. D. Multiple kinesin-related proteins in yeast mitosis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:693–703. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz P. J., Solomon F., Botstein D. Isolation and characterization of conditional-lethal mutations in the TUB1 alpha-tubulin gene of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988 Nov;120(3):681–695. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shero J. H., Koval M., Spencer F., Palmer R. E., Hieter P., Koshland D. Analysis of chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:749–773. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94057-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989 May;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly C., Balczon R., Brinkley B. R., Schatten G. Microinjected centromere [corrected] kinetochore antibodies interfere with chromosome movement in meiotic and mitotic mouse oocytes. J Cell Biol. 1990 Oct;111(4):1491–1504. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer F., Gerring S. L., Connelly C., Hieter P. Mitotic chromosome transmission fidelity mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1990 Feb;124(2):237–249. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer F., Hugerat Y., Simchen G., Hurko O., Connelly C., Hieter P. Yeast kar1 mutants provide an effective method for YAC transfer to new hosts. Genomics. 1994 Jul 1;22(1):118–126. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunnikov A. V., Kingsbury J., Koshland D. CEP3 encodes a centromere protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1995 Mar;128(5):749–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkiel J., Cooke C. A., Saitoh H., Bernat R. L., Earnshaw W. C. CENP-C is required for maintaining proper kinetochore size and for a timely transition to anaphase. J Cell Biol. 1994 May;125(3):531–545. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Burke D. J. Checkpoint genes required to delay cell division in response to nocodazole respond to impaired kinetochore function in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995 Dec;15(12):6838–6844. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. A., Hartwell L. H. Cell cycle arrest of cdc mutants and specificity of the RAD9 checkpoint. Genetics. 1993 May;134(1):63–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. A., Hartwell L. H. The RAD9 gene controls the cell cycle response to DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1988 Jul 15;241(4863):317–322. doi: 10.1126/science.3291120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E., Winey M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle pole body duplication gene MPS1 is part of a mitotic checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 1996 Jan;132(1-2):111–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells W. A., Murray A. W. Aberrantly segregating centromeres activate the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1996 Apr;133(1):75–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirkle R. E. Ultraviolet-microbeam irradiation of newt-cell cytoplasm: spindle destruction, false anaphase, and delay of true anaphase. Radiat Res. 1970 Mar;41(3):516–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]