Abstract

Entrenched poor health and health inequity are important public health problems. Conventionally, solutions to such problems originate from the health care sector, a conception reinforced by the dominant biomedical imagination of health. By contrast, attention to the social determinants of health has recently been given new force in the fight against health inequity. The health care sector is a vital determinant of health in itself and a key resource in improving health in an equitable manner. Actors in the health care sector must recognize and reverse the sector's propensity to generate health inequity. The sector must also strengthen its role in working with other sectors of government to act collectively on the deep-rooted causes of poor and inequitable health.

The production of better population health outcomes is usually equated with improvements in health care. But this is a somewhat crude equation. All too often, health care sectors, firmly rooted in medicine, do not demonstrate active engagement with the wide determinants of patients' health; do not ensure, through a nuanced understanding of social determinants, that care services are made available and accessible to all social groups equitably; and have not been as proactive as one might expect, given the evidence on social determinants of health, in engaging and working with other government sectors (as a kind of steward in support of those sectors' own activities) to ensure that all government entities appreciate their potential to affect health and health equity.

This situation must change. As a first step toward change, some questions need to be answered. How are we as a global community performing with respect to health and health equity, both within countries and between them? What are key obstacles to improving integrated action by health care sectors on the social determinants of health? And what might a reoriented health care sector—one that takes health equity as a central goal and, in so doing, engages with the entire range of social determinants of health—look like? We first offer some definitions of key terms to clarify our discussion.

We follow the lead of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) in viewing social determinants as the social, political, economic, and cultural conditions in which people live and work and the structural drivers of these conditions. We define the health care sector as the sector typically responsible for hospital- and community-based health services, public health surveillance, health promotion and workforce planning, standard setting, and regulation of public and private health care services.

We use the term stewardship to describe the various roles that can be taken by actors in the health care sector in collaboration with their counterparts in other government sectors. We selected this term deliberately to recognize and minimize the risk of health imperialism (the domination of the health care sector over agendas shared with other sectors). Stewardship implies the general duty of care for a population's health borne by government as a whole; it involves a nuanced balance of leadership and facilitation in the relationship between the health care sector and other government sectors, ranging from education through infrastructure and urban planning to trade. We define inequity as unjust and avoidable inequalities.

THE EVIDENCE IS IN

The past 200 years have seen a doubling of the human life span.1 Although enormous advances in biomedical interventions and health technologies have been made during that time, major inequities in health persist. There are grotesque inequities in health between rich and poor countries,2–5 and the gap is increasing. In low- and middle-income countries, health care provision has been adversely affected by waves of structural adjustment (promoted by international finance institutions since the 1980s to impose fiscal austerity on poor and heavily indebted countries). Such structural adjustment programs, in many cases, have resulted in weakened state-funded health care systems, weakening in turn the capacity of health care systems to implement primary health care and respond to health crises such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic in a comprehensive way.6

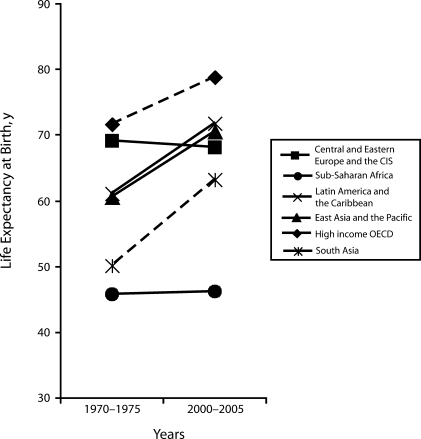

And there are striking—and in some cases increasing—health inequities within countries at all levels of economic wealth.7–13 These health inequities are evident for most common diseases, including infectious diseases, cardiovascular disease, and many cancers, as well as psychosocial problems and injuries. In some places, life expectancies are actually beginning to fall in the face of chronic disease epidemics and exacerbated socioeconomic inequalities (Figure 1).14

FIGURE 1.

Life expectancy at birth, by world region, 1970–1975 and 2000–2005.

Note. CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Data were derived from the Human Development Report 2006.85

Within countries, such health inequities are not found only between the worst off and the rest of society. Rather, most countries exhibit a gradient in health in which each step lower in the social hierarchy is associated with worse health outcomes.5 Health inequity, as a manifestation of structural social, economic, and political inequalities—themselves strongly associated with societal tension, violence, and conflict—represents a potentially urgent problem with respect to human, national, and global security.15 The implication is that health inequity is a problem affecting everyone in society, one that requires a whole-of-government response.

There is now a considerable body of evidence pointing to the vital importance of social and economic factors at a collective, societal level in directly determining population health and health equity. Many of the social and economic advances of the past were made without any explicit attention to improving health but, in many cases, resulted in improvements in health nonetheless. A conclusion to draw from such outcomes is that although major social, economic, and political processes and policies may not be intended to affect health or health equity (for better or worse), in all likelihood they will. Historical case studies16 and contemporary analyses of political systems17,18 indicate that governments are most successful in promoting health when they invest in social protection and create health-promoting environments.

Evidence also indicates that life expectancy has been linked more to improved living conditions than to improved health care services.16,19,20 Equally, the capacity of the health care sector to improve population health and health equity is strongly influenced by other sectors.21,22

Yet, despite this evidence, countries' investments in and through the health care sector are overwhelmingly confined to the provision of curative health services, especially hospital services, rather than being channeled to prevention and health promotion. Moreover, when health promotion is incorporated at all, it is generally aimed at changing the behavior of individuals rather than creating wider physical, social, and economic environments supportive of healthy behavior.23,24 In any case, an investment emphasis on new medical interventions tends to increase health inequities because interventions reach more advantaged groups before, if ever, trickling down.25 Simply continuing to chase new biomedical and technical interventions will clearly not be enough.

In addition, although it is widely recognized that access to health care is a crucial social determinant of health, an inverse care law26 operates whereby those with the worst health status receive less health care, and this pattern is evident both within countries (poor and excluded groups are in poorer health than are their richer counterparts but are less able to access or benefit from care) and between them (poor countries have the highest burdens of disease but the lowest levels of financial, technical, and institutional resources to address them).

In low- and middle-income countries in particular, socioeconomic inequalities translate into huge inequities in health care use.27 As a simple example, approximately 150 million residents of countries with limited public sector health care have suffered financial catastrophe—a large proportion of them pushed further down or backward into poverty as a result of paying for their health care—owing to the introduction over recent decades of much wider application of user fees and the increasingly large role of private health care providers.28

A BIOMEDICAL IMAGINATION OF HEALTH AND CARE

The health care sector is clearly dominated by a biomedical imagination. In the sections to follow, we discuss the implications of this situation in terms of the bias toward individualism that drives the choice of care and prevention strategies and tends to result in health care being viewed as a commodity that can be readily privatized. In such a worldview, curative medicine is privileged over strategies that emphasize disease prevention and health promotion. Health care sectors need to focus much more on understanding the dynamics of health in populations and the ways in which the factors that promote population health differ from those that affect individuals.

Biomedicine and Individualism

The health care models favored by most advanced industrial countries and health care sectoral development in many poorer countries under current aid and trade arrangements reflect the influence of a long-standing Western biomedical and individualistic concept of health. Biomedical individualism is discernible at the heart of much health policy in rich and poor countries alike (with some notable exceptions).29

Lukes'30 analysis of power in public policy suggests that powerful actors (e.g., medical personnel) are able to shape understanding and perceptions so that only policies and interpretations that fit with the dominant discourse are considered. The persistence and extent of medical dominance have been noted consistently since the rise of modern medicine, most famously by Virchow in the 19th century and more recently by Doyal31 and Navarro and Shi32 in relation to advanced economies, and by Sanders and Richard33 in relation to low- and middle-income countries.

The dominance of a medical imagination in health care over the long term can be seen in the context of wider social and class relations in which medical conservatism reflects wider forces of social and political conservatism and resistance to heterodox knowledge.34 But the biomedical model also fits neatly with the dominant contemporary political discourse of market individualism, with its culture of opportunity over entitlement and its disavowal of the distributive role of the state.35,36 It is not surprising, under these international conditions, that health care sectors promote the provision of clinical care and focus on exhorting individuals to change their behavior at the expense of a focus on features of the environmental, political, or economic systems that produce ill health and inequity.37–39 Downstream responses to health problems appear seductively easy and attract more short-term political support than responses that focus upstream on structural causes of ill health.40

Growing Privatization

Commodification of social resources under the dominance of the market has resulted in a large and growing private health care sector—dramatically so in low-income countries—that profits from the growth and expansion of clinical care and pharmaceutical treatments. In this environment, health budgets are devoted overwhelmingly to hospitals, medical and pharmaceutical services, and biomedical research, and budget incentives encourage patient throughput rather than health outcomes.

Although medical education and research are overwhelmingly clinical in focus, it is important to note that the medical imagination and the biomedical model of health care cannot be portrayed as simply a matter of one influential class group subordinating the views of the mass majority. The medical imagination is supported by a strong public demand for curative services. That demand is, itself, fueled by a popular imagination of medicine as the key to quick physical fixes and ever-extending longevity.41 The preference in media reportage for cures for cancer and other diseases contributes to the tenacity of this popular imagination while the greater population health effects of more fundamental but less dramatic public health and social policy reforms go unheralded.42

Bias Toward Curative Medicine

The compact of medical, political, commercial, and popular dedication to curative medicine is reflected in health care spending trends in the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 2006, the vast majority of these countries spent between 8% and 10.5% of their gross domestic product on health care (excluding the United States, which spent 15.3% of its gross domestic product on health care). Thirty years ago, the same OECD countries were spending between 5% and 7%.43 The extent of these spending increases and the often relatively small health gains spread unevenly across groups (witness, for instance, the extremely poor health status of Aboriginal people in Canada and Australia)44—compounded by the recognition of escalating health care costs to come with the growing burden of chronic disease in poor countries—raise the question of the sustainability of the biomedical model.

Leaving aside the fact that health care sectors as currently constituted appear to exacerbate health inequities, the logic of increasing longevity, increasingly prevalent chronic conditions, and increasingly sophisticated (and expensive) pharmaceutical and medical products and interventions points to the possibility of health care systemic overload and bankruptcy. Such considerations may make more urgent the argument in favor of balancing the medical imagination with a sociological one, recognizing the limits to medicine, and contributing to a political climate in which medical and pharmaceutical spending are reset in a more rational proportion to investment in action on social determinants of health.

Understanding Population Health Dynamics

Changing the medical imagination requires a grasp of the way that risk factors work in populations and the potential for action on social determinants to improve population-scale health. Rose45 eloquently established that the determinants of individual health are not the same as those of population health. The crucial message—if we are to challenge and change the medical mind-set, whether by force of the moral imperative of health equity or the pragmatic imperative of fiscal sustainability—is that treating high-risk individuals or those already suffering from disease does not have much impact on population health, whereas changing a risk factor across an entire population by only a small amount has a substantial impact (e.g., a small reduction in the mean body mass index [BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared] of a population will make very little difference to any one individual but will be significant in terms of the population's chronic disease burden).

This simple observation, bolstered by the arguments in favor of equitable distribution of care through a health care sector attending to social determinants as much as individual outcomes, makes reorientation of the health care sector a powerful common agenda for supporters of social justice and economic efficiency. Rose's insistence on a population view also reminds us that if we concentrate solely on shifting the mean, this averaging may mask growing health inequities, especially given that those nearer the top of the gradient are best placed to benefit from health promotion measures.46

A REORIENTED HEALTH CARE SECTOR

Earlier we asked what a health care sector reoriented toward action on the social determinants of health, with health equity as a central goal, would look like. The box on the next page summarizes the characteristics of such a reorganized health care sector, and a number of these characteristics are discussed in the sections to follow.

Characteristics of a Health Equity–Oriented Health Care Sector

Leadership: Improving the equity performance of the health care system

Focus on comprehensive primary health care

Decision making processes that involve local communities

Universally accessible care that is publicly funded, preferably through general taxation; good-quality health services free at point of use

Planning, including allocation of resources, based on the needs of populations within a social determinants of health framework

Policy statements and strategies that are explicit about closing the health equity gap and the need for action on the social determinants of health to achieve this goal in all programs, including those that are disease focused

Evidence that the health care system has a systematic approach to increasing its spending on community-based services until a significant proportion of funding is devoted to community-based care and that it has reformed its financing system so that it rewards keeping people healthy through preventive action rather than throughput of clinical cases

Stewardship: Working with other sectors to improve health and health equity

Presence of health sector advocacy program with other sectors regarding the need for action on the social determinants of health and the importance of intersectoral action

Development of expertise to establish a health equity surveillance system and to conduct cross-government health equity impact assessments on a regular basis along with private-sector activities

Reform of medical and health professional education so that the importance of social determinants is reinforced in theory teaching, clinical training, understanding of population health perspectives, and skill development for interprofessional collaboration

Training and education of professionals (including urban and transport planners, teachers, and architects) on the importance of social determinants of health

Specified, funded program of research on the impact of social determinants of health and evaluation interventions designed to address them, with a significant proportion of health research funding devoted to studies on social determinants

It is notable that action on social determinants of health implies both the leadership of the health care sector in influencing a wide range of social and economic policy fields—from education through town planning to trade and industry—and a stewardship function in supporting the health-influencing policy and practice development of other sectors. This nuanced combination of leadership and stewardship resides at the heart of our conception of the role of the health care sector in a world interested in equitable health and effective action that will lead to equity.

Universal Health Care

Universal health care entitles everyone to the same range of (quality) health services irrespective of income, social status, or residency. Almost all OECD countries have adopted, in one form or another, the principle of universal provision of health care.47 The uneven incidence of health care needs across a population and the potentially catastrophic costs of unsubsidized care—and the equally appalling consequences of being unable to access care—combine to make a forceful argument in favor of maximizing the pooled risk of individual citizens. This implies ensuring that health care is freely available to all at point of use and is paid for through national contributions (with cross subsidies for poorer groups) collected from citizens via direct taxation or insurance.

Almost all universal health care systems in OECD countries were built, over long periods, from selective coverage systems (e.g., for specific cadres of workers) and from indigenous risk-pooling mechanisms.48 It can be argued that low-income countries in particular are hardly likely to be able to scale up from extremely low levels of health care spending per capita to levels that approach OECD countries' spending.49 However, evidence from some countries—such as Thailand, Costa Rica, Brazil, Venezuela, and Ghana—suggests that significant expansion toward universal provision, whether of insurance policy coverage or coverage of specific health care services, is feasible.

Public-Sector Leadership

There is evidence that public spending on health can have positive effects on both health-adjusted life expectancy50 and health equity.51 Given the degree to which heavily privatized systems rely on clinical throughput to maximize shareholder profits, the establishment (or reestablishment) of strong public health care sectors based on the principles of equitable, universal coverage will require considerable political and sectoral leadership.

The link between mixed private and public funding of health services and rapid cost escalation is well-established. The private medical sectors in low- and middle-income countries are even more strongly oriented toward a richer clientele than government health services, reinforcing the need, from a health equity viewpoint, for a revitalized public sector.52 Strengthening the public health care sector in low- and middle-income countries requires addressing the root causes of the weaknesses of these systems, including limited taxation capacity and limited ability on the part of the government to translate spending into delivery (including tackling the “brain drain”53,54), and ameliorating the effects on health systems of global economic and political power differences.25

Available, Accessible, and Acceptable Care

Commitment to the principle of a universalist health care sector is commendable but somewhat pointless if people cannot obtain and use health care services. More acute in poor countries but characteristic of inequities in access to, use of, and benefit from health care services across all countries, issues associated with gender and ethnicity, geographical residency and cultural norms, and income significantly condition the availability, accessibility, and acceptability of health care. Barriers to care not associated with the health care sector include cultural factors (such as limited decision-making power and access to resources among women), distance, lack of transport, inability to take time off work, and limited education. Within health care sectors, access is limited by gender insensitivity, fragmentation of services, inadequate service quality (including lack of availability of medication, equipment, and personnel), and inappropriate hours of operation.

Health care–related costs, both direct and indirect, are among the most significant barriers to access, most acutely affecting the poorest sectors of society.55 If primary health care is not accessible, people may delay seeking help, rely on last-minute emergency care, and lose the benefits of continuity of care.56 A responsive health care sector must recognize and address each of the factors just described.

Comprehensive Primary Health Care

Countries with strong primary care infrastructures have been shown to have lower costs and to perform better in the health care arena.57,58 Primary care has been found to be more effective than specialty care in preventing illness and death, and it is associated with more equitable distributions of health.56 At the same time, effective links with tertiary care services are needed (e.g., obstetric emergency care to reduce maternal mortality). The case for a comprehensive system is strong and has been made since the World Health Organization (WHO)59 established its key strategies: community participation, multidisciplinary teams, appropriate technology, grounding in a social understanding of health, focus on disease prevention and health promotion, and cross-sector action.

Most significantly, comprehensive primary health care would include district-based programs that involve all relevant sectors, as well as community members, and that take action to promote health. These initiatives would emphasize citizen participation and social empowerment,60,61 which, in combination with information about the power of social determinants to improve health, would create a popular constituency for health care system changes. Reawakening powerful health care sector commitments from the WHO's Health for All strategy, many countries now view comprehensive primary health care as a way of “improving the quality, equity, efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness of their health systems.”62

Focus on Prevention and Health Promotion

There is growing international evidence1,63 of better population health outcomes and cost reductions in instances in which economic incentives are created for community-based preventive health care provision rather than individual curative care provision; in particular, these include initiatives such as capitation and salaries rather than fee for service. In rich countries, the population health improvements gained from individual curative health care are questionable, especially when judged alongside the potential of an approach focusing on the social determinants of health. This fact is likely to be a powerful incentive for governments to find effective means of promoting population health equitably.

In the case of poorer countries, approaches that do not rely on costly medical care and expensive technology will be attractive and will create a strong incentive for taking an approach focusing on social determinants of health. In these countries, investments in social determinants such as living conditions can provide substantial health gains, and health and health equity gains will be even larger if these interventions are designed to reach poorer groups.64

With the backing of strong bureaucratic and political leadership, health care personnel might be better supported in looking beyond the delivery of clinical services and asking “What happens to the people we serve when they go home? Do their homes, workplaces, leisure activities, communities, and wider environments support recovery and ongoing good health?” In so doing, health care personnel will be better able to find ways to reduce demand for care services by focusing on prevention and health promotion. As an example, in one study malnourished children in Jamaica were followed up after their discharge from the hospital, and these home follow-up visits focused on illness prevention and health promotion (e.g., helping parents find jobs and shelter and develop income-generation skills).65 Such initiatives will require a radical change in the way most health care is funded so that strong incentives are provided for taking action to prevent disease and promote health.

Appropriately Skilled Workforce

Just as public education about the role of social determinants may help shift the way people demand health care services, medical and professional education among health workers will be needed to strengthen their knowledge of and confidence in social determinants, population health approaches, and approaches to achieving health equity so that they will be able to lead the reorientation we envisage. Health sector workforces around the world have been trained in systems that emphasize clinical treatment with a strong disease focus. Although some initiatives that integrate social science understanding into training are in place, these initiatives remain marginal and are often accorded only lip service.66

All graduating health care professionals need to understand that improving a population's health requires strategies and skills different from, and additional to, those currently required for clinical work. A central element in training curricula targeted toward health professionals should be how to work with counterparts from other sectors. Equally, health sector actors could contribute to cross-sectoral action by providing health-focused support of training in other sectors such as urban and transport planning and architecture. The current political, media, and popular concern in high-income (and, increasingly, middle-income) countries about overweight and obesity is likely an effective means through which to promote such cross-sectoral health action by demonstrating the compelling evidence for the effects of urban design (e.g., encouraging car use rather than walking).

Adequate Information Systems

Ignorance is the enemy of effective action. A simple lack of knowledge of aspects of health care delivery and health inequity makes action to improve conditions extremely difficult politically and practically. Health equity–focused surveillance can ensure that good data are available on population health status and a range of social determinants, as well as ensuring that these data are stratified according to social group. For some countries, this requires strengthening of the most basic information systems, including comprehensive birth and death registration.47 Health care sectors can and should act as central clearinghouses that bring surveillance data together in one place and ensure they are widely accessible so that other sectors are aware of the health and health equity effects their actions produce.

Related to this general surveillance function, health sector actors can promote other sectors' use of health equity impact assessment tools to help decision makers systematically and prospectively assess the probable effects of policies, programs, projects, or proposals on health equity in a given population. Such assessments, which should occur as a matter of course, will require investment in training, tools, and resources.67,68

Research-Supported Interventions

According to the CSDH, the People's Health Movement,69,70 and the Global Forum for Health Research,71 funding for intervention research on social determinants of health is negligible relative to funding for biomedical science research. The health care sector should advocate for investment in a program of research that will produce evidence on the social determinants of health and health equity, including the effectiveness of health equity interventions. In countries with established health and medical research funding bodies, this would entail a dedicated budget and a review process in which there is an appreciation of the need for research designs suitable for studying complex social interventions. Strengthening research on the social determinants of health also requires WHO and the various global health initiatives to fund research programs on social determinants of health and health equity in low- and middle-income countries.

LEADERSHIP

Strong global, national, and local leadership will be required to bring about the health sector reorientation we are calling for. The momentum to bring about this leadership commitment would be greatly enhanced by a concerted push from civil society.

Global Leadership

The reorientation of health care systems that we envisage will require strong technical support from WHO. The fact that WHO established the CSDH is positive; implementing the commission's recommendations is the next crucial step. To provide the technical support necessary, WHO needs to strengthen its institutional capacity globally, regionally, and within countries to advise on and provide useful implementation tools relating to the social determinants of health. The Priority Public Health Conditions Knowledge Network, created to support the CSDH, has already initiated institutional strengthening processes. It is vital that this work continues.

Ideally, WHO would have a program of work relating to each of the points in the box on page 1970. Some of its existing initiatives, most noticeably the Healthy Cities program,72 have shown considerable promise as vehicles for stronger action on social determinants of health. These existing initiatives need more investment, including a well-funded research and evaluation program and capacity development program.

National Leadership

We recognize that change of the type we describe here will not be for the fainthearted. Strength, determination, and time will be required for the health care sector to take the lead and become responsive to social determinants and health equity and to be in a position to lead others in effective action. Most governments are characterized by vertical siloed organizations that frequently are in fierce competition for attention and resources. At the same time, these governments often struggle to protect the sustainability of their health care systems.

We recognize that the changes we envisage in the health care sector are unlikely to come about unless action on health equity and social determinants of health becomes a whole-of-government enterprise. The CSDH suggested the establishment of health equity targets as a measure of societies' success and the development of a cross-government body focused on health equity and led directly by the head of government.

The existence of such targets and such a body require empowered health sector leadership, but they also offer a route to greater health sector empowerment. Instead of being lone cabinet voices, ministers of health would be seen as central to the achievement of a healthy and successful society and would be in a position to support other ministers. For example, they could provide advice to the ministers of education (on early childhood development), planning (on how new urban developments are likely to affect health equity), infrastructure (on the fundamental contributions of water, sanitation, and housing to good health), and agriculture (on ensuring nutritious food supplies). Their position would also be stronger if they were able to draw on strong departmental health equity surveillance, working health equity impact assessments, and passionate, vocal, and visible civil society partners.

Stewardship

Health care sectors also need to lead by taking a stewardship role in supporting a cross-government approach that focuses on the social determinants of health and acting as catalysts to involve people and institutions across society. The Health in All Policies programs of the European Union73 and South Australia74,75 encourage cross-sectoral approaches based on social determinants of health and demonstrate the role that health ministries can play in introducing whole-of-government approaches to health equity.

In most countries, building an approach focused on the social determinants of health will not mean starting completely afresh but rather building on existing programs of work. Many countries have implemented healthy cities or other cross-sectoral programs relating to issues such as injury prevention, food and healthy weight, violence, and drug use. The final report of the CSDH47 contains many examples of cross-sector health initiatives, including those concerning housing, urban development, education, and trade policy. In other work, the CSDH examined ways of increasing the effectiveness of cross-sector efforts in relation to health equity.76

Other positive—if still limited—examples are comprehensive community-based health services that ground their interventions in an understanding of how everyday life affects their users' health. Illustrations are Canada's Centres de Sante et de Services Sociaux,77 community health centers in Australia78 and the United States,79 women's health centers,80 and small community health programs in poor countries, as well as the support provided by WHO to its member states to strengthen such services.81,82 All of these examples, which operate on the principles WHO established for primary health care in 1978,83 offer practical models of how health care services can incorporate a perspective on social determinants. Yet, despite the promise they show, they remain marginal and receive relatively very little research attention. Increased investment is needed to ensure that these programs are strengthened in every way possible.

Local Leadership

If health equity is to become a central concern of governments and health care sector actors, it must become a concern of the people. There must be popular demand for fairer health from the very people who suffer the injustice of inequitable health. And if governments and health care sectors are to recognize and act on their collective responsibility in health—to shift investments and actions from cure to prevention, from treating the consequences of poor health outcomes to strengthening cross-sectoral activities focusing on the determinants of people's everyday health—there needs to be strong popular demand.

The CSDH recognized from its beginning that change will require a social movement. Thus, it developed a civil society stream of work that was intended to strengthen the existing civil society focus on social determinants.84 Health care sectors need to use the power and passion of civil society to mobilize popular support for a reorientation toward a social determinants approach and a focus on health equity. These efforts will require health sector personnel to be creative and skilled in working constructively with civil society actors in a way that respects their contribution and does not merely pay lip service to it.

CONCLUSIONS

The 21st century is posing complex problems: continuing, persistent inequity; a changing climate with dire predicted consequences for human health; an epidemic of chronic disease grafted on an existing overload of infectious diseases; and increasing rates of mental illness and violence. There is a demand for new solutions, and the CSDH's final report47 sets out a clear, evidence-informed agenda for change. Central to this change is a dynamic health care sector that can lead by example, produce data and evidence on health equity and social determinants, and truly live up to its promise of promoting the health and well-being of all.

Acknowledgments

F. E. Baum was supported by an Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship. We are grateful for research assistance from Rama Ramanathan in preparing the final version of the article for publication.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed.

References

- 1.Williams J. 50 Facts That Should Change the World. Cambridge, England: Icon Books; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofrichter R, ed Health and Social Justice: A Reader on Politics, Ideology and Inequity in the Distribution of Disease. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crombie IK, Irvine L, Elliot L, Wallace H. Closing the Health Inequalities Gap: An International Perspective. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenbach JP. Health inequalities: Europe in profile. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/socio_economics/documents/ev_060302_rd06_en.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Marmot M. Health in an unequal world. Lancet 2006;368:2081–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders DM, Todd C, Chopra M. Confronting Africa's health crisis: more of the same will not be enough. BMJ 2005;331:755–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw M, Dorling D, Gordon D, Smith GD. Putting time, person and place together: the temporal, social and spatial accumulation of health inequality. Crit Public Health 2001;11:289–304 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1138–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser K, Shkolnikov V, Leon DA. World mortality 1950–2000: divergence replaces convergence from the late 1980s. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:202–209 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorling D, Shaw M, Smith GD. Global inequality of life expectancy due to AIDS. BMJ 2006;332:662–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980–2000. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:969–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leinsalu M, Vagero D, Kunst AE. Estonia 1989–2000: enormous increase in mortality differences by education. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1081–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackenbach JP, Bos V, Andersen O, et al. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in six Western European countries. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:830–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy M, Bobak M, Nicholson A, Rose R, Marmot M. The widening gap in mortality by educational level in the Russian Federation, 1980–2001. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1293–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart F, ed Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group Violence in Multiethnic Societies. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szreter S. The importance of social intervention in Britain's mortality decline c.1850–1914: a re-interpretation of the role of public health. Soc Hist Med 1988;1:1–37 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navarro V, Muntaner C, Borrell C, et al. Politics and health outcomes. Lancet 2006;368:1033–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coburn D. Health and health care: a political economy perspective. In: Raphael D, Bryant T, Rioux M, eds Staying Alive: Critical Perspectives on Health, Illness and Health Care Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, Inc; 2006:59–84 [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeown T. The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage or Nemesis? London: Nuffield Provincial Hospital Trust; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szreter S, Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:650–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Towards High-Performing Health Systems. Paris, France: Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Levelling Up (Part 2): A Discussion Paper on European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health. Liverpool, England: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Policy Research on Social Determinants, University of Liverpool; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baum F. The New Public Health. 3rd ed.Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raphael D. Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, Inc; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silve AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet 2000;356:1093–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;1:405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houweling TAJ, Ronsmans C, Campbell OMR, Kunst AE. Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: an international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:745–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:972–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tesh S. Hidden Arguments: Political Ideology Prevention Disease Policy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukes S. Power: A Radical View. London, England: Macmillan; 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyal L. The Political Economy of Health. London, England: Pluto Press; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro V, Shi L. The political context of social inequalities and health. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders D, Richard C. The Struggle for Health: Medicine and the Politics of Underdevelopment. London, England: Macmillan; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foucault M. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. New York: Pantheon; 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beresford Q. Governments, Markets and Globalisation: Australian Public Policy in Context. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global Health Watch 2: An Alternative Health Report. London, England: Zed Books; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Illich I. Medical nemesis. Lancet 1974;303:918–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarro V. Political power, the state, and their implications in medicine. Rev Radic Polit Econ 1977;9:61–80 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox RC. The medicalization and demedicalization of American society. In: Knowles JH, ed Doing Better and Feeling Worse: Health in the United States New York, NY: WW Norton; 1977:9–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ 2003;326:1419–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Illich I. Death undefeated. BMJ 1995;311:1652–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferriman A. BMJ readers choose the “sanitary revolution” as greatest medical advance since 1840. BMJ 2007;334:11117235067 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD health data 2008: statistics and indicators for 30 countries. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/health/healthdata. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 44.Stephens C, Porter J, Nettleton C, Willis R. Disappearing, displaced, and undervalued: a call to action for Indigenous health world wide. Lancet 2006;367:2019–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baum F. Cracking the nut of health equity: top down and bottom up pressure for action on the social determinants of health. Promot Educ 2007;14:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available at: http://whqlibdocwho.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Lister J. Health Policy Reform: Driving the Wrong Way? Enfield, England: Middlesex University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ensor T. Transition to Universal Coverage in Developing Countries: An Overview. York, England: International Programme, Centre for Health Economics, University of York; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mackintosh M, Koivusalo M. The Commercialisation of Health Care: Global and Local Dynamics and Policy Responses. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Houweling TAJ, Kunst AE, Looman CWN, Mackenbach JP. Determinants of under-5 mortality among the poor and the rich: a cross-national analysis of 43 developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1257–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans RG. Economic myths and political realities: the inequality agenda and the sustainability of Medicare. Available at: http://www.chspr.ubc.ca/files/publications/2007/chspr07-13W.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 53.Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet 2004;364:1984–1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1810–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Coalition on Health Care Health insurance costs. Available at: http://www.nchc.org/facts/cost.shtml. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 56.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization The world health report 2008: primary health care now more than ever. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/08_overview_en.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 58.Starfield B, Shi L. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Health Policy 2002;60:201–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Health Organization Declaration of Alma-Ata. Available at: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 60.Kahssay HM, Oakley P. Community Involvement in Health Development: A Review of the Concept and Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vega-Romero R, Torres-Tovar M. The Role of Civil Society in Building an Equitable Health System. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasgow NJ, Sibthorpe B, Gear A. Primary health care position statement: a scoping of the evidence. Available at: http://www.agpn.com.au/site/content.cfm?page_id=6910¤t_category_code=104&leca=16. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 63.Health Systems Knowledge Network. Final Report of the Health Systems Knowledge Network of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gakidou E, Oza S, Fuertes CV. Improving child survival through environmental and nutritional interventions: the importance of targeting interventions toward the poor. JAMA 2007;298:1876–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott-McDonald K. Elements of quality in home visiting programmes: three Jamaican models. In: Young ME, ed From Early Child Development to Human Development: Investing in Our Children's Future Washington, DC: World Bank; 2002:233–253 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benbassat J, Baumal R, Borkan JM, Ber R. Overcoming barriers to teaching the behavioral and social sciences to medical students. Acad Med 2003;78:372–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris E. NSW Health HIA Capacity Building Program: Mid-term Review. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, University of New South Wales; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wismar M, Blau J, Ernst K, Figueras J. The Effectiveness of Health Impact Assessment: Scope and Limitations of Supporting Decision-Making in Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders D, Labonte R, Baum F, Chopra M. Making research matter: a civil society perspective on health research. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:757–763 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCoy D, Sanders D, Baum F, Narayan T, Legge D. Pushing the international health research agenda towards equity and effectiveness. Lancet 2004;364:1630–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matlin SA. The millennium development goals: substance and spirit. In: Matlin S, ed Global Forum Update on Research for Health 2005—Health Research to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals London, England: Pro-Brook Publishing; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Healthy cities and urban governance. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/healthy-cities. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 73.Ståhl T, Wismar M, Ollila E, Lahtinen E, Leppo K, eds Health in All Policies: Prospects and Potentials. Helsinki, Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kickbusch I. Health in all policies: setting the scene. Public Health Bull S Aust 2008;5:3–5 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sherbon T. The impact of chronic disease and the role of population health. Public Health Bull S Aust 2008;5:17–18 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Improving Health Equity Through Intersectoral Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and Public Health Agency of Canada; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levine D. The reform of health and social services in Quebec. Healthcare Papers 2007;8(extra issue):46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baum F, Fry D, Lennie I, eds Community Health: Policy and Practice in Australia. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Pluto Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lefkowitz B. Community Health Centers: A Movement and the People Who Made It Happen. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broom DH. Damned If We Do: Contradictions in Women's Health Care. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Comprehensive Community- and Home-Based Health Care Model. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pan American Health Organization Renewing primary health care in the Americas. Available at: http://www.paho.org/English/AD/THS/primaryHealthCare.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2009

- 83.Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Final Report of the Civil Society Work Stream of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Human Development Report 2006. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2006 [Google Scholar]