Abstract

Objectives. We investigated the possible relationship between being shot in an assault and possession of a gun at the time.

Methods. We enrolled 677 case participants that had been shot in an assault and 684 population-based control participants within Philadelphia, PA, from 2003 to 2006. We adjusted odds ratios for confounding variables.

Results. After adjustment, individuals in possession of a gun were 4.46 (P < .05) times more likely to be shot in an assault than those not in possession. Among gun assaults where the victim had at least some chance to resist, this adjusted odds ratio increased to 5.45 (P < .05).

Conclusions. On average, guns did not protect those who possessed them from being shot in an assault. Although successful defensive gun uses occur each year, the probability of success may be low for civilian gun users in urban areas. Such users should reconsider their possession of guns or, at least, understand that regular possession necessitates careful safety countermeasures.

Among a long list of issues facing the American public, guns are third only to gay marriage and abortion in terms of people who report that they are “not willing to listen to the other side.” In concert with this cultural rift, scholarly discussion over guns has been similarly contentious.1 Although scholars and the public agree that the roughly 100 000 shootings each year in the United States are a clear threat to health, uncertainty remains as to whether civilians armed with guns are, on average, protecting or endangering themselves from such shootings.2–4

Several case–control studies have explored the relationship between homicide and having a gun in the home,5,6 purchasing a gun,7,8 or owning a gun.9 These prior studies were not designed to determine the risk or protection that possession of a gun might create for an individual at the time of a shooting and have only considered fatal outcomes. This led a recent National Research Council committee to conclude that, although the observed associations in these case–control studies may be of interest, they do little to reveal the impact of guns on homicide or the utility of guns for self-defense.3,10

However, the recent National Research Council committee also concluded that additional individual-level studies of the association between gun ownership and violence were the most important priority for the future.3 With this in mind, we conducted a population-based case–control study in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to investigate the relationship between being injured with a gun in an assault and an individual's possession of a gun at the time. We included both fatal and nonfatal outcomes and accounted for a variety of individual and situational confounders also measured at the time of assault.

METHODS

We applied a case–control study design to determine the association between being injured with a gun in an assault and an individual's possession of a gun at the time. To determine this in the most generalizable way, we chose our target population to be residents of Philadelphia prompting the use of population-based control participants. We considered trial, cohort, and matched cohort designs but for various reasons (ethical considerations, prohibitively long implementation time, limited generalizability, and so on.) these were not pursued.

We assumed that the resident population of Philadelphia risked being shot in an assault at any location and at any time of day or night. This is an acceptable assumption because guns are mobile, potentially concealable items and the bullets they fire can pass through obstacles and travel long distances.11–14 Any member of the general population has the potential to be exposed to guns and the bullets they discharge regardless of where they are or what they are doing. As such, we reasonably chose not to exclude participants as immune from hypothetically becoming cases because they were, for instance, asleep at home during the night or at work in an office building during the day. Instead we measured and controlled for time-based situational characteristics that might have changed, but did not eliminate, the possibility of being shot in an assault.

Participant Identification and Matching

Gunshot assault cases caused by powder charge firearms were identified as they occurred, from October 15, 2003, to April 16, 2006. The final 6 months of this period were limited to only fatal cases. We excluded self-inflicted, unintentional, and police-related shootings (an officer shooting someone or being shot), and gun injuries of undetermined intent. We excluded individuals younger than 21 years because it was not legal for them to possess a firearm in Philadelphia and, as such, the relationship we sought to investigate was functionally different enough to prompt separate study of this age group. We excluded individuals who were not residents of Philadelphia as they were outside our target population and individuals not described as Black or White as they were involved in a very small percentage of shootings (< 2%). Even after these exclusions, the study only needed a subset of the remaining shootings to test its hypotheses. A random number was thus assigned to these remaining shootings, as they presented, to enroll a representative one third of them.

Data coordinators at the Philadelphia Police Department identified and enrolled new shooting case participants as they occurred by reviewing an electronic incident tracking system and interviewing police officers, detectives, and medical examiners. Basic data for eligible case participants were wirelessly sent to the University of Pennsylvania where study leaders forwarded them to a survey research firm for recruitment of a matched control participant. More detailed information for each enrolled case was later filled in with additional data from state and local police, medical examiner, emergency medical services, and hospital data sources.15

We pair-matched case participants to control participants on the date and time (within 30-minute intervals; i.e., 10:30 pm, 11:00 pm) of each shooting. This was done because the factors we planned to analyze, including gun possession, were often short-lived making the time of the shooting most etiologically relevant.16 This also helped to control for a great many unmeasurable confounders related to time. We also matched our control participants to case participants on the basis of age group (aged 21–24 years, 25–39 years, 40–64 years, and 65 years and older), gender, and race (Black or White). We pair-matched on these variables to avoid extremely sparse data in certain subgroups given a priori knowledge that exceedingly different age, race, and gender distributions existed among assaultive shootings relative to the general population of Philadelphia.17 We did not pair-match case participants and control participants on location. On the basis of early power calculations, we matched 1 control participant to each shooting case.

Control participants were in Philadelphia at the time their matched case was shot. The median number of days between the time a shooting occurred and the time a control participant interview was completed was 2 days. More than three quarters of all control participant interviews were completed within 4 days of their matched shooting. Control participants were interviewed as rapidly as possible to minimize recall bias.

Control participants were sampled from all of Philadelphia via random-digit dialing.10,18 In the interest of time, multiple interviewers may have simultaneously begun and then completed control participant interviews. This resulted in 7 case participants that had more than 1 control participant. These few additional control participants were retained in final analyses. We also tested for the possibility of unequal sampling by using an inverse probability of selection weight defined as the number of eligible control participants divided by the number of phone lines in a household. These weighted models generated only very small differences (< 5%) in our results.

We took several steps to maximize participation and avoid selection biases caused by nonresponse.15,10,19–21 According to standard formulae, the cooperation rate for our control participant survey was calculated to be 74.4% and the response rate 56.0%.22 These rates exceeded those of other surveys conducted at about the same time23 and were high enough to produce a reasonably representative sample of our target population.24,25 Our control participants were statistically similar to the general population of Philadelphia in terms of marital status, retirement, education, general health status, and smoking status within the age, gender, and race categories specified earlier.26 Our control participants were, however, significantly more unemployed than the general population.

Conceptual Framework and Variables

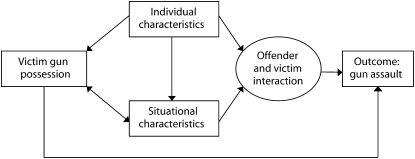

We conceptually separated confounding variables in the association between victim gun possession and gun assault into individual and situational characteristics, both of which feed the eventual victim–offender interaction that results in gun assault (Figure 1).27–29

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework showing the relationships between victim gun possession, gun assault, and other important characteristics.

Case subsets included fatal gun assaults and gun assaults in which the victim had at least some chance to resist the threat posed by an offender, based on circumstance data and written accounts from police, paramedics, and medical examiners. Case participants with at least some chance to resist were typically either 2-sided, mutual combat situations precipitated by a prior argument or 1-sided attacks where a victim was face-to-face with an offender who had targeted him or her for money, drugs, or property. Case participants with at least some chance to resist were in contrast to those that happened very suddenly, involved substantial distances, had no face-to-face contact, and had physical barriers between victim and shooter (e.g., an otherwise uninvolved victim shot in his living room from a gun fired during a fight down the street).30–33 Each case's chance-to-resist status was assigned after being independently rated by 2 individuals (initial κ = 0.64 indicating substantial agreement34) who then reconciled differential ratings.

For case participants, gun possession at the time of the shooting was determined by police observations at crime scenes and police interviews with victims and witnesses, as well as confiscation and recovery of guns by police investigators. We coded case participants as in possession if 1 or more guns were determined to have been with them and readily available at the time of the shooting. We coded control participants as in possession if they reported any guns in a holster they were wearing, in a pocket or waistband, in a nearby vehicle, or in another place, quickly available and ready to fire at the time of their matched case's shooting. We determined gun possession status for 96.8% of case participants and 99.6% of control participants. We imputed missing data by using multiple imputation by chained equations.35,36

We collected participants' locations as street intersection or blockface points. We collected environmental factors as centroid and population-weighted centroid points of blocks, block groups, and tracts.37 We assigned study participants cumulative, inverse distance-weighted measures of each environmental factor on the basis of the points where they were located and the point locations and magnitudes of the factors surrounding them. The higher the measure, the greater the clustering and magnitude of factors around a participant's location.15,38

Statistical Analyses

We modeled gun possession as the focal independent variable with the outcome of gun assault and other confounding variables by using conditional logistic regression.39 We excluded excessively collinear confounders to keep variance inflation factors less than 10.40

We adjusted all regression models for yearly age (to control for residual variability within age groups that remained after matching17) and numerous other potential individual and situational confounders based on previous work and theory (Table 1).5–8,27,32,33,41–48 We defined workers at high probability of being assaulted based on their profession (e.g., their job involved handling of cash) as being at high risk.46 We calculated reduced regression models with confounders that, when added to the model of gun possession and yearly age, changed the matched odds ratio by more than 15%.49,50 We also calculated full regression models with all confounders that were not excessively collinear regardless of how much they changed the matched odds ratio. Robust sandwich estimators of variance were specified.51 Regression model residuals were not statistically significant for spatial autocorrelation.52,53

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Case and Control Participants, by Situational and Individual Characteristics: Philadelphia, PA, 2003–2006

| All Gun Assaults |

Fatal Gun Assaults |

Gun Assaults Where Victim Had at Least Some Chance to Resist |

||||

| Case Participants (n = 677) | Control Participants (n = 684) | Case Participants (n = 163) | Control Participants (n = 166) | Case Participants (n = 446) | Control Participants (n = 451) | |

| Situational characteristics | ||||||

| Gun possession, % | 5.92 | 7.16 | 8.80 | 7.85 | 8.28 | 7.37 |

| Alcohol involvement, % | 26.34 | 13.82** | 24.55 | 14.20** | 28.94 | 13.58** |

| Illicit drug involvement, % | 11.27 | 7.51** | 23.38 | 4.75** | 9.00 | 8.85 |

| Being outdoors, % | 83.13 | 9.05** | 70.77 | 9.24** | 82.21 | 9.65** |

| Other persons present, mean no. | 3.12 | 2.91 | 3.29 | 2.90 | 3.36 | 2.95 |

| Surrounding area | ||||||

| Blacks, mean 1000 persons per mile | 26.04 | 20.19** | 24.44 | 20.62** | 25.81 | 19.56** |

| Hispanics, mean 1000 persons per mile | 4.50 | 2.68** | 4.21 | 2.89* | 4.65 | 2.68** |

| Unemployment, mean 1000 persons per mile | 2.44 | 1.98** | 2.29 | 2.02** | 2.43 | 1.96** |

| Income, mean million dollars per mile | 594.90 | 652.79** | 577.11 | 632.32 | 586.65 | 660.26** |

| Alcohol outlets, mean no. per mile | 79.87 | 82.12 | 73.05 | 82.42 | 78.48 | 84.28 |

| Illicit drug trafficking, mean arrests per mile | 953.21 | 563.60** | 809.94 | 634.19* | 958.58 | 551.69** |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean, y | 30.56 | 32.65** | 31.99 | 34.12** | 30.88 | 32.84** |

| Black, % | 87.89 | 87.87 | 87.69 | 87.31 | 85.56 | 85.31 |

| Male, % | 91.88 | 91.67 | 91.38 | 91.54 | 94.40 | 94.25 |

| Hispanic, % | 7.15 | 3.51** | 7.63 | 4.23 | 8.12 | 3.82** |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Professional, % | 33.00 | 29.93 | 28.68 | 30.82 | 34.70 | 30.43 |

| Working class, % | 31.34 | 46.70 | 30.77 | 41.39 | 30.49 | 46.40 |

| Not working, % | 35.66 | 23.38 | 40.55 | 27.79 | 34.81 | 23.17 |

| High-risk occupation (those handling cash), % | 24.34 | 11.40** | 13.78 | 10.45 | 27.21 | 10.99** |

| Education, mean y | 11.59 | 12.73** | 11.66 | 12.68** | 11.59 | 12.76** |

| Prior arrests, % | 53.12 | 37.06** | 54.58 | 35.95** | 52.80 | 37.17** |

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01.

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of misclassification bias on our analyses of gun possession and gun assault. To do this we purposely miscoded the gun possession status of case participants and control participants by specifying that a randomly selected 1%, 3%, 5%, and 10% of them had their guns go undetected and then reran our regression models to determine the effect on our original odds ratio. We repeated this procedure 100 times for each percentage combination of miscoded case participants and control participants and averaged the results to produce a mean biased odds ratio and standard error. The 2 misclassification biases upon which we most concentrated were case participants without guns recoded to having guns (e.g., to test the bias of a shooting victim or others on-scene disposing of their guns before police arrived) and control participants without guns recoded to having guns (e.g., to test the bias of having been in possession of a gun but not admitting it to an interviewer). The levels of misclassification we tested were based on prior work54–56 and our own data that indicated less than 1% of our control participants were not “very sure” of their gun possession status. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significance was indicated by P values less than .05 throughout our analyses.

RESULTS

Over the study period, our research team was notified of 3485 shootings of all types occurring in Philadelphia. This translated into an average of 4.77 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.82) shootings per day, with a maximum of 21 shootings in a single day and an average of 9 days a year that were free from shootings. From among all these shootings, 3202 (91.88%) were assaults, 167 were self-inflicted (4.79%), 60 were unintentional (1.72%), 54 were legal interventions (1.55%), and 2 were of undetermined intent (0.06%). When we considered only assaults, an average of 4.39 (SD = 2.70) individuals were shot per day in Philadelphia with a maximum of 20 in a single day and an average of 13 days a year in which no individuals were shot.

From among all 3202 individuals who had been shot in an assault, we excluded those aged younger than 21 years or of unknown age (29.83%), non-Philadelphia residents (4.34%), individuals not described as being Black or White (1.62%), and police officers that had been shot (0.09%). From the remaining group of 2073 participants, we randomly selected and enrolled 677 individuals (32.66%). We also concurrently identified and enrolled an age-, race-, and gender-matched group of 684 control participants.

Case participants and control participants showed no statistically significant differences in age group, race, and gender distributions, or in the times of day, days of the week, and months of the year when their data were collected. Case participants and control participants were thus successfully matched on age category, race, gender, and time.

However, compared with control participants, shooting case participants were significantly more often Hispanic, more frequently working in high-risk occupations1,2, less educated, and had a greater frequency of prior arrest. At the time of shooting, case participants were also significantly more often involved with alcohol and drugs, outdoors, and closer to areas where more Blacks, Hispanics, and unemployed individuals resided. Case participants were also more likely to be located in areas with less income and more illicit drug trafficking (Table 1).

Association Between Gun Possession and Gun Assault

After we adjusted for confounding factors, individuals who were in possession of a gun were 4.46 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.16, 17.04) times more likely to be shot in an assault than those not in possession. Individuals who were in possession of a gun were also 4.23 (95% CI = 1.19, 15.13) times more likely to be fatally shot in an assault. In assaults where the victim had at least some chance to resist, individuals who were in possession of a gun were 5.45 (95% CI = 1.01, 29.92) times more likely to be shot.

When we only considered independent variables that most strongly affected our models, smaller but correspondingly significant adjusted odds ratios were noted. In these reduced models, individuals who were in possession of a gun were 2.55 (95% CI = 1.00, 6.58) times more likely to be shot in an assault than those not in possession. Individuals who were in possession of a gun were also 3.54 (95% CI = 1.18, 10.58) times more likely to be fatally shot in an assault. In assaults where the victim had at least some chance to resist, individuals who were in possession of a gun were 2.92 (95% CI = 1.01, 8.42) times more likely to be shot (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

Regression Results Showing the Association Between Gun Possession and Gun Assault: Philadelphia, PA, 2003–2006

| Total Participants (Cases and Controls), No. | Full Models, AOR (95% CI) | Reduced Models, AOR (95% CI) | |

| All gun assaults | 1361 | 4.46 (1.16, 17.04)* | 2.55 (1.00, 6.58)* |

| Fatal gun assaults | 329 | 4.23 (1.19, 15.13)* | 3.54 (1.18, 10.58)* |

| Gun assaults where victim had at least some chance to resist | 897 | 5.45 (1.01, 29.92)* | 2.92 (1.01, 8.42)* |

Notes. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The full models adjusted for all characteristics listed in Table 1; reduced models adjusted for age, illicit drug involvement, being outdoors, and unemployment.

*P ≤ .05.

Sensitivity analyses produced no odds ratio estimates less than 1.00. If we assumed that both case participants and control participants had 5% of their guns go undetected, the observed odds ratio of 4.46 (significant) would have been reduced to 2.23 (nonsignificant). Similarly, among gun assaults where the victim had a reasonable chance to resist, 5% underdetection of guns among both case participants and control participants would have reduced the observed odds ratio of 5.45 (significant) to 3.12 (nonsignificant; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity Analyses Showing the Effects of Simulated Misclassification Because of Undetected Gun Possession: Philadelphia, PA, 2003–2006

| % of Control Participants Without Guns Randomly Recoded to Having Gunsa | % of Case Participants Without Guns Randomly Recoded to Having Gunsb |

||||

| 0% | 1% | 3% | 5% | 10% | |

| All gun assaults | |||||

| 0% | 4.46* | 4.80* | 5.45* | 6.22* | 8.25** |

| 1% | 3.66 | 3.83 | 4.51* | 5.07* | 6.91** |

| 3% | 2.49 | 2.69 | 3.11 | 3.51 | 4.81* |

| 5% | 1.86 | 2.01 | 2.37 | 2.23 | 3.07* |

| 10% | 1.03 | 1.14 | 1.32 | 1.26 | 1.78 |

| Fatal gun assaults | |||||

| 0% | 4.23* | 4.76* | 5.48* | 6.30* | 8.36** |

| 1% | 3.62 | 3.87* | 4.44* | 5.28* | 7.21* |

| 3% | 2.52 | 2.85 | 3.35 | 3.84 | 4.45* |

| 5% | 1.89 | 2.29 | 2.54 | 2.87 | 4.01 |

| 10% | 1.03 | 1.31 | 1.53 | 1.74 | 2.31 |

| Gun assaults where victim had at least some chance to resist | |||||

| 0% | 5.45* | 4.78* | 5.66* | 6.27* | 8.34** |

| 1% | 3.59 | 4.75 | 5.48 | 6.24* | 8.73* |

| 3% | 2.46 | 3.25 | 3.82 | 4.34 | 6.00* |

| 5% | 1.86 | 2.53 | 2.80 | 3.12 | 4.36 |

| 10% | 1.03 | 1.42 | 1.66 | 1.83 | 2.48 |

For instance, to compensate for control participants who failed to disclose their gun possession.

For instance, to compensate for case participants who discarded their guns after they were shot.

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; base adjusted odds ratio is adjusted odds ratios from full models with 0% of case and 0% of control participants recoded.

DISCUSSION

After we adjusted for numerous confounding factors, gun possession by urban adults was associated with a significantly increased risk of being shot in an assault. On average, guns did not seem to protect those who possessed them from being shot in an assault. Although successful defensive gun uses can and do occur,33,57 the findings of this study do not support the perception that such successes are likely.

A few plausible mechanisms can be posited by which possession of a gun increases an individual's risk of gun assault. A gun may falsely empower its possessor to overreact, instigating and losing otherwise tractable conflicts with similarly armed persons. Along the same lines, individuals who are in possession of a gun may increase their risk of gun assault by entering dangerous environments that they would have normally avoided.58–60 Alternatively, an individual may bring a gun to an otherwise gun-free conflict only to have that gun wrested away and turned on them.

Situations in which the victim had at least some chance to resist may have generated gun assault risks when one considers that many of these events were 2-sided situations in which both parties were ready and mutually willing to fight on the basis of a prior argument.29,30 Because both victim and offender had some sense of each other's capabilities prior to the event they may have had more time to prepare for their ensuing conflict.61 More preparation may have increased the likelihood that both individuals were armed with guns and that at least 1 or both were shot.

Although less prevalent, 1-sided situations in which a victim had at least some chance to resist an unprovoked attack may have also generated gun assault risks for victims who possessed guns.29 In these situations, victim and offender were often interacting for the first time and the element of surprise afforded the offender likely limited the victim's ability to quickly produce a gun and defuse or dominate their advantaged opponent. If the victim did produce a gun, doing so may have simply exacerbated an already volatile situation and gotten them shot in the process.

In contrast, when victims had little to no chance to resist, they were almost always confronted with events that happened very suddenly, involved substantial distances, had no face-to-face contact, and had physical barriers between them and the shooter (e.g., bystander or drive-by shootings). These victims likely had no meaningful opportunity to use a gun even if they had one in their possession.

Prior Case–Control Studies

We endeavored to improve upon prior case–control studies that have explored the relationship between homicide and exposure to guns.5–9 Although gun homicides are important to prevent, the ability to produce a more general conclusion about the risk of gun assault, not simply the risk of being murdered with a gun, was of greater importance to public health and safety. This prompted us to enroll all shootings, regardless of their survival, as one improvement to our case–control study.

A second improvement was our use of an incidence density sampling framework to select control participants. This allowed us to make a judgment about the risk associated with gun possession proximal to the shooting event itself. Prior case–control work has involved less proximal gun exposure measures — owning,9 purchasing,7,8 or having a gun in the home.5,6 These measures leave open to question the actual risk that a gun may pose for an individual concurrent with the time they were shot. That is, someone may have a gun in their home, may have purchased a gun, or may own a gun, but without knowledge of whether that gun was in their possession at the time they were shot, the possibility that they have been misclassified as being exposed to a gun when in fact they were not is a potential bias.43,62,63 This bias erodes the ability to speculate on plausible causal mechanisms other than to say that general access to a gun, over some amount of space or time, is a risk factor.

Finally, as this was a case–control study, we had the advantage of being able to statistically adjust for numerous confounders of the relationship between gun possession and gun assault. These confounders included important individual-level factors that did not change with time such as having a high-risk occupation, limited education, or an arrest record. Other confounders that we included were situational factors that could have influenced the relationship under study: substance abuse, being outside, having others present, and being in neighborhood surroundings that were impoverished or busy with illicit drug trafficking. Although these situational confounders were potentially short-lived (e.g., a participant may have metabolized the drugs or alcohol they consumed, moved to another location, or left the company of others) this was less important given the incidence–density sampling and the fact that case and control participants were essentially matched on time.

Study Limitations

A number of study limitations deserve discussion. Our control population was more unemployed than the target population of Philadelphians that it was to intended to represent. Although we did account for employment status in our regression models and our control population was found to be representative of Philadelphians for 5 other indicators, having a preponderance of unemployment among our control participants may mildly erode our study's generalizability. It is also worth noting that our findings are possibly not generalizable to nonurban areas whose gun injury risks can be significantly different than those of urban centers like Philadelphia.64

Certain other variables that may have confounded the association between gun possession and assault were also beyond the scope of our data collection system and, therefore, were not included in our analyses. For instance, any prior or regular training with guns was a potentially important confounding variable that we did not measure and whose inclusion could have affected our findings (although the inclusion of other confounding variables possibly related to training may account for some of this unmeasured confounding).

We also did not account for the potential of reverse causation between gun possession and gun assault. Although our long list of confounders may have served to reduce some of the problems posed by reverse causation,65 future case–control studies of guns and assault should consider instrumental variables techniques to explore the effects of reverse causation. It is worth noting, however, that the probability of success with these techniques is low.66

Finally, our results could have been affected by misclassification of gun possession status. Because of prior discussion63 and likely levels of misclassification,54–56 we concentrated on undetected gun possession. The ensuing sensitivity analyses demonstrated odds ratio estimates that increased and decreased in statistical significance but that did not drop below 1.00, even when challenged with high levels of misclassification. Thus, even after simulating high levels of misclassification bias, a net protective effect of gun possession was not evident.

Conclusions

On average, guns did not protect those who possessed them from being shot in an assault. Although successful defensive gun uses are possible and do occur each year,33,57 the probability of success may be low for civilian gun users in urban areas. Such users should rethink their possession of guns or, at least, understand that regular possession necessitates careful safety countermeasures. Suggestions to the contrary, especially for urban residents who may see gun possession as a surefire defense against a dangerous environment,61,67 should be discussed and thoughtfully reconsidered.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant R01AA013119).

The authors are also indebted to numerous dedicated individuals at the Philadelphia Police, Public Health, Fire, and Revenue Departments as well as DataStat Inc, who collaborated in this work.

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by both the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health institutional review boards. A federal certificate of confidentiality was also provided by the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Branas CC. A review of: suing the gun industry: a battle at the crossroads of gun control and mass torts. J Leg Med 2006;27(1):103–108 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System: 2000-2001. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed March 1, 2009

- 3.Wellford CF, Pepper JV, Petrie CV. Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005:6 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vizzard W. Shots in the Dark. The Policy, Politics, and Symbolism of Gun Control. New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebe DJ. Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:771–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Rushforth NB, et al. Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1084–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassel KM, Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Romero MP. Association between handgun purchase and mortality from firearm injury. Inj Prev 2003;9:48–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings P, Koepsell T, Grossman D, Savarino J, Thompson R. The association between the purchase of a handgun and homicide or suicide. Am J Public Health 1997;87:974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleck G, Hogan M. National case-control study of homicide offending and gun ownership. Soc Probl 1999;46(2):275–293 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner J, Wiebe DJ, Richmond TS, et al. Reducing firearm violence: a research agenda. Inj Prev 2007;13:80–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poole C. Critical appraisal of the exposure-potential restriction rule. Am J Epidemiol 1987;125:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole C. Exposure opportunity in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123:352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poole C. Controls who experienced hypothetical causal intermediates should not be excluded from case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richmond TS, Branas CC, Cheney RA, Schwab CW. The case for enhanced data collection of gun type. J Trauma 2004;57:1356–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Branas C, Richmond T, Culhane D, Wiebe D. Novel linkage of individual and geographic data to study firearm violence. Homicide Stud 2008;12(3):298–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts I. Methodologic issues in injury case-control studies. Inj Prev 1995;1:45–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Case-control studies. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, eds Modern Epidemiology 2nd ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998:93–114 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waksberg J. Sampling methods for random digit dialing. J Am Stat Assoc 1978;73:40–46 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koepsell TD, McGuire V, Longstreth WT, Jr, Nelson LM, van Belle G. Randomized trial of leaving messages on telephone answering machines for control recruitment in an epidemiologic study. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144:704–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow BL, Crea EC, East MA, Oleson B, Fraer CJ, Cramer DW. Telephone answering machines: the influence of leaving messages on telephone interviewing response rates. Epidemiology 1993;4:380–383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzog A, Rodgers W. The use of survey methods in research on older Americans. Woolson R, ed The Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daves R. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4th ed.Lenexa, KS: The American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:643–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeter S, Kennedy C, Dimock M, Best J, Craighill P. Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opin Q 2006;70:759–779 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groves R. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin Q 2006;70:646–675 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey Adult Respondent File, 2002, 2004, 2006 Philadelphia, PA: Public Health Management Corporation; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegenhagen E, Brosnan D. Victim responses to robbery and crime control policy. Criminology 1985;23:675–695 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felson R, Steadman H. Situational factors in disputes leading to criminal violence. Criminology 1983;21:59–74 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells W. The nature and circumstances of defensive gun use: a content analysis of interpersonal conflict situations involving criminal offenders. Justice Q 2002;19:127–157 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denton JF, Fabricius WV. Reality check: using newspapers, police reports, and court records to assess defensive gun use. Inj Prev 2004;10:96–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfgang M. A tribute to a view I have opposed. J Crim Law Criminol 1995;86(1):188–192 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleck G, DeLone M. Victim resistance and offender weapon effects in robbery. J Quant Criminol 1993;9(1):55–81 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleck G, Gertz M. Armed resistance to crime: the prevalence and nature of self-defense with a gun. J Crim Law Criminol 1995;86(1):150–187 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koepsell TD, Weiss NS. Epidemiologic Methods: Studying the Occurrence of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003:200 [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med 1999;18:681–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie D, Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM. Estimation of the proportion of overweight individuals in small areas - a robust extension of the Fay-Herriot model. Stat Med 2007;26:2699–2715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branas CC, Elliott MR, Richmond TS, Culhane DP, Wiebe DJ. Alcohol consumption, alcohol outlets, and the risk of being assaulted with a gun. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:906–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breslow NE. Statistics in epidemiology: the case-control study. J Am Stat Assoc 1996;91(433):14–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fox J. Regression Diagnostics: An Introduction. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991:7–79 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson DE, Grant-Worley JA, Powell K, Mercy J, Holtzman D. Population estimates of household firearm storage practices and firearm carrying in Oregon. JAMA 1996;275:1744–1749 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleck G, Gertz M. Carrying guns for protection: results from the National Self-Defense Survey. J Res Crime Delinq 1998;35(2):193–224 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleck G. What are the risks and benefits of keeping a gun in the home? JAMA 1998;280:473–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decker S, Caldwell A. Illegal Firearms: Access and Use by Arrestees. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 1997. Report ID NCJ 163496 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow MJ. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Islam SS, Edla SR, Mujuru P, Doyle EJ, Ducatman AM. Risk factors for physical assault. State-managed workers' compensation experience. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warner BD, Wilson Coomer B. Neighborhood drug arrest rates: are they a meaningful indicator of drug activity? A research note. J Res Crime Delinq 2003;40(2):123–138 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleck G, McElrath K. The effects of weaponry on human violence. Soc Forces 1991;69(3):669–692 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:125–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleinbaum DG. Epidemiologic methods: the “art” in the state of the art. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:1196–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White H. A heteroscedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroscedasticity. Econometrica 1980;48:817–838 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Getis A. Spatial statistics. Longley P, Goodchild M, Maguire D, Rhind D, eds Geographical Information Systems Volume 1 Principles and Technical Issues. 2nd ed Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons; 2000:239–251 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gruenewald PJ, Remer L. Changes in outlet densities affect violence rates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006;30:1184–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith T. A seeded sample of concealed-carry permit holders. J Quant Criminol 2003;19:441–445 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rafferty AP, Thrush JC, Smith PK, McGee HB. Validity of a household gun question in a telephone survey. Public Health Rep 1995;110:282–288 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Banton J, et al. Validating survey responses to questions about gun ownership among owners of registered handguns. Am J Epidemiol 1990;131:1080–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hemenway D. The myth of millions of annual self-defense gun uses: a case study of survey overestimates of rare events. Chance 1997;10(3):6–10 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson DC, Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Adams J, Hillman M. Risk compensation theory should be subject to systematic reviews of the scientific evidence. Inj Prev 2001;7(2):86–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peltzman S. The effects of automobile safety regulation. J Polit Econ 1975;83:677–725 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilkinson DL, Fagan J. Role of firearms in violence scripts: the dynamics of gun events among adolescent males. Law Contemp Probl 1996;59(1):55–89 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson DL. Guns, Violence, and Identity Among African American and Latino Youth. New York, NY: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ikeda RM, Dahlberg LL, Kresnow MJ, Sacks JJ, Mercy JA. Studying “exposure” to firearms: household ownership v access. Inj Prev 2003;9(1):53–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cummings P, Koepsell TD. Does owning a firearm increase or decrease the risk of death? JAMA 1998;280:471–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Branas CC, Nance ML, Elliott MR, Richmond TS, Schwab CW. Urban-rural shifts in intentional firearm death: different causes, same results. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1750–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brookhart MA, Wang PS, Solomon DH, Schneeweiss S. Evaluating short-term drug effects using physician-specific prescribing preference as an instrumental variable. Epidemiology 2006;17:268–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Staiger D, Stock J. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 1997;65:557–586 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anderson E. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; 1999 [Google Scholar]