Abstract

Despite efforts to the contrary, disparities in health and health care persist in the United States. To solve this problem, federal agencies representing different disciplines and perspectives are collaborating on a variety of transdisciplinary research initiatives. The most recent of these initiatives was launched in 2006 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Office of Public Health Research and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health brought together federal partners representing a variety of disciplines to form the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research (FCHDR).

FCHDR collaborates with a wide variety of federal and nonfederal partners to support and disseminate research that aims to reduce or eliminate disparities in health and health care. Given the complexity involved in eliminating health disparities, there is a need for more transdisciplinary, collaborative research, and facilitating that research is FCHDR's mission.

“The greatest single challenge facing our globalized world is to combat and eradicate its disparities.”

—Nelson Mandela1

OVER THE LAST FEW DECADES, there has been a dramatic decline in disease mortality for many Americans.2–5 However, some groups of Americans have not fully benefited from this progress, as evidenced by their continued higher disease incidence, morbidity, and mortality.6–9 Racial and ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, women, the medically underserved, and the economically disadvantaged, among others, face many obstacles to accessing and receiving effective health services, such as health promotion, disease prevention, early detection, and high-quality medical treatment.10–12 As a result, many experience suboptimal health outcomes. Barriers to optimum health include inadequate purchasing power; being uninsured and underinsured; geographic, cultural, and language barriers; racial bias; and stereotyping. These factors are key determinants of health disparities.10–13

To better address these determinants, in 2000 the federal government established the elimination of health disparities as a goal of the Healthy People 2010 initiative; as part of this effort, the government made a large investment in research into health disparities and health equity.14–16 Although this work yielded important knowledge about the complex interplay of factors that contribute to health disparities, a midcourse review of Healthy People 2010 showed limited success in reducing health disparities in communities across our nation.17 In recognition of the need for greater success, the absence of a broad collaborative approach across the federal government, and the potential benefits of multiagency collaboration, the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research (FCHDR) was launched in 2006. Given the complexity involved in eliminating health disparities, there is a need for more innovative approaches derived from transdisciplinary research and involving multiple federal agencies from different disciplines.

HEALTH DISPARITIES IN THE UNITED STATES

Health disparities can be defined as significant gaps or differences in the overall rates of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, or survival in a given population compared with the health status of the general population.16 In spite of many improvements in health over the past several decades, racial/ethnic gaps still exist with respect to preventable disease and premature death. For instance, African American and American Indian infant morality rates are 2.5 and 1.5 times higher, respectively, than those for Whites.18 The prevalence of high blood pressure, a major risk factor for coronary heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and heart failure, is nearly 40% greater in African Americans than in Whites.19 Mexican American adults are 2 times more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to have been diagnosed with diabetes by a physician.20 African American women are 34% more likely to die from breast cancer than White women, although African American women are diagnosed with the disease 10% less frequently than White women.21 Asian/Pacific Islander men and women have 3 times the incidence of liver cancer found in non-Hispanic Whites.22

In recognition of the prevalence of such disparities, the limited progress made in addressing them over several decades, and recommendations by policymakers and experts for improved solutions to reduce health disparities, senior scientists and managers involved in forming FCHDR determined that an integrated, coordinated approach to the elimination of health disparities was lacking.14–16,23 These insights led several federal departments and agencies to cooperate in exploring the feasibility of collaborative research as a tool for accelerating progress in the elimination of health disparities.

Many of the past research initiatives to address health disparities were conducted by various agencies within a single federal department, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These initiatives were primarily conducted within the Office of Minority Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health program to address the Healthy People 2010 goal of eliminating health disparities. This program engaged federal, state, and community organizations as partners. Recent findings from this program's work have shown some progress in promoting and implementing effective community health programs.24

In 2000, in response to the passage of the Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act of 2000, the NIH's National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities initiated a coordinated process to develop a strategic plan to establish health disparities research initiatives within each of the NIH institutes and centers.15,16

In 2003, HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson established the HHS Health Disparities Council to serve as a vehicle for coordination and collaboration among HHS agencies working to eliminate health disparities.

In 2003, in collaboration with HHS agencies and nonfederal partners, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality began monitoring and tracking disparities in health care. The agency also began providing a detailed annual examination of disparities among at-risk priority populations in the United States.13

Although each of these initiatives provides important contributions, these federal efforts were primarily coordinated among agencies within HHS. However, the Interagency Committee on Disabilities Research (ICDR)—a federally mandated multidepartment research collaboration that has the resources and infrastructure needed for the effective exchange of information on disability and rehabilitation research activities—engaged other federal departments in their efforts.25 ICDR has served as a model for the development of the FCHDR.

RATIONALES FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION

Working in partnership, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Office of Public Health Research and HHS's Office of Minority Health brought together federal partners representing a variety of disciplines to form the FCHDR. The primary aim was to engage a wide range of federal departments and agencies to create a transdisciplinary, systems-thinking approach to addressing the complex issues that limit individual agency efforts to reduce and ultimately eliminate health disparities.

FCHDR was created as a flexible network with the ability to promote informal and formal collaborations, establish closer bonds between programmatic and research agencies, and facilitate research efforts that can be quickly translated and disseminated to communities and constituents to expand utilization and promote health. The inclusion of agencies both within and outside HHS has always been a fundamental basis of FCHDR's activities. Federal departments whose missions intersect with housing, education, justice, environment, health, and health care have joined in this effort and have committed to work together toward the goal of achieving health equity. This goal is to be achieved by working toward 4 objectives:

Explore the complexity of health disparities elimination and identify new or improved solutions.

Coordinate between federal agencies to support research that will lead to the elimination of health disparities.

Disseminate innovative research to inform and enhance services in key public health areas.

Identify priorities for cross-agency collaborations.

Expanding on the directive included in the Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act of 2000, FCHDR provides federal agencies with an opportunity to work collaboratively to “ensure health disparities research is conducted as an integrated and inclusive field of study, rather than as an aggregate of independent research activities occurring in separate research domains.”11 Given the budget limitations and the challenging economic landscape facing the United States today, a greater effort to coordinate and work across agency agendas and missions is both necessary and critical. Moreover, President Obama called for such collaboration in a memo he signed upon taking office.26

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE AND STRATEGIC APPROACH

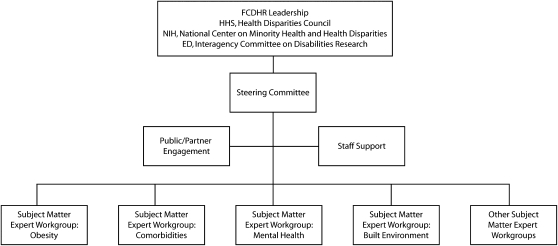

FCHDR focused its early efforts on building an interdisciplinary, cross-agency network that included leadership and scientists from each participating federal agency. Agency leaders provide a governing body for decision making and planning, and subject-matter experts bring an understanding of the best evidence and research needs in the field. FCHDR's formal structure includes colead agencies, a steering committee, subject matter expert workgroups, staff and contractual support, and a network of external partners (Figure 1). Metzger and Zare have argued that enhancement of interdisciplinary research should be owned by several disciplines within an agency or several agencies.27 To this end, the Health Disparities Council within HHS and the ICDR within the National Insititue on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, in the Department of Education, serve as coleads with the NIH's National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, which provides direction for research. The co-lead agencies work together to identify resources, staffing, and support for FCHDR activities. Together these entities provide overall direction and guidance for FCHDR.

FIGURE 1.

Organizational structure of the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research.

Note. HHS = Department of Health and Human Services; NIH = National Institutes of Health; ED = Department of Education.

The FCHDR steering committee is composed of at least 1 champion from each federal department involved in FCHDR's work. FCHDR's steering committee engages subject matter expert workgroups to promote work on research priorities, support research partnerships across departments, and track and report on progress to their respective departments and agencies. Subject matter expert workgroups consist of leading scientific experts who work to advance FCHDR priority research topics by developing research reports, white papers, and journal articles; conducting research workshops to explore research needs; and collaborating with other federal departments and agencies on the development of research concepts for new funding initiatives. A cochair from each subject matter expert workgroup also serves on the FCHDR steering committee. The Office of Minority Health serves as FCHDR's organizational home and provides contract support for ongoing FCHDR activities. Other participating agencies, such as ICDR and NIH, also provide resources. The FCHDR has successfully involved a wide array of partners both within and outside HHS (see the box on the next page); however, expanding and sustaining these partnerships is critical.

Federal Departments and Agencies involved in Forming the Federal Collaboration for Health Disparities Research: United States, 2008–2009

- Department of Health and Human Servicesa

- –Administration for Children and Families

- –Administration on Aging

- –Agency for Healthcare Research and Qualitya

- –Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registrya

- –Centers for Disease Control and Preventiona

- –Center for Medicare and Medicaid Servicesa

- –Food and Drug Administration

- –Health Resource Services Administrationa

- –National Institutes of Healtha

- –Indian Health Servicea

- –Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administrationa

Department of Agriculturea

- Department of Commerce

- –Census Bureau

Department of Housing and Urban Developmenta

- Department of Labor

- –Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Department of Transportation

- –National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

Environmental Protection Agencya

US Agency for International Development

Agencies that participated in meetings or responded to communication requests in 2008 and 2009.

A key approach to FCHDR's work is the promotion of jointly sponsored funding opportunity announcements for research grants or contracts. Some of this promotion is accomplished through regulatory reviews and programmatic evaluations. To ensure the success of joint funding opportunity announcements, research agencies will need to collaborate with agencies that provide services to populations affected by health disparities (e.g., the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Indian Health Service, and the Department of Veterans Affairs). Interagency agreements will need to be developed to clarify relationships, roles, and support responsibilities among partnering agencies. This team approach will help ensure that research findings that promote health equity are translated into effective programs and are disseminated to the agencies and partners that can most benefit from these collaborative efforts. In addition, given that health disparities are known to be rooted not only in individual factors but also in external factors (social, political, and physical contexts),28 agencies whose missions address external determinants are also engaged (e.g., the departments of Housing and Urban Development, Justice, Transportation, and Education).

By building on multiagency partnerships and common research priorities, FCHDR partners can work together to fund collaborative and interdisciplinary research that should result in more effective use of limited resources and reduce redundancy across the federal government.29 Funding opportunity announcements developed collaboratively will help leverage and pool resources to fund more research that addresses complex, multidimensional problems of interest to multiple FCHDR agencies, whether they do research or implement programs and policy. Jointly sponsored funding opportunity announcements will help fund innovative projects that have the potential for greater reduction of disparities, if successful—projects that a single agency may be unable or reluctant to support. This collaborative process also engages nontraditional federal partners in health research (e.g., the departments of Transportation, Education, and Justice) and can encourage and support research by underrepresented minority investigators and persons or organizations engaged in delivering and improving services to disadvantaged populations who may not have “traditional” research backgrounds.

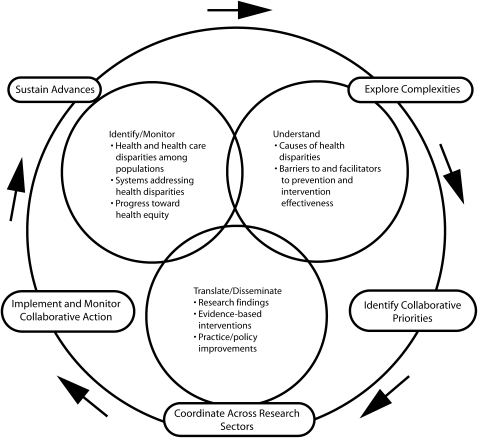

The framework guiding the work of FCHDR comes from a systems-thinking approach that encompasses 3 complex and overlapping activities: identify/monitor, understand, and translate/disseminate (Figure 2). A systems-thinking approach helps move thinking away from a reductionist approach and toward a systems framework in which the interrelatedness of the multiple components involved in the elimination of health disparities are examined, and interagency collaboration and interdependence serve as fundamental drivers.30–32 Systems-thinking approaches expand understanding of the barriers to and facilitators of eliminating health disparities and identify leverage points where interventions may achieve greater success.

FIGURE 2.

Roles played by the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research in achieving health equity.

Note. FCHDR = Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research.

In the FCHDR framework for achieving health equity, the first step is to continue identifying disparities in health and health care, monitor their impact on health and well-being, monitor systems that influence disparities, and track progress toward achievement of health equity. The second step involves furthering our understanding of the root causes of health disparities at all levels, as well as conducting research on the barriers and facilitators to achieving health equity, especially research that addresses prevention of disparities and evaluates intervention effectiveness. The third step is to conduct research that shows how to translate evidence into effective intervention initiatives. Through these research activities, FCHDR will emphasize large-scale interventions based on best available science that promotes innovation, implementation, and sustainability, the outcomes of which will be monitored for quality and modified as needed. Finally, the overall intent of FCHDR is to widely disseminate and implement research findings both directly through the activities of FCHDR and through more service-oriented partners.

These overlapping components of FCHDR's framework are supported by a cyclical set of collaborative processes that include the continual engagement of federal and nonfederal partners throughout all phases. This approach will need careful monitoring via current and new data systems to determine whether FCHDR and other societal efforts have made progress in reducing health disparities and achieving the ultimate goal of health equity.

Drawing on a conceptual model of health disparities proposed by the NIH-funded Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities,28,33 FCHDR works from the understanding that population-based disparities result from complex interactions between and across multiple factors. These factors include, but are not limited to, social conditions and policies, social and physical context, individual demographics and risk behaviors, and biological responses and pathways. By recognizing and creating interventions that address systems of interconnected pathways that lead to health and health care disparities, we may be able to make significant inroads leading to the elimination of health disparities over time.

However, to achieve more disparity reductions, FCHDR will focus on intervention research, which is needed to determine why previously effective interventions might not be working in particular population groups, how interventions can be easily adopted and scaled up to reach more of the targeted populations, and how interventions can be sustained without excessive or additional resource requirements. These high-priority research needs fall within specialized areas of implementation, diffusion, systems, and translation research. Core to these endeavors is community-based participatory research to ensure the active engagement and receptivity needed for success. FCHDR's aim is for successes to generate and accelerate more successes.

To create evidence-based, sustainable programs to eliminate health disparities and promote health equity, research partners must actively disseminate findings, diffuse knowledge, and promote policy changes, both locally and nationally. Although some of these actions may be achievable through research itself, FCHDR will promote and disseminate research findings to all stakeholders, including policymakers, service providers, and the public. FCHDR will write and broadly distribute summary papers promoting FCHDR activities and outputs, research successes, and findings. In addition, FCHDR will facilitate connections between interested parties and experts in the field and will maintain a Web site with content aimed at all stakeholders.

To identify particular needs that might best be addressed by the collaboration, FCHDR will conduct and sponsor literature reviews, webinars, workshops, research symposiums, calls for papers on topic areas, expert panels that incorporate all invested parties (e.g., researchers, service providers, and affected communities), and national meetings and conferences for sharing science and tools for disparities elimination.

EARLY ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND CHALLENGES

Building a supportive and functional structure for collaboration takes time. Many of FCHDR's accomplishments have been organizational, but scientific accomplishments also have been achieved. For example, in early FCHDR meetings, participants identified more than 165 priority research areas relative to eliminating health disparities. Steps for identifying the top 4 priorities involved setting criteria and identifying, categorizing, and prioritizing research topics. To test FCHDR's capacity to move forward, 1 topic from each leading priority group was identified for immediate research collaboration: (1) the relationships between the built environment and the health of vulnerable populations, (2) a systems approach to obesity, (3) quality indicators for persons with multiple chronic health conditions, and (4) effective strategies to increase access to culturally appropriate mental health care services. Experts interested in these areas formed subject matter expert workgroups to develop research concepts and recommendations. The built environment and mental health workgroups report the results of their research collaborations in this issue of the American Journal of Public Health. Drawing from members’ extensive research on health disparities, FCHDR also produced a framework for the collaborative's scientific vision and recommendations.

In order for FCHDR's research to have far-reaching influence, we will need to include nonfederal partners. FCHDR achieved early success in this direction when it convened a nonfederal partners meeting in September 2007. Sixty nonfederal researchers and practitioners from an array of organizations, including state and local health departments, professional associations, universities, nongovernmental organizations, business and worker organizations, community groups, racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaska Native tribal leaders and organizations, and the general public participated in this meeting. Their recommendations have been summarized and will be used to further develop FCHDR research priorities and strategies.

Other early successes included scientific and resource collaboration on funding opportunity announcements,34 as well as focus groups and key informant activities conducted with federal and nonfederal partners to help develop FCHDR's mission, brand, logo, and Web site. The establishment of diversified leadership across 2 separate federal departments has also contributed to FCHDR's success.

FCHDR has also faced a number of early challenges. Some of these challenges are related to raising awareness of potential benefits of collaboration, earning agency trust and interest in a “1 government” approach, and maintaining motivation and involvement of federal agencies in the process of collaboration. FCHDR addressed these challenges through early engagement of senior-level leadership, raising awareness of FCHDR's value, asking senior leadership to identify mid- and senior-level staff to participate in the early planning stages of FCHDR, and maintaining agency and staff commitment to the FCHDR goal. In addition, these strategies facilitated agency ownership and continued involvement in the process.

Other challenges include overcoming resistance that result from bringing together agencies and departments with different missions, mandates, policies, and regulations. FCHDR will continue to address these challenges by consistently communicating its successes, lessons learned, and effective keys to scientific collaboration. FCHDR also will need to improve coordination with the American Indian and Alaska Native Health Disparities Research Advisory Council, to ensure that FCHDR efforts account for the research needs and activities unique to this racial/ethnic group. In addition, other competing work responsibilities sometimes limit federal staff participation, so FCHDR will explore the feasibility of including FCHDR responsibilities in staff performance plans.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATION

Ultimately, FCHDR's success will depend upon how well it recognizes and addresses the barriers to successful research collaboration.27 To that end, FCHDR will perform the following tasks on an ongoing basis:

Create and maintain buy-in at the top. FCHDR leadership will need to work continually with the leadership of federal departments and agencies to improve and maintain agency support and to ensure that senior leadership in each agency are kept informed of FCHDR activities and continue to support them.

Respect agency missions. FCHDR will need to maintain equitable agency representation on the FCHDR steering committee to ensure that agency missions and priorities are respected.

Create common language. Developing a common language for FOAs and other cross-agency initiatives will help federal partnerships operate effectively and allow members to share their expertise.

Build on existing groups. FCHDR will need to position itself to network with other groups that focus on health disparities issues, needs, and program interventions. These efforts help minimize duplication and promote efficiency.

Address support needs as they arise. Colead agencies will need to work together to provide logistical support to maintain momentum, productive networking, and innovation.

Provide infrastructure for collaboration. FCHDR needs to maintain participant engagement and success by continuing to provide the technical support currently available, including online networking—an interactive community workspace where documents, calendars, and interactions are maintained and archived.

Establish an identity. A unique identity and brand will increase recognition and understanding of FCHDR and how it relates to the work of others. Planned improvements to FCHDR's Web site will increase federal and nonfederal partners’ access to FCHDR information.

Overcome future barriers. Proactive efforts by colead agencies and the steering committee will help maintain a structure to address and resolve new issues as they arise.

CONCLUSION

FCHDR intends to accelerate the reduction in US health disparities through effective, ongoing collaboration. The reduction and elimination of disparities requires not just the identification of problems and barriers, but also an appreciation of the critical roles that individuals, agencies, and communities have to play. To achieve equity, we need to accept, promote, and harness the unique assets of all interested parties.

The ongoing work of FCHDR includes developing and strengthening partnerships, identifying new and improved solutions, promoting research translation to enhance effective interventions, influencing policy and practice, and reducing and eliminating health disparities. FCHDR's uniqueness resides in its ability to engage a diverse array of federal and nonfederal partners, leverage limited resources, integrate research with practice, promote effectiveness and efficiency, and develop new multiagency or “1 government” approaches. The linkage between research, practice, and program will accelerate dissemination and implementation of new findings for greater, timelier impact on the public's health. This is no small or simple undertaking. The very strength of the FCHDR comes from the different perspectives, extensive experience, and subject-matter expertise among its membership. None of this can be achieved without networking beyond the federal government to include organizations and stakeholders that address or represent affected populations. The ultimate goal is to achieve health equity by closing gaps in health and health care that exist among populations experiencing health disparities in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Jane Daye and Hazel Dean, ScD, MPH, Eduardo J. Simoes, MD, MSc, MPH, Karen Bouye, PhD, MS, MPH, and Joyce Buckner-Brown, PhD, MHS, RRT contributed to the development of this article by participating in discussions and sharing their knowledge, perspectives, and expertise.

Human Participant Protection

No human research participants were involved in this endeavor.

References

- 1.Mandela N.A great man before a great audience. Transcript of an address given at Harvard University; September 18, 1998; Cambridge, MA. Harvard Magazine. Available at: http://harvardmagazine.com/1998/11/jhj.mandela.html. Accessed July 7, 2009.

- 2.Jemal A, Ward E, Hao Y, Thun M. Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002. JAMA 2005;294:1255–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1998;339(13):861–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin 2003;53:5–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palella FJ, Baker R, Moorman AC, Chmiel JS, Wood KC, Brooks JT. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43(1):27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National diabetes fact sheet, 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2009

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(39):1073–1076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Cancer Statistics Working Group United States cancer statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/uscs. Accessed July 2, 2009

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health, United States, 2005 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mead H, Cartwright-Smith L, Jones K, Ramos C, Woods K, Siegel B. Racial and ethnic disparities in US health care: a chartbook. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm&doc_id=672908. Accessed July 7, 2009

- 11.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds Unequal treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Washington, DC: Academy Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance Board of Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National healthcare disparities report. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr07/nhdr07.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2009

- 14.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health 2nd ed Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institutes of Health Strategic research plan and budget to reduce and ultimately eliminate health disparities Volume 1, 2002–2006 Available at: http://ncmhd.nih.gov/our_programs/strategic/pubs/VolumeI_031003EDrev.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act of 2000, 42 USC §287 (2000). Available at: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/ocga/laws/PL106_525.asp. Accessed July 7, 2009

- 17.Healthy People 2010 Midcourse Review Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2005 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2008;57(2):Table 6. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_02.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: US trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of medicare coverage. Ann Intern Med 2009;150(8):505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Health United States, 2008. Table 54 with special feature on the health of young adults. Hyattsville, MD; 2009:276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dignam J. Differences in breast cancer prognosis among African American and Caucasian women. CA Cancer J Clin 2000;50:50–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute SEER Stat Fact Sheets. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html. Accessed June 15, 2009

- 23.Kennedy E. The role of the federal government in eliminating health disparities. Health Aff 2005;24(2)452–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention REACH US Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/reach/index.htm. Accessed July 7, 2009

- 25.Interagency Committee on Disability Research Web site. Available at: http://www.icdr.us. Accessed July 7, 2009.

- 26.Obama B. Memorandum for the heads of executive departments and agencies. Subject: transparency and open government. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/TransparencyandOpenGovernment. Accessed April 2, 2009

- 27.Metzger N, Zare RN. Interdisciplinary research: from belief to reality. Science 1999;283(5402):642–643 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artinian NT, Warnecke RB, Kelly KM, Weiner J, Lurie N, Flack JM. Advancing the science of health disparities research. Ethn Dis 2007;17(3):427–433 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordan PJ, Ory MG, Sher TG. Yours, mine, and ours: the importance of scientific collaboration in advancing the field of behavior change research. Ann Behav Med 2005;29(suppl 2):7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, Clark PI, Gallagher RS, Marcus SE. Systems thinking to improve the public's health. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(2S):S196–S203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons MC, Brock M, Alberg AJ, Glass T, LaVeist TA, Baylin S. The sociobiologic integrative model (SBIM): enhancing the integration of sociobehavioral, environmental, and biomolecular knowledge in urban health and disparities research. J Urban Health 2007;84:198–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payne-Sturges D, Zenick H, Wells C, Sanders W. We cannot do it alone: building a multi-systems approach for assessing and eliminating environmental health disparities. Environ Res 2006;102:141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, Gehlert S, Paskett E, Tucker KL. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1608–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Elimination of health disparities through translation research (RS-18). Request for applications Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-CD-08-001.html. Accessed July 7, 2009