Abstract

Objectives. We examined universal preventive intervention effects on adolescents' exposure to opportunities for substance use and on illicit substance use in the long term.

Methods. Public schools (N = 22) were randomly assigned to the Iowa Strengthening Families Program (ISFP) or a control condition. We used odds ratio (OR) calculations and structural modeling to test the effects of the ISFP in the 6th grade on exposure to substance use across adolescence, as well as on 12th-grade illicit substance use occurring via reductions in exposure.

Results. The ISFP was associated with reduced exposure to illicit substance use (1.25 ≤ OR ≤ 2.37) that was, in turn, associated with reduced 12th-grade substance use (2.87 ≤ OR ≤ 6.35). The ISFP also reduced the rate of increase in exposure across adolescence (B = −0.37; P < .001), which was associated with the likelihood of 12th-grade illicit substance use (B = 0.30; P = .021), with a significant indirect effect (B = −0.11; P = .048).

Conclusions. The ISFP in the 6th grade reduced substance use through a “protective shield” of reduced exposure. The relative reduction rate was 49%, which suggests that universal prevention shields can contribute to significant reductions in illicit substance use among adolescents.

It is well-documented that problem behaviors in youth are prevalent,1,2 interfere with positive development, and have substantial health, social, and economic consequences in adulthood.2–5 For these reasons, the US Public Health Service's Healthy People 2010 initiative aims to reduce these problem behaviors of youth.6 Epidemiologic study of the factors influencing the onset of the problem behaviors targeted by Healthy People 2010 suggests that developmental windows of opportunity exist for prevention of these problems. For preventing substance dependence and abuse, early adolescence is a critical period during which several vectors of influence encourage substance use. Delaying the age of initiation is associated with reduced future substance-related problems.7,8 Thus, the period of early adolescence offers prime opportunities for preventive intervention.

The conceptualization of a protective shield as a preventive effect has its basis in infectious disease epidemiology.9 In that context, a protective shield entails nonspecific mechanisms that shield a potential host from contact with a pathogen. Chen et al.9 and Anthony10 liken this type of effect to a “second skin” that enhances protection against a broad range of ambient pathogens. With respect to the prevention of substance use disorders, this corresponds to environmental factors and host behaviors that can shield an individual from exposure to tangible agents in the etiology of substance use.

Research has identified factors that increase the likelihood of exposure to opportunities to use substances and has shown that such exposures increase the probability of use.9,11–13 Several factors associated with decreased exposures either originate in the family (e.g., effective parenting practices) or are influenced by family functioning, with one example of the latter being association with deviant peers.14–16 For example, parents who are involved with their adolescents and monitor activities with peers reduce the likelihood of association with deviant peers and generally decrease opportunities to use illicit drugs, thus providing a protective shield. Other factors previously found to be associated with exposure opportunities include the behavioral repertoires of youth, some of which are positively affected by effective parenting.9 For instance, youth prosocial involvements with parents or other adults, as well as with peers, have been linked with decreased exposures to substance use.9,16 Such exposures have been associated with the use of illicit substances such as marijuana.15 Furthermore, use of one type of illicit substance, such as marijuana, is associated with an increased likelihood of exposure to other types of illicit substance use.17,18

Here we examined how universal preventive interventions may convey a shielding effect for general populations of youth by reducing exposure to illicit substance use and thereby reducing long-term substance use outcomes. Central to this conceptualization was the idea that developmentally well-timed interventions for general populations (also labeled “universal interventions”) can impact youth environments and behaviors that, in turn, can shape the key vectors of influence on the initiation of substance use. In this manner, preventive interventions could establish vectors of influence that compete with environmental factors that would otherwise increase exposure to substance use in the absence of intervention.

By design, universal interventions aim to (1) positively alter the primary socializing environments for youth, namely, home and school (e.g., increase parental monitoring), and (2) positively change youth's behavioral repertoire (e.g., prosocial involvement with family and peers, social skills) that also affect contact with substance use agents.7,16 Consistent with the etiologic literature cited above, universal interventions can, thereby, convey a shielding effect through proximal outcomes that mitigate against exposure to substance use. Research indicates that universal preventive interventions have been successful in achieving such effects that could shape these vectors of influence.19 For example, the intervention in the present study has shown positive effects both on parenting practices, including youth monitoring and involving youth in prosocial activities, and on youth skills, such as increasing resistance to substance use opportunities offered by peers.20–23

Previous work by our team has evaluated point-in-time substance use outcomes at 10th grade24 and growth of lifetime use through 12th grade.25 However, the ability of the interventions to produce protective shield effects, indicated by reduced exposures to substance use, had not yet been examined, nor had analyses tested long-term intervention effects on lifetime illicit substance use through late adolescence. We chose 12th-grade overall illicit substance use as the outcome in this research for several reasons, in addition to the fact that it had not been examined previously. First, epidemiologic data indicate considerable prevalence rates among adolescents; in 2007, 49.1% of high school seniors reported lifetime use of at least one illicit drug.1 Second, illicit substance initiation is particularly useful to examine as an illustration of a protective shield effect because the base rates for use are very low through early adolescence and do not markedly increase until an age well beyond the time at which the intervention considered in this report was implemented.26 That is, in the current study, there clearly was sufficient time for the hypothesized protective shield effect to materialize between the 6th-grade intervention implementation and the typical time of initiation in the 8th to 10th grades.25

To examine protective shield effects, we tested 2 hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that a family-focused universal preventive intervention, delivered via a community-university partnership, would result in fewer illicit substance exposures during adolescence, tantamount to a protective shield effect. Second, we hypothesized that the protective shield effect of reduced exposures associated with the universal intervention would predict a lower rate of lifetime illicit substance use at 12th grade.

METHODS

Families of 6th graders enrolled in 22 rural Iowa schools were recruited in 1993. Schools were selected on the basis of school lunch program eligibility (> 15%) and community size (population < 8500). Schools were stratified on the basis of school lunch program eligibility and size and were then randomly assigned to either the Iowa Strengthening Families Program (ISFP) or a control condition. [An additional intervention, the Preparing for the Drug Free Years program (PDFY), was implemented, but no data pertaining to that intervention are presented here. The PDFY results were omitted because to examine the mediational role of protective shield effects, it is necessary for an intervention to be associated with reduced late adolescent illicit substance use, which PDFY was not. Note, however, that PDFY has shown effects on alcohol and tobacco use at various points in time.] Of 846 families recruited, 446 (53%) completed pretesting. The sample was representative, as established by a survey administered approximately 6 months before pretest recruitment began that was completed by 91% of the families in the sampling frame.27

Detailed information on participation in the intervention and assessments is available elsewhere.28 Families averaged 3.1 children, were primarily dual-parent families (86%), had an average household income of $40 600, and were nearly all White (98%).

Adolescents and their parents were interviewed in their homes by project staff members who administered confidentially and independently completed written questionnaires, which required 60 to 80 minutes to complete. Six waves of assessments were conducted: fall and spring of 6th grade and one in grades 7, 8, 10, and 12.

Iowa Strengthening Families Program Intervention

The intervention was administered in cooperation with public school districts and the university extension system, the outreach arm of the land grant university conducting this study. Previous reports have summarized this partnership approach and have shown its association with high-quality intervention implementation.29–32 After pretesting, the intervention was implemented by trained facilitators in the evenings in local schools. Trained observers assessed average adherence to intervention content as being greater than 85%. Forty-nine percent of pretested families attended the intervention, with 94% of those attending 5 or more sessions. These rates compared favorably to similar interventions.33

The ISFP focuses on empirically supported family risk and protective factors, such as parental nurturing, child management skills, and involvement in family activity, along with adolescent social skill development.34 The salient features of the program are summarized in Table 1. Previous reports have provided detailed program descriptions.34,35

TABLE 1.

Key Features of the Iowa Strengthening Families Program Competency-Training Preventive Intervention

| Program Feature | Iowa Strengthening Families Program |

| Theoretical basis | Biopsychosocial model and related risk/protective factor models (Molgaard et al.22) |

| Objectives | To enhance family protective and resiliency processes and to reduce family-based risk factors associated with child behavior problems |

| Program length | Program includes 7 sessions conducted once per week for 7 wk. The first 6 sessions included 1 h of separate parent and child training and 1 family h. The 7th session included only 1 family h. |

| Child involvement | Children and parents attend each session. |

| Program content | Parents are taught to clarify expectations (based on developmental norms), use appropriate disciplinary practices, manage strong emotions regarding their child, and effectively communicate with their child. Children's session content parallels relevant parent sessions content but also includes peer resistance and peer relationship skills training. During family sessions, members practice problem solving/conflict resolution and communication skills and engage in activities designed to increase family cohesiveness and positive involvement of the child in the family. |

| Videotape use | Videotapes to standardize delivery of content |

| Group size | 21 three-person teams conducted 21 groups in 11 schools assigned to the ISFP. Groups averaged 8 families. |

| Attendance rates | 94% of attending families were represented by a family member in 5 or more sessions, 88% attended 6–7 sessions, and 62% completed all 7 sessions |

Note. ISFP = Iowa Strengthening Families Program.

Source. Spoth R, Reyes ML, Redmond C, Shin C. Assessing a public health approach to delay onset and progression of adolescent substance use: latent transition and loglinear analyses of longitudinal family preventive intervention outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:619–630.

Study Measures

The illicit substance use exposure measure included 6 items that tapped 2 kinds of exposure to opportunities to use. Three items tapped general occasions or opportunities to use, asking “During the past 12 months, did you ever have a chance to…” (1) “try marijuana,” (2) “try other drugs, such as cocaine or crack,” and (3) “sniff glue or inhalants to get high?” Responses were dichotomously scored (0 = no, 1 = yes) and then summed, adding 1 to yield a score between 1 and 4. The other 3 items concerned specific offers of opportunities to use by peers, asking “How often do your friends try to get you to…” (1) “use marijuana or pot,” (2) “use illegal drugs other than marijuana (e.g., meth, crack, LSD, speed, etc.),” and (3) “sniff glue for fun or to get high?” Item response options were scored (1 = never to 4 = often) and were averaged to yield a score between 1 and 4. The ultimate illicit substance use exposure score was calculated by averaging the scores of the general and friend-specific items, producing a score that could range from 1 to 4. The correlation between the 2 sets of items averaged 0.42 across 5 waves of data, indicating that the item sets captured related but nonidentical aspects of illicit substance use exposures, thereby providing a more comprehensive measure than would be the case if just one set of highly similar items were used.

Because longitudinal assessments occurred at intervals averaging as much as 18 months, a dichotomous lifetime use measure was judged to be the most appropriate. This measure has a clear-cut yes or no response format that captures use outside of preset time windows (e.g., past month) and avoids the imprecision of attempting to estimate either amount or frequency of consumption. Further desirable characteristics include the measure's relatively accurate indication of a qualitative change in substance use status. The measure consisted of the 2 lifetime illicit substance use items available at the 12th-grade assessment, including “Have you ever…” (1) “used marijuana” and (2) “sniffed glue, or used any drugs (for example, used meth, cocaine, LSD, etc) to get high?” Students were scored zero until the time at which they first reported use of either 1 of these 2 items and were scored as 1 thereafter.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses used as much data as were available for each particular analysis from all assessed participants, including not only those who had fully participated in all intervention sessions but also those who had attended only a subset of sessions or no sessions.

Odds ratios: bivariate relationships.

As detailed in the introduction, the hypothesized chain of outcomes to be tested was that ISFP promotes protective shield effects, as reflected by reduced illicit substance use exposures, which, in turn, decrease the likelihood of illicit substance use. A series of odds ratio analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) PROC GLIMMIX to provide preliminary tests of the 3 bivariate relationships entailed by the hypothesized sequence of effects. The odds ratio analyses also were useful for presenting the results in a straightforward fashion, in terms of numbers of adolescents who did and did not exhibit a change with regard to either illicit substance use exposure or illicit substance use initiation status across a specific period of time. Statistical significance was calculated by using one-tailed probabilities, which was supported by the fact that ISFP consistently has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing both substance use and its associated risk factors, with no negative effects across 5 waves of data and a wide range of outcomes, up to 6 years past baseline, therefore making it reasonable to expect no appreciable iatrogenic or other negative effects in the current analysis. Nonetheless, specific P values are provided so that 2-tailed results are transparent. Each odds ratio analysis included data from all adolescents who provided valid data for the variables required for that particular analysis. These same adolescents may not have provided the data necessary for inclusion in the other odds ratio analyses. This strategy maximized the number of adolescents included in each particular odds ratio analysis, but also caused the numbers of included adolescents to be unequal across odds ratio analyses.

Growth curve model: mediation.

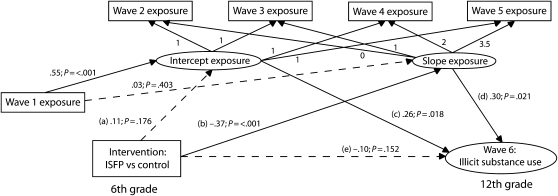

The growth curve model depicted in Figure 1 was used to formally test the mediation hypothesis, namely that ISFP intervention effects on lifetime illicit substance use initiation status at wave 6 would be mediated by protective shield effects, as captured by illicit substance use exposures. The growth of illicit substance use exposures was modeled as linear across the postintervention period, with the intercept set at wave 2. In this manner, the intercept value corresponded to the initial level of exposure estimated by the model to exist immediately after the intervention, and the slope value was the estimated rate of increase in exposures across the postintervention time period of the study. As shown, the model accounted for the potential influence of preintervention exposure opportunities on the postintervention illicit substance use growth factors.

FIGURE 1.

Protective shield growth model used to formally test the mediation hypothesis: Project Family, Iowa, 1993–2000.

Note. ISFP = Iowa Strengthening Families Program. For the paths representing direct effects, the solid and dashed lines denote significant and nonsignificant effects, respectively. Mediated effects correspond to the specific indirect effects of the intervention on wave 6 illicit substance use via the 2 illicit substance use exposure growth trajectory factors and are calculated as a × c = 0.03 (P = .180) and b × d = −0.11 (P = .048).

Most central to the purpose of this paper, the influence of the ISFP intervention (versus control) was incorporated via the inclusion of intervention direct effects on both the intercept (path a) and slope (path b) factors that modeled illicit substance use exposure, as well as by the inclusion of a direct effect on the illicit substance use outcome (path e). In turn, the model included direct effects of the illicit substance use exposure growth factors on the illicit substance use outcome (paths c and d). Thus, the model implicitly provided for a test of the hypothesis that changes in illicit substance use exposure mediate ISFP intervention effects on illicit substance use. Specifically, the mediation hypothesis was tested by evaluation of the significance of the indirect effects of the ISFP on the illicit substance use outcome through the illicit substance use exposure growth factors. [Testing the significance of the specific indirect effects has been mathematically proven to provide a test of the mediation hypothesis.36 In addition, this method has several advantages over techniques involving multiple regression equations, including the ability to simultaneously include multiple mediators, yielding estimates of the mediated effect and provision of standard errors, thereby providing a means of directly assessing statistical significance.37] As depicted in Figure 1, 2 specific indirect effect pathways link ISFP intervention effects to illicit substance use, these being the compound paths ac and bd. Moreover, the magnitudes of these specific indirect effects are equal to the products of the path coefficients, or a × c and b × d. Evaluating the significance of these specific indirect effects tests the mediation hypothesis. As was the case for the OR analyses, the hypothesized model entailed directional predictions and the results were evaluated by using one-tailed statistical tests, with specific P values enabling comparison with 2-tailed tests.

Growth curve analyses were conducted in Mplus 4.138,39 by use of the robust maximum likelihood estimation and full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimates to address incomplete or missing data.40 The use of FIML maximized the use of the data available for estimating the growth curve parameters by including data from every adolescent who provided information on any relevant variable at any assessment wave, thereby providing some information for model estimation. Ultimately, this yielded a total of 446 adolescents in the analysis, including 238 in the ISFP condition and 208 from the control condition. Hierarchical growth curve modeling was used to account for the clustering of adolescents within schools. Data were acquired from assessments made across the years spanning middle school and high school, during which time adolescents switched not only homerooms across years, but also classrooms and classmates within each school day. Therefore, adolescents were not clustered into particular classrooms in these data.

RESULTS

Detailed descriptions of the tests conducted to establish pretest equivalence are provided in earlier reports that documented the equivalence of the intervention and control conditions with respect to family sociodemographic characteristics.19,23 For the current study, pretest equivalence also was established for the illicit substance use exposure and illicit substance use outcome variables.

To assess differential attrition across the experimental conditions, 2-factor analyses of variance were conducted for intervention-control comparisons with the exposure and illicit substance use outcome measures. No significant condition × attrition interaction effects were found for the variables between the 6th-grade pretest and the 12th-grade follow-up. In addition, attrition analyses found no differences in the pretest variables between those who dropped out of the study compared with those who returned across waves.

Odds Ratio Tests of Intervention and Protective Shield Effects

Our analyses initially focused on the first link of the hypothesized chain of effects by testing the relationship between the ISFP and protective shield effects. The results in the upper portion of Table 2 show that at each of the 3 later waves of postintervention assessment, control condition adolescents experienced more illicit substance use exposure than did ISFP condition adolescents. Although this difference was not significant at wave 3 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.78, 2.00; P = .180), it became larger and significant at wave 4 (OR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.70; P = .014) and wave 5 (OR = 2.37; 95% CI = 1.49, 3.76; P < .001).

TABLE 2.

Odds Ratio Analyses of Intervention Effects on Protective Shield and 12th-Grade Illicit Substance Use: Project Family, Iowa, 1993–2000

| Predictor Variable |

Analyses |

|||

| Control, No. (%) | ISFP, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Intervention effects on protective shield at waves 3, 4, and 5a | ||||

| Illicit substance use exposure, 7th grade (wave 3) | 54/156 (34.6) | 48/161 (29.8) | 1.25 (0.78, 2.00) | .180 |

| Illicit substance use exposure, 8th grade (wave 4) | 70/141 (49.6) | 56/152 (36.8) | 1.69 (1.06, 2.70) | .014 |

| Illicit substance use exposure, 10th grade (wave 5) | 89/151 (58.9) | 57/151 (37.7) | 2.37 (1.49, 3.76) | < .001 |

| Intervention effect on lifetime illicit substance use, 12th grade at wave 6a | 47/156 (30.1) | 23/148 (15.5) | 2.34 (1.34, 4.12) | .002 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; ISFP = Iowa Strengthening Families Program; OR = odds ratio. Baseline data were initiated in 1993. Data from successive multiple waves were collected from 1994-2000. Illicit substance use exposures were assessed at multiple waves. Thus, odds ratio analyses that involved illicit substance use exposures yielded multiple odds ratios, one for each wave of illicit substance exposure opportunity examined. The number of adolescents included in each analysis (i.e., the sum of the denominators in each odds ratio analysis) did not always equal the number of adolescents who completed survey assessments at the corresponding waves because sometimes those completing an assessment did not provide valid data for the particular variables pertaining to illicit substance use exposure or lifetime illicit substance use.

Dependent variable.

As presented in the bottom portion of Table 2, control condition adolescents were more likely to have initiated illicit substance use by the end of the study than were ISFP condition adolescents (OR = 2.34; 95% CI = 1.34, 4.12; P = .002).

Consistent with the protective shield hypothesis, the results provided in Table 3 indicate that greater lifetime illicit substance use at wave 6 (at the end of the study) was predicted by illicit substance use exposure assessed at wave 3 (OR = 2.87; 95% CI = 1.60, 5.13; P < .001), wave 4 (OR = 5.48; 95% CI = 2.84, 10.59; P < .001), and wave 5 (OR = 6.35; 95% CI = 3.18, 12.69; P < .001).

TABLE 3.

Odds Ratio Analyses of Protective Shield Effects on Illicit Substance Use: Project Family, Iowa, 1993–2000

| Predictor Variable |

Analyses |

|||

| Dependent Variable | Exposed to Illicit Substance Use Opportunities, No. (%) | Not Exposed to Illicit Substance Use Opportunities, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Illicit substance use by 12th grade (wave 6), predicted by illicit substance use exposure in 7th grade (wave 3) | 33/88 (37.5) | 31/179 (17.3) | 2.87 (1.60, 5.13) | < .001 |

| Illicit substance use by 12th grade, predicted by illicit substance use exposure in 8th grade (wave 4) | 44/113 (38.9) | 15/144 (10.4) | 5.48 (2.84,10.59) | < .001 |

| Illicit substance use by 12th grade, predicted by illicit substance use exposure in 10th grade (wave 5) | 50/132 (37.9) | 12/137 (8.8) | 6.35 (3.18,12.69) | < .001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Baseline data were initiated in 1993. Data from successive multiple waves were collected from 1994-2000. Illicit substance use exposure was assessed at multiple waves. Thus, odds ratio analyses that involved illicit substance use exposure yielded multiple odds ratios, one for each wave of illicit substance exposure opportunity examined. Each odds ratio analysis included all youths who provided valid data for both illicit substance use by 12th grade as well as for substance use exposures at the relevant wave. Because these analyses addressed only the bivariate relationship of substance use exposures to illicit substance use, analyses included data from youths in both the intervention and the control conditions.

To summarize, the odds ratio analyses described above provided a consistent pattern of evidence suggesting that not only did the ISFP prevent illicit substance use but, more specifically, the ISFP promoted protective shield effects—as indicated by less illicit substance use exposure—and, thereby, prevented illicit substance use initiation among high school seniors.

Although the odds ratio results were compelling in their consistency, it was important to consider a developmental perspective in examining how the ISFP affected illicit substance exposure across the adolescent developmental period, when such exposure is most likely to first occur. In addition, it was also necessary to directly test the mediational role of illicit substance use exposure in conveying the effect of the ISFP on illicit substance use and to account for the hierarchal structure of the data.41 We addressed these issues through a multilevel structural equation growth curve model that simultaneously tested multiple direct and mediated effects while accounting for the hierarchical structure of the data by defining schools as clusters.

Growth Curve Model Tests of Direct and Mediated Effects

The results indicated a good model fit (χ29 = 5.02; P = .833). The results for the model's direct effects are presented in Figure 1.

With respect to the particular relationships that were the focus of the current investigation, the results indicated that although the ISFP was not related to the illicit substance use exposure intercept value, which was defined as the initial exposure level estimated immediately after the intervention (B = 0.11; P = .176), the ISFP did reduce the slope value, which was defined as the rate at which illicit substance use exposure was estimated to increase across adolescence (B = −0.37; P < .001). These results echoed those of the odds ratio analyses presented above and were consistent with the interpretation that the ISFP promoted protective shield effects.

Regarding the relationship between protective shield effects and substance use, both the intercept and the slope factors for illicit substance use exposure were positively related to illicit substance use in the 12th grade (B = 0.26; P = .018, and B = 0.30; P = .021, respectively). As suggested by the odds ratio results, these results also supported the idea that when effects that are consistent with the presence of a protective shield are observed, adolescents are less likely to use illicit substances.

An analytic advantage of the structural model over the odds ratio analyses was the ability to test the specific indirect effects that capture mediated relationships. The model included 2 compound paths whereby the effect of the ISFP on illicit substance use could be mediated: compound path ac through the intercept factor and compound path bd through the slope factor of illicit substance use exposure. The results did not indicate an effect of the ISFP on illicit substance use via reductions in illicit substance use exposure just after the intervention (B = 0.03; P = .180). Consistent with intervention theory, this is not surprising, considering that the ISFP was not expected to have impacted this variable so immediately after the intervention, nor so early in adolescence when illicit substance use exposure is rare. However, the analyses did reveal a significant indirect effect of the ISFP on decreasing illicit substance use via reductions in the postintervention rate of increase in illicit substance use exposure across adolescence (B = −0.11; P = .048). Thus, this result supported the hypothesis that the ISFP prevented the initiation of illicit substance use through its effect on providing adolescents with a protective shield, which manifested itself, at least in part, by a reduction in the rate of increase in substance use exposure that is encountered even in normative adolescent development. These reduced rates of increase were expected to result in lower levels of exposure at future points in time, as indicated by the odds ratio values in Table 2. It is worthwhile to note that this effect existed in the context of controlling for pretest levels of illicit substance use exposure as well as all other effects of ISFP on illicit substance use, the latter of which were captured by the direct effect modeled by path e, which was not significant (B = −0.10; P = .152).

DISCUSSION

Our results were consistent with the interpretation that the ISFP decreased 12th-grade illicit substance use and that this effect was mediated by reducing the normally observed increase in illicit substance use exposure that occurs throughout adolescence. Thus, our results supported the idea that the ISFP reduced substance use at a distant point in time by providing adolescents with a protective shield against substance use that remained operative throughout a stage of adolescent development critical to the emergence of illicit substance use.

Our findings are consistent with the etiologic research on exposure to substance use cited in the introduction. That is, earlier research on the ISFP showed effects on parenting behaviors, including parental monitoring and involvement, that establish vectors of influence that effectively compete with those that propel adolescents toward illicit substance use, such as illicit substance use exposure. In this connection, Chen et al.9 proposed that particular behaviors of adolescents (e.g., participation in structured, prosocial activities) tend to create contexts wherein interpersonal vectors of influence are controlled, such that contact with persons or situations that facilitate or encourage substance use does not occur. In the current study, the ISFP intervention was designed to favorably shape parenting behaviors, foster positive parent-child relationships, and improve socially skillful child behaviors. Such parenting behaviors would encourage desirable behavioral repertoires among adolescents, if not directly reducing exposure (e.g., parental monitoring that eliminates some exposures directly), thereby producing protective shield effects.

Implications for Public Health Practice and Policy

Our findings suggest the potential public health benefits of scaling up the ISFP and other comparably effective universal interventions. If, for example, the relative reduction rate found in this study were to hold and the intervention were scaled up, for every 100 adolescents initiating illicit substance use in communities not offering the intervention, there could be as few as 51 initiating use in intervention communities, cutting initiation roughly in half for the time frame considered (assuming the intervention participation rates observed in this study). Note, however, that approximately one half of the sample chose not to participate in the intervention, which highlights the challenges of recruiting families into such interventions, and that the ethnic and geographic diversity of the sample was limited, as further discussed below. Nonetheless, the prospect of public health benefits warrants consideration of translating effective universal, family-focused interventions such as the ISFP into widespread public health practice. Woolf,42–44 for example, advocated supportive policy and proportionately more funding for larger-scale quality implementation of scientifically proven interventions on the basis of the public health benefits that would result. Expressed in terms of the protective shield concept discussed earlier, larger-scale quality implementation could better protect the general public from the consequences of illicit substance use, a goal that could be facilitated by an effective intervention delivery model. Several published studies have demonstrated the ability of partnerships between public schools and land-grant university dissemination systems to produce both community-generated resources and sustained high-quality implementation.30–32 In conjunction with partnership-based delivery, prior empirical work suggests that the universal intervention examined here has potential for population-level effects on a range of outcomes.19,23,45–47

Limitations and Future Directions

The generalizability of our results to nonrural and more ethnically diverse populations remains to be examined. Although self-report data may be subject to biases and biochemical corroboration is desirable when feasible,48 several studies have supported the validity of self-report.49–52 It is unlikely that such bias would impact the intervention-control differences reported here, because they likely would have equally influenced students in both conditions, thereby canceling each other out. Also, although the questionnaire items used to measure illicit substance use referred to “other” substances, examples of other substances given did not explicitly reference prescription drug misuse, so respondents may not have considered such use in their responses.

The reader may note that the lifetime illicit substance use rate of 30% in the control condition was markedly less than the national estimate of 49% cited in the Introduction.1 It is possible that the difference was, in part, due to the demographics of the current sample, insomuch as adolescents were typically from white, dual-parent families, all of whom resided in rural communities of a single Midwestern state. It also is plausible that the difference resulted from the fact that the current study used 2 items to assess lifetime illicit substance use, whereas the national survey used many items, asked about more illicit substances, used multiple terms to identify each particular substance, and asked about each substance multiple times, the effect of which would be to increase the probability of obtaining positive responses, thereby increasing lifetime illicit substance use rates. In any case, the results pertaining to intervention effectiveness and the estimates of public health relevance were calculated by comparing lifetime illicit substance use rates in the control and intervention conditions within this study, thus avoiding the possibility that differences between the national rates and rates of the current sample influenced the results or conclusions of this study.

The long-term effects of the ISFP on illicit substance use may have been at least partly produced by the intervention's positive effects on student resistance to use subsequent to encountering one or more opportunities to use. That is, resistance strengthening can serve to reduce the likelihood of substance use initiation after exposures presenting opportunities to use and can thereby act as a second layer of protection, in addition to the protective shield effect.9 Future analyses will evaluate such effects by examining how intervention effects on student's peer resistance skills might add to protective shield effects on distal substance initiation by reducing the probability of transition to use after exposure to illicit substance use has occurred.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grant DA007029 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by grants AA014702-13 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and MH49217-01A1 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by Iowa State University's institutional review board.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. NIH publication 08-6418 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spoth R, Greenberg M, Turrisi R. Preventive interventions addressing underage drinking: state of the evidence and steps toward public health impact. Pediatrics 2008;121(suppl 4):S311–S336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services Research Report Series: Marijuana Abuse. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2005. NIH publication 05-3859 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy The Economic Costs of Drug Abuse in the United States: 1992-1998. Publication no. 190636. Available at: http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov. Accessed June 16, 2008

- 5.National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Abuse and Addiction: One of America's Most Challenging Public Health Problems. Available at: http://www.nida.nih.gov/about/welcome/aboutdrugabuse/index.html. Accessed June 1, 2008

- 6.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Available at: http://web.health.gov/healthypeople/document. Accessed May 29, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anthony J. Selected issues pertinent to epidemiology of adolescent drug use and dependence. Paper presented at: Annenberg Commission on Adolescent Substance Abuse meeting; August 1, 2003; Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 1997;9:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CY, Dormitzer CM, Gutiérrez U, Vittetoe K, González GB, Anthony JC. The adolescent behavioral repertoire as a context for drug exposure: Behavioral autarcesis at play. Addiction 2004;99:897–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anthony JC. Behavioral autarcesis—reprise. Addiction 2004;99:1062–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal A, Grant JD, Waldron M, et al. Risk for initiation of substance use as a function of age of onset of cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use: findings in a Midwestern female twin cohort. Prev Med 2006;43:125–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crum RM, Lillie-Blanton M, Anthony JC. Neighborhood environment and opportunity to use cocaine and other drugs in late childhood and early adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1996;43:155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Etten ML, Neumark YD, Anthony JC. Initial opportunity to use marijuana and the transition to first use: United States. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997;49:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, et al. Drug use opportunities and the transition to drug use among adolescents from the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;90:128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reboussin BA, Hubbard S, Ialongo NS. Marijuana use patterns among African-American middle-school students: a longitudinal latent class regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;90:12–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Influences of parenting practices on the risk of having a chance to try cannabis. Pediatrics 2005;115:1631–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strang J, McCambridge J. Are cannabis users exposed to other drug use opportunities? Investigation of high-risk drug exposure opportunities among young cannabis users in London. Drug Alcohol Rev 2005;24:185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilcox HC, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Exposure opportunity as a mechanism linking youth marijuana use to hallucinogen use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002;66:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spoth R, Redmond C. Project Family prevention trials based in community-university partnerships: toward scaled-up preventive interventions. Prev Sci 2002;3:203–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Huck S. A protective process model of parent-child affective quality and child mastery effects on oppositional behaviors: a test and replication. J Sch Psychol 1999;37:49–71 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Direct and indirect latent-variable parenting outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: extending a public health-oriented research base. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molgaard VM, Spoth R, Redmond C. Competency Training: The Strengthening Families Program for Parents and Youth 10-14. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2000. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin (NCJ 182208) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redmond C, Spoth R, Shin C, Lepper H. Modeling long-term parent outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: one year follow-up results. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:975–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: adolescent substance use outcomes four years following baseline. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:627–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Azevedo K. Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: school-level curvilinear growth curve analyses six years following baseline. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:535–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. Am J Public Health 2000;90:360–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spoth RL, Redmond C, Kahn JH, Shin C. A prospective validation study of inclination, belief, and context predictors of family-focused prevention involvement. Fam Process 1997;36:403–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iowa State University Partnerships in Prevention Science Institute Participation figure. Available at: http://www.ppsi.iastate.edu/publicationsupplements/PF142/ParticipationFigure.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2009

- 29.Spoth RL, Greenberg MT. Toward a comprehensive strategy for effective practitioner-scientist partnerships and larger-scale community benefits. Am J Community Psychol 2005;35:107–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spoth R, Greenberg MT, Bierman K, Redmond C. PROSPER community-university partnerships model for public education systems: capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. [Invited article for special issue]Prev Sci 2004;5:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spoth R, Guyll M, Lillehoj CJ, Redmond C, Greenberg M. PROSPER study of evidence-based intervention implementation quality by community-university partnerships. J Community Psychol 2007;35:981–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spoth R, Guyll M, Trudeau L, Goldberg-Lillehoj C. Two studies of proximal outcomes and implementation quality of universal preventive interventions in a community-university collaboration context. J Community Psychol 2002;30:499–518 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spoth R, Clair S, Greenberg M, Redmond C, Shin C. Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: Maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. J Fam Psychol 2007;21:137–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spoth R, Molgaard V. Project Family: a partnership integrating research with the practice of promoting family and youth competencies. Chibucos TR, Lerner R, eds Serving Children and Families Through Community-University Partnerships: Success Stories. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic; 1999:127–137 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spoth R, Reyes ML, Redmond C, Shin C. Assessing a public health approach to delay onset and progression of adolescent substance use: latent transition and loglinear analyses of longitudinal family preventive intervention outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:619–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacKinnon DP. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, eds Multivariate Applications in Substance Use Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000:141–160 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 3rd ed.Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998-2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthén B, Kaplan D, Hollis M. On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika 1987;52:431–462 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kreft I, De Leeuw J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wothke W. Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, eds Modeling Longitudinal and Multilevel Data: Practical Issues, Applied Approaches, and Specific Examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000:219–240 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA 2008;299:211–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolf SH, Johnson RE. The break-even point: when medical advances are less important than improving the fidelity with which they are delivered. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:545–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woolf SH. Potential health and economic consequences of misplaced priorities. JAMA 2007;297:523–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spoth R. Opportunities to meet challenges in rural prevention research: findings from an evolving community-university partnership model. J Rural Health 2007;23:42–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spoth RL, Clair S, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on methamphetamine use among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:876–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Reducing adolescents' aggressive and hostile behaviors: Randomized trial effects of a brief family intervention four years past baseline. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:1248–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams RJ, Nowatzki N. Validity of adolescent self-report of substance use. Subst Use Misuse 2005;40:299–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The Prevalence and Incidence of Delinquent Behavior: 1976-1980. Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Institute; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: dimensionality and validity over 24 months. J Stud Alcohol 1995;56:383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams CL, Perry CL, Dudovitz B, et al. A home-based prevention program for sixth-grade alcohol use: results from Project Northland. J Prim Prev 1995;16:125–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hagman BT, Clifford PR, Noel NE, Davis CM, Cramond AJ. The utility of collateral informants in substance use research involving college students. Addict Behav 2007;32:2317–2323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]