Abstract

Background

African children have some of the highest rates of bacterial meningitis in the world. Bacterial meningitis in Africa is associated with high case fatality and frequent neuropsychological sequelae. The objective of this study is to present a comprehensive review of data on bacterial meningitis sequelae in children from the African continent.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify studies from Africa focusing on children aged between 1 month to 15 years with laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis. We extracted data on neuropsychological sequelae (hearing loss, vision loss, cognitive delay, speech/language disorder, behavioural problems, motor delay/impairment, and seizures) and mortality, by pathogen.

Results

A total of 37 articles were included in the final analysis representing 21 African countries and 6,029 children with confirmed meningitis. In these studies, nearly one fifth of bacterial meningitis survivors experienced in-hospital sequelae (median = 18%, interquartile range (IQR) = 13% to 27%). About a quarter of children surviving pneumococcal meningitis and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) meningitis had neuropsychological sequelae by the time of hospital discharge, a risk higher than in meningococcal meningitis cases (median = 7%). The highest in-hospital case fatality ratios observed were for pneumococcal meningitis (median = 35%) and Hib meningitis (median = 25%) compared to meningococcal meningitis (median = 4%). The 10 post-discharge studies of children surviving bacterial meningitis were of varying quality. In these studies, 10% of children followed-up post discharge died (range = 0% to 18%) and a quarter of survivors had neuropsychological sequelae (range = 3% to 47%) during an average follow-up period of 3 to 60 months.

Conclusion

Bacterial meningitis in Africa is associated with high mortality and risk of neuropsychological sequelae. Pneumococcal and Hib meningitis kill approximately one third of affected children and cause clinically evident sequelae in a quarter of survivors prior to hospital discharge. The three leading causes of bacterial meningitis are vaccine preventable, and routine use of conjugate vaccines could provide substantial health and economic benefits through the prevention of childhood meningitis cases, deaths and disability.

Background

Bacterial meningitis is a serious, often disabling and potentially fatal infection resulting in 170,000 deaths worldwide each year [1]. Young children are particularly vulnerable to bacterial meningitis, and when exposed poor outcomes may occur due to the immaturity of their immune systems. Two thirds of meningitis deaths in low-income countries occur among children under 15 years of age [2]. The main bacterial pathogens causing meningitis beyond the neonatal period are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) [3-5]. Pneumococcal meningitis is associated with the highest case fatality ratios (CFRs) globally [6]. In Africa, pneumococcal meningitis CFRs attain 45% compared to 29% for Hib meningitis and 8% for meningococcal meningitis [3].

Serious, long-term neuropsychological sequelae further increase the population impact of paediatric meningitis. Sequelae comprise a range of findings with implications for child development and functioning and include such deficits as hearing loss, vision loss, cognitive delay, speech/language disorder, behavioural problems, motor delay/impairment, and seizures [7,8]. Meningitis sequelae can present a long-term, serious hardship for families with limited means to care for a disabled child, especially in resource-poor settings.

Africa experiences a disproportionately large burden of meningitis due to its young population, epidemics in the meningitis belt and high rates of endemic disease. The incidence and CFRs associated with paediatric Hib and pneumococcal meningitis were highest in Africa compared to all other regions in a recent global review [9]. In addition, Africa is the only region with cyclic epidemics of meningitis that affect persons of all ages, with attack rates ranging from 100 to 800 per 100,000 population [10]. Epidemics of meningitis are mostly associated with meningococcus, but there is some evidence that increases in pneumococcal meningitis cases occur in parallel during the hot and dry season [11-13].

A safe and effective Hib conjugate vaccine is available and routinely used in most African countries. Pneumococcal vaccines are gradually being introduced with support from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI), and meningococcal vaccines will soon become available. Together with mortality, morbidity due to in-hospital and long-term neuropsychological sequelae must be incorporated into estimates of the burden of meningitis to evaluate the potential benefit of preventive efforts such as conjugate vaccines.

The objective of this paper is to present a systematic review of the sequelae following acute bacterial meningitis in African children between the ages of 1 month and 15 years. Several earlier reviews have examined mortality associated with bacterial meningitis [3,9]. This review focuses on studies with primary data on neuropsychological sequelae due to bacterial meningitis.

Methods

Literature search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search for articles published between January 1980 and August 2008 containing information on bacterial meningitis among children from continental Africa. Professional librarians searched eight databases: PubMed/Medline, Global Health Database, Embase, Biological Abstracts, Pascal, Current Contents, the Cochrane Library, and African Index Medicus. Search terms were based on the key words 'meningitis' and at least one of the following: bacteria, bacteraemia, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, or Neisseria meningitidis (see Additional file 1 for full search strategy). We also screened the reference lists of two global reviews for articles with published or unpublished data [5,9]. Citations were uploaded into an EndNote XI library (EndNote, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and de-duplicated.

Citation screening

Two screeners reviewed each citation by preset inclusion and exclusion criteria; discrepancies were resolved through a weekly conference call. We only included articles with original sequelae data on at least 30 paediatric cases of laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis from 1 or more African countries. Laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis was defined as bacterial identification in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by culture, Gram stain, rapid antigen test (such as the Binax NOW test (Binax Inc., Scarborough, ME, USA)), latex agglutination or polymerase chain reaction, or bacterial isolation from blood culture accompanied by CSF abnormalities such as high white blood cell count, low glucose or high protein. We accepted the article definitions of CSF abnormalities, including CSF white blood cell count greater than 10 to 100 cells/mm3, protein greater than 0.3 to 2 g/l, and CSF glucose less than 0.2 g/l or CSF glucose: blood glucose ratio lower than 0.5. Articles had to present sequelae data separately for children or have a majority of their subjects between the ages of 1 month and 15 years. Articles in all languages were considered for inclusion.

Data extraction

Detailed information on neuropsychological sequelae was collected and entered into a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Sequelae included hearing loss, vision loss, cognitive delay (including mental retardation and learning disability), speech/language disorder, behavioural problems, motor delay/impairment (including gross motor and fine motor impairment, impaired activities of daily living, hypertonia, and paralysis), seizures, and other neurological sequelae. In-hospital sequelae and deaths were defined as events that occurred after the initiation of treatment and prior to discharge, exclusive of complications observed at the time of admission. Post-discharge sequelae and deaths were defined as events that occurred or persisted after discharge as detected upon follow-up tracing of patients. Unless there was specific mention of patient follow-up after discharge, we assumed that sequelae were assessed in hospital.

We examined articles for overlaps in study population and outcomes: when these occurred, one article in the overlapping group was excluded or the outcomes partially extracted to avoid double counting cases. We also evaluated the consistency of papers by verifying that the numbers presented in the results section added up to the total subjects and total meningitis cases. If there were major or numerous inconsistencies in a paper, it was excluded from the final analysis.

Data analysis

The final database was transferred into Stata 10.0 for analysis (Stata, College Station, TX, USA). Outcomes of interest included risk of sequelae among survivors (both in hospital and post discharge) and case fatality ratios (in hospital and post discharge). Sequelae and mortality were calculated separately for pneumococcal, Hib, and meningococcal meningitis, and then for all laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis. For in-hospital sequelae prevalence, the denominator included all children surviving until discharge and evaluated for sequelae; for post-discharge sequelae prevalence, the denominator included children surviving until the follow-up visit and evaluated for sequelae. Case fatality ratios were calculated only for articles with at least 25 cases of confirmed bacterial meningitis and sequelae risks were calculated only for articles that assessed at least 25 survivors of bacterial meningitis.

African countries were grouped into regions to match the Global Burden of Disease analysis [9]: eastern Africa meningitis belt, middle Africa meningitis belt, western Africa meningitis belt, eastern Africa, middle Africa, western Africa, northern Africa and southern Africa (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of countries by African region

| Region | Countries |

| Africa Eastern Meningitis Endemic | Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, Uganda |

| Africa Middle Meningitis Endemic | Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad |

| Africa Western Meningitis Endemic | The Gambia, Ghana, Senegal, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria |

| Africa Eastern | Mauritius, Seychelles, Comoros, Djibouti, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, Burundi, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia |

| Africa Middle | Congo, Gabon, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea |

| Africa Western | Cape Verde, Sao Tome and Principe, Liberia, Sierra Leone |

| Africa Northern | Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco |

| Africa Southern | Namibia, South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland |

African countries are grouped into eight regions, based on the groupings used in the Global Burden of Disease analysis [9].

Results

Literature search and citation screening

We initially identified 2,268 citations, of which 1,168 remained after de-duplication (Figure 1). All unique citations were double screened and 1,039 were excluded. Among these, 43 review articles were identified of which 20 were retrieved in full and checked for pertinent, unique citations; no new citations were found through this process. A total of 43 articles could not be retrieved prior to 1 October 2008 and were hence excluded.

Figure 1.

Citations found through literature search.

In all, 86 articles were moved forward to the data extraction phase. Of those articles, 42 were excluded because they did not present sequelae data separately for laboratory-confirmed and unconfirmed cases of bacterial meningitis. An additional 7 articles were excluded due to inconsistencies in the data presented in the results; thus, 37 articles remained in the final analysis.

Articles included in the review

The 37 included articles present data from 21 different African countries (Figure 2 and Table 2). A total of 10 studies were conducted during a meningitis epidemic. All regions contributed some data on in-hospital sequelae. The western Africa meningitis belt region had the most data, with 12 articles including 2,394 cases of confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM) with known outcomes, while southern Africa had the least, with 2 articles including 140 cases of CBM with known outcomes (Table 3). Post-discharge sequelae data were more limited, and originated from only seven countries in northern Africa or the meningitis belt. Only 1,131 children with any type of CBM were assessed for post-discharge sequelae.

Figure 2.

Number of articles included in review by country and region.

Table 2.

List of articles included in review

| Reference | First author | Year of publication | Country | Region | Total no. of CBM cases |

| [33] | Abid | 1999 | Morocco | Africa Northern | 141 |

| [34] | Abid | 1999 | Morocco | Africa Northern | 118 |

| [35] | Akpede | 1999 | Nigeria | Western Meningitis | 63 |

| [36] | Bijlmer | 1990 | Gambia | Western Meningitis | 77 |

| [37] | Bissagnene | 1996 | Cote d'Ivoire | Western Meningitis | 654 |

| [38] | Bernard-Bonnin | 1985 | Cameroon | Middle Meningitis | 174 |

| [39,40] | Camara | 2003 | Senegal | Western Meningitis | 511 |

| [14] | Friedland | 1992 | South Africa | Africa Southern | 79 |

| [16] | Girgis | 1991 | Egypt | Africa Northern | 160 |

| [41] | Girgis | 1989 | Egypt | Africa Northern | 429 |

| [17] | Girgis | 1998 | Egypt | Africa Northern | 697 |

| [22] | Goetghebuer | 2000 | The Gambia | Western Meningitis | 257 |

| [42] | Grobler | 1997 | South Africa | Africa Southern | 61 |

| [43] | Hailu | 2001 | Ethiopia | Eastern Meningitis | 32 |

| [44] | Koko | 2000 | Gabon | Africa Middle | 91 |

| [45] | Kristos | 1993 | Ethiopia | Eastern Meningitis | 124 |

| [46] | Lagunju | Nigeria | Western Meningitis | 29 | |

| [47] | Mackie | 1992 | Ghana | Western Meningitis | 69 |

| [48] | Mbonda | 1995 | Cameroon | Middle Meningitis | 67 |

| [49] | Melaku | 2003 | Ethiopia | Eastern Meningitis | 53 |

| [50] | Mhirsi | 1992 | Tunisia | Africa Northern | 98 |

| [51] | Molyneux | 1998 | Malawi | Africa Eastern | 149 |

| [52] | Molyneux | 2000 | Malawi | Africa Eastern | 52 |

| [53] | Moreau | 1986 | Cote d'Ivoire | Western Meningitis | 47 |

| [54] | Mwangi | 2002 | Kenya | Eastern Meningitis | 224 |

| [55] | Ogunlesi | 2005 | Nigeria | Western Meningitis | 124 |

| [56] | Pelkonen | 2008 | Angola | Africa Middle | 403 |

| [57,58] | Razafindralambo | 2004 | Madagascar | Africa Eastern | 83 |

| [59] | Redjah | 1998 | Algeria | Africa Northern | 57 |

| [60,61] | Salih | 1990 | Sudan | Eastern Meningitis | 43 |

| [62] | Salih | 1990 | Sudan | Eastern Meningitis | 108 |

| [63] | Sangare | 2005 | Burkina Faso | Western Meningitis | 53 |

| [64] | Mefo | 1999 | Cameroon | Middle Meningitis | 99 |

| [65] | Soltani | 2005 | Tunisia | Africa Northern | 20 |

| [66] | Tall | 1992 | Burkina Faso | Western Meningitis | 285 |

| [15] | Thabet | 2007 | Tunisia | Africa Northern | 73 |

| [67] | WHO | 1993 | Mali and Niger | Western Meningitis | 426 |

The 37 articles included in this review are listed in the above table. Articles with overlapping data have two references listed in the 'reference' column but were extracted as one article in the review database.

CBM = confirmed bacterial meningitis; WHO = World Health Organization.

Table 3.

Numbers of articles and cases reviewed by region

| Region | No. articles | Total no. confirmed BM cases with follow-up | Median no. confirmed BM cases with follow-up (min, max) | Total no. evaluated for in-hospital sequelae | Total no. evaluated for post-discharge sequelae |

| Eastern Meningitis | 6 | 584 | 81 (32, 224) | 431 | 80 |

| Middle Meningitis | 3 | 340 | 99 (67, 174) | 211 | 67 |

| Western Meningitis | 12 | 2,394 | 85 (23, 654) | 1,353 | 168 |

| Africa Eastern | 3 | 284 | 83 (52, 149) | 173 | 0 |

| Africa Middle | 2 | 494 | (91, 403) | 332 | 0 |

| Africa Northern | 9 | 1,793 | 118 (20, 697) | 457 | 816 |

| Africa Southern | 2 | 140 | (61, 79) | 104 | 0 |

| Total | 37 | 6,029 | 3,061 | 1,131 |

A total of 3,061 survivors were evaluated for in-hospital sequelae. Most of the in-hospital sequelae data comes from the western Africa meningitis belt region. Much less data is available on post-discharge sequelae (n = 1,131 cases) because survivors of bacterial meningitis were lost to follow-up or died after hospital discharge. Most of the post-discharge data comes from the northern Africa region.

BM = bacterial meningitis.

In-hospital sequelae and mortality

All causes of CBM

In all, 27 articles reported in-hospital mortality data for 25 or more children with CBM (4,245 total cases); 24 of these articles also had sequelae data for at least 25 child survivors (2,971 total cases) (Table 4). Most studies (23 of 37, or 62%) included pneumococcus, Hib, and/or meningococcus. Nine studies also included other bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella, enterobacteria, Staphylococcus, other streptococci, Escherichia coli or Klebsiella. One study included only tuberculosis (TB) meningitis cases.

Table 4.

In-hospital outcomes for all causes of confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM), by study

| Reference | Country | No. CBM cases with known outcomes | CFR | No. cases assessed for sequelae | HL (%) | VL (%) | CD (%) | BP (%) | MI (%) | SZ (%) | Any neuropsychological sequelae (%) | Bacterial pathogens studied |

| [43] | Ethiopia | 32 | 34% | Spn, Hib, Nm, Gram negative enterococci | ||||||||

| [45] | Ethiopia | 124 | 2% | 121 | 3% | 8% | Nm | |||||

| [54] | Kenya | 224 | 33% | 150 | 27% | Spn, Hib, non-typhi Salmonella, enterobacteria, Streptococcus group A or B and others | ||||||

| [62] | Sudan | 108 | 4% | 104 | 3% | 2% | 5% | Nm | ||||

| [60] | Sudan | 43 | 19% | 35 | 20% | 11%a | 26% | Spn, Hib, Nm and others | ||||

| [38] | Cameroon | 174 | 30% | 121 | 17% | Spn, Hib, Nm, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, enterobacteria | ||||||

| [64] | Cameroon | 99 | 9% | 90 | 1%a | 1% | 4% | Spn, Hib, Nm | ||||

| [63] | Burkina Faso | 53 | 75% | Salmonella | ||||||||

| [66] | Burkina Faso | 92 | 22% | 72 | 7% | 18% | Hib | |||||

| [37] | Cote d'Ivoire | 654 | 41% | 380 | 6% | 1% | 2% | 19% | Spn, Hib | |||

| [53] | Cote d'Ivoire | 47 | 4% | 45 | 7% | Spn, Hib, Nm | ||||||

| [47] | Ghana | 67 | 27% | 49 | 8% | 2% | 6%a | 12% | Spn, Hib, Nm | |||

| [67] | Mali and Niger | 426 | 37% | 269 | 14% | Spn, Hib, Nm and others | ||||||

| [55] | Nigeria | 124 | 27% | 91 | 18% | Spn, Hib, Nm and others | ||||||

| [40] | Senegal | 511 | 18% | 420 | 21% | Spn, Hib, Nm | ||||||

| [56] | Angola | 403 | 33% | 270 | 24% | Spn, Hib, Nm, others | ||||||

| [57] | Madagascar | 83 | 31% | 57 | 30% | Spn, Hib, Nm | ||||||

| [51] | Malawi | 149 | 34% | 92 | 20% | Spn, Hib, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Group B Streptococcus, others | ||||||

| [52] | Malawi | 52 | 54% | Salmonella | ||||||||

| [44] | Gabon | 91 | 31% | 62 | 18% | Spn, Hib, Nm, Salmonella | ||||||

| [59] | Algeria | 57 | 4% | 55 | 2% | 2% | 4% | Hib | ||||

| [16] | Egypt | 160 | 51% | 78 | 8% | 6% | 18% | Tuberculosis | ||||

| [34] | Morocco | 118 | 1% | 117 | 9% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 21% | Nm | |

| [33] | Morocco | 141 | 9% | 128 | 27% | Spn | ||||||

| [15] | Tunisia | 73 | 14% | 61 | 7% | 2% | 5% | 3% | 34% | Spn | ||

| [42] | South Africa | 61 | 20% | 49 | 33% | 8% | 37% | 57% | Spn, Hib, Nm, others | |||

| [14] | South Africa | 79 | 30% | 55 | 5% | 38% | Spn |

This table presents data extracted on in-hospital sequelae among studies with at least 25 CBM survivors and case fatality ratios (CFRs) among studies with at least 25 CBM cases for all bacterial causes combined. The proportion of meningitis survivors with any kind of neuropsychological sequelae, either one or more deficits, ranged from 4% to 57%. The in-hospital CFR ranged from 1% to 75%. In many studies, the proportion of children affected by specific types of sequelae was not given. Most sequelae were diagnosed by clinical exam only during the course of hospitalisation.

aParalysis.

BP = behavioural problem; CD = cognitive delay; Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b; HL = hearing loss; MI = motor impairment; Nm = Neisseria meningitidis; Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae; SZ = seizures; VL = vision loss;

Cases were recruited and assessed for sequelae prospectively in 12 of 24 studies and retrospectively in 11 studies. One study recruited cases retrospectively and assessed outcomes prospectively. In 20 studies, sequelae were diagnosed by clinical exam only.

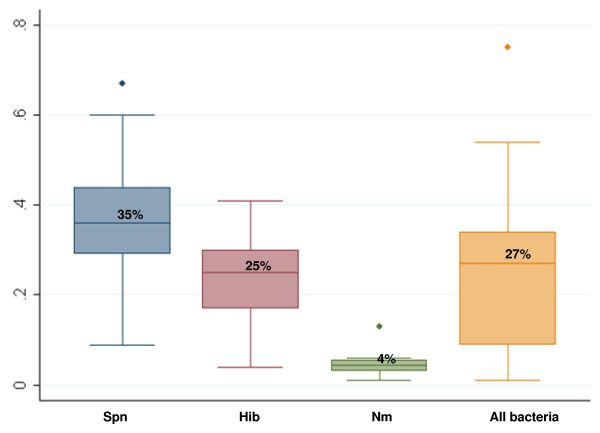

The risk of in-hospital neuropsychological sequelae (Figure 3) ranged from 4% to 57% for all causes of bacterial meningitis combined (median 18%, interquartile range (IQR) 13% to 27%). A total of 12 studies provided information by sequelae type. Hearing loss and motor impairments were most frequently reported, with estimates of risk ranging from 2% to 33% and 1% to 37%, respectively, based on 10 studies each. No studies had data on speech or language problems.

Figure 3.

Box plots of proportion of survivors with in-hospital sequelae. This figure presents box plots of the range of estimates for any in-hospital neuropsychological sequelae by pathogen and for all causes of confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM) combined. The upper border of the shaded box is the value of the 75th percentile and the lower border of the shaded box is the 25th percentile, and these two values define the interquartile range (IQR). The vertical 'whiskers' represent the values 1.5 IQRs above the 75th percentile and 1.5 IQRs below the 25th percentile. Any data points that are beyond the whiskers appear as outliers (dots). The median estimate for each group is represented by the horizontal line within the shaded box and the number above the horizontal line.

Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b, Nm = Neiserria meningitidis

CFRs for all confirmed types of bacterial meningitis ranged from 1% to 75%, (median 27%, IQR 9% to 34%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Box plots of in-hospital case fatality ratios.

Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b, Nm = Neiserria meningitidis

Pneumococcal meningitis

A total of 10 studies had data on pneumococcal meningitis sequelae, including 676 children. These studies found one or more sequelae in 16% to 38% of children (median 25%, IQR 21% to 32%) (Table 5). One study found hearing loss in 5% of cases [14], and another study examining hearing loss, vision loss, motor delay and seizures found that 2% to 7% of children had any one of these specific deficits [15]. A total of 14 articles including 1,463 children with pneumococcal meningitis provided information on CFR, which ranged from 9% to 67% (median 35%, IQR 29% to 44%).

Table 5.

In-hospital outcomes for the three main bacterial pathogens, by study

| Reference | Bacteria | Country | No. of CBM cases | In-hospital CFR | Total no. cases assessed for sequelae | HL (%) | VL (%) | CD (%) | BP (%) | MI (%) | SZ (%) | Any neuropsychological sequelae (%) |

| [38] | Spn | Cameroon | 74 | 39% | 45 | 16% | ||||||

| [37] | Spn | Cote d'Ivoire | 330 | 60% | 132 | 25% | ||||||

| [47] | Spn | Ghana | 33 | 36% | ||||||||

| [67] | Spn | Mali and Niger | 115 | 67% | 38 | 21% | ||||||

| [22] | Spn | The Gambia | 134 | 48% | ||||||||

| [57] | Spn | Madagascar | 40 | 40% | ||||||||

| [51] | Spn | Malawi | 62 | 44% | 32 | 25% | ||||||

| [44] | Spn | Gabon | 42 | 29% | 30 | 20% | ||||||

| [33] | Spn | Morocco | 141 | 9% | 128 | 27% | ||||||

| [15] | Spn | Tunisia | 73 | 14% | 61 | 7% | 2% | 5% | 3% | 34% | ||

| [41] | Spn | Egypt | 106 | 27% | ||||||||

| [14] | Spn | South Africa | 79 | 30% | 55 | 5% | 38% | |||||

| [54] | Spn | Kenya | 92 | 36% | 59 | 32% | ||||||

| [40] | Spn | Senegal | 142 | 32% | 96 | 28% | ||||||

| [54] | Hib | Kenya | 77 | 17% | 64 | 25% | ||||||

| [60] | Hib | Sudan | 25 | 16% | ||||||||

| [38] | Hib | Cameroon | 53 | 25% | 40 | 15% | ||||||

| [37] | Hib | Cote d'Ivoire | 314 | 21% | 248 | 6% | 1% | 2% | 17% | |||

| [36] | Hib | The Gambia | 77 | 25% | ||||||||

| [67] | Hib | Mali and Niger | 133 | 36% | 85 | 28% | ||||||

| [40] | Hib | Senegal | 216 | 18% | 178 | 6% | 3% | 2% | 27% | |||

| [22] | Hib | The Gambia | 123 | 27% | ||||||||

| [66] | Hib | Burkina Faso | 92 | 22% | 72 | 7% | 18% | |||||

| [57] | Hib | Madagascar | 35 | 29% | 25 | 44% | ||||||

| [51] | Hib | Malawi | 44 | 41% | ||||||||

| [44] | Hib | Gabon | 36 | 31% | ||||||||

| [59] | Hib | Algeria | 57 | 4% | 55 | 2% | 2% | 4% | ||||

| [41] | Hib | Egypt | 56 | 30% | ||||||||

| [42] | Hib | South Africa | 35 | 11% | 31 | 26% | 32% | 32%a | ||||

| [45] | Nm | Ethiopia | 124 | 2% | 121 | 3% | 8% | |||||

| [62] | Nm | Sudan | 108 | 4% | 104 | 3% | 2% | 5% | ||||

| [64] | Nm | Cameroon | 77 | 5% | 73 | 1%b | 1% | 3% | ||||

| [67] | Nm | Mali and Niger | 161 | 13% | 140 | 5% | ||||||

| [40] | Nm | Senegal | 153 | 5% | 146 | 10% | ||||||

| [41] | Nm | Egypt | 267 | 6% | ||||||||

| [34] | Nm | Morocco | 118 | 1% | 117 | 9% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 21% | |

| [50] | Nm | Tunisia | 57 | 4% |

This table presents the in-hospital sequelae and case fatality ratio (CFR) data available for 25 or more children diagnosed or surviving meningitis caused by 1 of the 3 main bacterial causes. Sequelae prevalences ranged from 16% to 38% for Spn meningitis, 4% to 44% for Hib meningitis and 3% to 21% for Nm meningitis.

aEstimated 'Any neuropsychological sequelae' based on single sequelae type with largest proportion; bparalysis.

BP = behavioural problem; CBM, confirmed bacterial meningitis; CD = cognitive delay; Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b; HL = hearing loss; MI = motor impairment; Nm = Neisseria meningitidis; Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae; SZ = seizures; VL = vision loss.

Hib meningitis

Altogether, 9 studies had data on Hib meningitis sequelae, including a total of 798 children. In all, 4% to 44% of survivors had neuropsychological sequelae (median 25%, IQR 17% to 28%) (Table 5). The risk of sequelae ranged from 2% to 26% for hearing loss (four studies), 1% to 3% for vision loss (two studies), 2% to 32% for motor delay/impairment (two studies), and 2% for seizures and 2% for cognitive delay (one study each). Among 15 articles including 1,373 children with Hib meningitis, the CFR ranged from 4% to 41% (median 25%, IQR 17% to 36%).

Meningococcal meningitis

In all, 6 studies including a total of 701 children had data on meningococcal meningitis sequelae with prevalence estimates ranging from 3% to 21% (median 7%, IQR 5% to 10%) (Table 5). Studies found hearing loss in 3% to 9% of subjects (three studies), vision loss in 3% (one study), behavioural problems in 1% (one study), motor impairment in 1% to 2% (three studies), and seizures in 1% (two studies). Among 8 studies following 1,065 children, the CFR for meningococcal meningitis ranged from 1% to 13% (median 4%, IQR 3% to 6%).

Post-discharge sequelae and mortality

A total of 10 prospective studies evaluated children for neuropsychological sequelae after discharge with CBM (Table 6). The follow-up period ranged from 2 to 90 months after hospital discharge. Loss to follow-up of patients ranged from 0% to 49% in eight studies and could not be calculated in two studies. Post-discharge mortality was reported in five studies and ranged from 0% to 18% (median 10%). Sequelae were generally assessed by clinical exam alone. One or more sequelae were found in 3% to 47% of survivors (median 25%, IQR 13% to 33%). The two studies enrolling only children with TB meningitis had sequelae estimates (24% and 32%) similar to studies including other bacterial pathogens [16,17]. Details of sequelae and mortality following discharge with pneumococcal, Hib and meningococcal meningitis are shown in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 6.

Post-discharge (PD) outcomes for all causes of confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM), by study

| Reference | Country | No. cases discharged | PD CFR | Average follow-up time, months | Total no. assessed for sequelae | HL (%) | VL (%) | CD (%) | SLD (%) | BP (%) | MI (%) | SZ (%) | Any neuropsychological sequelae (%) | Bacterial pathogens studied |

| [50] | Tunisia | 85 | 60 | 82 | 13% | Spn, Hib, Nm | ||||||||

| [41] | Egypt | 367 | 0% | 3 | 367 | 2% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 3% | Spn, Hib, Nm | |||

| [35] | Nigeria | 47 | 0% | 47 | 15% | 23% | Spn, Hib, Nm, Klebsiella and others | |||||||

| [16] | Egypt | 78 | (2 to 24) | 78 | 10% | 10% | 24% | Tuberculosis | ||||||

| [17] | Egypt | 289 | 12 | 289 | 8% | 7% | 32% | Tuberculosis | ||||||

| [49] | Ethiopia | 53 | 34% | 34%a | Spn, Hib, Nm, others | |||||||||

| [36] | The Gambia | 58 | 16% | 8 | 48 | 13% | Hib | |||||||

| [48] | Cameroon | 14 | 67 | 13% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 3%b | 7% | 25% | Spn, Hib, Nm, others | ||

| [60] | Sudan | 34 | 10% | (3 to 48) | 27 | 22% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 11% | 33% | Spn, Hib, Nm and others | ||

| [22] | The Gambia | 160 | 18% | (11 to 90) | 73 | 33% | 11% | 22% | 27%c | 19% | 47% | Spn, Hib |

The outcomes of children treated for all causes of CBM are shown for studies with >25 subjects. The number of cases discharged was calculated based on the number of CBM cases included in the study minus the number of children reported who died in-hospital. Post-discharge case fatality ratio (CFR) was calculated as the number of deaths after discharge divided by the number of cases with known follow-up; the denominator does not include cases lost to follow-up. Sequelae prevalence in children followed-up ranged from 3% to 47%. Half of the studies also had information on post-discharge CFR, which ranged from 0% to 18% in the period 3 to 90 months after illness.

aEstimated 'Any neuropsychological sequelae' based on single sequelae type with largest proportion; bparalysis; cgross motor impairment.

BP = behavioural problem; CD = cognitive delay; Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b; HL = hearing loss; MI = motor impairment; Nm = Neisseria meningitidis; Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae; SLD = speech or language disorder; SZ = seizures; VL = vision loss.

Table 7.

Post-discharge outcomes for the three main bacterial pathogens, by study

| Reference | Bacteria | Country | No. cases discharged | PD CFR | Average follow-up time, months (or range) | Total no. assessed for sequelae | HL (%) | VL (%) | CD (%) | SLD (%) | BP (%) | MI (%) | SZ (%) | Any neuropsychological sequelae (%) |

| [41] | Spn | Egypt | 77 | 0% | 3 | 77 | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | |||

| [48] | Spn | Cameroon | 14 | 34 | 21% | 6% | 9% | 9% | 3% | 6%a | 9% | 41% | ||

| [22] | Spn | The Gambia | 70 | 23% | (11 to 90) | 31 | 48% | 23% | 32% | 48%b | 10% | 58% | ||

| [41] | Hib | Egypt | 39 | 0% | 3 | 39 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |||

| [36] | Hib | The Gambia | 58 | 16% | 8 | 48 | 13% | |||||||

| [22] | Hib | The Gambia | 90 | 14% | (11 to 90) | 42 | 21% | 2% | 14% | 12%b | 26% | 38% | ||

| [50] | Nm | Tunisia | 55 | 60 | 55 | 9% | ||||||||

| [41] | Nm | Egypt | 251 | 0% | 3 | 251 | 2% | 0% | 0% | 1%a | 3% |

This table shows the findings of studies with post-discharge follow-up of at least 25 children following confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM) caused by 1 of the 3 main bacterial pathogens. The number of cases discharged was calculated based on the number of CBM cases included in the study minus the number of children reported who died in hospital. Post-discharge case fatality ratio (CFR) was calculated as the number of deaths after discharge divided by the number of cases with known follow-up; the denominator does not include cases lost to follow-up.

aParalysis; bgross motor impairment.

BP = behavioural problem; CD = cognitive delay; Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b; HL = hearing loss; MI = motor impairment; Nm = Neisseria meningitidis; Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae; SLD = speech or language disorder; SZ = seizures; VL = vision loss.

Table 8.

Overview of sequelae and mortality by bacterial pathogen and for all-cause confirmed bacterial meningitis (CBM)

| Type of bacteria | No. of studies with in-hospital data | Total no. cases | In-hospital CFR: median (min, max) | % With any in-hospital sequelae: median (min, max) | No. of studies with post-discharge data | Total no. cases discharged | % Cases died after discharge: median (min, max) | % With any post-discharge sequelae: median (min, max) |

| Pneumococcus | 14 | 1,463 | 35% (9% to 67%) | 25% (16% to 38%) | 3 | 147 | 0%, 22.5%a | 5%, 41%, 58%a |

| Hib | 15 | 1,373 | 25% (4% to 41%) | 25% (4% to 44%) | 3 | 187 | 0%, 14%, 16%a | 0%, 13%, 38%a |

| Meningococcus | 8 | 1,065 | 4% (1% to 13%) | 7% (3% to 21%) | 2 | 306 | 0%a | 3%, 9%a |

| All bacteria | 27 | 4,245 | 27% (1% to 75%) | 18% (4% to 57%) | 10 | 1,118 | 0% (0% to 18%) | 25% (3% to 47%) |

aActual values.

CFR = case fatality ratio; Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Discussion

In this review, we obtained comprehensive, up to date information on the burden of sequelae associated with bacterial meningitis in African children. We included 37 articles with sequelae data from 1980 to 2008, while an earlier review based sequelae estimates only on 10 articles published between 1970 and 2000 [3]. We estimated that the median risk of in-hospital sequelae was 25% for pneumococcal meningitis, 25% for Hib meningitis and 7% for meningococcal meningitis, while the median risk of post-discharge sequelae was 25% for all pathogens combined. These estimates are slightly lower than those found in the earlier African literature review [3], but the higher risk of sequelae for pneumococcal and Hib meningitis compared to meningococcal meningitis is consistent across the two reviews. The median CFR estimates in our review were 35% and 25% for pneumococcal and Hib meningitis, respectively, and thus slightly lower than the findings from two previous reviews [3,9].

Few studies report on the nature of the neuropsychological deficit beyond vision loss, hearing loss, seizures and gross motor impairment. Our database included more detailed and subtle neuropsychological deficit categories in keeping with the World Health Organization (WHO) international classification of functioning, disability and health [7]. This highlighted gaps in knowledge for the population studied: particularly lacking are data on cognitive delay, speech/language problems and behavioural problems.

In the studies we included, children with meningitis were treated in hospital with antibiotics recommended by the WHO (third generation cephalosporins or ampicillin plus chloramphenicol), and in some cases steroids [18]. Our findings suggest that even with appropriate antibiotic treatment, up to half of all children affected by pneumococcal and Hib meningitis die or experience clinically evident sequelae prior to hospital discharge. Increasing resistance to penicillin and chloramphenicol among pneumococcal strains may contribute to worse outcomes in some cases where access to third generation cephalosporins is limited. In our review, 15 of the articles (41%) reported using third generation cephalosporins as a first-line antibiotic in at least some cases. There were no clear trends in in-hospital sequelae risk over time likely because of relatively little heterogeneity in first-line therapies during the time period studied. Updated WHO guidelines promote the use of ceftriaxone in epidemic and non-epidemic settings as the first-line therapy for bacterial meningitis in Africa [19].

Further, a small number of studies included in the review show an increased risk of death and a 25% risk of long-term disability subsequent to discharge in children hospitalised for bacterial meningitis. The median estimates for in-hospital and post-discharge sequelae in our review did not differ greatly even though some sequelae following bacterial meningitis are expected to resolve over time [20]. African children experience the highest incidence rates for pneumococcal and Hib meningitis globally [9]. The high incidence, case fatality and sequelae risk due to bacterial meningitis underscore the public health importance of this disease and its poor outcome among children in Africa.

The articles included in this review represent 21 of the 52 African countries. In all, 44% of children with in-hospital outcome data were from the western Africa meningitis belt region and 72% of those with post-discharge data were from the northern Africa region. There were no major regional differences for study estimates of in-hospital sequelae risk associated with each of the three main bacteria (Table 5). The post-discharge sequelae studies had very few subjects overall and represent only seven countries. Among the post-discharge studies, the two northern Africa studies found the lowest risk of sequelae associated with individual bacterial pathogens (Table 7).

Our strict case definition for confirmed bacterial meningitis led to the exclusion of 42 articles with data on neuropsychological sequelae (49% of 86 studies). This definition was selected to ensure that cases of viral meningitis, which are generally less severe, were excluded and to enable us to calculate pathogen-specific estimates for sequelae and mortality. However, this methodological choice limits the generalisibility of our findings, given the small number and regional provenance of the remaining studies.

Many African children have limited access to medical care. Our review includes only patients who were admitted to a hospital, of which 77% were tertiary referral or teaching hospitals, had diagnostic testing for bacterial meningitis and received appropriate antibiotic therapy. These children are likely to have improved outcomes compared to children treated in lower-level facilities, where antibiotics are not always available, and children who did not reach medical care. Thus, our review likely underestimates the overall burden of sequelae and mortality in African children with bacterial meningitis.

This review identified very few studies with data on post-discharge outcomes of bacterial meningitis among African children. High loss to follow-up in these studies may lead to biased results, while small sample sizes limit the precision of our findings. However, a post-discharge study of children with pneumococcal meningitis from Bangladesh found that 11% died and 49% had long-term sequelae detectable 12 to 24 months post infection [21]. This study had a low loss to follow-up rate of 11%, and the proportion of children affected was on par with a similar study from The Gambia [22]. A recent review of the global burden of meningitis sequelae was conducted and found the highest risk of long-term sequelae in Africa compared to all other regions (Karen Edmond, senior lecturer in infectious disease epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, personal communication). Limited access to health care and poor health indicators make many African children highly susceptible to adverse outcomes following bacterial meningitis.

Further, the social and economic burden of survivors with neuropsychological sequelae is little studied in Africa. Most studies included in this review diagnosed sequelae based on clinical exam alone and thus represent profound deficits that would severely affect a child's developmental potential. In the absence of follow-up specialty services for affected children, major sequelae can result in lifelong disability. This in turn affects the disabled child's entire family, as caregivers must choose between caring for the disabled child, providing for siblings and working outside the home to supplement the family's income [21]. In a South African study following children with TB meningitis and their families, 35% of previously-employed mothers had to stop working and one in five families experienced a financial loss as a result of the child's illness; half of the schoolgoing children failed at least one school grade [23]. The societal burden of hearing loss is best documented, and in several countries meningitis has been consistently found to be a common cause of profound hearing loss [24-26].

Our review provides no information on the effect of HIV on meningitis outcomes. HIV may shift the relative frequencies of bacterial pathogens causing meningitis and contribute to childhood malnutrition, which was associated with worse prognosis in our risk factor analysis. A study from Malawi found a higher rate of mortality and recurrent disease in HIV-infected children with bacterial meningitis [27]. Another study from South Africa found a higher rate of pneumococcal meningitis and poor outcomes in HIV-infected children [28]. More research is needed on the effects of the HIV pandemic on bacterial meningitis outcomes, particularly in the high HIV prevalence areas of middle, southern and eastern Africa.

The three main bacterial causes of postneonatal childhood meningitis are all vaccine preventable. Even with appropriate treatment, pneumococcal and Hib meningitis kill approximately one third of affected children and cause clinically evident sequelae in a quarter of survivors prior to hospital discharge. Hib conjugate vaccine use has nearly eliminated Hib meningitis in many African countries [29,30]. In Uganda, it was estimated that the vaccine prevents 1,000 cases of severe meningitis sequelae each year in the country's population of 5.3 million children under 5 years of age [29]. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) are effective against invasive pneumococcal disease in African children, including meningitis [31]. In light of the high incidence of pneumococcal disease and its poor outcomes, these vaccines could prevent substantial numbers of meningitis-associated disabilities and deaths. PCV introduction into GAVI-eligible countries is underway and subsequent health and economic benefits will be closely monitored. Finally, though mortality and sequelae risk following meningococcal meningitis are not as high as with pneumococcal or Hib meningitis, the absolute numbers of sequelae and deaths occurring during meningococcal meningitis epidemics are tremendous. The epidemic potential of meningococcal meningitis has focused much attention on the introduction of meningococcal polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines in countries of the African meningitis belt. In addition, the related clinical syndrome of meningococcal sepsis, a fulminant disease that has been associated with CFRs of up to 80%, could decrease with the expanded use of meningococcal vaccine [32].

Evaluations of the health impact and cost effectiveness of conjugate vaccines should incorporate the economic and social impact of meningitis morbidity and mortality on families, many of which have little financial reserve to care for a child with a long-term disability. This review mainly includes children treated at tertiary care facilities and therefore underestimates the sequelae and mortality risk associated with bacterial meningitis. Thus, the true cost of meningitis and the true benefit of bacterial conjugate vaccines are likely to be tremendous.

Conclusion

Bacterial meningitis is a serious infection that has high risk of sequelae as well as mortality in African children. Even with appropriate treatment, pneumococcal and Hib meningitis kill approximately one third of affected children and cause clinically evident sequelae in a quarter of survivors prior to hospital discharge. The three leading causes of bacterial meningitis in childhood are vaccine preventable, and the regular use of these conjugate vaccines would reduce the high burden of morbidity and mortality in both epidemic and endemic settings.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MR managed the review team, screened citations for inclusion or exclusion, reviewed the data analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript. AU screened citations, helped manage the review team, reviewed the data analysis and helped draft the manuscript. LS designed, managed and cleaned the database, conducted the data analysis and created the results tables. JM contributed to study design, oversaw database management and analysis and edited the manuscript. FW provided technical input to the process. OL conceived of the project and provided technical oversight to design and execute the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Literature search strategy. Keywords, search terms and dates of execution for literature search in each of the eight databases used.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Funding support for this review was made available from the GAVI Alliance and the Sabin Vaccine Institute. We would like to thank the librarians at Johns Hopkins, Claire Twose and Donna Hesson, for their help in conducting the literature searches, finding articles and providing input at many points throughout the process. We would also like to thank our abstractors Madeline Beal, Dana Burshell, Sujitha Kurup, Mireille Mpoudi-Ngole, Nitya Nair and Chichi Onyemaechi, our reference manager Amir Fayek and our Microsoft Access designer Lynn Meyers. Thanks also to Dr Hope Johnson for providing the literature databases of the Global Disease Burden and Global Serotypes projects, to Dr Maria Deloria Knoll for her constructive feedback on the manuscript, and to Drs Samir Saha and Naila Khan for sharing their expertise and publications. Finally, this review would not have been possible without the logistic support of Michelle Moncrieffe-Foreman and Benedicta Kim at PneumoADIP and Ana Carvalho and Dr Ciro de Quadros at the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

Contributor Information

Meenakshi Ramakrishnan, Email: meenaramakri@gmail.com.

Aaron J Ulland, Email: aaron.ulland@sabin.org.

Laura C Steinhardt, Email: lsteinha@jhsph.edu.

Jennifer C Moïsi, Email: jmoisi@jhsph.edu.

Fred Were, Email: fwere@hcc.or.ke.

Orin S Levine, Email: olevine@jhsph.edu.

References

- World Health Organization N. meningitidis meningitis http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/meningitis/en/

- World Health Organization The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization

- Peltola H. Burden of meningitis and other severe bacterial infections of children in Africa: implications for prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:64–75. doi: 10.1086/317534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger JD, Hightower AW, Facklam RR, Gaventa S, Broome CV. Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1986: report of a multistate surveillance study. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1316–1323. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HL, Knoll MD, Levine OS, Freimanis L, Reithinger R, Muenz L, O'Brien KL. Serotype distribution of invasive pneumococcal disease among children globally: results from the Pneumococcal Global Serotype Project. 2008.

- Baraff LJ, Lee SI, Schriger DL. Outcomes of bacterial meningitis in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1993;12:389–384. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199305000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

- Khan NZ, Muslima H, Parveen M, Bhattacharya M, Begum N, Chowdhury S, Jahan M, Darmstadt GL. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants in Bangladesh. Pediatrics. 2006;118:280–289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll MD, O'Brien KL, Henkle E, Lee E, Watt J, McCall N, Mangtani P, Wolfson L, Cherian T. Global literature review of Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae invasive disease among children less than five years of age 1980-2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Meningococcal meningitis http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs141/en/

- Antonio M, Hakeem I, Awine T, Secka O, Sankareh K, Nsekpong D, Lahai G, Akisanya A, Egere U, Enwere G, Zaman SM, Hill PC, Corrah T, Cutts F, Greenwood BM, Adegbola RA. Seasonality and outbreak of a predominant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 clone from The Gambia: expansion of ST217 hypervirulent clonal complex in West Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaro S, Lourd M, Traoré Y, Njanpop-Lafourcade BM, Sawadogo A, Sangare L, Hien A, Ouedraogo MS, Sanou O, Parent du Châtelet I, Koeck JL, Gessner BD. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of a highly lethal pneumococcal meningitis epidemic in Burkina Faso. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:693–700. doi: 10.1086/506940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimkugel J, Adams FA, Gagneux S, Pfluger V, Flierl C, Awine E, Naegeli M, Dangy JP, Smith T, Hodgson A, Pluschke G. An outbreak of serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis in northern Ghana with features that are characteristic of Neisseria meningitidis meningitis epidemics. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:192–199. doi: 10.1086/431151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland IR, Klugman KP. Failure of chloramphenicol therapy in penicillin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Lancet. 1992;339:405–408. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90087-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet F, Tilouche S, Tabarki B, Amri F, Guediche MN, Sfar MT, Harbi A, Yacoub M, Essoussi AS. Pneumococcal meningitis mortality in children. Prognostic factors in a series of 73 cases. Arch de Pediatrie. 2007;14:334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis NI, Farid Z, Kilpatrick ME, Sultan Y, Mikhail IA. Dexamethasone adjunctive treatment for tuberculous meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:179–183. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis NI, Sultan Y, Farid Z, Mansour MM, Erian MW, Hanna LS, Mateczun AJ. Tuberculosis meningitis, Abbassia Fever Hospital-Naval Medical Research Unit No. 3-Cairo, Egypt, from 1976 to 1996. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:28–34. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Epidemic and pandemic alert and response. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. Standardized treatment of bacterial meningitis in Africa in epidemic and non epidemic situations. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy SL, Holmes SJ, Dodge PR, Feigin RD. Seizures and other neurological sequelae of bacterial meningitis in children. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1651–1657. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012133232402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha SK, Khan NZ, Ahmed NU, Ruhul Amin M, Hanif M, Mahbub M, Anwar KS, Qazi SA, Kilgore P, Baqui AH. Neurodevelopmental sequelae in pneumococcal meningitis cases in Bangladesh: a comprehensive follow-up study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:S90–S96. doi: 10.1086/596545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebuer T, West TE, Wermenbol V, Cadbury AL, Milligan P, Lloyd-Evans N, Adegbola RA, Mulholland EK, Greenwood BM, Weber MW. Outcome of meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b in children in The Gambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:207–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss-Mars AH, Lachman PI. Social factors associated with tuberculous meningitis. A study of children and their families in the western Cape. S Afr Med J. 1992;81:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiako MN. Profound childhood deafness in Nigeria: a three year survey. Ear Hearing. 1987;8:74–77. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198704000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abebe M. Sensorineural hearing loss in children with epidemic meningococcal meningitis at Tikur Anbessa Hospital. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41:113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson A, Smith T, Gagneux S, Akumah I, Adjuik M, Pluschke G, Binka F, Gento B. Survival and sequelae of meningococcal meningitis in Ghana. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1440–1446. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux EM, Tembo M, Kayira K, Bwanaisa L, Mweneychanya J, Njobvu A, Forsyth H, Rogerson S, Walsh AL, Molyneux ME. The effect of HIV infection on paediatric bacterial meningitis in Blantyre, Malawi. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:1112–1118. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.12.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhi SA, Madhi A, Petersen K, Khoosal M, Klugman KP. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection on the epidemiology and outcome of bacterial meningitis in South African children. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5:119–125. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(01)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowgill KD, Ndiritu M, Nyiro J, Slack MPE, Chiphatsi S, Ismail A, Kamau T, Mwangi I, English M, Newton C, Feikin DR, Scott JAG. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine introduction into routine childhood immunization in Kenya. JAMA. 2006;296:671–678. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adegbola RA, Secka O, Lahai G, Lloyd-Evans N, Njie A, Usen S, Oluwalana C, Obaro S, Weber M, Corrah T, Mulholland K, McAdam K, Greenwood B, Milligan PJ. Elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease from The Gambia after the introduction of routine immunisation with a Hib conjugate vaccine: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366:144–150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klugman KP, Madhi SA, Huebner RE, Kohberger R, Mbelle N, Pierce N, Group VT. A trial of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with and those without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1341–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deuren M, Brandtzaeg P, Meer JWM Van Der. Update on mengococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:144–166. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.1.144-166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid A, Bouskraoui M, Zineddine A, Ailal F, Najib J, Benbachir M. Meningites purulentes a pneumocoque chez l'enfant: a propos de 167 cas (Pneumococcal meningitis in children: a review of 167 cases) La Semaine des hopitaux de Paris. 1999;75:1308–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Abid A, Bouskraoui M, Zineddine A, Sodki M, Najib J, Benbachir M. Les meningites a meningocoques chez l'enfant a Casablanca: a propos de 245 cas (Meningococcal meningitis in children in Casablanca, Morocco: a review of 245 cases) Annales de pediatrie Paris. 1999;46:714–722. [Google Scholar]

- Akpede GO, Akuhwa RT, Ogiji EO, Ambe JP. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in bacterial meningitis in the tropics: a reappraisal with focus on the significance and risk of seizures. An Trop Paediatr. 1999;19:151–159. doi: 10.1080/02724939992473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlmer HA, Van Alphen L, Greenwood BM. The epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in children under five years of age in The Gambia, West Africa. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1210–1215. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissagnene E, Anzouan JB, Kakou A, Andoh J, Edoh V, Timite M, Kouame J, Dosso M, Kadio A. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in children in Abidjan: epidemiology, prognosis and implications for vaccination. Medecine d'Afrique Noire. 1996;43:511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Bonnin AC, Ekoe T. Purulent meningitis in children in Yaounde: epidemiological and prognostic aspects. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1985;65:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara B, Faye PM, Diouf S, Gueye Diagne NR, Diagne I, Cisse MF, Ba M, Sow HD, Kuakuvi N. Meningite pediatrique a Haemophilus influenzae b a Dakar (Pediatric Haemophilus influenzae b meningitis in Dakar) Medecine et maladies infectieuses. 2007;37:753–757. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara B, Cisse MF, Faye PM, Ba M, Tall-Dia A, Diouf S, Diagne I, Gueye Diagne NR, Ba A, Cisse Gueye A, Sow D, Kuakuvi N. La meningite purulente en milieu hospitalier pediatrique a Dakar (Senegal) (Purulent meningitis in a pediatric hospital in Dakar (Senegal)) Medecine et maladies infectieuses. 2003;33:422–426. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(03)00221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis NI, Farid Z, Mikhail IA, Farrag I, Sultan Y, Kilpatrick ME. Dexamethasone treatment for bacterial meningitis in children and adults. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:848–851. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobler AC, Hay IT. Bacterial meningitis in children at Kalafong Hospital, 1990-1995. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:1052–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailu M, Muhe L. Childhood meningitis in a tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa: clinical and epidemiological features. Ethiop Med J. 2001;39:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koko J, Batsielili S, Dufillot D, Kani F, Gahouma D, Moussavou A. Les meningites bacteriennes de l'enfant a Libreville, Gabon. Aspects epidemiologiques, therapeutiques et evolutifs (Bacterial meningitis in children in Libreville, Gabon. Epidemiological, therapeutic and prognostic features) Medecine et maladies infectieuses. 2000;30:50–56. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(00)88688-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre Kristos T, Muhe L. Epidemic meningococcal meningitis in children. A retrospective analysis of cases admitted to ESCH (1988) Ethiop Med J. 1993;31:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunja IA, Falade AG, Akinbami FO, Adegbola RA, Bakare RA. Childhood bacterial meningitis in Ibadan, Nigeria: antibiotic sensitivity pattern of pathogens, prognostic indices and outcome. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2008;37:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie EJ, Shears P, Frimpong E, Mustafa-Kutana SN. A study of bacterial meningitis in Kumasi, Ghana. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:143–148. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1992.11747559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonda E, Tietche P, Masso-Misse P, Ntaplia A, Mefo Sile H, Ouafo N, Tetanye E, Nkoulou H, Mbede J. Séquelles neurologiques des méningites bactériennes chez le nourrisson et l'enfant à Yaoundé. Medecine d'Afrique Noire. 1995;42:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Melaku A. Sensorineural hearing loss in children with epidemic meningococcal meningitis at Tikur Anbessa Hospital. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41:113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhirsi A, Boussoffara R, Ayadi A, Soua H, Driss N, Belkhir Y, Dalel H, Braham H, Pousse H, Essghairi K, Sfar MT. Prognosis of purulent meningitis of young child. Tunisie Medicale. 1992;70:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux E, Walsh A, Phiri A, Molyneux M. Acute bacterial meningitis in children admitted to the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi in 1996-97. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:610–618. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux EM, Walsh AL, Malenga G, Rogerson S, Molyneux ME. Salmonella meningitis in children in Blantyre, Malawi, 1996-1999. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2000;20:41–44. doi: 10.1080/02724930092057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau J, Calmel MB, Odehouri K. Activity of cefodizime (HR 221) in the treatment of purulent meningitis. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 1986;16:253–257. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(86)80086-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi I, Berkley J, Lowe B, Peshu N, Marsh K, Newton C. Acute bacterial meningitis in children admitted to a rural Kenyan hospital: increasing antibiotic resistance and outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:1042–1048. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlesi TA, Okeniyi JAO, Oyelami OA. Pyogenic meningitis in Ilesa, Nigeria. Indian Pediatrics. 2005;42:1019–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen T, Roine I, Monteiro L, Joao Simoes M, Anjos E, Pelerito A, Pitkaranta A, Bernardino L, Peltola H. Acute childhood bacterial meningitis in Luanda, Angola. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Razafindralambo M, Ravelomanana N, Randriamiharisoa FA, Migliani R, Clouzeau J, Raobijaona H, Rasamoelisoa J, Pfister P. Haemophilus influenzae, deuxieme cause des meningites bacteriennes de l'enfant a Madagascar (Haemophilus influenzae, the second cause of bacterial meningitis in children in Madagascar) Bulletin de la Societe de pathologie exotique. 2004;97:100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliani R, Clouzeau J, Decousser JW, Ravelomanana N, Rasamoelisoa J, Rabijaona H, Dromigny JA, Pfister P, Roux JF. Bacterial meningitis in children in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Arch Pediatrie. 2002;9:892–897. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(02)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redjah A, Mesbah S, Zmit FZ, Mohammedi D, Rahal K, Smati F, Dif A. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in infants. Clinical features and management in 57 cases. Annales Pediatrie. 1998;45:629–636. [Google Scholar]

- Salih MA, el Hag AI, Sid Ahmed H, Bushara M, Yasin I, Omer MI, Hofvander Y, Olcen P. Endemic bacterial meningitis in Sudanese children: aetiology, clinical findings, treatment and short-term outcome. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1990;10:203–210. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1990.11747431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih MA, Khaleefa OH, Bushara M, Taha ZB, Musa ZA, Kamil I, Hofvander Y, Olcen P. Long term sequelae of childhood acute bacterial meningitis in a developing country. A study from the Sudan. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:175–182. doi: 10.3109/00365549109023397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih MA, Ahmed HS, Osman KA, Kamil I, Palmgren H, Hofvander Y, Olcen P. Clinical features and complications of epidemic group A meningococcal disease in Sudanese children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1990;10:231–238. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1990.11747436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangare L, Kienou M, Lompo P, Ouedraogo-Traore R, Sanou I, Thiombiano R, Lompo M, Diabate A, Yameogo S, Sanogo I, Guira C. Salmonella meningitis in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, from 2000 to 2004. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 2007;100:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefo HS, Sile H, Mbonda E, Fezeu R, Fonkoua MC. Purulent meningitis in children in north Cameroon: epidemiological, diagnostic and prognostic aspects. Medecine d'Afrique Noire. 1999;46:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani MS, Bchir A, Amri F, Gueddiche N, Sfar T, Sahloul S, Garbouj M. Epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in Tunisia. East Med Health J. 2005;11:14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall FR, Elola A, Prazuck T, Traore A, Nacro B, Vincent Ballereau F. Meningites a Haemophilus influenzae a Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso) (Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in a hospital in Burkina-Faso) Medecine et maladies infectieuses. 1992;22:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(05)81433-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health organization Long-acting chloramphenicol for bacterial meningitis. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:117–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Literature search strategy. Keywords, search terms and dates of execution for literature search in each of the eight databases used.