Abstract

Efficacy trials indicate that an eating disorder prevention program involving dissonance-inducing activities that decrease thin-ideal internalization reduces risk for current and future eating pathology, yet it is unclear whether this program produces effects under real-world conditions. The present effectiveness trial tested whether this program produced effects when school staff recruit participants and deliver the intervention. Adolescent girls with body image concerns (N = 306; M age = 15.7 SD = 1.1) randomized to the dissonance intervention showed significantly greater decreases in thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting attempts, and eating disorder symptoms from pretest to posttest than those assigned to a psychoeducational brochure control condition, with the effects for body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms persisting through 1-year follow-up. Effects were slightly smaller than those observed in a prior efficacy trial, suggesting that this program is effective under real-world conditions, but that facilitator selection, training, and supervision could be improved.

Keywords: prevention, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders

Almost 10% of adolescent girls and young women experience threshold or subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder (Lewinsohn, Streigel-Moore, & Seeley, 2000; Stice, Marti, Shaw, & Jaconis, 2009). These eating disorders are marked by functional impairment, medical complications, and mental health service utilization, and increase risk for future obesity, depression, suicide, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and health problems (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, & Brook, 2002; Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Stice, Cameron, Killen, Hayward, & Taylor, 1999; Stice et al., 2009; Wilson, Becker, & Heffernan, 2003).

Although dozens of eating disorder prevention programs have been evaluated in randomized efficacy trials, a meta-analytic review (Stice, Shaw, & Marti, 2007b) found that only five have produced significant reductions in eating disorder symptoms relative to control participants that persisted through at least 6-month follow-up (McVey, Tweed, & Blackmore, 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, Butler, & Palti, 1995; Stewart, Carter, Drinkwater, Hainsworth, & Fairburn, 2001; Stice, Shaw, Burton, & Wade, 2006). Further, only the two programs evaluated in the last trial have been found to significantly reduce risk for future onset of eating disorders (Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008). The first is a dissonance intervention in which adolescent girls with body image concerns who have internalized the thin-ideal voluntarily engage in verbal, written, and behavioral exercises in which they critique this ideal (e.g., write essays and engage in role-plays that are counter-attitudinal). These activities theoretically produce psychological discomfort that motivates them to reduce pursuit of the thin-ideal, which decreases body dissatisfaction, dieting attempts, negative affect, and eating disorder symptoms. The second is a healthy weight intervention that promotes lasting healthy improvements to dietary intake and exercise as a way of improving body satisfaction among young women with body image concerns, which putatively decreases risk for unhealthy weight control behaviors that typify eating disorders. Participants implement a lifestyle change plan involving gradual healthy improvements to their diet and activity level. Adolescent girls assigned to these two interventions showed a 60–61% reduction in risk for onset of threshold or subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorders over 3-year follow-up relative to assessment-only controls (Stice, Marti et al., 2008).

In support of the intervention theory for the dissonance prevention program, this intervention produced significant reductions in thin-ideal internalization, change in thin-ideal internalization correlated with change in eating disorder symptoms and typically occurred before change in symptoms, and the intervention effects became significantly weaker when change in thin-ideal internalization was controlled statistically (Stice, Presnell, Gau, & Shaw, 2007a). Further, an experiment found that participants assigned to a high dissonance-induction version of this intervention reported lower eating disorder symptoms than those assigned to a low dissonance-induction version of the same intervention (Green, Scott, Diyankova, Gasser, & Pederson, 2005). Although the healthy weight intervention produced significant improvements in healthy eating and physical activity, change in these mediators did not consistently correlate with change in eating disorder symptoms and the intervention effects of symptoms did not consistently become weaker when change in the mediators was controlled statistically (Stice et al., 2007a), providing less support for the intervention theory for the healthy weight program.

Given that our group (e.g., Stice, Mazotti, Weibel, & Agras, 2000; Stice, Shaw et al., 2006) and others (e.g., Becker, Smith, & Ciao, 2005; Green et al., 2005; Matusek, Wendt, & Wiseman, 2004; Mitchell, Mazzeo, Rausch, & Cooke, 2007) have found that the dissonance program reduces eating disorder symptoms and given that the intervention theory for this intervention received support (Green et al., 2005; Stice et al., 2007a), we initiated a large effectiveness trial of this intervention. Whereas efficacy trials evaluate whether preventive interventions produce effects under carefully controlled experimental conditions, in which the facilitators are methodically trained and closely supervised, the intervention is typically delivered in adequately staffed research clinics, and the participants are often homogenous, effectiveness trials evaluate whether interventions produce effects when delivered by endogenous providers (e.g., school counselors, hospital staff) who are not closely supervised under real world conditions in natural settings with heterogeneous populations (Flay, 1986). It is vital to conduct effectiveness trials because a prevention program that produces effects in highly controlled efficacy trials may be ineffective when delivered under ecologically valid conditions (i.e., in the real world). In addition, effectiveness trials can provide information concerning the degree of training and supervision necessary to achieve the intervention effects. Effectiveness trials may also reveal problems that must be resolved before the prevention program can be successfully disseminated (e.g., effectiveness trials might indicate that screening procedures used in efficacy trials by research staff are not feasible in the real world because of limited school staffing).

There have been several eating disorder prevention trials with features consistent with effectiveness research. McVey and associates conducted two trials in which public health nurses facilitated the interventions under real world conditions in the schools, though research staff recruited participants. McVey, Lieberman, Voorberg, Wardrope, and Blackmore (2003a) found that participants who completed a 10-hour program that promoted critical media use, body acceptance, healthy weight control, and stress management skills showed greater decreases in eating disorder symptoms than assessment-only controls, yet, the effects did not replicate in the McVey, Lieberman, Voorberg, Wardrope, Blackmore, and Tweed, (2003b) trial. In another trial, teachers were responsible for delivery of a 1-year intervention under real-world conditions, though research staff recruited participants (McVey et al., 2007). This intervention produced significant reductions in eating disordered symptoms among female students that persisted through 6-month follow-up. Matusek, Wendt, and Wiseman (2004) evaluated abbreviated versions of the dissonance and healthy weight interventions developed by Stice and colleagues, with health educators who worked at the college delivering the interventions, but research staff recruiting participants. Female college students with body image concerns randomized to the dissonance and healthy weight intervention showed significantly greater reductions in eating disorder symptoms than assessment-only controls. Becker and associates evaluated an abbreviated version of the dissonance intervention and a media advocacy intervention when delivered by sorority member peer-leaders who had previously completed the programs and received 9 hours of additional training (Becker, Bull, Schaumberg, Cauble, & Franco, 2008; Becker, Smith, & Ciao, 2006). Sorority members randomized to the two interventions showed significant reductions in eating disorder symptoms at 8-month follow-up.

The present trial attempted to extend the results from these earlier trials by incorporating additional design elements that are consistent with effectiveness research (Roy-Byrne et al., 2003). First, we implemented this prevention program in three entire school districts rather than a subset of schools in a district. Second, high school nurses, counselors, and teachers, rather than research staff, recruited participants and delivered the dissonance intervention entirely within the school environment. Third, we simplified the facilitator training; endogenous providers completed a 4-hour training session and received minimal supervision to mimic real-world conditions. We also used a new 4-session version of the intervention (versus the original 3-session version) that made it easier for endogenous providers to cover the intervention material. Fourth, we used minimal exclusion criteria, which resulted in a heterogeneous sample; only adolescent females who met criteria for an eating disorder were excluded. Fifth, we used a minimal intervention psychoeducational brochure control condition because this was the only extant resource for students in local high schools, making this an ecologically valid control condition. We also improved upon the methodology of the typical prevention trial by using blinded diagnostic interviews to assess eating pathology and by conducting a 3-year follow-up.

We hypothesized that participants randomized to the dissonance intervention would show greater improvements in eating disorder risk factors (thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect), eating disorder symptoms, and risk for onset of threshold and subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, and escalation in body mass relative to participants in the psychoeducational brochure control condition. We focused on females between the ages of 14 and 18 because the peak period of risk for eating disorder onset occurs during this time (Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Stice et al., 2009) and because females are at much greater risk for eating disorders than males (Wilson et al., 2003). This report details the main effects of our interventions through 1-year follow-up.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 306 adolescent girls (M age = 15.7, SD = 1.1) with a mean body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) of 24.9 (SD = 6.1) recruited from a mid-sized city in the Northwest US. The sample was 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% African American, 9% Hispanic, 81% Caucasian, and 6% who specified other or mixed racial heritage, which was representative of the county (2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% African American, 82% Caucasian, 6% Hispanic). Parental education, a proxy for socioeconomic status, was 17% high school graduate or less, 24% some college, 38% college graduate, and 21% advanced graduate/professional degree, which was somewhat higher than the education of adults in the county (26% high school graduate or less; 36% some college; 16% college graduate; 10% graduate degree).

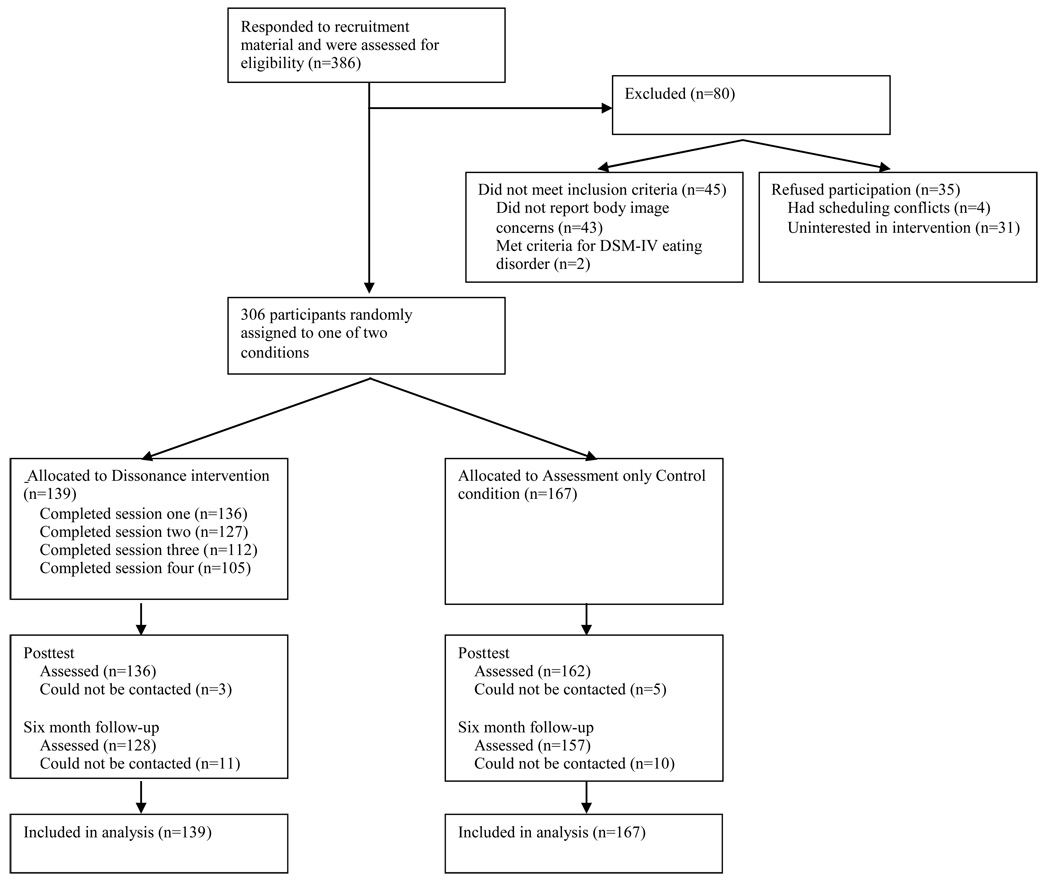

From April 2005 to November 2007, participants were recruited from high schools using direct mailings, flyers, and leaflets inviting females between the ages of 14 and 19 with body image concerns to participate in a study evaluating interventions designed to help females accept their bodies. In all, 386 students responded to the recruitment material (9.2% of the population), which is similar to recruitment efforts for other targeted prevention programs (e.g., 11.5% in Gilham et al., 2006). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants (and their parents if they were minors) before data were collected. Inclusion criteria were that participants (a) had to verbally affirm that they had body image concerns with a research assistant over the phone and (b) had to be between 14 and 19 years of age. We used a simple self-selection screening approach for this targeted prevention trial, rather than requiring a specific response on a body dissatisfaction screening measure administered school-wide, because we wanted to simplify recruitment to facilitate dissemination. The sole exclusion criterion was that participants could not meet criteria for DSM-IV anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder at pretest. The 2 individuals who met criteria for these disorders were strongly encouraged to seek treatment, provided with referrals, and told that these prevention programs were not appropriate for them. An additional 43 individuals were excluded because they did not affirm body image concerns, 31 declined to participate after learning more about the trial, and 4 had scheduling conflicts that prevented participation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Throughout the Study

In this 2-arm trial, participants were randomly assigned to the dissonance intervention or a psychoeducational brochure control condition via coin toss. The dissonance intervention consisted of 4 weekly 1-hour group sessions with 6–10 participants. The intervention was typically co-facilitated by two school nurses or counselors. A scripted treatment manual was used for dissonance intervention. Facilitator training involved (a) reading the manual to become familiar with the intervention, and (b) attending a 4-hour workshop to learn the conceptual rationale for the intervention and supporting evidence, discuss and role-play key elements from the sessions, and discuss process issues, including confidentiality, making referrals, and achieving good homework compliance and retention.

Participants provided interview and survey data at pretest, posttest (termination of the intervention), 6-month follow-up, and at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up. Female assessors, who had at least a bachelor degree in psychology, were blinded to the condition of participants. Assessors attended 24 hours of training, wherein they received instruction in interview skills, reviewed diagnostic criteria for relevant disorders, observed simulated interviews, and role-played interviews. They also attended annual training workshops. They had to demonstrate high inter-rater agreement (kappa [k] > .80) with supervisors using 12 tape-recorded interviews conducted with individuals with and without eating disorders before collecting data. Weekly consensus meetings were held to resolve ambiguous diagnostic issues (e.g., whether a particular eating episode should be coded as a binge episode). Participants were paid $15 for completing each assessment, which were usually conducted at schools. The local Institutional Review Board approved this project. No adverse events occurred.

Dissonance intervention

Several principles guided the development of the dissonance intervention. We minimized didactic presentation because psychoeducational interventions are less effective than those that actively engage participants (Stice et al., 2007b). We included exercises that require participants to apply the skills taught in the program to facilitate skill acquisition. We used homework to reinforce the skills taught in the sessions and help participants learn how to apply the skills. We used motivational enhancement exercises to maximize motivation to use the new skills (e.g., reviewed costs of body image concerns). We included activities to foster group cohesion. (96%; McVey et al., 2003a).

Session 1

Participants were informed that this intervention is based on the idea that discussing the costs of the thin-ideal perpetuated by our society can improve body satisfaction. They were asked if they would be willing to try this approach and verbal affirmation of their commitment was solicited. This initial session was interactive with participant-driven discussions of the definition and origins of the thin-ideal, how it is perpetuated, the impact of messages about the thin-ideal from family, peers, dating partners, and the media, and how corporations profit from this unrealistic standard. For homework, participants were asked to write a letter to a hypothetical younger girl that discussed the costs of pursuing of the thin-ideal and to examine their reflection in a full-length mirror, recording positive aspects of themselves.

Session 2

We reviewed points from the previous session and discussed participants’ reactions to writing the letter regarding the costs of pursuing the thin-ideal and the main costs each participant generated. Second, participants discussed the self-affirmation exercise and the feelings and thoughts she had during this exercise. They were asked to share what they like about themselves. Third, a counter-attitudinal role-play was conducted, wherein each participant attempted to dissuade the group leaders from pursuing the thin-ideal. For homework, participants were asked to provide three examples from their lives concerning pressures to be thin and generate verbal challenges to these pressures. They were also asked to produce a top-10 list of things girls/women can do to resist the thin-ideal.

Session 3

After an overview of the past session, participants discussed an example from their lives concerning pressure to be thin and how they might verbally challenge this pressure. Next, they generated “quick comebacks” that challenge thin-ideal statements made by peers. Participants then discussed the reasons they signed up for the class and identified their body image concerns. They were asked to challenge themselves with a behavioral experiment related to body image concerns in the next week (e.g., wearing shorts if they have avoided doing so because of body dissatisfaction). Next, they were asked to share items from their top-10 list of things girls/women can do to resist the thin-ideal. For a second homework assignment, they were asked to enact one of their body activism ideas.

Session 4

After reviewing the last session, each participant shared her experiences with and reaction to her behavioral challenge. They were encouraged to continue to challenge themselves and their body-related concerns in the future. Next, participants’ experiences with the body activism exercise were discussed. Then, more subtle ways in which the thin-ideal is perpetuated were discussed (e.g., joining in when friends complain about their bodies). Participants were given a list of these types of subtle statements and asked to identify how each perpetuates the thin-ideal. Difficulties participants might encounter in resisting the thin-ideal were next reviewed, as well as how each could be addressed. To further increase awareness, participants explored future pressures to conform to the thin-ideal and ways of responding to those pressures. Next, group members discussed how to talk about one’s body in a positive, rather than a negative, way. For homework, participants were asked to write a letter to another hypothetical younger girl about how to avoid developing body image concerns, and select a self-affirmation exercise to complete at home (e.g., when given a compliment, rather than objecting, “No, I’m so fat,” practice saying “Thank you”). They were asked to email the facilitator about their experiences with these exercises.

Supervision, fidelity ratings, and competence ratings

All sessions were audiotaped. The first author reviewed an average of 6 sessions for each facilitator and sent brief supervisory email messages that generally praised facilitators for good group management skills and adherence to the script, but sometimes offered constructive suggestions (e.g., try to encourage verbal participation from all group members). The second and fourth authors independently coded a randomly selected sample of 50% of the sessions for implementation fidelity and facilitator competence using scales adapted from prior trials (Stice, Rohde, Seeley, & Gau, 2008; Rohde et al., 2004). Ratings were reviewed and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Checklists assessing the major exercises and discussion topics for each session were developed (e.g., definition and origin of the thin-ideal, assign home exercise, behavioral experiment to challenge body image concerns, challenging fat talk). Each component was rated for degree of presentation (10-point scale from “No adherence; the section was skipped” to “Perfect; all material in the section was presented as written”). Facilitator competence was rated using 12 items that assess various indicators of a competent group facilitator (e.g., leaders express ideas clearly and at an appropriate pace, leaders attempt to allot equal speaking time for all members) using a 10-point scale. Four sessions were independently rated by three raters, resulting in high agreement for fidelity; ICC (3,1) = .92, and facilitator competence; ICC (3,1) = .96.

Psychoeducational Brochure Control Condition

Participants in this condition received a 2-page brochure produced by the National Eating Disorders Association in 2002. This psychoeducational brochure describes negative and positive body image, notes that negative body image is associated with increased risk for onset of eating disorders, and offers 10 steps for achieving a positive body image (e.g., keep a top 10 list of things you like about yourself, become a critical viewer of the mass media images of women). A psychoeducational brochure control condition seemed optimal for an effectiveness trial from an ecological validity standpoint because this is the most common intervention offered in schools (Mann et al., 1997). A fundamental question for an effectiveness trial is whether a new intervention works better than typical programming. Further, there is evidence that receiving psychoeducational brochure results in greater reductions in risk factors and eating disorder symptoms relative to assessment-only control conditions (Mutterperl & Sanderson, 2002; Sanderson & Du Vernay, 2008), suggesting that this minimal intervention may be of some benefit. Participants were referred to treatment if they met criteria for threshold or subthrehold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder at any assessment (as were participants in the dissonance condition).

Measures

Thin-ideal internalization

The Ideal-Body Stereotype Scale-Revised assessed thin-ideal internalization (Stice et al., 2006). Items used a response format ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (sample item: Slender women are more attractive). Items were averaged for this scale and those described below. This scale has shown internal consistency (α = .91), test-retest reliability (r = .80), predictive validity for bulimic symptom onset, and sensitivity to detecting intervention effects in samples of adolescent girls (Stice et al., 2006; α = .78 at T1).

Body dissatisfaction

Items from the Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Body Parts Scale (Berscheid, Walster, & Bohrnstedt, 1973) assessed dissatisfaction with nine body parts that are often of concern to females (e.g., stomach, thighs, hips) using a response scale ranging from 1 = extremely satisfied to 6 = extremely dissatisfied. This scale has shown internal consistency (α = .94), 3-week test-retest reliability (r = .90), predictive validity for bulimic symptom onset, and sensitivity to detecting intervention effects in samples of adolescent girls (Stice et al., 2006; α = .91 at T1).

Dieting

The Dutch Restrained Eating Scale (DRES; van Strien, Frijters, van Staveren, Defares, & Deurenberg, 1986) assesses the frequency of various dieting behaviors using a response scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. The DRES has shown internal consistency (α = .95), 2-week test-retest reliability (r = .82), convergent validity with self-reported caloric intake (but not objectively measured caloric intake), predictive validity for bulimic symptom onset, and sensitivity to detecting intervention effects in samples of adolescent girls and young women (Stice, Fisher, & Lowe, 2004; Stice et al., 2006; van Strien et al., 1986; α = .92 at T1).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depressive symptoms. For each item, participants select among four response options reflecting increasing levels of symptom severity (0 = never/less than 1 day in past week to 3 = most of the time/5–7 days in the past week). The CESD has shown internal consistency (α = .74 - .91), reliability (test-retest r = .57 - .59), and convergent validity with clinician ratings of depressive symptoms in adolescent samples (M r = .88; Andrews, Lewinsohn, Hops, & Roberts, 1993; Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991; α = .94 at T1).

Eating pathology

The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Interview, a semi-structured interview adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn et al., 1995), assessed DSM-IV eating disorder symptoms. Items assessing the symptoms in the past month were summed to form an overall eating disorder symptom composite for each assessment. A logarithmic base10 transformation was used to normalize this composite. We also tested whether the intervention reduced risk for onset of threshold or subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder among those free of these conditions at pretest following the definitions used previously (Stice et al., 2009; Stice, Marti et al., 2008). For a subthrehold anorexia nervosa diagnosis we required participants to have a BMI of between 90% and 85% of that expected for age and gender (vs. less than 85% of that expected for a threshold diagnosis), report a definite fear of weight gain, and report that weight and shape was definitely an aspect of self-evaluation. For subthreshold bulimia nervosa we required participants to report at least 6 uncontrollable binge eating episodes and 6 compensatory behavior episode over a 3-month period (an average of twice monthly for each, vs. twice weekly for a threshold diagnosis), and to report that weight and shape was definitely an aspect of self-evaluation. For subthreshold binge eating disorder we required that participants report at least 12 uncontrollable binge eating episodes/days over a 6-month period (vs. 48 for a threshold diagnosis), report fewer than 6 compensatory behavior episodes, report marked distress about binge eating, and report that binge eating was characterized by 3 or more of the following; rapid eating, eating until uncomfortably full, eating large amounts when not hungry, eating alone due to embarrassment, feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after overeating.

The symptom composite showed internal consistency (α = .92), 1-week test-retest reliability (r = .90), sensitivity to detecting intervention effects, and predictive validity for future onset of depression in past studies of adolescent girls and young women (Presnell & Stice, 2003; Stice, Burton, & Shaw, 2004; Stice et al., 2006). Threshold and subthreshold eating disorder diagnoses have shown 1-week test retest reliability (κ = .96) in a randomly selected subset of 137 participants from studies conducted in our lab and inter-rater agreement (κ = .86) in a randomly selected subset of 149 participants from studies of adolescent girls (Stice, Marti et al., 2008). In the current trial the symptom composite showed internal consistency (α = .84 at T1), inter-rater agreement (ICC r = .93) for 70 randomly selected participants, and test-retest reliability (ICC r = .95) for 72 randomly selected participants.

Body mass

The BMI was used to reflect adiposity (Pietrobelli et al., 1998). After removal of shoes and coats, height was measured to the nearest millimeter using stadiometers and weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg using digital scales. Two measures were obtained and averaged. BMI correlates with direct measures of body fat such as dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (r = .80 – .90) and health measures such as blood pressure, adverse lipoprotein profiles, and diabetes mellitus in samples of children and adolescents (Dietz & Robinson, 1998; Pietrobelli et al., 1998).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

With regard to attendance, a total of 67% of dissonance participants attended all 4 sessions, 18% attended 3 sessions, 5% attended 2 sessions, and 10% attended one session. Attendance was lower than in a trial of a universal prevention delivered as part of the middle-school curriculum (96%; McVey et al., 2003a) and a trial of a mandated universal prevention program offered to sorority members (90%; Becker et al., 2008); we could not locate other trials that reported attendance rates. The proportion of dissonance participants who completed at least 3 of the 6 homework sessions was 80%. Facilitators consistently adhered to the intervention manual and almost all provided the program in a competent manner. Implementation fidelity ratings (10-point scale) had a mean of 6.9 (range = 2–10; only 4% of the components had minimal adherence, which was defined as a score of 4 or less). Facilitator competence ratings (10-point scale) had a mean of 6.2 (range = 2–9; only 10% of items were rated “fair,” which was defined as a score of 4, or less). We could not locate eating disorder prevention trials that reported detailed information on homework completion, fidelity and competence for comparison purposes.

A subset of 85 participants answered questions about cross-condition contamination. Most did not remember the other condition (79%). Of the 18 (21%) who reported knowing the other condition, 11 gave an incorrect response (e.g., “They got the same thing as me,” “parents did a survey”). Of the 7 participants who correctly remembered the other condition, none reported talking with students in the other condition about activities they were asked to complete. Thus, there is little evidence of cross-condition contamination.

The 8% of participants who did not complete the assessments through 1-year follow-up did not differ from the 92% of participants retained in the trial on any demographic or outcome measures at pretest and attrition did not differ across conditions. Nonetheless, we used full information maximum likelihood (ML) estimation to impute missing data because this intent-to-treat approach produces more accurate and efficient parameter estimates than alternative imputation approaches such as last-observation-carried-forward (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Omnibus repeated measures ANOVA models tested whether there were differential changes in outcomes across the dissonance and control conditions from baseline to 1-year follow-up (condition was a 2-level between-subjects factor and time was a 4-level within-subject factor). Time x condition interactions indicated there was significantly differential change over time across conditions for thin ideal (F [3/912] = 7.65, p = <.001, r = .14), body dissatisfaction (F [3/912] = 7.83, p < .001, r = .11), dieting (F [3/912] = 4.27, p = .005, r = .07), and eating disorder symptoms (F [3/912] = 6.73, p < .001, r = .09). The time x condition interaction was not significant for depressive symptoms (F [3/912] = 1.41, p = .238, r = .06). Table 1 provides means and standard deviations across conditions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Pretest | Posttest (1 month) |

6-month Follow-up |

1-year Follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Thin ideal | ||||||||

| Dissonance | 3.35 | 0.59 | 2.93 | 0.68 | 3.15 | 0.63 | 3.13 | 0.57 |

| Control | 3.50 | 0.46 | 3.34 | 0.52 | 3.32 | 0.50 | 3.35 | 0.56 |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||||||

| Dissonance | 3.47 | 0.83 | 3.04 | 0.83 | 3.14 | 0.75 | 3.12 | 0.73 |

| Control | 3.16 | 0.78 | 3.08 | 0.74 | 3.00 | 0.73 | 3.00 | 0.71 |

| Dieting | ||||||||

| Dissonance | 2.35 | 0.86 | 1.82 | 0.80 | 1.96 | 0.77 | 1.94 | 0.77 |

| Control | 2.31 | 0.86 | 2.04 | 0.76 | 2.07 | 0.75 | 2.10 | 0.82 |

| 1Eating disorder symptoms | ||||||||

| Dissonance | 11.56 | 13.60 | 5.17 | 7.21 | 5.78 | 6.51 | 5.41 | 6.16 |

| Control | 8.94 | 10.34 | 6.12 | 7.14 | 6.54 | 10.10 | 6.09 | 7.57 |

Tabled means and standard deviations are non-transformed symptom counts

We next conducted focused follow-up repeated measures ANOVA models that contrasted the dissonance and control conditions at each follow-up to determine how long the significant differences persisted. In each model, condition was a 2-level between-subjects factor and time was a 2-level within-subjects factor (pretest to posttest, pretest to 6-month follow-up, and pretest to 1-year follow-up). The time x condition interactions test whether participants in one condition showed significantly greater decreases on the outcome than participants in the other condition at each particular follow-up. Time x condition interactions presented in Table 2 indicated that the dissonance intervention produced significantly greater decreases in thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms relative to assessment-only controls from pretest to posttest. Intervention effects for body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorder symptom effects persisted through 6-month and 1-year follow-up.

Table 2.

Significance Levels, and Effect Sizes (r) for the Focused Repeated Measures Time x Condition Interactions

| Pretest to Posttest Time × Condition Interaction |

Pretest to 6-Month Follow-up Time × Condition Interaction |

Pretest to 12-Month Follow-up Time × Condition Interaction |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | p-value | r | F-value | p-value | r | F-value | p-value | r | |

| Thin ideal | 17.46 | <.001 | .23 | 0.14 | .713 | .02 | 1.54 | .215 | .07 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 23.93 | <.001 | .27 | 4.77 | .030 | .12 | 5.39 | .021 | .13 |

| Dieting | 12.93 | <.001 | .20 | 3.43 | .065 | .11 | 6.15 | .014 | .14 |

| 1Eating disorder symptoms | 17.47 | <.001 | .23 | 6.14 | .014 | .14 | 8.72 | .003 | .17 |

Time by condition interactions and associated statistics are based on the log transformed symptom counts.

We next tested whether the intervention reduced risk for future onset of any threshold or subthreshold eating disorder among participants initially free of these conditions. By 1-year follow-up, eight participants in the psychoeducational brochure control condition (4.8%) and three participants in the dissonance condition (2.4%) showed onset of a threshold or subthreshold eating disorder. Although this difference corresponds to an odds ratio of 2.1, which reflects a 50% reduction in risk for onset of eating disorders, this difference did not reach significance according to Fisher’s Exact Test (χ2 [N = 291] = 1.19, p = .219).

To examine the clinical significance of the change in the eating disorder symptoms over the 1-year follow-up, we conducted reliable change score analysis using the reliable change index (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Rates of reliable change on the eating disorder symptom composite score did not significantly differ across conditions (p = .001, OR = 2.25, [95% CI = 1.38 – 3.67]), with 42% of the dissonance condition participants showed clinically significant change at the 1-year follow-up compared to 24% of the control participants.

Finally, repeated measures ANOVA models tested for differential change in BMI. Change in BMI did not differ significantly across the dissonance and control condition over the full 1-year follow-up period (F [3/912] = 1.71, p = .164, r = .01).

Discussion

Results of this effectiveness trial indicate that participants in the dissonance condition showed significantly greater decreases in eating disorder risk factors, including thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and dieting, and in eating disorder symptoms from pretest to posttest than assessment-only controls. The effects for body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms persisted through 1-year follow-up. The significant effects were small to medium in magnitude, suggesting that effects were clinically meaningful. Results also indicated that the reductions in eating disorder symptoms were clinically significant. The fact that pursuit of the thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction, chronic dietary efforts, and eating disordered behaviors are associated with emotional distress, functional impairment, and mental health treatment seeking (Newman et al., 1996; Wilson et al., 2003), implies that reductions in these outcomes should translate into an improved quality of life for intervention participants.

It was encouraging that this intervention produced many effects through 1-year follow-up in this effectiveness trial that were also observed in our large efficacy trial of this intervention (Stice et al., 2006), as well as previous independent evaluations of this prevention program (e.g., Becker et al., 2008; Matusek et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2007) because this suggests that the effects are reproducible. More centrally, the findings from the present trial suggest that positive intervention effects still emerge when real world providers deliver the prevention program in ecologically valid settings with a heterogeneous population. As such, the current results extend the evidence-base for this eating disorder prevention program. However, as shown in Table 3, the average intervention effects from the present effectiveness trial (M r = .17) were somewhat smaller than the average effects that emerged in the large efficacy trial (M r = .25), though it was encouraging that the effect for eating disorder symptoms at posttest was slightly larger in the present effectiveness trial, as this is arguably the most important outcome. The fact that the average the intervention effect from this effectiveness trial was 32% smaller than was the case in the earlier efficacy trial, as well as the fact that these effects could all be substantially larger, suggests that it would be prudent to improve facilitator training and supervision. Rather than lengthening training, which would increase the cost of intervention delivery, we think training could be improved by spending relatively more time role-playing delivery of the intervention and less time on the other training components. In addition, we think it might be advantageous to require that facilitators have experience conducting group-based interventions and have basic knowledge of body image and eating disturbances. It was not always the case that the facilitators that we identified at each school had this experience and expertise, which represents an important barrier to implementing prevention programs in this setting.

Table 3.

Comparison of Effect Sizes (r) from the Large Efficacy Trial (Stice et al., 2006) and the Present Effectiveness Trial

| Large Efficacy Trial | Present Effectiveness Trial | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest to Posttest |

Pretest to 6-Month Follow-up |

Pretest to 12-Month Follow-up |

Pretest to Posttest |

Pretest to 6-Month Follow-up |

Pretest to 12-Month Follow-up |

|||||||

| r | 95% CI | r | 95% CI | r | 95% CI | r | 95% CI | r | 95% CI | r | 95% CI | |

| Thin ideal | .38 | .28 – .48 | .20 | .11 – .29 | .37 | .28 – .46 | .24 | .16 – .33 | .02 | <.01 – .06 | .07 | .03 – .13 |

| Body dissatisfaction | .35 | .25 – .45 | .28 | .19 – .38 | .29 | .20 – .39 | .28 | .20 – .37 | .12 | .06 – .19 | .13 | .06 – .20 |

| Dieting | .27 | .18 – .37 | .17 | .09 – .26 | .20 | .12 – .29 | .20 | .13 – .29 | .10 | .05 – .17 | .14 | .08 – .22 |

| Eating disorder symptoms | .19 | .11 – .28 | .15 | .08 – .23 | .16 | .09 – .25 | .24 | .16 – .33 | .12 | .06 – .20 | .17 | .10 – .25 |

It is important to consider two factors when interpreting the somewhat smaller effect sizes from the present effectiveness trial. First, the facilitator from our large efficacy trial delivered the dissonance intervention 18 times, whereas the interventionists in the present effectiveness trial delivered the prevention program an average of only 2 times. Thus, the effectiveness trial may have produced somewhat smaller effects because the facilitators did not have sufficient time to develop expertise. This fundamental difference between the two types of trials may make it difficult to draw inferences regarding the reasons that effectiveness trials tend to produce smaller effects than efficacy trials. Second, the effects may have been somewhat smaller in the present effectiveness trial because we used a psychoeducational brochure control condition, versus the assessment-only control condition that was used in the large efficacy trial (Stice et al., 2006). There is evidence that adolescent girls and young women show reductions in eating disorder risk factors and eating disturbances in response to psychoeducational brochures (Mutterperl & Sanderson, 2002; Sanderson & De Vernay, 2008). In line with this interpretation, Table 1 suggests that participants in the control condition showed reductions in outcomes over time.

According to the intervention model, voluntarily critiquing the thin-ideal theoretically resulted in cognitive dissonance that motivates participants to reduce their subscription to this ideal, putatively resulting in a consequent reduction in body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. However, this theoretical explanation seems inconsistent with the fact that the effects for thin-ideal internalization did not persist as long as the effects for the other risk factors and for eating pathology. These results may imply that the other risk factors or non-specific factors play a more important role in mediating the effects of the intervention on eating disorder symptoms in this effectiveness trial. Alternatively, perhaps high school staff delivered the intervention differently than the graduate students in the prior efficacy trial (e.g., provided less of a chance for participants to critique the thin ideal), which attenuated effects for thin-ideal internalization. It is also possible that the effectiveness trial produced weaker effects because the high school facilitators were less similar in age to participants than was the case for the graduate students who served as facilitators in the efficacy trial.

It was noteworthy that in the present trial the dissonance intervention did not reduce negative affect, as has been observed in previous trials (e.g., Stice et al., 2000, 2003, 2006). Although this may suggest that it is difficult to achieve effects for this outcome under real-world conditions, the present trial assessed depressive symptoms, whereas the efficacy trials assessed general negative affect. Thus, this pattern of findings may simply imply that the dissonance intervention produces effects for negative affect rather then depressive symptoms.

Limitations

This trial improved upon many prior prevention trials by using random assignment, blinded diagnostic interviews, a large sample, and ratings of intervention fidelity and competence. However, it also had several limitations. We relied on self-report data, with the exception of the direct measures of height and weight, introducing the possibility that reporter bias might distorted our estimates of intervention effects. It might be wise to use biological measures of eating disorder symptoms, such as electrolyte screens. In addition, the sample was relatively homogeneous with regard to ethnicity and socioeconomic status, suggesting that care should be taken in generalizing the results to other populations. Given that African American and Hispanic adolescents report less thin-ideal internalization than Asian American and White adolescents (Shaw, Ramirez, Trost, Randall, & Stice, 2004), it may be useful to develop alternative prevention programs for the former two ethnic groups. Yet, the dissonance intervention has produced similar effects for Latino, Asian, and White participants (Rodriguez, Marchand, Ng, & Stice, 2008).

Implications for Prevention and Future Research

The present findings have several implications. First, it will be vital to determine ways to enhance the magnitude and duration of the intervention effects from this prevention program when offered in ecologically valid settings. We suspect that improved facilitator selection, training, and supervision could enhance intervention effects. Future studies should also investigate additional ways to enhance intervention effects, such as increasing the amount of effort required for the home exercises and videotaping sessions to increase perceived accountability for counter thin-ideal statements, both of which should enhance dissonance induction. Given the evidence that intervention effects do not persist as well when this prevention program is offered under ecological valid conditions, future studies should test whether adding booster sessions that involve additional dissonance-inducing activities, which are offered several months after the original 4-sessions, improve the persistence of intervention effects. Second, it would be useful to investigate procedures that are more effective in recruiting adolescents with body image concerns, because it is doubtful that we successfully recruited all students with body image concerns who could benefit from the program. It is our impression that adolescents who are introverted are reluctant to sign up for group-based interventions. It is also our perception that adolescents who are very overweight are reluctant to sign up for the intervention, potentially due to the belief that the intervention is not likely to resolve their body image concerns. Other adolescents may simply not sign up for any group-based interventions or research studies. It might be possible that offering students school credit for completing the body acceptance class or offering this intervention in smaller groups might improve recruitment. Third, it would be useful to conduct systematic dismantling studies that investigate which intervention components exert larger effects on outcomes and which exert relatively weaker effects. This information might allow the development of a more streamlined version of this intervention that is equally effective or permit the development of even more effective versions of this intervention. Finally, it will be important to initiate studies that investigate how best to disseminate this prevention program and implement it on a large-scale basis, which will be necessary to affect a reduction in the incidence of eating disorders in at-risk youth.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (MH70699) from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank project research assistants Cara Bohon, Krista Heim, Erica Marchand, and Janet Ng, our undergraduate volunteers, the Eugene, Springfield, and Bethel School Districts, the school staff who recruited participants and facilitated the groups, and the participants who made this study possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/ccp.

References

- Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. Psychometric properties of scales for the measurement of psychosocial variables associated with depression in adolescence. Psychological Reports. 1993;73:1019–1046. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.73.3.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Bull S, Schaumberg K, Cauble A, Franco A. Effectiveness of peer-led eating disorders prevention: A replication trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:347–354. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Smith LM, Ciao AC. Peer facilitated eating disorders prevention: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Smith L, Ciao AC. Reducing eating disorder risk factors in sorority members: A randomized trial. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G. The happy American body: A survey report. Psychology Today. 1973;7:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Use of body mass index (BMI) as a measure of overweight in children and adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;132:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Norman PA, Welch SL, O’Connor ME, Doll HA, Peveler RC. A prospective study of outcome in bulimia nervosa and the long-term effects of three psychological treatments. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:304–312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160054010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay B. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Preventive Medicine. 1986;15:451–474. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Freres DR, Lascher M, Litzinger S, Shatte A, Seligman MEP. School-based prevention of depression and anxiety symptoms in early adolescence: A pilot of a parent intervention component. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006;21 323-248. [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Scott N, Diyankova I, Gasser C, Pederson E. Eating disorder prevention: An experimental comparison of high level dissonance, low level dissonance, and no-treatment control. Eating Disorders. 2005;13:157–169. doi: 10.1080/10640260590918955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:545–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Huang K, Burgard D, Wright A, Hanson K. Are two interventions worse than none? Joint primary and secondary prevention of eating disorders in college females. Health Psychology. 1997;16:215–225. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusek JA, Wendt SJ, Wiseman CV. Dissonance thin-ideal and didactic healthy behavior eating disorder prevention programs: Results from a controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:376–388. doi: 10.1002/eat.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey GL, Lieberman M, Voorberg N, Wardrope D, Blackmore E. School-based peer support groups: A new approach to the prevention of disordered eating. Eating Disorders. 2003a;11:169–185. doi: 10.1080/10640260390218297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey GL, Lieberman M, Voorberg N, Wardrope D, Blackmore E, Tweed S. Replication of a peer support program designed to prevent disordered eating: Is life skills approach sufficient for all middle school students? Eating Disorders. 2003b;11:187–195. doi: 10.1080/10640260390218639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey G, Tweed S, Blackmore E. Healthy schools-healthy kids: A controlled evaluation of a comprehensive eating disorder prevention program. Body Image. 2007;4:115–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Rausch SM, Cooke KL. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: Evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:120–128. doi: 10.1002/eat.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutterperl JA, Sanderson CA. Mind over matter: Internalization of the thinness norm as a moderator of responsiveness to norm misperception education in college women. Health Psychology. 2002;21:519–523. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Butler R, Palti H. Eating disturbances among adolescent girls: Evaluation of a school-based primary prevention program. Journal of Nutritional Education. 1995;27:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton WR. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:552–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli A, Faith M, Allison D, Gallagher D, Chiumello G, Heymsfield S. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity among children and adolescents: A validation study. Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;132:204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general populaion. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: A comparison of depression scales. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R, Marchand E, Ng J, Stice E. Effects of a cognitive-dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program are similar for Asian American, Hispanic, and White participants. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:618–625. doi: 10.1002/eat.20532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Mace DE, Jorgensen JS, Seeley JR. An efficacy/effectiveness study of cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with comorbid major depression and conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:660–668. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121067.29744.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Sherbourne CD, Graske MG, Stein MB, Katon W, Sullivan G, et al. Moving treatment research from clinical trials to the real world. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:327–332. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell K, Stice E. An experimental test of the effect of weight-loss dieting on bulimic pathology: Tipping the scales in a different direction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CA, De Vernay M. Can a brochure-based intervention impact disordered eating? A preliminary examination of individual differences in responsiveness to a universal prevention approach. 2008 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw H, Ramirez L, Trost A, Randall P, Stice E. Body image and eating disturbances across ethnic groups: More similarities than differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:12–18. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DA, Carter JC, Drinkwater J, Hainsworth J, Fairburn CG. Modification of eating attitudes and behavior in adolescent girls: A controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:107–118. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200103)29:2<107::aid-eat1000>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton EM, Shaw H. Prospective relations between bulimic pathology, depression, and substance abuse: Unpacking comorbidity in adolescent girls. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:62–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Cameron R, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:967–974. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. Prevalence, incidence, duration, remission, diagnostic progression, and diagnostic crossover of threshold and subthreshold eating disorders in a community sample. 2009 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti N, Spoor S, Presnell K, Shaw H. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:329–340. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Mazotti L, Weibel D, Agras WS. Dissonance prevention program decreases thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms: A preliminary experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:206–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<206::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Gau J, Shaw H. Testing mediators of intervention effects in randomized controlled trials: An evaluation of two eating disorder prevention programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:20–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley J, Gau J. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents outperforms two alternative interventions: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Burton E, Wade E. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: Encouraging Findings. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:233–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien T, Frijters JE, Van Staveren WA, Defares PB, Deurenberg P. The predictive validity of the Dutch Restrained Eating Scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986;5:747–755. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Becker CB, Heffernan K. In: Child Psychopathology. 2nd ed. Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. New York Guilford: 2003. pp. 687–715. [Google Scholar]