Abstract

Prospective, longitudinal data from a community sample of 451 families were used to assess the unique contribution of paternal depressive symptoms to adolescent functioning. Results indicated that paternal depressive symptoms were significantly related to subsequent depressive symptoms in adolescent offspring; this association remained significant after controlling for previous adolescent depressive symptoms, maternal depressive symptoms, gender, and family demographic variables. Adolescent gender and perception of father-adolescent relationship closeness moderated this association such that paternal depressive symptoms were positively associated with adolescent depressive symptoms for girls whose relations with fathers lacked closeness. These findings add to a growing literature on the interpersonal mechanisms through which depression runs in families, highlighting the need for future investigation of paternal mental health, adolescent gender, and intrafamily relationship quality in relation to adolescent development.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, father-adolescent relations, adolescence, fathers, gender

Throughout their lives, children of depressed parents are at risk for a number of social and emotional adjustment difficulties (for review, see Goodman & Gotlib, 2002). Fathers have been dramatically underrepresented in this research (Phares, 1992), although recent findings indicate that paternal depression may be related to adolescent maladjustment (e.g., Connell & Goodman, 2002). Of the limited literature on paternal depression and adolescent development, few have controlled for the influence of maternal depression (see Kane & Garber, 2004), and most have been limited to cross-sectional design (Hammen, 2008). Using longitudinal data from a community sample, this project examines the unique contribution of paternal depressive symptoms to adolescent functioning and whether this process is moderated by adolescent gender and/or adolescent perception of father-adolescent relationship closeness.

Subdiagnostic depression during adolescence has a high recurrence rate and been linked to a wide range of psychopathology including major depression, anxiety disorders, and suicide (Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005). Two frequently studied risk factors are gender and parent-child relationship quality. During early adolescence, girls begin to experience significantly more depression than boys in both severity and frequency (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007). Girls’ increased risk has been attributed, in part, to the biological and psychosocial challenges they face during adolescence (Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1992). Adolescents’ negative evaluations of the parent-child relationship have also been associated with increased risk for depression, although these studies have typically been limited by cross-sectional data (e.g., Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007).

Research on child and adolescent adjustment has historically focused on attributes of the mother, limiting the understanding of fathers’ role in offspring psychopathology (Phares, 1992). However, a growing body of work has associated paternal depression with adolescent psychological problems, and findings indicate that the degree of offspring risk is comparable to that associated with maternal depression (for recent meta-analyses, see Connell & Goodman, 2002; Kane & Garber, 2004). Some data suggest that paternal mental health may moderate the well-documented association between maternal depression and child psychopathology (see Goodman & Gotlib, 2002). Other results indicate the need for future research to examine the effect of paternal depression on adolescent development after controlling for potential confounding effects of maternal depression (Kane & Garber, 2004).

The present study seeks to contribute to the literature by using prospective methods that allow us to investigate the extent to which paternal depressive symptoms predict adolescent functioning over and above other factors frequently associated with adolescent outcomes including previous adolescent depressive symptoms, maternal depressive symptoms, and family demographic variables. In addition, this study examines gender and adolescent perception of father-adolescent closeness as moderators of the longitudinal association between father and adolescent depressive symptoms. This investigation had three main goals, which are outlined here along with their corresponding hypotheses.

Assess the unique effect of paternal depressive symptoms on subsequent adolescent functioning. We predicted a positive association between paternal depressive symptoms and adolescent depressive symptoms, controlling for previous adolescent symptoms, maternal symptoms, family demographics, and adolescent gender (H1).

Examine adolescent gender and adolescent perception of father-adolescent closeness as moderators of the association between paternal depressive symptoms and adolescent functioning. We expected increased risk in females and adolescents experiencing low father-adolescent closeness (H2).

Examine whether the interaction between paternal depressive symptoms and father-adolescent closeness varies as a function of adolescent gender. We hypothesized that adolescent girls would be more depressed than boys at higher levels of paternal depressive symptoms when father-adolescent closeness was perceived as low (i.e., the three-way interaction of paternal depressive symptoms by closeness by gender; H3).

Method

Participants and Procedures

The sample includes 451 adolescents (236 female, 215 male) from two-parent intact families in rural Iowa. The study began in 1989 when the 7th grade adolescents averaged 13.2 years of age. Participants were from predominately middle- and lower-middle-class families who resided on farms (34%), in non-farm rural areas (12%), or in small towns (54%). Due to the ethnic composition of the area, families were European-Americans. Of the original 451 families, approximately 95% of the sample remained in the study at Year 2. No significant differences in parents’ age, family income, or mothers’ level of education were found between participants remaining in the study compared to those who dropped out. Fathers not in the analyses averaged 12.74 years of education compared to 13.57 for those who remained in the study, a statistically significant difference (p < .05).

Measures

Depressed mood

Adolescent and parent depressive symptoms were assessed using the self-reported 13-item SCL-90-R Depression Subscale (Derogatis, 1983). The SCL-90-R has demonstrated reliability and validity and has been used successfully in many studies of adults and adolescents (e.g., Essau, 2004). In our sample, internal consistencies for SCL-90-R depression were satisfactory at Year 1 (fathers α = .81; mothers α = .87; adolescents α = .79) and Year 2 (adolescents α = .89). Raw score means for fathers (M = .45, SD = .42) and mothers (M = .60, SD = .50) were somewhat higher than the mean for the normative non-patient sample (M = .36, SD = .44) reported by Derogatis (1983). Adolescent depressive symptoms at Year 1 for boys (M = .57, SD = .54) and girls (M = .67, SD = .63) were slightly lower than the reported mean for the adolescent normative sample (M = .80, SD = .69). These comparisons indicate that whereas rural adults may be slightly more depressed than urban adults, rural adolescents may experience less depressive symptoms than their counterparts in urban settings.

Adolescent depressive symptoms at Year 1 for girls were not statistically different from those of boys. At Year 2, girls’ symptoms (M = .56, SD = .48) were significantly higher than boys’ (M = .42, SD = .45); t (1) = 3.05 (p < .001). Over the course of this study, both genders experienced decreases in rates of depressive symptoms, but boys’ symptoms decreased more dramatically. Consistent with the finding that the peak age of onset for depression occurs during mid-adolescence (for review, see Rudolph, 2008), previous analyses using this data indicated that girls’ depressive symptoms sharply increased after the 8th grade, whereas boys’ symptom levels began to increase in 10th grade (Ge, Conger, & Elder Jr., 2001).

Relationship closeness

Adolescents reported on how close they felt to their father at Time 1 using Conger’s (1989) Father-Adolescent Closeness Scale, which consists of ten items assessing the father-adolescent relationship. Responses included 1 (never), 2 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), and 4 (often) on items such as: “how often does he show concern for your feelings and problems”, “how often does he keep his promises”, and “how often does he understand the way you feel about things”. Items were averaged and scored so a high score represented high closeness (α = 0.79).

Results

Ordinary least squares analyses were run to address the study objectives. In all analyses, previous adolescent depressive symptoms and maternal depressive symptoms were entered as covariates in order to establish temporal precedence and remove spurious sources of association between paternal and adolescent depressive symptoms. All continuous predictor variables were centered. Demographic measures including per capita family income, parental age, and parental education were included as statistical controls in all analyses due to their potential to influence adolescent depression (Lorant et al., 2003). These variables did not produce significant effects in any equation and, for the sake of brevity, were excluded from reported analyses.

Consistent with H1, paternal depressive symptoms were associated with increases in subsequent adolescent symptoms (β = .180; p < .01). This association remained significant after controlling for prior adolescent symptoms, maternal symptoms, and gender (see Table 1). Results also supported H2; compared to males, female offspring experienced more depressive symptoms as a function of paternal symptoms (b = −.243; p < .05), and the adverse effect of paternal symptoms on adolescent outcome increased dramatically as father-adolescent closeness decreased (β = −.189; p < .001).

Table 1.

Standardized Regression Coefficients Predicting Year 2 Adolescent Depressive Symptoms from Gender, Year 1 Paternal Depressive Symptoms, and Perceived Closeness with Father, Controlling for Year 1 Adolescent and Maternal Depressive Symptoms (n=421)

| Previous Adolescent Depressive Symptoms | .459*** |

| [.366] | |

| (.036) | |

| Maternal Depressive Symptoms | .118** |

| [.110] | |

| (.040) | |

| Gender (male = 1) | −.103* |

| [−.098] | |

| (.040) | |

| Paternal Depressive Symptoms | .180** |

| [.199] | |

| (.063) | |

| Perceived Closeness with Father | −.013 |

| [−.012] | |

| (.054) | |

| Paternal Depressive Symptoms by Gender | −.148* |

| [−.243] | |

| (.094) | |

| Perceived Closeness by Gender | −.015 |

| [−.020] | |

| .078 | |

| Paternal Depressive Symptoms by Closeness | −.189*** |

| [−.430] | |

| (.120) | |

| Paternal Depressive Symptoms by Gender by Closeness | .153** |

| [.592] | |

| (.207) | |

| Constant | .533 |

| R2 | .297*** |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are in brackets and standard errors are in parentheses.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

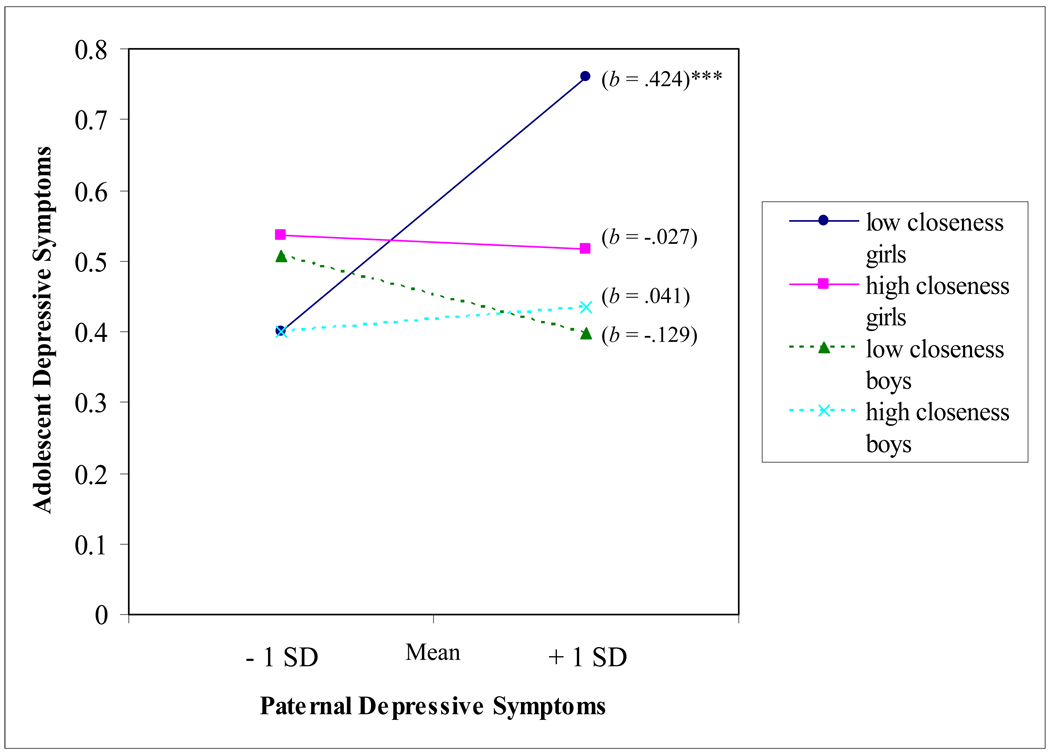

Controlling for all main effects and two-way interactions, the three-way interaction between paternal symptoms, father-adolescent closeness, and gender was statistically significant (β = .153; p < .01; H3). As suggested in Aiken and West (1991), post-hoc probing of this moderational effect was conducted in which simple regression equations were generated, one at each of the four combinations of gender and closeness at one standard deviation above and below the mean (see Figure 1). Only the slope for low closeness girls was significantly different from zero (b = .424; p < .001; the direction indicating that levels of adolescent girls’ depressive symptoms tended to be higher at higher levels of paternal depressive symptoms when father-daughter closeness was low). The independent variables in this model collectively explained 29.7% of the variance in adolescent functioning.

Figure 1.

Year 2 Adolescent Depressive Symptoms as Predicted by Year 1 Paternal Depressive Symptoms, Father-Adolescent Closeness, and Gender

Note. SD = standard deviation; b = unstandardized regression coefficient. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Discussion

These results suggest that adolescent gender and perception of the father-adolescent relationship play an important role in determining whether paternal depression is related to adolescent adjustment. Using prospective data from a community sample and controlling for maternal depressive symptoms, previous adolescent depressive symptoms, and family demographic variables, females reporting low father-adolescent closeness were particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of paternal depressive symptoms. Consistent with Kane and Garber (2004), our findings indicate a complex association between paternal mental health, the father-adolescent relationship, gender, and adolescent outcomes.

Previous research has often overlooked characteristics of the father (Phares, 1992), and surprisingly few studies have examined whether risk for psychopathology in offspring of depressed parents varies as a function of child gender (Goodman & Gotlib, 2002). In our data, paternal depressive symptoms were a strong predictor of adolescent functioning for girls whose relationships with fathers lacked closeness. Previous research has shown that compared to their male counterparts, adolescent females experience significantly more depression (Hankin et al., 2007) and tend to be more interpersonally oriented (for commentary, see Hops, 1995). Together, these characteristics may translate into increased vulnerability in relation to emotionally distant parenting from a depressed father. Findings from this study were also consistent with cross-sectional research suggesting that family environments characterized by the absence of close and supportive relations are associated with adolescent depressive symptoms (Sheeber et al., 2007).

There were several important limitations to this study that should be considered in future research. First, a substantial proportion of the variance in adolescent depressive symptoms remains unexplained by these independent variables and covariates. Future work should explore other explanatory variables including genetic and contextual processes by which paternal depression may influence adolescent functioning. Further studies are also needed to clarify the specific mechanisms underlying the effect of father-adolescent closeness in the present analyses. For example, in future research, fathers’ expression of affect and behaviors toward offspring (e.g., hostility, coercion, warmth, support) should be examined as moderators of the association between paternal depression and adolescent outcomes.

Second, the present research is limited by its sample characteristics. Replication of these findings with more diverse samples, including single-parent as well as urban and minority families, will increase our confidence in their external validity. Also, given the relatively low levels of symptoms reported from this rural community sample of adolescents, the results may not generalize to clinical populations. Finally, future work should extend this research by using multiple-informant and observational data. In spite of these limitations, this study adds to our understanding of the psychosocial processes by which depression runs in families and may have valuable applied implications. For example, in families with depressed fathers, therapeutic interventions aimed at improving relationships, particularly between fathers and daughters, may be especially helpful in preventing or alleviating adolescent depression.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health (HD047573, HD051746, and MH051361). Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/fam.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Father-Adolescent Closeness Scale. Created for Iowa Youth and Families Project. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R administration, scoring, and procedures Manual II. Townsend, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA. The association between family factors and depressive disorders in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger R, Elder G., Jr Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of depressed parents: Alternative pathways to risk for psychopathology. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL. Children of depressed parents. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H. Age- and gender-specific effects of parental depression: A commentary. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:428–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman MEP. Predictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:405–422. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Adolescent Depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 444–466. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and mothers: Associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:144–154. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]