Abstract

Up-regulation of Angiotensin type 1 receptors (AT1R) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) contributes to the sympatho-excitation in the chronic heart failure (CHF). However, the role of AT2R is not clear. In this study, we measured AT1R and AT2R protein expression in the RVLM and determined their effects on renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR) in anaesthetized sham and CHF rats. We found that: (1) while AT1R expression in the RVLM was up-regulated, the AT2R was significantly down-regulated (CHF: 0.06 ± 0.02 vs sham: 0.15 ± 0.02, P < 0.05); (2) simultaneously stimulating RVLM AT1R and AT2R by Ang II evoked sympatho-excitation, hypertension, and tachycardia in both sham and CHF rats, with greater responses in CHF; (3) stimulating RVLM AT1R with Ang II plus the specific AT2R antagonist PD123319 induced a larger sympatho-excitatory response than simultaneously stimulating AT1R and AT2R in sham rats, but not in CHF; (4) activating RVLM AT2R with CGP42112 induced a sympatho-inhibition, hypotension, and bradycardia only in sham rats (RSNA: 36.4 ± 5.1 % of baseline vs 102 ± 3.9 % of baseline in aCSF, P < 0.05); (5) pretreatment with ETYA, a general inhibitor of AA metabolism, into the RVLM attenuates the CGP42112 induced sympatho-inhibition. These results suggest that AT2R in the RVLM exhibits an inhibitory effect on sympathetic outflow, which is, at least partially, mediated by an AA metabolic pathway. These data implicate a down regulation in the AT2R as a contributory factor in the sympatho-excitation in CHF.

Keywords: Angiotensin II type 2 receptor, Angiotensin II type 1 receptor, rostral ventrolateral medulla, sympathetic outflow

Introduction

It is well accepted that chronic heart failure (CHF) is characterized by heightened sympathetic tone1. This excessive sympathetic outflow to the heart and peripheral vessels attempts to increase myocardial performance and increases peripheral resistance, thereby contributing to an increase in myocardial oxygen consumption leading to a further deterioration in cardiac function2. It has been well established that activation of Angiotensin II type 1 receptors (AT1R) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) evokes sympathetic excitation and pressor effects in normal animals3–5. Data from a previous study6 from our laboratory further suggested that the up-regulated AT1R expression in the RVLM and its enhanced intracellular signaling transduction plays a critical role in the sympatho-excitation in the CHF state. In addition, Ito et al.7 demonstrated that activation of AT1R in the RVLM appears to be important for the maintenance of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats, another animal model of sympatho-excitation.

In contrast with the AT1R, the functions of central Angiotensin II type 2 (AT2R) receptors regarding the regulation of autonomic system are not well understood. Although the AT2R predominates in the tissues during fetal development8, this receptor has been identified to exist in many adult mammalian tissues, including the brain9. Further experiments have demonstrated that central regions related to sympathetic function , such as the hypothalamus and brainstem, exhibit positive AT2R mRNA hybridization signals10, implying the involvement of AT2R in the regulation of sympathetic outflow. Kang et al.11 found that, in the cultured neurons from newborn rat hypothalamus and brainstem, stimulation of AT2R significantly increased neuronal voltage-gated potassium channel current (Ikv), and that the third intracellular loop of the AT2R is a key component for this effect12. This group further determined that the phospholipase A2 (PLA2) / arachidonic acid (AA) / 12-lipoxygenases (12-LO) pathway mediates the modulation of potassium currents by activation of the AT2R13. These data strongly suggest that the AT2R exhibits an inhibitory effect on neuronal function via increasing potassium current and therefore decreasing excitability of neurons. Indeed, a recent study by Matsuura et al.14 demonstrated an AT2R-mediated hyperpolarization and decrease in firing rate of RVLM presympathetic neurons, using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique in AT1R knockout mice. However, there are no reports concerning the effects of activating RVLM AT2R on sympathetic outflow and cardiovascular function in either normal or pathological conditions. In the current experiment, we measured both AT1R and AT2R protein expression in the RVLM from sham and CHF rats. We also observed the effects of stimulating RVLM AT2R and/or AT1R on renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), arterial blood pressure (ABP) and heart rate (HR) in the anaesthetized sham and CHF rats to determine the physiological and pathological significance of AT2R on autonomic regulation.

Methods

47 Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 290 to 380 g were used in these experiments. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Nebraska Medical Center and were carried out under the guidelines of the American Physiological Society and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Induction of rat CHF model

CHF was induced by coronary artery ligation as previously described15. Please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org for the detail in the online supplement.

Acute experiments

The acute experiment, including the general animal preparation, recording of RSNA, and RVLM microinjection procedures were carried out as previously described15. Please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org for the detail in the online supplement.

Preparation of RVLM and Western blot analysis

In a separate group of rats than those used for the above-mentioned microinjections, brains were removed and immediately frozen on dry ice, blocked in the coronal plane and sectioned at 100 µm thickness in a cryostat. The RVLM was punched using the technique of Palkovits and Brownstein16, and homogenized in RIPA buffer. Protein extraction from homogenates was used to analyze AT1R and AT2R expression by Western blot. The concentration of protein extracted was measured using a protein assay kit (Pierce; Rockford, IL) and adjusted to the same with equal volumes of 2× 4% SDS sample buffer. The samples were boiled for 5 min following by loading on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel (10 µg protein /30 µL per well) for electrophoresis using a Bio-Rad mini gel apparatus at 40 mA/ gel for 45 min. The fractionized protein on the gel was transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore) and electrophoresed at 300 mA for 90 min. The membrane was probed with primary antibodies (AT1R rabbit polyclonal antibody, Santa Cruz, 1:1000; AT2R rabbit polyclonal antibody, Santa Cruz, 1:1000) and secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, Santa Cruz, 1:2500), and then treated with enhanced chemi-luminescence substrate (Pierce; Rockford, IL) for 5 min at room temperature. The bands in the membrane were visualized and analyzed using UVP BioImaging Systems.

Statistical analyses

All data are described as the mean ± SEM. The integrated RSNA before agent intervention was set as a 100 % of baseline. The change in RSNA induced by a given agent was described as a % of baseline. A one way or two way ANOVA was used followed by either the Newman-Keuhls or Bonferroni post hoc analysis where appropriate. Statistical analysis was done with the aid of the Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS) software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline physiological parameters of sham and CHF rats

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of sham and CHF rats used in the present experiment. In the rats with CHF, gross examination revealed a dense scar in the anterior ventricular wall and the mean infarct area was 41.5 ± 3.6 % of the left ventricular area. No infarcts were found in sham-operated rats. Corresponding to this morphological alteration was a marked decrease in cardiac function of CHF rats. Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was significantly elevated and ejection fraction was significantly lowered in the CHF rats compared to sham rats. Moreover, many CHF rats, exhibited pulmonary edema, hydrothorax, and ascites. However, there were no significant differences in the arterial blood pressure and heart rate between sham and CHF rats.

Table 1.

Hemodyamic and Morphological Characteristics of Sham and CHF rats

| Measurements | Sham (n = 16) | CHF (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight, g | 392 ± 16 | 403 ± 20 |

| Heart Weight, g | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2* |

| Wet Lung Weight, g | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2* |

| Infarct Size, % of LV | 0 | 41.5 ± 3.6* |

| MAP, mmHg | 92.4 ± 3.9 | 89.7 ± 5.7 |

| Heart Rate, bpm | 354 ± 21 | 372 ± 19 |

| Ejection Fraction, % | 83 ± 5.9 | 46 ± 7.1* |

| LVEDP, mmHg | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 15.3 ± 2.1* |

Values are means ± SE. CHF, chronic heart failure; LV, left ventricle; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

P < 0.05 compared with sham.

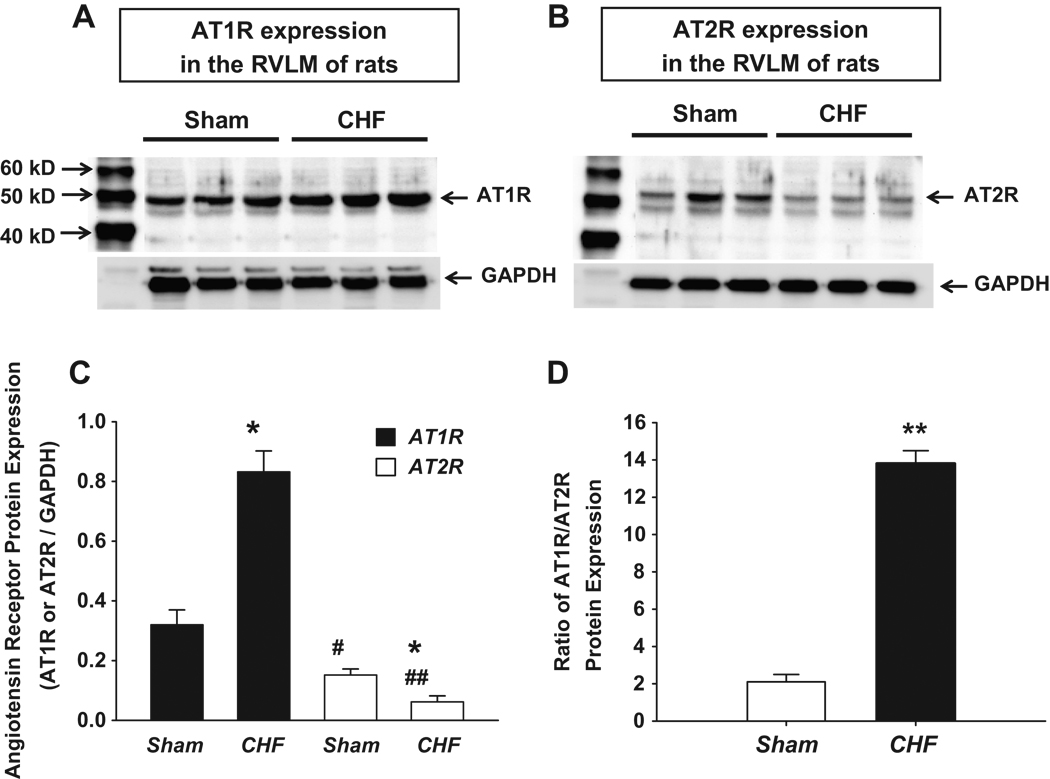

Expression of AT1R and AT2R in the RVLM of sham and CHF rats

Figure 1 shows the AT1R and AT2R protein expressions in the RVLM of sham and CHF rats. CHF rats exhibited higher AT1R expression than that in sham rats similar to results we found previously in CHF rabbits6. Interestingly, from the same RVLM tissue sample, we found a lower AT2R expression from CHF RVLM rats compared to sham rats. These data suggest that, in the CHF state, while AT1R expression in the RVLM was up-regulated, AT2R expression was significantly down-regulated. In normal conditions, the level of AT2R expression in the RVLM is only half of AT1R expression. In the CHF state, this disparity of AT1R and AT2R expression was increased due to the up regulated AT1R and the down regulated AT2R. Ang II activates both AT1R and AT2R. The ratio of these two Angiotensin receptors therefore determines the final effects of Ang II in a specific tissue or organ. From panel D in Figure 1, it can be seen that in CHF rats the ratio of AT1R to AT2R was markedly increased compared to that from sham rats (13.8 ± 0.7 vs 2.1 ± 0.4, respectively, p<0.01, panel 1D).

Figure 1.

Western blot showing AT1R and AT2R protein expression in the RVLM of sham and CHF rats. Panel A and B show representative Western blots. Panel C is the group data. Panel D is the ratio of AT1R to AT2R protein expression. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with sham. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 compared with the AT1R of the corresponding group in sham or CHF rats. n = 6 in each group.

Effects of stimulating RVLM AT1R and /or AT2R on RSNA and blood pressure in sham and CHF rats

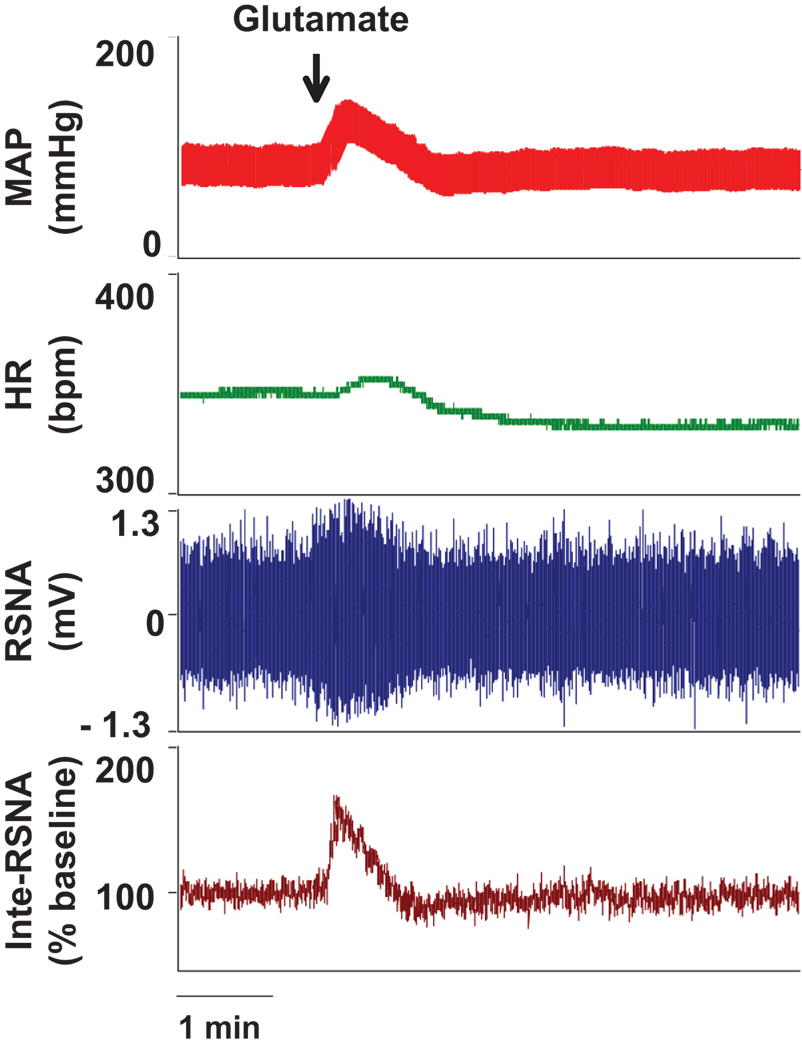

1. Functional location of RVLM by L-glutamate

Figure 2 shows the functional identification of the RVLM by microinjection of L-glutamate. A transient pressor, tachycardia, and sympatho-excitatory response was induced by microinjection of L-glutamate (5 nmol in 50 nL) unilaterally into the RVLM. This functional test was routinely carried out using one barrel of a three barreled micropipette before each reagent was given.

Figure 2.

Representative functional location of the RVLM by the elicitation of pressor, tachycardia, and sympathetic excitatory responses to microinjection of L-glutamate (5 nmol in 50 nL).

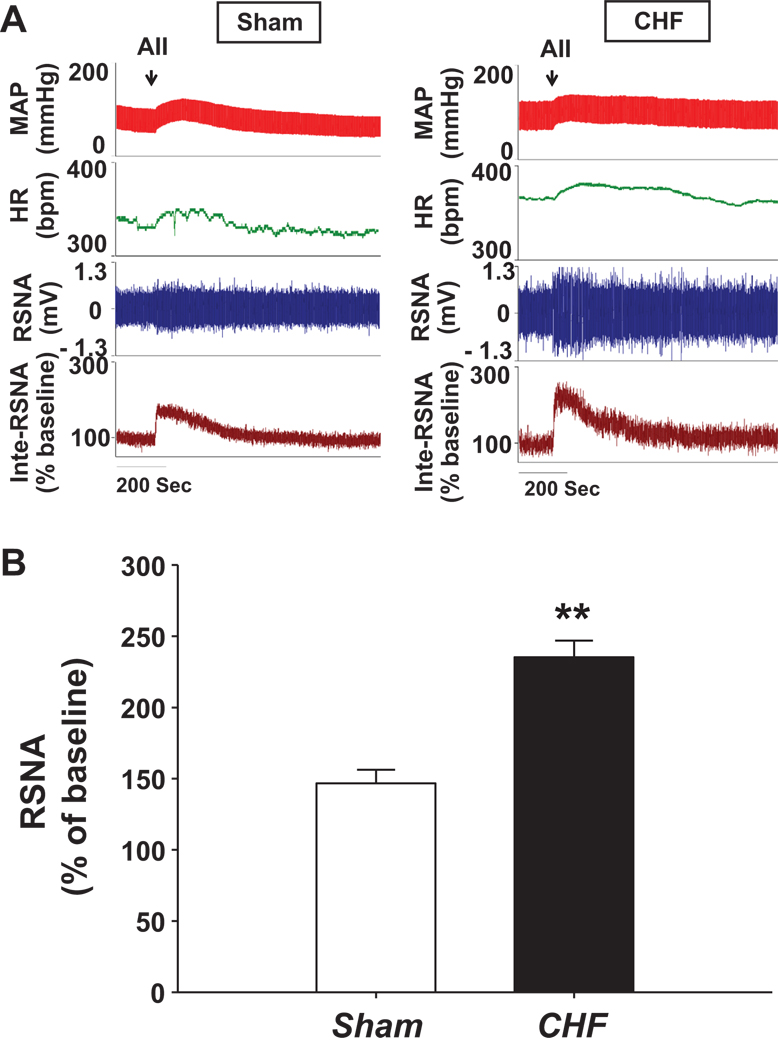

2. Simultaneously activating AT1R and AT2R by Ang II

Figure 3 shows the cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to microinjection of Ang II (50 pmol in 50 nL) unilaterally into the RVLM to stimulate AT1R and AT2R. Ang II induced sympatho-excitation in both sham (146.7 ± 9.4 % of baseline) and CHF (235.3 ± 11.6 % of baseline) rats, with a significantly larger response in the CHF rats (p<0.01). The enhanced sympathetic response to Ang II in the CHF state may be due to either up-regulation of AT1R expression, down-regulation of AT2R expression or both. The increase in MAP and HR were however similar between the two groups (ΔMAP = 24.7 ± 3.6 mmHg, ΔHR = 21.3 ± 6.4 bpm for sham and ΔMAP = 28.1 ± 2.3 mmHg, ΔHR = 26.9 ± 8.2 bpm for CHF rats).

Figure 3.

Effects of microinjecting Ang II into the RVLM on sympathetic outflow, heart rate and arterial pressure in sham and CHF rats. Panel A shows a representative trace and panel B is the group data showing the maximal change in RSNA. **P < 0.01 compared with the sham. n = 7 per group.

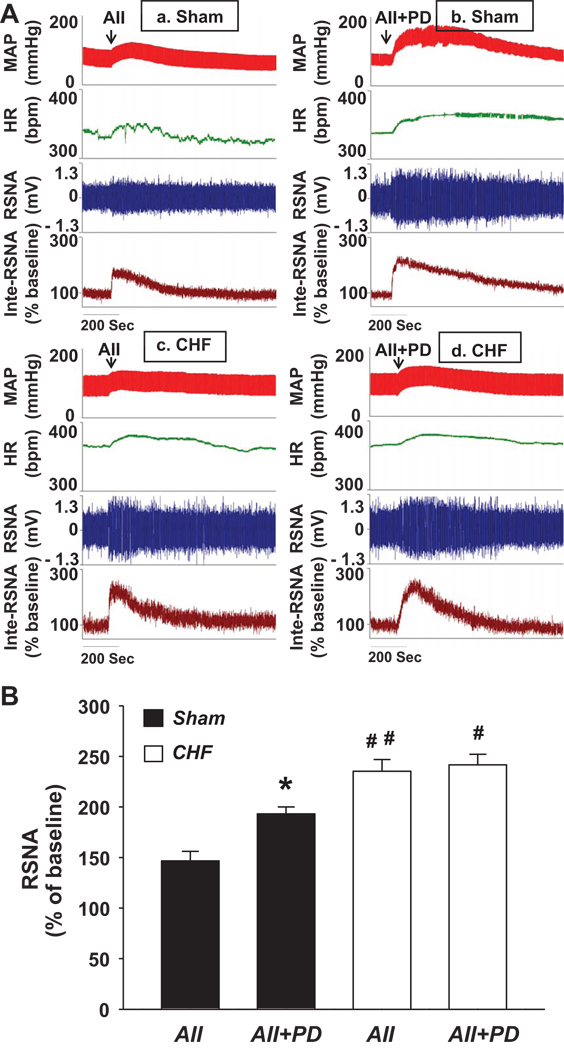

3. Activating AT1R by Ang II plus PD123319

Figure 4A shows the cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to microinjection of Ang II (50 pmol in 50 nL) plus PD123319 (1 nmol in 50 nL) unilaterally into the RVLM in sham and CHF rats. From Panels b and d of this figure it can seen that, in both sham and CHF rats, this treatment also produced an increase in the arterial blood pressure (ΔMAP: 38.2 ± 6.5 mmHg for Sham, 31.6 ± 4.7 mmHg for CHF; P < 0.05), HR (ΔHR: 31.4 ± 8.1 bpm for Sham, 27.6 ± 5.8 bpm for CHF; P < 0.05), and RSNA (ΔRSNA: 193.2 ± 6.8 % of baseline for Sham, 241.6 ± 10.4 % of baseline for CHF; P < 0.05), suggesting that selective stimulation of AT1R in the RVLM also evoked a cardiovascular and sympathetic excitation. Compared with Ang II alone, microinjection of Ang II plus PD123319 into the RVLM elicited a larger hypertension and sympatho-excitation only in sham but not in CHF rats. The mean data of RSNA responses to the activation of AT1R and AT2R, or only AT1R, are shown in Figure 4B.

Figure 4.

Different sympathetic responses to RVLM Ang II alone or Ang II plus PD123319 treatment in sham and CHF rats. Panel A shows a representative trace and panel B is the group data showing the maximal change in RSNA. *P < 0.05 compared with the Ang II group; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 compared with the corresponding group in sham rats. n = 7–8 per group.

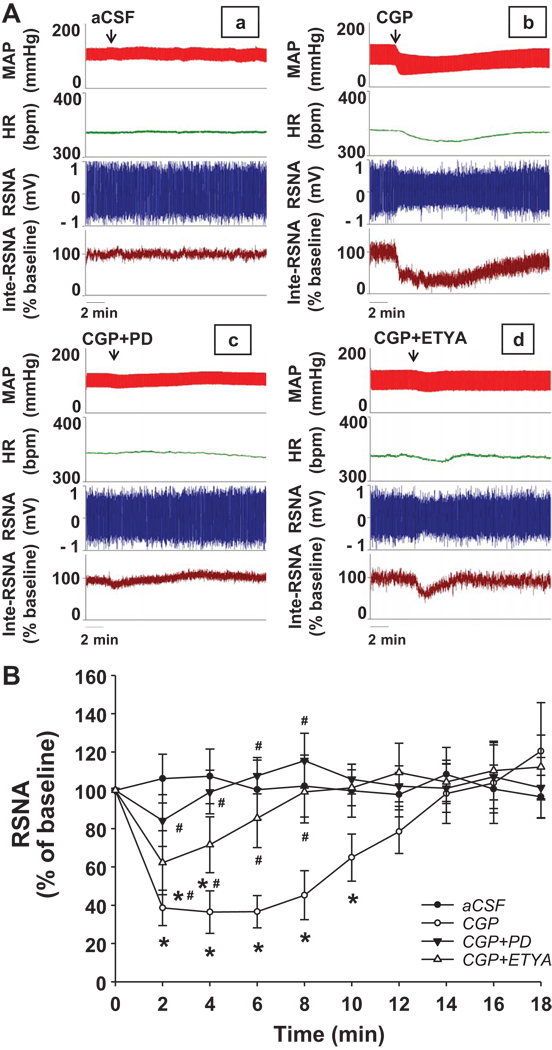

4. Activating AT2R by CGP42112

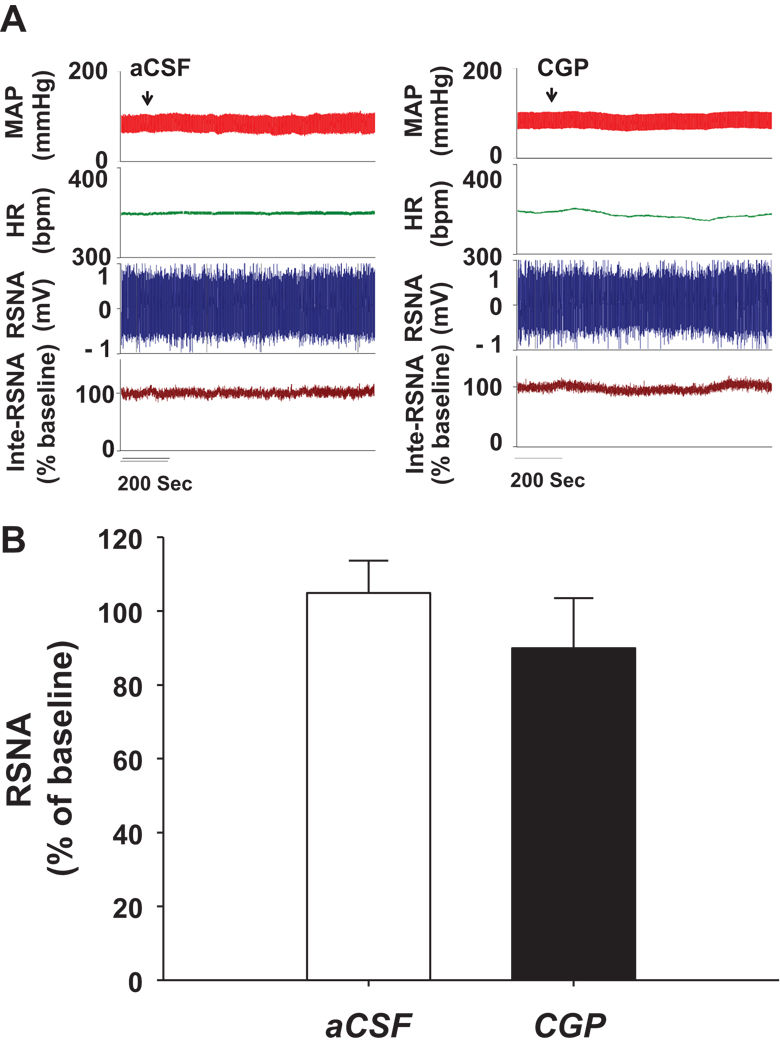

Figure 5 shows the cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to microinjection of CGP42112 unilaterally into the RVLM in normal rats. CGP42112 (50 pmol in 50 nL) evoked a decrease in blood pressure (ΔMAP = −31.3 ± 4.6 mmHg; P < 0.05), heart rate (ΔHR = −26.7 ± 5.2 bpm; P < 0.05), and RSNA (ΔRSNA = 36.4 ± 11.1 % of baseline; P < 0.05), suggesting that activation of AT2R in the RVLM depressed sympathetic outflow. These effects of CGP42112 were abolished by pretreatment with PD123319, a specific AT2R antagonist. Moreover, pretreatment with 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA, a general inhibitor of Arachidonic Acid metabolism, 10 pmol in 50 nL) partially attenuated the CGP42112 induced hypotension, tachycardia, and sympatho-inhibitory responses. In the CHF rats, we did not find significant changes in blood pressure (ΔMAP = −5.1 ± 3.2 mmHg, P > 0.05), heart rate (ΔHR = −3.8 ± 4.4 bpm, P > 0.05), and RSNA (ΔRSNA = 89.9 ± 13.6 % of baseline, P > 0.05) after CGP42112 was microinjected into the RVLM, which is shown in the figure 6.

Figure 5.

Effects of microinjection of CGP42112 into the RVLM on sympathetic outflow, heart rate and arterial pressure in sham rats. Panel A shows a representative trace and panel B is the time course of group data showing the change in RSNA. *P < 0.05 compared with the aCSF group; #P < 0.05 compared with the CGP42112 group. n = 7–8 per group.

Figure 6.

Effects of microinjecting CGP42112 into the RVLM of CHF rats on sympathetic outflow, heart rate and arterial pressure. Panel A shows a representative trace and panel B is the group data showing the maximal change in RSNA. n = 7 per group.

Discussion

It has long been known that activation of AT1R in the RVLM evokes an increase in sympathetic outflow4, 17. AT1R activation in the RVLM plays a critical role in the sympatho-excitation in the CHF state6. However, the role of AT2R in modulation of sympathetic outflow in CHF is completely unknown. The major novel findings from the present study are that (1) AT2R protein expression in the RVLM of CHF rats was significantly lower than that in sham rats; (2) microinjection of Ang II plus the AT2R antagonist, PD123319, into the RVLM produced a larger hypertension and sympatho-excitation than Ang II alone in sham but not in CHF rats; (3) microinjection of the AT2R agonist, CGP42112, into the RVLM evoked hypotension, bradycardia, and sympatho-inhibition in sham rats, but not in CHF rats. These results document that AT2R expression in the RVLM is down regulated in CHF rats and that AT2R stimulation in the RVLM exhibited an inhibitory effect on sympathetic outflow in the normal condition. These data suggest that suppressed AT2R signaling may be involved in the sympathetic over activity in the CHF state.

Sympathetic nerve activity is regulated at several central loci, including the subfornical organ (SFO), the area postrema (AP), the PVN in the hypothalamus and the NTS and RVLM in the medulla18. Of these structures the RVLM is an important region in maintaining tonic activity of sympathetic nerve outflow19. By directly projecting to sympathetic preganglionic neurons of the spinal cord and receiving inputs from other sympathetic-related central nuclei, the RVLM acts as a final common pathway in transferring signals from more rostral structures to peripheral sympathetic nerves. A series of studies from our laboratory6, 20 have demonstrated that the up-regulated AT1R expression and the enhanced AT1R related intracellular signaling pathway in the RVLM play a critical role in the sympatho-excitation in the CHF condition, similar to that observed in hypertension7. Interestingly, in the current study, we found that while AT1R protein expression in the RVLM of CHF rats was up- regulated, the AT2R was significantly down-regulated and therefore greatly increased the ratio of AT1R to AT2R protein expression from 2.1 ± 0.4 in sham to 13.8 ± 0.7 in CHF (figure 1). Even though the physiological roles of central AT2R in whole animals are unclear, the patch clamp data from the cultured individual neurons of hypothalamus and brainstem clearly demonstrated an increase in the potassium current induced by this receptor11, 21, a effect contrary to that of the AT1R on neuronal channel function22. The functions and intracellular signaling pathways of the AT2R in most peripheral tissues and organs also are opposite to that of the AT1R. For example, stimulating AT2R induces vasodilation, stimulates nitric oxide production, and inhibits reactive oxygen species generation23. Taken together these data led us to postulate that the balance between AT1R and AT2R in the RVLM may be the critical to maintain sympathetic tone in normal conditions, and that the down-regulated AT2R, combined with the up-regulated AT1R in the RVLM may contribute to the sympatho-excitation in the CHF state. The mechanism for the ameliorating effects of AT2R stimulation on the responses to AT1R stimulation in the present experiments is not completely clear, however a potential decrease in neuronal potassium current induced by the down regulation of AT2R expression (i.e. dominance of AT1R expression) may imply facilitated neuronal excitability and exaggerated sympathetic outflow.

Interestingly microinjection of CGP42112, a specific AT2R agonist, into the RVLM evoked a significant hypotension, bradycardia, and decreased RSNA a completely opposite effect to the well-known role induced by central AT1R stimulation. These data provide direct evidence showing physiological significance of brain AT2R in the regulation of autonomic function. Moreover, the effects of AT2R in the RVLM were completely blocked by pretreatment with the AT2R antagonist, PD123319, demonstrating the specificity of this effect. Support for our hypothesis comes from mice lacking AT2R’s. Siragy et al.24 reported that AT2R-null mice had slightly elevated systolic blood pressure compared with that of wild-type control mice. Infusion of a subpressor dose of Ang II failed to induce a change of blood pressure in wild-type mice but significantly increased in blood pressure in AT2R knock-out mice. Moreover, Li et al.25 found that injection of Ang II into the cerebral ventricle evoked a larger increase in blood pressure in AT2R knock-out mice than that in wild type mice. In wild type mice central injection of Ang II plus PD123319 initiated a greater pressor response than that induced by Ang II alone. The majority of neuronal AT2R intracellular signaling pathways are mediated via different mediators from that of AT1R.

It has been demonstrated in neurons cultured from neonatal rat hypothalamus and brainstem, that inhibitory G proteins, PLA2, and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) are involved in the AT2R-dependent increase in potassium current21, 26, 27. AT2R activation stimulates PP2A activity28 and PP2A may directly participate in a dephosphorylation-mediated activation of the potassium channel. Zu et al.13 explored the involvement of a series of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolites in the AT2R-evoked increase in the potassium current in cultured neurons, and demonstrated that the pathway of AA metabolism is responsible for the modulation of potassium currents by AT2R. Indeed, in the current study, we found that pretreatment with ETYA, a general inhibitor of AA metabolism, partially attenuated the activation of AT2R induced suppression of sympathetic outflow (figure 5).

In the current study we found that microinjection of Ang II into the RVLM evoked a significant pressor, tachycardia, and sympatho-excitation in both sham and CHF rats, with a greater sympathetic response in CHF rats (figure 3). This differential effect of Ang II in the RVLM between sham and CHF animals appears to be due to the increased AT1R and decreased AT2R expressions in the CHF state compared with sham. Indeed, when Ang II was microinjected into the RVLM following pretreatment with PD123319 we found enhanced sympathetic responses only in sham but not in CHF rats (figure 4). These data suggest that, in the normal condition, simultaneously activating AT1R and AT2R in the RVLM produced smaller responses than that induced by stimulating AT1R alone. This implies that the opposing effects of AT2R and AT1R in the RVLM play a role in the maintenance of sympathetic outflow. On the other hand, in the CHF state, loss of this opposing influence due to the down regulation of AT2R may contribute to the sympatho-excitation.

Stimulation of AT2R in the RVLM by CGP42112 induced inhibition of cardiovascular activity and sympathetic outflow exhibits regional specificity. In normal rats, microinjection of CGP42112 into the vicinity of RVLM, which had no response to L-glutamate, evoked no change in blood pressure, heart rate, and RSNA. Interestingly, microinjection of CGP42112 into the caudal ventrolateral medulla where L-glutamate often generates inhibition of sympathetic nerve activity, evoked pressor and sympatho-excitatory effects (data not shown).

Perspectives

In a recently published paper29, we reported a decrease in nocturnal arterial pressure coincident with a decrease in urine concentration of noradrenaline and 24-hour noradrenaline excretion in normal conscious rats following RVLM over expression of AT2R by Adenoviral transfection. In the current experiment, we documented the negative influence of stimulating endogenous AT2R in the RVLM on sympathetic outflow in normal rats and the weakened AT2R pathway in the RVLM of heart failure rats, providing further insights into the physiological and pathological significance of AT2R in the neural control of autonomic and circulatory function. In the future experiments, we will observe the potential beneficial effects of AT2R over expression in the RVLM of CHF rats on heart failure state by AT2R-Adenoviral transfection. Moreover, the first selective nonpeptide AT2R agonist, Compound 21, has been synthesized recently by Wan et al. 30. It is intriguing to speculate substances such as this may hold potential and promise for the treatment of such diseases characterized by sympatho-excitation such as CHF and hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the expert technical assistance Li Yu. The authors also appreciate the donation of brain samples by Dr. George Rozanski.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association National Center (Award Number: 0635007N) and in part by NIH grants PO-1-HL-62222, and RO-1-HL-38690.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Just H. Peripheral adaptations in congestive heart failure: a review. Am J Med. 1991;90 doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90269-4. 23S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye DM, Lefkovits J, Jennings GL, Bergin P, Broughton A, Esler MD. Adverse consequences of high sympathetic nervous activity in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontes MA, Martins Pinge MC, Naves V, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Lopes OU, Khosla MC, Santos RA. Cardiovascular effects produced by microinjection of angiotensins and angiotensin antagonists into the ventrolateral medulla of freely moving rats. Brain Res. 1997;750:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirooka Y, Potts PD, Dampney RA. Role of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in mediating the sympathoexcitatory effects of exogenous and endogenous angiotensin peptides in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rabbit. Brain Res. 1997;772:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SH, Hsu KS, Huang CC, Wang LL, Ou CC, Chan JY. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced pressor effect via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Circ Res. 2005;97:772–780. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185804.79157.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:937–944. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146676.04359.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito S, Komatsu K, Tsukamoto K, Kanmatsuse K, Sved AF. Ventrolateral medulla AT1 receptors support blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2002;40:552–559. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000033812.99089.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grady EF, Sechi LA, Griffin CA, Schambelan M, Kalinyak JE. Expression of AT2 receptors in the developing rat fetus. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:921–933. doi: 10.1172/JCI115395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsutsumi K, Saavedra JM. Characterization and development of angiotensin II receptor subtypes (AT1 and AT2) in rat brain. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R209–R216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenkei Z, Palkovits M, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Expression of angiotensin type-1 (AT1) and type-2 (AT2) receptor mRNAs in the adult rat brain: a functional neuroanatomical review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:383–439. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang J, Sumners C, Posner P. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-modulated changes in potassium currents in cultured neurons. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C607–C616. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang J, Richards EM, Posner P, Sumners C. Modulation of the delayed rectifier K+ current in neurons by an angiotensin II type 2 receptor fragment. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C278–C282. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.1.C278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu M, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Moore JM, Gelband CH, Sumners C. Angiotensin II increases neuronal delayed rectifier K(+) current: role of 12-lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2494–2501. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuura T, Kumagai H, Onimaru H, Kawai A, Iigaya K, Onami T, Sakata K, Oshima N, Sugaya T, Saruta T. Electrophysiological properties of rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons in angiotensin II 1a receptor knockout mice. Hypertension. 2005;46:349–354. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000173421.97463.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao L, Schultz HD, Patel KP, Zucker IH, Wang W. Augmented input from cardiac sympathetic afferents inhibits baroreflex in rats with heart failure. Hypertension. 2005;45:1173–1181. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168056.66981.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palkovits M, Brownstein MJ. Maps and Guide to Microdissection of the Rat Brain. New York: Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Averill DB, Tsuchihashi T, Khosla MC, Ferrario CM. Losartan, nonpeptide angiotensin II-type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist, attenuates pressor and sympathoexcitatory responses evoked by angiotensin II and L-glutamate in rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Res. 1994;665:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dampney RA. The subretrofacial vasomotor nucleus: anatomical, chemical and pharmacological properties and role in cardiovascular regulation. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:197–227. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Simvastatin therapy normalizes sympathetic neural control in experimental heart failure: roles of angiotensin II type 1 receptors and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation. 2005;112:1763–1770. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.552174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang J, Posner P, Sumners C. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation of neuronal K+ currents involves an inhibitory GTP binding protein. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1389–C1397. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelband CH, Zhu M, Lu D, Reagan LP, Fluharty SJ, Posner P, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Functional interactions between neuronal AT1 and AT2 receptors. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2195–2198. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaschina E, Unger T. Angiotensin AT1/AT2 receptors: regulation, signalling and function. Blood Press. 2003;12:70–88. doi: 10.1080/08037050310001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siragy HM, Inagami T, Ichiki T, Carey RM. Sustained hypersensitivity to angiotensin II and its mechanism in mice lacking the subtype-2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6506–6510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Iwai M, Wu L, Shiuchi T, Jinno T, Cui TX, Horiuchi M. Role of AT2 receptor in the brain in regulation of blood pressure and water intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H116–H121. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu M, Neubig RR, Wade SM, Posner P, Gelband CH, Sumners C. Modulation of K+ and Ca2+ currents in cultured neurons by an angiotensin II type 1a receptor peptide. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1040–C1048. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu M, Gelband CH, Moore JM, Posner P, Sumners C. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation of neuronal delayed-rectifier potassium current involves phospholipase A2 and arachidonic acid. J Neurosci. 1998;18:679–686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00679.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang XC, Sumners C, Richards EM. Angiotensin II stimulates protein phosphatase 2A activity in cultured neuronal cells via type 2 receptors in a pertussis toxin sensitive fashion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;396:209–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1376-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao L, Wang W, Wang W, Li H, Sumners C, Zucker IH. Effects of angiotensin type 2 receptor overexpression in the rostral ventrolateral medulla on blood pressure and urine excretion in normal rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:521–527. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan Y, Wallinder C, Plouffe B, Beaudry H, Mahalingam AK, Wu X, Johansson B, Holm M, Botoros M, Karlen A, Pettersson A, Nyberg F, Fandriks L, Gallo-Payet N, Hallberg A, Alterman M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of the first selective nonpeptide AT2 receptor agonist. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5995–6008. doi: 10.1021/jm049715t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.