Abstract

This study aimed to identify clinically meaningful profiles of pain coping strategies used by youth with chronic abdominal pain (CAP). Participants (n = 699) were pediatric patients (ages 8–18 years) and their parents. Patients completed the Pain Response Inventory (PRI) and measures of somatic and depressive symptoms, disability, pain severity and pain efficacy, and perceived competence. Parents rated their children’s pain severity and coping efficacy. Hierarchical cluster analysis based on the 13 PRI subscales identified pain coping profiles in Sample 1 (n = 311) that replicated in Sample 2 (n = 388). Evidence was found of external validity and distinctiveness of the profiles. The findings support a typology of pain coping that reflects the quality of patients’ pain mastery efforts and interpersonal relationships associated with pain coping. Results are discussed in relation to developmental processes, attachment styles, and treatment implications.

Introduction

Theory and research on coping, defined as efforts to manage demands appraised as taxing or exceeding one’s resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), have made important contributions to understanding the experience of pain. The coping literature has identified numerous specific ways of coping with pain (e.g., support-seeking, problem-solving, acceptance) that are typically classified into a smaller number of higher order categories (e.g., approach versus avoidance; active versus passive) and examined in relation to health outcomes. For example, the higher order category of passive coping has been associated with relatively poor outcomes for pain patients (e.g., Brown, Nicassio, & Wallston, 1989; Smith, Wallston, & Dwyer, 2003).

However, hierarchical classification of ways of coping may oversimplify the complexity of the construct and obscure the importance of individual coping strategies. For example, Jensen and colleagues (Jensen, Turner, & Romano, 1992) found that the individual scales of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ) provided more information regarding the relation between coping and adjustment to chronic pain than did the composite higher-order CSQ indices. Another challenge in the hierarchical classification of coping is that the function of a specific way of coping may vary across individuals and situations, making it difficult to assign that coping activity to a single higher order category. For example, we found that pain catastrophizing cross-loaded on active and passive higher order coping factors, suggesting that catastrophizing can serve both as a form of disengagement (a passive function) and as an appeal for help (an active function) (Walker, Smith, Garber, & Van Slyke, 1997).

An alternative to existing systems for the hierarchical classification of coping is to identify profiles summarizing the coping activities of subgroups of patients across multiple specific ways of coping through the use of cluster analytic techniques (cf. Smith & Wallston 1996). This approach not only retains information about specific ways of coping, but also captures potential interactions among concurrent coping activities. Then, to examine the external validity of the empirical solution generated through the cluster analysis, the different profiles can be compared with regard to other theoretically relevant variables not included in the original cluster analysis.

The current study aimed to identify clinically meaningful profiles of the ways pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain (CAP) cope with pain. Profiles of chronic pain patients previously have been developed with diverse sets of constructs (e.g., Burns et al., 2001; Denison et al., 2007; Scharff et al., 2005; Turk & Rudy, 1990). For example, Turk and Rudy (1990) identified subgroups of pain patients based on several constructs including pain severity, affective distress, and responses by significant others. In contrast, our goal was to identify patterns of coping activity that may mediate the relation between pain and health outcomes, and therefore we based our classification only on coping variables. We validated the profiles by examining their relation to other patient characteristics, including pain self-efficacy beliefs, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment. Deriving our typology from specific ways of coping should help to identify profiles associated with patient behaviors that influence pain outcomes and could be targeted in treatment interventions.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 699) consisted of two cohorts of consecutive new patients referred to the Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinic of Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital for evaluation of chronic abdominal pain (n for Sample 1 = 311; n for Sample 2 = 388). Samples 1 and 2 were recruited consecutively using the same procedure. Patients were eligible if they were between the ages of 8 and 18 years and had been referred by their primary care provider for subspecialty evaluation following a medical evaluation that revealed no evidence of organic disease. The samples did not differ with respect to age (Sample 1: M = 11.4 years, SD = 2.41; Sample 2: M = 11.8 years, SD = 2.53). The majority of patients were female (Sample 1: 57%; Sample 2: 61%) and Caucasian (Sample 1: 95%; Sample 2: 91%). The remaining participants were African-American (4% in each sample) or other/unknown. Of the parents who participated, 93% were mothers. The majority of parents had completed high school. Two samples were obtained in order to assess whether results of the cluster analysis would replicate (i.e., be cross-validated) across independent samples.

Procedure

A trained research assistant met eligible families at the clinic prior to their medical evaluation, described the study, and obtained parental consent and patient assent for study participation. The research assistant read the questionnaire items to the patients who responded by selecting numbers on a response sheet. Parents completed questionnaires in another room. The study had the approval of the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Pain coping strategies

The Pain Response Inventory (PRI; Walker et al., 1997) is a 60-item self-report questionnaire that assesses children’s responses to abdominal pain. The PRI has thirteen subscales, each comprised of three to six items that describe a response to pain. The stem for each item is, “When you have a bad stomach ache, how often do you …” followed by a statement describing a possible response to pain (e.g., “try to do something to make it go away”). Responses range from never (0) to always (4), with higher scores indicating greater use of a particular strategy. The subscales (with sample items) include: Problem Solving (e.g., try to do something to make it go away); Seeking Social Support (e.g., ask someone for help); Rest (e.g., try to rest); Massage/Guard (e.g., rub your stomach to try to make it feel better); Condition-Specific Strategies (e.g., take some medicine); Minimizing Pain (e.g., tell yourself that it’s not that bad); Distract/Ignore (e.g., think of things to keep your mind off the pain); Acceptance (e.g., try to learn to live with it); Self-encouragement (e.g., tell yourself to keep going even though it hurts); Behavioral Disengagement (e.g., give up since nothing helps); Catastrophizing (e.g., think to yourself that it’s going to get worse); Self-isolation (e.g., stay away from people); and Stoicism (e.g., keep others from knowing how much it hurts). A mean score ranging from 0 to 4 is calculated for each subscale. Empirical validation of the measure and a list of all items for each subscale are reported by Walker et al. (1997). In the current study, with the exception of a single scale (Condition-Specific Strategies, alpha = .40), coefficient alpha levels of the subscales ranged from .71 to .90 for the total sample. All thirteen subscales of the PRI were used to examine clusters of coping strategies. Of the 699 research participants, 13 did not complete the PRI; these participants were removed from subsequent analyses, leaving a sample of 686 participants classified into coping profiles.

Pain intensity

Children’s pain during the last two weeks was assessed using the pain intensity item of the Abdominal Pain Inventory (API; Walker et al., 1997). Patients rated their typical pain intensity on an 11-point visual analogue scale ranging from no pain (0) to the most pain possible (10).

Somatic symptoms

The Children’s Somatization Inventory (CSI; Walker & Garber, 2003; Walker & Greene, 1989) was developed by Walker and colleagues to assess children’s nonspecific somatic symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness, chest pain). The CSI comprises thirty-five items representing symptoms from the DSM-III-R criteria for somatization disorder (APA, 1987) and from the somatization factor of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Derogatis et al., 1974). The item stem for the child-report CSI is “How much were you bothered by each symptom in the past 2 weeks,” with possible responses ranging from not at all (0) to a whole lot (4). A mean score across all items was calculated to aid interpretation, as mean scores correspond with the response options not at all (0), a little (1), some (2), a lot (3), and a whole lot (4). The CSI has good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Garber et al., 1991; Walker & Greene, 1989). Coefficient alpha was .90 in this sample.

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms. Twenty-six of the original twenty-seven items were administered (an item assessing suicidal ideation was omitted). Item scores range from 0 to 2, with a total score obtained by summing item scores. Higher scores indicate the presence of more depressive symptomatology. Coefficient alpha was .85 in this sample.

Functional disability

Children completed the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI; Claar & Walker, 2006; Walker & Greene, 1991) regarding the extent to which their daily activities had been disrupted due to pain during the past two weeks. The FDI consists of fifteen activities (e.g., walking up stairs, doing chores at home, reading or doing homework), preceded by the stem, “In the past two weeks, would you have had any physical trouble or difficulty doing these activities?” Item responses range from no trouble (0) to impossible (4). In this study, mean scores were computed, with higher scores indicating greater levels of impairment. Scores on the FDI have been reported to correlate significantly with measures of school absence and somatic symptoms (Walker & Greene, 1991). Estimates of three-month test-retest reliability exceed .60 among pediatric patients with abdominal pain, and high levels of internal consistency have been previously reported (Walker & Greene, 1991). Coefficient alpha for the FDI was .90 in this sample.

Perceived competence

Children’s perceived competence was assessed with the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1985). This measure requires children to select one of two opposite descriptors and endorse the extent to which it is true of them. We used three SPPC scales, each with six items: Global, School, and Social Competence. The Likert-type response format ranges from 1 to 4, with total scale scores ranging from 6 to 24. Harter (1982) reported acceptable levels of internal consistency and convergent validity for the SPPC. In this sample, internal consistency ranged from 0.76 (perceived social competence) to 0.82 (perceived global and school competence).

Pain beliefs and coping appraisals

Children completed the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ; Walker et al., 2005), a 32-item measure that assesses appraisals of pain seriousness and perceived efficacy in using problem- and emotion- focused pain coping strategies. Twenty items assess perceived seriousness of the pain condition (e.g., “My stomach aches mean I have a serious illness”). Six items each assess emotion-focused coping efficacy (e.g., “I know I can handle it no matter how bad my stomach hurts”) and problem-focused coping efficacy (e.g., “When I have a bad stomach ache, there are ways I can get it to stop”). Responses range from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (always true). Mean scores are created for each scale (pain seriousness, problem-focused coping efficacy, and emotion-focused coping efficacy). Internal consistency for the scales is adequate (Walker et al., 2005). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.76 to 0.88 for the PBQ scales.

Family stress

Parents reported the presence of family stressors using the 70-item Family Inventory of Life Events (FILE; McCubbin et al., 1982). The FILE is a checklist on which parents record the life events experienced by their family in the previous year. Each life event endorsed receives one point, and the total score reflects the number of family stressors. McCubbin et al. (1982) reported adequate reliability and construct validity for the FILE.

Results

Identification of coping profiles in Samples 1 and 2

Coping profiles were based on the 13 subscales of the Pain Response Inventory (PRI). First, we conducted exploratory hierarchical cluster analyses separately for each of the two samples using Ward’s method (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). We examined the viability of solutions ranging from two to ten clusters in each sample. Based on a comparison of the profiles of mean coping scores on the 13 PRI subscales, five clusters clearly replicated across the two samples. A sixth small cluster in Sample 2 did not replicate in Sample 1 but was conceptually interesting and therefore was retained, yielding a six cluster solution for further examination and replication. Pearson correlations of the mean coping scores across the 13 PRI subscales for the five clusters that were replicated in Samples 1 and Sample 2 ranged from .52 to .98 using standardized coping scores and from .70 to .98 using raw coping scores. In each instance, these correlations were notably higher for the paired replications across samples than they were for the profiles of any single cluster in one sample when it was paired with any of the other clusters in the other sample.

Development of a classification algorithm

Next, we combined the two cohorts into a single sample (n = 686) and created a common algorithm for profile classification. To this end, we first created mean centroid scores for each profile by averaging coping strategy scores across Sample 1 and Sample 2. For the sixth cluster, we used mean scores only from Sample 2, as this cluster was not evident in the initial exploratory hierarchical cluster analysis conducted with Sample 1. Mean centroid scores were rounded to the nearest half-unit.

Finally, for each case in the total sample, we calculated squared Euclidean distance scores of the individual’s coping strategy scores from each centroid mean. Each case was then assigned to the cluster from which the case had the lowest sum of distance scores. Comparison of case classification derived separately in Samples 1 and 2 with the classification based on mean centroid scores in the combined sample indicated a high rate of agreement, ranging from 71% to 92%, and thus supported the reliability of the six coping profiles. The membership of each of the six clusters included patients from each sample. For eight participants (1% of total sample), the lowest squared Euclidean distance score was greater than 3 standard deviations from the cluster mean to which it was closest. Because these cases were outliers even when compared to their closest cluster match, they were considered unclassified and were removed from further analyses. Cluster membership as determined by this algorithm was used to classify the remaining participants for all analyses reported below. (This algorithm can be used to classify participants in other studies using the PRI; SPSS syntax is available from the first author.)

Characterization of Coping Profiles

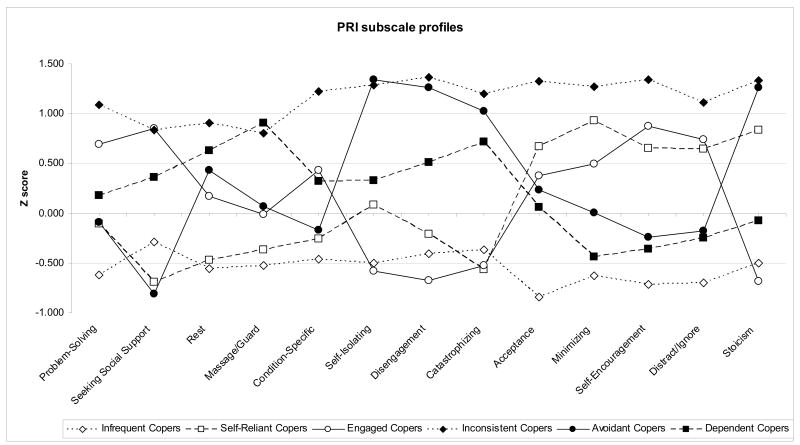

Figure 1 illustrates, for each of the six coping profiles, z-scores on the 13 PRI scales; for each profile group, peaks represent the group’s most frequent strategies and valleys represent the group’s least frequent strategies. Figure 1 also allows comparison of the relative frequency with which the groups used each of the thirteen coping scales in comparison to each other. Table 1 presents results of univariate ANOVAs comparing the raw scores of the six profile groups on the thirteen PRI subscales and indicates significant differences among the profile groups on each subscale. We also used ANOVAs to compare the profile groups on child-report and parent-report measures not used in constructing the profiles (Table 2). Because analyses designed to inform description of the clusters were exploratory, no correction was applied to the alpha level for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1.

Standardized scores for coping strategies characterizing each coping profile

Table 1.

PRI subscale means and standard deviations by coping cluster

| PRI subscale | Total (n = 699) | F | p | Infrequent Copers (n = 212) | Inconsistent Copers (n = 27) | Avoidant Copers (n = 72) | Dependent Copers (n = 135) | Self-reliant Copers (n = 97) | Engaged Copers (n = 135) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem-solving | 2.50 (.83) | 50.09 | .000 | 1.99 (.75)b | 3.40 (.51)c | 2.42 (.60)a | 2.65 (.67)e | 2.41 (.83)a | 3.07 (.69)d |

| Seeking social support | 2.14 (.93) | 76.19 | .000 | 1.87 (.78)c | 2.91 (.72)a | 1.39 (.73)b | 2.48 (.77)d | 1.50 (.69)b | 2.93 (.70)a |

| Rest | 2.32(.84) | 48.57 | .000 | 1.85 (.73)a | 3.07 (.67)b | 2.68 (.73) c | 2.84 (.61)b, c | 1.92 (.76)a | 2.46 (.78)d |

| Massage/guard | 1.78(1.11) | 56.21 | .000 | 1.19 (.86)a | 2.67 (1.07)b | 1.85 (1.10)c | 2.78 (.83)b | 1.37 (.90)a | 1.76 (1.06)c |

| Condition specific strategies | 2.08 (.68) | 32.79 | .000 | 1.77 (.60)a | 2.91 (.49)d | 1.97 (.63)b | 2.30 (.59)c | 1.91 (.64)a, b | 2.38 (.62)c |

| Self-isolation | 0.99 (.99) | 99.62 | .000 | 0.49 (.60)a | 2.26 (1.03)b | 2.31 (.96)b | 1.31 (.88)d | 1.07 (.88)c | 0.41 (.50)a |

| Disengagement | 0.76 (.75) | 107.58 | .000 | 0.45 (.46)b | 1.79 (.83)a | 1.71 (.78)a | 1.15 (.64)e | .61 (.61)d | 0.25 (.35)c |

| Catastrophizing | 1.35 (.92) | 95.22 | .000 | 1.01 (.70)a | 2.44 (1.01)c | 2.29 (.77)c | 2.00 (.79)d | 0.83 (.56)b | 0.87 (.60)a, b |

| Acceptance | 1.66 (.93) | 85.28 | .000 | .89 (.58)b | 2.89 (.63)c | 1.88 (.67)a | 1.72 (.72)a | 2.28 (.80)d | 2.01 (.90)a |

| Minimizing | 1.31 (.98) | 89.28 | .000 | 0.70 (.59)a | 2.56 (.87)b | 1.31 (.74)f | 0.89 (.63)e | 2.23 (.83)d | 1.80 (1.02)c |

| Self-encouragement | 2.11 (.95) | 121.76 | .000 | 1.43 (.66)b | 3.38 (.40)c | 1.88 (.70)a | 1.76 (.67)a | 2.73 (.75)e | 2.94 (.75)d |

| Distract/ignore | 2.33 (.87) | 84.47 | .000 | 1.72 (.69)c | 3.30 (.55)d | 2.17 (.68)b | 2.12 (.77)b | 2.90 (.65)a | 2.98 (.64)a |

| Stoicism | 1.35 (.98) | 140.98 | .000 | 0.86 (.63)b | 2.67 (.91)a | 2.59 (.73)a | 1.28 (.73)e | 2.17 (.81)d | 0.68 (.56)c |

Note. Within rows, means with different subscripts differ significantly at p<.05.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for psychosocial characteristics in the total sample and in each cluster

| Psychosocial Characteristic | Total (n = 699) | F | p | Infrequent Copers (n = 212) | Inconsistent Copers (n = 27) | Avoidant Copers (n = 72) | Dependent Copers (n = 135) | Self-reliant Copers (n = 97) | Engaged Copers (n = 135) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Child Report Variables | |||||||||

| Pain intensity | 5.61 (2.43) | 3.40 | .005 | 5.23 (2.36)a | 6.33 (3.06)b, c | 6.08 (2.32)b, c | 6.11 (2.60)c | 5.46 (2.06)a, b | 5.44 (2.44)a, b |

| Somatic symptoms | 0.66 (.41) | 19.99 | .000 | 0.53 (.33)a | 0.94 (.67)b | 0.89 (.40)b | 0.82 (.44)b | 0.65 (.36)c | 0.54 (.34)a |

| Functional disability | 0.74 (.63) | 20.32 | .000 | 0.57 (.50)a | 1.20 (.85)b, c | 1.25 (.74)b | 0.94 (.67)c | 0.59 (.50)a | 0.52 (.49)a |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.77 (6.41) | 35.18 | .000 | 7.56 (5.48)a | 12.57 (7.69)b, c | 14.23 (6.64)b | 11.38 (6.60)c | 7.94 (5.42)a | 4.99 (4.19)d |

| Appraisal of pain seriousness | 1.91 (0.70) | 21.61 | .000 | 1.82 (0.54)b | 2.09 (0.83)a | 2.24 (0.70)a | 2.24 (0.66)a | 1.73 (0.67)b | 1.55 (0.70)c |

| Emotion-focused coping efficacy | 2.46 (0.90) | 39.19 | .000 | 2.45 (0.73)c | 1.88 (0.97)a | 2.02 (0.70)a | 2.00 (0.91)a | 3.01 (0.65)b | 2.98 (0.77)b |

| Problem-focused coping efficacy | 1.95 (0.95) | 19.62 | .000 | 1.82 (0.79)a | 1.99 (1.05)a, b | 1.54 (0.87)c | 1.67 (0.85)a, c | 2.26 (1.01)b | 2.49 (0.88)d |

| Global competence | 19.59 (3.99) | 18.54 | .000 | 19.94 (3.64)a | 18.23 (4.80)b, c | 16.88 (4.33)c | 18.70 (4.20)b | 19.67 (3.62)a, b | 21.73 (2.79)d |

| School competence | 17.47 (4.46) | 9.23 | .000 | 17.47 (4.15)a, b | 16.46 (5.36)a, b, c | 15.66 (4.63)c | 16.61 (4.44)a, c | 18.07 (4.50)b | 19.35 (3.77)d |

| Social competence | 18.53 (3.91) | 5.99 | .000 | 18.74 (3.70)a | 17.64 (4.25)a, b | 16.75 (4.15)b | 18.22 (3.93)a | 18.51 (3.95)a | 19.68 (3.58)c |

|

Parent Report Variables | |||||||||

| Appraisal of the seriousness of child’s pain | 2.16 (0.58) | 3.18 | .008 | 2.10 (0.57)a | 2.23 (0.54)a, b | 2.27 (0.62)b, c | 2.34 (0.63)b | 2.15 (0.58)a, c | 2.08 (0.54)a |

| Appraisal of child’s emotion-focused coping efficacy | 2.24 (0.83) | 1.96 | .083 | 2.26 (0.79) | 2.24 (0.68) | 2.08 (0.81) | 2.12 (0.94) | 2.39 (0.87) | 2.28 (0.81) |

| Appraisal of child’s problem-focused coping efficacy | 1.46 (0.82) | 2.33 | .041 | 1.48 (0.81)a | 1.79 (0.74)a | 1.29 (0.88)b | 1.43 (0.80)a, b | 1.56 (0.73)a | 1.48 (0.82)a, b |

| Family life events | 7.04 (5.48) | 2.42 | .035 | 6.21 (5.58)a | 9.10 (6.73)b | 6.81 (5.13)a, b | 7.87 (5.35)a, b | 8.32 (5.43)b | 6.75 (5.31)a, b |

Note. Within rows, means with different subscripts differ significantly at p<.05.

Below we describe the coping pattern of each group as well as characteristics of the groups based on child- and parent-report measures used for external validation of the profiles. Each profile was given a descriptive name based on the highest and lowest frequency coping strategies within the profile itself and in comparison to the other profiles.

Avoidant Copers

The profile for a cluster of 72 patients (10% of the sample) had peaks on the Self Isolation and Stoicism scales and a notable valley on the Seeking Social Support scale, indicating that they frequently responded to pain by avoiding social contact and trying to keep others from knowing how they felt. The PRI profile also indicated that they catastrophized about their pain and rarely used self-encouragement or distraction strategies to directly confront their pain. Patients in this Avoidant Copers group reported high levels of disability on the FDI and low levels of pain efficacy on the PBQ. Compared to most other groups, Avoidant Copers also had significantly higher levels of depressive and somatic symptoms, and lower perceived global, school and social competence.

Dependent Copers

The profile for another group of patients (n = 135; 19%) had peaks on the Massage/Guard and Rest scales, indicating that they exhibited considerable pain behavior. They reported relatively high levels of catastrophizing about pain. In comparison to Avoidant Copers (who also catastrophize), these patients reported significantly more support-seeking and significantly less self-isolation and stoicism. We labeled this group, Dependent Copers. Similar to the Avoidant Copers, Dependent Copers reported relatively high levels of pain intensity and somatic symptoms, high levels of pain seriousness, and low levels of pain coping efficacy on the PBQ. However, parents of Dependent Copers rated their children as having lower levels of problem-focused pain coping efficacy than children in any other group. Dependent Copers had relatively high scores for disability on the FDI and for depressive symptoms on the CDI, but these scores were significantly lower than those of Avoidant Copers. Moreover, Dependent Copers had significantly higher perceived global and social competence than Avoidant Copers.

Self-Reliant Copers

This cluster of patients (n = 97; 14%) was characterized by frequent use of accommodative coping strategies; their profile had peaks on the Acceptance, Minimizing Pain, and Self-Encouragement scales. Because this cluster also reported significantly less support-seeking than any group except Avoidant Copers, we labeled it, Self-Reliant Copers. Along with two other groups described below, these patients described relatively low levels of somatic symptoms, functional disability, depressive symptoms, and appraisals of pain seriousness in comparison to the Avoidant and Dependent Copers. Self-Reliant Copers reported significantly greater problem- and emotion-focused pain coping efficacy than most other groups.

Engaged Copers

One cluster (n = 135; 19%) had peaks on scales assessing constructive individual coping efforts including Problem-Solving, Self-Encouragement and Distraction as well as a peak on the Seeking Social Support scale. Because they engaged both personal and interpersonal resources for coping, we labeled this group Engaged Copers. Engaged Copers rated their pain intensity in the average range, but they viewed their pain as significantly less serious than any other group. In addition, their perceived efficacy in problem-focused coping was significantly higher than any other group. Their perceived global, academic, and social competences were significantly higher, and their level of depressive symptoms was significantly lower than that of any other group.

Infrequent Pain Copers

The profile representing the most patients (n = 212; 30%) reported that they rarely used any of the pain coping strategies. Compared to patients in most other groups, these Infrequent Pain Copers reported lower abdominal pain intensity and appraised their pain as significantly less serious. Infrequent Copers also reported very low levels of somatic symptoms, disability and depression.

Inconsistent Copers

The cluster with the fewest patients (n = 27; 4%) had high scores on all 13 PRI coping strategies. We labeled this profile, Inconsistent Copers, because they endorsed frequent use of strategies that are inconsistent with each other. For example, their personal coping activities included high levels of both catastrophizing and self-encouragement and their interpersonal coping activities included high levels of both self-isolation and support-seeking.

Concordance between parents’ and children’s reports on the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire

We further characterized the profiles by examining, for each of the six cluster groups, the level of concordance between parents and their children on parent-report and self-report versions of the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire. Parents of Engaged, Self-Reliant, and Infrequent Copers rated their children’s pain as being significantly more serious than did the children themselves. Moreover, these parents’ ratings of their children’s problem-focused and emotion-focused pain self-efficacy were significantly lower than their children’s self-ratings. The ratings of problem-focused pain self-efficacy by parents of children in the Dependent Copers group also were lower than their children’s self-ratings. No significant differences in parents’ and children’s ratings of pain seriousness and levels of children’s pain self-efficacy were found in the Avoidant and Inconsistent Copers groups.

Demographic characteristics of the coping profiles

Table 3 presents demographic characteristics of the six coping profile groups. The average pain duration exceeded one year and did not differ significantly across profile groups. The profile groups differed significantly by child gender, with the highest percentage of females in the Dependent Copers profile (74.1%) and the lowest percentage of females in the Self-Reliant Copers profile (46.4%). The groups also differed significantly by child age, with the youngest children in the Engaged Copers group (mean = 10.7 years, SD = 1.9) and the oldest children in the Avoidant group (mean = 12.86 years, SD = 2.5). The profiles did not differ with respect to the level of education of the participating parents.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics by cluster

| Total (n = 699) | Infrequent Copers (n = 212) | Inconsistent Copers (n = 27) | Avoidant Copers (n = 72) | Dependent Copers (n = 135) | Self-reliant Copers (n = 97) | Engaged Copers (n = 135) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child age in years mean (SD) | 11.60 (2.47) | 11.23 (2.24)a,b,d | 11.56 (2.71)a,b,c,d | 12.86 (2.48)c | 11.92 (2.64)a,c | 12.32 (2.66)c | 10.70 (1.94)b,d |

| Child sex percentage female | 59.2% | 59.9%a | 59.3%a,b,c | 55.6%a | 74.1%b | 46.4%c | 56.3%a |

| Child pain duration in months mean (SD) | 19.52 (24.28) | 18.89 (22.68)a | 20.60 (32.98)a | 22.68 (28.02)a | 20.47 (25.10)a | 18.63 (27.98)a | 18.80 (19.67)a |

| Parents with post- high school education percentage | 66.4% | 64.9%a | 50.0%a | 62.9%a | 62.8%a | 68.6%a | 75.4%a |

Note. Within rows, means or percentages with different subscripts differ significantly at p<.05.

Discussion

This study developed a typology of pain coping by applying cluster analytic techniques to data from several hundred pediatric chronic abdominal pain (CAP) patients. Based on patients’ responses to the 13 scales of the PRI, we identified and replicated pain coping profiles and validated these against patient and parent-report measures not used in developing the profile clusters. The profiles were associated with patients’ somatic and depressive symptoms, functional disability, pain self-efficacy beliefs, and perceived social, academic, and global competence. Study results suggest that the profiles capture meaningful patterns of children’s responses to pain that have implications for understanding the development of chronic pain and differences in patients’ treatment needs.

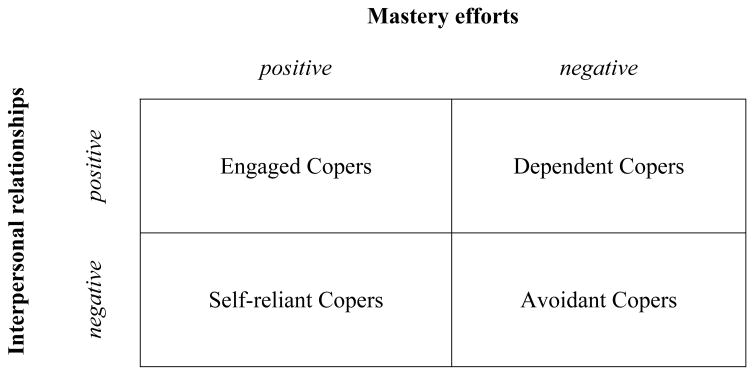

Skinner and colleagues (Skinner et al., 2003; 2007) proposed that coping can be conceptualized on several levels, ranging from specific instances of coping to adaptive processes that intervene between stress and outcomes. The pain coping profiles identified here represent a conceptual level intermediate between these. As shown in Figure 2 and described below, we propose that the pain coping profiles can be classified according to the quality of two higher order adaptive processes: mastery efforts and interpersonal relationships associated with pain.

Figure 2.

Mastery efforts and interpersonal relationships reflected in PRI coping profiles

Avoidant Copers were characterized by poor mastery efforts and withdrawal from interpersonal relationships when dealing with pain. They appeared to have given up, as they catastrophized, disengaged from efforts to manage pain, and rarely used self-encouragement or distraction. Moreover, they isolated themselves from others and tried not to let anyone know how they were feeling. Measures used to validate the profiles indicated that this group viewed their pain as very serious and their pain efficacy as quite low. Thus, they appraised abdominal pain as a significant threat that exceeded their coping resources. These Avoidant Copers had the highest scores on functional disability and depressive symptoms. It is possible that their depression contributed to their tendency to catastrophize and withdraw in response to pain. This pattern of responding to pain, in turn, is likely to exacerbate depression. Indeed, the characteristics of this profile are consistent with the downward spiral of pain-associated disability syndrome described by Zeltzer and colleagues (Bursch et al., 1998; Hyman et al., 2002). The finding that Avoidant Copers had the lowest scores of all groups on perceived social, academic, and global competence suggests that this profile may be associated with poor adaptation across several salient domains of child development.

Dependent Copers were similar to Avoidant Copers in their infrequent mastery efforts. However, the groups differed in their interpersonal relationships associated with pain. Compared to Avoidant Copers, Dependent Copers reported more support-seeking and visible pain behavior. The communal model of coping (Sullivan et al., 2000) suggests that catastrophizing can elicit support from others that, in turn, may reinforce disability. This possibility is consistent with our finding that Dependent Copers, who reported both catastrophizing and support-seeking, had high levels of disability and very low pain efficacy. Parents of Dependent Copers rated their children’s problem-focused pain self-efficacy even lower than did the children themselves. Dependent Copers had a higher proportion of females than the other profiles, perhaps reflecting the greater cultural acceptability of pain behavior and support-seeking among girls than boys (Myers et al., 2003). Interestingly, although social support may have reinforced the disability of Dependent Copers, it also may have served as a buffer against depression. That is, despite similar levels of pain intensity, the support-seeking Dependent Copers had significantly lower levels of depression than the self-isolating Avoidant Copers.

Self-Reliant Copers were characterized by high pain mastery efforts and avoidance of social contact during pain episodes. These patients were stoic, attempting to master pain without the assistance or knowledge of others. They made frequent use of acceptance, minimizing pain, and self-encouragement. Self-reliant Copers reported significantly higher levels of pain efficacy than Avoidant Copers or Dependent Copers. The higher proportion of males in the Self-Reliant group compared to other groups may reflect cultural expectations regarding suppression of pain expression by males (Unruh, 1996). Stoicism aimed at concealing one’s pain from others is associated with depression in adult pain patients (Yong, 2006). This observation is consistent with our finding that Self-Reliant Copers had significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than Engaged Copers, a group characterized not only by mastery efforts but also by seeking social support.

Engaged Copers were similar to Self-Reliant Copers in that their profile reflected efforts to gain mastery over pain. In contrast to Self-Reliant Copers, however, Engaged Copers frequently sought social support. Moreover, the two groups differed in the nature of their mastery efforts. Engaged Copers emphasized problem-solving and condition-specific strategies that reflect direct efforts to reduce pain, whereas Self-Reliant Copers reported significantly higher levels of stoicism and minimizing pain, suggesting that their mastery efforts focused on emotion regulation. Consistent with this view, Engaged Copers rated their problem-focused coping efficacy significantly greater compared to Self-Reliant Copers. The Engaged Coping profile appeared to represent a resilient response to pain, as it was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and disability as well as significantly higher perceived academic, social and global competence than any other group.

Two profiles did not appear to reflect the quality of patients’ mastery efforts or interpersonal relationships associated with pain. Infrequent Copers rarely engaged in any behaviors assessed by the PRI. Their ratings of pain intensity and seriousness were quite low, indicating that, for this group, pain did not constitute a stressor that required significant coping efforts. Inconsistent Copers, on the other hand, represented a very small group (4% of the sample) that endorsed frequent use of all coping strategies, suggesting either a response bias on the PRI or non-strategic, indiscriminant coping activities. This group also reported considerable distress and may have been trying everything and anything to deal with their pain.

Developmental theory proposes that children’s prior adaptation influences their subsequent adaptation (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995). Thus, children’s strategies for coping with pain may originate in their early interactions with caregivers at times of discomfort. As described by Bowlby (1967/1997), the nature of those interactions during infancy and early childhood give rise to relatively stable mental representations (“internal working models”) regarding the availability and responsivity of others as well as one’s own self-worth and efficacy. Children with a secure attachment style, characterized by positive models of self and other, exhibit more adaptive appraisals and coping behavior in the face of threat, whereas children with insecure attachment styles, characterized by negative models of self, other, or both, exhibit exaggerated negative appraisals and less adaptive coping behavior. Thus, a secure attachment style may provide a foundation for the development of Engaged Copers who have high pain self-efficacy and actively recruit both personal and interpersonal resources for coping with pain. In contrast, insecure attachment styles might predispose children to develop an Avoidant, Dependent, or Self-Reliant pain coping profile. Similarly, recent literature suggests that adult attachment styles may influence pain appraisal, coping, and health care seeking by adults with chronic pain (McWilliams & Asmundson, 2007; Meredith et al., 2007; Porter et al., 2007). Thus, attachment theory may provide a useful framework for a developmental model of the origins of pain coping.

The utility of a specific coping activity depends on the context and, therefore, particular ways of coping are not inherently good or bad (Compas et al., 2001; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Nonetheless, it is reasonable to expect that activities associated with the Engaged Coping profile would enhance personal and interpersonal resources for future coping with pain and other stressors, whereas activities associated with the Avoidant Coping profile might undermine coping resources and overall adaptation. This hypothesis should be tested in longitudinal studies comparing individuals with these different coping profiles with respect to trajectories of change over time in impairment, psychological adjustment, academic and occupational attainment, and other indices of adaptation.

Our finding that both Avoidant and Dependent Copers had relatively high levels of symptoms and disability is consistent with the developmental principle of equifinality, i.e., that a diversity of paths may lead to the same outcome (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996). Therefore, it may be useful to tailor treatments for CAP to address specific mechanisms and coping preferences associated with each coping profile. For example, a family intervention (e.g., Robins et al., 2005; Sanders et al., 1994) might be especially effective with Dependent Copers, whereas the high level of depressive symptoms in Avoidant Copers suggests that they might benefit from psychotropic medication (e.g. Campo et al., 2004). Self-Reliant Copers might be most responsive to treatments that emphasize self-management.

This study provides support for the validity of our typology in describing distinct and meaningful patterns of coping used by pediatric patients with CAP. Future research should assess whether the profiles generalize across pediatric pain populations. Prospective studies demonstrating the stability of the profiles over time as well as their relation to outcomes and treatment responses are needed to establish the profiles’ reliability, predictive validity, and clinical utility. Finally, children’s pain coping profiles should be linked to developmental processes, such as attachment and mastery, and to the emergence of chronic pain in adolescence and adulthood.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Sage University paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Beverly Hills; Sage: 1984. Cluster analysis. (Series No. 07-044) [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Warr D. Coping, catastrophizing and chronic pain in breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(3):265–281. doi: 10.1023/a:1023464621554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol I Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 19691997. [Google Scholar]; Bishop SR, Warr D. Coping, catastrophizing and chronic pain in breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(3):265–281. doi: 10.1023/a:1023464621554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Nicassio PM. Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1987;31:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Nicassio PM, Wallston KA. Pain coping strategies and depression in rheumatoid arthritis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(5):652–657. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Kubilus A, Bruehl S, Harden RN. A fourth empirically derived cluster of chronic pain patients based on the multidimensional pain inventory: Evidence for repression within the dysfunctional group. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:663–673. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch B, Walco GA, Zeltzer LK. Clinical assessment of chronic pain and pain-associated disability syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:45–53. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo JV, Perel J, Lucas A, Bridge J, Ehmann M, Kalas C, et al. Citalopram treatment of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain and comorbid internalizing disorders: An exploratory study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1234–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000136563.31709.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol 1. Theory and methods. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 3–0.pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogasch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Claar RL, Walker LS. Functional assessment of pediatric pain patients: Psychometric properties of the Functional Disability Inventory. Pain. 2006;121:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison E, Asenlof P, Sandborgh M, Lindberg P. Musculoskeletal pain in primary health care: Subgroups based on pain intensity, disability, self-efficacy, and fear-avoidance variables. J Pain. 2007;8:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Walker LS, Zeman J. Somatization symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents: Further validation of the Children Somatization Inventory. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:588–595. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. Denver: CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman PE, Bursch B, Sood M, Schwankovsky L, Cocjin J, Zeltzer LK. Visceral pain-associated disability syndrome: A descriptive analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:663–668. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Chronic pain coping measures: Individual vs. composite scores. Pain. 1992;51:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Patterson JM, Wilson LR. Family Inventory of Life Events. In: Olson DH, McCubbin HI, Barnes H, Larsen A, Muxen M, Wilson M, editors. Family inventories. St. Paul: University of Minnesota; 1982. pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams LA, Asmundson GJG. The relationship of adult attachment dimensions to pain-related fear, hypervigilance, and catastrophizing. Pain. 2007;127:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith P, Strong J, Feeney JA. Adult attachment, anxiety, and pain self-efficacy as predictors of pain intensity and disability. Pain. 2006;123:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers CD, Riley JL, Robinson ME. Psychosocial contributions to sex-correlated differences in pain. Cl J Pain. 2003;19:225–232. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Davis D, Keefe FJ. Attachment and pain: Recent findings and future directions. Pain. 2007;128:195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins PM, Smith SM, Glutting JJ, Bishop CT. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:397–408. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M, Shepherd R, Cleghorn G, Woolford H. The treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children: a controlled comparison of cognitive-behavioral family intervention and standard pediatric care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:306–314. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff L, Langan N, Rotter N, Scott-Sutherland J, Schenk C, Taor N, McDonald-Nolan L, Masek B. Psychological, behavioral, and family characteristics of pediatric patients with chronic pain: a 1-year retrospective study and cluster analysis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:432–438. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000130160.40974.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Wallston KA. An analysis of coping profiles and adjustment in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1996;9:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Wallston KA, Dwyer KA. Coping and adjustment to rheumatoid arthritis. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. London: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 458–494. [Google Scholar]

- Snow-Turek AL, Norris MP, Tan G. Active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1996;64(3):455–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Cl J Pain. 2001;17:52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC, Rudy TE. The robustness of an empirically derived taxonomy of chronic pain patients. Pain. 1990;43:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90047-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Garber J. Manual for the Children’s Somatization Inventory. Nashville: TN: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Pediatrics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Greene JW. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: more somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families? J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14(2):231–243. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Greene JW. The Functional Disability Inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, Claar RL. Testing a model of pain appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):364–274. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, Van Slyke DA. Development and validation of the Pain Response Inventory for children. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(4):392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Yong H. Can attitudes of stoicism and cautiousness explain observed age-related variation in levels of self-rated pain, mood disturbance and functional interference in chronic pain patients? Eur J Pain. 2006;10:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]