Abstract

One in seven women who have a baby will experience postpartum depression. Although there are many treatments for postpartum depression, many women do not receive assistance. When left untreated, this condition can have a deleterious affect on the woman’s health/mental health, the child’s cognitive, psychological, emotional and social development, the marital relationship and ability to contribute to society. This study examined 45 women’s self-reported desire for PPD care and ability to obtain these services in Erie County, New York. Results showed differences in desired care by race, differences in access to care by race and revealed the lack of PPD care in general.

Keywords: postpartum depression, race, access to care, women, mental health

Introduction

Depression is projected by the World Health Organization to be one of the three leading causes of mortality by the year 2030 (Mathers & Loncar, 2006). Currently, suicide as a result of postpartum mood disorders is the leading cause of death for women peri- and postpartum in the United States (Lindahl et al, 2005). The most prevalent postpartum mood disorder is depression (PPD) affecting 10%–20% of women (Moses-Kolko & Roth, 2004; O’Hara & Swain, 1996; Stuart et al, 1998). Yet, women’s self-reports have shown up to 55% experiencing moderate to severe PPD (CDC, 2002).

Prevalence rates by ethnicity/race suggest that African-American and Hispanic women experience PPD more frequently than do Caucasian women (Howell et al, 2005). One study found up to 35% of the African-American female population reporting PPD symptoms (Moses-Kolko & Roth, 2004) while another found 38% of Mexican-American participants with PPD (Martinez-Schallmoser et al, 2003). Symptoms begin about two weeks after delivery and include a depressed mood, anxiety, short temper, feeling hopeless, lack of interest in the newborn baby or other activities in general, decreased appetite, lower levels of concentration/focus, feelings of guilt, depressed mood, and sleeplessness (United States Department of Health & Human Services, 2005).

PPD Treatments

Numerous biopsychosocial interventions have been shown to significantly reduce PPD symptoms. The most popular medically-based interventions are antidepressant medication (Marcus et al, 2001), estrogen therapy (Cattel & King, 1996; Gregoire, et al., 1996; Grigoriadis & Kennedy, 2002), home health care (Appleby et al, 2003; Armstrong et al, 1999; Mauthner, 1997; Parke & Hardy, 1997, Simons et al, 2003), inpatient hospitalization (Boulvain et al, 2004), psychiatric day treatment programs (Boath et al, 1999) and educational materials provided at discharge from maternity floors (Ahn & Kim, 2004; Garg et al, 2005).

Several types of counseling strategies have been implemented to improve PPD symptoms for women including short-term/long-term individual counseling (Cooper et al, 2003; Murray et al, 2003), group counseling and support groups. Ideally, psychological treatments for the mother alone, coupled with dyadic treatment of the mother and baby appear to have the best outcomes with PPD symptoms decreasing and improved mother-baby bonding and interaction (Clark et al, 2003; O’Hara, et al, 2000). Counseling programs range from traditional such as cognitive behavioral treatment (Milgrom et al, 2006) to those that incorporate nontraditional interventions such as art and body therapy (Kersting et al, 2003). Group treatments have included therapeutic group counseling (Craig et al, 2005; Klier et al, 2001), psycho-education (Honey et al, 2002), relaxation skills training (Dennis, 2004), partner support groups (Kostaras et al, 2000), general support groups in the community (Chen et al, 2000, Maley, 2002; Martinez-Schallmoser et al, 2003; Olson et al, 1991; Scrandis, 2005).

When untreated, one in four women will continue to suffer with PPD one year after delivery (Gregoire et al, 1996), and one in twenty-one women will have PPD two years after delivery (Lumley et al, 2003). Women with untreated PPD are 300 times more likely to experience it again during subsequent pregnancies (Hamilton & Sichel, 1992) with postpartum suicide during a relapse of mental health symptoms being the highest risk for death than any other medical condition (Bates & Paeglis, 2004). Additionally, not receiving treatment for PPD has short and long-lasting affects on the mother, child and family (Refer to List 1).

List 1.

Risks of Untreated Maternal Depression

| Negative Impact | Results | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Inability to attach to baby | Child abuse/neglect | Civic & Holt, 2000; Scott, 1992 |

| Chronic depression | Minimal responsiveness to child interaction cues | Nonacs et al, 2005 | |

| Exacerbation of mental health symptoms | Suicide, infanticide | Peel, 2001 | |

| Children | Inability to attach to mother | Impaired social, emotional, behavioral and cognitive development | Civic & Holt, 2000; Murray & Cooper, 1997; Nonacs et al, 2005 |

| Prolonged exposure to maternal depression | Mental health difficulties (e.g.: anxiety, substance abuse) | Campbell et al, 1995; Carter et al, 2001; Johnson et al, 2001; NICHD, 1999 | |

| Marital Relationship | Male partner experiences the woman with PPD as overwhelming, isolating, stigmatizing and frustrating | Conflict in the marital relationship | Davey et al, 2006 |

| Society | Limited public understanding of PPD | Blaming and “punishing” the woman (ie: imprisonment, denial of mental health services by HMOs) | Hickman & LeVine, 1992; Peel, 2001 |

Barriers to care

Women tend to not seek out professional treatment for PPD without external prompting (Brown & Lumley, 2000; Chaudron et al, 2005; Lumley et al, 2003; Hearn et al, 1998; Small et al, 1994). One study found that only 2% of women sought psychiatric services for mental health symptoms within the first postpartum year (Kendell et al, 1987) and another found that only one in three sought primary care physician assistance with mental health symptoms (Lumley et al, 2003). The most commonly cited barriers to PPD care can be found in List 2.

List 2.

Common barriers to PPD care

| Barriers | References |

|---|---|

| Professionals’ response to reported symptoms | Wood, & Meigan, 1997 |

| Cultural barriers | Chaudron et al, 2005 |

| Unhelpful/unsupportive comments from professionals | Holopainen, 2002 |

| Limited time for counseling from professionals | Holopainen, 2002 |

| Receiving a prescription for symptoms without discussion of other options or additional support | Holopainen, 2002; Wood, & Meigan, 1997 |

| Professionals neglect to involve family members in PPD treatment | Holopainen, 2002 |

| Lack of child care to attend PPD treatment programs | Ugarriza, 2004 |

| Did not know where to look for assistance/minimal specialists in PPD | Holopainen, 2002; Oates, 2000 |

| Long wait list to get in to see the professional | Wood, & Meigan, 1997 |

It is difficult to find medical, mental health and spiritual counselors who specialize in or who have training in PPD interventions (Oates, 2000). This being the case, professionals tend to avoid talking about PPD because, if detected, the professionals are unclear as to the next steps to take (Gjerdingen, 2003).

The United States is the only Western country that imprisons women who have committed infanticide as a consequence of untreated postpartum psychosis (Hickman & LeVine, 1992). It is argued that many women who experience postpartum psychosis and/or other postpartum mood disorders who commit infanticide could be stopped earlier if there was a better structural system in place to provide assistance

Purpose of this study

An online search of medical and psychological search engines did not locate any research that evaluated preferred PPD treatment from the woman’s perspective or the extent to which the preferred treatment was obtained. This study will examine the connection to desired treatment in women residing in Erie County, New York, as well as any differences across races.

Materials and Methods

Sample and procedures

Survey methods were used in this study and a convenience sample of forty-five women living in Western New York who had or were currently experiencing PPD. Participants for the study were obtained through newspaper advertisements and referrals from local OB/GYNs (Obstetrician and Gynecologist) and a psychiatrist. Newspaper advertisements were posted in major newspapers in Erie County including several that were free to the public. Ads requested for women over age 18 who experienced PPD symptoms (symptoms were described in detail) to contact the research team to participate in the study. The OB/GYNs were made aware of the study via mass mailings and the psychiatrist was a consultant on the grant that funded the project. OB/GYNs were requested to post a study announcement flyer in the office. Information on the flyer was similar to that in the newspaper ads. The psychiatrist verbally referred patients who currently had or have experienced PPD in the past to the project. The majority of study participants were obtained through the newspaper advertisements.

Study participants contacted the research staff by leaving a confidential message on an office answering machine. Research assistants then contacted participants via telephone and reviewed the informed consent, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) policies and inquired if the participant had PPD either currently or in the past. Women were asked if she experienced PPD in the past or currently and the duration of PPD. Women who had PPD and who consented and agreed with the HIPAA policies were interviewed over the telephone. A copy of the informed consent and HIPAA policies were sent to each participant with a gift certificate for a free haircut and color at Fantastic Sam’s, a local chain hair salon, to compensate them for their time. Interviews typically took approximately twenty minutes to complete. At the end of the telephone interview, participants were debriefed to ensure mental health safety. Participants that indicated discomfort or reported a need for a referral for mental health treatment were provided information by the principal investigator. The principal investigator was made aware of the discomfort/need for a referral by the research assistants immediately following the interview. Only two participants requested a mental health counselor referral and one requested a primary care physician referral. No participants indicated to the research assistants during debriefing of any significant distress or discomfort.

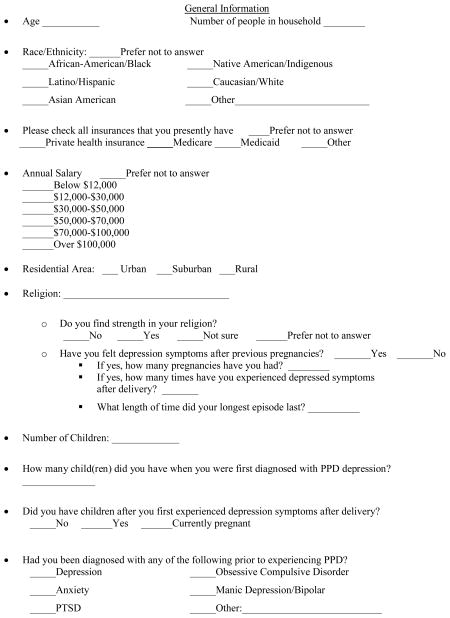

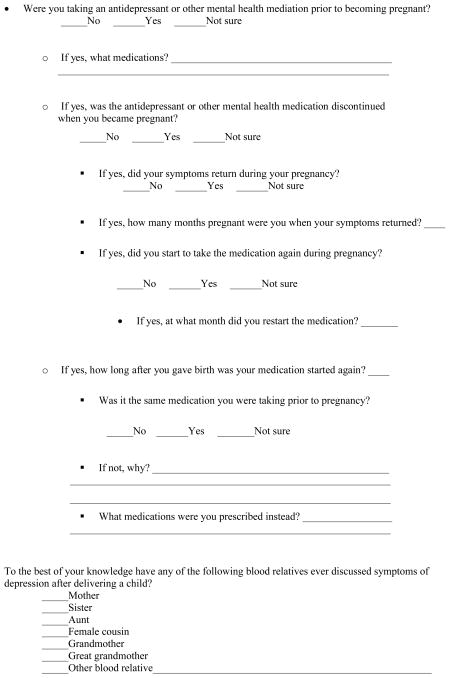

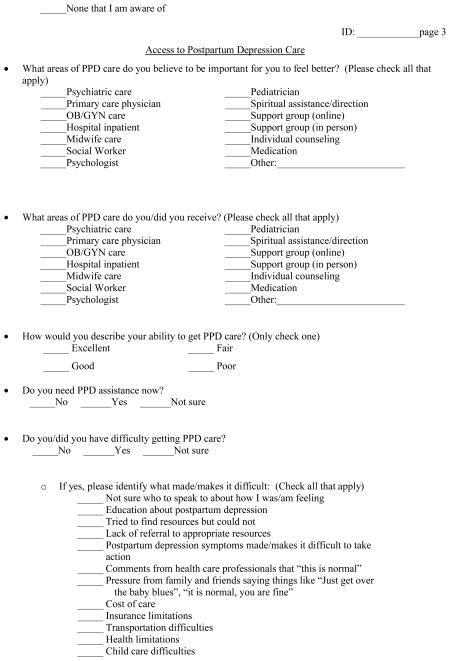

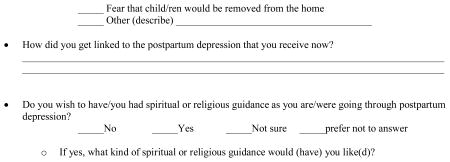

A questionnaire was developed by the principle investigator, psychiatrist and research assistants to assess the biopsychosocial experiences of women with PPD and access to care needs (See Appendix). Questions were based on existing literature and on personal experience working with this population.

The majority of the data collected were categorical or nominal-level data; therefore, examination of the data was limited to nonparametic analyses. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to identify demographics and other individual characteristics of the sample. Pearson’s chi-square analysis was conducted to determine significant differences based on race. As an alternative, a likelihood ratio chi-square analysis was conducted to determine any significant differences not identified using Pearson’s chi-square due to the small sample size. These same analyses were conducted to determine differences between desired care and care actually received across the entire sample and by race.

Results

Sample Demographics

Forty-five women approximately 30 years old (Range=18–48, M=29.8, SD±7.23) were surveyed. Of these, 51.1% (n=23) were Caucasian and 48.9% (n=22) identified as minority. Of those identified as minority, 40.0% were African-American, followed by 4.4% Hispanics, 2.2% Asian-American and 2.2% other (Refer to Table 1), with more than half reported having private insurance and 48.9% received Medicaid benefits. There was a slight overlap with seven (15.6%) participants reporting both private insurance and Medicaid. Nearly half of the sample had an income less than $12,000 annually and most lived in an urban setting.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Group Differences

| Total Sample N=45 | Caucasian n=23 | Minority n=22 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Factors | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | χ2 |

| Ethnicity | 23 (51.1) | 22 (48.9) | 45.000 | |

| African American | 18 (40.0) | -- | 18 (81.8) | -- |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.4) | -- | 2 (9.1) | -- |

| Asian American | 1 (2.2) | -- | 1 (4.5) | -- |

| Other | 1 (2.2) | -- | 1 (4.5) | -- |

| Insurance | 16.927 | |||

| Private | 28 (62.2) | 18 (78.3) | 10 (45.5) | 5.148** |

| Medicaid | 22 (48.9) | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | 9.789** |

| Annual Income (4 missing) | 41.000 | |||

| <$12,000 | 19 (46.3) | 7 (35.0) | 12 (57.1) | 2.02 |

| >$12,000 | 22 (53.7) | 13 (65.0) | 9 (42.9) | 2.02 |

| Residence (2 missing) | 43.000*** | |||

| Urban | 24 (55.8) | 5 (22.7) | 19 (90.5) | 19.996*** |

| Suburban | 19 (44.2) | 17 (77.3) | 2 (9.5) | 19.996*** |

| PPD History/Characteristics | ||||

| Had 0–1 child when first diagnosed | 32 (71.1) | 19 (82.6) | 13 (59.1) | 3.027 |

| Had 2–6 children when first diagnosed | 13 (28.9) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (40.9) | 3.027 |

| Other family members had PPD | 22 (48.9) | 10 (43.5) | 12 (54.5) | .551 |

| Mental health diagnosis prior to PPD | 21 (46.7) | 10 (43.5) | 11 (50.0) | .192 |

| Depression | 17 (81.0) | 8 (34.8) | 9 (40.9) | .180 |

| Anxiety | 11 (52.4) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (27.3) | .186 |

| Taking psychotropic mediation when pregnancy was determined | 12 (26.7) | 8 (34.8) | 4 (18.2) | 1.585 |

| Medication discontinued when pregnancy was determined | 8 (66.7) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (100.0) | 3.000 |

p <.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Approximately half of the women in this study reported a family history of PPD. Approximately, 47% had a mental health diagnosis prior to experiencing PPD; a majority of these women were diagnosed with depression and/or anxiety. Nearly 25% of the women were receiving antidepressant medications at the time of their pregnancy and eight of these discontinued medications when pregnancy was verified. These same eight women experienced the return of mental health symptoms postpartum.

Pearson’s chi-square analysis showed several differences by ethnic group. Less than half of the women who were members of a minority race had private insurance - nearly three in four of these women received Medicaid assistance. The majority of Caucasians lived in suburban settings while their minority counterparts lived in urban areas.

Care received compared to desired care

While the majority of participants valued medical, mental health and spiritual assistance, not all participants received this care. Table 2 displays the areas of care women valued in order of preference compared to the care the women actually received. This information is then further broken down into the percentage of women who actually received valued PPD care.

Table 2.

Valued Care versus Received Care

| Valued care (Total sample n) | Received care (Total sample n) | % who received desired care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Care | n (%) | n (%) | % | χ2 |

| Individual Counseling | 38 (84.4) | 9 (20.0) | 23.7 | .169 |

| OB/GYN | 33 (73.3) | 18 (40.0) | 54.5 | 3.712* |

| Medication | 33 (73.3) | 11 (22.4) | 33.3 | 5.294* |

| In-Person Support Group | 33 (73.3) | 3 (6.7) | 9.1 | 1.169 |

| Psychiatric | 33 (73.3) | 6 (13.3) | 18.2 | .354 |

| Psychologist | 32 (71.1) | 6 (13.3) | 18.8 | 4.456* |

| Primary Care Physician | 32 (71.1) | 14 (31.1) | 43.8 | 4.678* |

| Hospital Inpatient | 31 (68.9) | 4 (8.9) | 12.9 | 1.983 |

| Online Support Group | 30 (66.7) | 3 (6.7) | 10.0 | .000 |

| Social Worker | 30 (66.7) | 3 (6.7) | 10.0 | 1.607 |

| Spiritual Assistance/Direction | 29 (64.4) | 9 (20.0) | 31.0 | .024 |

| Pediatrician (5 missing from N) | 24 (60.0) | 1 (2.5) | 4.2 | .684 |

| Midwife | 26 (57.8) | 6 (13.3) | 23.1 | 1.853 |

p <.05

The most valued professionals to provide PPD care were OB/GYNs, followed by psychiatrists, psychologists, primary care physicians, social workers, pediatricians and midwives. The most valued PPD treatments were identified as individual counseling, medication, in-person support group, hospitalization, online support group, and spiritual assistance/direction. Women reported receiving assistance from the following professionals in descending order: OB/GYNs, primary care physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, midwives, social workers and pediatricians. Most frequently received treatments were medication, spiritual assistance/direction, individual counseling, hospitalization, and in-person and online support groups.

When chi-square analysis was conducted, significant differences in three areas of valued versus desired care were found. A total of 18 women received OB/GYN care with PPD. Of these, 16 (88.9%) identified OB/GYN care as important and only 2 (11.1%) did not. However, of the 33 who indicated that OB/GYN assistance with PPD was important, 17 (51.5%) reported not receiving this assistance (χ2=3.712, p=.054). Thirty-two (71.1%) women valued psychologist services, but only six (18.8%) received this service (Likelihood Ratio=4.46, p=.035). Finally, significant differences were found between those who valued and received medication for PPD symptoms. Out of the 33 women who valued medication, only 11 (33.3%) received this care (χ2=5.29, p=.021).

Race

While the majority of women sampled desired care and generally, most did not receive the desired care, difference in desired and received care were found by race. Caucasians valued professional care from OB/GYNs, social workers, psychologists, primary care physicians, psychiatrists, pediatricians, and midwives (refer to Table 3); whereas minorities valued professional care from psychiatrists, primary care physicians, psychologists, OB/GYNs, social workers, pediatricians and midwives (refer to Table 3).

Table 3.

Valued care compared to received care by race

| Type of Care | Valued Care for Caucasians n (%) | χ2 | Received Care for Caucasians n (%) | χ2 | % That Received Desired Care: Caucasians | Type of Care | Valued Care for Minorities n (%) | χ2 | Received Care for Minorities n (%) | χ2 | % That Received Desired Care: Minorities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Counseling | 20 (87.0) | .226 | 3 (13.0) | 1.423 | 15.0 | Individual Counseling | 18 (81.8) | .226 | 6 (27.3) | 1.423 | 33.3 |

| OB/GYN | 20 (87.0) | 4.465* | 14 (60.9) | 8.538** | 70.0 | Psychiatric | 17 (77.3) | .342 | 3 (13.6) | .003 | 17.6 |

| Medication | 19 (82.6) | 2.070 | 6 (26.1) | .069 | 31.6 | Spiritual Assistance/Direction | 16 (72.7) | 1.289 | 3 (13.6) | 1.089 | 18.8 |

| Social Worker | 18 (78.3) | 2.946 | 2 (8.7) | .311 | 11.1 | Primary Care Physician | 16 (72.7) | .055 | 5 (22.7) | 1.412 | 31.3 |

| In-Person Support Group | 18 (78.3) | .584 | 2 (8.7) | .311 | 11.1 | In-Person Support Group | 15 (68.2) | .584 | 1 (4.5) | .311 | 6.7 |

| Psychologist | 17 (73.9) | .180 | 4 (17.4) | .670 | 23.5 | Psychologist | 15 (68.2) | .180 | 2 (9.1) | .670 | 13.3 |

| Primary Care Physician | 16 (69.6) | .055 | 9 (39.1) | 1.412 | 56.3 | Hospital Inpatient | 15 (68.2) | .010 | 4 (18.2)* | 4.590* | 26.7 |

| Psychiatric | 16 (69.6) | .342 | 3 (13.0) | .003 | 18.8 | Medication | 14 (63.6) | 2.070 | 5 (22.7) | .069 | 35.7 |

| Online Support Group | 16 (69.6) | .178 | 1 (4.3) | .407 | 6.3 | Online Support Group | 14 (63.6) | .178 | 2 (9.1) | .407 | 14.3 |

| Hospital Inpatient | 16 (69.6) | .010 | 0 (0.0) | 4.590* | 0.0 | OB/GYN | 13 (59.1) | 4.465* | 4 (18.2) | 8.538** | 30.8 |

| Pediatrician (5 missing from N) | 13 (68.4) | 2.946 | 1 (5.3) | 3.010 | 7.7 | Social Worker | 12 (54.5) | 2.946 | 1 (4.5) | .311 | 8.3 |

| Midwife | 15 (65.2) | 1.067 | 5 (21.7) | 2.877 | 33.3 | Pediatrician (5 missing from N) | 11 (52.4) | 2.946 | 0 (0.0) | 3.010 | 0.0 |

| Spiritual Assistance/Direction | 13 (56.5) | 1.289 | 6 (26.1) | 1.089 | 46.2 | Midwife | 11(50.0) | 1.067 | 1 (4.5) | 2.877 | 9.1 |

p <.05,

p<.01

Caucasians valued the following PPD treatments in descending order: individual counseling, medication, in-person and online support groups, hospitalization and spiritual assistance/direction. Comparatively, minorities valued individual counseling, spiritual assistance/direction, in-person support group, hospitalization, medication, and online support group PPD treatments.

The most frequently received care by professionals for Caucasians was from OB/GYNs, followed by primary care physicians, midwives, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and pediatricians. On the other hand, the most frequently received care by professionals for minorities was from primary care physicians followed by OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and midwives. None of the minorities in this sample received assistance from a pediatrician. Caucasians reported receiving medication and spiritual assistance/direction most frequently, proceeded by individual counseling, in-person and online support groups. None of the Caucasians in this sample were hospitalized for PPD symptoms. Minorities most frequently received individual counseling treatment. This was followed by medication, hospitalization, spiritual assistance/direction, and online and in-person support groups.

Approximately, two in three Caucasians received OB/GYN care compared to less than one in five women in minority groups (χ2=8.538). Alarmingly, however, nearly 20% of women in minority groups were hospitalized for PPD compared to zero Caucasians (χ2=4.590).

Access to PPD care

Despite differences between desired care and actual care received, just over half (n=25, 55.6%) of the women in this study indicated her access to PPD care was good to excellent. When participants were asked what impeded access to PPD care, seven (15.6%) reported not being sure who to speak to and the same number tried to find resources, but were unable to locate assistance. Six (13.3%) responded that she had a need for each of the following areas: lack of PPD education, PPD symptoms made it difficult to take action, pressure from family and friends did not help, and comments from health care professionals prevented access to PPD care. Although only 26.7% (n=12) of the women reported needing PPD care at the time of the interview, the majority of these women were minorities. Nearly half (45.5%, n=10) of women who were in a minority group reported currently needing PPD assistance, compared to only 2 (9.1%) Caucasian women.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study looked at the self-reported preferred treatment for PPD compared to actually obtaining the desired care. Women indicated that all forms of assistance were valued, but few received the care they desired. As a result, half of those sampled reported difficulty assessing care with a quarter needing care at the time of the interview. These women described similar barriers to care as reported in the other studies focusing on PPD.

Women in this sample reported receiving OB/GYN assistance for PPD most frequently compared to other professional assistance. Yet, six in ten women did not receive PPD care from her OB/GYN. Differences between desired care and received care may point to an underlying confusion among professionals and women with PPD: is PPD a medical concern?, mental health concern?, combined concerns?, and what professions should be the primary portal of entry for women with PPD?

Considering medical professionals, it is unclear if care should be provided by (1) OB/GYNs who primarily focus on postpartum health and physical recovery of the women (2) primary care physicians who see women postpartum infrequently (3) pediatricians who primarily focus on the physical development of the child, but who see the mother and child most frequently postpartum or (4) psychiatrists who specialize in the medical and mental health management of depression and PPD, but who typically see women who are already being seen by a psychiatrist. The fragmentation of medical care makes the transition from desired care to actual care received complicated. Add to this complication the uncertainty of women about her symptoms, fear to discuss symptoms, and difficulty finding appropriate referral resources in the community to provide hands on PPD assistance results in further alienation.

Considering the mental health and ancillary support professionals, only one in seven women were able to access desired care from a psychologist, yet approximately 75% wanted this assistance. Although other differences were not statistically significant, it is notable that nearly two in three women wanted social work care, but only one in fifteen actually received it. Again, these differences in desired care versus care actually received may reflect the fragmentation of the system as well as uncertainty about PPD specialists to refer women to.

Interestingly, the one in five women received spiritual assistance or direction with two in three women wanting this assistance. This difference in received care may be due to the perception of spiritual direction as connected to family support. Additionally, psychosocial aspects that contributed to PPD included difficulty finding assistance in the community and difficulty finding support from significant others, friends and family members. Instead, these women found support through religious leaders. However, how many of these leaders are trained to work with PPD, particularly given the traditional perception of female roles in many religions?

Supportive barriers to care included pressure from family and friends, unaccommodating comments from health care professionals, and difficulty motivating themselves to seek assistance due to their PPD symptoms. Not only were the women having difficulty finding the motivation locate help, but once the women did try to seek help, her efforts are not reinforced by professionals or by significant others in her life.

Care preference compared to care received

Results of this study found significant overall differences between preferred care and actual care received for OB/GYN, medication and psychologist services. The most frequently desired care was individual counseling with the most care received being OB/GYN. Even though pediatricians are often the most frequented medical professionals following birth for child well visits, it was the least received care in this sample. There are several studies that have shown the efficacy of screening for PPD during child well visits (Chaudron et al, 2004; Currie & Rademacher, 2004; Seidman, 1998). Some reasons for this may be limited PPD education, underestimating the prevalence of PPD, underestimating the potential prevalence of PPD in one’s pediatric practice, and lack of knowledge about PPD assessment instruments (Wiley et al, 2004). Despite the reasons why pediatricians are not providing PPD assistance to mothers, PPD places children at higher risk for abuse/neglect (Scott, 1992), and developmental stagnation/difficulties such as language delay and other cognitive deficits (Murray et al, 1999). As the most frequented medical professionals by women postpartum it is particularly prudent for pediatricians to screen and intervene when appropriate.

Differences in women’s PPD by race

Caucasians in this sample predominantly lived in suburban areas whereas minorities lived in urban areas. While minorities more frequently made below $12,000 annually than Caucasians, they also used Medicaid services more often. Both races primarilty had zero to one child when first diagnosed with PPD, but more minorities had two or more children when diagnosed than did Caucasians. Also, while both races showed evidence of taking medication when pregnancy was determined, minorities were more often prescribed medications and had medication discontinued more frequently.

Caucasians significantly valued OB/GYN care more than minorities. Although not significant, Caucasians valued other services more than minorities including medication, social workers, in-person and online support groups, psychologists and midwifes. This may suggest that Caucasians expect more services to be available for care. This expectation may lead directly to the care that is actually received as psychologists, primary care physicians, midwives, and spiritual support was more frequently received by Caucasians than by minorities. Additionally, OB/GYN care received was significantly different, with Caucasians receiving this care more often.

Minorities received more individual counseling and hospital inpatient treatment. It is noteworthy that four minorities were hospitalized for PPD symptoms whereas no Caucasians received inpatient treatment and more minorities reporting needing PPD assistance during the survey. Caution should be taken when considering this result, however, as severity of PPD symptoms are lacking in this study. Although minorities valued psychiatric care and spiritual support more than did Caucasians, these perceptions of valued care, such as psychiatric, may have been influenced by the predominant use of public assistance and living under the poverty level. Further, it is not surprising that this population of minorities valued spiritual assistance more than Caucasians as the “church” has a prime role in the urban minority community. Strength in religion and spirituality is a common resource for this population as well. Despite this value, however, more Caucasians received spiritual assistance than did minorities. These findings could be reflective of some evidence that some minorities (e,g,: Black Caribbean women in the United Kingdom) reject postpartum mental health symptoms and resort to resilience and empowerment to maximize psychological well-being in a society where being “strong” in the midst of adversity is a way to manage racism (Edge & Rogers, 2005).

Not only is there a clear need for improved access to care for women experiencing PPD, but there is evidence that available PPD care is not equally reachable by all. Women who are minorities, impoverished, and living in urban areas have more difficulty getting the care that is preferred as well as the care that is needed. More attention needs to be given to the services women experiencing PPD need and to the services that are available in order to proactively address this globally emerging mental health care issue. Medical, midwives, and mental health professionals’ education needs to include training in assessment and treatment of PPD. In addition, greater awareness of the symptoms and challenges associated with PPD are needed to inform and educate the general public, women, and families. As well, residual and preventive programs need to be made available in the community such as encouraging supportive partners, respite programs, and mother-infant dyad groups.

Study Limitations

Due to the participant recruitment procedures employed by this project, generalizability of study results may be limited. Further, this study was conducted in the United States, further limiting generalizability to women living in other countries. Limitations to reliability are also posed due to the inability to prove other than by verbal report that women indeed had experienced PPD. Some responses indicate the experience of postpartum blues rather than full blown PPD, yet the women reported having PPD.

Additionally, the severity of PPD symptoms was unable to be discussed in relation to study findings. Although participants were administered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey to determine the severity of PPD, results were not reported here due to an inability to determine if women were reporting current or past severity of symptoms. Along these lines, according to the ways in which participants responded it appears that some were pregnant when reporting PPD symptoms. Therefore, study results need to take into account that some participant may have been experiencing perinatal depression rather than postpartum depression.

Acknowledgments

Special appreciation is given to Fantastic Sam’s for donating gift certificates to study participants. This project was support by the Buffalo State College Research Foundation.

Appendix A

Contributor Information

Kimberley Zittel-Palamara, Social Work Department, Buffalo State College.

Julie R. Rockmaker, Boys and Girls Club.

Kara M. Schwabel, Director, Creativision, www.creativisioning.com.

Wendy L. Weinstein, Psychiatry Department, Buffalo Medical Group.

Sanna J. Thompson, School of Social Work, University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Ahn YM, Kim MR. The effects of a home-visiting discharge education on maternal self-esteem, maternal attachment, postpartum depression and family function in the mothers of NICU infants. Daehan Ganho Haghoeji. 2004;34(8):1468–1476. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2004.34.8.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby L, Hirst E, Marshall S, Keeling F, Brind J, Butterworth T, Lole J. The treatment of postnatal depression by health visitors: Impact of brief training on skills and clinical practice. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;77(3):261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong KL, Fraser JA, Dadds MR, Morris J. A randomized, controlled trial of nurse home visiting to vulnerable families with newborns. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health. 1999;35(3):237–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates C, Paeglis C. Motherhood and mental illness. RCM Midwives. 2004;7(7):286–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boath E, Cox J, Lewis M, Jones P, Pryce A. When the cradle falls: The treatment of postnatal depression in a psychiatric day hospital compared with routine primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;53(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulvain M, Perneger TV, Othenin-Girard V, Petrou S, Berner M, Irion O. Home-based versus hospital-based postnatal care: A randomized trial. BJOG: International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2004;111(8):807–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Lumley J. Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(10):1194–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF, Meyers T. Depression in first-time mothers: Mother-infant interaction and depression chronicity. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:340–357. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Garritty-Roukas FE, Chazan-Cohen R, Little C, Briggs-Gowan M. Maternal depression and co-morbidity: Predicting early parenting, attachment security and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): PRAMS and postpartum depression. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/References/PPD.htm. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HI, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Kitzman HJ, Peifer KL, Morrow S, Perez LM, Newman MC. Self-recognition of and provider response to maternal depressive symptoms in low-income Hispanic women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2005;14(4):331–338. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Tseng YF, Chou FH, Wang SY. Effects of support group intervention in postnatally distressed women: A controlled study in Taiwan. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49(6):395–399. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civic D, Holt VL. Maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in a nationally representative normal birthweight sample. Marternal Child Health Journal. 2000;4:215–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1026667720478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Tluczek A, Wenzel A. Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A preliminary report. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73(4):441–454. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: I. Impact on maternal mood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E, Judd F, Hodgins G. Therapeutic group programme for women with postnatal depression in rural Victoria: A pilot study. Australasian Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):291–295. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie ML, Rademacher R. The pediatrician’s role in recognizing and intervening in postpartum depression. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2004;51(3):785–801. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey SJ, Dziurawiec SS, O’Brien-Malone A. Men’s voices: Postnatal depression from the perspective of male partners. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16(2):206–220. doi: 10.1177/1049732305281950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL. Treatment of postpartum depression, Part 2: A critical review of non-biological interventions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(9):1252–1265. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge D, Rogers A. Dealing with it: Black Caribbean women’s response to adversity and psychological distress associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and early motherhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Morton S, Heneghan A. A hospital survey of postpartum depression education at the time of delivery. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(5):587–594. doi: 10.1177/0884217505280005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen D. The effectiveness of various postpartum depression treatments and the impact of antidepressant drugs on nursing infants. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2003;16(5):372–382. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, et al. Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet. 1996;347:930–933. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis S, Kennedy SH. Role of estrogen in the treatment of depression. Journal of Therapeutics. 2002;9(6):503–509. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JA, Sichel DA. Postpartum measures. In: Hamilton JA, Harberger PN, editors. Postpartum psychiatric illness: A picture puzzle. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1992. pp. 219–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn G, Iliff A, Jones I, Kirby A, Ormiston P, Parr P, Rout J, Wardman L. Postnatal depression in the community. The British Journal of General Practice; The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1998;48(428):1064–1066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SA, LeVine DL. Postpartum disorders and the law. In: Hamilton JA, Harberger PN, editors. Postpartum psychiatric illness: A picture puzzle. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1992. pp. 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen D. The experience of seeking help for postnatal depression. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;19(3):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey KL, Bennett P, Morgan M. A brief psycho-educational group intervention for postnatal depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41(Pt 4):405–409. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H. Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;105(6):1442–145. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164050.34126.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Cohen P, Kasen S, Smailes E, Brook J. Association of maladaptive parental behaviour with psychiatric disorder among parents and their offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;58:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:662–673. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A, Kuschel S, Reutemann M, Ohrmann P, Arolt V. Outpatient psychotherapy for mothers: First empirical results. Psychiatry. 2003;66(4):335–345. doi: 10.1521/psyc.66.4.335.25442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier CM, Muzik M, Rosenblum KL, Lenz G. Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for the group setting in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice & Research. 2001;10(2):124–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostaras X, Fox D, Kostaras D, Misri S. The impact of partner support in the treatment of postpartum depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;45(6):554–558. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J, Small R, Brown S, Watson L, Gunn J, Mitchell C, Dawson W. PRISM (Program of Resources, Information, and Support for Mothers): Protocol for a community-randomised trial. BMC Public Health. 2003;3(36) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley B. Creating a postpartum depression support group: Out of the blue. AWHONN Lifelines. 2002;6 (1):62–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.2002.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SM, Barry KL, Flynn HA, Tandon R, Greden JF. Treatment guidelines for depression in pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2001;72:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Schallmoser L, Telleen S, MacMullen NJ. The effect of social support and acculturation on postpartum depression in Mexican American women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14(4):329–338. doi: 10.1177/1043659603257162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers DC, Loncar D. Projections of global morality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.137/journal.pmed.0030442. http://medicine.plosjournals.org/archive/1549-1676/3/11/pdf/10.1371_journal.pmed.0030442-L.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mauthner NS. Postnatal depression: How can midwives help? Midwifery. 1997;13(4):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(97)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Negri LM, Gemmill AW, McNeil M, Martin PR. A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44(Pt 4):529–542. doi: 10.1348/014466505X34200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses-Kolko EL, Roth EK. Antepartum and postpartum depression: Healthy mom, healthy baby. Journal of the American Medical Womens Association. 2004;59(3):181–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ. Postpartum depression and child development. Psychology Medicine. 1997;27:253–260. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Sinclair D, Cooper P, et al. The socioemotional development of 5-year old children of postnatally depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:1259–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trail of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: II. Impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (NICHD) Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonacs RM, Soares CN, Viguera N, Pearson K, Poitras JR, Cohen LS. Bupropion SR for the treatment of postpartum depression: A pilot study. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;8(3):445–449. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal maternal mental health services. London, England: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1039–1045. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risks of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Olson MR, Cutler LA, Legault F. Bittersweet: A postpartum depression support group. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1991;82(2):135–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke S, Hardy B. Postnatal depression: Making better use of health visitors and community psychiatric nurses. Professional Care of Mother & Child. 1997;7(6):151–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel D. Infanticide happens when no real mental health care exists. Texas Medicine. 2001;97(9):15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. Early identification of maternal depression as a strategy in the prevention of child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:345–358. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90044-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrandis DA. Normalizing postpartum depressive symptoms with social support. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2005;11(4):223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman D. Postpartum psychiatric illness: The role of the pediatrician. Pediatrics in Review. 1998;19(4):128–131. doi: 10.1542/pir.19-4-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small R, Brown S, Lumley J, Astbury J. Missing voices: What women say and do about depression after childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1994;12:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, et al. Postpartum anxiety and depression: Onset and co-morbidity in a community sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1998;186:420–424. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugarriza DN. Group therapy and its barriers for women suffering from postpartum depression. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2004;18(2):39–48. doi: 10.1053/j.apnu.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health & Human Services. Depression during and after pregnancy. 2005 http://www.womenshealth.gov/faq/postpartum.htm. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Wiley CC, Burke GS, Gill PA, Law NE. Pediatricians’ views of postpartum depression: A self-administered survey. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2004;7(4):231–236. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AF, Meigan M. The downward spiral of postpartum depression. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 1997;22(6):308–316. doi: 10.1097/00005721-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]