Summary

For two decades, the cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III procedure was the gold standard for the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF), and proved to be effective at eliminating AF. The incidence of late stroke was also very low. However, this procedure was not widely adopted due to its complexity and technical difficulty. Over the last 5-10 years, the introduction of new ablation technology has led to the development of the Cox-Maze IV procedure, as well as, more limited lesion sets, with the ultimate goal of performing a minimally-invasive lesion set on the beating heart, without the need for cardiopulmonary bypass. This review summarizes the current state of the art and future directions in the stand-alone surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. The hope is that as more is learned about the mechanisms of AF and with better preoperative diagnostic technologies capable of precisely locating the areas responsible for AF, it will become possible to tailor specific lesion sets and ablation modalities to individual patients, making the surgical treatment of AF available to a larger population of patients.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ablation, Cox-maze procedure

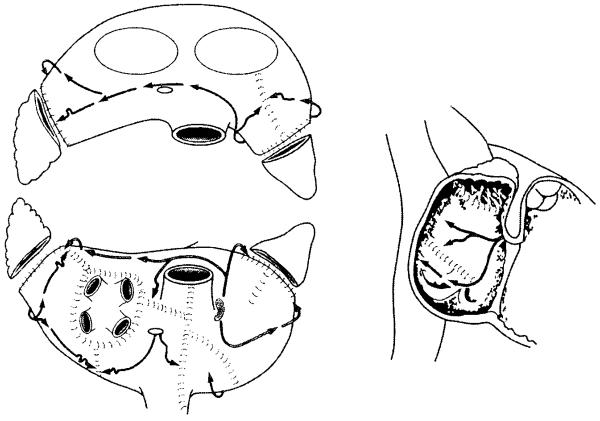

In 1987, Dr. James Cox introduced the first successful surgical treatment for AF at Washington University in St. Louis.1-3 Now known as the Cox-Maze procedure, the operation involved creating a myriad of incisions in both the left and right atria that would direct the propagation of the sinus impulse through both atria while interrupting the multiple macroreentrant circuits thought to be responsible for AF (Figure 1). Improvements and simplifications culminated in the Cox-Maze III procedure, which became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF. Also known as the “cut and sew” Maze, it successfully restored sinus rhythm and atrioventricular synchrony, significantly decreasing the risks of hemodynamic compromise and thromboembolism.4 Between 1988 and 2001, 112 consecutive patients with AF underwent a stand-alone Cox-Maze III procedure at Washington University. Late follow-up was available on 88% of these patients at a mean follow-up of 5.4 ± 3.0 years, and 96% of these patients were free of symptomatic atrial fibrillation, with only one late stroke.5,6 Of the patients who were available for follow-up at 14 years, 92% were free from symptomatic AF, and 80% were off all antiarrhythmic drugs.6 Similar results have been reproduced by other institutions around the world.7-11

Figure 1.

The traditional cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III procedure. (Reprinted with permission from Cox, et al.15)

Ablation technology for faster, less invasive procedures

Despite its proven efficacy, the Cox-Maze III procedure did not gain widespread acceptance due to its complexity and technical difficulty. In order to simplify the procedure, groups have replaced the incisions of the Cox-Maze III with linear lines of ablation.12-14 Over the last decade, the introduction of new ablation technologies utilizing radiofrequency energy, microwave, cryoablation, laser, and high-frequency ultrasound (HIFU) have been used as alternatives to the “cut-and-sew” technique for the surgical treatment of AF. These new technologies have also supported efforts to develop more limited lesion sets that can be performed less invasively, often through small incisions or ports. The ultimate goal has been to perform a curative lesion set epicardially on the beating heart, without the need for cardiopulmonary bypass.

An optimal ablation device for AF surgery would 1) reliably create conduction block (i.e., transmural lesions) on the beating heart from either the endocardial or epicardial surface; 2) exhibit a precise dose-response curve; 3) create lesions rapidly and safely; 4) have adequate flexibility and maneuverability; 5) be adaptable to a minimally-invasive approach. To date, each of the ablation technologies exhibits different advantages and disadvantages and none has fulfilled all of these criteria.

The principal shortcoming of many of these energy sources has been that they are unable to create reliable transmural lesions on the beating heart. Experimental data has shown that unipolar radiofrequency, cryoablation, microwave energy, and laser energy have not been able to overcome this problem.13-15 This has been felt to be due to the heat-sink effect of the circulating intracardiac blood. Our group has shown that lesion depth on the beating heart is dependent on cardiac output, with reliable transmural lesions occurring only at very low cardiac outputs (< 1L/min). 16

There have been two strategies used to overcome this problem. The first has been to use a focused energy source, such as high frequency ultrasound (HIFU). 17,18 While most other ablation technologies rely on thermal conduction to heat or cool the tissue, HIFU directly heats the tissue in the acoustic focal volume, making it much less susceptible to the heat-sink of circulating intracardiac blood. While there has been industry data that suggests HIFU is effective on the beating heart, there have been no confirmatory experimental studies from independent laboratories. Although HIFU is effective at generating temperatures needed for full-thickness, circumferential ablation through rapid direct mechanical heating, it has a fixed depth of penetration, which may be problematic due to the pathologic variability in atrial wall thickness. Also, a recent study has reported that gradual heating of surrounding tissue due to conduction can cause phrenic nerve injury when located within 4-7mm of the focused ablation.19

The other strategy has been to use bipolar radiofrequency energy. The heat-sink is overcome by embedding electrodes into the jaws of a clamp. The target tissue is then clamped and the energy is driven between the closely approximated electrodes. By clamping the tissue, the circulating blood is excluded and has no effect on ablation. Moreover, by monitoring changes in conductance between the electrodes during ablation, it has been possible to predict lesion transmurality. The ability of these devices to create reliable transmural lesions on the beating heart has been confirmed by our laboratory and others in chronic animal models.20-22

Using these new ablation technologies, there have been new surgical procedures developed to treat AF. In the published literature, there have been two broad approaches. The first has been to replicate the entire Cox-maze procedure. An alternate strategy has been to perform pulmonary vein isolation with or without ablation of the ganglionated plexi. These techniques will be reviewed below. In this review, only surgically-treated patients with atrial fibrillation and without concomitant cardiac disease were included. Moreover, in this surgical series, patients over the age of 60 years-old and with hypertension were included as lone AF.

The Cox-Maze IV procedure

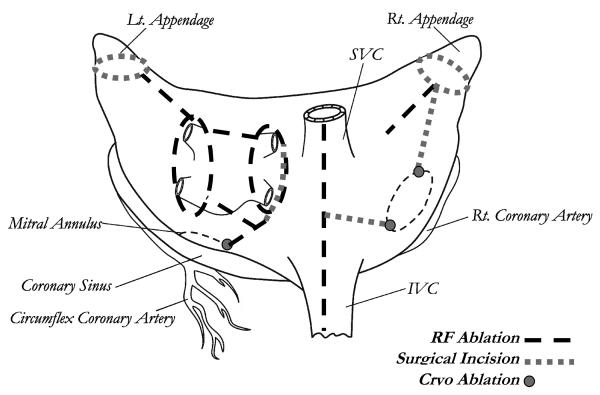

This procedure, introduced by our group, uses bipolar radiofrequency ablation to replace most of the surgical incisions of the Cox-Maze III.23 Bipolar RF was chosen over other potential energy sources due to its ability to create reliable transmural lesions on the beating heart (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Cox-Maze IV lesion set. IVC, inferior vena cava; RF, radiofrequency; SVC, superior vena cava. (Reprinted with permission from Voeller, et al. 82)

As of November 2008, the Cox-Maze IV procedure has been performed on 84 patients with lone AF (unpublished data). Of these patients, 36% had a history of previous catheter ablation. The mean aortic cross-clamp time for a lone Cox-Maze IV procedure was significantly shorter than that for the lone Cox-Maze III (41±12 min vs. 93±34 min, p<0.001), and the freedom from AF recurrence was 91% at 12 months and 67% of patients off antiarrhythmics drugs. A recent propensity analysis of matched patients undergoing the Cox-Maze III versus Cox-Maze-IV at our institution showed that there was no significant difference between these two procedures in terms of the rates of freedom from AF at 3, 6, and 12 months.24 Thus, the Cox-Maze IV has significantly shortened operative times while maintaining the efficacy of the traditional cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III. While this procedure can be performed through a small right thoracotomy, it does still require cardiopulmonary bypass. It has the advantage of having similar success rates in all patients, independent of the type of AF or the underlying pathology. 25

Pulmonary vein isolation

The development of new ablation technologies and the discovery that AF can be triggered from focal sources has led many groups around the world to explore less-invasive, more limited lesion sets. Much emphasis has been placed on stand-alone isolation of the pulmonary veins, as these have the capability to trigger AF in many patients with paroxysmal AF.26-28 Additionally, pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) can be performed epicardially without cardiopulmonary bypass, making it adaptable to minimally-invasive approaches. However, electrophysiologic mapping studies have shown that the triggers for initiating AF are not always in the pulmonary veins,26 and that other regions of the atria can initiate AF.26,29 In order to guarantee that PVI alone will completely eliminate AF in an individual patient, the pulmonary veins must be identified as the focus responsible for the initiation of AF. Unfortunately, current preoperative diagnostic technologies are not capable of precisely locating these triggers of AF, although the active research in this area shows promise.

Recent studies have begun to clarify the role of PVI in the treatment of lone AF. The first series of PVI for AF was reported by Dr. Wolf and colleagues in 2005.30 They performed bilateral video-assisted thoracoscopic PVI, using a bipolar radiofrequency device, and left atrial appendage excision on 27 patients with AF. The procedure was performed through two 10-mm ports and one non-rib spreading 5-cm working port. The results were good with 91% of patients free from AF at 3-month follow-up. 30 Although the study sample was small and follow-up limited, further work has verified the good results of PVI in selected patients with paroxysmal AF.31-34 In a series of minimally-invasive PVI (with targeted partial autonomic denervation) for AF, Edgerton et al. reported that at 6-months' follow-up, 84% of patients (n=43) with paroxysmal AF were in normal sinus rhythm as evaluated by Holter monitor, pacemaker interrogation, and/or event monitor. 31 McClelland and colleagues performed bipolar radiofrequency PVI (with ganglionated plexus ablation) in 11 paroxysmal AF patients, and reported that 91% of them were free of AF one year after surgery, by 30-day continuous monitoring.32 Unfortunately, the results with PVI have been disappointing in patients with persistent or longstanding AF. In their initial report, Edgerton and colleagues reported a freedom from AF, off drugs of only 39% at 6 months in 18 patients. 35 In McClelland's series, only 25% of patients with longstanding AF had a successful procedure. 32

Our results at Washington University have been similar. In 43 patients, our success rate with lone paroxysmal AF has been 80% at 6 months, but was only 38% in patients with persistent, longstanding AF (unpublished data). The poor success rate of PVI has led some groups to propose a more extended lesion set on the beating heart, using new technology developed for this purpose.36 Surgeons should be careful about adopting these experimental procedures. Both acute and chronic studies from our laboratory have shown that recent devices are not capable of creating reliable transmural lesions, particularly on thick atrial tissue when used on the beating heart. 37

Ganglion ablation

Experimentation with less invasive procedures has been based on research on the mechanisms responsible for AF. Electrophysiologic studies have found that local autonomic ganglia (ganglionated plexi, GP) clustered in the epicardial fat pads play a critical role in the initiation and maintenance of AF.38-40 These plexi innervate pulmonary vein myocardial sleeves and adjacent atrial muscle. Local cardiac denervation by radiofrequency application to the pulmonary vein-atrial junctions can prevent inducibility of AF.41 In 2004, Platt et al. reported a study of GP ablation at the bases of the pulmonary veins in 26 patients.41 While follow-up was short (median = 6 months), 84% of patients were free of AF. Similarly, in 2005 Scherlag and colleagues performed left atrial GP ablations coupled with PVI on 33 patients.38 The AF cure rate was 91%, also based on variable follow-up times ranging from 1 to 12 months (median = 5 months). Edgerton and colleagues used bipolar radiofrequency to perform surgical ganglion ablation (coupled with PVI) in 74 patients with lone AF.32 The complete procedure involved bilateral PVI and targeted partial autonomic denervation of the left atrium with selective left atrial appendectomy. At 6-months' follow-up with various methods of AF recurrence detection (ECG, holter, PM interrogation, event monitor), 84% of patients in the paroxysmal-AF group and 57% in the persistent-AF group were in normal sinus rhythm (NSR). Without antiarrhythmic drugs, the NSR rates were 70%, and 35% for the two groups, respectively.

However, the long-term efficacy of ganglion ablation has been questioned.42 A canine study using RF ablation reported that AF inducibility was eliminated immediately after GP ablation, but this denervation effect was reversed within 4 weeks after the ablation.43 Our laboratory has recently confirmed that after surgical ganglion ablation, there is evidence of reinnervation at four weeks.44 More recently, Katritsis et al. used left atrial FP ablation to treat 19 patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF, of which 14 (74%) experienced AF recurrence during the one-year follow-up period.45 Further studies on the long-term effects of ganglion ablation will be necessary before any conclusions about its efficacy can be made. At present, our group does not perform GP ablation on any surgical patients. In our opinion, its' use should be reserved only for centers participating in clinical trials.

Current indications for surgical treatment of lone AF

Based on the HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of AF,46 stand-alone AF surgery should be considered for symptomatic AF patients who prefer a surgical approach, have failed one or more attempts at catheter ablation, or are not candidates for catheter ablation. The referral of patients for surgery with symptomatic, medically-refractory AF in lieu of catheter ablation remains controversial, as there have been no head-to-head comparisons of the outcomes of catheter and surgical ablation of AF. Therefore, the decision, in these instances, needs to be based on each institution's experience with catheter and surgical ablation, the relative outcomes and risks of each in the individual patient, and patient preference.46

There are certain symptomatic patients who may benefit from a surgical over a catheter-based approach. The first group is patients who have developed a contraindication to warfarin. By removing the left atrial appendage and eliminating AF in the great majority of patients, the stroke rate after the Cox-Maze procedure has been low.4 At late follow-up, 88% of patients with lone AF treated with a Cox-Maze procedure at our institution have been able to discontinue their anticoagulation. 4 Another group, which often are referred for surgery, are patients with a left atrial thrombus, which is a contraindication to catheter-based ablation. Relative indications for surgery also include large left atria (greater than 5 cm) and the presence of a mitral valve prosthesis. However, the lack of prospective, randomized studies in these patient populations have prevented the development of definitive guidelines for referral.

In the subset of patients undergoing surgical lone AF ablation, the cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III and less invasive Cox-Maze IV procedures have proved to be effective at eliminating AF and have had a low incidence of stroke.3,47 This procedure has been equally effective for both paroxysmal and persistent AF. Other procedures such as PVI alone are still under investigation and so far, have shown efficacy only in patients with paroxysmal AF. Success rates in patients with longstanding AF have, to date, been disappointing. However, the movement toward simpler, less invasive procedures capable of retaining the efficacy of the full Cox-Maze procedure will undoubtedly expand the indications for lone AF surgery.

Future directions in lone AF surgery

Ideally, surgeons would like to develop a simple, minimally-invasive operation that will not require cardiopulmonary bypass. The procedure should preserve normal atrial physiology, and have minimal to no morbidity and a cure rate above 90%, making it competitive with catheter ablation. Achieving this goal will require significant progress in three major areas: 1) understanding the mechanism of AF in individual patients, 2) redesigning our surgical approach based on these mechanisms and a better understanding of the effect of surgical ablation on atrial electrophysiology, and 3) a better definition of the effect of surgical ablation technology on atrial hemodynamics and function.

It is now known that there are multiple different possible mechanisms of AF,29,48-51 and that this complex arrhythmia can be confidently described only by multipoint mapping. Epicardial activation sequence mapping has been the traditional gold standard for mapping of AF,2 but is both invasive (usually requiring a median sternotomy) and time-consuming, not allowing for real-time analysis in most instances. A newer noninvasive technique, electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI),52-54 offers a potentially useful way to describe the atrial activation sequence and derive mechanistic information from conscious patients prior to surgery. In this new technique, body surface electrograms are recorded from 250 sites. An inverse solution can be calculated by using anatomic information obtained by a computed tomographic (CT) scan made at the time of the recording, and electrograms can be reconstructed on the atrial epicardial surface. This technique has been shown to work well for normal sinus rhythm and atrial flutter.15 Currently our group is testing the technique in patients with persistent AF, in collaboration with Dr. Yoram Rudy at Washington University, the developer of ECGI. The initial results are promising. 15,55 The resulting information can be analyzed to determine activation sequence and frequency maps for individual patients. A strategy for designing patient-specific optimal lesion sets based on ECGI data is being developed based on their atrial geometry, conduction velocity, and refractory period. 56 Initial lesions will be determined by a calculation of the critical area needed to maintain AF in the individual patient 56-58 using mechanistic information derived from activation data and anatomic data from the CT scan.

When the mechanism cannot be defined, the goal will be to create a lesion pattern that will make the atria unable to fibrillate. In this sense, the Cox-Maze III and IV procedures have failed to achieve this goal, with the higher failure rates particularly seen in patients with increasing left atrial size.59,60 or longstanding AF. A recent study performed by our laboratory on a canine model found that the probability of maintaining AF is correlated with increasing atrial tissue areas, widths, and weights, as well as, the length of the effective refractory period and the conduction velocity of the tissue.56 These data may allow surgeons to design custom operations for each patient based on the mechanism of their arrhythmia and their specific atrial anatomy or electrophysiology.

Conclusion

The first Maze procedure was performed in 1987, demonstrating the feasibility of a non-pharmacological treatment for atrial fibrillation. A series of improvements culminated in the Cox-Maze III procedure, which remained the gold standard for almost two decades. Since then, the development of ablation technologies has dramatically changed the field of AF surgery. The replacement of the surgical incisions with linear lines of ablation has transformed a complex, technically demanding procedure into one accessible to the majority of surgeons. More importantly, these new ablation technologies have introduced the possibility of minimally-invasive surgery for AF, prompting numerous efforts to develop simpler procedures that can be performed epicardially, on the beating heart. There is already strong evidence that PVI may be effective in a subset of patients with paroxysmal AF. With extended lesion sets, it may be possible to extend the efficacy of minimally-invasive procedures to patients with persistent and longstanding AF. However, surgeons must remember that the Cox-Maze procedure has good efficacy in these patients and can be performed using a small thoracotomy with acceptable success and low morbidity. 25 Surgeons need to be careful in employing experimental procedures without careful informed consent. It is also imperative for surgeons trying new procedures to carefully follow their results and to publish them in peer-reviewed journals. For surgeons performing AF ablation, it is mandatory to adhere to the recently published guidelines for follow-up of patients and for determining success or failure following these procedures. As we learn more about the mechanisms of AF and develop improved preoperative diagnostic technologies capable of precisely locating the areas responsible for AF, it will become possible to tailor specific lesion sets and ablation modalities to individual patients, making the surgical treatment of lone AF more effective and available to a larger population of patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Training Grant 2T35HL007815-11A1 and NIH Grants R01 HL032257 and R01 HL085113

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Damiano is a consultant for AtriCure, Inc., Medtronic, Inc., and ATS.

References

- 1.Cox JL. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. IV. Surgical technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(4):584–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II. Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the elcctrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(3):406–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox JL, Ad N, Palazzo T. Impact of the Maze procedure on the stroke rate in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118(5):833–840. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, et al. The Cox maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1822–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)01287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damiano RJ, Jr, Voeller RK. Biatrial lesion sets. J lnterv Card Electrophysiol. 2007;20:95–99. doi: 10.1007/s10840-007-9178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, Castle L, et al. The Cox-maze procedure: the Cleveland Clinic Experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Daly RC, et al. Cox-maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: Mayo Clinic Experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:30–37. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcidi JM, Jr, Doty DB, Millar RC. The maze procedure: the LDS hospital experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:38–43. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballaux PKEW, Geuzebroek GSC, van Hemel NM, et al. Freedom from atrial arrhythmias after classic maze III surgery: a 10-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(6):1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessurun ER, van Hemel NM, Defauw JAMT, et al. Results of maze surgery for lone paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;101:1559–1567. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lönnerholm S, Blomström P, Nilsson L, et al. Effects of the maze operation on health-related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;101:2607–2611. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khargi K, Hutten BA, Lemke B, et al. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg. 2005;27:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damiano RJ., Jr Alternative energy sources for atrial ablation: judging the new technology. Invited Editorial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:329–330. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melby SJ, Lee AM, Damiano RJ., Jr . Advances in surgical ablation devices for atrial fibrillation. In: Naccarelli GV, et al., editors. New Arrhythmia Technologies. Blackwell Publishing; Malden, Massachusetts: 2005. pp. 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damiano RJ, Jr, Schuessler RB, Voeller RK. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: a look into the future. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;9:39–45. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, et al. Epicardial microwave ablation on the beating heart for atrial fibrillation: the dependency of lesion depth on cardiac output. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams MR, Kourpanidis S, Casher J, et al. Epicardial atrial ablation with high intensity focused ultrasound on the beating heart. Circulation. 2001;104:II–409. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billard BE, Hynynen K, Roemer RB. Effects of physical parameters on high temperature ultrasound hyperthermia. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16:409–420. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90070-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okumura Y, Kolasa MW, Johnson SB, et al. Mechanism of tissue heating during high intensity focused ultrasound pulmonary vein isolation: implications for atrial fibrillation ablation efficacy and phrenic nerve protection. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:945–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaynor SL, Ishii Y, Diodato MD, et al. Successful performance of the Cox-maze procedure on the beating heart using bipolar radiofrequency ablation: a feasibility study in animals. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melby SJ, Gaynor SL, Lubahn JG, et al. Efficacy and safety of right and left atrial ablations on the beating heart with irrigated bipolar radiofrequency energy: A long-term animal study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(4):853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamner CE, Lutterman A, Potter DD, et al. Irrigated bipolar radiofrequency ablation with transmurality feedback for the surgical Cox-maze procedure. Heart Surg Forum. 2003;6:418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damiano RJ, Jr, Gaynor S. Atrial fibrillation ablation during mitral valve surgery using the Atricure device. Op Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;9:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lall SC, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, et al. The effect of ablation technology on surgical outcomes after the Cox-maze procedure: a propensity analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(2):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee AM, Bailey MS, Aziz A, et al. A minimally invasive full Cox-maze procedure: technique and results [abstract] Innovations: Technol Techniq Cardiothorac Vascu Surg. 2008;3(2):67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt C, Ndrepepa G, Weber S, et al. Biatrial multisite mapping of atrial premature complexes triggering onset of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen SA, Hsieh MH, Tai CT, et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1999;100:1879–1886. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nitta T, Ishii Y, Miyagi Y, et al. Concurrent multiple left atrial focal activations with fibrillatory conduction and right atrial focal or reentrant activation as the mechanism in atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf RK, Schneeberger EW, Osterday R, et al. Video-assisted bilateral pulmonary vein isolation and left atrial appendage exclusion for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(3):797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edgerton JR, Edgerton ZJ, Weaver T, et al. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClelland JH, Duke D, Reddy R. Preliminary results of limited thoracotomy: new approach to treat atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovas Electrophysio. 2007;18(12):1289–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wudel JH, Chaudhuri P, Hiller JJ. Video-assisted epicardial ablation and left atrial appendage exclusion for atrial fibrillation: extended follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yilmaz A, Van Putte BP, Van Boven WJ. Completely thoracoscopic bilateral pulmonary vein isolation and left atrial appendage exclusion for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:521–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edgerton JR, Jackman WM, Mack M. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. J. Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2007;20:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s10840-007-9177-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirak J, Jones D, Sun B, et al. Toward a definitive, totally thoracoscopic procedure for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 2008;86:1960–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee AM, Aziz A, Sakamoto S, et al. Epicardial ablation on the beating heart: limited efficacy of a novel, cooled radiofrequency ablation device. Innovations: Technol Techniq Cardiothorac Vascu Surg. 2009;4(2):86–92. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e3181a348a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scherlag BJ, Nakagawa H, Jackman WM, et al. Electrical stimulation to identify neural elements on the heart: their role in atrial fibrillation. J Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 2005;13:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s10840-005-2492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Yamanashi WS, et al. Experimental model for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation arising at the pulmonary vein-atrial junction. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheinman MM, Keung E. The year in clinical cardiac electrophysiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(20):2061–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platt M, Mandapati R, Scherlag BJ, et al. Limiting the number and extent of radiofrequency application to terminate atrial fibrillation and subsequently prevent its inducibility. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:S11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mounsey JP. Recovery from vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: effects are complex and not always predictable. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(6):709–710. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh S, Zhang Y, Bibevski S, et al. Vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: epicardial fat pad ablation does not have long-term effect. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(6):701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakamoto S, Schuessler RB, Lee A, et al. Focal ablation of epicardial ganglionated plexus: electrophysiological modification and regeneration of vagal tone in canine atria. Innovations: Technol Techniq Cardiothorac Vascu Surg. 2008;3(3):67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katritsis D, Giazitzoglou E, Sougiannis D, et al. Anatomic approach for ganglionic plexi ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(3):330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(6):816–861. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Damiano RJ, Jr, Bailey M. Multimedia Manual of Cardiothoracic (MMCTS) Online. The European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery; Jul 23, 2007. The Cox-maze IV procedure for lone atrial fibrillation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuessler RB, Kay MW, Melby SJ, et al. Spatial and temporal stability of the dominant frequency of activation in human atrial fibrillation. J Electrocardiol. 2006;39(suppl 4):S7–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berenfeld O, Mandapati R, Dixit S, et al. Spatially distributed dominant excitation frequencies reveal hidden organization in atrial fibrillation in the Langendorff-perfused sheep heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11(8):869–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sahadevan J, Ryu K, Peltz L, et al. Epicardial mapping of chronic atrial fibrillation in patients: preliminary observations. Circulation. 2004;110(21):3293–3299. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147781.02738.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nattel S, Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Brundel BJ, et al. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: lessons from animal models. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;48(1):9–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Intini A, Goldstein RN, Jia P, et al. Electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI), a novel diagnostic modality used for mapping of focal left ventricular tachycardia in a young athlete. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1250–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ramanathan C, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI): comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramanathan C, Ghanem RN, Jia P, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2004;10:422–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr. Patient-specific surgical strategy for atrial fibrillation: promises and challenge. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(9):1222–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrd GD, Prasad SM, Ripplinger CM, et al. Importance of geometry and refractory period in sustaining atrial fibrillation: testing the critical mass hypothesis. Circulation. 2005;112(9):I7–I13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim KB, Rodefeld MD, Schuessler RB, et al. Relationship between local atrial fibrillation interval and refractory period in the isolated canine atrium. Circulation. 1996;94:2961–2967. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barnette AR, Bayly PV, Zhang S, et al. Estimation of 3-D conduction velocity vector fields from cardiac mapping data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2000;47:1027–1035. doi: 10.1109/10.855929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gillinov AM, Sirak J, Blackstone EH, et al. The Cox maze procedure in mitral valve disease: predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1653–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kosakai Y. Treatment of atrial fibrillation using the Maze procedure: the Japanese experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:44–52. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]