Abstract

Microarray analysis reaches increasing popularity during the investigation of prognostic gene clusters in oncology. The standardisation of technical procedures will be essential to compare various datasets produced by different research groups. In several projects the amount of available tissue is limited. In such cases the preamplification of RNA might be necessary prior to microarray hybridisation. To evaluate the comparability of microarray results generated either by amplified or non amplified RNA we isolated RNA from colorectal cancer samples (stage UICC IV) following tumour tissue enrichment by macroscopic manual dissection (CMD). One part of the RNA was directly labelled and hybridised to GeneChips (HG-U133A, Affymetrix), the other part of the RNA was amplified according to the “Eberwine” protocol and was then hybridised to the microarrays. During unsupervised hierarchical clustering the samples were divided in groups regarding the RNA pre-treatment and 5.726 differentially expressed genes were identified. Using independent microarray data of 31 amplified vs. 24 non amplified RNA samples from colon carcinomas (stage UICC III) in a set of 50 predictive genes we validated the amplification bias. In conclusion microarray data resulting from different pre-processing regarding RNA pre-amplification can not be compared within one analysis.

1. Introduction

Microarray-based investigations of genome wide gene expression have become a popular method for the molecular characterisation of various tissue types. In molecular oncology prognosis-related genes could be identified concerning various cancer types [1–5]. Especially in colorectal carcinoma gene clusters related to metastasis, tumour recurrence or chemoradiation were described [4, 6–8]. Microarray analysis in most of these studies was not dependent on RNA amplification, as enough RNA could be isolated from the tumours. Whenever tissue is limited and a high-throughput analysis is in concern, amplification of RNA by in vitro transcription is essential. However, using amplification, one has to be sure that the RNA is amplified linear, meaning that gene expressions will be comparable between native and amplified RNA. This is necessary, as more and more data are generated with different methods, stored at the internet being available for the research community. Recently the limited comparability of gene expression profiles between studies using different techniques has been demonstrated [5]. However, there is an ongoing discussion if microarray data of non amplified and amplified RNA samples are comparable. The aim of our study was to evaluate to which extend (1) the microarray data based on amplified RNA are reproducible, (2) the expression data from amplified and native RNA are comparable, and (3) if tumour specific genes are affected by an amplification bias.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients and Experimental Procedure

Primary tumours of four patients with colorectal carcinomas stage UICC IV resected at the Department of Surgery at the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg were chosen for the analysis. No patient received neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgery. By approval of the Ethical Committee of our University and by patient consent, conformity to the ethical guidelines for human research respecting the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki was provided. After tumour enrichment by cryotomy after manual dissection (CMD) RNA was isolated from each sample [9]. One part of the RNA of each sample was hybridized to the microarray without amplification; the other part underwent amplification prior to microarray hybridization (Figure 1). For validation purpose the microarray data of amplified RNA from 31 colon carcinoma samples stage UICC III versus the microarray data of not amplified RNA from 24 colon carcinoma samples were used. Patient selection, tissue workup, and amplification protocol were equally in each group.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure. RNA was isolated from tumours after CMD; one part of the RNA underwent amplification and the other part was hybridized without preamplification to microarrays.

2.2. Sample Workup and RNA Isolation

The tissue was inserted into a cryotube (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) together with Tissue-Tek (Zakura, Zoeterwoude, Netherlands) and immediately shock frozen in liquid nitrogen after surgery and stored at −80°C until further workup. CMD was performed as recently described [9]. RNA isolation was performed in the same way from all four tissue samples using commercial kits (RNeasy-Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturers' protocol. Each sample was added to the Qiagen spin column, and centrifuged to bind the RNA to the matrix. The column was washed with the buffers provided in the kit, and the RNA was finally eluted with distilled H20. Within this procedure a DNAse (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) digestion was included following the manufacturers' suggestion. RNA quality and quantity was determined by the “Lab on a Chip” method (Bioanalyzer 2100, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, USA) following the manufacturers' instructions [10]. A total of 50 ng to 100 ng of each RNA sample was loaded/well. The analyser allows for visual examination of both the 18S and 28S rRNA bands as measure of RNA integrity.

The 3′/5′-ratios for the housekeeping genes glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphatase (GAPDH) and ß-actin supplied by the GeneChip were used as further parameters for RNA quality and to exclude partial degradation. A 3′/5′-ratio below the value of 3 was regarded as an indicator for good RNA quality according to the manufacturers' protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, USA) [11].

2.3. RNA Amplification

Amplification of RNA was performed with the Message Amp aRNA kit (Ambion, Austin (Tx), USA) according to the manufacturers' instructions, using 200 ng of total RNA for each sample. Briefly, first strand cDNA syntheses were primed with the T/Oligo (dT) primer to synthesize cDNA with a T/promoter sequence from the poly (A) tails of massages by reverse transcription. The second strand cDNA synthesis converted cDNA with the T7 promoter primer into double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) template for transcription. Following a cDNA purification step an in vitro transcription was done, generating multiple copies of aRNA from the double-stranded cDNA templates. Finally, in another purification step, unincorporated NTPs, salts, enzymes, and inorganic phosphate were removed. In a second round, the additional amplification of the RNA sample was achieved. Besides using different primers for the second round, the same reagents and methodology were used. During this second round the biotin labelling of the probe took place before the in vitro transcription step. Hereunto, for each sample, 3.75 μL of 10 mM biotin 11-CTP and 3.75 μL of 10 mM biotin-16-UTP were added and the probe dried in a vacuum centrifuge concentrator.

2.4. Labelling of “Native” RNA and GeneChip Hybridization

Biotin-labelled cRNA was generated by in vitro transcription as described previously and hybridized to the GeneChips (HG-U133A, Affymetrix) following the manufacturers' instructions. For first-strand cDNA synthesis, 9 μL (13.5 μg) of total RNA were mixed with 1 μL of a mixture of three polyadenylated control RNAs, 1 μL 100 μM T7-oligo-d(T)21-V primer (5′-GCATT AGCGGCCGCGAAA TTAATACGACTCACT ATA-GGGAGA(T)21V-3′), incubated at 70°C for 10 min and put on ice. Next, 4 μL of 5x first strand buffer, 2 μL 0.1 M DTT and 1 μL 10 mM dNTPs were added and the reaction was preincubated at 42°C for 2 min. Then 2 μL (200 U) Superscript II (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) were added and incubation continued at 42°C for 1 hour. For second strand synthesis, 30 μL of 5x second strand buffer, 91 μL of RNAse-free water, 3 mL 10 mM dNTPs, 4 μL (40 U) E. coli DNA polymerase I (Life Technologies), 1 μL (12 U) E. coli ligase (TaKaRa Biomedical Europe, Gennevilliers, France), 1 μL (2 U) RNAse H (TaKaRa) were added and the reaction was incubated at 16°C for 2 hours. Then, 2.5 mL (10 U) T4 DNA polymerase I (TaKaRa) were added at 16°C for 5 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 μL 0.5 M EDTA, the double-stranded cDNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform and the aqueous phase was recovered by phase lock gel separation (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). After precipitation, the cDNA was restored in 12 μL of RNAse-free water. Five microliters of ds cDNA were used to synthesize biotinylated cRNA using the BioArray High Yield Transcript Labeling Kit (Enzo Diagnostics, NY, USA). Labelled cRNA was purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Fragmentation of cRNA, hybridization to GeneChips, washing and staining as well as scanning of the arrays in the Gene Array scanner (Agilent) were performed as recommended by the Affymetrix Gene Expression Analysis Technical Manual. Signal intensities and detection calls for statistical analysis and hierarchical clustering were determined using the GeneChip 5.0 software.

2.5. Statistics

Significance levels of microarray results between non amplified (NA) and amplified (PA) RNA samples were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U-test (P < .05, means differecially expressed). The average signal intensity of PA/NA was calculated as fold change (FC). Unsupervised and supervised hierarchical cluster analyses of all 22.215 probe sets (HG-U 133A, Affymetrix) were performed (Spotfire, Decision Site, Somerville, USA). Differences in signal intensity of microarray results between NA versus PA were analysed regarding sequence length and chromosomal localization. Pearson correlation of signals and detection P-values from microarray results between NA versus PA were investigated.

Moreover, validation of amplification bias was done for 22.215 gene expression values (HG-U133A, Affymetrix) for 31 amplified RNA samples of colon carcinoma samples versus 24 not amplified RNA samples of colon carcinoma samples, all stage UICC III. The Pearson correlation was calculated and the mean expression values and standard deviation (log2) of 50 predictive genes for lymphatic metastasis recently described have been compared [12]. For validation purpose gene expression measures were computed with the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) method described in Irizarry et al. [12] and implemented in the R-function just RMA of the Bioconductor R package affy. The statistical analysis was performed with the open-source software R, Version 2.6.1.

3. Results

3.1. Comparability of Amplified and Non Amplified RNA

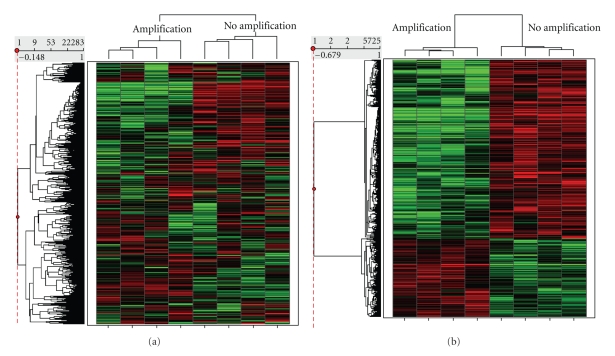

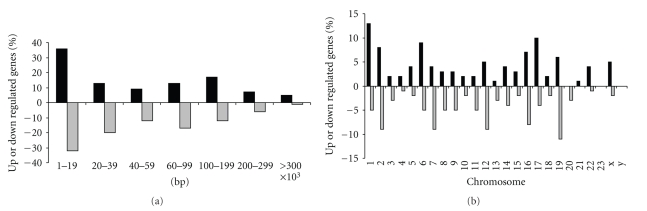

In the amplified test set 200 ng of RNA was used as the starting yield. Two rounds of amplification of RNA resulted in sufficient amounts of cRNA with good quality for microarray hybridization. The correlation of the microarray signals between non amplified and amplified RNA reached 86%–91%. The detection P-values of the microarray data correlated in 75%–81% (Table 1). An unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis including all 22.283 probe sets from the GeneChips separated all unamplified from the preamplified RNA samples (Figure 2). All samples were correctly classified regarding the method of RNA pretreatment. In the statistical analysis (Mann-Whitney U-test, P < .05) 5.725 significantly differentially expressed genes between non amplified and amplified RNA samples could be identified. In 1.182 probe sets of the microarray a significantly elevated signal intensity of amplified versus non amplified samples could be detected. In 4.543 probe sets significantly lower signal intensity between amplified versus non amplified RNA could be detected. The fold change (PA/NA) of the mean signals was between 8 (bicaudal-D (BICD) mRNA) and 13 (myosin I × b (MYO9b) mRNA). Several ribosomal RNA (e.g., 18S rRNA gene) which were included on the microarrays as internal control could be detected with a fold change of 273 between amplified vs. non amplified samples. In 36% RNA with increased FC and in 32% RNA with a decreased FC had a sequence length between 1000–19000 bp. In 5% RNA with increased FC and in 1% RNA with a decreased FC had a sequence length >300000 bp (Figure 3(a)). Thirteen per cent of genes with an increased FC were located on chromosome 1; 10% on chromosome 17; 9% on chromosome 6, and 8% on chromosome 2. Eleven per cent of genes with decreased FC were located on chromosome 19; 9% were located on chromosome 2, chromosome 7, and chromosome 12, and 8% on chromosome 16 (Figure 3(b)).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations of microarray signals and detection P-values between non amplified (NA) and amplified (PA) RNA samples from four colorectal carcinoma specimens. The RNA was isolated from identical samples and underwent either amplification or no amplification prior to microarray hybridization.

| Samples | Signals | Detection P-value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 NA versus 1 PA | 0.91 | .81 |

| 2 NA versus 2 PA | 0.89 | .75 |

| 3 NA versus 3 PA | 0.86 | .79 |

| 4 NA versus 4 PA | 0.91 | .81 |

Figure 2.

Unsupervised (a) and supervised (b) hierarchical cluster analysis of microarray results from non amplified and amplified RNA samples from colorectal carcinoma samples.

Figure 3.

Differences in total gene expressions between non amplified (NA) versus amplified (PA) RNA, regarding (a) sequence length of genes and (b) chromosomal localization.

3.2. Influence of RNA Amplification on Colorectal Cancer Specific Genes

Various genes which have been recently described participating in carcinogenesis and tumour progression in colorectal carcinomas could be identified with significantly different signals between amplified and non amplified RNA samples (e.g., WNT3, APC, and VEGF). VEGFB had a decreased FC of −5 and the APC gene −4. Several genes involved in the cell cycle (CDC5, CDC6, CDC2, CDC25C, CDC25A) were found with significantly different microarray signals with an FC between 3 and −4. Matrix metalloproteinases as MMP-11, MMP14, and MMP 15 showed decreased FC between −4 and −9 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Different gene expression values of cancer specific genes between non amplified (NA) and amplified (PA) RNA samples from colorectal carcinoma samples.

| Affy | Gb | Bases | Anotation | Avg. Signals NA | Avg. Signals PA | FC PA/NA | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 221455_s_at | NM_030753 | 56038 | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 3 (WNT3). | 20 | 78 | 4 | .04 |

| 212447_at | AF161402 | 23,589 | HSPC284 mRNA, partial cds. | 2480 | 9611 | 4 | .01 |

| 201111_at | NM_001253 | 50,649 | Brain cellular apoptosis susceptibility protein (CSE1). | 2568 | 7431 | 3 | .01 |

| 209056_s_at | NM_001253 | 62,329 | CDC5 (cell division cycle 5, S. pombe, homolog)-like (CDC5L). | 1399 | 3861 | 3 | .01 |

| 206458_s_at | NM_024494 | 54,746 | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 2B (WNT2B). | 72 | 177 | 2 | .01 |

| 207149_at | L33477 | 1,102,757 | Br-cadherin mRNA, complete cds. | 35 | 84 | 2 | .04 |

| 204731_at | NM_003243 | 225,660 | Transforming growth factor, beta receptor III (TGFBR3). | 602 | 1336 | 2 | .04 |

| 219226_at | NM_016507 | 73,062 | CDC2-related protein kinase 7 (CrkRS). | 555 | 1131 | 2 | .01 |

| 217366_at | Z37994 | 3620 | Alpha E-catenin pseudogene. | 30 | 6 | 2 | .04 |

| 208504_x_at | NM_018931 | 3321 | Protocadherin beta 11 (PCDHB11). | 33 | 11 | 2 | .04 |

| 201069_at | NM_004530 | 27,516 | Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2). | 1528 | 887 | −2 | .04 |

| 203968_s_at | NM_001254 | 15,268 | Cell division cycle 6 (CDC6). | 624 | 338 | −2 | .01 |

| 203918_at | NM_002587 | 25,296 | Protocadherin 1 (PCDH1). | 544 | 290 | −2 | .04 |

| 208756_at | U36764 | 9235 | TGF-beta receptor interacting protein 1. | 4451 | 2355 | −2 | .01 |

| 210838_s_at | L17075 | 15,944 | TGF-b superfamily receptor type I. | 277 | 127 | −2 | .01 |

| 206943_at | NM_004612 | 49,063 | Transforming growth factor, beta receptor I (TGFBR1). | 331 | 150 | −2 | .01 |

| 212143_s_at | BF340228 | 9028 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3. | 1192 | 462 | −3 | .01 |

| 202039_at | NM_004740 | 2089 | TGFB1-induced antiapoptotic factor 1 (TIAF1). | 1000 | 371 | −3 | .01 |

| 203214_x_at | NM_001786 | 18927 | Cell division cycle 2, G1 to S and G2 to M (CDC2). | 3181 | 1174 | −3 | .01 |

| 160020_at | Z48481 | 11,011 | Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1). | 1258 | 437 | −3 | .01 |

| 217010_s_at | AF277724 | 46,558 | Cell division cycle 25C splice variant 3 (CDC25C). | 211 | 61 | −3 | .01 |

| 204696_s_at | NM_001789 | 31,134 | Cell division cycle 25A (CDC25A). | 123 | 34 | −4 | .01 |

| 203527_s_at | NM_000038 | 108,353 | Adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC). | 85 | 23 | −4 | .01 |

| 210287_s_at | U01134 | 192,877 | Soluble vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor (sflt). | 143 | 37 | −4 | .01 |

| 203878_s_at | NM_005940 | 11,468 | Matrix metalloproteinase 11 (stromelysin 3) (MMP11). | 1546 | 400 | −4 | .01 |

| 203365_s_at | NM_002428 | 21,524 | Matrix metalloproteinase 15 (membrane-inserted) (MMP15). | 388 | 93 | −4 | .04 |

| 203683_s_at | NM_003377 | 3994 | Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGFB). | 422 | 78 | −5 | .01 |

| 217279_x_at | X83535 | 11,011 | Membrane-type matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP14). | 244 | 27 | −9 | .01 |

| 204380_s_at | M58051 | 15,565 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR3). | 224 | 25 | −9 | .01 |

| 207334_s_at | NM_003242 | 87,641 | Transforming growth factor, beta receptor II (TGFBR2). | 323 | 15 | −16 | .01 |

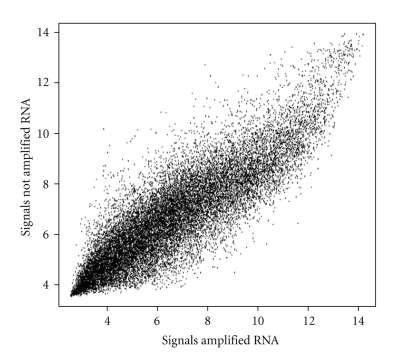

3.3. Validation of Amplification Bias

The Spearman correlation of 22.115 probe sets (Affymetrix HG-U133A) between 31 amplified RNA samples versus 24 not amplified RNA samples of colon carcinomas stage UICC III was 0.8 (Figure 4). Comparing the mean microarray signals of 50 recently described genes predictive for lymphatic metastasis only in one case an equal value could be detected (210701_at). The standard deviation in this case was less high without RNA amplification. In most other genes substantially differences were identified (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Comparison of mean signals (HG-U 133A, Affymetrix) between RNA samples of 31 colon carcinomas amplified and 24 RNA samples of colon carcinomas not amplified prior to microarray hybridization.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean signals and standard deviation (sdv) of genes which were recently described as predictive for lymphatic metastasis in colorectal carcinomas [12], between 31 amplified RNA samples of colon carcinomas and 24 RNA samples of colon carcinomas not amplified prior to microarray hybridization.

| Group | Colon carcinoma | Colon carcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples; n | 31 | 24 | ||||||

| Stage UICC | III | III | ||||||

| Amplified | yes | no | ||||||

| ProbeSet ID | gb | Gene | Bases | fold change log2 mean amplified versus non amplified | log2 mean | log2 sdev | log2 mean | log2 sdev |

| 205433_at | NM_000055 | BCHE | 64562 | 1.05 | 4.36 | 0.71 | 4.16 | 0.21 |

| 211044_at | BC006333 | TRIM14 | 49,926 | 0.8 | 3.37 | 0.18 | 4.22 | 0.24 |

| 37547_at | U85995 | PTHB1 | 476,529 | 1.32 | 5.63 | 0.61 | 4.25 | 0.17 |

| 215973_at | AF036973 | HCG4P6 | 1060 | 0.89 | 4.07 | 0.36 | 4.56 | 0.21 |

| 214376_at | AI263044 | EST | 363 | 0.99 | 4.53 | 0.36 | 4.55 | 0.14 |

| 216489_at | AB046836 | TRPM3 | 911,872 | 0.75 | 3.46 | 0.16 | 4.62 | 0.2 |

| 211201_at | M95489 | FSHR | 192,237 | 0.76 | 3.55 | 0.21 | 4.65 | 0.16 |

| 214068_at | AF070610 | BEAN | 56,130 | 0.74 | 3.45 | 0.41 | 4.66 | 0.21 |

| 216063_at | N55205 | HBBP1 | 1742 | 0.79 | 3.75 | 0.21 | 4.72 | 0.24 |

| 219791_s_at | NM_024748 | FLJ11539 | 11,373 | 0.77 | 3.67 | 0.43 | 4.77 | 0.2 |

| 209353_s_at | BC001205 | SIN3B | 50,947 | 0.92 | 4.37 | 0.23 | 4.77 | 0.29 |

| 211381_x_at | AF168617 | SPAG11 | 15,917 | 0.76 | 3.63 | 0.22 | 4.78 | 0.35 |

| 207021_at | NM_007009 | ZPBP | 155,788 | 0.74 | 3.57 | 0.2 | 4.85 | 0.17 |

| 220227_at | NM_024883 | CDH4 | 684,743 | 0.74 | 3.77 | 0.19 | 5.12 | 0.38 |

| 210701_at | D85939 | CFDP1 | 139,780 | 1 | 5.12 | 0.42 | 5.12 | 0.22 |

| 220156_at | NM_024593 | EFCAB1 | 11,825 | 0.76 | 4.04 | 0.17 | 5.32 | 0.28 |

| 209883_at | AF288389 | GLT25D2 | 101,898 | 0.89 | 4.67 | 0.77 | 5.25 | 0.19 |

| 207031_at | NM_001189 | BAPX1 | 3661 | 1.04 | 5.54 | 0.67 | 5.32 | 0.29 |

| 206885_x_at | NM_022559 | GH1 | 1636 | 0.76 | 4.14 | 0.27 | 5.47 | 0.25 |

| 212963_at | BF968960 | TM2D1 | 44,379 | 0.83 | 4.6 | 0.41 | 5.55 | 0.27 |

| 207897_at | NM_001883 | CRHR2 | 46,857 | 0.81 | 4.59 | 0.16 | 5.67 | 0.32 |

| 222083_at | AW024233 | GLYAT | 23,218 | 0.64 | 3.69 | 0.21 | 5.72 | 0.37 |

| 214149_s_at | AI252582 | ATP6V0E | 51,138 | 0.86 | 5.07 | 0.49 | 5.87 | 0.58 |

| 220332_at | NM_006580 | CLDN16 | 22,493 | 0.82 | 4.71 | 0.25 | 5.75 | 0.21 |

| 220944_at | NM_020393 | PGLYRP4 | 18,721 | 0.78 | 4.57 | 0.27 | 5.84 | 0.52 |

| 219170_at | NM_024333 | FSD1 | 19,171 | 0.91 | 5.35 | 0.24 | 5.9 | 0.36 |

| 221113_s_at | NM_016087 | WNT16 | 15,738 | 1.03 | 6.15 | 0.17 | 5.95 | 0.28 |

| 221431_s_at | NM_030959 | OR12D3 | 948 | 0.68 | 4.08 | 0.23 | 6.03 | 0.31 |

| 207936_x_at | NM_006604 | RFPL3 | 6277 | 0.64 | 3.96 | 0.36 | 6.16 | 0.47 |

| 204303_s_at | NM_014772 | KIAA0427 | 324,158 | 0.99 | 6.01 | 0.31 | 6.09 | 0.17 |

| 210272_at | M29873 | CYP2B7P1 | 26,394 | 0.74 | 4.69 | 0.23 | 6.35 | 0.38 |

| 207984_s_at | NM_005374 | MPP2 | 32,387 | 0.64 | 4.07 | 0.25 | 6.36 | 0.26 |

| 208227_x_at | NM_021721 | ADAM22 | 262,753 | 0.69 | 4.55 | 0.31 | 6.56 | 0.35 |

| 213847_at | NM_006262 | PRPH | 4997 | 0.84 | 5.63 | 0.33 | 6.71 | 0.42 |

| 215544_s_at | AL121891 | UBOX5 | 14,320 | 0.85 | 5.83 | 0.23 | 6.85 | 0.31 |

| 336_at | D38081 | TBXA2R | 12,155 | 0.74 | 5.03 | 0.24 | 6.84 | 0.28 |

| 209402_s_at | AF047338 | SLC12A4 | 24,296 | 1 | 6.97 | 0.26 | 7 | 0.25 |

| 221629_x_at | AF151022 | LOC51236 | 2948 | 0.83 | 6.04 | 0.58 | 7.29 | 0.5 |

| 219071_x_at | NM_016458 | C8orf30A | 2948 | 1.03 | 8.12 | 0.71 | 7.92 | 0.52 |

| 56829_at | H61826 | NIBP | 726,091 | 0.82 | 6.83 | 0.27 | 8.29 | 0.3 |

| 205835_s_at | AW975818 | YTHDC2 | 81,572 | 0.9 | 4.11 | 0.17 | 4.59 | 0.19 |

| 213254_at | N64803 | TNRC6B | 290,992 | 0.93 | 6.15 | 0.23 | 6.65 | 0.38 |

| 34764_at | D21851 | LARS2 | 160,261 | 1.01 | 7.13 | 0.63 | 7.04 | 0.51 |

| 209711_at | N80922 | SLC35D1 | 50,402 | 1.32 | 10.2 | 0.52 | 7.73 | 0.45 |

| 203073_at | NM_007357 | COG2 | 51,491 | 1 | 8.11 | 0.51 | 8.07 | 0.3 |

| 209174_s_at | BC000978 | FLJ20259 | 64,363 | 1.07 | 8.71 | 0.32 | 8.17 | 0.25 |

| 221884_at | BE466525 | EVI1 | 64,236 | 1.25 | 10.56 | 0.66 | 8.46 | 0.46 |

| 218160_at | NM_014222 | NDUFA8 | 15,762 | 1.22 | 11.3 | 0.38 | 9.24 | 0.47 |

| 201386_s_at | AF279891 | DHX15 | 57,098 | 1.08 | 10.44 | 0.66 | 9.64 | 0.52 |

| 202753_at | NM_014814 | PSMD6 | 13,281 | 1.14 | 11.46 | 0.44 | 10.03 | 0.46 |

4. Discussion

Gene expression profiling has become an attractive tool for tissue typing and prognostic evaluations in cancer research. For colorectal carcinoma several gene profiles dividing healthy mucosa from tumours and for prognostic classification could be identified [5, 7, 12–15]. Nevertheless there is only a limited overlap in the described gene profiles in most of these studies [5]. One reason for this finding might be the fact that there is a brought variability of applied techniques used during the analysis. Regarding the methods of tissue handling and isolation, RNA preparation, and microarray hybridization, various distributive factors may influence the results. Especially, when only small amounts of tissue can be harvested or only limited amounts of tissue are available, the yield of RNA might not be sufficient for microarray hybridization. Preprocessing of the RNA by amplification becomes indispensable. Whether samples of amplified RNA can be compared to samples with non amplified RNA is still discussed controversially. For the amplified probes, we used the linear amplification technique which is based on a double-stranded cDNA synthesis with an oligo-dT primer coupled to the T7 RNA polymerase promoter followed by an in vitro transcription into aRNA by T7 RNA polymerase [16]. This is an established technique used for RNA amplification procedures during microarray experiments [17–19]. During two rounds of amplification enough RNA in sufficient quality could be generated for microarray hybridization which supports the reliability of the method. The Affymetrix (Santa Clara, USA) GeneChip technology provides standardized protocols for microarray procedures on a commercial platform which is frequently used in gene expression profiling regarding colorectal tumours [4, 14, 20–24]. Using unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of our microarray results we observed a separation of two groups respecting the RNA pretreatment. We identified 5.725 significantly differentially expressed genes between non amplified and amplified RNA samples. As amplified and non amplified RNA referred to the same samples no separation in clusters should have been occurred. The cluster results and the identification of significantly different expressed genes demonstrate an amplification bias between native and amplified RNA. The correlation of microarray signal NA versus PA was between 86–91%. This amplification bias could be validated in a cohort of 55 RNA samples either amplified or not amplified from colon carcinoma samples (stage UICC III). The correlation of 22.115 probe set signals did reached only 80% and the comparison of 50 genes involved in lymphatic metastasis varied substantially. If the same labelled cRNA is hybridized twice to microarrays the correlation of signals is 99%. When two cRNA samples are generated from the same mRNA and hybridized to microarrays, the correlation of signals is about 99% as well. Signal correlations of 97% were reached with two separate RNA isolations and microarray hybridizations of one and the same tumour probe (data not published). Behind these findings, the identified differences between amplified and non amplified RNA are relevant. Analysing the reasons for these findings we detected that sequences with a length of bp 1000–19000 are mainly affected by differential signal intensity. This may be explained due to the more frequent amplification of shorter transcripts which may be dependent on the amount of amplification rounds. A connection of sequences located on specific chromosomes could not be identified. These findings are supported by previous studies which identified a correlation between amplification rounds and comparability between native and amplified RNA [18]. The detected alterations during RNA amplification are important, because several genes of interest involved in carcinogenesis (e.g., APC, VEGF) and tumour progression (e.g., CDC2, MMPs) were affected. When amplified and non amplified RNA are compared in the same microarray study false positive results might occur. Therefore, amplified and non amplified RNA should not be compared during microarray investigations. These findings have already been suspected previously, but have not been demonstrated in detail so far [18, 19].

5. Conclusion

Amplification of RNA by the T7-IVT is an elegant method to generate RNA in good quality and sufficient yield for microarray hybridization from as less as 200 ng of starting RNA. Nevertheless during amplification alterations occur which lead to an amplification bias compared to non amplified RNA. For this reason the microarray results of amplified and non amplified RNA samples should not be compared within the same study.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Science (BMBF) and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the University Erlangen-Nuremberg. We thank Dr. Ralph Wirtz from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics (Germany) for providing microarray data from amplified RNA samples of colon carcinomas. R. S. Croner and B. Lausen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bueno-de-Mesquita JM, van Harten WH, Retel VP, et al. Use of 70-gene signature to predict prognosis of patients with node-negative breast cancer: a prospective community-based feasibility study (RASTER) Lancet Oncology. 2007;8(12):1079–1087. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S-Y, Kim J-H, Lee H-S, et al. Meta- and gene set analysis of stomach cancer gene expression data. Molecules and Cells. 2007;24(2):200–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenawalt DM, Duong C, Smyth GK, et al. Gene expression profiling of esophageal cancer: comparative analysis of Barrett's esophagus, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120(9):1914–1921. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croner RS, Peters A, Brueckl WM, et al. Microarray versus conventional prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(2):395–404. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croner RS, Foertsch T, Brueckl WM, et al. Common denominator genes that distinguish colorectal carcinoma from normal mucosa. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2005;20(4):353–362. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghadimi BM, Grade M, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Effectiveness of gene expression profiling for response prediction of rectal adenocarcinomas to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(9):1826–1838. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frederiksen CM, Knudsen S, Laurberg S, Ørntoft TF. Classification of Dukes' B and C colorectal cancers using expression arrays. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2003;129(5):263–271. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Jatkoe T, Zhang Y, et al. Gene expression profiles and molecular markers to predict recurrence of Dukes' B colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(9):1564–1571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croner RS, Guenther K, Foertsch T, et al. Tissue preparation for gene expression profiling of colorectal carinoma: three alternatives to laser microdissection with preamplification. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2004;143(6):344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nachamkin I, Panaro NJ, Li M, et al. Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer for restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni flagellin gene. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39(2):754–757. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.754-757.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsiao LL, Dangond F, Yoshida T, et al. A compendium of gene expression in normal human tissues. Physiol Genomics. 2001;7(2):97–104. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00040.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croner RS, Förtsch T, Brückl WM, et al. Molecular signature for lymphatic metastasis in colorectal carcinomas. Annals of Surgery. 2008;247(5):803–810. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816bcd49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notterman DA, Alon U, Sierk AJ, Levine AJ. Transcriptional gene expression profiles of colorectal adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and normal tissue examined by oligonucleotide arrays. Cancer Research. 2001;61(7):3124–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groene J, Mansmann U, Meister R, et al. Transcriptional census of 36 microdissected colorectal cancers yields a gene signature to distinguish UICC II and III. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(8):1829–1836. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grade M, Hormann P, Becker S, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals a massive, aneuploidy-dependent transcriptional deregulation and distinct differences between lymph node-negative and lymph node-positive colon carcinomas. Cancer Research. 2007;67(1):41–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Gelder RN, von Zastrow ME, Yool A, Dement WC, Barchas JD, Eberwine JH. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(5):1663–1667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadenbäck J, Clapham DH, Craig D, et al. Comparison of standard exponential and linear techniques to amplify small cDNA samples for microarrays. BMC Genomics. 2005;6(1, article 61) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm J, Muyal JP, Best J, et al. Systematic comparison of the T7-IVT and SMART-based RNA preamplification techniques for DNA microarray experiments. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;52(6):1161–1167. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider J, Buneß A, Huber W, et al. Systematic analysis of T7 RNA polymerase based in vitro linear RNA amplification for use in microarray experiments. BMC Genomics. 2004;5(1, article 29) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notterman DA, Alon U, Sierk AJ, Levine AJ. Transcriptional gene expression profiles of colorectal adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and normal tissue examined by oligonucleotide arrays. Cancer Research. 2001;61(7):3124–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brueckl WM, Ballhausen WG, Förtsch T, et al. Genetic testing for germline mutations of the APC gene in patients with apparently sporadic desmoid tumors but a family history of colorectal carcinoma. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2005;48(6):1275–1281. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0949-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gmeiner WH, Hellmann GM, Shen P. Tissue-dependent and -independent gene expression changes in metastatic colon cancer. Oncology Reports. 2008;19(1):245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiese AH, Auer J, Lassmann S, et al. Identification of gene signatures for invasive colorectal tumor cells. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2007;31(4):282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin Y-H, Friederichs J, Black MA, et al. Multiple gene expression classifiers from different array platforms predict poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(2, part 1):498–507. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]