Abstract

The secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), elafin, and its biologically active precursor trappin-2 are endogeneous low-molecular weight inhibitors of the chelonianin family that control the enzymatic activity of neutrophil serine proteases (NSPs) like elastase, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G. These inhibitors may be of therapeutic value, since unregulated NSP activities are linked to inflammatory lung diseases. However SLPI inhibits elastase and cathepsin G but not proteinase 3, while elafin targets elastase and proteinase 3 but not cathepsin G. We have used two strategies to design polyvalent inhibitors of NSPs that target all three NSPs and may be used in the aerosol-based treatment of inflammatory lung diseases. First, we fused the elafin domain with the second inhibitory domain of SLPI to produce recombinant chimeras that had the inhibitory properties of both parent molecules. Second, we generated the trappin-2 variant, trappin-2 A62L, in which the P1 residue Ala is replaced by Leu, as in the corresponding position in SLPI domain 2. The chimera inhibitors and trappin-2 A62L are tight-binding inhibitors of all three NSPs with subnanomolar Kis, similar to those of the parent molecules for their respective target proteases. We have also shown that these molecules inhibit the neutrophil membrane-bound forms of all three NSPs. The trappin-2 A62L and elafin-SLPI chimeras, like wild-type elafin and trappin-2, can be covalently cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin by a tissue transglutaminase, while retaining their polypotent inhibition of NSPs. Therefore, the inhibitors described herein have the appropriate properties to be further evaluated as therapeutic anti-inflammatory agents.

Keywords: neutrophils, serine protease, protease inhibitor, protein engineering, inhibitory specificity, SLPI, Elafin

Introduction

The imbalance between protease and antiprotease activity may well be one of the major mechanism involved in inflammatory lung diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema and cystic fibrosis (reviewed in1–4). This imbalance is mainly due to a massive recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and other inflammatory cells at the inflammatory sites. Activated neutrophils release various hydrolytic agents from their granules, including proteases and glycosidases, plus antibacterial molecules and enzymes involved in the generation of oxidants.5,6 Among the proteases released from neutrophils, human neutrophil elastase (HNE; EC 3.4.21.37), proteinase 3 (Pr3 also called myeloblastin; EC 3.4.21.76) and cathepsin G (CatG; EC 3.4.21.20) are all capable of hydrolyzing elastin and other important proteins of the extracellular matrix7 like fibronectin or laminins. They, together with MMP-12 (matrix metalloprotease-12; EC 3.4.25.65) secreted by infiltrating macrophages, may therefore play key roles in the destruction of lung tissues. Neutrophil serine proteases (NSPs) are not only released into the extracellular environment, their active forms are also present at high concentrations at the surface of neutrophils. The catalytic activities and efficiencies of these membrane-bound NSPs are similar to those of their soluble forms [see (8) for a review]. Other proteases, such as collagenase MMP-8 or gelatinase MMP-9, both from neutrophils, may be important in inflammatory lung diseases.7

The activity of NSPs generally extends beyond the proteolytic breakdown of extracellular matrix proteins. They contribute to the perpetuation of inflammation through the proteolytic modification (activation or inactivation) of protease zymogens (e.g. pro-MMPs), protease inhibitors, chemokines, cytokines, growth factors and cell surface receptors.7,9–12 Hence, the extracellular forms of key enzymes like the NSPs and macrophage MMP-12 in injured lungs should be inhibited to limit both their degrading and pro-inflammatory actions.

Several endogenous inhibitors help to control the activities of extracellular NSPs in the lungs, but no single inhibitor targets all three proteases (HNE, Pr3, CatG). First, the plasma-derived serpin, α1-PI (α1-antitrypsin), preferentially targets HNE in the alveolae, although it can inhibit Pr3 and CatG in vitro.13 Another serpin, α1-antichymotrypsin, that inhibits chymotrypsin-like enzymes including CatG, is found in lung secretions but the great majority of it is present as a latent, inactive form, although it appears to be intact.14 The other extracellular inhibitors belong to the chelonianin family and comprise secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI) and elafin, together with its active precursor trappin-2 (pre-elafin) (reviewed in15). These structurally related molecules have a common fold with a four-disulfide core, the whey acidic protein (WAP) domain which is responsible for protease inhibition. Despite their similarity, they have different inhibitory spectra; elafin and trappin-2 inhibit only HNE, Pr3 and pancreatic elastase, while SLPI inhibits HNE, CatG, chymase, chymotrypsin, and trypsin. SLPI is a 107 amino-acid cationic protein containing two WAP domains that is mainly synthesized by the epithelial cells of the upper airways, where it is thought to be the major elastase inhibitor.16 Elafin (57 amino acids) was initially found in lung secretions and is derived from trappin-2 (pre-elafin), an active precursor synthesized by lung epithelial cells, Clara cells, and type II pneumocytes.15 Elafin is released from the C-terminus of its precursor trappin-2 (95 residues), perhaps by mast cell tryptase.17 Trappin-2 has a 38-residue N-terminal domain, the cementoïn domain, that contains several repeated motifs with the consensus amino acid sequence GQDPVK that is a substrate for tissue transglutaminase. This unique structural feature allows trappin-2 to be cross-linked, by transglutamination, to extracellular matrix proteins like fibronectin, while retaining its inhibitory activity.18 Trappin-2, and to a lesser extent elafin, have emerged in recent years as attractive candidates for anti-inflammatory treatment of pulmonary diseases using antiprotease(s) targeting NSPs. Indeed, trappin-2 significantly reduces inflammation in several animal models, including acute lung injury (ALI) in hamsters20 and mice,21 LPS-induced inflammation in mice22 and porcine pancreatic elastase-induced emphysema in mice.23,24 The relatively weaker anti-inflammatory action of elafin in the hamster ALI model has been attributed to the fact that trappin-2 can be conjugated to extracellular matrix proteins by tissue transglutaminase(s), while elafin cannot.20 Trappin-2 has other biological functions, in addition to this unique biochemical feature, that are independent of its antiprotease action. It has anti-inflammatory25–27 and antibacterial/antifungal properties28 that considerably reinforce its therapeutic potential.

The delivery of recombinant inhibitors targeting all three serine proteases of the neutrophil using aerosols is likely to correct the disturbed protease-inhibitor balance in lung diseases. Our efforts to produce appropriate antiproteases led us to design several inhibitors derived from SLPI and/or elafin/trappin-2 that are polyvalent, efficiently inhibiting all three proteases: HNE, Pr3, and CatG. We demonstrate that chimera inhibitors comprising both elafin and SLPI domain 2 inhibitory domains as well as trappin-2 A62L, a trappin-2 variant containing a point mutation in its inhibitory loop mutant, efficiently inhibit both soluble proteases and proteases bound to the surface membrane of neutrophils. We also evaluated the inhibitory activity of these variants when they were conjugated to fibronectin or elastin by a tissue transglutaminase. The cross-linked inhibitors still inhibited all three NSPs. Our finding provide clues to the structure-function relationships of the chelonianin inhibitors, and these were further explored by molecular modeling of reconstructed protease-inhibitor complexes. Collectively these data suggest that our designed inhibitors may be promising candidates to be used in the aerosol-based treatment of lung diseases.

Results

Combination of elafin and SLPI inhibitory domains to generate chimeras that are polyvalent NSP inhibitors

Elafin (57 amino acids) and its precursor trappin-2 (95 amino acids, also known as pre-elafin) have the same characteristic four-disulphide core-containing inhibitory domain that is similar to the WAP domain. These two inhibitors have a quite narrow spectrum of activity since they inhibit only elastases of neutrophil and pancreatic origin and neutrophil Pr3. We have previously demonstrated that both molecules have virtually identical inhibitory potency towards their target enzymes,29 implying that the N-terminally-located cementoïn domain of trappin-2 does not interfere with complex formation. SLPI (107 amino acids) is composed of two domains, each structurally similar to elafin (ca. 40% sequence identity). SLPI has a wider inhibitory spectrum than elafin/trappin-2: HNE, CatG, chymase, chymotrypsin, and trypsin are strongly inhibited, although only domain 2 (C-terminal) appears to be involved in binding to neutrophil proteases. Both inhibitors, SLPI and elafin/trappin-2 are naturally present in human lungs. SLPI is believed to be mainly in the upper airways,30 while trappin-2 and elafin, from which it is derived, are mainly produced by cells of the lower respiratory tract.31 This, together with the fact that each inhibits only two of the three major neutrophil neutral serine proteases (NSPs), suggests that inhibiting all three NSPs at the same time with a polyvalent inhibitor would help to limit their deleterious effects. We have used various strategies to design such a polyvalent inhibitor of NSPs that combines the inhibitory properties of both SLPI and elafin.

Assuming that SLPI2 (domain 2 of SLPI) binds HNE or CatG, while SLPI1 (domain 1 of SLPI) does not,32,33 we have grafted the inhibitory loop of elafin which interacts with HNE and PR3 into the corresponding loop of SLPI1 of the whole SLPI molecule. However, there is a one-residue deletion between Cys54I and Cys61I on the nonprime side of the elafin reactive site loop (RSL) and a one-residue insertion between Cys61I and Cys70I on the prime side of elafin RSL compared to the SLPI1 loop (see Fig. 1). We therefore replaced the entire region between Cys10I and Cys26I of SLPI1 with the corresponding Cys54I-Cys70I region of elafin (see Fig. 1) in the SLPI-derived mutant inhibitor denoted SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2 (see Fig. 2) to avoid a shift in the spatial position of the P2 Cys that plays a critical role in the RSL conformation. Unfortunately, we could not test its properties because we did not succeed to produce this inhibitor in sufficient amounts in our Pichia pastoris expression system under different experimental conditions due to proteolytic degradation of the molecule.

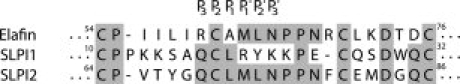

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of the regions surrounding inhibitory loops of elafin and the SLPI1 and SLPI2 domains. P3 to P3′ residues of the inhibitory loop are indicated. Residues that are conserved between at least two sequences are colored grey. The amino acids in elafin are numbered according to the trappin-2 sequence.

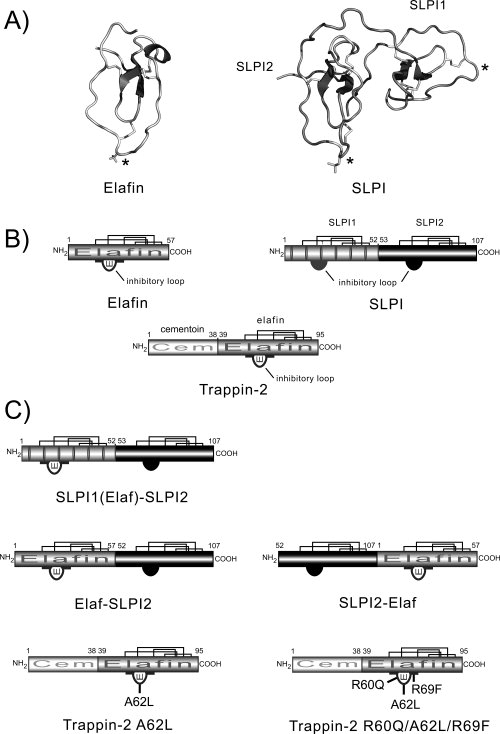

Figure 2.

Diagram of the structures of engineered inhibitors. (A) Ribbon representation of the three-dimensional structure of elafin and SLPI extracted from the elafin-PPE complex coordinate file (PDB code: 1FLE) and SLPI-bovine chymotrypsin complex coordinate file (Dr. Bode) respectively. The four disulfide bonds in each WAP domain are shown as sticks. The P1 residue in each inhibitory loop is indicated by an asterisk. The figure was generated using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org). (B) Structural organization of chelonianin inhibitors. Elafin is a 57-amino acid inhibitor (HNE and Pr3 inhibitor) derived from its active precursor trappin-2 (95 residues) by a proteolytic cleavage thought to involve mast cell tryptase (17). The N-terminal cementoïn domain of trappin-2 contains several repeated motifs rich in Gln and Lys residues that serve as transglutaminase substrates. The elafin domain is structurally homologous to both the SLPI domains (SLPI1 is N-terminal and SLPI2 is C-terminal). Only SLPI2 is believed to inhibit HNE and CatG, while SLPI1 inhibits trypsin. Also shown are the four disulfide bonds (bold lines) in each inhibitory (WAP) domain and the inhibitory loop of each WAP domain. (C) Structures of the inhibitors designed in this study. SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2 corresponds to SLPI in which the inhibitory loop of SLPI1 (amino acids 10 to 26) is replaced by the corresponding region of elafin (54–70). The Elaf-SLPI2 and SLPI2-Elaf chimeras combine the NSP-inhibiting properties of elafin (HNE and Pr3 inhibition) and SLPI2 (HNE and CatG inhibition). Trappin-2 A62L and trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F are trappin-2 mutants in which residues P3, P1, and P7′ of the inhibitory loop are replaced by the corresponding residues in SLPI2.

The second strategy was to produce double-headed chimeric inhibitors combining the elafin domain and the SLPI2 domain. Since the SLPI molecule is made up of two homologous WAP domains, each structurally similar to the elafin domain [Fig. 2(A,B)], we have replaced the noninhibitory SLPI1 domain by elafin to give Elaf-SLPI2 [Fig. 2(C)]. In the second chimera, SLPI2-Elaf, the elafin domain was introduced on the C-terminal side of SLPI2 [Fig. 2(C)]. We could predict that both chimeras will adopt the polypeptide folding motif of SLPI because there are surprisingly few intermolecular contacts between the two domains of native SLPI.34 In addition, molecular modeling studies indicate that each polyvalent chimera should bind two protease molecules simultaneously, assuming that each inhibitory domain binds its cognate protease without inducing large conformational changes (data not shown). Both mutants interacted strongly with all three NSPs, indicating that the overall structure was intact, with Ki values in the 10−11M range for NSPs. (Table I). Both chimeras inhibited HNE with essentially the Ki values as the parent inhibitors, while Elaf-SLPI2 appeared to be a slightly better inhibitor of Pr3 (Ki ≈ 1.5-fold <) than SLPI2-Elaf (Ki ≈ 3.5-fold >) or elafin (Table I). CatG had a greater affinity for both mutant inhibitors (Ki ≈ 5-fold lower for Elaf-SLPI2 and 7-fold lower for SLPI2-Elaf) than native SLPI under the same conditions (Table I). Titration experiments using active site-titrated NSPs and chimeras also confirmed that the stoechiometry of inhibition (E:I ratio) was 2:1 for HNE and 1:1 for Pr3 and CatG. Thus each domain in both chimeras was fully functional. The two chimeras bound to NSPs very rapidly, as assessed by the fact that the rate constants for association kass were much greater than 107 M−1 s−1 (Table I) indicating that they are fast-acting, pseudo-irreversible inhibitors. PPE, which has a 3D structure very similar to HNE (r.m.s deviation = 0.93 Å over 194 Cα atoms), has a significantly lower affinity (≈250-fold) for both chimeras than the NSPs, with nanomolar Ki values.

Table I.

Ki and kass Values for Wild-type Elafin, Trappin-2, SLPI, and Mutants Against Different Serine Proteases

| Neutrophil elastase |

Proteinase 3 |

Cathepsin G |

Porcine pancreatic elastase |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (M) | kass (M−1 s−1) | Ki (M) | kass (M−1 s−1) | Ki (M) | kass (M−1 s−1) | Ki (M) | kass (M−1 s−1) | |

| Elafin | 8.0 × 10−11a | 3.7 × 106a | 12.0 × 10−11a | 3.3 × 106a | NSI | – | 0.75 × 10−9a | ND |

| Trappin-2 | 3.0 × 10−11a | 3.6 × 106a | 18.0 × 10−11a | 2.0 × 106a | NSI | – | 0.32 × 10−9a | ND |

| SLPI | 1.8 × 10−11 | 5.0 × 107 | NSI | – | 20.0 × 10−11 | 3 × 107 | ≥50 × 10−9 | ND |

| Elaf-SLPI2 | 2.2 × 10−11 | 8.0× 107 | 7.6 × 10−11 | 6.0 × 107 | 3.9 × 10−11 | 4 × 107 | 6.4 × 10−9 | ND |

| SLPI2-Elaf | 5.2 × 10−11 | 1.0 × 108 | 43.0 × 10−11 | 5.0 × 107 | 2.8 × 10−11 | 5 × 107 | 4.0 × 10−9 | ND |

| Trappin-2 A62L | 1.5 × 10−11 | 2.0 × 108 | 3.7 × 10−9 | 3.0 × 106 | 6.4 × 10−9 | 2 × 107 | 20.0 × 10−9 | ND |

| Trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F | 0.56 × 10−11 | 1.0 × 108 | NSI | – | 3.2 × 10−9 | 2 × 107 | ≥20 × 10−9 | ND |

Results are the means of n = 3 experiments. For clarity, the standard deviation associated with them are not given, but they are 10% or less.

NSI, no significant inhibition; ND, not determined.

Data from Reference 29.

Although we successfully purified sufficient recombinant chimeras to study their inhibitory properties, the protein concentration appeared to be rather low and probably not compatible with the large scale production needed for aerosolisation studies with either inhibitor.

The A62L trappin-2 mutant gains CatG inhibition

We wanted to design trappin-2 mutants with a minimum number of mutations in the inhibitory loop that would bind to CatG and retain its tight-binding inhibition of HNE and Pr3 because our Pichia pastoris expression system produced large amounts of WT trappin-2 with almost no unwanted proteolysis.29 We considered that producing recombinant inhibitors at high levels is essential for the development of inhibitors intended to be used clinically. We designed a trappin-2 variant, trappin-2 A62L, based on the sequences of the inhibitory loops of SLPI and elafin/trappin-2 (see Fig. 1), in which the P1 Ala of trappin-2 was replaced by a Leu residue, the corresponding residue in SLPI domain 2, which is responsible for inhibiting CatG.

We used molecular modeling to identify the structural features -in addition to the P1 residue of the RSL- that render CatG resistant to elafin/trappin-2 inhibition. We constructed the putative elafin-CatG by superimposing CatG (PDB code: 1CGH) on the homologous PPE of the elafin-PPE complex (PDB code: 1FLE). We then attempted to identify the structural basis for the lack of inhibition of CatG by elafin. After energy minimization to relieve steric local clashes at the interface of the reconstructed complex, we calculated the electrostatic potentials for the separated molecules of the complex with DELPHI. The contours of the electrostatic potentials (see Fig. 6) displayed for each molecule of the complex revealed that two positively charged residues, Arg 60I and Arg 69I (trappin-2 sequence numbering), replaced by neutral residues in SLPI2, are involved in unfavourable positive-positive overlaps that may explain the absence of inhibition of CatG by elafin/trappin-2. We checked this hypothesis by designing a trappin-2 variant, trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F, in which Arg60 (P3 residue) was replaced by Gln and Arg69 (P7′ residue) by Phe (as in the SLPI2 inhibitory loop), in addition to the A62L substitution at position P1 (see Fig. 1). This triple trappin-2 mutant thus had the same loop sequence as the P3-P7′ region of SLPI. Surprisingly, a single point mutation at position P1 was sufficient for trappin-2 A62L to gain CatG inhibition. It was a fairly good inhibitor of CatG with a nanomolar Ki but a 20-fold greater Ki for Pr3 than WT trappin-2 and a slightly improved (2-fold) affinity for HNE (Table I). According to our hypothesis, the triple mutant, trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F behaves as a moderately better inhibitor of CatG than the A62L variant, with a twofold greater affinity. Although the three mutations in the inhibitory loop of this variant significantly gave it a better inhibition of HNE (fivefold greater affinity) than WT trappin-2, their effect on Pr3 inhibition was substantially detrimental - it did not inhibit Pr3 (Table I). Also, compared with WT trappin-2, we can notice that differences in affinity for both trappin-2 variants originate from increase or decrease in rate constants for association, the best affinities being associated with the highest kass (Table I). This suggests that selectivity of chelonianin inhibitors for NSPs is mainly due to the nature of few residues in the inhibitory loop that give it the conformation required for it to fit into the protease active site. We have previously observed that substitution of the Met P1′ in elafin dramatically altered Pr3 inhibition35 (unpublished data). This study suggests that the P3 Arg of elafin/trappin-2 is critical for Pr3 inhibition, in addition to position P1′, since neither trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F nor SLPI inhibited Pr3. The P7′ Arg69 of trappin-2 seems to be less critical for Pr3 inhibition than for CatG inhibition because it does not overlap sterically or electrostatically with Pr3 (not shown), while it does interfere with CatG inhibition (see below and Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Electrostatic surface potentials of various protease-inhibitor complexes involving chelonianins. The atomic coordinates of elafin and SLPI extracted from the elafin-PPE and SLPI-chymotrypsin complexes were used to build theoretical complexes by superimposing elafin or SLPI and CatG or Pr3 onto the inhibitor or protease component of these X-ray complexes. The electrostatic potentials were calculated for the individual molecules of each complex using the Poisson-Boltzmann method implemented in DELPHI assuming a dielectric constant of two for the interior of the proteins and 80 for the exterior, an ionic strength of 0.15 M at pH 8.0 and a temperature of 300 K. The isopotential contours of positive or negative electrostatic potentials are displayed at +5 kTe−1 (blue for the protease, cyan for the inhibitor) and −5 kTe−1 (red for the protease, magenta for the inhibitor) respectively. Each complex is displayed with inhibitor at the top and protease at the bottom of each panel. CatG, with a net charge of +23, is entirely covered with a positive potential except for the active site entrance, which is negative, as in most serine proteases. Elafin may be prevented from interacting with CatG (A, B) because of positively charged residues: Arg60I of elafin (trappin-2 numbering) on one side of the complex (A) and Arg69I on the other side overlap with the positive regions of CatG in the reconstructed complex. For clarity, the Connolly surface of elafin is also shown and the CatG structure is shown as a solid ribbon. There are no unfavorable overlaps between SLPI (green ribbon) and CatG (white ribbon) in the reconstructed SLPI-CatG complex (C), despite both proteins having a high positive charge (SLPI net charge +12). Pr3 does not interact with SLPI, although it is almost neutral (net charge +1). The electrostatic contours of each component in the theoretical complex (D) reveal that two positive areas of Pr3, contributed by Arg36E/Arg65E and Lys99E/Arg168E that protrude towards SLPI and overlap with its positive surface. (E, F) the electrostatic contours for elafin and PPE in the X-ray structure of elafin-PPE complex show that complementary (favorable) contacts may help complex formation.

In addition, we can notice that the affinity of both trappin-2 variants for pancreatic elastase is about one order of magnitude lower than that of WT trappin-2. The “SLPI-like” nature of their inhibitory loops render them poor inhibitors of PPE (Ki ≥ 2 × 10−8M), like WT SLPI which interacts loosely with PPE (Table I).

Inhibition of membrane-bound proteases by polyvalent inhibitors

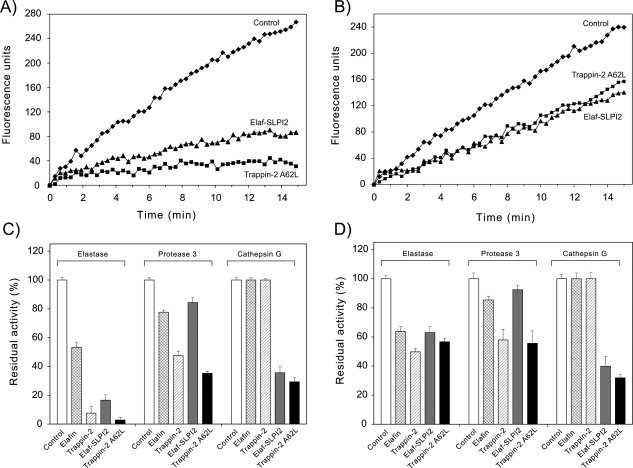

We compared the capacities of our various chelonianin inhibitors to inhibit membrane-bound and soluble NSPs. The binding of proteases to the neutrophil membrane preserves their catalytic activity against protein substrates in the immediate vicinity of activated neutrophils (see7 for review). It has been suggested that membrane-bound proteases are resistant to natural inhibitors, especially the high molecular mass serpins like α1-PI and α1-antichymotrypsin,7,36 although this is rather controversial since other data indicate that HNE at the neutrophil surface, but not Pr3 and CatG is fully controlled in vivo by α1-PI.13,37 All the inhibitors tested, both WT chelonianins and mutant inhibitors, inhibited their respective target protease(s) bound at the cell surface in a time- (not shown) and dose-dependent manner (see Fig. 3). The concave shape of the inhibition curves is indicative of a fast, tight-binding, and reversible inhibitory process.38 Elafin/trappin-2 did not inhibit membrane-bound CatG but did inhibit HNE and Pr3 and SLPI did not inhibit bound Pr3 but did inhibit CatG at the neutrophil surface (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The polyvalent inhibitors inhibited all three of the membrane-bound neutrophil proteases, but not with the same efficiency. The residual activity of each protease incubated with 100 nM inhibitor differed (see Fig. 4), reflecting different affinities (different Kis), in agreement with the results obtained with soluble proteases (Table I). HNE, which had the lowest Ki of the soluble proteases, seemed to be the most sensitive to inhibition by chimeras or trappin-2 A62L. Similarly, Pr3 which tended to have a lower affinity for the engineered inhibitors, has a higher residual activity in the presence of inhibitors than did HNE or CatG (see Fig. 4). Correlatively, we can assume that in our experimental conditions where all three proteases are present at the cell surface in unknown proportions, the partitioning of the polyvalent inhibitors on each protease is dependent on both the concentration of membrane-bound protease and the respective affinity of inhibitors. These data clearly indicate that HNE, Pr3 and CatG bound to neutrophil membranes can be inhibited by both their physiological inhibitors and our engineered polyvalent inhibitors developped in this study.

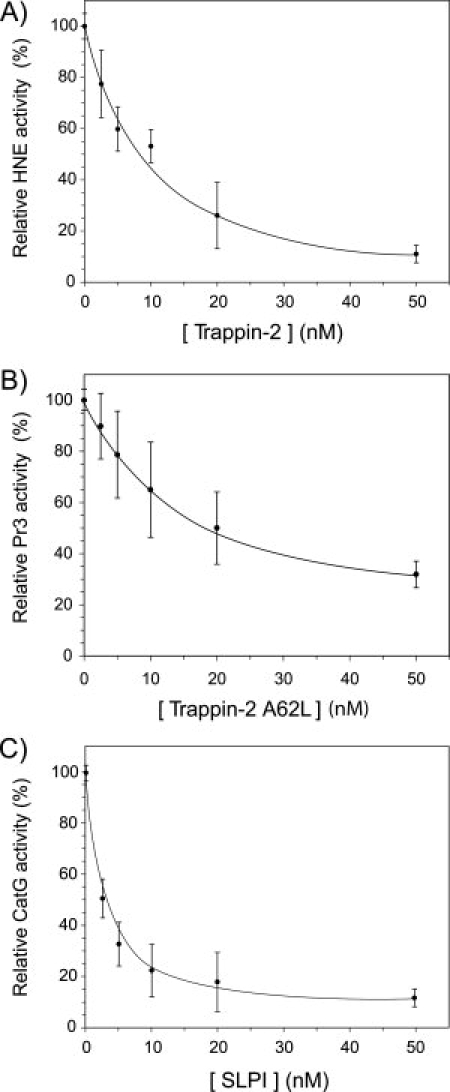

Figure 3.

Dose dependent inhibition of membrane-bound NSPs. Curves showing the inhibition of HNE (A), Pr3 (B) and CatG (C) bound to the membrane of activated neutrophils by WT trappin-2, trappin-2 A62L and WT SLPI. Purified PMNs were activated with the calcium ionophore A23187 and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with various concentrations of inhibitor. The number of cells was adjusted so that the concentration of each protease was 2 nM, as assessed by the hydrolysis of specific fluorogenic substrates. The residual protease activity was measured using specific fluorogenic substrates. Results are expressed as relative activity compared to the control experiment without added inhibitor and are the means ± SD of five separate experiments.

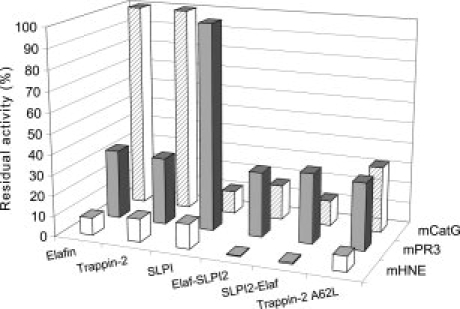

Figure 4.

Sensitivities of membrane-bound NSPs to WT chelonianins and engineered inhibitors derived from elafin/trappin-2 or SLPI. Purified PMNs were activated with the calcium ionophore A23187 and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 100 nM of: (1) WT elafin, (2) WT trappin-2, (3) WT SLPI, (4) Elaf-SLPI2, (5) SLPI2-Elaf and (6) trappin-2 A62L variant. Residual enzyme activity of each membrane-bound protease was measured using specific fluorogenic substrates. Data are expressed as percentage of residual enzyme activity (rate of substrate hydrolysis in the presence of inhibitor to the rate of substrate hydrolysis without inhibitor) and are the means of three separate experiments. Like their soluble forms, membrane-bound CatG and Pr3 were not inhibited by WT elafin/trappin-2 or WT SLPI respectively. The engineered inhibitors also inhibited all three serine proteases bound at the surface of neutrophils, as they do the soluble proteases (Table I).

Activities of polyvalent inhibitors cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin by transglutamination

We have previously shown that elafin and trappin-2 covalently bound to fibronectin by the catalytic action of a tissue transglutaminase (TGase) are still active protease inhibitors, although the rate at which they associate with their target proteases is somewhat decreased18 as a consequence of inhibitor immobilization. We now tested the capacities of our polyvalent inhibitors (chimeras and trappin-2 A62L) linked to fibronectin or elastin by TGase to inhibit all three NSPs. Trappin-2 A62L linked to fibronectin or elastin efficiently inhibited HNE and Pr3. Immobilized T2 A62L also inhibited CatG, in line with the data for soluble inhibitors (see Fig. 5). Somewhat surprisingly, Elaf-SLPI2 (see Fig. 5) and SLPI2-Elaf cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin also inhibited all three NSPs (data not shown). This suggests that the sequence motif AQEPVK of the elafin moiety thought to be involved in transglutamination39 is still accessible to the TGase active site in both chimeras. But the activites of inhibitors cross-linked to elastin were lower than those of inhibitors cross-linked to fibronectin despite the coupling conditions being the same for each inhibitor. This indicates that either fibronectin is a better TGase substrate than elastin, or that inhibitors cross-linked to elastin are less efficient than they are when bound to fibronectin. Importantly we show here for the first time that elastin-bound inhibitors still retain inhibitory activity.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of soluble NSPs by inhibitors cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin by transglutamination. Inhibitors were cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin in 96-well microplates essentially as described in (18). Inhibitors (10−6M) were incubated with tissue transglutaminase for 2 h at 37°C to form conjugated complexes with fibronectin (A,C) or elastin (B, D). The wells were washed thoroughly to remove unreacted products, and incubated with HNE (1 nM), Pr3 (2 nM), or CatG (2 nM) for 15 min at 37°C to allow protease-inhibitor complex formation. Residual enzyme activity was monitored using specific fluorogenic substrates. Representative inhibition curves (substrate hydrolysis expressed as fluorescence units vs time) are shown for the inhibition of HNE by Elaf-SLPI2 or trappin-2 A62L bound to fibronectin (A) or elastin (B). (C), (D), Graph show the residual enzyme activity for various protease-immobilized inhibitor pairs after cross-linking of the inhibitor to fibronectin (C) or elastin (D), calculated as the ratio of the rate of substrate hydrolysis in the presence of inhibitor to the rate of substrate hydrolysis without inhibitor (Control). Data are means ± SD for three separate experiments. The polyvalent inhibitors, Elaf-SLPI2 and trappin-2 A62L, inhibited all three NSPs when cross-linked to fibronectin or elastin, although Elaf-SLPI2 appeared to be less efficient against Pr3 than against HNE and CatG. As expected elafin and trappin-2 bound to fibronectin or elastin inhibited HNE and Pr3 but not CatG.

Electrostatic interactions and the selectivity of chelonianin inhibitors for NSPs

We analyzed the interfaces of reconstructed protease-inhibitor complexes by molecular modeling to elucidate the structural basis for the NSP inhibition profiles of natural and mutant inhibitors. We also performed electrostatic calculations on various protease-inhibitor complexes because electrostatic interactions are crucial for the stability of protein-protein complexes and the specificity of binding.40–42 However, electrostatic interactions may be favorable or unfavorable, and many studies have shown that electrostatic complementarity is a general feature of protein-protein interfaces,43,44 including protease-inhibitor complexes.45,46

Theoretical complexes were built using elafin extracted from the elafin-PPE complex (PDB code: 1FLE) or SLPI extracted from the SLPI-chymotrypsin complex and an appropriate protease (CatG, Pr3, HNE, or PPE). These were then superimposed on the inhibitor or protease component of the elafin-PPE or SLPI-chymotrypsin complex. Steric clashes at the protease-inhibitor interface were relieved by minimization and the electrostatic potentials of each partner of the complex in aqueous solution were calculated using DELPHI. As mentioned above, the lack of CatG inhibition by elafin appears to involve Arg60I and Arg69I (trappin-2 numbering) in elafin, two positively charged residues that overlap with the positive field surrounding the entire CatG molecule [Fig. 6(A,B)]. No other structural feature was found to be critical at the complex interface. Surprisingly, SLPI, which has a much more positive charge (net charge: +12) than elafin (net charge: +3), did interact strongly with CatG despite this protease being highly cationic (net charge: +23). The contours of electrostatic potentials revealed how these two highly positively charged proteins can interact [Fig. 6(C)]: the shape of electrostatic field around SLPI was such that there were no unfavorable overlaps with the CatG isopotential positive surface. Noteworthy, in the elafin-Pr3 complex, critical positive residues Arg60I and Arg69I of elafin are both engaged in complementary favorable contacts with areas of negative potential of the enzyme (data not shown) contributed by Asp102E, Asp213E, Asp226E (interaction with Arg60I) and Asp95E, Glu97E, Asp102E (interaction with Arg69I) of Pr3. Similar favorable electrostatic interactions were found in the elafin-HNE complex (data not shown).

Unlike CatG, Pr3, which is almost neutral (net charge: +1) is not inhibited by SLPI. This could be due to unfavorable positive-positive contacts at two locations, one involving Arg36E/Arg65E (chymotrypsinogen numbering) and the other Arg168E/Lys99E [Fig. 6(D)]. These basic residues in Pr3 that prevent SLPI binding are replaced by neutral residues in CatG (Arg36E/Gln, Lys99E/Ile, Arg168E/Leu) or have no equivalent since they are located in surface loops that are structurally different in the two enzymes. Elafin established at least two complementary (favorable) electrostatic contacts with PPE in the PPE-elafin complex, one involving Glu84I with Arg217E [Fig. 6(E)] of the enzyme and the other involving Arg69I with a negative region of PPE contributed by Asp60E, Asp97E, and Asp98E [Fig. 6(F)]. However these contacts are lost in the putative SLPI-PPE complex (Arg69I and Glu84I replaced by Phe and Met in SLPI) while at the same time unfavourable positive-positive overlaps appear between the two molecules (data not shown). Recent data47 suggest that the selectivity of SLPI2 for HNE rather than PPE is due to the P5 Tyr68I residue in SLPI, which interferes with the Ser169E-Val176E region of PPE. Our analysis revealed that SLPI Tyr68I in the conformation found in SLPI-chymotrypsin complex,34 which is quite different from that in the SLPI2-HNE complex47 (PDB code: 2Z7F), did not interfere with this region of PPE in the reconstructed complex, but rather interacted with it through Van der Waals forces (not shown). We also found that the P1 pocket of PPE was much smaller (88 Å3) than that of HNE (153 Å3) or CatG (248 Å3) as calculated by CastP,48 so that it would be more difficult for PPE to accomodate a Leu P1 residue (SLPI) than a shorter residue like Ala as found in elafin/trappin-2. Indeed, the affinity of PPE for trappin-2 A62L was significantly lower (ca. 60-fold) than its affinity for WT trappin-2.

These results suggest that both electrostatic constraints and a few critical interactions—particularly those involving the inhibitor P1 and P3 residues—play a crucial role in chelonianin selectivity.

Discussion

Published data provide compelling evidence that serine and metalloproteases are major factors in chronic, neutrophilic lung diseases such as COPD and cystic fibrosis. These proteases not only destroy many structural proteins like elastin, they also exhibit pro-inflammatory activities that help perpetuate inflammation. This suggests that inhibiting one or more proteases with protease inhibitors, delivered as recombinant therapeutics or by gene therapy, could limit the pro-inflammatory and destructive effects of proteases. NSPs have long been recognized as potential targets, but efforts have focused on neutrophil elastase rather than Pr3 and CatG, which are also released from the cells and have similar biological effects, despite some functional differences. However, the uncontrolled proteolysis in inflamed lungs is not due solely to the overwhelming of endogenous protease inhibitors by the release of massive amounts of proteases from neutrophils. It has been suggested that NSPs preserve their catalytic activity through different mechanisms,7 including tight binding to their substrates (e.g. elastin), resistance of membrane-bound enzymes to their endogenous inhibitors, or adherence of neutrophils to the extracellular matrix with the formation of a microenvironment that preserves proteolytic activity.

We have prepared and characterized mutant inhibitors derived from natural lung inhibitors as part of our ongoing efforts to design recombinant inhibitors that efficiently inhibit all three NSPs, HNE, Pr3, and CatG and could be used in an aerosol-based treatment of lung diseases. We have examined SLPI, trappin-2 and inhibitory domains from both molecules in chimera constructs. We first designed chimeric inhibitors containing elafin and domain 2 of SLPI in a single polypeptide chain, as SLPI inhibits HNE and CatG but not Pr3, while trappin-2 and elafin inhibit HNE and Pr3 with the same efficiency, but not CatG. Analysis of the three-dimensional structure of SLPI revealed that the two WAP domains, which are structurally homologous to elafin, were arranged in such a way that there were few noncovalent contacts between them.34 Thus the trypsin-inhibiting domain 1 of SLPI might be replaced by elafin to give a double-headed inhibitor. The inhibitory activities of two chimeras were evaluated, one with an N-terminal elafin followed by SLPI2 (Elaf-SLPI2), and the other with an N-terminal SLPI2 followed by elafin (SLPI2-Elaf). Both chimeras were active and almost equipotent against all three NSPs, with even lower Ki and higher kass values than the parent SLPI and elafin molecules. Although they are fast-acting inhibitors that could be of therapeutic interest, they were difficult to produce in our Pichia pastoris system because of low yields and nonspecific proteolysis. The other strategy for producing a polyvalent inhibitor was based on the observation that mutating the P1 residue of the inhibitory loop of a canonical inhibitor may dramatically change its inhibitory spectrum.19,49–50 We therefore replace the P1 Ala of trappin-2 with Leu, the corresponding P1 residue in SLPI2, a domain that strongly inhibits CatG. The resulting trappin-2 A62L inhibited CatG and, most importantly, still inhibited HNE and Pr3, despite a moderately increased Ki for its interaction with Pr3 (ca. 20-fold greater than trappin-2). CatG interacted with trappin-2 A62L less strongly than with SLPI (ca. <30-fold), but the Ki was still in the nanomolar range. Our kinetic data indicate that our engineered inhibitors, and especially trappin-2 A62L, which is readily synthesized in our expression system, have the kinetic characteristics that make them potential therapeutic inhibitors. They should be fast acting inhibitors of all three NSPs (times for total inhibition of a few milliseconds (d(t) = 5/kass [I]051), and be pseudo-irreversible inhibitors ([I]0/Ki ratio >10338), provided they are delivered in large enough quantities. We also find that trappin-2 A62L is a poor inhibitor of PPE. As human pancreatic elastase and PPE are structurally similar (90% sequence identity), human pancreatic elastase will probably also interact loosely with trappin-2 A62L, although we did not test trappin-2 A62L against it. This means that an aerosol-delivered trappin-2 A62L would have little or no impact on pancreatic elastase, even if the inhibitor entered the gastrointestinal tract. It is important to restrict inhibition to airway proteases in cystic fibrosis, so as not to aggravate any pancreatic deficiency.

It was difficult to identify the structural determinants of natural and mutant chelonianins that direct their target specificity using inhibition data. We therefore examined the 3D structures of several chelonianin-NSP complexes that had been elucidated by X-ray crystallography or were reconstructed from available enzyme and inhibitor X-ray coordinates. Analysis of the protease-inhibitor interface confirmed the importance of the inhibitor P1 residue for specificity, as previously established for canonical inhibitors. This is strikingly illustrated in the trappin-2 A62L variant that inhibited CatG due to a single amino acid substitution at P1. Inhibition data indicate that P3 Arg in trappin-2, and to a lesser extent P7′ Arg, are critical for inhibiting proteases, since trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F does not interact with Pr3. The conformations of the structurally equivalent SLPI P3 residue Gln70 in the SLPI-chymotrypsin and SLPI-HNE complexes is such that its side chain points in totally opposite directions in them (not shown). We can then speculate that the P3 Gln in the triple mutant has not the proper conformation to fit into the Pr3 active site. We found no other conspicuous stereochemical constraints at the protease-inhibitor interface of the examined complexes, even in complexes that did not form (e.g. SLPI-Pr3). However, in silico calculations indicated that favorable electrostatic interactions are correlated with high affinity for a given complex, while unfavorable repulsive electrostatic forces are associated with poor inhibition of a given protease. Hence, electrostatics may well play a key role in inhibition specificity, along with other, as yet unidentified, structural determinants. This can be correlated with our previous findings that the substrate specificity of HNE and Pr3 depends on the charge distribution around the enzyme active site.52

Our engineered molecules not only inhibit soluble proteases, they also inhibit membrane-bound proteases on activated neutrophils. Wild type inhibitors (SLPI, elafin/trappin-2) also inhibit their target proteases when they are bound at the surface of neutrophils. This is in contrast to previous studies using fixed PMNs to which exogenous protease(s) were added. They found that membrane-bound proteases were resistant to their physiologic inhibitors.36,53 Inhibition was not total under our experimental conditions, but the proteolytic activity of cell-bound NSPs was significantly reduced (by 70–90%) with 20- to 100-fold molar excess of inhibitor. Inhibition may not have been total because the polyvalent inhibitors are distributed amongst the three proteases, as all three are present at the cell surface under our experimental conditions. Also, since inhibition is reversible, the shape of the inhibition curve may be concave rather than linear because of a low [E]0/Ki ratio. Thus 100% inhibition is possible, but at a much higher inhibitor-enzyme ratio than 1:1.38,51 Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that natural and engineered chelonianins can efficiently protect substrates from destruction by membrane-bound NSPs, as shown earlier for SLPI54 or recently for α1-PI.13,37

The capacity of our inhibitors to be cross-linked to extracellular matrix proteins by a TGase enhances their therapeutic potential. They retain their capacity to inhibit NSPs under these conditions, as do WT trappin-2 and elafin,18 suggesting that they may locally protect substrates from proteolysis by NSPs. Although trappin-2 and/or elafin have been shown to be associated with lung tissues55,56 or elastin57 most probably by TGase-catalyzed cross-linking, the precise biological significance of this TGase-catalyzed conjugation remains to be elucidated. Perhaps inhibitors cross-linked to substrates by tissue TGase may be located on the surface of insoluble structures (e.g elastin), where they may efficiently inhibit protease activities. The immobilization of these inhibitors on structural proteins would increase their bioavailability. The fact that there is increased TGase activity in several inflammatory diseases,58 including cystic fibrosis,59 suggests that aerosolized recombinant inhibitors could indeed be cross-linked by TGase in vivo. Which glutamine or lysine residues are the target(s) of TGase cross-linking is not yet known, but they are probably in the GQDPVK consensus motif, or perhaps involve the C-terminal glutamine of elafin,60 both of which are present in the inhibitors studied here. We are now working to identify the transglutamination site(s) in these chelonianin inhibitors.

Our mutants probably also have all or some of the other biological functions of chelonianins (reviewed in15), in addition to being inhibitors, including intrinsic anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. They thus have many of the properties essential for use in aerosol-based treatments of inflammatory lung diseases.

Materials and Methods

Materials

HNE (EC 3.4.21.37) and PR3 (EC 3.4.21.76) were obtained from Athens Research and Technology (Athens). CatG (EC 3.4.21.20) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Vannes, France) and PPE (EC 3.4.21.36) was from Elastin Products (Owensville). The concentrations of active enzymes were measured using published methods.61,62 All the enzyme or inhibitor concentrations used for kinetic assays refer to active protein concentrations. Fluorogenic substrates were provided by Prof. Luiz Juliano (University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil). Wild type elafin and trappin-2 were produced as tag-free proteins as previously described.29 Wild type SLPI was produced in Pichia pastoris by the same procedure, using a cDNA encoding the full-length protein (a gift from Dr. Kemme, University of Darmstadt, Germany). The pPIC9 vector was from Invitrogen (Groningen, The Netherlands) and restriction enzymes were from Euromedex (Souffelweyersheim, France). Taq/Pwo DNA polymerase (Expand High Fidelity system, Roche) was from Roche (Meylan, France). Human fibronectin, bovine neck elastin and guinea pig transglutaminase (EC 2.3.2.13) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Oligonucleotides

The following primers (MWG Biotech, Les Ulis, France) were used for PCR amplifications. Restriction sites are underlined.

-Primer L1 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-TTGAATCCCCCTAACCGCTGCCAGAGTGACTG GCAG-3′. This primer encodes part of the inhibitory loop of trappin-2 (LNPPNR) followed by the C-terminal part of SLPI domain 1 (CQSDWQ).

-Primer L2 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-CGAGCGGCCGCGGAATCAAGCTTTCACAGG-3′, restriction site NotI. This primer encodes the C-terminus of SLPI (PVKA) followed by a STOP codon.

-Primer L3 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-CGACTCGAGAAAAGATCTGGAAAGTCCTTCAA AGCTGGAGTCTGTCCCATTATCTTGATC-3′, restriction site XhoI. This primer encodes the dibasic doublet KR followed by the N-terminus of SLPI domain 1 (SGKSFKAGVC) then by part of the inhibitory loop of trappin-2 (PIILI).

-Primer L4 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-GCGGTTAGGGGGATTCAACATGGCGCACCGGA TCAAGATAATGGGACAGACTCCAGCTTT-3′. This primer encodes part of SLPI domain 1 (KAGVC) preceding the inhibitory loop of trappin-2 (PIILIRCAMLNPPNR).

-Primer L5 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-CGACTCGAGAAAAGATCTG-3′, restriction site XhoI. This primer encodes the dibasic doublet KR followed by the first residue of SLPI (S).

-Primer L6 SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

5′-GCGGTTAGGGGGATTCAAC-3′. This primer encodes the C-terminal part of the inhibitory loop of trappin-2 (LNPPNR).

-Primer C1 Elaf-SLPI2

5′-CGACTCGAGAAAAGAGCGCAAGAGCCAGTCAA-3′, restriction site XhoI. This primer encodes the dibasic doublet KR used as a cleavage site by the yeast Kex2 protease followed by the N-terminal sequence of elafin (AQEPVK).

-Primer C2 Elaf-SLPI2

5′-CGAGCGGCCGCGGAATCAAGCTTTCACAGG-3′, restriction site NotI. This primer encodes the C-terminus part of SLPI (PVKA) followed by a STOP codon.

-Primer C3 Elaf-SLPI2

5′-GCCTGTTTCGTTCCCCAGGACACCCCAAACCCA ACA-3′. This junction primer encodes the C-terminus of elafin (ACFVPQ) followed by the N-terminal sequence of SLPI domain 2 (DTPNPT).

-Primer C4 Elaf-SLPI2

5′-TGTTGGGTTTGGGGTGTCCTGGGGAACGAAAC AGGC-3′. Complementary primer of C3.

-Primer C5 SLPI2-Elaf

5′-CGACTCGAGAAAAGGGATCCTGTTGACACCCC- 3′, restriction site XhoI. This primer encodes the dibasic doublet KR followed by the N-terminal sequence of SLPI2 (DPVDT).

-Primer C6 SLPI2-Elaf

5′-CGAGCGGCCGCCCCTCTCACTGGGGAAC-3′, restriction site NotI. This primers encodes the C-terminus of elafin (VPQ) followed by a STOP codon.

-Primer C7 SLPI2-Elaf

5′-TGCGTTTCCCCTGTGAAAGTCAAAGGTCCAGT CTCC-3′. This junction primer encodes the C-terminus of SLPI2 (CVSPVK) followed by the first residues of elafin sequence (VKGPVS).

-Primer C8 SLPI2-Elaf

5′-GGAGACTGGACCTTTGACTTTCACAGGGGAAA CGCA-3′. Complementary primer of C7

-Primer T1 Trappin-2 A62L

5′-CGACTCGAGAAAAGAGCTGTCACGGGAGTTCC T-3′, restriction site XhoI. This primer encodes the dibasic doublet KR followed by the N-terminal sequence of trappin-2 (AVTGVP).

-Primer T2 Trappin-2 A62L

5′-ATCCGGTGCCTCATGTTGAATC-3′. This primer introduces the Ala/Leu mutation (codon CTC, Leu) in the trappin-2 inhibitory loop (IRCLMLNP).

-Primer T3 Trappin-2 A62L

5′-GATTCAACATGAGGCACCGGAT-3′. This primer is complementary to T2

-Primer T4 Trappin-2 A62L

5′-CGAGCGGCCGCCCCTCTCACTGGGGAAC-3′, restriction site NotI. This primer corresponds to the C-terminus sequence of trappin-2 (VPQ) followed by a STOP codon.

-Primer T5 Trappin-2 A62L/R69F

5′-TCCCCCTAACTTCTGCTTGAAA-3′. This primer encodes part of trappin-2 sequence (NPPNFCLK) containing the R/F mutation (codon TTC, Phe).

-Primer T6 Trappin-2 A62L/R69F

5′-TTTCAAGCAGAAGTTAGGGGGA-3′. This primer is complementary of T5

-Primer T7 Trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F

5′-ATCTTGATCCAGTGCCTCATG -3′. This primer encodes a part of trappin-2 sequence (ILIQCLM) containing the R/Q mutation (codon CAG, Gln)

-Primer T8 Trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F

5′-CATGAGGCACTGGATCAAGAT-3′. Complementary primer of T7.

Construction of SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2, Elaf-SLPI2 and SLPI2-Elaf chimeras and trappin-2 A62L, trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F

All constructs have been cloned in pPIC9 vector using XhoI and NotI restriction sites so that cDNA inhibitors were fused downstream of the α-peptide sequence i.e immediately downstream the dibasic doublet KR. All PCR reactions were carried out using Taq/Pwo DNA polymerase (Expand High Fidelity system, Roche) at 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s and 68°C for 40 s (30 cycles).

SLPI1(Elaf)-SLPI2

The sequence encoding the last residues of SLPI1 followed by SLPI2 was first amplified by PCR using the pRH 1811 plasmid (containing the coding sequence for SLPI) as template and the forward primer L1 and the reverse primer L2. The SLPI domain 1 with its inhibitory loop (PPKKSAQCLRYKKPE) replaced by the corresponding loop of elafin (PIILIRCAMLNPPNR) was then obtained by fusing two oligonucleotides L3 and L4 and amplifying the fusion product by PCR plus L5 as forward primer and L6 as reverse primer. The resulting cDNA corresponding to SLPI domain 1 containing the inhibitory loop of trappin-2 was then fused with that encoding SLPI domain 2 (overlapping sequences), amplified with primers L5 and L2 and cloned into the yeast pPIC9 vector. The nucleotide sequence was then determined.

Elaf-SLPI2 chimera

We amplified the sequence encoding elafin followed by the first residues of the SLPI domain 2 (DTPNPT) using the pGE-SKA-B/K plasmid (containing the sequence encoding trappin-2 between BamHI and KpnI sites) as template, the forward primer C1, and the junction primer C4. We then amplified the sequence encoding SLPI domain 2 preceded by the last residues of elafin moiety (ACFVPQ) with the same PCR conditions using the pRH 1811 plasmid (containing the sequence encoding SLPI) as template, the forward primer C3 and the reverse primer C2. The two PCR products were fused and the cDNA encoding the full-length of Elaf-SLPI2 was amplified by PCR from the fusion product using C1 as forward primer and C2 as reverse primer.

SLPI2-Elaf chimera

The cDNA was obtained using the approach described above, with the primers C5, C6, C7, and C8 instead of C1, C2, C3, and C4. Both constructs were cloned into pPIC9 vector and sequenced.

Trappin-2 A62L, trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F

We used the pGE-SKA-B/K plasmid containing the trappin-2 sequence as a template to introduce by PCR the A62L mutation into the inhibitory loop with T1 and T2 primers. The PCR product encoding the N-terminal part of trappin-2 including the mutated inhibitory loop was fused with the PCR product corresponding to the C-terminal part of trappin-2 obtained by a similar PCR experiment using primers T3 and T4. The fusion product was amplified using T1 as forward primer and T4 as reverse primer to provide the cDNA encoding trappin-2 A62L. The latter was cloned into the pPIC9 vector which was used as a template to generate by PCR the cDNA encoding trappin-2 A62L/R69F (primers T1, T4, T5, and T6). The third mutation was introduced with primers T7 and T8 before final PCR with primers T1 and T4. Both constructs were sequenced prior to expression.

Expression in Pichia pastoris and purification of inhibitors

About 10 μg of a recombinant construct that had been linearized with SalI was electroporated (ECM399, BTX electroporator) into Pichia pastoris strain GS115 (his4) competent cells (Invitrogen). The His+ transformants were selected and screened for inhibitor production in small-scale experiments. Large amounts of recombinant mutant inhibitors were purified from positives clones grown in 2 L buffered glycerol-complex medium at 29°C for 2 days. The cells were harvested and suspended in 500 mL buffered methanol-complex medium containing 1% methanol to induce inhibitor production. The supernatant (ca. 500 mL) was collected from cells grown at 29°C for 1 (trappin-2 R60Q/A62L/R69F), 3 (trappin-2 A62L) or 5 days (chimeras) with a constant methanol concentration (1%) and concentrated 30-fold using a 3 kDa cutoff YM3 ultrafiltration membrane (Millipore, Paris, France). The concentrated supernatants were dialysed over a PD10 column (Amersham Biosciences) against 25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.0 (equilibrium buffer) and loaded onto a Source™ 15S column (1.6 × 15 cm) equilibrated with equilibrium buffer using a Pharmacia AKTA chromatographic system. The column was washed exhaustively with equilibrium buffer to remove unbound proteins and the bound inhibitors were eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a linear NaCl gradient (0–1 M) in equilibration buffer for 40 min. Absorbance was monitored at 220 nm because these inhibitors contain few aromatic residues. The purity of each inhibitor was assessed by high resolution Tricine SDS-PAGE63 and N-terminal amino acid sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 477A automated sequencer associated with an on-line model 120A analyzer to identify phenylthiohydantoine derivatives.

Kinetic studies with soluble neutrophil proteases

The equilibrium dissociation constant Ki for the interaction of the protease-recombinant inhibitor pairs was determined by adding substrate to an equilibrium mixture of protease and inhibitor in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, 0.75 M NaCl, 0.05% IGEPAL-CA630 for HNE and Pr3 and in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl for CatG at 37°C. Enzyme activity was measured using specific fluorogenic substrates (10 μM final) developed in our laboratory: Abz-APEEIMRRQ-EDDnp for HNE, Abz-VADCADQ-EDDnp for Pr3, and Abz-TPFSGQ-EDDnp for CatG.64 The concentration of each substrate was determined by measuring the absorbance at 365 nm, using ɛ365 nm = 17,300 M−1 cm−1 for EDDnp. The hydrolysis of Abz-peptidyl-EDDnp substrates was measured at λexc = 320 nm and λemi = 420 nm using a Hitachi F-2000 spectrofluorimeter. Assays with PPE were done in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl using Suc-(Ala)3-pNA as substrate whose hydrolysis was measured spectrophtometrically at 405 nm. The best estimates of Ki (app),the substrate-dependent Ki, were obtained by nonlinear regression analysis of the data based on the following Eq. (1) for tight binding inhibition38:

|

(1) |

where a is the relative steady state rate, [E]0 is enzyme concentration and [I]0 the inhibitor concentration. Assuming that S and I compete for binding to E, the following relationship was used to calculate the true Ki: Ki = Ki(app)/(1 + [S]0/Km), where Km is the Michaelis constant for a given enzyme-substrate pair and [S]0 is the initial substrate concentration. Ki values for inhibitors that did not display tight binding inhibition were estimated using the appropriate equation for competitive inhibition:

| (2) |

where vi is the measured reaction velocity with inhibitor and v0 without inhibitor.

Rate constants for the association (kass) between inhibitors and proteases were determined by monitoring the time dependence of association of equimolar amounts of enzyme and inhibitor at 37°C. The concentrations used to measure the residual enzyme activity at different times after adding appropriate substrate (10 μM) were in the 0.1 nM range. Experimental data were plotted according to equation (3) for second-order kinetics,51 assuming there was no dissociation of the complex during the experiment:

| (3) |

with [E]0 being the initial enzyme concentration and [E] the enzyme concentration at time t.

Inhibition assays of membrane-bound neutrophil proteases

Human neutrophils (PMNs) were purified from 4 mL samples of peripheral blood collected from healthy volunteers into EDTA-containing tubes essentially as previously reported.65 The purified PMNs were kept at room temperature with gentle shaking and washed with PBS just before use. Cell viability was checked by trypan blue exclusion.

PMNs were activated by suspending 3.106 cells/mL in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 and incubating them with the calcium ionophore A23187 (1 μM final) for 15 min at 37°C. Then they were centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min at 20°C. The PMN pellet was suspended in PBS and kept at room temperature under gentle shaking until enzymatic tests.

Purified PMNs were preincubated in 160 μL 50 mM Hepes buffer 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 with inhibitor (1 to 100 nM depending on the inhibitor) for 30 min in each microplate well at 37°C. The residual enzyme activity was measured using 10 μM of Abz-APEEIMRRQ-EDDnp for HNE, Abz-VADnVADYQ-NitroTyr (nV = norvaline) for Pr3 or Abz-TPFSGQ-EDDnp for CatG. The number of cells was adjusted so that the protease concentration was in the nanomolar range, as assessed from estimations using kcat/Km values for substrate hydrolysis by each neutrophil protease.52,64,65 The increase in fluorescence following substrate hydrolysis was recorded at λexc = 320 nm and λemi = 420 nm using a SPECTRAmax Gemini microplate fluorescence reader (Molecular Devices) that allows continuous stirring during the reaction.

Inhibitory properties of recombinant inhibitors cross-linked to fibronectin by transglutaminase

ELISA microplates (96-well, Fluoronunc Maxisorp plates) were coated (2 μg/well) with fibronectin or elastin in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) by incubation overnight at 4°C. The coated plates were washed with 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl and free sites blocked by incubation in 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2% Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C. WT inhibitors (10−6M elafin, trappin-2, SLPI) or mutant inhibitors (10−6M Elaf-SLPI2, SLPI2-Elaf or trappin-2 A62L) were incubated in wells with guinea pig liver transglutaminase (1.25 10−7M) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM DTT for 2 h at 37°C to allow the formation of cross-linked complexes with fibronectin or elastin. The plates were again extensively washed with the same buffer as above and human elastase (10−9M), proteinase 3 (2 × 10−9M) or CatG (2 × 10−9M) in an appropriate activity buffer was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C to allow the formation of protease-inhibitor complexes. Residual protease activity was then measured with 10 μM of appropriate fluorogenic substrate and a SPECTRAmax Gemini microplate reader.

Electrostatic potential analysis

The three-dimensional distributions of electrostatic potentials around each component of the protease-inhibitor complexes were calculated using the finite difference Poisson Boltzmann (FDPB) method66 as implemented in DELPHI software (INSIGHT II suite, Accelrys). The ionic strength was set to 0.15 M and the dielectric constant to four for the protein interior and 80 for the solvent. Calculations were performed at pH 8.0 at a temperature of 300 K. Formal charges, rather than all charges, were assigned as follows: arginine, lysine, N-terminus, +1; glutamate, aspartate, C-terminus, −1; and histidine, neutral. Contours of electrostatic potentials were displayed at ±5 kTe−1 using INSIGHT II.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Wolfram Bode (Munich) for providing the atomic coordinates of the chymotrypsin-SLPI complex, Jérôme Jaillet and Alexandre Gauthier for help in neutrophil purification, Dr. Michèle Brillard for N-terminal sequencing and Prof. Luiz Juliano for providing the fluorogenic substrates. The English text was edited by Owen Parkes. KB holds a joint doctoral fellowship from Inserm and the Région Centre (France).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CatG

human cathepsin G

- HNE

human neutrophil elastase

- Ki(app)

apparent dissociation constant

- PPE

porcine pancreatic elastase

- Pr3

proteinase 3

- SLPI

secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor

- NSPs

neutrophil serine proteases

- PMNs

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- RSL

reactive site loop

- TGase

tissue transglutaminase

- WT

wild type.

References

- 1.Shapiro SD. Proteinases in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:98–102. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro SD. Proteolysis in the lung. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;44:30s–32s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00000903a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen CA. Roles for proteinases in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:253–268. doi: 10.2147/copd.s2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Zheng S. Proteases and cystic fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1238–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz T, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Harwig SS, Daher K, Bainton DF, Lehrer RI. Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1427–1435. doi: 10.1172/JCI112120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faurschou M, Borregaard N. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen CA, Campbell EJ. The cell biology of leukocyte-mediated proteolysis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:137–150. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen CA. Leukocyte cell surface proteinases: regulation of expression, functions, and mechanisms of surface localization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1246–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witko-Sarsat V, Rieu P, Descamps-Latscha B, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Neutrophils: molecules, functions and pathophysiological aspects. Lab Invest. 2000;80:617–653. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiedow O, Meyer-Hoffert U. Neutrophil serine proteases: potential key regulators of cell signalling during inflammation. J Intern Med. 2005;257:319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham CT. Neutrophil serine proteases fine-tune the inflammatory response. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1317–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korkmaz B, Poutrain P, Hazouard E, de Monte M, Attucci S, Gauthier FL. Competition between elastase and related proteases from human neutrophil for binding to alpha1-protease inhibitor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:553–559. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang WS, Lomas DA. Latent alpha1-antichymotrypsin. A molecular explanation for the inactivation of alpha1-antichymotrypsin in chronic bronchitis and emphysema. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3695–3701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreau T, Baranger K, Dade S, Dallet-Choisy S, Guyot N, Zani ML. Multifaceted roles of human elafin and secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI), two serine protease inhibitors of the chelonianin family. Biochimie. 2008;90:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogelmeier C, Hubbard RC, Fells GA, Schnebli HP, Thompson RC, Fritz H, Crystal RG. Anti-neutrophil elastase defense of the normal human respiratory epithelial surface provided by the secretory leukoprotease inhibitor. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:482–488. doi: 10.1172/JCI115021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyot N, Zani ML, Berger P, Dallet-Choisy S, Moreau T. Proteolytic susceptibility of the serine protease inhibitor trappin-2 (pre-elafin): evidence for tryptase-mediated generation of elafin. Biol Chem. 2005;386:391–399. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyot N, Zani ML, Maurel MC, Dallet-Choisy S, Moreau T. Elafin and its precursor trappin-2 still inhibit neutrophil serine proteinases when they are covalently bound to extracellular matrix proteins by tissue transglutaminase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15610–15618. doi: 10.1021/bi051418i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laskowski M, Jr, Kato I. Protein inhibitors of proteinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:593–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay GM, Vachon E, Larouche C, Bourbonnais Y. Inhibition of human neutrophil elastase-induced acute lung injury in hamsters by recombinant human pre-elafin (trappin-2) Chest. 2002;121:582–588. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson AJ, Wallace WA, Marsden ME, Govan JR, Porteous DJ, Haslett C, Sallenave JM. Adenoviral augmentation of elafin protects the lung against acute injury mediated by activated neutrophils and bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:1778–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vachon E, Bourbonnais Y, Bingle CD, Rowe SJ, Janelle MF, Tremblay GM. Anti-inflammatory effect of pre-elafin in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung inflammation. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1249–1256. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janelle MF, Doucet A, Bouchard D, Bourbonnais Y, Tremblay GM. Increased local levels of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor are associated with the beneficial effect of pre-elafin (SKALP/trappin-2/WAP3) in experimental emphysema. Biol Chem. 2006;387:903–909. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doucet A, Bouchard D, Janelle MF, Bellemare A, Gagne S, Tremblay GM, Bourbonnais Y. Characterization of human pre-elafin mutants: full antipeptidase activity is essential to preserve lung tissue integrity in experimental emphysema. Biochem J. 2007;405:455–463. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallenave JM, Cunningham GA, James RM, McLachlan G, Haslett C. Regulation of pulmonary and systemic bacterial lipopolysaccharide responses in transgenic mice expressing human elafin. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3766–3774. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3766-3774.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henriksen PA, Hitt M, Xing Z, Wang J, Haslett C, Riemersma RA, Webb DJ, Kotelevtsev YV, Sallenave JM. Adenoviral gene delivery of elafin and secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor attenuates NF-kappa B-dependent inflammatory responses of human endothelial cells and macrophages to atherogenic stimuli. J Immunol. 2004;172:4535–4544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler MW, Robertson I, Greene CM, O'Neill SJ, Taggart CC, McElvaney NG. Elafin prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced AP-1 and NF-kappaB activation via an effect on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34730–34735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baranger K, Zani ML, Chandenier J, Dallet-Choisy S, Moreau T. The antibacterial and antifungal properties of trappin-2 (pre-elafin) do not depend on its protease inhibitory function. FEBS J. 2008;275:2008–2020. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zani ML, Nobar SM, Lacour SA, Lemoine S, Boudier C, Bieth JG, Moreau T. Kinetics of the inhibition of neutrophil proteinases by recombinant elafin and pre-elafin (trappin-2) expressed in Pichia pastoris. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2370–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sallenave JM, Si Tahar M, Cox G, Chignard M, Gauldie J. Secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor is a major leukocyte elastase inhibitor in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:695–702. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallenave JM, Shulmann J, Crossley J, Jordana M, Gauldie J. Regulation of secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI) and elastase-specific inhibitor (ESI/elafin) in human airway epithelial cells by cytokines and neutrophilic enzymes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:733–741. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.6.7946401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramps JA, van Twisk C, Appelhans H, Meckelein B, Nikiforov T, Dijkman JH. Proteinase inhibitory activities of antileukoprotease are represented by its second COOH-terminal domain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1038:178–185. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van-Seuningen I, Davril M. Separation of the two domains of human mucus proteinase inhibitor: inhibitory activity is only located in the carboxy-terminal domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:1587–1592. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grutter MG, Fendrich G, Huber R, Bode W. The 2.5 Å X-ray crystal structure of the acid-stable proteinase inhibitor from human mucous secretions analysed in its complex with bovine alpha-chymotrypsin. EMBO J. 1988;7:345–351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nobar SM, Zani ML, Boudier C, Moreau T, Bieth JG. Oxidized elafin and trappin poorly inhibit the elastolytic activity of neutrophil elastase and proteinase 3. FEBS J. 2005;272:5883–5893. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell EJ, Campbell MA, Owen CA. Bioactive proteinase 3 on the cell surface of human neutrophils: quantification, catalytic activity, and susceptibility to inhibition. J Immunol. 2000;165:3366–3374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korkmaz B, Attucci S, Jourdan ML, Juliano L, Gauthier F. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase by alpha1-protease inhibitor at the surface of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Immunol. 2005;175:3329–3338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bieth JG. Theoretical and practical aspects of proteinase inhibition kinetics. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:59–84. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schalkwijk J, Wiedow O, Hirose S. The trappin gene family: proteins defined by an N-terminal transglutaminase substrate domain and a C-terminal four-disulphide core. Biochem J. 1999;340:569–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheinerman FB, Norel R, Honig B. Electrostatic aspects of protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norel R, Sheinerman F, Petrey D, Honig B. Electrostatic contributions to protein-protein interactions: fast energetic filters for docking and their physical basis. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2147–2161. doi: 10.1110/ps.12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheinerman FB, Honig B. On the role of electrostatic interactions in the design of protein-protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:161–177. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braden BC, Poljak RJ. Structural features of the reactions between antibodies and protein antigens. FASEB J. 1995;9:9–16. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.1.7821765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epa VC, Colman PM. Shape and electrostatic complementarity at viral antigen-antibody complexes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;260:45–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05783-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villoutreix BO, Getzoff ED, Griffin JH. A structural model for the prostate disease marker, human prostate-specific antigen. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2033–2044. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreau T, Gauthier F. Homology modelling of rat kallikrein rK9, a member of the tissue kallikrein family: implications for substrate specificity and inhibitor binding. Protein Eng. 1996;9:987–995. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.11.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koizumi M, Fujino A, Fukushima K, Kamimura T, Takimoto-Kamimura M. Complex of human neutrophil elastase with 1/2SLPI. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2008;15:308–311. doi: 10.1107/S0909049507060670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otlewski J, Jaskolski M, Buczek O, Cierpicki T, Czapinska H, Krowarsch D, Smalas AO, Stachowiak D, Szpineta A, Dadlez M. Structure-function relationship of serine protease-protein inhibitor interaction. Acta Biochim Pol. 2001;48:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buczek O, Koscielska-Kasprzak K, Krowarsch D, Dadlez M, Otlewski J. Analysis of serine proteinase-inhibitor interaction by alanine shaving. Protein Sci. 2002;11:806–819. doi: 10.1110/ps.3510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bieth JG. In vivo significance of kinetic constants of protein proteinase inhibitors. Biochem Med. 1984;32:387–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(84)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korkmaz B, Hajjar E, Kalupov T, Reuter N, Brillard-Bourdet M, Moreau T, Juliano L, Gauthier F. Influence of charge distribution at the active site surface on the substrate specificity of human neutrophil protease 3 and elastase. A kinetic and molecular modeling analysis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1989–1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Owen CA, Campbell EJ. Angiotensin II generation at the cell surface of activated neutrophils: novel cathepsin G-mediated catalytic activity that is resistant to inhibition. J Immunol. 1998;160:1436–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rice WG, Weiss SJ. Regulation of proteolysis at the neutrophil-substrate interface by secretory leukoprotease inhibitor. Science. 1990;249:178–181. doi: 10.1126/science.2371565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nara K, Ito S, Ito T, Suzuki Y, Ghoneim MA, Tachibana S, Hirose S. Elastase inhibitor elafin is a new type of proteinase inhibitor which has a transglutaminase-mediated anchoring sequence termed “cementoin”. J Biochem. 1994;115:441–448. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshida N, Egami H, Yamashita J, Takai E, Tamori Y, Fujino N, Kitaoka M, Schalkwijk J, Ogawa M. Immunohistochemical expression of SKALP/elafin in squamous cell carcinoma of human lung. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muto J, Kuroda K, Wachi H, Hirose S, Tajima S. Accumulation of elafin in actinic elastosis of sun-damaged skelafin binds to elastin and prevents elastolytic degradation. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1358–1366. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maiuri L, Luciani A, Giardino I, Raia V, Villella VR, D'Apolito M, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Guido S, Ciacci C, Cimmino M, Cexus ON, Londei M, Quaratino S. Tissue transglutaminase activation modulates inflammation in cystic fibrosis via PPARgamma down-regulation. J Immunol. 2008;180:7697–7705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinert PM, Marekov LN. The proteins elafin, filaggrin, keratin intermediate filaments, loricrin, and small proline-rich proteins 1 and 2 are isodipeptide cross-linked components of the human epidermal cornified cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17702–17711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rao NV, Wehner NG, Marshall BC, Sturrock AB, Huecksteadt TP, Rao GV, Gray BH, Hoidal JR. Proteinase-3 (PR-3): a polymorphonuclear leukocyte serine proteinase. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;624:60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boudier C, Bieth JG. The proteinase: mucus proteinase inhibitor binding stoichiometry. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4370–4375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Korkmaz B, Attucci S, Moreau T, Godat E, Juliano L, Gauthier F. Design and use of highly specific substrates of neutrophil elastase and proteinase 3. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:801–807. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0139OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Attucci S, Korkmaz B, Juliano L, Hazouard E, Girardin C, Brillard-Bourdet M, Réhault S, Anthonioz P, Gauthier F. Measurement of free and membrane-bound cathepsin G in human neutrophils using new sensitive fluorogenic substrates. Biochem J. 2002;366:965–970. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharp KA, Honig B. Electrostatic interactions in macromolecules: theory and applications. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1990;19:301–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]