Abstract

Lys67 is essential for the hydrolysis reaction mediated by class C β-lactamases. Its exact catalytic role lies at the center of several different proposed reaction mechanisms, particularly for the deacylation step, and has been intensely debated. Whereas a conjugate base hypothesis postulates that a neutral Lys67 and Tyr150 act together to deprotonate the deacylating water, previous experiments on the K67R mutants of class C β-lactamases suggested that the role of Lys67 in deacylation is mainly electrostatic, with only a 2- to 3-fold decrease in the rate of the mutant vs the wild type enzyme. Using the Class C β-lactamase AmpC, we have reinvestigated the activity of this K67R mutant enzyme, using biochemical and structural studies. Both the rates of acylation and deacylation were affected in the AmpC K67R mutant, with a 61-fold decrease in kcat, the deacylation rate. We have determined the structure of the K67R mutant by X-ray crystallography both in apo and transition state-analog complexed forms, and observed only minimal conformational changes in the catalytic residues relative to the wild type. These results suggest that the arginine side chain is unable to play the same catalytic role as Lys67 in either the acylation or deacylation reactions catalyzed by AmpC. Therefore, the activity of this mutant can not be used to discredit the conjugate base hypothesis as previously concluded, although the reaction catalyzed by the K67R mutant itself likely proceeds by an alternative mechanism. Indeed, a manifold of mechanisms may contribute to hydrolysis in class C β-lactamases, depending on the enzyme (wt or mutant) and the substrate, explaining why different mutants and substrates seem to support different pathways. For the WT enzyme itself, the conjugate base mechanism may be well favored.

Keywords: enzyme mechanism, class C β-lactamase, K67R, general base, deacylation

Introduction

Class C β-lactamases are among the most commonly clinically observed β-lactamases, conferring bacterial resistance to the β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins and cephalosphorins.1,2 The hydrolysis reaction catalyzed by class C β-lactamases consists of two steps, acylation and deacylation [Fig. 1(a)].3,4,5 In the acylation half of the reaction, Ser64 attacks the β-lactam ring carbon and forms a covalent acyl-enzyme complex. In the deacylation step, the catalytic water reacts with the covalent linkage between the enzyme and the substrate, leading to the release of the hydrolyzed product. Both acylation and deacylation reactions proceed through a high-energy tetrahedral transition state.

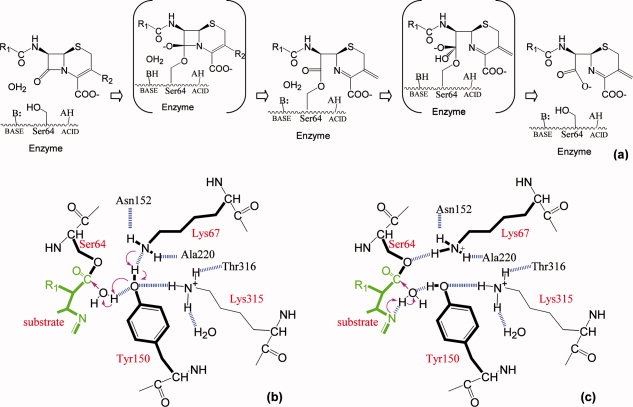

Figure 1.

Conjugate base and substrate-activated catalysis hypotheses for deacylation reaction. (a) Reaction coordinates for Class C β-lactamase catalysis. The reaction proceeds through a precovalent enzyme-substrate complex, a high-energy acylation transition state, an acyl-enzyme complex, a high-energy deacylation transition state to finally release the product and regenerate the free enzyme. (b) Schematic diagram of the conjugate base hypothesis. Arrows indicate the electron transfer direction and the dashed lines show the hydrogen bonds observed in the transition state analog structure except the one between Lys67 and Tyr150, which is not present in the transition state analog structure but observed in acyl-enzyme structures. (c) Schematic diagram of the substrate-activated catalysis. The proton from the catalytic water is transferred to the substrate ring nitrogen while Tyr150 stabilizes the water.

A series of proton transfer take place along the reaction coordinate. During acylation the catalytic nucleophile, Ser64, is deprotonated and a proton is also transferred to the leaving group, the β-lactam ring nitrogen [Fig. 1(a)]. In deacylation, it is believed that a general base activates the structurally conserved deacylating water whereas a general acid may be needed to reprotonate Ser64. Despite many experimental and theoretical studies,3,6,7 the identities of the general bases and acids are still intensely debated, particularly for the deacylation step.8

The roles of two essential active site residues, Lys67 and Tyr150, lie in the center of several proposed mechanisms for the general base/acid catalysis in the deacylation reaction.6,9–11 A tyrosinate hypothesis suggests that a deprotonated Tyr150 acts as the general base/acid alone.3,12 A conjugate base hypothesis postulates that a neutral Tyr150 and a neutral Lys67 function together to deprotonate the catalytic water: the proton transfer from the water to Tyr150 is coordinated with another transfer of the Try150 hydroxyl hydrogen to Lys67 (see Fig. 1).7 A third substrate-assisted catalysis model proposes that the ring nitrogen, in close proximity to the catalytic water on its attacking course toward the reaction center, stabilizes the water and can function as the general base.13,14 It is also conceivable that different mechanisms are involved, especially in different mutants, in a manifold of pathways with related energy coordinates. All three hypotheses are consistent with X-ray crystal structures of the acyl-enzyme complex and deacylation transition state analogs.5,12,14–18 In the deacylation transition state analog structures using boronic acid compounds, Tyr150Oη interacts with the boronic acid oxygen that mimics the catalytic water in the tetrahedral transition state, suggesting a direct role for Tyr150 in the activation of the catalytic water.8,17 The β-lactam ring nitrogen is also implicated when an acyl-enzyme complex with loracarbef is superimposed onto the deacylation transition state analog structure, showing that the ring nitrogen in the acyl-enzyme is ∼2.5 Å away from the same boronic acid oxygen in the deacylation transition state analog and suggesting that the ring nitrogen could interact with the catalytic water during its attack on the covalent acyl-enzyme linkage.8,14

Previous biochemical and computational efforts have produced mixed support for these hypotheses. Although small-molecule solution experiments suggested that a Tyr150-like phenolic group was negatively charged at pH 7,19 NMR studies on the class C β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii GN346 suggest that the pKa of Tyr150 is above pH 11 in the apo-enzyme,20 disfavoring the tyrosinate hypothesis. The substrate-assisted catalysis model is supported by the observations that certain substrate analogs lacking the equivalent nitrogen were trapped in the acyl complex and that β-lactam compounds with displaced nitrogens acted as inhibitors.13,21 Some experiments have also suggested that the pKa of the lactam nitrogen may be between pH 5 and 6, consistent with the proposed general base function.22 However, the observation that depsipeptides are good β-lactamase substrates cast doubt on the substrate-assisted catalysis model because these substrates do not have the lactam nitrogen,23 suggesting at least that this mechanism can not be used to explain all β-lactamase reactions. The conjugate base hypothesis was favored by recent QM/MM calculations.7 However,the requirement of a neutral Lys67 in this process can not be reconciled with the results from the K67R mutants of class C β-lactamases from Citrobacter freundii GN346 and Enterobacter cloacae 908R.9,6 For E. cloacae 908R class C β-lactamase, the K67Q mutation drastically impaired the enzyme activity.6 In the K67R mutant, however, the deacylation rate dropped by only 2- to 3-fold, whereas the efficiency of the acylation reaction was decreased by 25- to 100-fold. These results suggest that Lys67's role in deacylation is primarily electrostatic.

We recently determined a deacylation transition state analog structure of AmpC class C β-lactamase from E. coli.8 The 1.07 Å resolution of this X-ray crystal structure has revealed that the hydrogen on the Tyr150 hydroxyl group is donated to the boronic acid oxygen atom mimicking the catalytic water. The fact that Tyr150 is protonated is not easily reconciled with the tyrosinate hypothesis, but it does not strictly rule it out. Although the ultra-high resolution structure is potentially consistent with both the substrate-assisted hypothesis and the conjugate base mechanism, we favored the former particularly because of the studies on the K67R mutants. Because of the importance of the K67R mutant in differentiating these mechanisms, we have reinvestigated the mutant through both biochemical and structural methods, using AmpC as a model system. In contrast with previous results, we observe substantial decreases in both acylation and deacylation efficiencies. X-ray crystallographic studies also illuminated the active site configurations of both the apo K67R mutant and the transition state analog complex, which were unavailable in the previous studies. The implications of these results for the conjugate base and substrate-assisted catalysis hypotheses are discussed.

Results

K67R activity. The activities of AmpC wild type and the K67R mutant were assayed using cephalothin as the substrate. When the measurements were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation, the resulting kcat/Km and kcat values reflect the efficiency of acylation and deacylation steps, respectively (deacylation is the slow step of the reaction and the rate of acylation is comparable to the formation of the Michaelis-Menten complex).24 The kcat values for the wild type and the K67R mutant were 275.0 s−1 and 4.5 s−1, respectively. The 61-fold decrease suggested that the deacylation rate was affected by the mutation. The kcat/Km value was down by close to 2200-fold, from 9390 mM−1 s−1 to 4.3 mM−1 s−1, suggesting that the acylation reaction was greatly impaired by the substitution as well. These results are not easily reconciled with a purely electrostatic role of Lys67, unless the substitution has disrupted the active site structure. To investigate this we turned to X-ray crystallography.

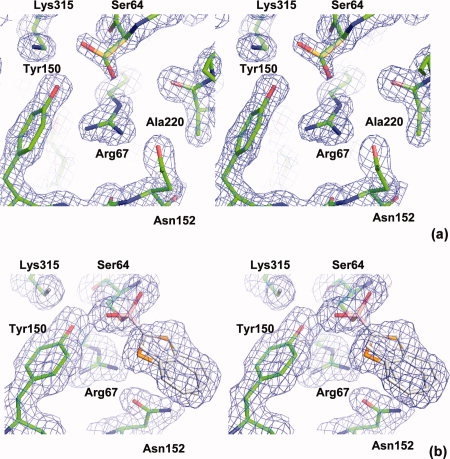

K67R mutant structures. To understand the structural basis for the activity decrease and to study the interactions between the mutant and the substrate, we determined the structures of an apo K67R AmpC mutant and a deacylation transition state analog complex using benzo(b)thiophene-2-boronic acid (bzb). Both crystallized in the C2 space group with a unit cell similar to previously determined AmpC structures, with two monomers per asymmetric unit. The apo structure was solved to 1.5 Å, with an R value of 16.6% and Rfree of 19.9% [Fig. 2(a)] (Table I). The complex structure was determined to 1.85 Å, with an R value of 16.3% and Rfree of 20.3% [Fig. 2(b)]. Arg67 is well ordered in both structures. Ser64 adopts two conformations in the apo structure whereas the benzo(b)thiophene ring also displays two conformations in the complex (a pseudo-symmetric ring flip).

Figure 2.

Stereo views of the electron densities in the active site. 2Fo-Fc maps are shown in blue at 1.5 σ contour level. (a) Apo K67R mutant. All key catalytic residues are well ordered except for Ser64, which displays an alternative conformation (gold). The minor conformation (green) is the one observed in the wild type apo structure. (b) K67R deacylation transition state analog complex with benzo(b)thiophene-2-boronic acid. The benzo(b)thiophene ring (white) displays two conformations, involving a ring flip.

Table I.

Crystallographic Statistics for AmpC K67R Mutant Structures

| Data collection | apo | bzb complex |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | C2 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a (Å) | 118.348 | 118.043 |

| b (Å) | 76.564 | 76.949 |

| c (Å) | 97.702 | 97.831 |

| α (°) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β (°) | 115.82 | 116.23 |

| γ (°) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–1.5 (1.55–1.50)a | 50.00–1.85 (1.92–1.85) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 4.6 (44.8) | 4.3 (43.0) |

| I/σI | 16.7 (1.96) | 15.1 (2.41) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.7 (90.9) | 97.2 (97.5) |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork/Rfree | 16.6 %/19.9% | 16.3%/20.3% |

| R.m.s deviationsc | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.236 | 1.552 |

| Ramachandran plotd | ||

| Most favored region | 92.1 | 92.0 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 7.9 | 8.0 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

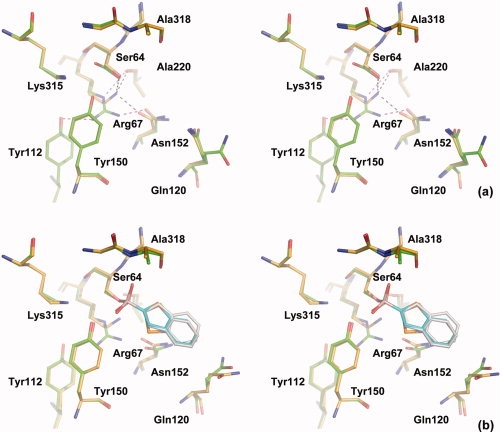

Despite the larger size of the arginine vs lysine sidechain, there are only minor changes in the overall active site conformation in both the apo and complex K67R structures (see Fig. 3). The hydrogen bonding pattern for residue 67 does change slightly. In the wild type apo structure, Lys67 is buried and its Nζ hydrogen bonds with Ser64Oγ (2.8 Å), Ala220O (2.9 Å), and Asn152Oδ1 (2.6 Å) atoms.25 Although a hydrogen bond between Lys67Nζ and Tyr150Oη is prerequisite for the conjugate base hypothesis, it is only observed in acyl-enzyme complex structures and not in the apo enzyme. The distance between these two atoms is 3.3 Å but the geometry is not suitable for a hydrogen bond. In the mutant, Arg67 adopts a side chain conformation similar to the wild type lysine except at the last X4 angle. As a result, the end of the arginine guanidinium group stacks against the Tyr150 ring, while hydrogen bonding with Tyr112Oη (2.9 Å) and Asn152Oδ1 (2.6 Å) (Fig. 3). The distance between Arg67Nɛ and Ala220O is 3.5 Å. The bulkier arginine side chain also pushes the side chains of Tyr150 and Asn152 slightly outward. Besides the substitution, the most notable change in the active site is probably the alternate conformation adopted by Ser64 (Fig. 2). Although this conformation has been observed in apo AmpC structure before (Kerim Babaoglu and Brian Shoichet, unpublished data), it is never the predominant conformation. In K67R, on the other hand, the electron density suggests that this alternative conformation does predominate, probably reflecting the loss of the hydrogen bond between Lys67Nζ and Ser64Oγ: although the Nɛ and Nη2 atoms of Arg67 are close to the minor conformation of Ser64Oγ, with distances of 3.3 Å and 3.2 Å, respectively, no hydrogen bond can be formed because of the geometrical restrictions [Fig. 2(a)]. Similarly, there is no hydrogen bond between Arg67 and Tyr150: only Arg67Nη1 is within hydrogen bond distance (3.3 Å) to Tyr150Oη, but it is directly above the phenol ring of the tyrosine.

Figure 3.

Stereo views of the wild type and K67R AmpC active sites. The residues and compound in the wild type (apo: pdb ID 1KE4; complex: 1C3B) are shown in gold and cyan, whereas those in the mutant are shown in green and white. (a) Apo enzyme. Hydrogen bonds involving residue 67 are shown in black and purple, for the wild type and mutant, respectively. (b) Deacylation transition state analog with benzo(b)thiophene-2-boronic acid.

The mutant complex structure also closely resembles that of the wild type.17 There is no significant change in the positions of Tyr150, Ser64 and the transition state analog in the complex state. In the wild type complex structure, Lys67 hydrogen bonds with Ser64Oγ (2.6 Å), Ala220O (3.0 Å), and Asn152Oδ1 (2.7 Å), similar to what is observed in the wild type apo structure. Arg67 adopts a conformation similar to that in the apo mutant structure with some very minor changes that brings the arginine guanidinium group closer to Ala220 and Asn152. As a result, the end group of Asn152 rotates slightly by ∼60 degrees. Like in the apo state, there is no hydrogen bond between Arg67 and Ser64 or Tyr150, and the arginine hydrogen bonds with Tyr112Oη (3.3 Å to Arg67Nη1), Asn152Oδ1 (2.6 Å to Arg67Nη2), and Ala220O (2.9 Å to Arg67Nɛ). Lys315 conformation is the same in the complex and apo mutant structures, as well as the apo wild type structure and some other transition state analog structures, but is slightly different in the wild type complex structure with bzb. Both conformations establish a hydrogen bond with Tyr150, which may be the most important contribution by Lys315 to catalysis. The difference between the two Lys315 conformations in the mutant and wild type bzb complex structures may not be catalytically significant and may also be within the margin of refinement error considering the resolutions of these structures.

Discussion

Despite the extensive studies on class C β-lactamases, the details of their catalytic mechanism have remained elusive, especially for the deacylation reaction. Central to this debate is the protonation states of two essential catalytic residues, Tyr150 and Lys67. NMR studies and an ultrahigh resolution complex structure have suggested that Tyr150 is neutral in the apo enzyme and most likely so throughout the reaction.8,20 Previous experiments on K67R mutants of two class C β-lactamases indirectly suggest that Lys67 is charged, at least in the acyl-enzyme complex, by demonstrating that the Lysine → Arginine substitution had little effect on the deacylation reaction.6,9 Our results on K67R AmpC suggest otherwise, showing that an arginine substitution of Lys67 substantially diminishes both acylation and deacylation. The protonation state of Lys67 is again in doubt.

The new observations from K67R AmpC do not answer the question of whether Lys67 is charged or neutral in the apo enzyme or in the transition state. It does suggest that the contribution of Lys67 to the reaction appears more than electrostatic, particularly considering that the active site adopts nearly identical conformations in the wild type and the K67R mutant. The basic conclusion we can draw from these studies is that the activity of K67R mutant does not suggest Lys67 is charged in the acyl-enzyme complex and therefore does not disfavor the conjugate base catalysis mechanism, as we previously concluded.8

Taking all evidence together, the conjugate base hypothesis may be the one favored by most experimental and computational studies and may be the predominant mechanism for the wild type AmpC β-lactamase (though we do not exclude a role for substrate-assisted catalysis, see later). Recent studies on the evolutionarily related Penicillin-Binding Protein 5 (PBP5) and on the class A β-lactamase TEM-1 provide further indirect support for the participation of a neutral Lys67 along the reaction coordinate. Like AmpC, all three enzymes share the conserved Ser-X-X-Lys motif in the active site, with Ser being the central catalytic residue and Lys playing a crucial role in the general base/acid catalysis. The corresponding lysine residues in PBP5 (Lys47) and TEM-1 (Lys73) have been shown to have lower pKa than that in solution.26,27 For PBP5, experimental and computational studies suggest that a free-base Lys47 may be essential for the reaction.27,28 Similarly, in TEM it has been hypothesized that a neutral Lys73 may exist along the reaction coordinate.29

The conjugate base hypothesis provides a model that can be used to explain the general base/acid catalysis of the whole reaction pathway, with Lys67/Tyr150 playing a central role in the proton transfer of both acylation and deacylation, and Lys67 switching protonation states and conformations along the reaction coordinates. The QM/MM calculations supporting this mechanism considered the formation of the tetrahedral deacylation transition state, during which the proton transfer from the catalytic water to a neutral Tyr150 is coupled to another proton transfer from Tyr150 to a neutral Lys67.7 As a result, in the deacylation transition state, Tyr150 is neutral and Lys67 is charged. The charged state of Lys67 also enables it to act as a general acid to Ser64 in the regeneration of a free enzyme and the release of the product. This is consistent with our observation that Lys67 acts as donors in three hydrogen bonds in the transition state analog structure, including Ser64Oγ, but does require Lys67 to make a switch in hydrogen bond partners: the hydrogen bond between Tyr150 and Lys67 is only observed in the acyl-enzyme complex, and not in either apo or transition state analog structures where Lys67 forms a new hydrogen bond with Ala220O while maintaining those with Ser64Oγ and Asn152Oδ1 throughout the reaction. Therefore, based on the conjugate base hypothesis, the complete proton transfer pathway in the deacylation reaction would be: water → Tyr150 → Lys67 → Ser64. It also implies that in the apo enzyme, Ser64 may act as donor in its hydrogen bond with a neutral Lys67. A reverse proton transfer, Ser64 → Lys67 → Tyr150 → substrate, may therefore be used to explain the general base/acid catalysis in the acylation reaction. This is consistent with the observation that Tyr150Oη is only 3.5 Å away from the β-lactam ring nitrogen in S64G-cephalothin noncovalent complex.5

The conjugate base mechanism and the substrate-assisted catalysis hypothesis are not necessarily mutually exclusive.13,14 Indeed one interpretation of this study is simply that the conjugate-base hypothesis can no longer be discounted by the effect of the Lys67 → Arg substitution, and that both hypotheses are largely consistent with our results and those extant in the field. The ultimate test to differentiate them lies in the direct determination of the pKa values of Lys67 and Tyr150 in the acyl-enzyme complex, assuming that there is one dominant mechanism that holds across most mutants and substrates. This idea underlies most enzymatic studies, and certainly those involving class C β-lactamase, but other alternatives may be imaginable. Thus it is intriguing that the effect of the Lys67 → Arg is substantial but not crippling, especially for deacylation. This and other considerations suggest that the enzyme may be capable of catalyzing the reaction through several distinct pathways and that the choice of a specific mechanism may depend on both the enzyme, that is, mutant or WT, and the substrate. Whereas such a possibility is far from established, it would reconcile the confusion of catalytic mechanisms for class C β-lactamases, and might contribute to their evolutionary robustness.

Methods

Protein purification

K67R AmpC mutant was created using the overlap extension polymerase chain reaction. It was expressed and purified with an m-aminophenylboronic acid affinity column and concentrated using Centricon spin concentrators as described previously.21

Activity assay

The hydrolysis of the β-lactam substrate cephalothin was performed at room temperature in 100 mM Tris.HCl (pH 7.0) with 0.01% Triton X-100. Reaction rates were measured using a Hewlett-Packard HP-8453 spectrometer. Values of Km and kcat were determined by fitting the measurements against the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Crystal growth and data collection

Apo and cocrystals of AmpC K67R mutant were grown using microseeding with hanging drops over 1.7M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 8.7. The initial drops contained 4 mg mL−1 protein; for cocrystals, 500 μM benzo(b)thiophene-2-boronic acid was also included. For cocrystallization, the compound was added to the drop in 5% DMSO and 1.0M potassium phosphate (pH 8.7). Crystals appeared within 5–7 days at 20°C. Before data collection the crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution of 30% sucrose, 1.7M potassium phosphate (pH 8.7) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen after 30 s. Diffraction was measured at Beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source, Berkeley, CA. Reflections were processed using the HKL2000 software package.30

Structure determination and refinement

An apo AmpC structure (pdb ID 1KE4) was used as the initial model and the refinement was performed in CCP4.31 Model rebuilding was carried out in Coot.32 The figures of protein structures were generated by Pymol (Delano Scientific). The structures have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with ID codes 3FKV and 3FKW.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kerim Babaoglu for helpful discussions, and Denise Teotico, Rafaela Ferreira, and Matthew Merski for reading the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Å

Angstrom

- bzb

benzo(b)thiophene-2-boronic acid

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance.

References

- 1.Davies J. Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes. Science. 1994;264:375–382. doi: 10.1126/science.8153624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S. Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity. Chem Rev. 2005;105:395–424. doi: 10.1021/cr030102i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oefner C, D'Arcy A, Daly JJ, Gubernator K, Charnas RL, Heinze I, Hubschwerlen C, Winkler FK. Refined crystal structure of β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii indicates a mechanism for β-lactam hydrolysis. Nature. 1990;343:284–288. doi: 10.1038/343284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galleni M, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Raquet X, Dubus A, Monnaie D, Knox JR, Frere JM. The enigmatic catalytic mechanism of active-site serine β-lactamases. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00502-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beadle BM, Trehan I, Focia P, Shoichet BK. Structural milestones in the pathway of an amide hydrolase: substrate, acyl, and product complexes of cephalothin with AmpC b-lactamase. Structure. 2002;10:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monnaie D, Dubus A, Frere JM. The role of Lysine-67 in a class C ß-lactamase is mainly electrostatic. Biochem J. 1994;302:1–4. doi: 10.1042/bj3020001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gherman BF, Goldberg SD, Cornish VW, Friesner RA. Mixed quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) study of the deacylation reaction in a penicillin binding protein (PBP) versus in a class C β-lactamase. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7652–7664. doi: 10.1021/ja036879a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Minasov G, Roth TA, Prati F, Shoichet BK. The deacylation mechanism of AmpC β-lactamase at ultrahigh resolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2970–2976. doi: 10.1021/ja056806m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukamoto K, Tachibana K, Yamazaki N, Ishii Y, Ujiie K, Nishida N, Sawai T. Role of lysine-67 in the active site of class C β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii GN346. Eur J Biochem. 1990;188:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubus A, Normark S, Kania M, Page MG. The role of tyrosine 150 in catalysis of ß-lactam hydrolysis by AmpC ß-Lactamase from Escherichia coli investigated by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8577–8586. doi: 10.1021/bi00194a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubus A, Ledent P, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Frere JM. The roles of residues Tyr150, Glu272 and His314 in class C ß-Lactamases. Proteins. 1996;25:473–485. doi: 10.1002/prot.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobkovsky E, Billings EM, Moews PC, Rahil J, Pratt RF, Knox JR. Crystallographic structure of a phosphonate derivative of the Enterobacter cloacae P99 cephalosporinase: mechanistic interpretation of a β-lactamase transition-state analog. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6762–6772. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulychev A, Massova I, Miyashita K, Mobashery S. Nuances of mechanisms and their implications for evolution of the versatile β-lactamase activity: from biosynthetic enzymes to drug resistance factors. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7619–7625. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patera A, Blaszczak LC, Shoichet BK. Crystal structures of substrate and inhibitor complexes with AmpC b-lactamase: possible implications for substrate-assisted catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10504–10512. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CC, Rahil J, Pratt RF, Herzberg O. Structure of a phosphonate-inhibited β-lactamase. An analog of the tetrahedral transition state/intermediate of β-lactam hydrolysis. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:165–178. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curley K, Pratt RF. Effectiveness of tetrahedral adducts as transition-state analogs and inhibitors of the class C β-lactamase of Enterobacter cloacae P99. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1529–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers RA, Blazquez J, Weston GS, Morosini MI, Baquero F, Shoichet BK. The complexed structure and antimicrobial activity of a non-β-lactam inhibitor of AmpC β-lactamase. Protein Sci. 1999;8:2330–2337. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.11.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nukaga M, Abe T, Venkatesan AM, Mansour TS, Bonomo RA, Knox JR. Inhibition of class A and class C β-lactamases by penems: crystallographic structures of a novel 1,4-thiazepine intermediate. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13152–13159. doi: 10.1021/bi034986b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato-Toma Y, Ishiguro M. Reaction of Lys-Tyr-Lys triad mimics with benzylpenicillinsight into the role of Tyr150 in class C β-lactamase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1161–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato-Toma Y, Iwashita T, Masuda K, Oyama Y, Ishiguro M. pKa measurements from nuclear magnetic resonance of tyrosine-150 in class C β-lactamase. Biochem J. 2003;371:175–181. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth TA, Minasov G, Morandi S, Prati F, Shoichet BK. Thermodynamic cycle analysis and inhibitor design against β-lactamase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14483–14491. doi: 10.1021/bi035054a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proctor P, Gensmantel NP, Page MI. The chemical reactivity of penicillins and other β-lactam antibiotics. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1982;2:1185–1192. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Soto G, Hirsch KR, Pratt RF. Kinetics and mechanism of the hydrolysis of depsipeptides catalyzed by the β-lactamase of Enterobacter cloacae P99. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3595–3603. doi: 10.1021/bi952106q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matagne A, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Frere JM. Catalytic properties of class A β-lactamases: efficiency and diversity. Biochem J. 1998;330:581–598. doi: 10.1042/bj3300581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powers RA, Shoichet BK. Structure-based approach for binding site identification on AmpC β-lactamase. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3222–3234. doi: 10.1021/jm020002p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.olemi-Kotra D, Meroueh SO, Kim C, Vakulenko SB, Bulychev A, Stemmler AJ, Stemmler TL, Mobashery S. The importance of a critical protonation state and the fate of the catalytic steps in class A β-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34665–34673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313143200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Shi Q, Meroueh SO, Vakulenko SB, Mobashery S. Catalytic mechanism of penicillin-binding protein 5 of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10113–10121. doi: 10.1021/bi700777x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Q, Meroueh SO, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. Investigation of the mechanism of the cell wall DD-carboxypeptidase reaction of penicillin-binding protein 5 of Escherichia coli by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9293–9303. doi: 10.1021/ja801727k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meroueh SO, Fisher JF, Schlegel HB, Mobashery S. Ab initio QM/MM study of class A β-lactamase acylation: dual participation of Glu166 and Lys73 in a concerted base promotion of Ser70. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15397–15407. doi: 10.1021/ja051592u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]