Abstract

MicroRNAs are short non-coding RNAs that function as negative regulators of gene expression. Posttranscriptional regulation by miRNAs is important for many aspects of development, homeostasis and disease. Endothelial cells are key regulators of different aspects of vascular biology including the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis). Here we review the approaches and current experimental evidence for the involvement of miRNAs in the regulation of the angiogenic process and their potential therapeutic applications for vascular diseases associated with abnormal angiogenesis.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, miRNA, endothelial cells, Dicer, gene expression, VEGF, cancer

Introduction

All blood vessels are lined by the vascular endothelium, a critical barrier between the circulating blood and tissue. The non-thrombogenic surface of the endothelium permits the flow of blood to meet the metabolic demands of tissues and alterations in flow patterns are determined by the changes in pressure and vascular resistance in a given vascular segment1. The de novo generation and remodeling of blood vessels is essential to embryonic growth and throughout postnatal life. With regard to the latter, dynamic regulation of vascular density is critical for physiological organ repair during wound healing, post-ischemic tissue restoration and the menstrual cycle. During adulthood, the endothelium remains essentially quiescent, to fulfill their main function to conduct nutritive blood flow to organs, with turnover rates on the orders of months to years and rapid changes in their proliferation rates occur following activation of endothelium by angiogenic cytokines2. The loss of typical endothelial quiescence and barrier function is a common feature of conditions such as inflammation, tumor progression, atherosclerosis, restenosis, and various vasculopathies3.

The formation of the vascular system starts with the assembly of embryonic progenitors cells to form the vascular plexus of small capillaries in a process known as vasculogenesis. This phase is followed by angiogenesis resulting in the expansion of the nascent vascular plexus by sprouting and remodeling into a highly organized and stereotypic network of larger arterial and venous vessels ramifying into smaller ones3,4. Therefore, vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are physiological processes during development that are down-regulated in the healthy adult – except for the organs of the female reproductive system – and are almost exclusively associated with pathology when angiogenesis is induced by microenvironmental factors like hypoxia or inflammation2,5,6. The pathological processes associated with or induced by angiogenesis include diseases as diverse as cancer, macular degeneration, psoriasis, diabetic retinopathy, thrombosis, and inflammatory disorders including arthritis and atherosclerosis. Moreover, insufficient angiogenesis is characteristic of ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease and pre-clampsia3. The above examples represent the broad array of diseases that are associated with the activated endothelial cell (EC) phenotype.

Upon angiogenic activation, EC proliferate, degrade extracellular matrix, change their adhesive properties, migrate, avoid apoptosis, form tube like-structures and eventually mature into new blood vessels. Therefore, the growth of vessels is a complex process involving a number of molecular and cellular events that require to be temporal and spatial orchestrated by a finely tuned balance between stimulatory and inhibitory signals7. Finally, all these processes are controlled by signals received by EC from their microenvironment, signals whose transduction pathways lead specific programs of gene expression to assure an adequate angiogenic response8,9.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as crucial players regulating the magnitude of gene expression in a variety of organisms10. This class of short (≈ 22 nucleotides) non-coding RNA molecules have been shown to participate in almost every cellular process investigated so far11, and their dysregulation is observed in -and might underlie- different human pathologies including cancer, heart disease and neurodegeneration12-15. These new molecular regulators have been identified in ECs and their role in the regulation of different aspects of the angiogenic process has been recently investigated in a variety of laboratories16-22. The present review focuses on the approaches and current experimental evidence for the involvement of miRNAs in the angiogenic process and their potential therapeutic applications for vascular diseases associated with abnormal angiogenesis.

miRNAs: biogenesis and modus operandi

Since the discovery of the first two miRNAs -lin-4 and let-723-25 hundreds of miRNAs have been identified in plants, animals and viruses by molecular cloning and bioinformatics approaches26. miRNAs constitute a family of short non-coding RNA molecules of 20-25 nucleotides in length that regulate gene expression at the post-trancriptional level27,28. They generally repress target mRNAs through an antisense mechanism. In animals, miRNAs typically target sequences in the transcript 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTR) that are only partially complementary to the miRNA, causing a repression of the protein synthesis29. They are involved in the control of a wide range of biological functions and processes such as development, differentiation, metabolism, growth, proliferation and apoptosis11,12,14,27,28,30 and are the center of attention in molecular and cell biology research. More than 700 human miRNAs have been cloned and bioinformatic predictions indicate that mammalian miRNAs can regulate approximately 30% of all protein-coding genes29,31.

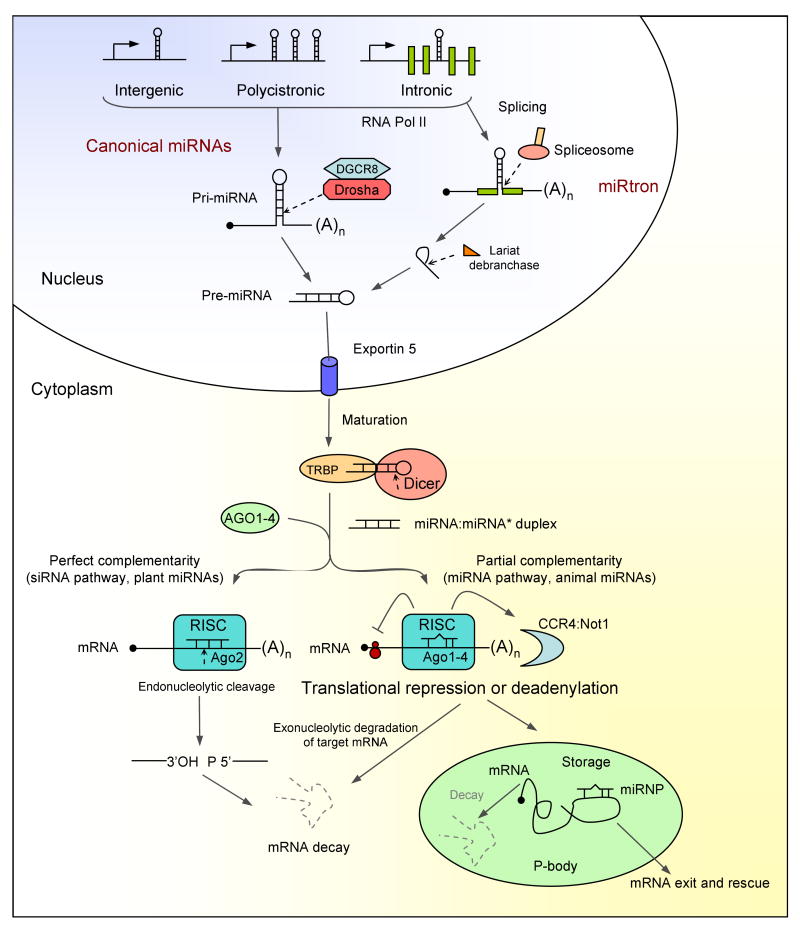

Most miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from individual miRNAs genes, from introns of protein coding genes, or from polycistronic transcripts that often encode multiple related miRNAs32. These long –thousands of nucleotides- primary transcripts generate a stem-loop containing primary miRNA (pri-miRNA). The pri-miRNA is processed within the nucleus by a ribonuclease III (RNase III), called Drosha33, along with an RNA-binding protein DGCR8/Pasha34 (Figure 1). Most mammalian miRNAs that are encoded in introns are processed before splicing, however there is a subset of intronic miRNAs called “miRtrons” that circumvent the Drosha pathway35. The product of the Drosha cleavage event is a 70-100 nucleotides hairpin-shaped precursor (pre-miRNA) that is transported to the cytoplasm via an Exportin-5 and Ran-GTP dependent mechanism36. Then the pre-miRNA is further cleaved to produce the mature ≈ 22-nt miRNA:miRNA* duplex by another RNaseIII enzyme, Dicer37 (Figure 1). The miRNA duplex is incorporated into the effector ribonucleoprotein complex RISC (RNA induced silencing complex)38,39 whose key components are proteins of the Argonaute (AGO) family40 (Figure 1). The miRNA duplex is unwound into the mature single-stranded form (guide strand) and its complementary strand (passenger strand or miRNA*) that is typically degraded. The stem loop in pre-miRNAs contributes to the strand selection, however the miRNA* also has chance to be selected and used in gene regulation41. As part of the RISC, the miRNA guides the complex to its RNA targets by Watson-Crick base-pairing interactions. In cases of perfect or near-perfect complementary to the miRNA, target mRNA 3′UTR can be cleaved and degraded. In most cases, animal miRNAs pair imperfectly with their targets and their translation is repressed42. The mechanism(s) of translational repression by miRNAs remains unclear and can also affect mRNA stability. These include sequestration from ribosomes (by relocation into P bodies), blockage of translational initiation, translational repression after initiation and target deadenylation coupled to transcript degradation42,43 (Figure 1). Recent reviews covering these topics and more general information about biogenesis and mechanisms of action can be found11,12,29,44.

Figure 1. miRNA biogenesis and function.

miRNAs are originate in the nucleus as RNA polymerase II primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs), which are transcribed from independent miRNA genes, from polycistronic transcripts or from introns of protein-coding genes. Pri-miRNAs are then processed in two steps, catalyzed by the RNase III type endonuclease Drosha and Dicer. These enzymes function in complexes with dsRNA-binding domains proteins, DGCR8 and TRBP for Drosha and Dicer, respectively. Drosha-DGCR8 processes pri-miRNAs to ≈ 70 nucleotides hairpins known as pre-miRNAs. A subset of miRNAs, called miRtrons, also derived from introns, is processed into pre-miRNAs by the spliceosome and the debranching enzyme. Both canonical miRNAs and miRtrons are exported to the cytoplasm via Exportin 5, where they are further processed by Dicer-TRBP to yield ≈ 20-bp miRNA duplexes. One strand is selected to function as mature miRNA and loaded into the RISC, while the partner miRNA* strand is preferentially degraded. The mature miRNA leads to translational repression or mRNA degradation. The key components of the RISC are components of the Argonaute family (Ago 1-4). A fraction of miRNA* species can also access Ago complex and regulate targets. Perfect complementarity between miRNA and mRNA leads to an endonucleolytic cleavage, catalyzed by the human Ago2 in the RISC. This mechanism applies to siRNAs and many plant miRNAs. Animal miRNAs usually show only partial complementarity to the target mRNA promoting translational repression (initiation and post initiation steps) or deadenilation coupled to exonucleolytic degradation of target mRNA. mRNAs repressed by deadenylation or at the translation-initiation step are moved to P-bodies for either degradation or storage.

Elucidation of the function of a miRNA requires identification of putative mRNA targets that it regulates and this is very challenging since miRNA usually are imperfectly complementary to their targets. In mammals, the most consistent requirement, although not always essential, of miRNA:target interaction is a contiguous and perfect base pairing of the miRNA nucleotides 2-8, representing the “seed” region. In many cases, the seed seems to determine this recognition; in other cases, additional determinants are required, such as reasonable complementarity to the miRNA 3′ half to stabilize the interaction, mismatches must to be present in the central region of the miRNA-mRNA, among others12,29,45,46. It is important to note that identifying functionally important miRNAs targets is crucial for understanding miRNA functions. However, the possibility that a single miRNA may target multiple transcripts within a cell type and that individual transcripts may be subject to regulation by multiple miRNAs amplifies the scope of putative miRNA regulation of gene expression, and indicates that the particular cellular context of a given miRNA will determine its function in a specific cell type.

Regulation of Angiogenesis by miRNAs: global approaches

An approach to examine the spectrum of the biological significance of miRNAs is to remove all miRNAs by mutation or disruption of Dicer, the rate limiting enzyme involved in the maturation of miRNAs. Dicer loss of function results in profound developmental defects in both zebrafish and mice47,48. Zebrafish lacking Dicer undergo to a relative normal morphogenesis and organ development but die two weeks after fertilization due to a general growth arrest48. The survival to this stage likely reflects the presence of maternal Dicer. When an offspring of fish that lack both maternal and zygotic Dicer was created49, these Dicer-null embryos exhibited severe defects most prominently in gastrulation, brain morphogenesis, cardiac development associated with a disrupted blood circulation. Reminiscent of the zebrafish dicer-null phenotype, loss of Dicer in mice by replacement of exon 21 with a neomycin-resistance cassette leads to lethality early in embryogenesis at day 7.5 and the embryos were depleted of pluripotent stem cells47. Another group generated Dicerex1/2 mice have a deletion of the amino acid sequences from the first two exons of the Dicer gene50. Dicerex1/2 homozygous embryos die between days 12.5 and 14.5 of gestation, again demonstrating that Dicer is necessary for normal mouse development. To further explore the consequences of Dicer deletion, several laboratories have generated mice harboring conditional Dicer alleles. Tissue-specific inactivation of Dicer has led to the conclusion that Dicer is essential for proper limb formation, lung and skin morphogenesis, the maintenance of hair follicles, T cell development, differentiation and function, neuronal survival, skeletal muscle development, chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, germ cell development and spermatogenesis, autoimmunity and antibody diversity and B lymphocytic lineage survival51-64. At the level of the cardiovascular system, cardiac specific deletion of Dicer produces dilated cardiomyopathy associated with heart failure in neonates65 and spontaneous cardiac remodeling when Dicer deletion was induced postnatally in the myocardium66.

Recent reports, both in vitro and in vivo, also indicate a role for Dicer-dependent miRNAs in vascular signaling and functions related to angiogenesis16,19,20,50,67. In fact, the early embryonic lethality observed in Dicerex1/2 mice has been suggested to be a consequence of defective blood vessel formation and maintenance50, data that were in accordance with the disrupted blood circulation observed in zebrafish Dicer-null embryos49. The defects observed in Dicerex1/2 embryos and yolk sacs were associated with altered expression of vascular endothelial growth facto (VEGF), its receptors KDR (VEGFR2) and FLT-1 (VEGFR1) as well as the putative angiopoietin-2 receptor, Tie-1. This study suggests that Dicer has a role in embryonic angiogenesis, probably through processing of miRNAs that regulate expression levels of key angiogenic regulators50. These observations give rise for a series of studies relating to miRNA and endothelial cells functions relevant to angiogenesis.

The functional role of miRNAs in endothelial cells was assessed by specifically silencing Dicer using short interfering RNA (siRNA) in human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) and EA.hy.926 cells. Depletion of Dicer impairs the development of capillary-like structures and exerts an antiproliferative effect16,19,20. The knockdown of Dicer in human microvascular endothelial cell (HMECs) shows diminished tube formation and cell migration67. Accordingly, migration was also impaired in Dicer knockdown HUVECs when fibronectin was used as matrix16. As expected, the knockdown of Dicer in EC alters constitutive protein expression patterns, largely affecting proteins that play a role in endothelial cell biology and angiogenic responses, such us Tie-2/TEK, VEGFR2, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), IL-8 and angiopoietin like 4 (ANGPTL4)19. Some of the upregulated transcripts/protein were consistent with the reported Dicerex1/2 embryos, such as of Tie-2/TEK and VEGFR219,50. The decrease in growth and morphogenesis observed in EC after Dicer silencing16,19,20 was consistent impaired vascular development in Dicerex1/2 embryos and regardless of the paradoxical upregulation of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 observed in Dicerex1/2 embryos50 and VEGFR1, VEGFR2, Tie-2 and eNOS observed in Dicer knockdown ECs19. Interestingly, the Dicer silencing in EC increased the expression of thrombospondin-1 (Tsp1)16,20, a multi-domain matrix glycoprotein that has been shown to be a natural endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, which may explain, in part, the antiangiogenic phenotypes observed in vitro. Furthermore, the knockdown of Dicer in HMECs also reduces the expression of miRNAs that control the expression of the HMG-box protein 1 (HBP1) transcriptional suppressor, which negatively regulates p47phox of the NADPH oxidase complex, decreases the basal production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) impairing aspects of redox regulation during an angiogenic response67.

The early embryonic lethality of Dicer null alleles in mice47, 50 has limited the ability to address the role of Dicer in normal mouse growth and development. The global effect of Dicer deficiency in adult mice was investigated by using a Dicer hypomorphic mouse (Dicerd/d), obtained by a gene-trap method68. Dicerd/d female mice are infertile due to corpus luteum (CL) insufficiency and defective ovarian angiogenesis. CL is formed from the ovulated follicle and plays a critical role in the secretion of progesterone, a hormone needed for the maintenance of early pregnancy and requires intense angiogenesis. Impaired CL angiogenesis was partly explained by the lack of miR-17-5p and let7b, miRNAs that participate in angiogenesis via targeting the anti-angiogenic factor tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1)69. Although CL angiogenesis was reduced, embryonic vasculogenesis and angiogenesis were not affected in Dicerd/d mice, indicating that angiogenesis in different tissues has different sensitivities to the levels of Dicer protein68,69.

The first attempt to show the role of endothelial miRNAs in angiogenesis in vivo was performed by subcutaneous injection of Dicer knockdown HUVEC (suspended in a matrigel plug) into nude mice, demonstrating reduced sprout formation16. Finally, the requirement of endothelial miRNAs for post-natal angiogenesis was recently tested by the generation of two EC-specific Dicer knockout mouse lines, conditional Tie2-Cre;Dicerflox/flox mice and the tamoxifen (TMX) inducible VECad-Cre-ERT2;Dicerflox/flox mice20. Despite the fact that Dicer protein was reduced and miRNA production diminished (e.g. miR-126 and miR-31) in EC isolated from Tie2-Cre;Dicerflox/flox mice, they were viable and overtly normal, suggesting the mice were hypomorphic for Dicer expression in the endothelium. However, the lack of lethality allowed investigation of the relevance of endothelial miRNAs in post-natal angiogenic responses using several models of angiogenesis. VEGF (VEGF-A) is a major pro-angiogenic factor whose main functions are to promote EC survival, induce EC proliferation, enhance cell migration and invasion of EC, all phenotypes that promote angiogenesis. As shown previously in human EC transfected with Dicer siRNA16,19 VEGF driven angiogenesis is reduced in mice that are conditional EC-specific Dicer hypomorphs20. Altered miRNA expression has been implicated in tumor formation via miRNA modulation of critical genes involved in tumor cells proliferation or survival14,70. Importantly, angiogenesis is necessary for adequate delivery of nutrients and oxygen to growing tumors71. Interestingly, the participation of endothelial miRNAs in the tumor-induced neovascularization, was examined by post-natal inactivation of Dicer in the endothelium prior to tumor implantation. Tumor growth as well as the tumor-induced microvessel formation was reduced in VECad-Cre-ERT2;Dicerflox/flox 20. Taken together, miRNAs participate and are required for tumor cell proliferation plus angiogenesis. The pathophysiological relevance of endothelial miRNAs was also further investigated in response to limb ischemia and wound healing20. The vascular supply to limbs and peripheral tissues is essential for normal physiological functions. Under certain pathologic conditions, however, vascular supply may be reduced to such an extent that it leads to necrosis of the tissue. After ischemia, inactivation of Dicer in EC reduced the angiogenic response to limb ischemia indicated by a reduction in capillary densities and blood flow recovery. The reduced flow impaired lower limb function and resulted in higher ischemic damage scores20. Recent works on the significance of miRNA in skin morphogenesis and development provide important insight that lays the foundation for wound healing process53,54, the potential significance of miRNAs in cutaneous wound angiogenesis has also been discussed72. As mentioned before, angiogenesis is necessary for wound repair since the new vessels provide nutrients to support the active cells, promote granulation tissue formation and facilitate the clearance of debris. Cutaneous wound-healing was delayed when Dicer was inactivated in EC. Tie2-Cre;Dicerflox/flox and post-natally in VECad-Cre-ERT2;Dicerflox/flox showing larger areas of granulation tissue devoid of hair follicles with less granulation tissue deposition and collagen accumulation20, hallmarks of an angiogenic response.

The knockdown of Drosha –involved in the processing of pri-miRNAs- was also undertaken to globally reduce miRNAs. The silencing of Drosha in EC produces less pronounced effects on angiogenesis than Dicer silencing16,19, although capillary sprouting and tube forming activity were blunted; the knockdown of Drosha does not exert significant effects on the in vivo matrigel plug model16. This may be explained by the processing of pri-miRNA independent of Drosha35. On the other hand, the angiogenic potential of EC disappeared when Ago2 –component of the RISC- was knockdown73. Of the four mammalian Argonautes (Ago1-4), only Ago2 functions in the RNA interference pathway74,75, whereas all four seem to participate in the miRNA-mediated repression, indicating that the global impairment of repression by impeding miRNA-mRNA interaction also affect EC angiogenic responses.

These experimental approaches likely reveal the consequences of a block in miRNA biogenesis, however it is important to consider when interpreting the data, the fact that Dicer may participate in other processes unrelated to miRNA biology, such as formation of the heterochromatin76 and that there are alternative Drosha-independent pri-miRNA processing pathways35. Deciphering the miRNA network responsible for the modulation of the angiogenesis might lead to novel therapeutic approaches for cancer, wound healing and ischemic conditions such myocardial ischemia, peripheral vascular disease and vascular diabetic complications.

Role of individual miRNA in angiogenesis

Although the previous studies emphasize the importance of the miRNA pathway in several aspects of the angiogenic process, the majority does not provide information regarding the functions of specific miRNAs. Studies aimed at elucidating the role of individual miRNAs in the regulation of angiogenesis are increasingly being performed and most of the examples that illustrate principles of miRNA function in angiogenesis are presented here.

Many miRNAs exhibit striking organ specific expression patterns suggesting cell type-specific functions77-79. Consequently, dysregulation of miRNA expression and function may lead to human diseases12. The first large-scale analysis of miRNA expression in EC was carried out in HUVECs and identified 15 highly expressed miRNAs with receptors of angiogenic factors (Flt-1, Nrp-2, Fgf-R, c-Met as c-kit) as putative mRNA targets, according to prediction algorithms18. Additional studies also profiled the expression of miRNAs in ECs16,19. The highly expressed miRNAs that were common in at least two out of the three studies, included miR -15b, -16, -20, -21, -23a and b, -24, -29a and b, -31, -99a, -100, -103, -106, 125a and b, -126, -130a, -181a, -191, -221, -222, -320, -let-7, let-7b, let-7c and let-7d16,18,19. However, their specific targets and functions in EC related to angiogenesis has only been characterized for a few of them (Table 1).

Table 1. Compilation of miRNAs associated with angiogenesis.

| miRNA | Cell type | miRNA target(s) (direct or indirect*) | Function (by miRNA overexpression or inhibition) and putative role in angiogenesis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-221 miR-222 |

EC (HUVECs, EAhy 296) Prostate cancer cell lines |

c-kit, eNOS* p27/Kip1 |

Overexpression reduces tube formation, migration and wound healing (scratch assay) in response to SCF. ↓EC-mediated angiogenesis Induce proliferation and cell cycle progression. Inhibition reduces proliferation, increase p27 and reduces clonogenity of cells. ↑Tumor induced angiogenesis |

18, 19 84 |

| let-7f miR-27b |

EC (HUVECs) | ND | Inhibition reduces in vitro sprout formation ↑EC-mediated angiogenesis |

16 |

| miR-126 | EC (HUVECs, HAEC, mouse ECs) | Spred-1, PIK3R2/p85-β, VCAM-1 | Inhibition increases TNF-induced expressionof VCAM-1 and leukocyte adhesion to ECs Regulates vascular integrity and angiogenesis in miR-126 knockdow zebrafish and miR-126-/- mice. Inhibition reduces tube formation, sprout formation, wound healing (scratch assay) and proliferation in response to VEGF and FGF. ↑EC-mediated angiogenesis |

17, 22, 85 |

| miR-130a | EC (HUVECs) | GAX, HOXA5 | Overexpression antagonized the inhibitory effect of GAX on EC proliferation, migration and tube formation and the inhibitory effects of HoxA5 on tube formation ↑EC-mediated angiogenesis |

107 |

| miR-210 | EC (HUVECs) Breast and colon cancer cell lines, nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line, head and squamous cell carcinoma |

EphrinA3 ND |

Stimulated by hypoxia. Overexpression stimulates tube formation and migration. ↑EC-mediated angiogenesis Stimulated by hypoxia. decrease proapoptotic signaling in a hypoxic environment. ↑Tumor induced angiogenesis |

108 110, 111 |

| miR-15 miR-16 |

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) Colon cancer cells | VEGF, Bcl2 | Downregulated by hypoxia. Overexpression induces apoptosis in leukemic cell line model. Cell cycle regulation. Inhibition reduces number of cells G0/G1 promoting cell cycle progression. ↓Tumor induced angiogenesis |

111, 115, 116 |

| miR-378 | Glioblastoma cells | Sufu, Fus-1 | Overexpression promotes cell survival tumur growth and angiogenesis in vivo. ↑Tumor induced angiogenesis | 140 |

| miR-17-92 cluster | EC (HUVECs) Malignant lymphoma cells, Colorectal cancer cells, NSCLC Lymphocytes |

Tsp-1 (miR-18a) E2F1 (miR-17-5p / miR-20a) CTGF (miR-18a, Tsp-1 (miR-19) PTEN, Bim |

Stimulated by VEGF. Overexpression promotes cell proliferation and cord formation converse effects by inhibition. ↑EC-mediated angiogenesis Expression control by c-Myc and E2F. Promote cell proliferation and survival. Overexpression in colonocytes form larger and better-perfused tumors in vivo. ↑Tumor induced angiogenesis Overexpression contributes lymphoproliferative disease. |

20 101, 120, 122, 123 127 |

| miR-296 | EC (human brain microvascular ECs) | HGS | Stimulated by glioma cells and angiogenic factors (EGF, VEGF). Inhibition reduces tube formation and migration (scratch assay) in vitro and angiogenesis in tumor xenografts in vivo. ↑EC-mediated and tumor induced angiogenesis | 109 |

| miR-155 | EC, VSMC, Fibroblast Breast cancer cells, malignant lymphoma cells, NSCLC Lymphocytes, macrophages |

AT1R ND ND |

Inhibtion increases AT1R expression and Ang II-induced ERK1/2 activation. ?EC-mediated angiogenesis Required for normal immune and imflammatory responses |

95, 141 97, 121, 122,142, 143 |

ND= not determined

The prediction algorithms utilized to find receptors for angiogenic factors that may potentially be targeted by some of the miRNAs identified miR-221 and miR-222 to target c-kit18. c-kit is a tyrosine kinase receptor for stem-cell factor (SCF), and has been shown to promote survival, migration and capillary tube formation in HUVECs80. Interestingly, transfection of HUVECs with miR-221/222 inhibits tube formation, migration and wound healing in response to SCF18. miR221/222 were shown to control the growth of erythropeitic and erythroleukemic cells, through the regulation of c-kit expression at translational level81. Accumulating evidence suggests that bone marrow–derived circulating precursors contribute to vascular repair, remodeling, and lesion formation under physiological and pathological conditions82. Interestingly, the interaction between miR-221/222 and the c-kit 3′UTR was also demonstrated in ECs and thus the antiangiogenic activity of these miRNAs18. miR221/222 overexpression in Dicer knockdown ECs restored the elevated eNOS protein levels eNOS induced by after Dicer silencing19. NO synthesized by eNOS is necessary for EC survival migration and angiogenesis83. However, prediction sites for these miRNA were not found in eNOS 3′ UTR, suggesting that the regulation of eNOS protein levels by miR-221/222 is likely to be indirect. Collectively, these reports suggest an antiagiogenic action for these miRNAs and then might be a potential tool to block angiogenesis. However, it is important to note that miR221/222 can also promote cancer cell proliferation through the regulation of p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor84, indicating that the regulation of proliferation by these miRNAs appears cell type specific. Therefore, cell specific targeting with miRNAs is an important area of investigation to be developed.

Other miRNAs expressed in EC, let-7f and miR-27b, have been shown to exert pro-angiogenic effects, as revealed by the blokade of in vitro angiogenesis with 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides inhibitors16, although their targets in ECs have not been already characterized.

The best characterized EC-specific miRNA is miR-12617,22,85. miR-126 is a highly conserved miRNA (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/index.shtml). In both mouse and zebrafish miR-126 is enriched in tissues with a high vascular component such as the lung and the heart86,87. In mammals, it is encoded by intron 7 of the EGF-like domain 7 (Egfl7) gene also known as VE-statin, which encodes an EC-specific secreted peptide that acts as a chemoattractant and inhibitor of smooth muscle cell migration88,89. Location of miRNAs within non-coding regions of specific genes represents a common mechanism of co-regulation. Although the intronic miRNAs and their host genes could be regulated independently, it is possible that the signals that activate the transcription of the host gene lead to the transcription of the intronic miRNA. These miRNAs can in turn mediate the regulation of its host protein-coding gene or the regulation of other proteins whose expression is inappropriate for the stimulated process. In this regard, miR-208, is a cardiac specific miRNA encoded by an intron in the gene that encodes α-myosin heavy chain and function within a regulatory network to control cardiac stress response79. Thus, the expression pattern of miR-126 in tissues and cells lines22 parallels to of Egfl790,91. Additionally, miR-126 has been shown to be enriched in embryonic bodies-derived Flk1 positive cells. Indeed, the expression of Egfl7 and miR-126 largely matched that of EC markers during embryoid body formation, being highly enriched in Flk1-positive vascular progenitors at d4 as well as in mature CD31- expressing ECs at d717. Although enriched in vascular progenitors, it is not sufficient to promote the differentiation of pluripotent cells towards an EC lineage17. In vitro, miR-126 regulates many aspects of EC biology, including cell migration, organization of the cytoskeleton, capillary network stability and cell survival17. In vivo, the knockdown of miR-126 in zebrafish resulted in the loss of vascular integrity and hemorrhage during embryonic development17. Futhermore, targeted deletion of miR-126 in mice causes partial embryonic or perinatal lethality (40% of miR-126−/− mice). The embryonic lethality was due to a severe systemic edema, multifocal hemorrhages and rupture of blood vessels. Of the miR-126−/− mice that survived to birth, 12% died by P1 and contained excessive protein rich fluid in the pleural space of the thoracic cavity, indicating a severe edema. The surviving miR-126−/− mice appeared normal to adulthood and displayed no obvious abnormalities22, indicating that miR-126 plays an important role in the maintenance of vascular integrity during embryogenesis but not for vascular homeostasis after birth. Interestingly, ECs from adult miR-126−/− mice showed diminished angiogenic responses, suggesting a role for miR-126 in neoangiogenesis of adult tissues in response to injury. Indeed, when miR-126−/− where subjected to myocardial infarction, 50% died after 1 week and nearly all of them die by 3 weeks, in contrast, 70% of wild type (wt) mice survive at least for 3 weeks22. In fact, PECAM staining revealed extensive vascularization in the injured myocardium of wt mice, whereas there it was reduced in miR-126−/− mice22. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) was the first target identified for repression by miR-126 in vitro85, however additional targets have been identified17,22. Gene expression profiles by microarray analysis of EC isolated from adult kidneys of wt and miR-126−/− mice22 or from miR-126 zebrafish morphants or from HUVECs in which miR-126 was knockdown17 were performed to identify genes regulated by miR-126. Genes implicated in endothelial cell biology, angiogenesis, cell cycle, inflammation, cytoskeleton and growth factors were dysregulated in the absence of miR-12617,22. Bioinformatic analysis, predicted integrin α-6, VCAM-1 and Sprouty-related protein-1 (Spred-1)17,22 as well as phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 2 (PIK3R2) also known as p85-β, regulator of G protein signaling 3 (RGS3) and CRK17. miR-126 directly targets the 3′ UTR of Spred-117,22, VCAM-117,85 and PIK3R217 for repression. Spred-1 and PIK3R2 have been shown to function as negative regulators of VEGF / FGF signaling via MAP-kinase and PI3 kinase pathways, respectively. Thus, miR-126 promotes growth factor (VEGF/FGF) signaling, angiogenesis and vascular integrity by inhibiting endogenous repressors of growth factors within ECs17,22. This findings illustrate that a single miRNA can regulate vascular integrity and angiogenesis, providing a new target for either pro- or antiangiogenic therapies.

As mentioned before, numerous factors are implicated in vessel growth. Among these factors, angiotensin II (Ang II), the main effector peptide of the renin-angiotensin system, appears to be implicated in the regulation of the angiogenic process92. ANG II has been shown to work through both type 1 (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptors, which display opposing vasomotor and angiogenic actions93. AT1R receptor activation is known to stimulate vascular growth and microvascular angiogenesis in nonneural tissues such as skeletal and cardiac muscle, whereas AT2R activation was recently shown to antagonize these actions94. miR-155 is expressed in ECs and VSMC20,95 and has been shown to specifically interacts with the 3′UTR of the human AT1R mRNA, thereby reducing the endogenous expression of the hAT1R and consequently Ang II signaling95. Translational repression by miR-155 provides yet another mechanism by which AT1R expression can be modulated. In this regard, it has been reported that Ang II induces in a dose dependent manner the expression VEGFR2 and significantly enhances VEGF-induced cell proliferation and tube formation, mediated by AT1 receptor96 and suggesting that AT1 receptor may contribute to the development of diabetic retinopathy by enhancing VEGF-induced angiogenic activity. Then, the downregulation of AT1R by miR-155 suggest an antiangiogenic function for this miRNA in ECs. However, its role in EC angiogenesis has not been specifically addressed. Stimulation of human fibroblast with transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF-β1) decreased the expression of miR-155 and increased the expression of hAT1R. Furthermore, miR-155 is induced in macrophages by cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α) and interferon β (IFNβ)97. Interestingly, angiogenic stimulation of EC with VEGF increases the expression of miR-15520 suggesting VEGF may control the levels of ATR1 via miR-155. Nevertheless, the oncogenic potential of miR-155 has been confirmed in mice, where its overproduction leads to spontaneous B-cell malignancy, showing the complexity of miRNA-mediated regulation, given that the same miRNA may have opposite effects in different biological contexts.

Regulation of miRNA expression in angiogenesis

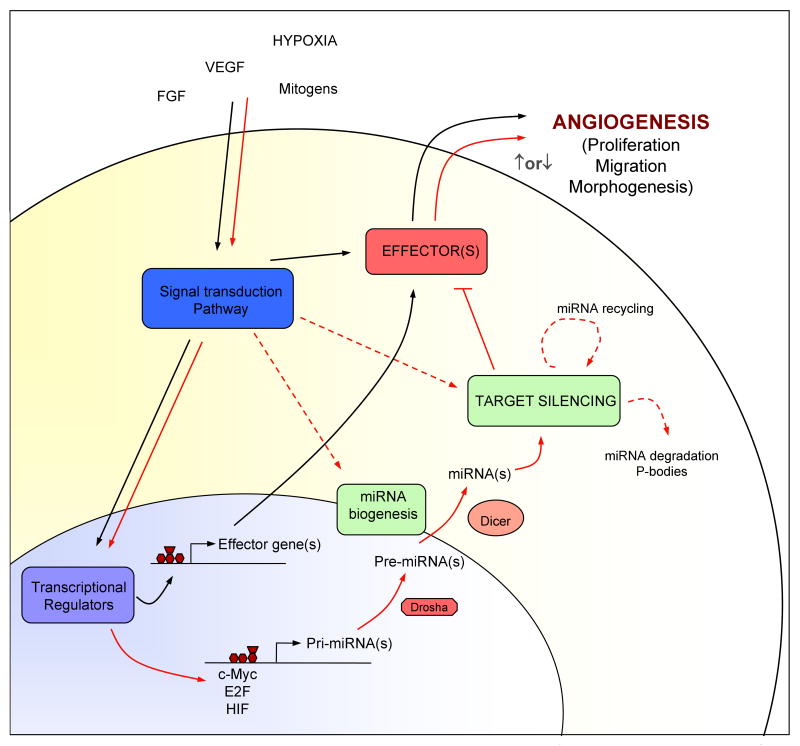

It is well accepted that miRNAs post-transcriptionally govern the levels of gene expression. However an important burgeoning area of investigation is to elucidate how the levels of miRNAs, per se, are regulated. The information about specific regulation of miRNAs has comparatively lagged behind, in contrast to the wealth of publications about their biological effects. Indeed, extracellular factors can modify the activity of a miRNA by affecting its expression, stability (by controlling synthesis or degradation or cellular localization98-102. In this regard, promoter elements that could contribute to the expression of the muscle-specific miR-1/miR-133 cluster have been identified103 as well as the implicated in miR-223 during granulopoiesis98. The oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc activates the miR-17-92 cluster, and this mechanism plays an important role in tumor formation101. Furthermore, LPS treatment of human monocytes induced the expression of miR-146, -142 and -155 as determined by miRNA microarrays and that miR-146 was induced in an NFkB-dependent manner97,104. These exciting studies raise the possibility that extracellular signals via Toll like receptors (TLR) modulate the expression of key miRNAs which then regulated the levels of genes necessary for TLR dependent functions. This concept of miRNA regulation has been extended to the cytokine IFNβ, which induces key miRNAs that aid in combating viral infections105. More recently, miRNA profiling of TGF-β or bone morphogenic protein (BMP) treated human vascular smooth muscle cells revealed that TGF-β/BMP induces the expression of miR-21 leading to an upregulation of genes necessary for the contractile phenotype. The mechanism of miR-21 induction is quite novel, where TGF-β enhances the processing of pri-miR-21 into pre-miR-21 by regulating the miRNA processing enzyme Drosha106. Accordingly, extracellular signals can modify the levels of a miRNA and thereby its activity providing a mechanism to regulate the robustness of an integrated functional response such as an angiogenic response (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Function and regulation of miRNAs in angiogenesis.

The schematic illustrate how stimuli such as FGF, VEGF, hypoxia or mitogens promote angiogenic phenotypes (black lines) and the potential role of how miRNAs may participate in this process (red lines). Extracellular signals activate signal transduction pathways that lead to an angiogenic response by direct activation of the specific effectors (MAPK, Akt, etc) or by induction of gene expression. In turn, the activation of the signal transduction pathways can modify the activity of a miRNA by affecting its expression, biogenesis and degradation (red dashed lines). miRNA-mediated regulation of angiogenic effectors promotes fine-tuning modulation of angiogenic responses via modulation of key effectors that promote angiogenic phenotypes such as proliferation, migration and/or morphogenesis.

Recent studies investigated the regulation of miRNAs in EC in response to serum, hypoxia, VEGF and tumor-derived growth factors20,107-109.

miR-130a is expressed at low levels in quiescent HUVECs and is upregulated in response to fetal bovine serum107. miR-130a is a regulator of the angiogenic phenotype of EC through to is ability to modulate the expression of the antiangiogenic homeobox proteins GAX (growth arrest homeobox) and HoxA5. miR-130a antagonizes the inhibitory effect of GAX on EC proliferation, migration and tube formation and the inhibitory effects of HoxA5 on tube formation107. The regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia is an important component of homeostatic mechanisms that link vascular oxygen supply to metabolic demand5.

Hypoxia occurs during several pathophysiological circumstances (e.g. tumor development, chronic ischemia). In cancer cells a set of hypoxia-regulated miRNAs have been identified110-112, supporting a key role of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) as a transcription factor for miRNA expression during hypoxia100, however only few miRNAs promoters have been identified experimentally113,114. Hypoxia induces the expression of different growth factors including VEGF, an important angiogenic factor. For this gene, a group of candidate regulatory miRNAs has been identified recently and the miRNA-regulation of VEGF under hypoxia was investigated in cancer cells111. Interestingly, most of the miRNAs that were predicted to target VEGF were found to respond to hypoxia, which could lead to an extra layer of complexity in the angiogenic response. miR-15 and -16 regulate VEGF expression but are downregulated by hypoxia111. Interestingly, these miRNAs have been shown to induce apoptosis in leukemic cells by targeting the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2115, block cell cycle progression116 and are frequently down-regulated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia117. Regarding to EC, miR-210 is induced by hypoxia108. Overexpression of miR-210 in normoxic EC stimulates the formation of capillary-like structures and VEGF-driven migration, whereas its blockade inhibits the formation of the capillary-like structures and decreases the migration in response to VEGF. The relevant target for miR-210 in hypoxia was Ephrin-A3 (Eph-A3). Ephrin ligands and their receptors have been shown to play a crucial role in the development of the cardiovascular system. Although the importance of EphA2 in the regulation of angiogenesis and VEGF signaling has been reported, little is known yet about the specific role of Eph-A3. However, this data suggests that down-regulation of Eph-A3 is necessary for the miR-210-mediated stimulation of capillary-like formation and EC chemotaxis in response to VEGF and may contribute to modulate the angiogenic response to ischemia.

The modulation of the expression of EC-miRNAs by VEGF has been recently investigated20. VEGF treatment of HUVECs regulated the levels of several miRNAs, among them hsa-miR-191, -155, -31, -17, -18a, -20a, whose expression was increased, however little change was observed in the expression of hsa-miR-126 and -22220. The first set of miRNAs are commonly overexpressed in human tumors and have been implicated in the control of tumor growth, survival and angiogenesis118-122. Transcription factors c-myc and E2F control the expression of the miR-17-92 cluster including miR-17, -18a, -20 and miR-19a, -19b and -92a101,123,124. Interestingly, VEGF has been shown promote proliferation of cortical neurons precursors by regulating E2F expression125. E2F1, E2F2 and E2F3 are involved in the regulation of apoptosis and cell proliferation126. Components of this cluster target the expression of E2F1 and target the expression of E2F1 promoting proliferation by shifting the E2F transcriptional balance away from the pro-apoptotic E2F1 and toward the proliferative E2F3 transcription network101,124. Since the levels of miR-17, -18a and 20a in quiescent EC were very low, VEGF induction of these miRNAs suggest that they may regulate the proliferative actions of VEGF. In fact, overexpression of these miRNAs in Dicer knockdown EC rescues the defect in cell proliferation and cord formation20 suggesting that VEGF-induced proliferation and morphogenesis are mediated in part by miR-17-92 activation. When components of this cluster are overexpressed in tumors cells (Kras-transformed mouse colonocytes) they specifically target anti-angiogenic proteins containing thrombospondin type 1 repeats such as Tsp1, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and SPARC120. In particular, miR-18 preferentially suppresses CTGF expression, whereas miR-19 targets Tsp1. By using MiRanda algorithm both miR-18 and -19 are predicted to target Tsp1 (depending on species). In human EC, miR-18a preferentially targets Tsp120. When EC were transfected with the components of miR-17-92 cluster upregulated by VEGF, miR-18a reduces basal levels of Tsp1 expression. Moreover, increased Tsp1 levels by Dicer silencing16,20 were restored to control levels by expression of miR-18a20. Collectively, this data indicate that VEGF modulation of miRNAs, specifically components of the miR-17-92 cluster, may participate in the control of angiogenic phenotypes in EC. Furthermore, miR-17-92 miRNAs suppress the expression of the tumor suppressor PTEN and the proapoptotic protein Bim, contributing to the lymphoproliferative disease of miR-17-92-transgenic mice and contributing to lymphoma development in patients with amplifications of the miR-17-92 region127. Moreover, deletion of this locus in mice resulted in smaller embryos and immediate postnatal death128.

Finally, a recent report show that glioma- or growth factor-mediated the induction of miR-296 in primary human brain microvascular EC as well as in primary tumor EC isolated from brain tumors compared to normal brain EC109. Furthermore, growth factor-induced miR-296 contribution to angiogenesis is mediated by targeting hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGS) and thereby reducing HGS-mediated degradation of VEGFR2 and PDGFRβ109.

The identification of miRNAs as regulators of both EC-mediated angiogenesis, tumor-induced angiogenesis and survival is relevant for the therapy of cancer suggesting that antagonism of these key miRNAs may be an attractive strategy.

miRNAs as potential therapeutics targets for angiogenesis

miRNAs are important players and regulators of both angiogenic processes and responses, thus making them promising targets for potential therapeutics. The fact that miRNAs bind to their target mRNAs by Watson-Crick base pairing, indicates that the usage of an oligonucleotide complementary to the miRNA that effectively competes with the mRNA target, i.e. “antimiRs”, represents an obvious and potential effective way of inactivating pathological miRNAs and thus avoiding down regulation of important targets that promote the stimulation of gene expression129-131. Alternatively, miRNA mimics - double stranded oligonucleotides designed to simulate the function of endogenous mature miRNAs- may induce target down regulation and thereby diminish gene expression, however this approach has not been tested in vivo132,133.

The use of antimiRs in cultured cells have been successful, however, the key development was chemical modification of miRNA inhibitors for in vivo utility. The large body of research discovered during the development of antisense therapeutics have led to effective strategies for the pharmacological delivery of nucleic acids, facilitating the development of small interfering (si)RNA therapeutics134, and now, also miRNA therapeutics135. Three different chemical modifications have been carried out to fulfill the inhibition of miRNA function in vivo. One class of antimiRs is conjugated to cholesterol (antagomiR) to facilitate cellular uptake. Other classes use oligonucleotides with with locked nucleotides acid (LNA-antimiRs) or the 2′-O-methoxyethyl phosphorothioate (2′-MOE) modification. Antagonism of miR-122 in mouse liver using these three classes of antimiRs in three independent studies found that miR-122 antagonism led to reduced plasma cholesterol levels129-131.

An important caveat to these new therapeutics approaches is the cell-tissue specificity. Furthermore, the regulatory actions mediated by miRNAs are complex since they can act both as positive or negative modulators, bind to hundreds of different targets, while each target may be regulated by several miRNAs. Indeed, the same miRNA can cause the opposite biological effect depending on the context, as exemplified by miR-221/221, (i.e. targeting important regulators of proangiogenic endothelial cell function (c-kit, eNOS) but also the tumor suppressor p27(Kip1) in cancer cells84. Conversely, miR-17-92 cluster components have been shown to participate in EC-mediated angiogenic functions20 and oncogenic functions as indicated by their upregulation solid tumors such as colorectal cancer, non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC)70. Taken together, antimiRs targeting components of this cluster is a feasible strategy for both antitumor and anti-angiogenic therapy. The relative specificity of miR-126 expression in EC and its requirement for vascular integrity and angiogenesis17,22, also suggests it may be a potential target for efficient antimiR therapy in situations of pathological vascularization, such as retinopathy and cancer. However, overexpression of miR-126 must be carefully considered as there is no direct evidence regarding introduction of miR-126 in non-endothelial cells. This underscores the critical importance of cell/tissue-specific miRNA targeting. Therefore, both the inhibition and the mimicry of a miRNA in tissues other than diseased tissue must be considered. In regards miRNA therapeutics, there are many efforts to develop a more practical and specific strategy suitable for human therapy. A promising approach for siRNA, is to use targeting antibodies that undergo internalization after binding to cell specific surface receptors. To carry siRNA, antibodies can be decorated on liposomes pre-packaged with siRNA or fused to positively charged proteins or peptides that bind nucleic acids via electrostatic interactions136-139. Since miRNA mimics constructs are analogous to siRNA molecules, similar strategies could apply for miRNA mimic cell targeting.

Concluding remarks

miRNAs are a relatively recent discovery that emerged as important regulators of gene expression, and it appears that miRNAs are implicated in most, if not all, cellular processes and many human diseases. In the present review we have summarized the role of miRNAs in the regulation of angiogenesis and examined their potential applicability for the treatment of diseases associated with aberrant pathological angiogenesis (cancer or macular degeneration) or defective angiogenesis (myocardial ischemia or peripheral vascular disease). miRNAs constitute a fundamental regulatory network for fine-tune regulation of gene expression and therefore the maintenance of cellular functions necessary for an adequate angiogenic response. The extensive number of miRNAs and the unprecedented complexity guarantee the discovery of new and unanticipated roles of miRNAs in the control of angiogenesis. Genomics efforts, such as massive parallel miRNA and mRNA expression profiling in angiogenic-associated diseases in combination with loss- or gain-of-functions screens in EC, in combination with adequate target validation and large-scale proteomics are feasible approaches to help understand the complex miRNA-mediated gene regulatory networks in angiogenesis.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported in part by grant from the National Institute of Health (R01 HL64793, RO1 HL 61371, R01 HL 57665, PO1 HL 70295, Contract No. N01-HV-28186 (NHLBI-Yale Proteomics Contract) to W.C.S., and by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association to Y.S.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K, Rossant J. Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature. 2005;438:937–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med. 2003;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romagnani P, Lasagni L, Annunziato F, Serio M, Romagnani S. CXC chemokines: the regulatory link between inflammation and angiogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleaver O, Melton DA. Endothelial signaling during development. Nat Med. 2003;9:661–668. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang TC, Mendell JT. microRNAs in vertebrate physiology and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:215–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNAs in neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNAs: powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2369–2376. doi: 10.1172/JCI33099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh RF, Wythe JD, Ivey KN, Bruneau BG, Stainier DY, Srivastava D. miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell. 2008;15:272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, Mercatanti A, Hammond S, Rainaldi G. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108:3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:1164–1173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265065.26744.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, Gerber SA, Harrison KD, Pober JS, Iruela-Arispe ML, Merkenschlager M, Sessa WC. Dicer-dependent endothelial microRNAs are necessary for postnatal angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804597105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbich C, Kuehbacher A, Dimmeler S. Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:581–588. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X, McAnally J, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berezikov E, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. Approaches to microRNA discovery. Nat Genet. 2006;38(Suppl):S2–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krutzfeldt J, Stoffel M. MicroRNAs: a new class of regulatory genes affecting metabolism. Cell Metab. 2006;4:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Embo J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruby JG, Jan CH, Bartel DP. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature. 2007;448:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature05983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maniataki E, Mourelatos Z. A human, ATP-independent, RISC assembly machine fueled by pre-miRNA. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2979–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters L, Meister G. Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol Cell. 2007;26:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamura K, Phillips MD, Tyler DM, Duan H, Chou YT, Lai EC. The regulatory activity of microRNA* species has substantial influence on microRNA and 3′ UTR evolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:354–363. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Filipowicz W. Repression of protein synthesis by miRNAs: how many mechanisms? Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J. Control of protein synthesis and mRNA degradation by microRNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rana TM. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wienholds E, Koudijs MJ, van Eeden FJ, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. The microRNA-producing enzyme Dicer1 is essential for zebrafish development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:217–218. doi: 10.1038/ng1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang WJ, Yang DD, Na S, Sandusky GE, Zhang Q, Zhao G. Dicer is required for embryonic angiogenesis during mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9330–9335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris KS, Zhang Z, McManus MT, Harfe BD, Sun X. Dicer function is essential for lung epithelium morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510839103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yi R, O'Carroll D, Pasolli HA, Zhang Z, Dietrich FS, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Morphogenesis in skin is governed by discrete sets of differentially expressed microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andl T, Murchison EP, Liu F, Zhang Y, Yunta-Gonzalez M, Tobias JW, Andl CD, Seykora JT, Hannon GJ, Millar SE. The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cobb BS, Nesterova TB, Thompson E, Hertweck A, O'Connor E, Godwin J, Wilson CB, Brockdorff N, Fisher AG, Smale ST, Merkenschlager M. T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1367–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liston A, Lu LF, O'Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1993–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cobb BS, Hertweck A, Smith J, O'Connor E, Graf D, Cook T, Smale ST, Sakaguchi S, Livesey FJ, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. A role for Dicer in immune regulation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2519–2527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, Vanti WB, Voronov SV, Murchison E, Hannon G, Abeliovich A. A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2007;317:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Rourke JR, Georges SA, Seay HR, Tapscott SJ, McManus MT, Goldhamer DJ, Swanson MS, Harfe BD. Essential role for Dicer during skeletal muscle development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobayashi T, Lu J, Cobb BS, Rodda SJ, McMahon AP, Schipani E, Merkenschlager M, Kronenberg HM. Dicer-dependent pathways regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1949–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hayashi K, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Kaneda M, Tang F, Hajkova P, Lao K, O'Carroll D, Das PP, Tarakhovsky A, Miska EA, Surani MA. MicroRNA biogenesis is required for mouse primordial germ cell development and spermatogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou X, Jeker LT, Fife BT, Zhu S, Anderson MS, McManus MT, Bluestone JA. Selective miRNA disruption in T reg cells leads to uncontrolled autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1983–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koralov SB, Muljo SA, Galler GR, Krek A, Chakraborty T, Kanellopoulou C, Jensen K, Cobb BS, Merkenschlager M, Rajewsky N, Rajewsky K. Dicer ablation affects antibody diversity and cell survival in the B lymphocyte lineage. Cell. 2008;132:860–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen JF, Murchison EP, Tang R, Callis TE, Tatsuguchi M, Deng Z, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Schneider MD, Selzman CH, Meissner G, Patterson C, Hannon GJ, Wang DZ. Targeted deletion of Dicer in the heart leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710228105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.da Costa Martins PA, Bourajjaj M, Gladka M, Kortland M, van Oort RJ, Pinto YM, Molkentin JD, De Windt LJ. Conditional dicer gene deletion in the postnatal myocardium provokes spontaneous cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2008;118:1567–1576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shilo S, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK. Evidence for the involvement of miRNA in redox regulated angiogenic response of human microvascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:471–477. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Otsuka M, Jing Q, Georgel P, New L, Chen J, Mols J, Kang YJ, Jiang Z, Du X, Cook R, Das SC, Pattnaik AK, Beutler B, Han J. Hypersusceptibility to vesicular stomatitis virus infection in Dicer1-deficient mice is due to impaired miR24 and miR93 expression. Immunity. 2007;27:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otsuka M, Zheng M, Hayashi M, Lee JD, Yoshino O, Lin S, Han J. Impaired microRNA processing causes corpus luteum insufficiency and infertility in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1944–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI33680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiemer EA. The role of microRNAs in cancer: no small matter. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1529–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shilo S, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK. MicroRNA in cutaneous wound healing: a new paradigm. DNA Cell Biol. 2007;26:227–237. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Asai T, Suzuki Y, Matsushita S, Yonezawa S, Yokota J, Katanasaka Y, Ishida T, Dewa T, Kiwada H, Nango M, Oku N. Disappearance of the angiogenic potential of endothelial cells caused by Argonaute2 knockdown. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1655–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.1210204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pillai RS, Artus CG, Filipowicz W. Tethering of human Ago proteins to mRNA mimics the miRNA-mediated repression of protein synthesis. Rna. 2004;10:1518–1525. doi: 10.1261/rna.7131604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fukagawa T, Nogami M, Yoshikawa M, Ikeno M, Okazaki T, Takami Y, Nakayama T, Oshimura M. Dicer is essential for formation of the heterochromatin structure in vertebrate cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:784–791. doi: 10.1038/ncb1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, Olson EN. Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007;316:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.1139089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsui J, Wakabayashi T, Asada M, Yoshimatsu K, Okada M. Stem cell factor/c-kit signaling promotes the survival, migration, and capillary tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18600–18607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, Valtieri M, Calin GA, Liu CG, Sorrentino A, Croce CM, Peschle C. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18081–18086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506216102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sata M. Role of circulating vascular progenitors in angiogenesis, vascular healing, and pulmonary hypertension: lessons from animal models. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1008–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000206123.94140.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Papapetropoulos A, Garcia-Cardena G, Madri JA, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3131–3139. doi: 10.1172/JCI119868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.le Sage C, Nagel R, Egan DA, Schrier M, Mesman E, Mangiola A, Anile C, Maira G, Mercatelli N, Ciafre SA, Farace MG, Agami R. Regulation of the p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. Embo J. 2007;26:3699–3708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Berezikov E, de Bruijn E, Horvitz HR, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science. 2005;309:310–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campagnolo L, Leahy A, Chitnis S, Koschnick S, Fitch MJ, Fallon JT, Loskutoff D, Taubman MB, Stuhlmann H. EGFL7 is a chemoattractant for endothelial cells and is up-regulated in angiogenesis and arterial injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:275–284. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62972-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Soncin F, Mattot V, Lionneton F, Spruyt N, Lepretre F, Begue A, Stehelin D. VE-statin, an endothelial repressor of smooth muscle cell migration. Embo J. 2003;22:5700–5711. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fitch MJ, Campagnolo L, Kuhnert F, Stuhlmann H. Egfl7, a novel epidermal growth factor-domain gene expressed in endothelial cells. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:316–324. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parker LH, Schmidt M, Jin SW, Gray AM, Beis D, Pham T, Frantz G, Palmieri S, Hillan K, Stainier DY, De Sauvage FJ, Ye W. The endothelial-cell-derived secreted factor Egfl7 regulates vascular tube formation. Nature. 2004;428:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature02416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stoll M, Steckelings UM, Paul M, Bottari SP, Metzger R, Unger T. The angiotensin AT2-receptor mediates inhibition of cell proliferation in coronary endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:651–657. doi: 10.1172/JCI117710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Munzenmaier DH, Greene AS. Opposing actions of angiotensin II on microvascular growth and arterial blood pressure. Hypertension. 1996;27:760–765. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Silvestre JS, Tamarat R, Senbonmatsu T, Icchiki T, Ebrahimian T, Iglarz M, Besnard S, Duriez M, Inagami T, Levy BI. Antiangiogenic effect of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in mice hindlimb. Circ Res. 2002;90:1072–1079. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019892.41157.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Martin MM, Buckenberger JA, Jiang J, Malana GE, Nuovo GJ, Chotani M, Feldman DS, Schmittgen TD, Elton TS. The human angiotensin II type 1 receptor +1166 A/C polymorphism attenuates microrna-155 binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24262–24269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 96.Otani A, Takagi H, Suzuma K, Honda Y. Angiotensin II potentiates vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenic activity in retinal microcapillary endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1998;82:619–628. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, Nervi C, Bozzoni I. A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell. 2005;123:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:719–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kulshreshtha R, Davuluri RV, Calin GA, Ivan M. A microRNA component of the hypoxic response. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:667–671. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pawlicki JM, Steitz JA. Primary microRNA transcript retention at sites of transcription leads to enhanced microRNA production. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:61–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature. 2007;449:919–922. doi: 10.1038/nature06205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Lagna G, Hata A. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature. 2008;454:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature07086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen Y, Gorski DH. Regulation of angiogenesis through a microRNA (miR-130a) that down-regulates antiangiogenic homeobox genes GAX and HOXA5. Blood. 2008;111:1217–1226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fasanaro P, D'Alessandra Y, Di Stefano V, Melchionna R, Romani S, Pompilio G, Capogrossi MC, Martelli F. MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15878–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wurdinger T, Tannous BA, Saydam O, Skog J, Grau S, Soutschek J, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Krichevsky AM. miR-296 regulates growth factor receptor overexpression in angiogenic endothelial cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hebert C, Norris K, Scheper MA, Nikitakis N, Sauk JJ. High mobility group A2 is a target for miRNA-98 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hua Z, Lv Q, Ye W, Wong CK, Cai G, Gu D, Ji Y, Zhao C, Wang J, Yang BB, Zhang Y. MiRNA-directed regulation of VEGF and other angiogenic factors under hypoxia. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e116. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Garzon R, Alder H, Agosto-Perez FJ, Davuluri R, Liu CG, Croce CM, Negrini M, Calin GA, Ivan M. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1859–1867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. Rna. 2004;10:1957–1966. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhou X, Ruan J, Wang G, Zhang W. Characterization and identification of microRNA core promoters in four model species. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]